A Media Magnate—And A Monster?

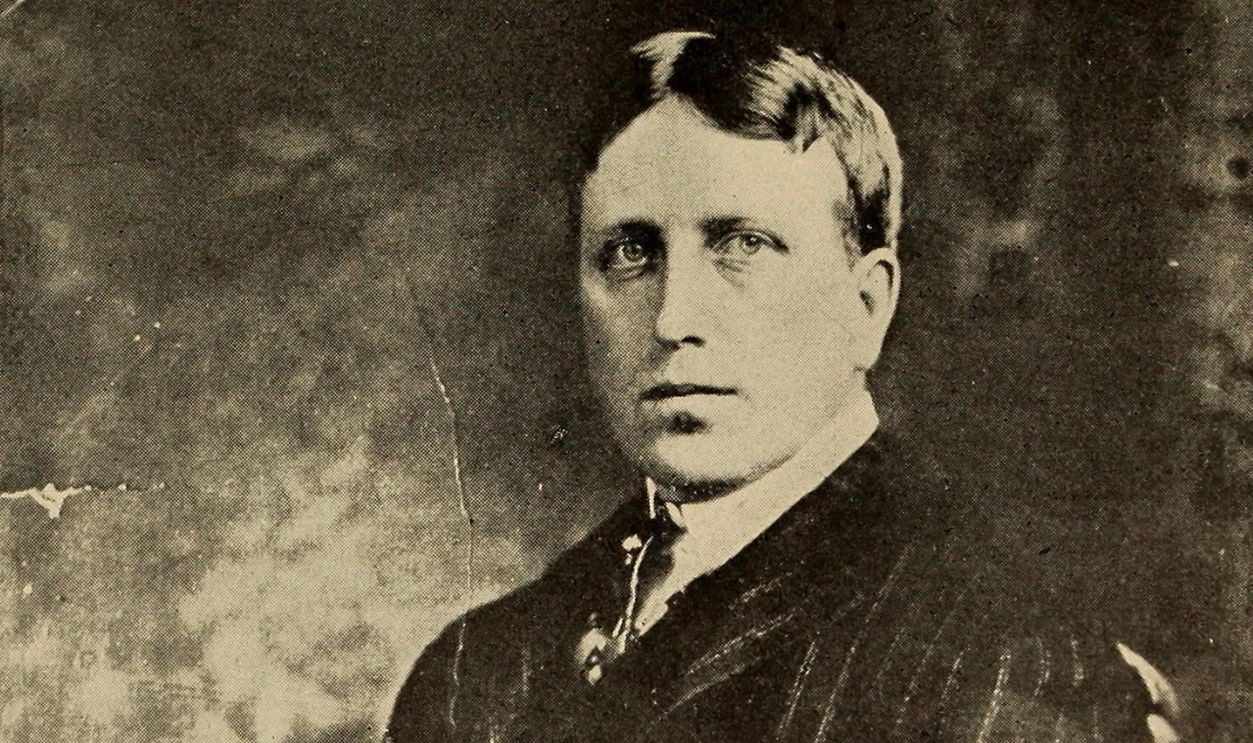

William Randolph Hearst wasn’t just the scion of the Hearst dynasty—he was a king-making media magnate. But his penchant for sensational “yellow” journalism, rivalries with competing newspapers, and scandalous affairs nearly depleted the family fortune.

In fact, he was such a controversial figure that he inspired one of film’s most memorable villains.

1. He Was Minted

William Randolph Hearst was minted from the time he was born—almost literally. Born in April 1863, he was the son of the millionaire mining magnate and patriarch of the Hearst dynasty, George Hearst, and his wife, Phoebe Apperson. Unlike his father, however, the younger Hearst was only mining trouble.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

2. He Was Expelled From Harvard

Thanks to his father’s money, Hearst only attended the best schools. First, he was a student at St Paul’s School, a preparatory school in New Hampshire. Following that, he went off to Harvard where he joined a fraternity and various prestigious clubs. But he wasn’t there for long.

Before he could graduate, Harvard had him expelled. It’s not hard to understand why.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

3. He Was A Poopy Prankster

It seems that, while attending Harvard, Hearst did just about everything other than studying. He developed a reputation on campus as a partier and crude prankster. Some of his more notable “accomplishments” included throwing parties on Harvard Square and sending pudding pots filled with excrement to his professors.

Pretty soon, he would be printing the headlines, not making them.

B. M. Clinedinst, Wikimedia Commons

B. M. Clinedinst, Wikimedia Commons

4. He Took Over His Father’s Newspaper

Even if he didn’t have a fancy Harvard degree, Hearst had something that even fewer people had: a rich dad. Following his expulsion from Harvard, Hearst stepped in to manage his father’s newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner.

The elder Hearst had “won” the paper seven years prior in 1880 as a form of repayment for gambling debts. Gambling is exactly what the younger Hearst did with the paper.

