Footsteps To Freedom

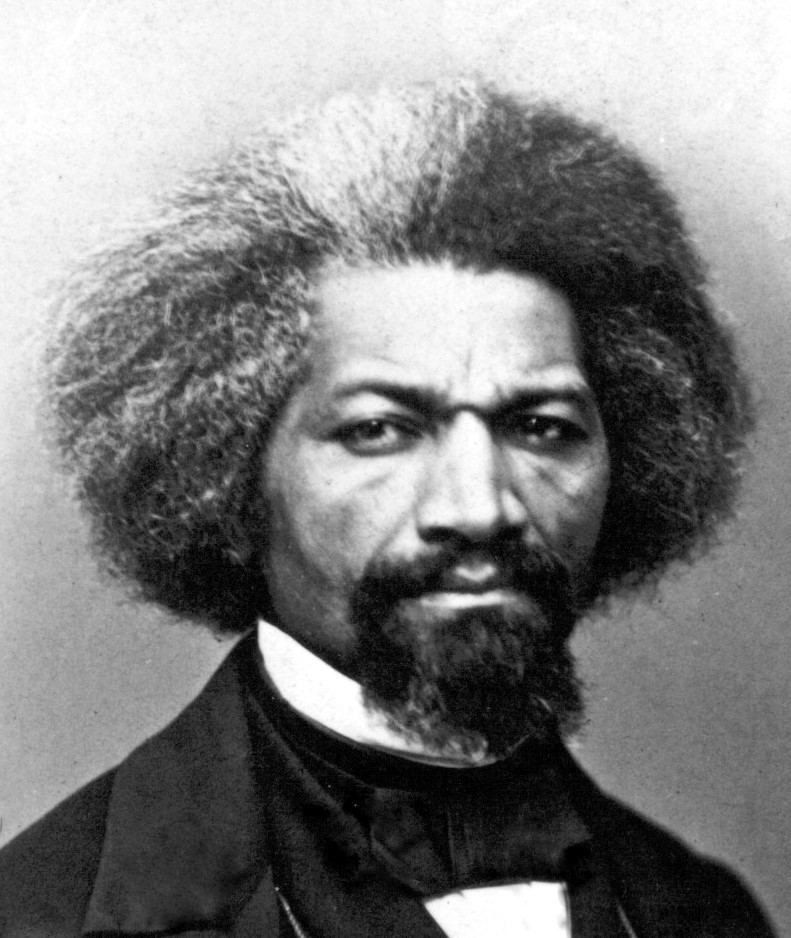

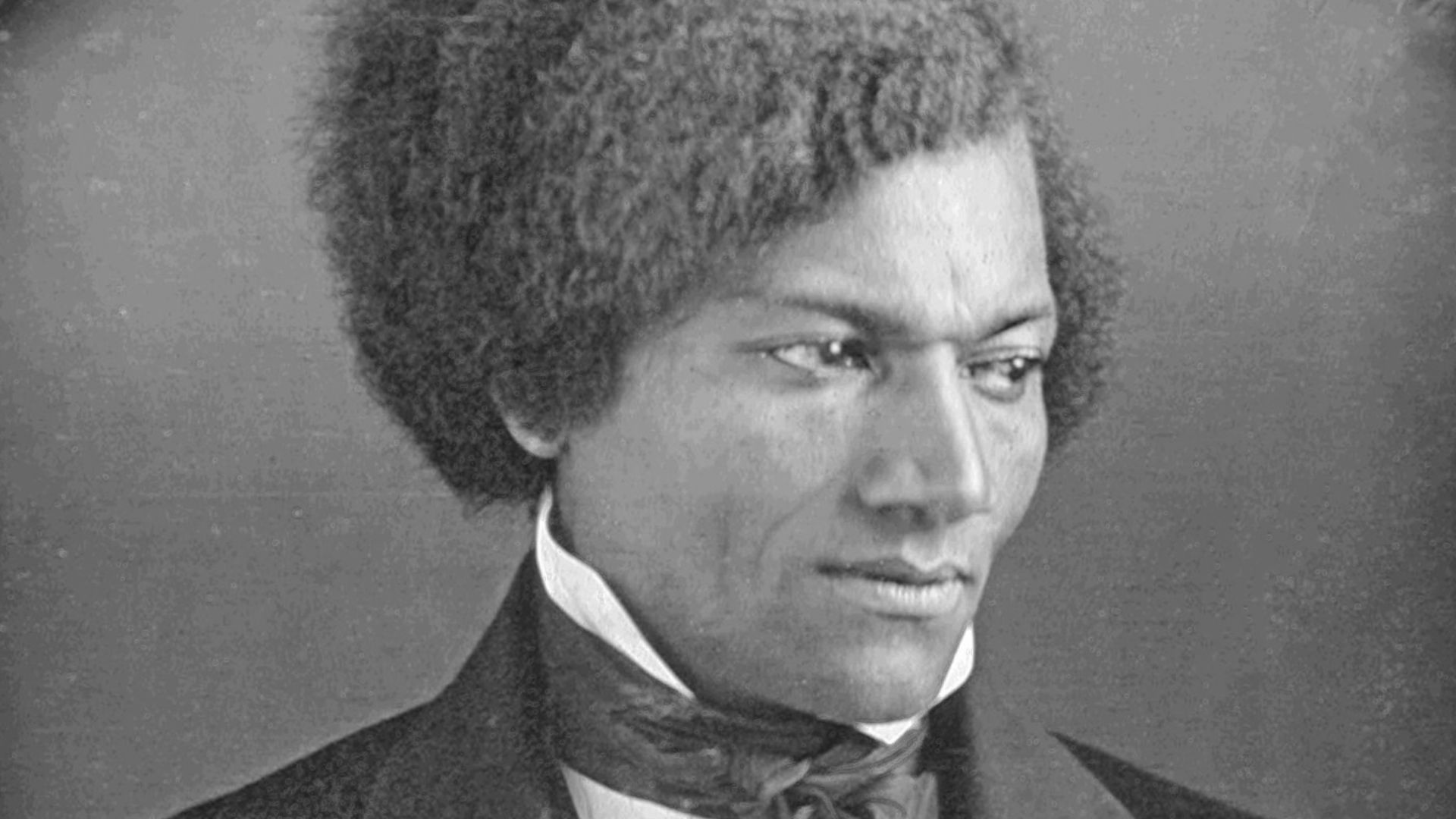

Frederick Douglass’s escape from slavery in 1838 was a carefully planned act of courage shaped by years of planning, education, disappointments, and close calls. His trek out of bondage in Maryland to an uncertain liberty in New York reveals the risks he ran, the strategies he used, and the fear that dogged his footsteps long after he made it to the North.

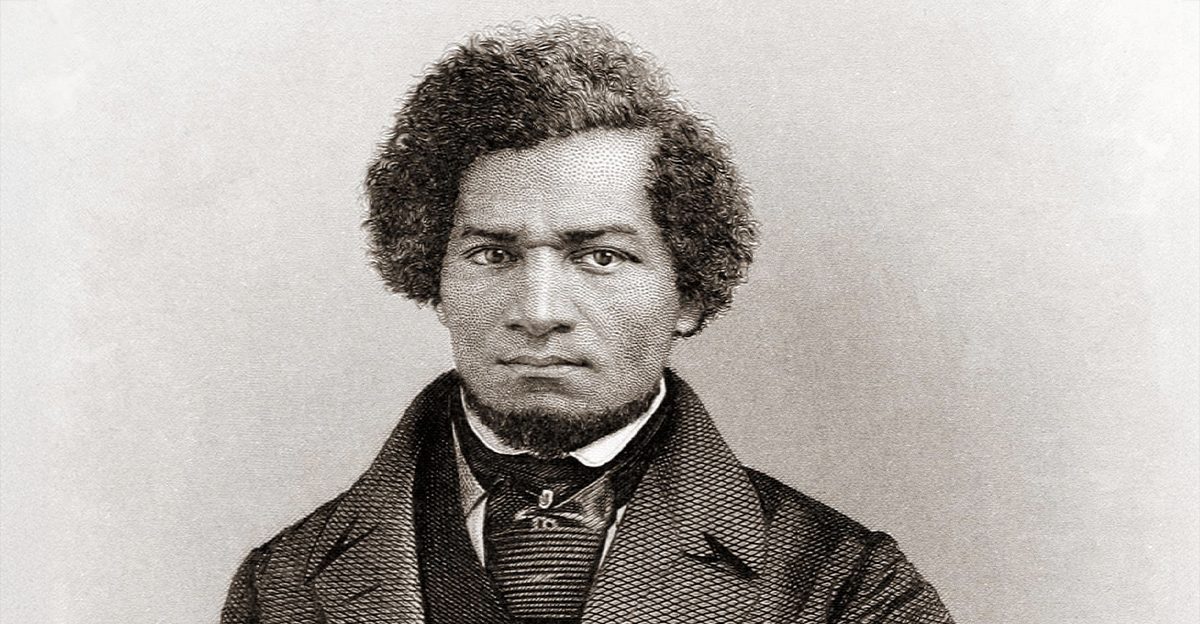

Engraved by J.C. Buttre, Wikimedia Commons

Engraved by J.C. Buttre, Wikimedia Commons

Born Into Slavery In Maryland

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born enslaved in Talbot County, Maryland, around 1818. Separated from his mother as an infant, he grew up under the ongoing threat of violence and family fragmentation. From the earliest days of his childhood, he bore witness to the harsh realities of slavery, experiences that planted deep seeds of resistance and an unquenchable longing for freedom.

Preservation Maryland, Wikimedia Commons

Preservation Maryland, Wikimedia Commons

Early Exposure To Literacy

When Douglass was sent to Baltimore as a child, his owner’s wife briefly started to teach him the alphabet. Though her husband quickly stepped in and put a stop to any further instruction, Douglass got far enough along the road to literacy to be able to recognize it as a pathway to liberation. He continued learning in secret by observing white children and practicing reading every chance he got.

A Means Of Resistance

Douglass traded bread with local white boys in exchange for reading lessons. As time went on, he became literate enough that he could read newspapers and anti-slavery writings. These texts only made his awareness and sense of injustice that much stronger. It not only convinced him that slavery wasn’t a natural state of affairs, but that its days were numbered.

First Escape Attempt

By 1836, Douglass had started planning a group escape with several of his fellow enslaved men. They created forged passes and selected a day to depart. But this plan was betrayed before they could even start to carry it out. Douglass was arrested along with the others.

Arrest And Close Confinement

After this first failed attempt, Douglass was jailed and interrogated. Though the authorities strongly suspected that Douglass had a leading role as organizer, they lacked definitive proof. Eventually they released him back to his owner. Douglass glumly realized he was right back where he started from. He also faced increased scrutiny and the grim possibility of being sold even deeper into the South, from where escape would be next to impossible.

Transfer Back To Baltimore

To reduce tension following the failed escape, Douglass was returned to Baltimore. There, he toiled in shipyards and learned skilled trades. This bustling urban environment offered him a relative degree of mobility compared to the static, remote nature of plantation life. These were conditions that would later make it much easier for him to make his final escape.

