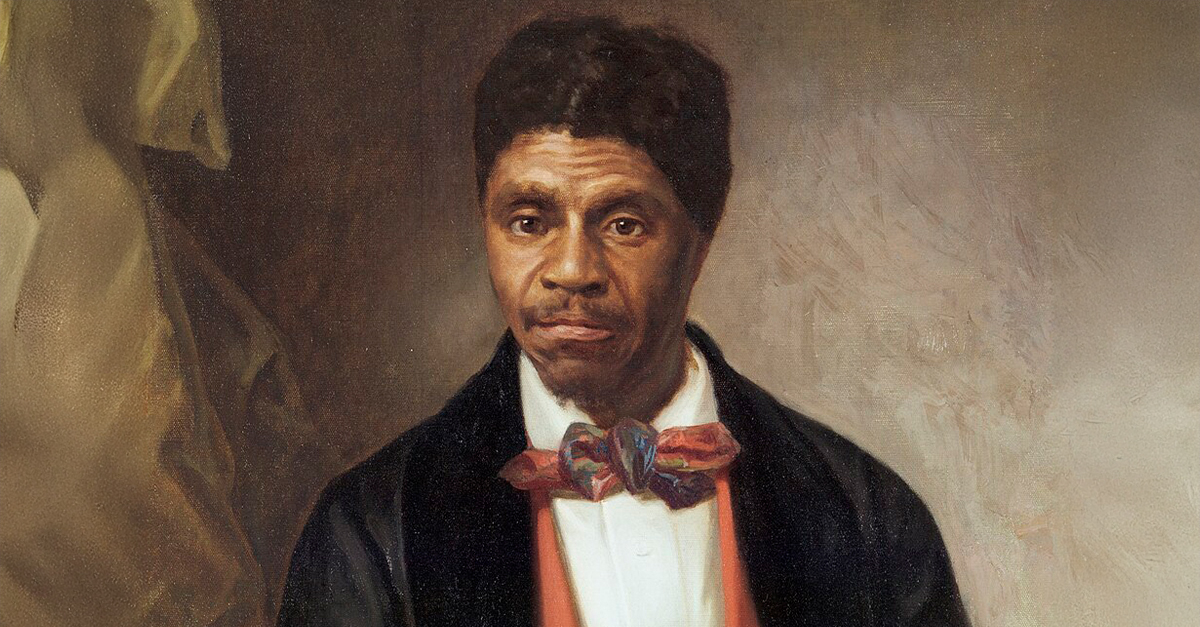

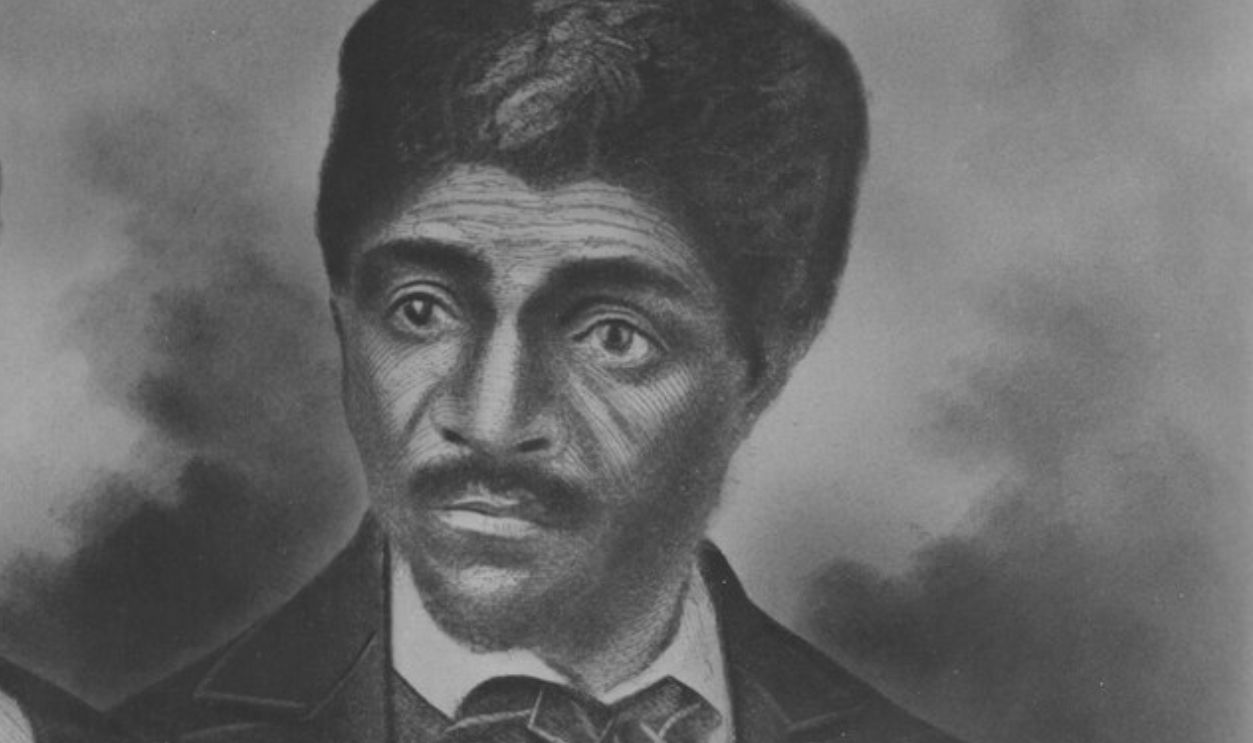

The Slave Who Changed History

Born into slavery and moved constantly across a chaotic nation, Dred Scott’s life drifted on the currents of shifting laws, military posts, and bitterly contested ideas about freedom. Long before his name arrived in the Supreme Court, Scott’s life showed how slavery operated across borders, territories, and jurisdictions. His story is best followed as a chain of relocations, ownership changes, and legal decisions.