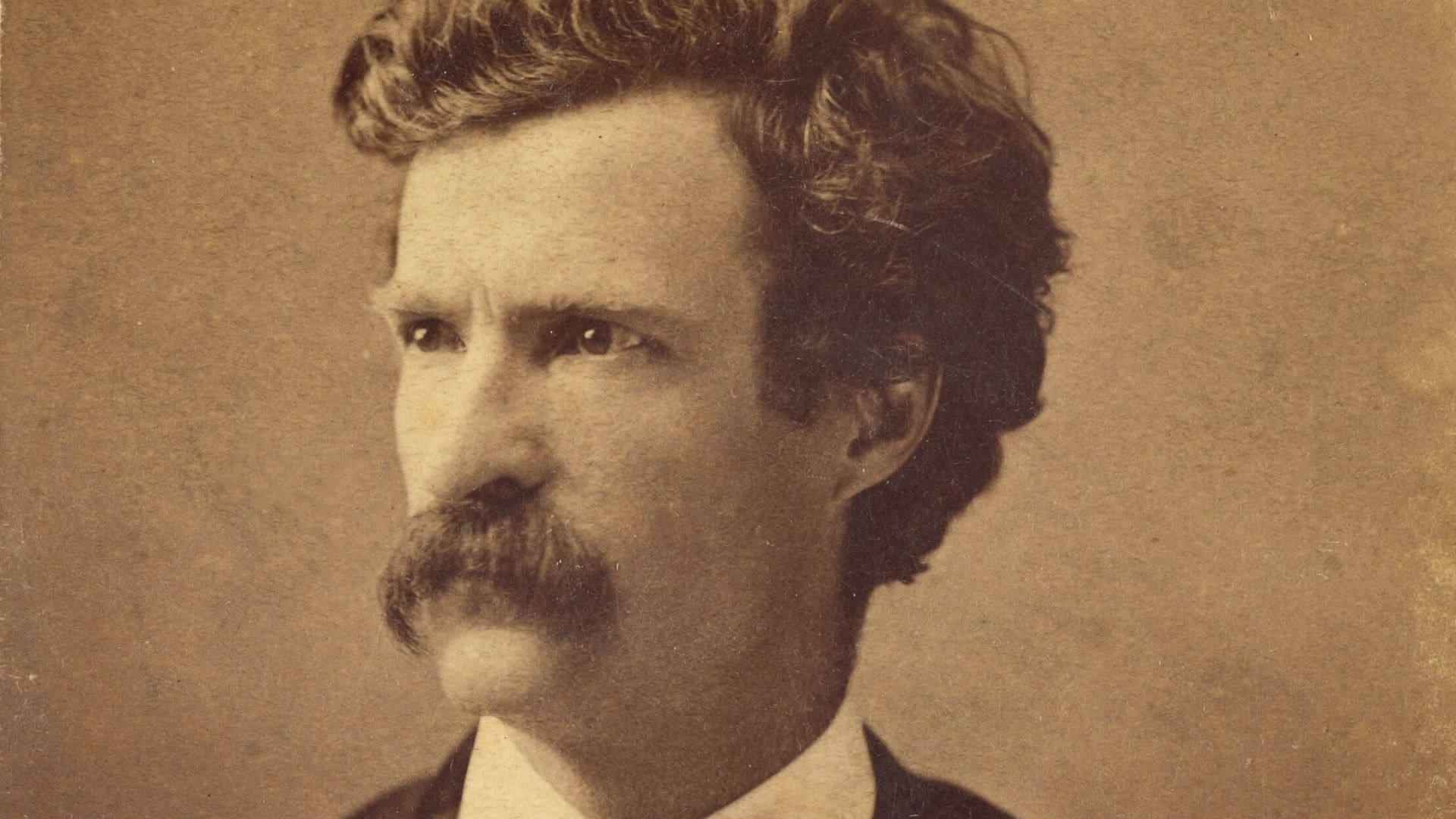

5. He Hired Mark Twain

Hearst might not have excelled at Harvard, but that didn’t mean he wasn’t sharp as a tack. He knew that the secret to any newspaper’s success was its writing—so he hired the best writers. Hearst brought on acclaimed literary heavyweights Mark Twain and Jack London amongst others along with famed political cartoonist Homer Davenport.

With a new staff on hand, Hearst rebranded his father’s newspaper, giving it the motto “Monarch of the Dailies”. Superstar staff or not, he was definitely not shy about sharing his opinions in his papers.

Jeremiah Gurney&Son, Wikimedia Commons

Jeremiah Gurney&Son, Wikimedia Commons

6. He Was An Equal Opportunist Journalist

Hearst broke with tradition and openly aired his populist views in his newspaper. He routinely exposed corruption in local government and even took aim at his own class of wealthy business people. In fact, not even his own family was safe from his scathing articles as he regularly attacked companies in which his family had invested.

His bluntness clearly paid off; before long, Hearst was the only name in the San Francisco news game. But he wanted so much more.

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

7. He Set His Sights Beyond The Bay

Even in the early days of running the Examiner, Hearst had set his sights far beyond the Bay Area. He knew that to create a nationwide news empire, he had to conquer one city: New York. That singular ambition shaped everything that followed—including some of his most ruthless business decisions.

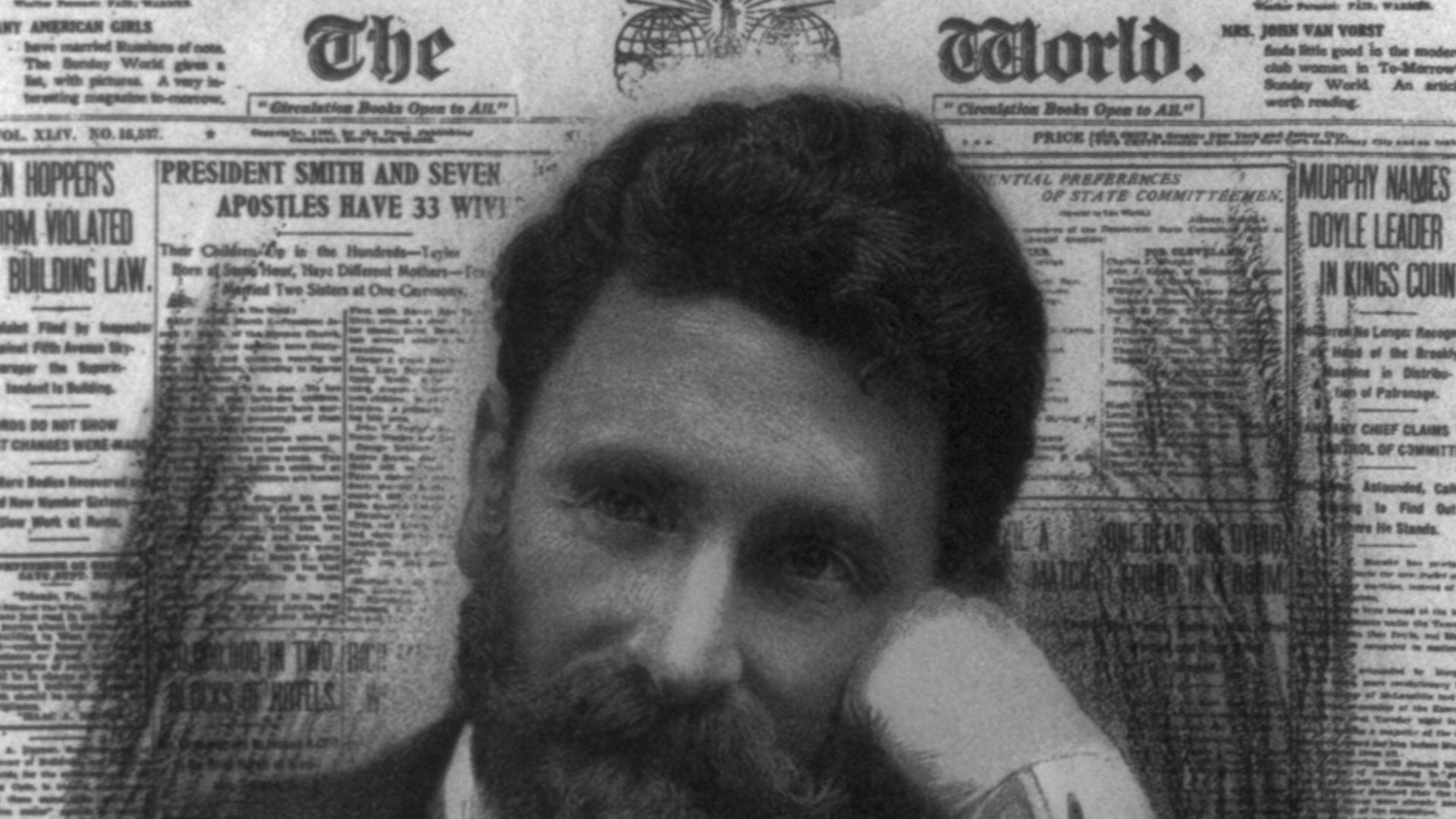

8. He Picked Pulitzer’s Best

With his mother’s financial backing, Hearst bought the floundering New York Morning Journal in 1895—and then proceeded to shake everything up. He poached the top talent from his competitors in the Big Apple faster than ink dries on gazette paper. But he singled in on one paper in particular: Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World.