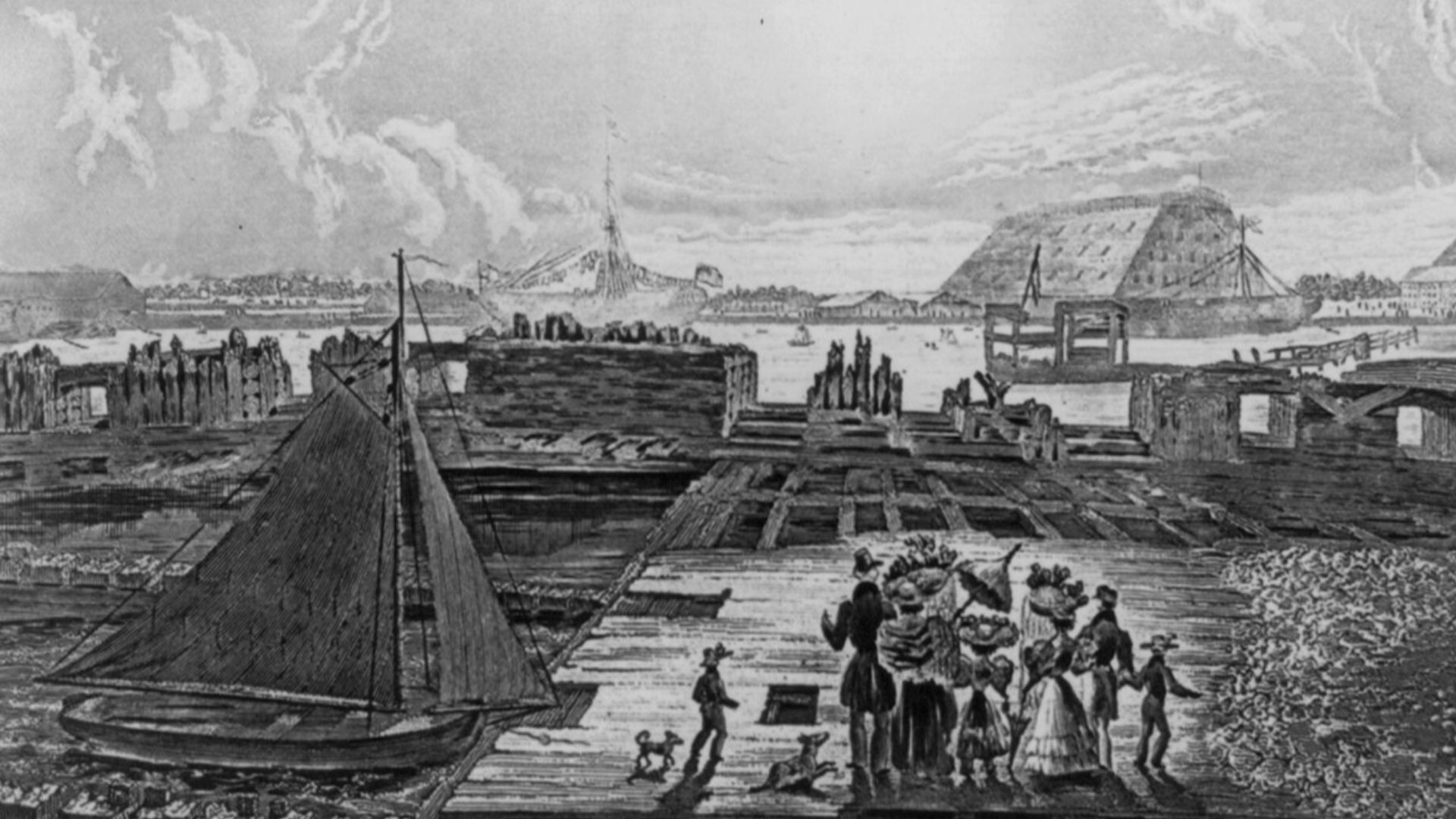

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Securing Maritime Skills

Working as a caulker in Baltimore’s busy shipyards gave Douglass access to maritime culture and vocabulary. As he witnessed free Black sailors carrying official documents around the area, an idea took root in his mind and began to grow. He realized that sailor identification papers might serve as a great disguise for travel northward into non-slave territory.

National Maritime Museum from Greenwich, United Kingdom, Wikimedia Commons

National Maritime Museum from Greenwich, United Kingdom, Wikimedia Commons

He Borrowed Identification Papers

Douglass surreptitiously obtained identification papers from a free Black sailor. While the image and other information on the papers didn’t really fit his description very well, they provided a critical layer of credibility with officialdom. Their mere existence allowed him to board transportation without immediately causing any suspicion.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Disguised As A Sailor

On September 3, 1838, Douglass dressed in a red shirt, tarpaulin hat, and a sailor’s attire. The clothing helped reinforce his assumed identity. His confidence and composure were essential, since any visible signs of nervousness would bring unwanted attention, and possibly even trigger his immediate arrest. The consequences of that, Douglass didn’t even want to think about.

