Revered by some as a freedom fighter and reviled by others as a fanatic, John Brown is one of the most polarizing figures in American history. Long before his famous 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry, Brown experienced a formative moment in his youth that would ignite an unyielding hatred of slavery and a personal vow to destroy it, even if it meant using force.

A Childhood Shaped By Moral Conviction

Born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, John Brown was raised in a deeply religious and abolitionist household. His father, Owen Brown, was a devout Calvinist who believed slavery was a sin against both God and humanity. The Browns moved to Ohio, a free state, where young John grew up with a strong sense of moral righteousness and personal responsibility—principles that would later drive his uncompromising stance on slavery.

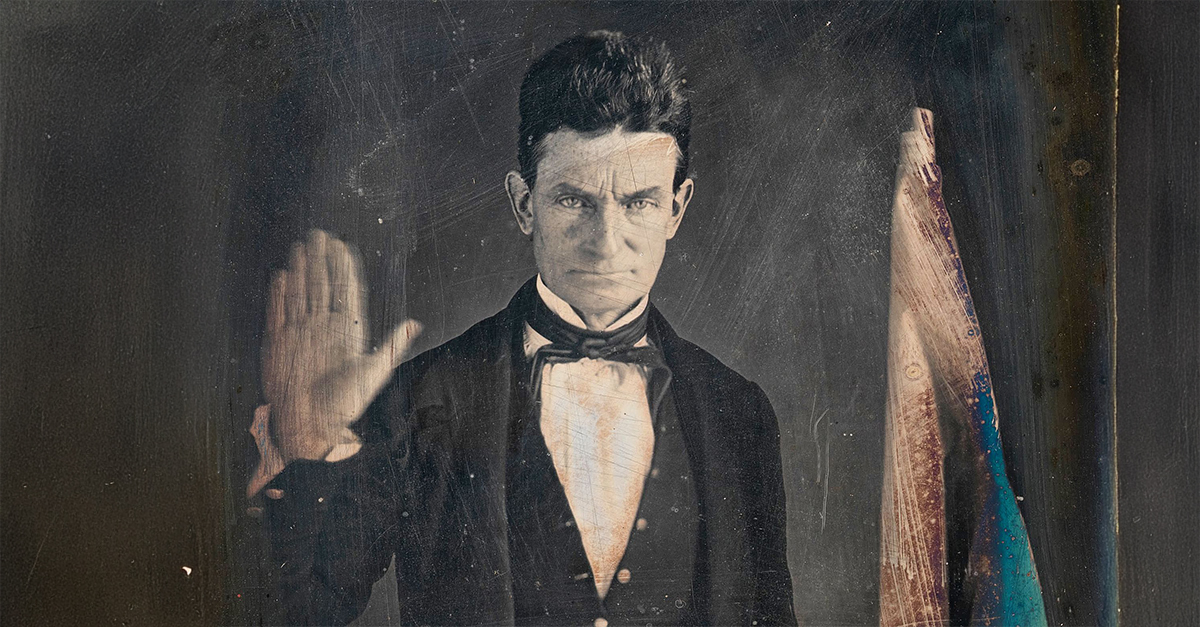

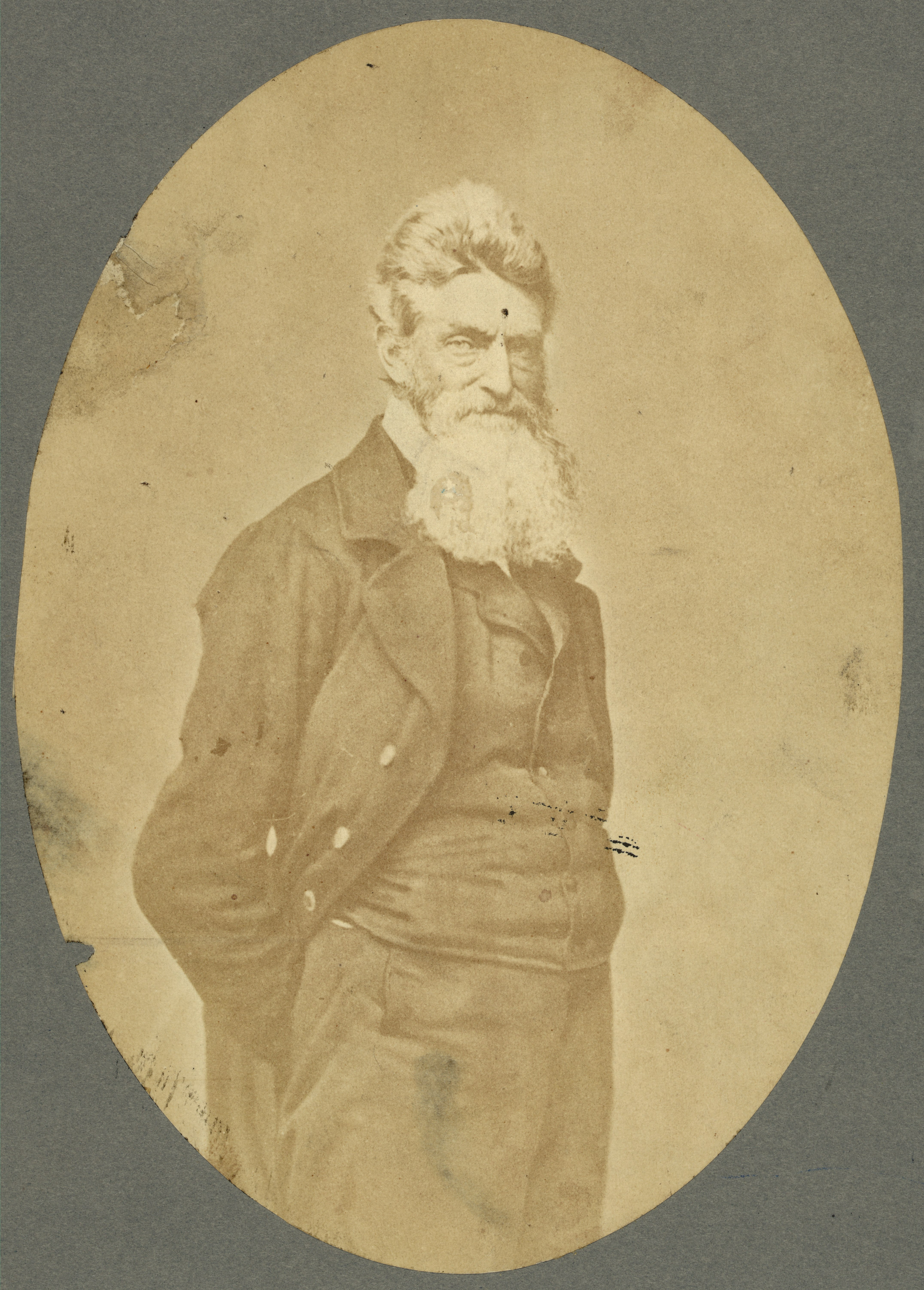

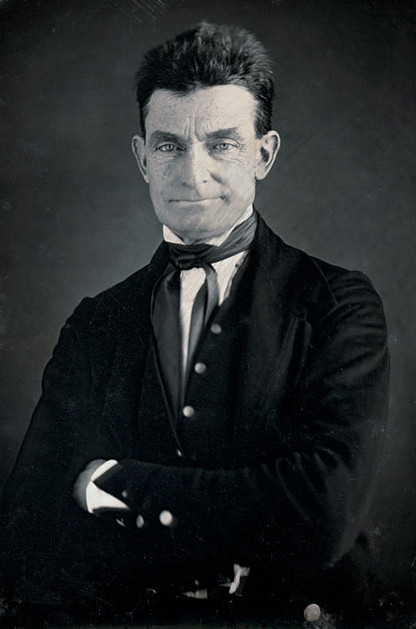

Augustus Washington, Wikimedia Commons

Augustus Washington, Wikimedia Commons

The Moment Of Trauma In Hudson, Ohio

The defining moment that pushed John Brown from moral opposition to militant resistance came when he was a boy living in Hudson, Ohio. Around the age of 12, Brown witnessed a Black boy—roughly his own age—being beaten and abused by a white man. The boy, who was enslaved, had been brought to Ohio by a Southern family despite Ohio’s free-state status. The cruelty was open and unprovoked.

The Impact Of Witnessing Brutality

This episode seared itself into Brown’s memory. He later described it as the moment that “made him a determined enemy of slavery.” The young Brown was stunned by the contrast between the Christian values he was taught and the inhuman treatment he saw with his own eyes. He began to question how a supposedly moral nation could allow such horror to go on.

A Personal Vow Of Resistance

After this traumatic experience, Brown claimed to have made a personal vow before God to dedicate his life to the destruction of slavery. While many abolitionists of the era favored political and religious persuasion, Brown believed these approaches were too slow and ineffective. At a young age he sensed that only direct, even violent, action could eradicate such an entrenched evil.