Born Into Slavery

Dred Scott was most likely born around 1799 in Virginia, a slave state where enslaved status was inherited at birth. As with most slaves, documentation of his early years is scarce; there simply weren’t much records kept about enslaved people. By the early nineteenth century, Scott would be sold westward as the American frontier ballooned outward.

Sold To The Missouri Frontier

Scott belonged to Peter Blow, who moved his family and slaves from Virginia to Alabama to farm. Blow gave up farming in 1830 and moved to St. Louis, Missouri, a state that had entered the Union as a slave state in 1821. Scott’s forced relocation placed him within a border state where the slavery controversy would burn ever hotter as the years went by.

Henry Lewis, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Lewis, Wikimedia Commons

Ownership Transfers After Blow’s Death

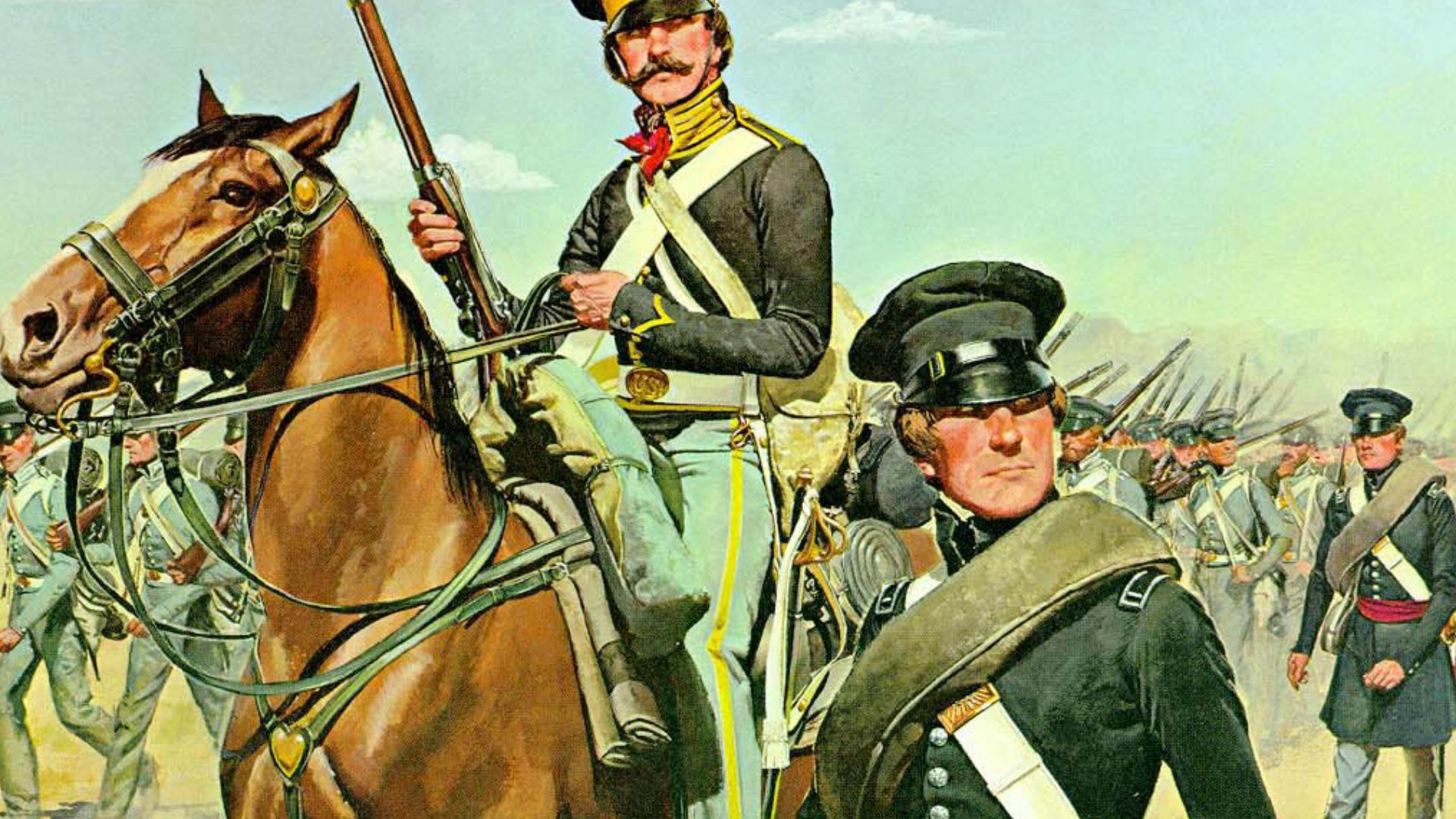

After Peter Blow died in 1832, Scott was sold to Dr. John Emerson, a surgeon in the U.S. Army. This change in ownership was a major turning point, as Emerson’s military assignments would eventually carry Scott along with him across state and territorial boundaries.

Transported To A Free State

In 1834, Emerson brought Scott to Illinois, a free (non-slaveholding) state under the laws of that era. Scott toiled in Illinois for several years. This fact would loom large because Scott’s residence in a free state was often cited in later legal claims to freedom.

Relocated To Wisconsin Territory

In 1837 Dr. Emerson took Scott to Fort Snelling in the Wisconsin Territory, where slavery was prohibited by federal law. Though he continued to work under Emerson’s ownership, his extended residence in the Wisconsin territory would become one of the strongest factual pillars of his future lawsuit to become a free man.