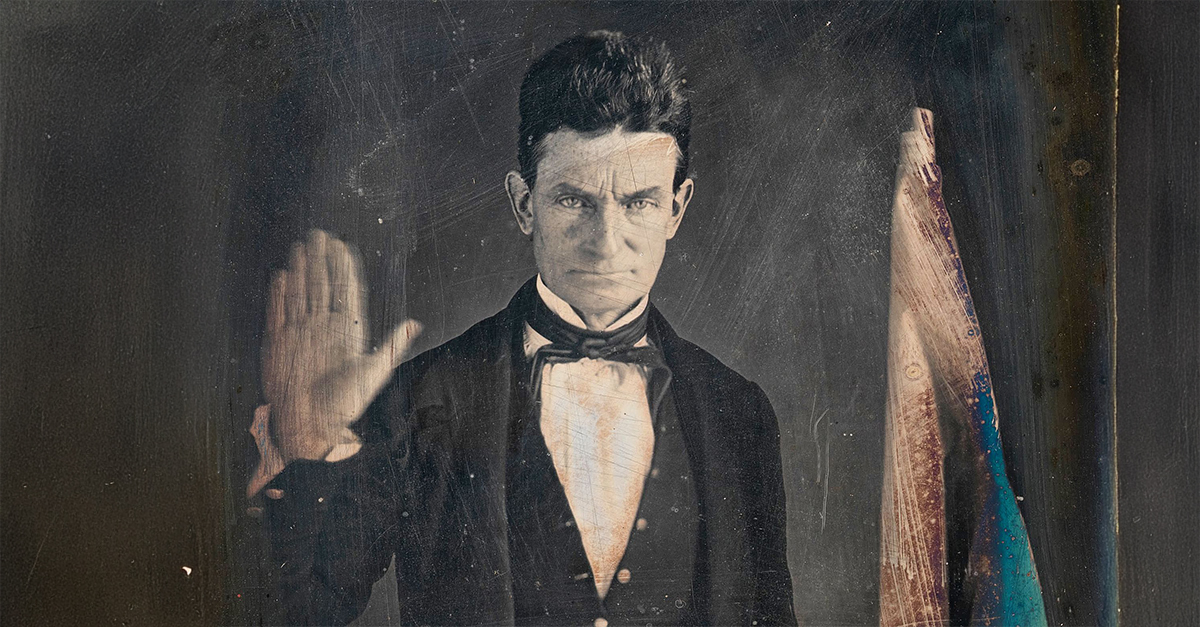

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Boarding The Train In Baltimore

Douglass boarded a train of the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore Railroad. Ths was the real moment of truth. Conductors regularly checked identification, and his capture would have brought severe punishment down on him. The conductor asked Douglass for his papers. It was now or never. Douglass briefly and nonchalantly presented them. Time came to a standstill.