What ensued was a knock-down-drag-out journalism battle like the world had never seen before.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

9. He Was A Magnanimous Media Magnate

To attract the best talent and run his competitors out of business, Hearst made himself into a magnanimous media magnate. According to the historian Kenneth Whyte, Hearst was “unfailingly polite” and indulged “prima donnas, eccentrics, bohemians, drinkers, or reprobates”...as long as they could write. Of course, it didn’t hurt that he paid better than anyone else.

In fact, working for Hearst barely required any work at all.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

10. He Threw Wild Work Parties

Working at a Hearst-owned newspaper was a good time. He brought together a legendary staff—including Ambrose Bierce and Mark Twain—and then kept them entertained with parties, impromptu “dancing jigs,” and outlandish office antics. One gossip even claimed the newsroom soirées featured “abandoned dancing girls”.

But when it came time for business, Hearst was not messing around.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

11. He Put Words Into Action

Hearst didn’t just want to write the news—he wanted to be the news. Adopting the motto “While others Talk, the Journal Acts” he pioneered a brand of crusading journalism that often bled into activism. If there was injustice, scandal, or corruption afoot, Hearst wasn’t above sensationalizing it—and profiting off the outrage.

This brash new brand of journalism was just the beginning.

Hearst publishing, Wikimedia Commons

Hearst publishing, Wikimedia Commons

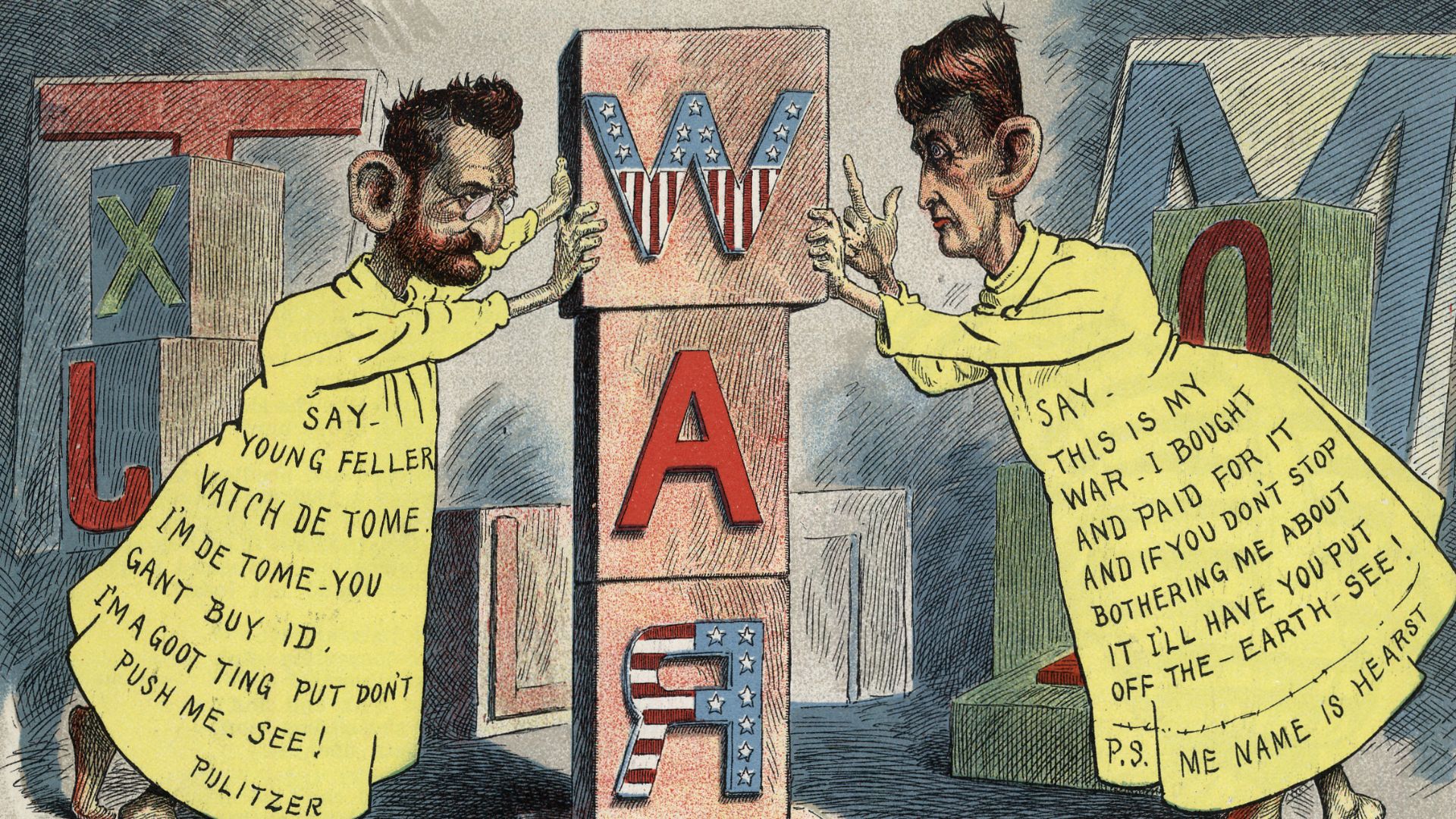

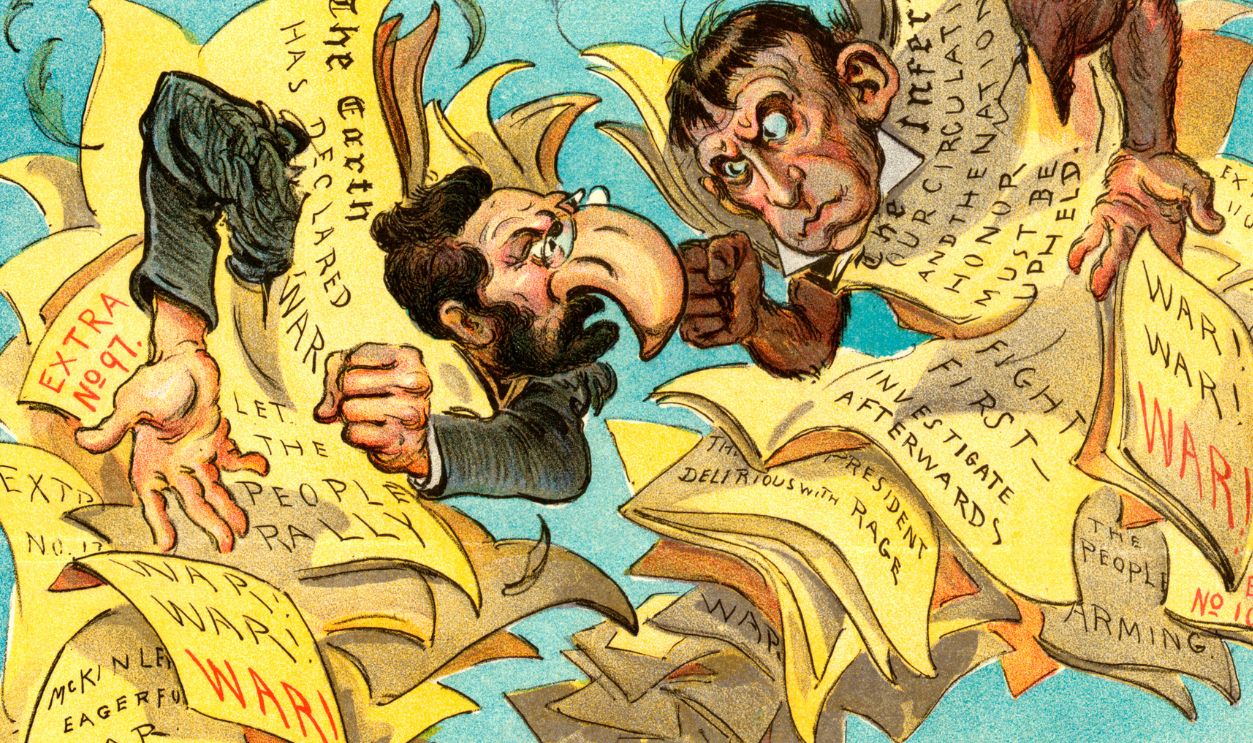

12. He Perfected “Yellow” Journalism

Hearst and his rival Joseph Pulitzer waged an all-out tabloid feud. But instead of destroying the news business, they created a whole new genre of journalism. Both papers—Hearst’s Journal and Pulitzer’s World—pushed lurid headlines, high-impact stories, controversial cartoons, and human drama to dizzying extremes.