Marriage To Harriet Robinson

While living at Fort Snelling, Scott married Harriet Robinson, a slave owned by Lawrence Taliaferro. A justice of the peace, Taliaferro presided over the slave couple’s civil ceremony. The marriage would also figure importantly in the later court case, as it was submitted as evidence that Scott was being treated as a free man, and not as a slave, whose marriages weren’t recognized by law.

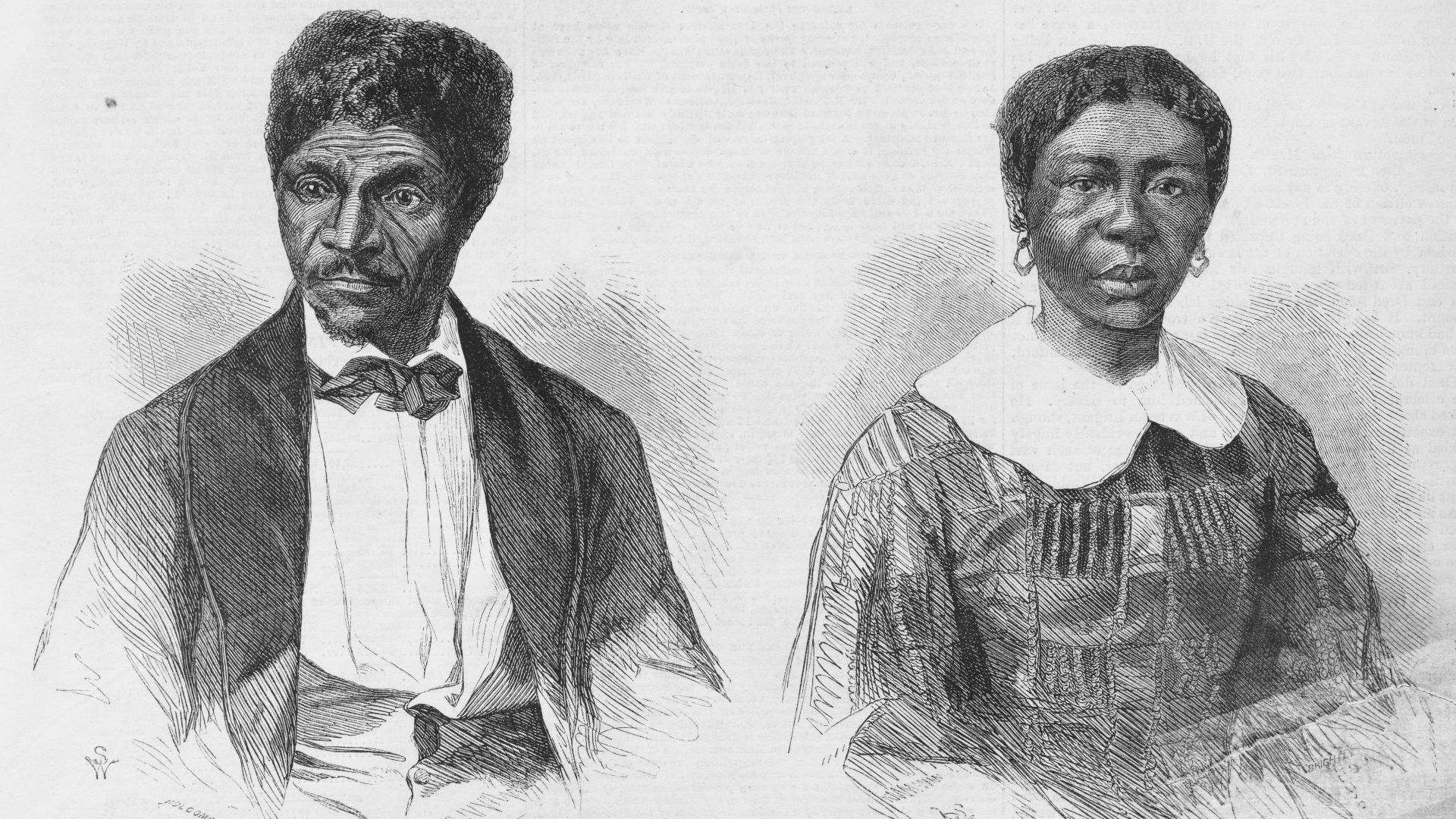

Wood engravings after photographs by Fitzgibbon, St. Louis, Wikimedia Commons

Wood engravings after photographs by Fitzgibbon, St. Louis, Wikimedia Commons

Emerson On The Move

Taliaferro transferred ownership of Harriet to Emerson. Meantime, Emerson himself was reassigned to the southern slave state of Louisiana. There he married Eliza Irene Sanford. Then Emerson was reassigned back to Fort Snelling in Wisconsin. Meanwhile the Scott family was growing.

Children Born On Restricted Soil

Dred and Harriet Scott had two daughters during this time, Eliza and Lizzie. The girls were born during times when the family lived in free territory or free states. The good fortune of being born in free states could give them the chance of inheriting free status themselves.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Return To Missouri

In 1840, Emerson moved back to Missouri with the Scotts. Despite the Scott family’s prior residence in free areas, Missouri authorities went on treating them as slaves, eradicating any practical recognition of their time on prohibited soil. It was as if their time in Wisconsin hadn’t happened. A black person was a slave as soon as he set foot in a slave state, as the logic went.