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company, Wikimedia Commons

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company, Wikimedia Commons

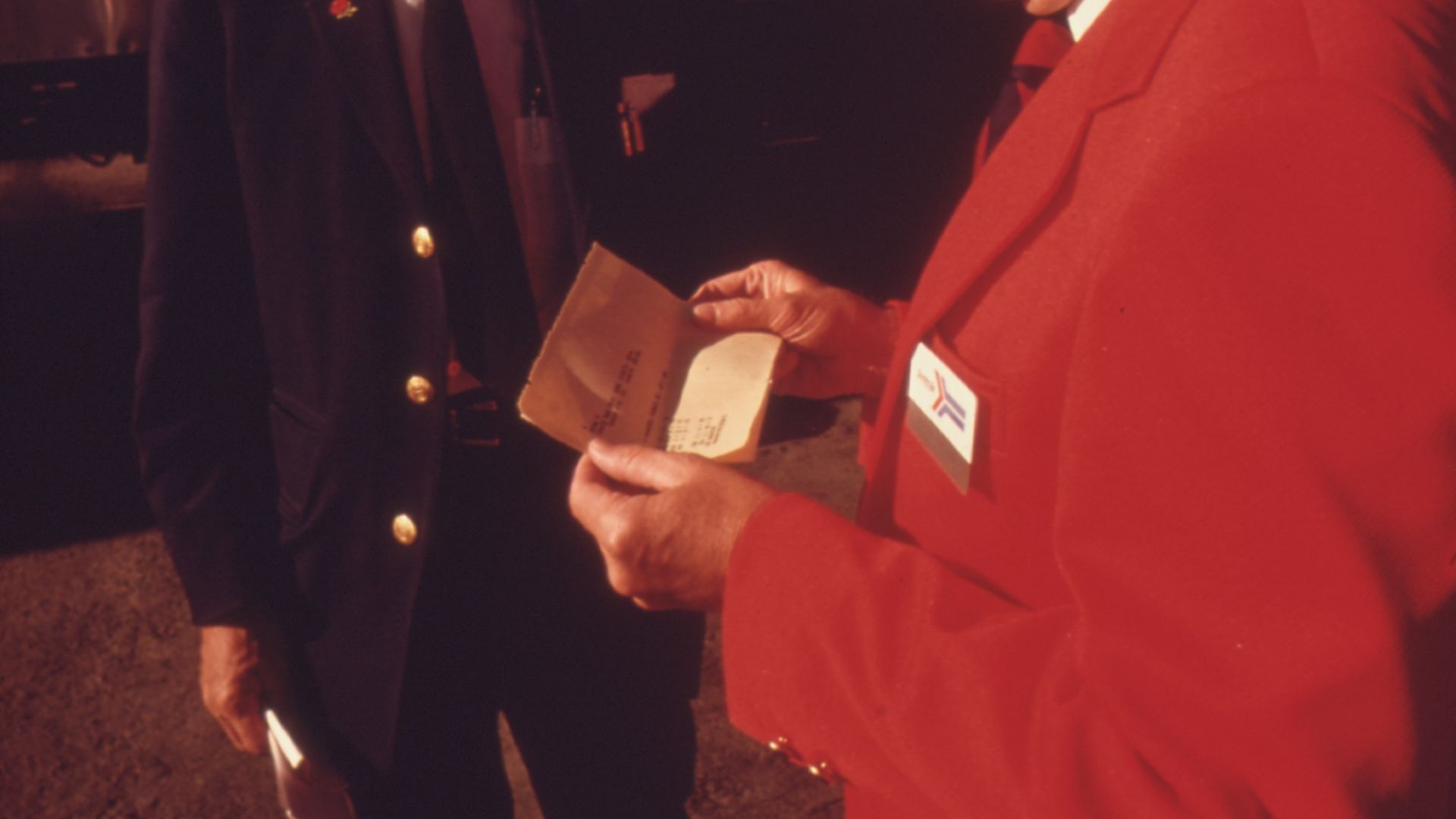

A Narrow Escape From Inspection

The conductor scrutinized Douglass’s documents but didn’t examine them long enough to detect any discrepancies. Douglass later described that moment as intensely nerve-racking. Had the conductor lingered or questioned him any further, the escape attempt would’ve ended right then and there. But the conductor handed the papers back without another word, and went on his way.

Charles O'Rear, Wikimedia Commons

Charles O'Rear, Wikimedia Commons

Crossing Into Free Territory

Douglass’s journey was far from over. It required multiple segments, including ferry boats and rail connections through Delaware. Each transfer meant another potential exposure to inspection. Nevertheless, he kept going steadily northward, perfectly well aware that he was still within reach of slave catchers throughout the trip.

Richard from USA, Wikimedia Commons

Richard from USA, Wikimedia Commons

He Reached New York City

After roughly 24 hours of travel, Douglass finally arrived in New York City. He had reached a free state, and he was physically free. But he was still in a highly vulnerable situation legally. His palpable sense of relief at completing the trip was immediately replaced by a gnawing anxiety about surveillance and betrayal.

Hippolyte Sebron, Wikimedia Commons

Hippolyte Sebron, Wikimedia Commons

He Was Still Afraid

Though New York was a free state, under federal law slave catchers could roam and operate freely in Northern cities. Douglass feared that anyone might question his status or expose him. He later recalled the unpleasant memory of feeling like a hunted animal despite his arrival in free territory.