The press dubbed the style “yellow journalism” after Richard Outcault’s “Yellow Boy” comics. But the profits were no laughing matter.

Leon Barritt, Wikimedia Commons

Leon Barritt, Wikimedia Commons

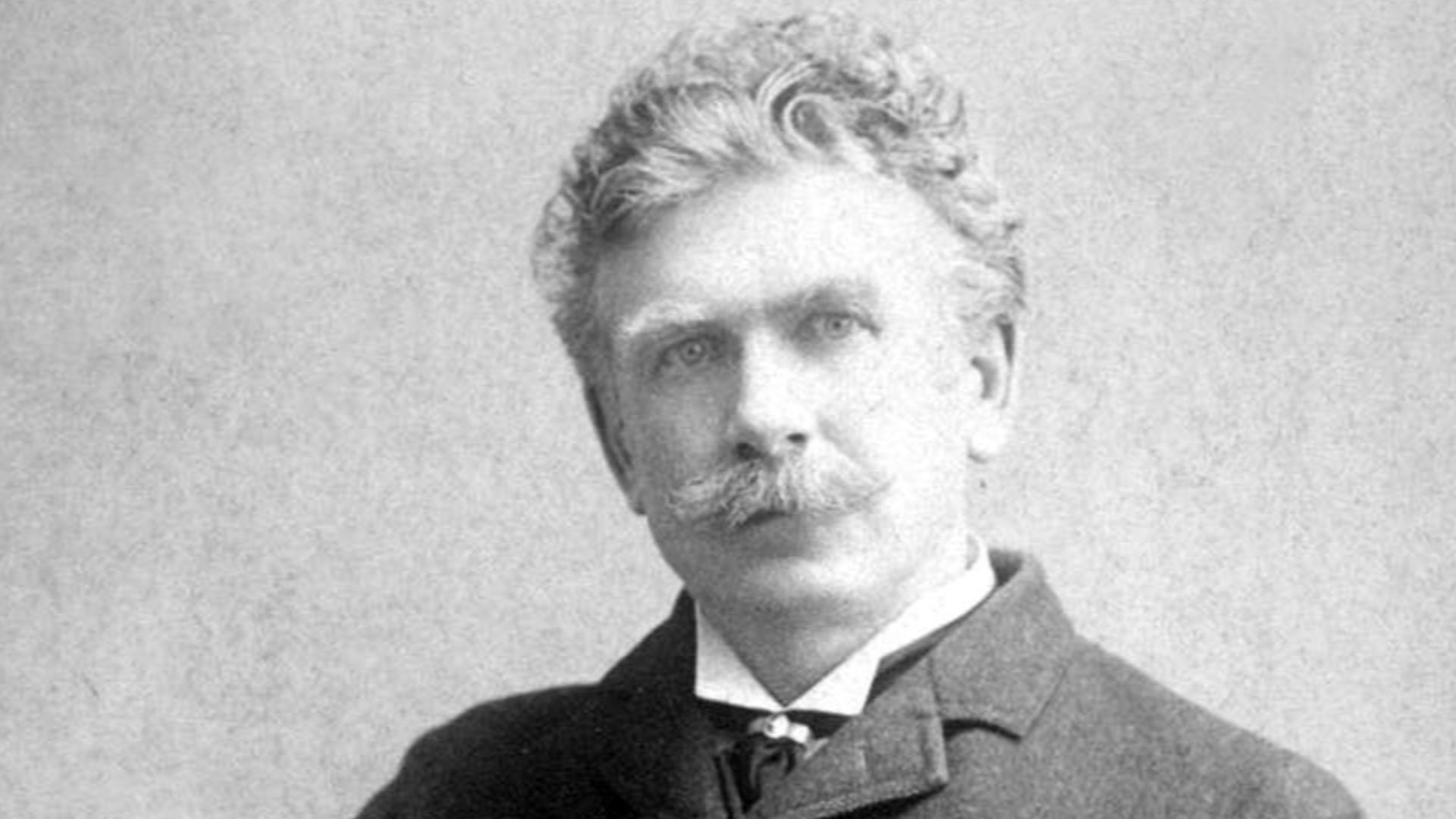

13. He Wasn’t As Trashy As They Said

Critics blasted Hearst for turning the news into a circus—but they might not have given him enough credit. Historian Kenneth Whyte claimed that, despite the spectacle, the Journal was “demanding” of its reporters and “sophisticated by contemporary standards”.

In short: Hearst’s papers may have screamed, but they still made sense. Even if the money never did.

14. He Burned Money Like Paper

After his father’s passing, Hearst inherited a considerable fortune, but no amount of money could keep up with his spending habits. When someone warned his mother that he was torching a million dollars a year, Phoebe Hearst reportedly replied, “Too bad. Then he’ll only last 30 years”.

Fortunately for Hearst—and unfortunately for his rivals—he really did have money to burn.

15. He Finally Called A Truce

By 1898, Hearst’s battle with Pulitzer had become a black hole for cash. Both men poured millions into covering the Spanish–American War—and neither saw a return. When the dust settled and the actual cannons stopped firing, Hearst and Pulitzer begrudgingly called a truce.

Only then did Hearst’s Journal finally start turning a profit. He clearly got the better end of the deal.

Education Images, Getty Images

Education Images, Getty Images

16. He Made Headlines With His Headlines

After just one year in the Big Apple, Hearst was already the undisputed king of the New York news business. Following the 1896 election, Heart’s Journal boasted a circulation of over a million, with some issues even topping 1.5 millions copies sold. It was a circulation feat, and one he proudly claimed was “unparalleled in the history of the world”.

He didn’t always use that influence for good.