Emerson’s Death And His Estate

Dr. Emerson left the army in 1842 and died the following year. Scott and his family now became part of his widow’s estate. But instead of letting him go free, Irene Emerson hired Scott out for wages. This meant that Scott continued on in slavery while she, Emerson, collected all the wages from his work. This state of affairs went on for three years.

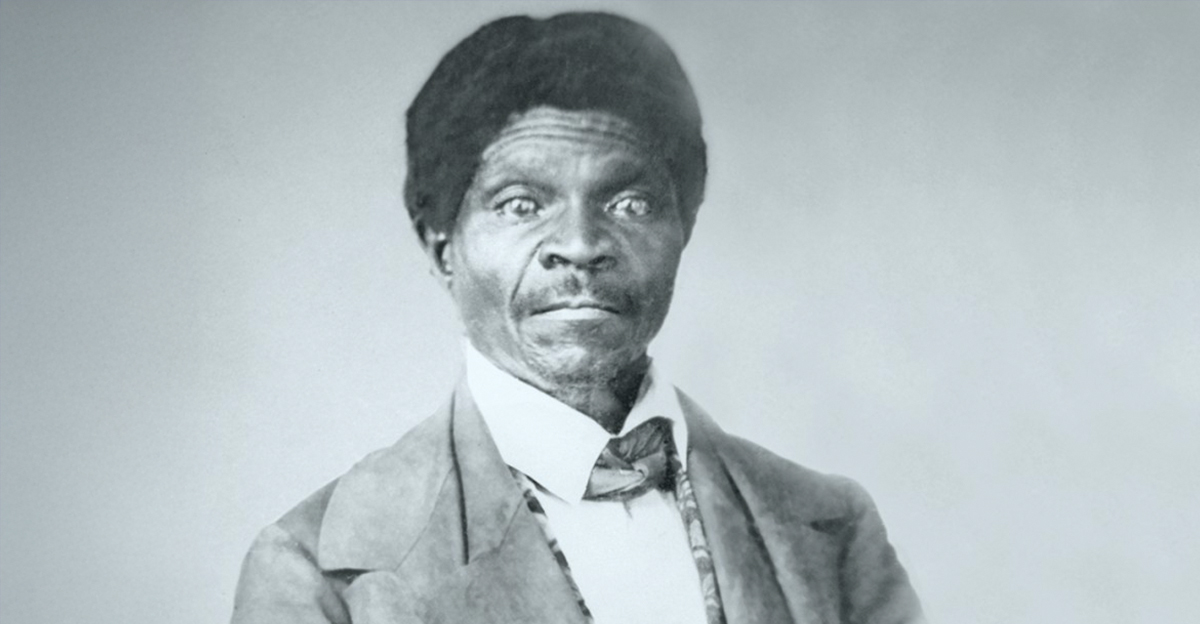

Schultze, Louis, Wikimedia Commons

Schultze, Louis, Wikimedia Commons

First Attempts To Buy Freedom

Scott first attempted to purchase his family’s freedom from Irene Emerson. He offered her the not insignificant sum of $300, (more than $10K in today’s money). After these efforts came up empty, Scott set his sights on Missouri’s legal system, which surprisingly allowed enslaved people to sue for their freedom under highly restricted circumstances.

unidentified artist, Wikimedia Commons

unidentified artist, Wikimedia Commons

The First Freedom Suit

In 1846, Scott formally filed a lawsuit for freedom in Missouri state court. His claim was built on his past residence in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, where he was considered a voluntary servant of the Emersons. This, they submitted to the court, made him a free man under established legal precedent, known as the “once free, always free” principle.

An Initial Court Loss

The trial took over a year to start, and once the proceedings got underway in 1847 in St. Louis, they didn’t go well. Scott lost his first case on technical grounds, as the court ruled that he’d failed to legally establish proof of his ownership by Irene Emerson. It was a disappointment, but the judge called for a retrial, keeping Scott’s legal fight alive.