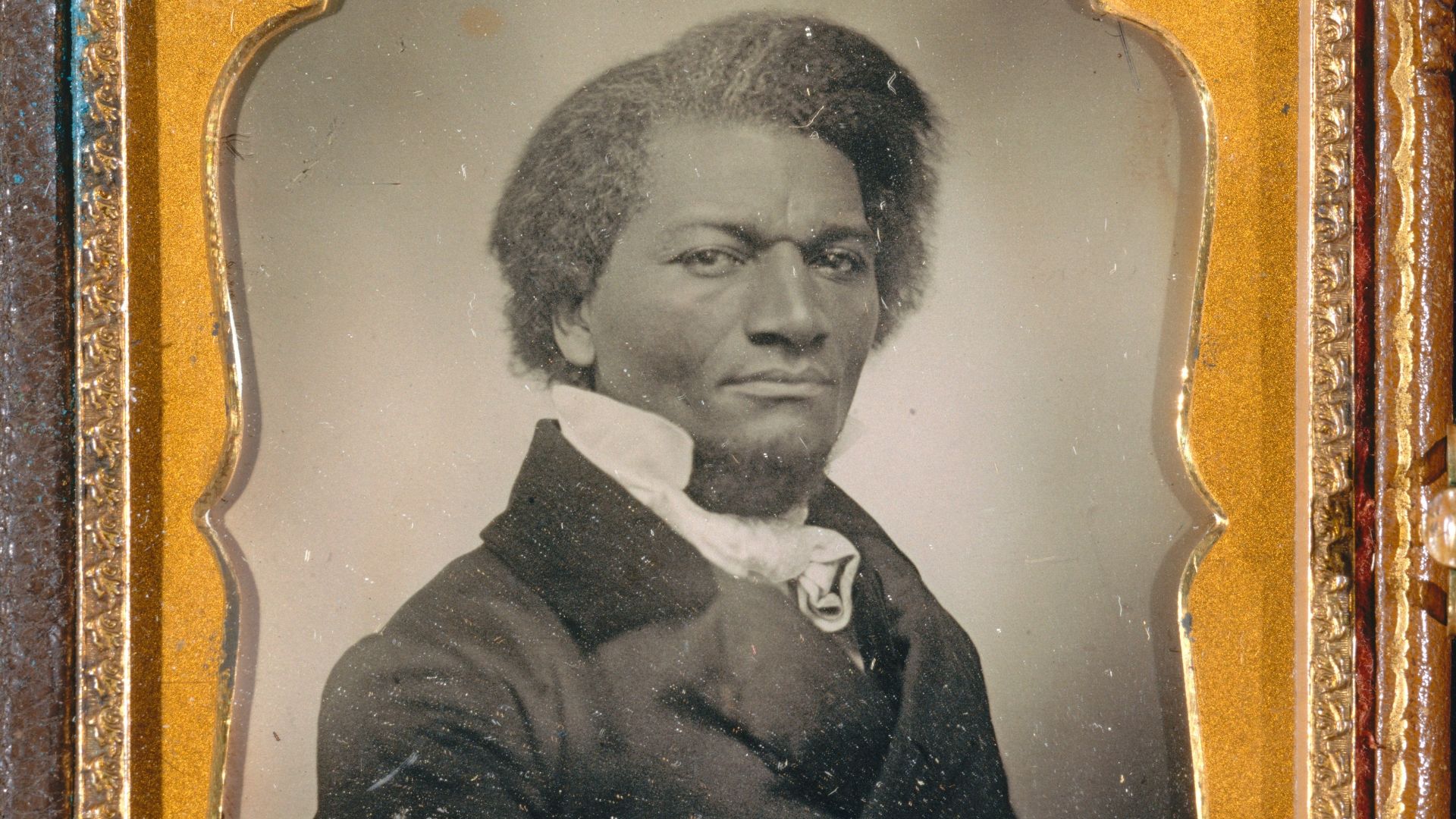

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Abolitionists Helped Him

Douglass sought help from David Ruggles, a free Black abolitionist who aided slaves on the run from their Southern masters. Ruggles gave Douglass shelter, guidance, and a wealth of important connections. This assistance was critical, as Douglass had arrived in New York with no money in his pocket, didn’t know anyone from Adam, and had no plan of staying safe.

Marriage To Anna Murray

Shortly after reaching New York, Douglass reunited with Anna Murray, a free Black woman he had met during his time working in the shipyards in Baltimore who had given him some of her own money to help him escape. The two married in September 1838. Their union symbolized a much-needed personal stability and a shared commitment to a new life in freedom.

Photograph first published in Rosetta Douglass Sprague,

Photograph first published in Rosetta Douglass Sprague,

He Relocated To New Bedford

To reduce the risk of capture, Douglass and Anna moved to the whaling town of New Bedford, Massachusetts, which had also become a major center for the abolition of slavery. The city had a big active abolitionist community and few connections to Maryland slaveholders. There, Douglass adopted a new surname to mask his former identity.

Jack Delano, Wikimedia Commons

Jack Delano, Wikimedia Commons

Living Under A New Name

Frederick Bailey now became Frederick Douglass in New Bedford. Changing his name provided him with an additional buffer against capture. Even so, fugitive slave laws meant he could still legally be seized if anyone made a positive identification of him, and this knowledge fed his ongoing caution. Douglass wasn’t leaving anything to chance.

Robert M. Cargo (American, 1828-1902), Wikimedia Commons

Robert M. Cargo (American, 1828-1902), Wikimedia Commons

The Anxiety That Wouldn’t Go Away

Douglass wrote years later that even in the supposedly safe state of Massachusetts, he never felt completely secure. Newspapers were constantly printing descriptions of fugitives, and bounty hunters traveled far north in search of rewards. Every unfamiliar face carried with it the potential for danger.

He Drew Strength From Community

Integration into the abolitionist movement gradually eased Douglass’ worries and gave him a growing sense of confidence. Attending anti-slavery meetings gave him the opportunity to meet and hear others’ views; he soon took to public speaking and activism himself. This social context buzzing with forward-thinking energy and vision allowed him to shift from fugitive to advocate. He was on a path that he would follow for the rest of his life.

Luke C. Dillon (photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Luke C. Dillon (photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Public Testimony About Slavery

In 1841, Douglass gave a powerful speech at an antislavery convention. His firsthand account electrified audiences. His transformation from enslaved laborer to public orator was proof of his intellectual development and personal strength. All those difficult years teaching himself to read had made Douglass a powerful voice for the abolition of slavery, one unlike any the abolitionists or the larger American public had ever heard before.