Hearst publishing, Wikimedia Commons

Hearst publishing, Wikimedia Commons

17. He Started “The Journal’s Fight”

Hearst hadn’t just reported on the Spanish–American War—he helped start it. When the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor, Hearst used the Journal’s considerable readership to whip public outrage into a frenzy. Critics of the paper and of Hearst started calling the conflict “The Journal’s Fight”.

Hearst seemed to lean into his ignominious reputation.

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

18. He (Allegedly) Promised A War

Like he dreamed, Hearst wasn’t just printing the news—he was the news. Legend has it that when Journal illustrator Frederic Remington reported from the field that there was no conflict in Cuba, Hearst replied, “You furnish the pictures and I’ll furnish the war”.

Apocryphal or not, the tale perfectly encapsulated Hearst’s zeal for the conflict.

Davis and Sanford, Wikimedia Commons

Davis and Sanford, Wikimedia Commons

19. He Printed The News From The Battlefield

Not content to cover the Spanish–American Conflict from a distance, Hearst sailed to Cuba with his own team of Journal reporters along with a portable printing press. His willingness to put himself on the frontlines of the stories that his papers covered endeared him to working class readers the world over.

After the fighting ended, the rebels even gifted Hearst a bullet-riddled Cuban flag in thanks for his support.

National Museum of the U.S. Navy, Wikimedia Commons

National Museum of the U.S. Navy, Wikimedia Commons

20. He Expanded To Fuel His Ambitions

Having conquered the news business, Hearst set his sights on politics. But he knew that, if he wanted to win national office, he would need national coverage. So he did what any media magnate would do: he bought more newspapers. Hearst expanded his newspaper holdings to all major cities, from Los Angeles to Boston and back again.

He even started an animation studio to capitalize on the comic strips in his newspapers. Somehow, he was only just getting started.

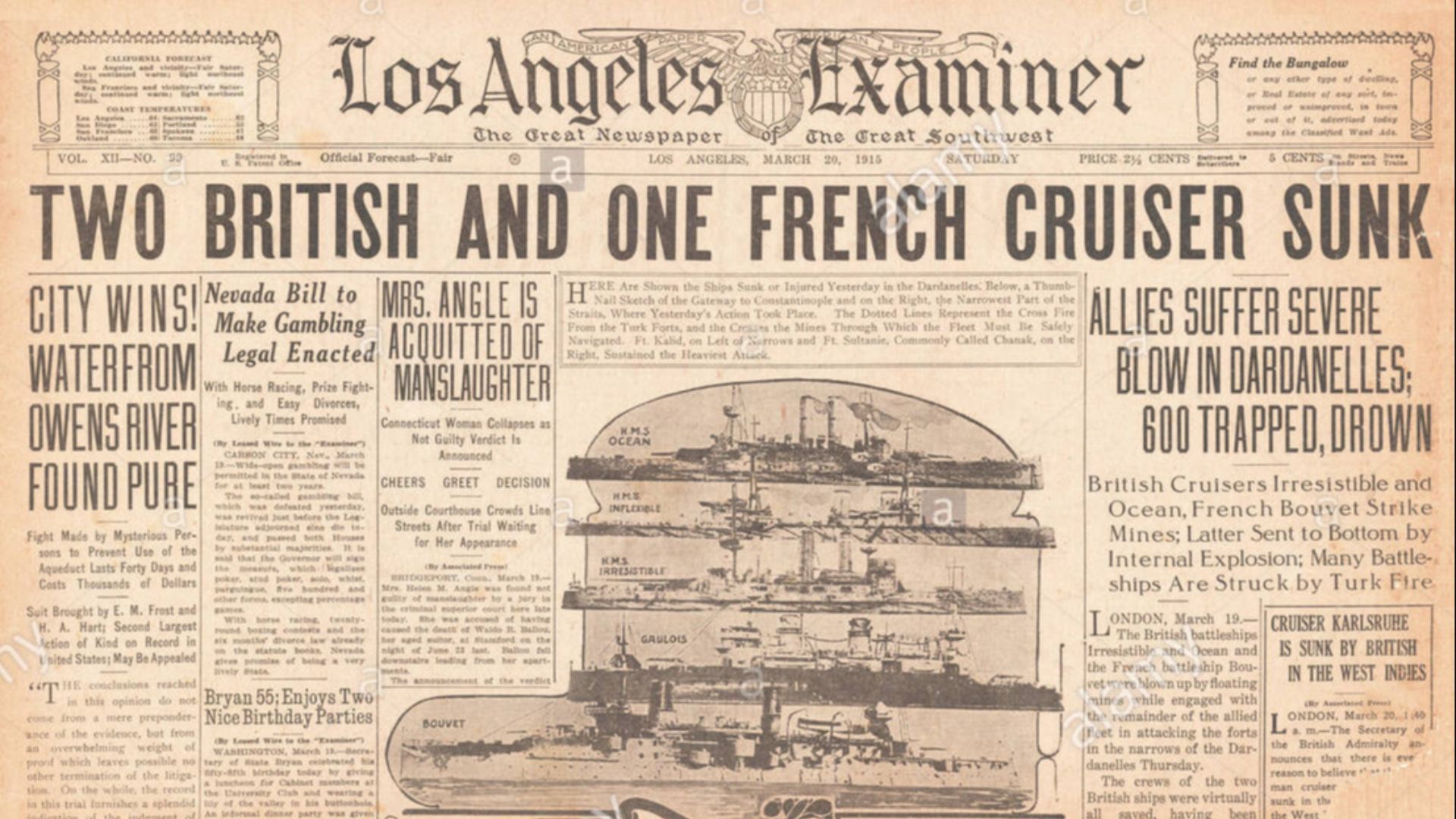

21. He Built A Coast-To-Coast Empire

By the mid-1920s, Hearst’s name wasn’t just on a few mastheads—it was on nearly 30 of them. From the Los Angeles Examiner to the Boston American to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, his empire stretched from sea to shining sea. And it didn’t stop at newspapers. He also controlled a slew of magazines, including Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, and Harper’s Bazaar.

In other words, if you were an American, the news was what Hearst said it was.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

22. He Was A Krazy Kat

The secret to Hearst’s success was also one of the most controversial things about him: he liked an underdog. Hearst unapologetically promoted eccentric writers and cartoonists who would never have found employment at more “respectable” publications. However, his gambles often paid off.

Hearst’s patronage of George Herriman, creator of the surreal comic strip Krazy Kat, is largely responsible for turning the man into a legend. But until now, William Randolph Hearst had experienced nothing but growth and success. That was about to change.