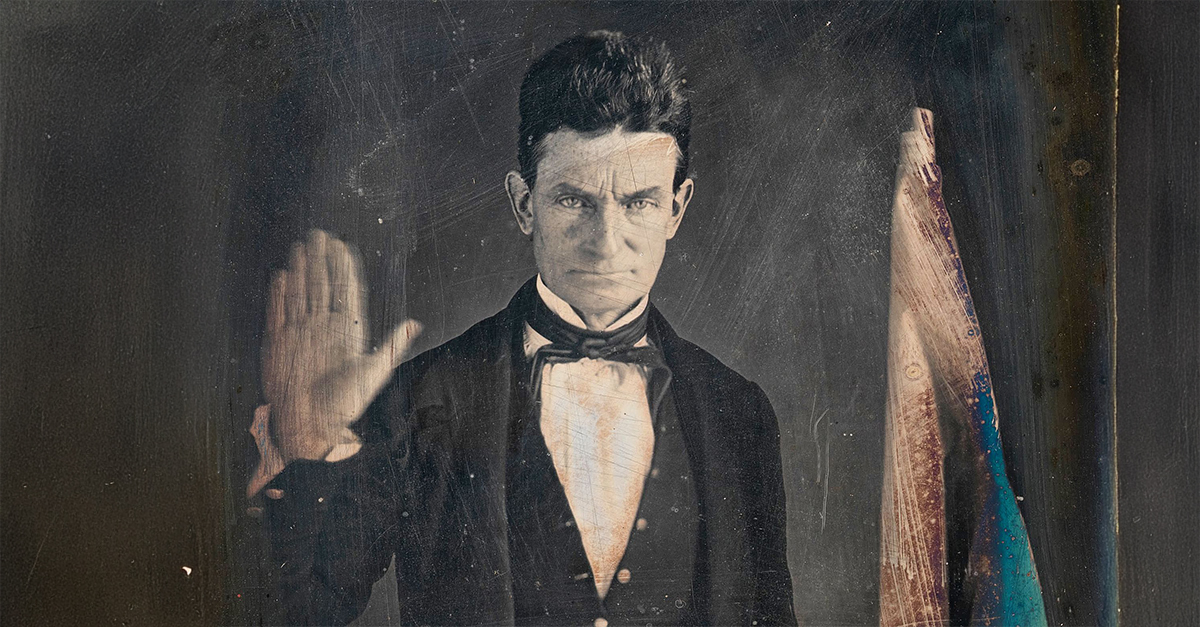

English: NPGallery, Wikimedia Commons

English: NPGallery, Wikimedia Commons

A Jury Ruled In Scott’s Favor

In the retrial in 1850, Scott was able to provide legal proof to a Missouri jury, whose members now ruled that Scott was free. This decision conformed to decades of precedent supporting freedom claims based on residence in free territories, and it briefly gave legal liberty to Scott and his family.

Tyler Vigen, Wikimedia Commons

Tyler Vigen, Wikimedia Commons

Missouri Supreme Court Reversal

Meanwhile Irene Emerson wasn’t taking things lying down. She appealed the 1850 jury verdict. In 1852, Missouri’s Supreme Court overturned the jury’s ruling. The court argued that the political conditions had changed, creating a climate of hostility against slavery that meant that slave states no longer had to abide by the laws of free states. The earlier precedents were struck down and Scott’s status went back to that of slave.

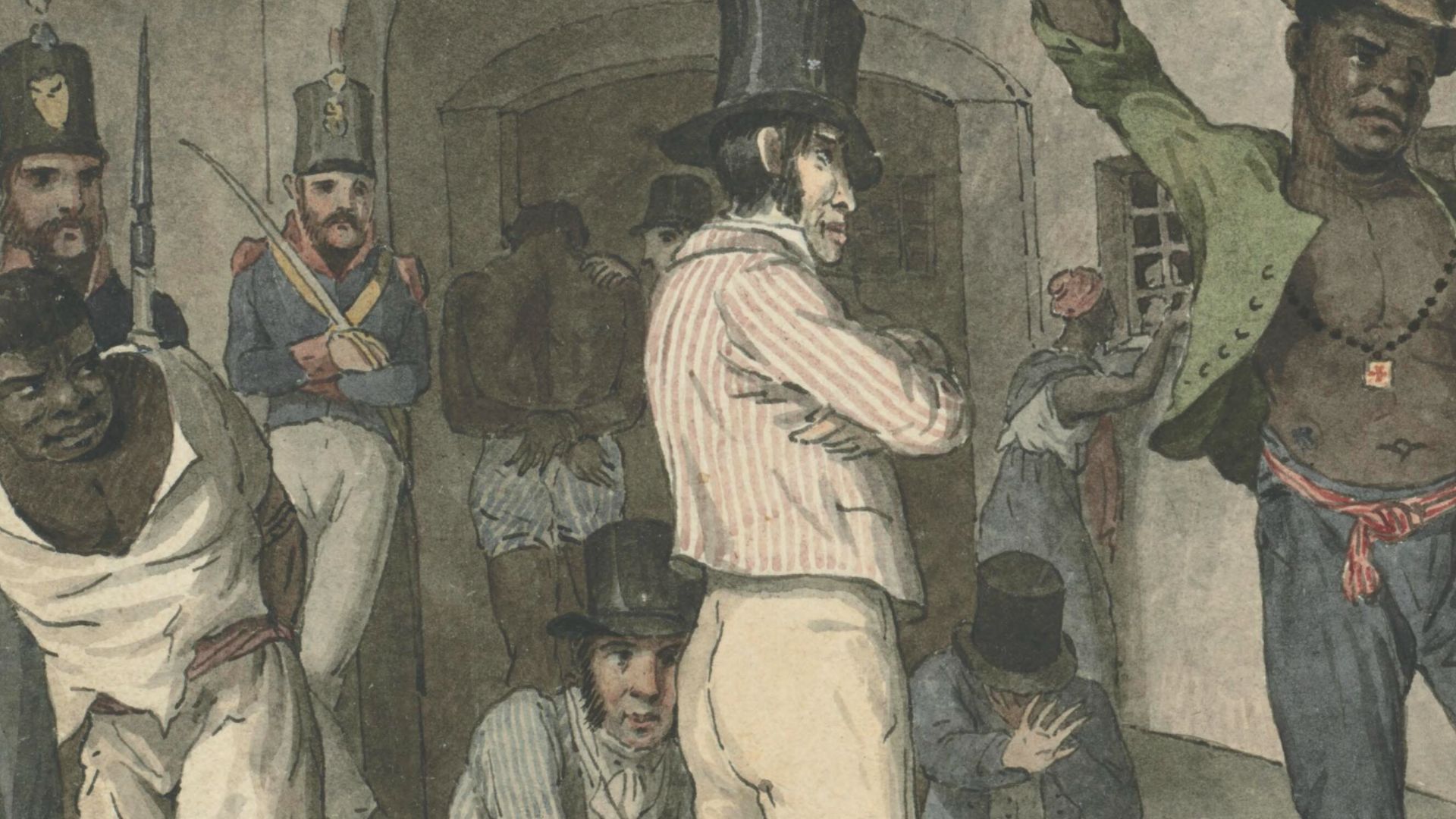

Slavery In So-Called Free States

Some states prohibited slavery altogether, but even with such laws as these, enslaved people were often held temporarily within their borders. Federal territories also banned slavery in theory without enforcing those laws in practice, a contradiction central to Scott’s case.