daveynin from United States, Wikimedia Commons

daveynin from United States, Wikimedia Commons

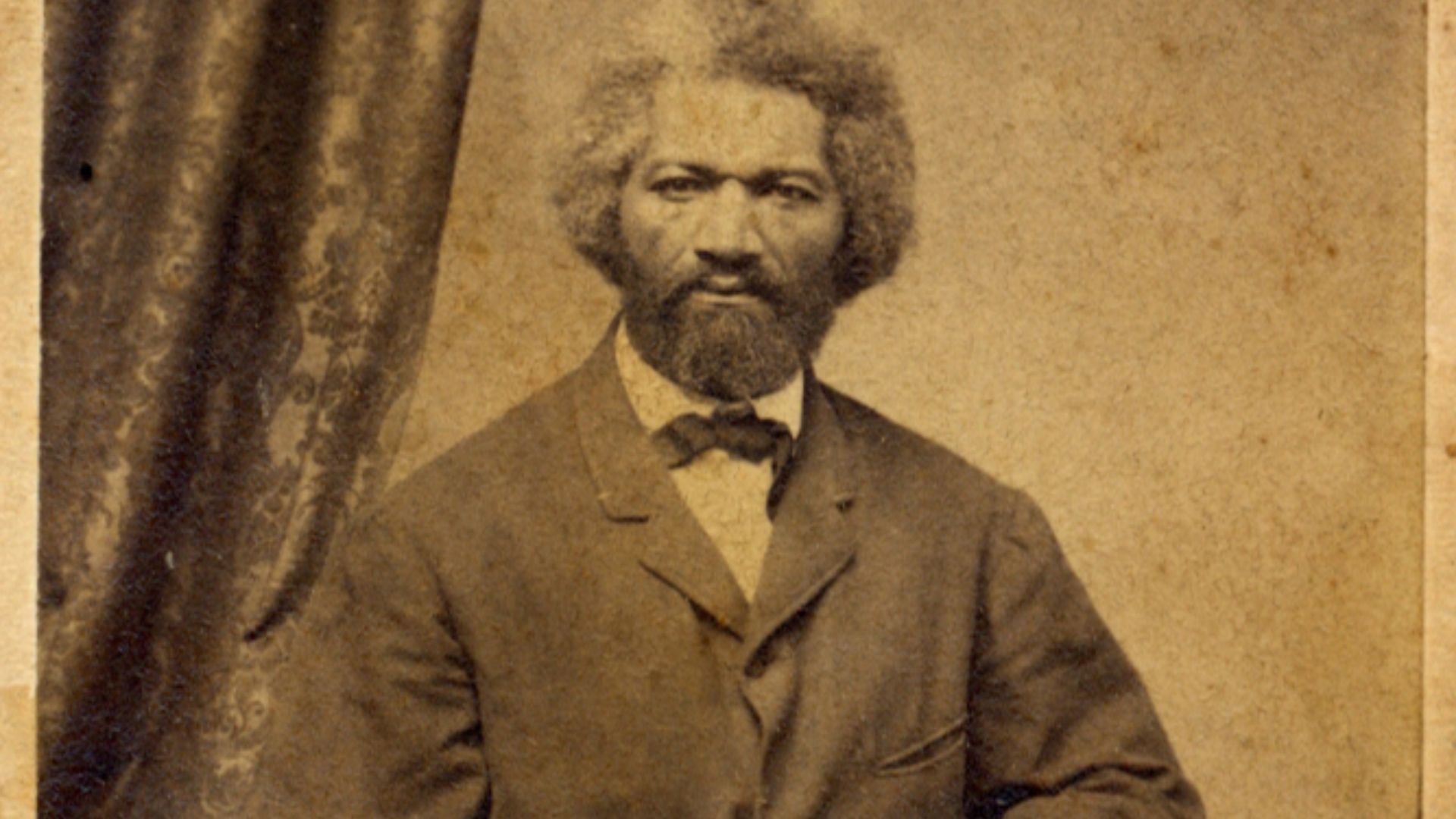

Publication Of His Narrative

In 1845, Douglass published Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. The book detailed his escape and earlier experiences in harrowing detail. No one who traversed its pages could any longer deny the horror of slavery. The book’s success made him an internationally known figure, but also increased the risk that former enslavers could identify him.

Frederick Douglass, Wikimedia Commons

Frederick Douglass, Wikimedia Commons

He Went Overseas

Realizing that his new notoriety also brought a heightened risk of recapture, Douglass decided to travel to Britain and Ireland. Supporters there raised funds to help Douglass purchase his legal freedom. This formal step, as absurd as it seems now, was really the only avenue open to him to permanently remove the threat of his recapture under American law.