George Herriman, Wikimedia Commons

George Herriman, Wikimedia Commons

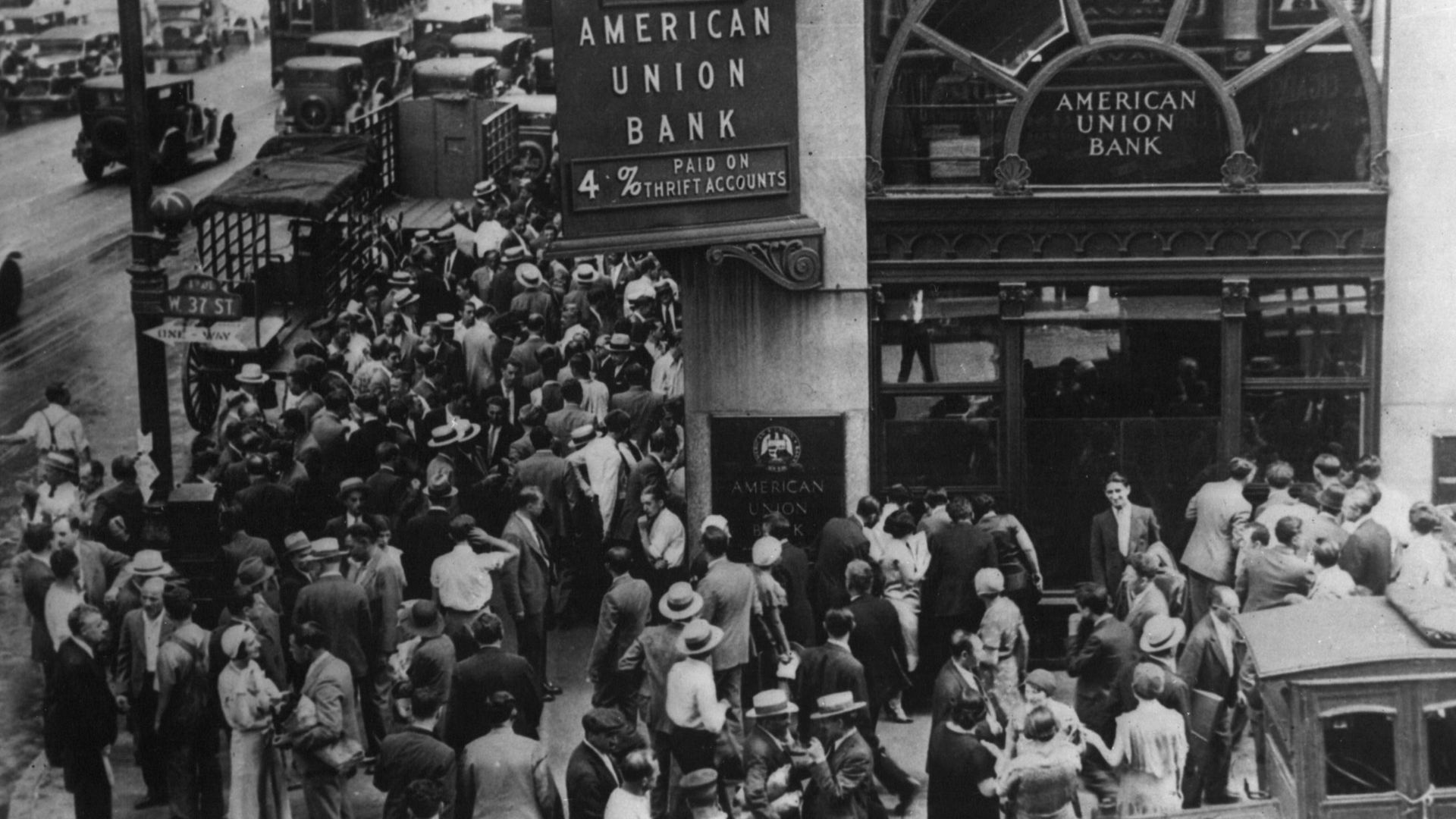

23. He Had A Paper Empire

The roaring 1920s were good to Hearst. His empire reached its peak just before the Great Depression—and then promptly collapsed. In his pursuit to buy up as many papers as possible, Hearst had stretched himself too thin. His newspapers rarely paid for themselves, and when the mining and ranching ventures that he had inherited faltered, so did everything else.

Turns out, his empire actually was made out of paper.

World Telegram staff photographer, Wikimedia Commons

World Telegram staff photographer, Wikimedia Commons

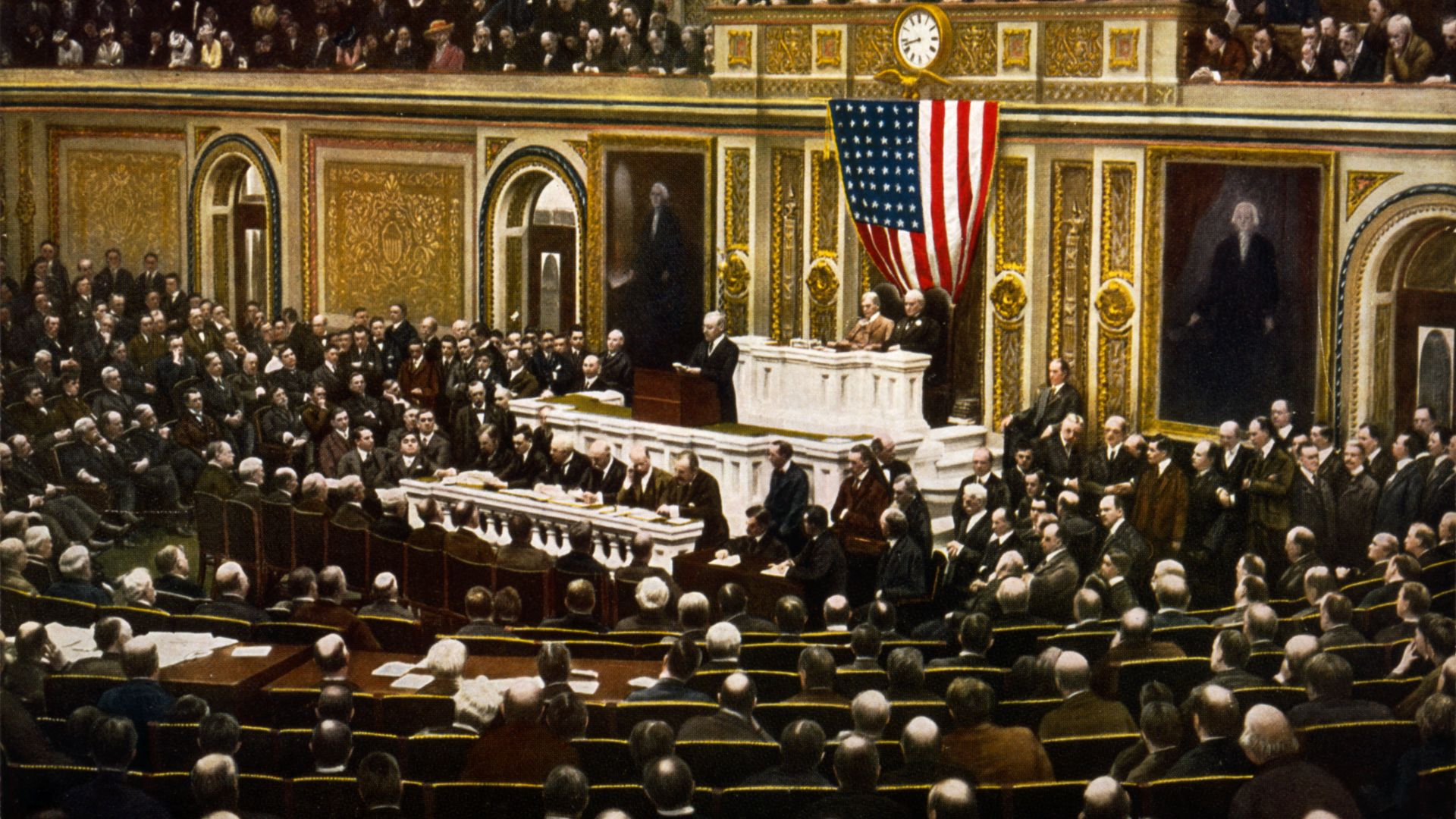

24. He Went From Publisher To Politician

For a brief moment, Hearst swapped headlines for handshakes. With the backing of Tammany Hall—and favorable news coverage from his own publications—Hearst won two terms in Congress, representing New York in the early 1900s. But his ambitions didn’t stop there.