Augustus Earle, Wikimedia Commons

Augustus Earle, Wikimedia Commons

Shift To Federal Court

Following his reversal in Missouri state court, Scott’s case moved to Federal court. This was because Irene Emerson had sold the Scotts to her brother, John Sanford. Since Sanford was a resident of New York and Scott a resident of Missouri, the Federal court system now had jurisdiction over the case under diversity laws. This shift raised the legal stakes immensely. It was no longer just Scott’s personal freedom on the line, but slavery itself.

Supreme Court Case

Scott lost his case in federal district court, but turned around and appealed once more. By 1856, Scott’s lawsuit had arrived on the United States Supreme Court as Dred Scott v. Sanford. The Court soon broadened the case to address constitutional questions regarding citizenship and congressional authority. By now it was clear to all that the scope of the case had gone far beyond what the pro-slavery states had anticipated.

McGhiever, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

McGhiever, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Arguments Before The Court

Scott’s attorneys argued that his residence on free soil voided enslavement under the original doctrine of “once free, always free.” Opposing counsel objected bitterly that Scott lacked any standing whatever to sue. This now forced the Court’s hand. The Court now had to decide whether Black Americans could even be citizens.

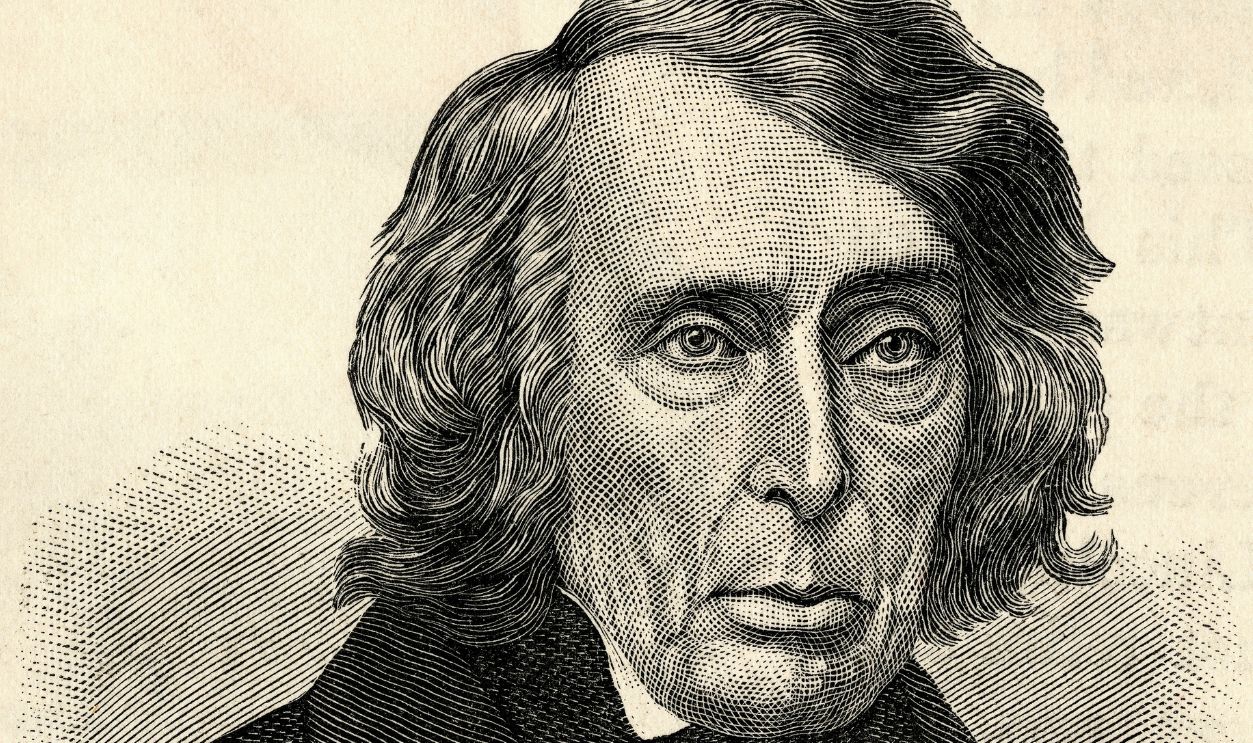

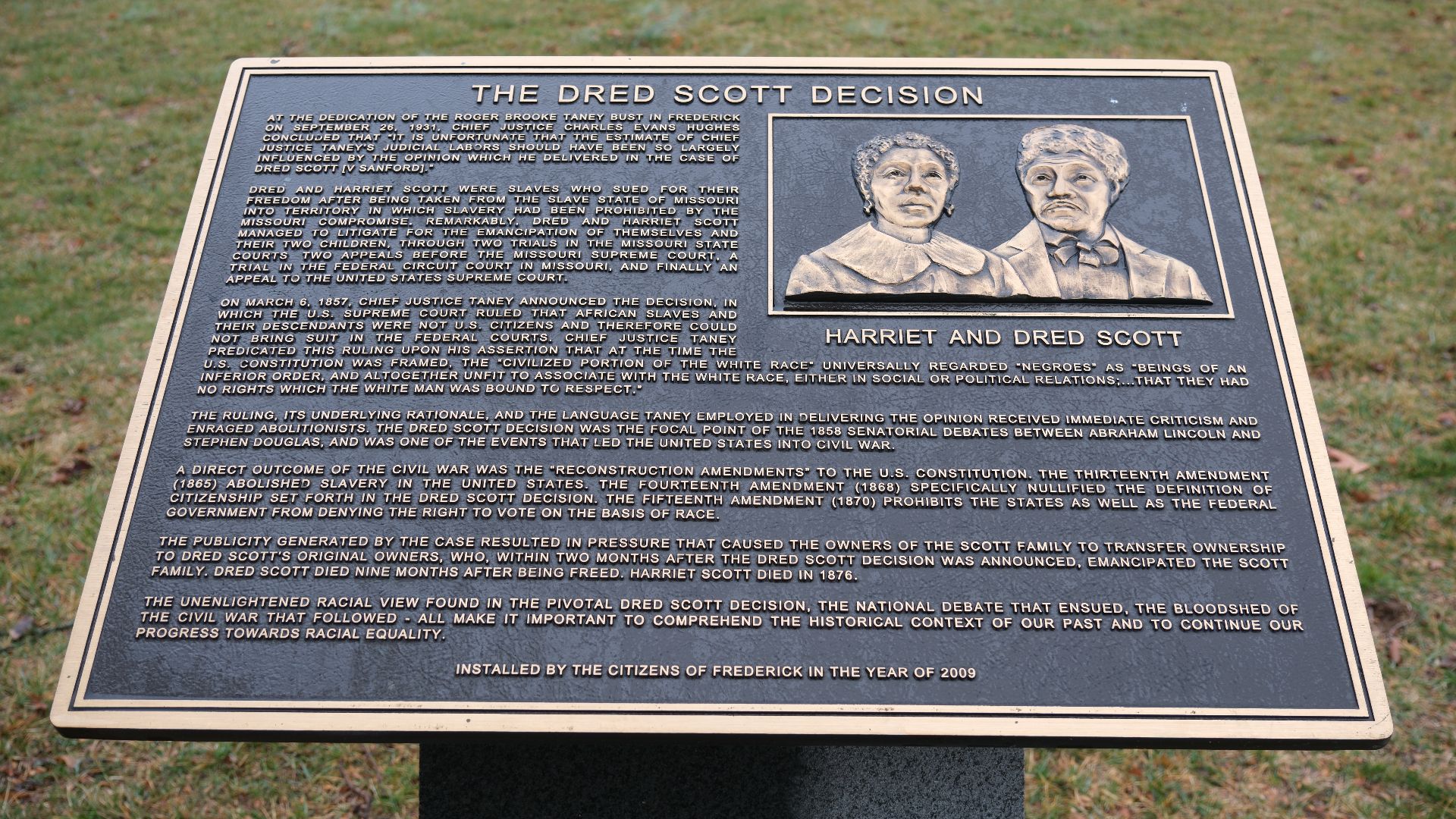

A Devastating Decision

In 1857, the Court at last ruled against Scott, declaring that African Americans were not citizens and that Congress lacked the power to ban slavery in federal territories. The verdict written by Chief Justice Roger Taney made this ruling historically sweeping. Scott’s dim but hopeful prospects of freedom had been snuffed out.