Cornelius Marion Battey, Wikimedia Commons

Cornelius Marion Battey, Wikimedia Commons

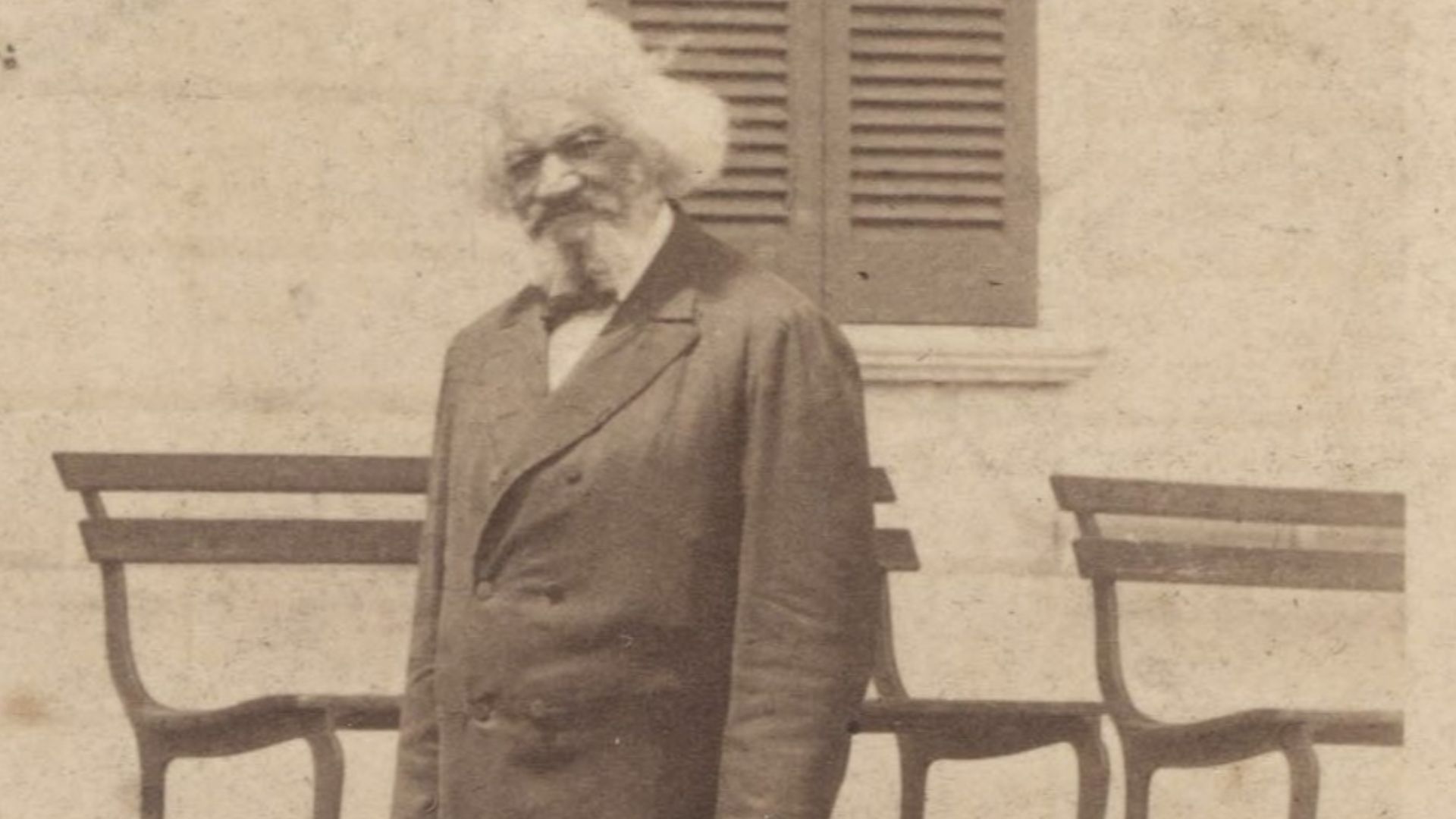

Freedom Secured

In 1846, Douglass’s freedom was formally purchased. Abolitionists contacted his former owner Hugh Auld, and paid 150 pounds sterling (roughly $30K US in today’s currency) for Douglass’ manumission. Though it was controversial with some abolitionists, this arrangement made certain that he would no longer be legally vulnerable to any claims by former enslavers. The security allowed him to focus fully on his writing and activism.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

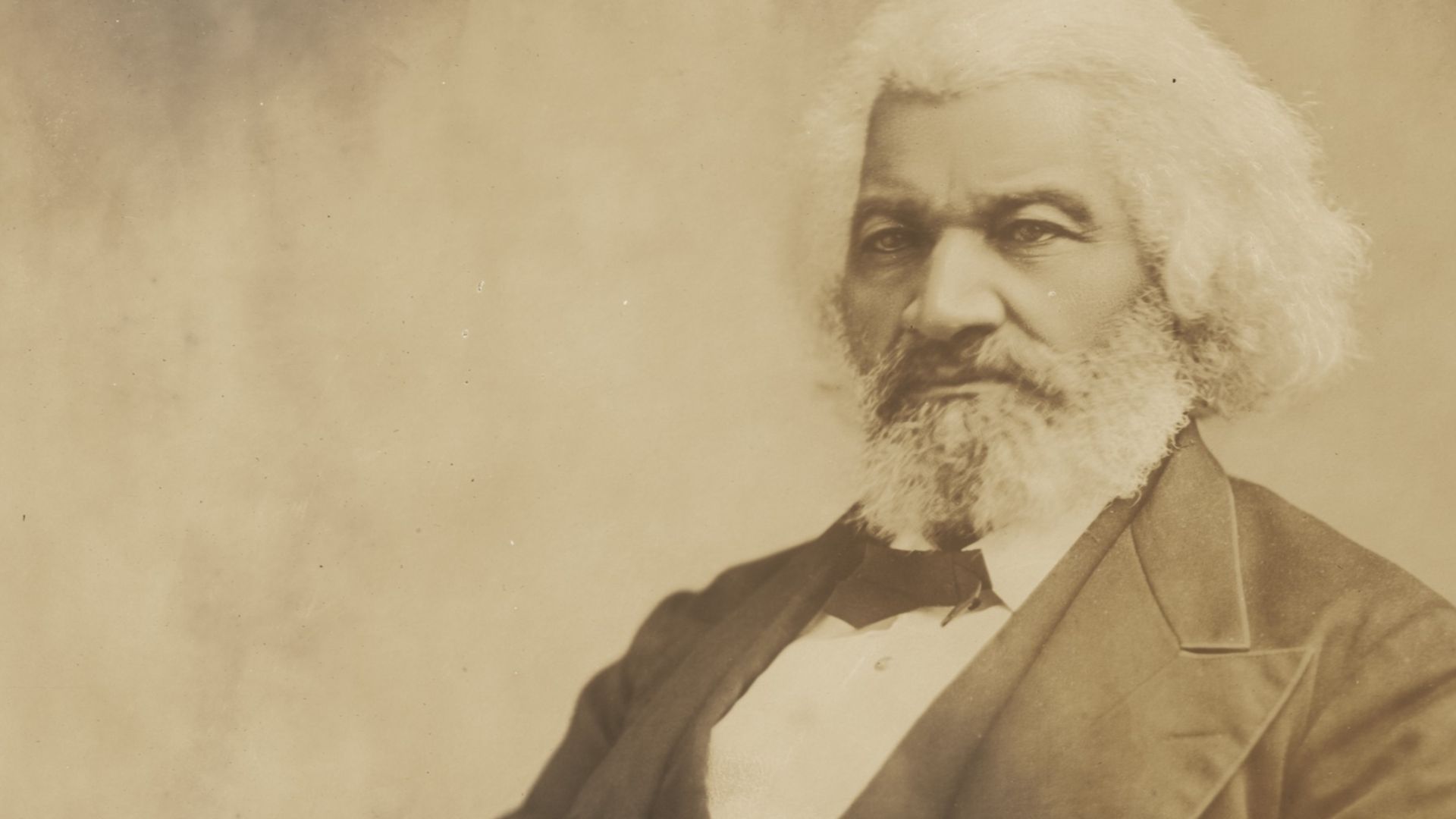

Legacy Beyond Escape

Frederick Douglass went on to become one of the nineteenth century’s most influential writers, editors, and public speakers. His eloquent speeches and powerful autobiographies shaped national conversations about slavery, citizenship, and equality. But none of it would have ever materialized without the courageous journey he made from bondage to freedom.

You May Also Like:

Liberating Facts About Harriet Tubman, The American Emancipator

Dred Scott’s Quest For Freedom