After his Congressional career, Hearst set his sights on even more powerful political office.

25. He Was A Millionaire “Man Of The People”

Hearst might have been the millionaire media magnate son of a millionaire mining magnate, but he claimed to be for the common man. As he attempted to gain political power, Hearst aligned himself with the “left wing” of the Progressive Movement and championed the “working class” who were his newspapers’ primary readers.

But rants against the rich and powerful—as someone who was rich and powerful—fell on deaf ears.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

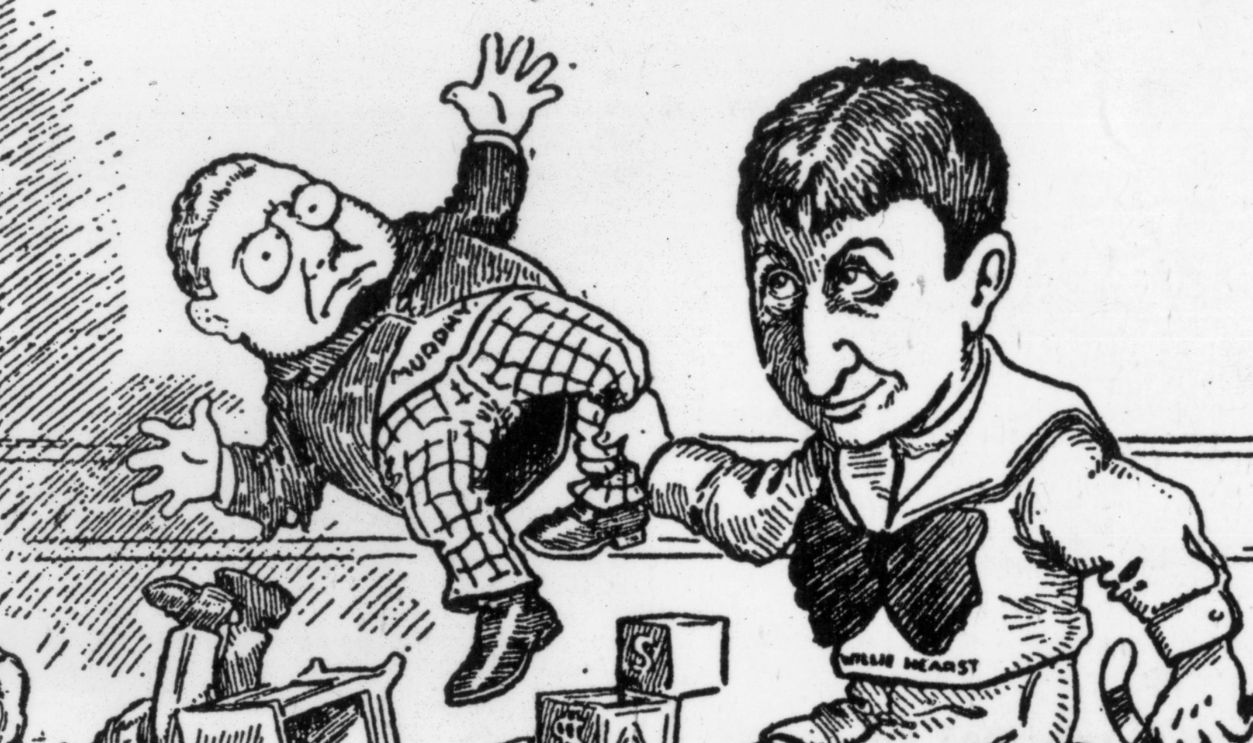

26. He Lost Election After Election…After Election

With the left-wing populists behind him, Hearst launched a bid for the Democratic nomination for president. However, he quickly learned that newspaper readers don’t necessarily make for reliable voters. Hearst lost his bid for the 1904 Democratic presidential nomination then went on to lose three more elections; two for mayor of New York and one for governor.

Even his own papers couldn’t help but make fun of him.

27. He Earned A Humiliating Nickname

After flaming out of every election post his Congressional career, Hearst’s critics gave him a scathing nickname: “William Also-Randolph Hearst”. The jab came courtesy of humorist Wallace Irwin and it stuck better than ink on gazette paper.

However, with or without political office, Hearst could still throw his weight around.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

28. He Stayed Out Of The War

Despite his humiliating election defeats, Hearst never stopped using his newspapers to air his opinions. He strongly opposed US entry into WWI, condemned the League of Nations, and even instructed his papers not to endorse a candidate in either the 1920 or 1924 elections. But he wasn’t quite done with politics just yet.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

29. He Made A Powerful Enemy

Hearst’s last real shot at political power came in 1922, when he sought the US Senate nomination in New York. However, he had made one particularly powerful enemy. New York governor Al Smith squashed Hearst’s bid—and earned Hearst’s undying enmity.

However, given Hearst’s later political views, Smith saved New York from a worse fate.

Douglas Volk (1856–1935), Wikimedia Commons

Douglas Volk (1856–1935), Wikimedia Commons

30. He Was Sympathetic To The Third Reich

Hearst once again shocked his critics and his readers alike when he voiced his sympathies with the rise of the Third Reich in Germany. According to historian Rodney Carlisle, Hearst disavowed the worst aspects of the new regime in Germany, but gleefully printed the fuhrer’s talking points in his newspapers.

In fact, he was a little too close to the fuhrer for comfort.

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

31. He Interviewed The Fuhrer

In 1934, Hearst caused another controversy when he traveled to Berlin to meet with the infamous leader of the Third Reich, face-to-face. When the dictator asked why the American press disliked him so much, Hearst famously quipped, “Because Americans believe in democracy, and are averse to dictatorship”.

Unless that dictatorship was in his own newsroom.

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

32. He Fired Journalists Who Didn’t Agree With Him

While Hearst extolled the benefits of democracy to the fuhrer in Germany, back home, he ruled his newsrooms with an iron fist. Hearst instructed his foreign correspondents to write pro-Third Reich pieces…or else. When reporters refused to toe the party line for moral reasons, he fired them.

In their place, he ran unchallenged propaganda from the likes of the Fuhrer, Göring, Mussolini, and other odious oligarchs across Europe and Latin America. Pretty soon, however, Hearst would at least have the sense to regret his decision.