Isolation And Intensifying Beliefs

Brown’s moral intensity often isolated him from others. He married and raised a family, but found few allies who shared his increasingly radical views. He joined various anti-slavery societies and helped slaves escape via the Underground Railroad, but he was frustrated with the pacifism and caution of mainstream abolitionists. His belief in righteous violence grew more pronounced.

The Influence Of Calvinist Theology

Brown’s interpretation of Calvinism also shaped his militant views. He saw himself as an instrument of divine justice, much like the biblical figures who were called to carry out God’s wrath. For Brown, ending slavery wasn’t just a political or social goal—it was a sacred mission. The incident in Hudson had given that mission its personal and emotional foundation.

Confronting The Limits Of Law

Living in free states did little to reassure Brown that the law would abolish slavery. Events like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required the return of escaped slaves even from free states, convinced him that American legal institutions were complicit in maintaining slavery. Brown saw himself as operating outside a legal system that was rotten to the core, answering instead to a higher moral authority.

The Road To Violence

By the 1850s, Brown had transformed from a committed abolitionist into a revolutionary. He participated in violent clashes in Kansas during the “Bleeding Kansas” conflict, where he led attacks on pro-slavery settlers. His radicalization was complete, driven by a combination of early trauma, unshakable belief in divine justice, and the failures of peaceful abolitionism.

A Life Cast In Outrage

John Brown’s journey toward militant abolitionism began with the trauma of witnessing a young boy’s brutal treatment in what was supposed to be a free state. That image haunted him and became the moral flashpoint for a life dedicated to ending slavery at any cost. His methods would divide a nation already on the path to civil war, but his conviction was forged in a moment that revealed the cruelty of slavery in its rawest form.

You May Also Like:

43 Unsettling Facts About the Antebellum South

Honorable Facts About Abraham Lincoln, America’s Most Tragic President