33. He Finally Condemned The Third Reich

It took a terrible tragedy for Hearst to finally realize who he had been supporting. After Kristallnacht, Hearst changed his tune on the Third Reich, blaming the fuhrer and his party for the atrocity and accused him of turning “the flag of National Socialism [into] a symbol of national savagery”.

By that time, however, his personal reputation wasn’t much better than his professional one.

Unknown - Eisenach Stadt-Archiv (city-archive) or Center for Jewish history, NYC,, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown - Eisenach Stadt-Archiv (city-archive) or Center for Jewish history, NYC,, Wikimedia Commons

34. He Had A Full House

At the age of 40, Hearst finally gave up his bachelor lifestyle and settled down—at least on paper. He married 21-year-old chorus girl Millicent Veronica Willson in a ceremony fit for a media baron. Together, they had five sons and seemed like the perfect American family.

But behind closed doors, Hearst had other plans—and other partners.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

35. He Had His Cake (And Ate It, Too)

By the mid-1920s, Millicent had had enough. After years of enduring Hearst’s increasingly public affair with actress Marion Davies, she packed her bags. The two never officially divorced, though—they stayed married until Hearst’s passing decades later. Even though the collapse of his marriage scandalized his reputation, the arrangement seemed to suit Hearst just fine.

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

36. He Shacked Up With A Starlet

When Hearst wasn’t running a media empire, he was playing sugar daddy to Hollywood’s brightest starlet. He took up with Marion Davies, a comedic actress nearly 30 years his junior, and the two lived openly as a couple from 1919 onward. Political office might’ve eluded him, but he still had the power to pick his leading lady.

And the money to let her live in luxury.

37. He Gave His Mistress A Castle

Hearst had left his wife behind in a New York apartment to live with Davies in a mansion on the West Coast. But, what he really wanted was something even grander. After spotting St Donat’s Castle in a magazine, Hearst snapped up the historic Welsh property. He then proceeded to furnish it with priceless artefacts and allowed his mistress, Davies, to entertain the likes of Churchill and Chaplin at lavish parties.

He may have been trying to hide something even more scandalous.

38. He Had A Secret Daughter

For decades, Hearst and Davies carried a deep, dark secret. They had long paraded around the young and beautiful Patricia Lake as Davies’ “niece”. But, after her passing in 1993, family insiders revealed the shocking and scandalous truth about the mysterious Patricia Lake: she was actually Hearst and Davies’ daughter.

With so many kids, Hearst needed somewhere to house them all.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

39. He Built His Dream Mansion

As if a Welsh castle wasn’t enough, Hearst decided to build his own fantasy estate in California. Starting in 1919, he began construction on the historic Hearst Castle in San Simeon. He filled the sprawling property with imported art, antiques, and even Arabian horses.

Tragically, Hearst wouldn’t live to see his California castle completed—though there’s good reason for that.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

40. He Ran Out Of Ink—And Money

Between the castles, the art collections, and the papers, Hearst finally hit his financial limit in the 1930s. After the Great Depression wiped out his investments, his aggressive opposition to FDR and the New Deal turned his working-class readers against him. By 1937, Hearst was something he never thought he’d be: broke!

What he had to do next was flat out embarrassing.

National Archives Photo, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives Photo, Wikimedia Commons

41. He Turned Down A Kennedy

As Hearst watched his fortune slip away, he had an unlikely opportunity to save part of his crumbling empire. His friend, Joseph P Kennedy, offered to buy his struggling magazines. But Hearst, too proud and possessive, refused. Instead, he mortgaged off his prized San Simeon estate for a cool $600,000.

Unfortunately, that wasn’t nearly enough.

42. He Sold Everything Off

By the late 1930s, despite his best efforts to salvage his empire, Hearst’s finances were in freefall. He had racked up tens of millions in debt, his movies were losing money, and Davies’ star power wasn't enough to save him. Desperate, he let go of most of his staff, sold his exotic animals, and turned over control of his finances (or what was left of them) to a trustee.

Then he really got desperate.

43. He Took Money From His Mistress

No matter how bad things got for Hearst, he wouldn’t sell his beloved newspapers—not even to save himself from ruin. Instead, he took a humiliating lifeline from his mistress, Davies, who pawned her jewelry and tapped her contacts to raise $2 million. To make matters worse, Hearst had to pay rent to live in his own castle.

He was still king—but not of much.

44. He Sold Off His Legacy

Hearst technically avoided bankruptcy, but no one was fooled. His warehouses were emptied, his antiques auctioned, and even his prized collections at St Donat’s were picked through. In one particularly painful episode, John D Rockefeller Jr bought up $100,000 worth of Hearst’s silver then donated it to a museum.

45. He Became A Charity Case

Once the most powerful media mogul in America, Hearst ended up the butt of his friends’ jokes. George Loorz, once close to Hearst, cruelly remarked that the old magnate wanted to finish construction on his castle pool but “hasn’t got the money”. He then quipped, “Poor fellow, let's take up a collection”.

The humiliation wasn’t over yet.

Library of Congress, Getty Images

Library of Congress, Getty Images

46. He Nearly Lost His Castle

By 1939, Hearst’s fall from grace had become so public that even Time magazine took notice. The article revealed a particularly humiliating detail: Hearst was on the verge of defaulting on his mortgage for his San Simeon castle. It was only the mercy of his rival, Harry Chandler, that saved him. Chandler extended the repayment and let Hearst keep his castle.

In the end, Hearst would at least have the last laugh.

King of Hearts, Wikimedia Commons

King of Hearts, Wikimedia Commons

47. He Staged A Comeback

Hearst’s empire had crumbled during the Depression years, but he was about to stage a legendary comeback. As America mobilized for WWII, ad revenue surged and the Hearst Corporation bounced back. Hearst, who had been holed up at his other estate Wyntoon, triumphantly returned to San Simeon in 1945.

He even resumed his philanthropic endeavors, donating art to museums to restore his image. Even if only for a short time.

48. He Passed Far From Home

As Hearst’s empire rebounded, his health declined, and the remote location of San Simeon posed a problem. In 1947, he left his beloved estate to seek medical care in Beverly Hills. Sadly, it would be the last move he would make. On August 14, 1951, William Randolph Hearst succumbed to his illnesses at the age of 88.

His legacy, however, would live on in infamy.

49. He Inspired Citizen Kane

Some years before his passing, Hearst got a preview of what his legacy would look like when he learned about Orson Welles’ 1941 masterpiece Citizen Kane. Welles had taken obvious inspiration for the film’s titular anti-hero from Hearst’s life. Though the title character was a fictional composite, many saw it as a thinly veiled takedown of the media mogul.

It would be Hearst’s last fight.

50. He Tried To Bury Citizen Kane

Hearst never saw Citizen Kane, but he hated it all the same. Using the restored power of his media empire, Hearst tried to crush the film before it ever saw the inside of a movie theater. While Welles and RKO resisted, Hearst’s Hollywood allies pressured theaters to blacklist the movie—and it worked.

Citizen Kane underperformed at the box office, but became a classic in the ensuing decades, forever cementing Hearst’s legacy as a ruthless media mogul.

You May Also Like:

Enzo Ferrari Lived Fast And Died Angry

Alan Rickman Was Hollywood’s Favorite Villain