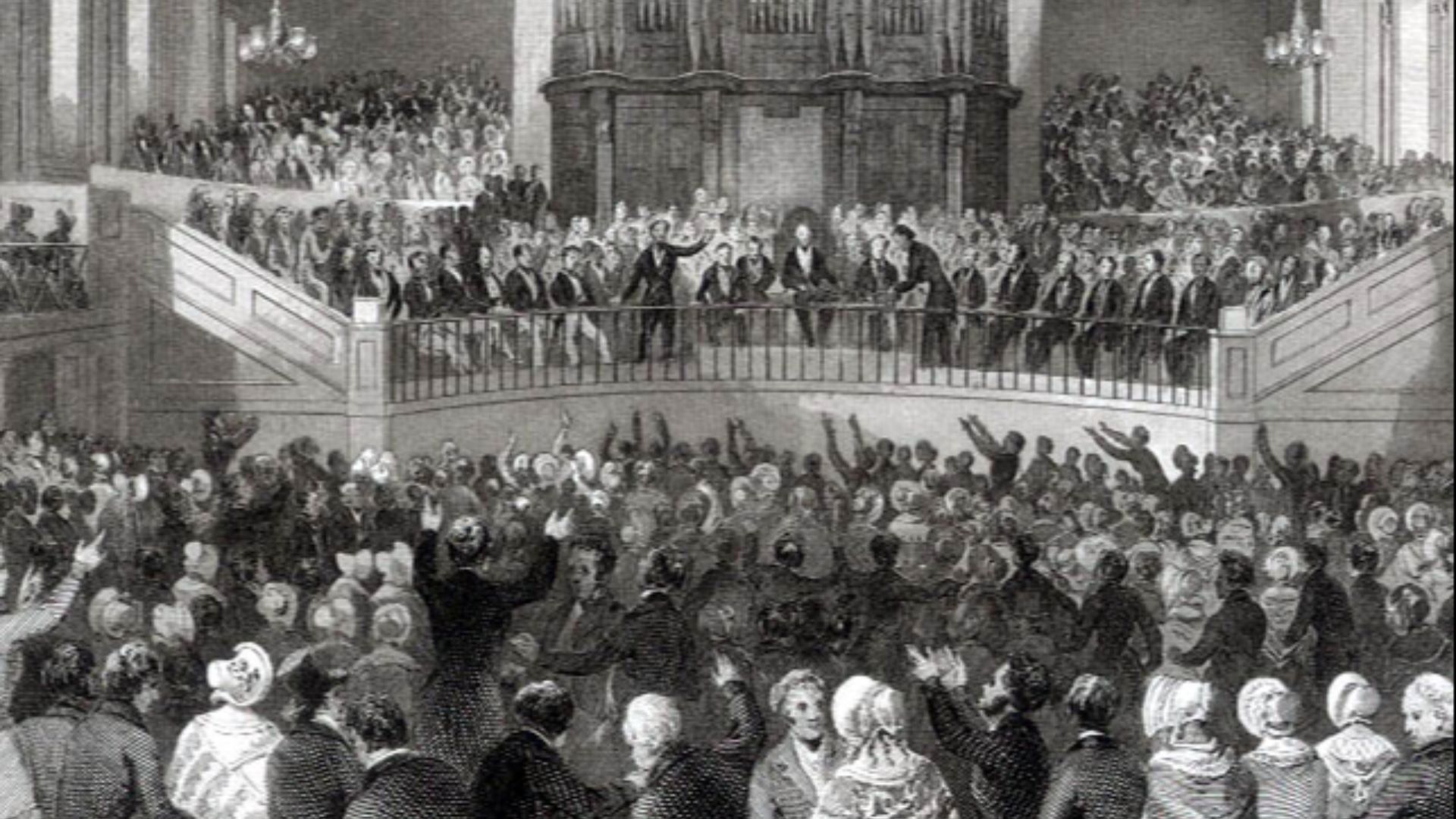

Immediate National Reaction

The decision intensified the growing tensions between the states and outraged abolitionists. Though Scott remained enslaved under the legal terms of the ruling, the case energized the rapidly spreading political movements that would soon fracture the nation in two.

Benjamin Haydon, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Haydon, Wikimedia Commons

Transfer Of Ownership

Soon after the ruling, ownership of Scott passed to the Blow family, who had owned Scott 30 years before. The Blow family's views on slavery had changed in the intervening years. The family now opposed slavery. This transfer allowed Scott to be freed privately, outside the judicial system.

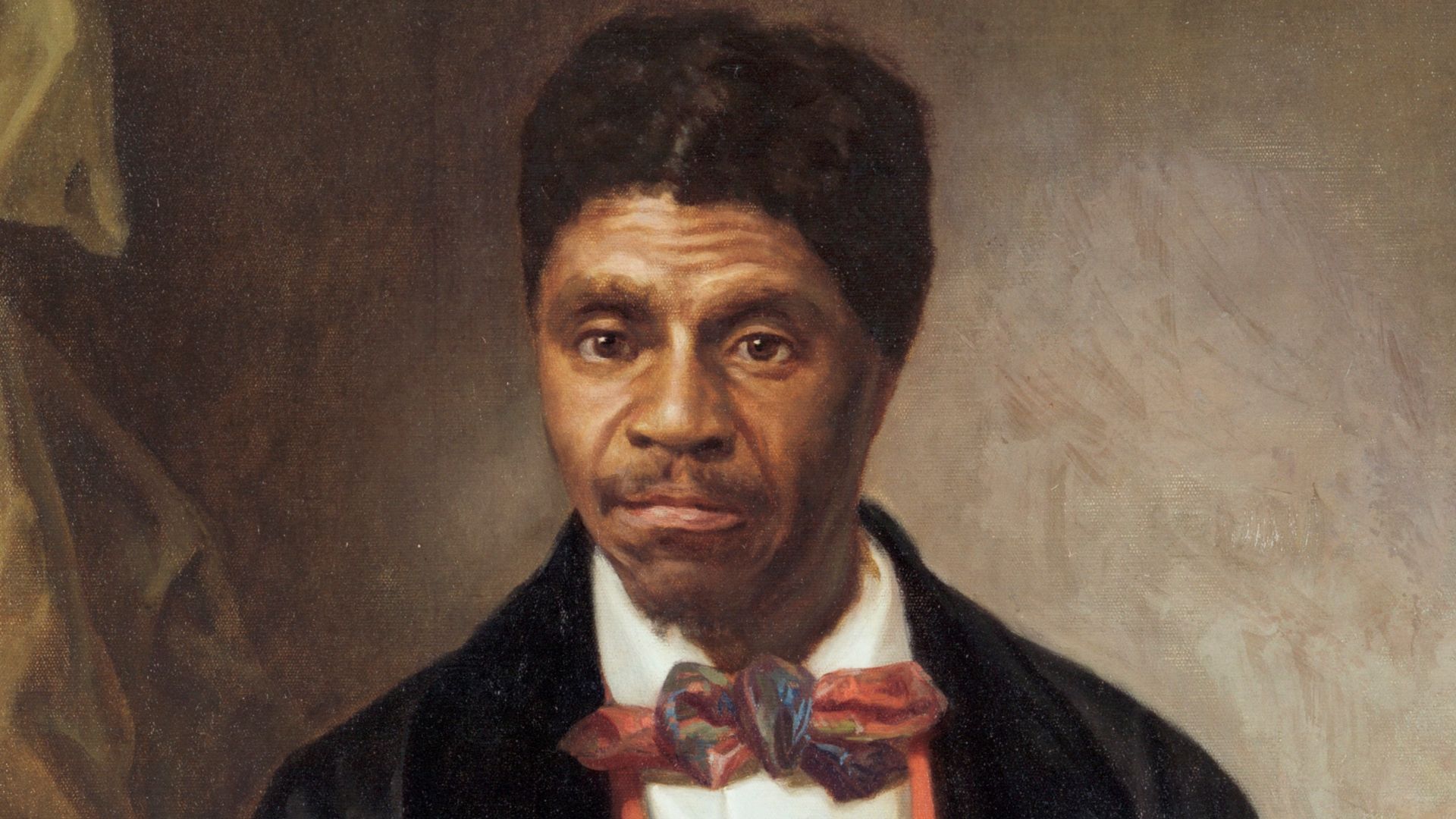

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

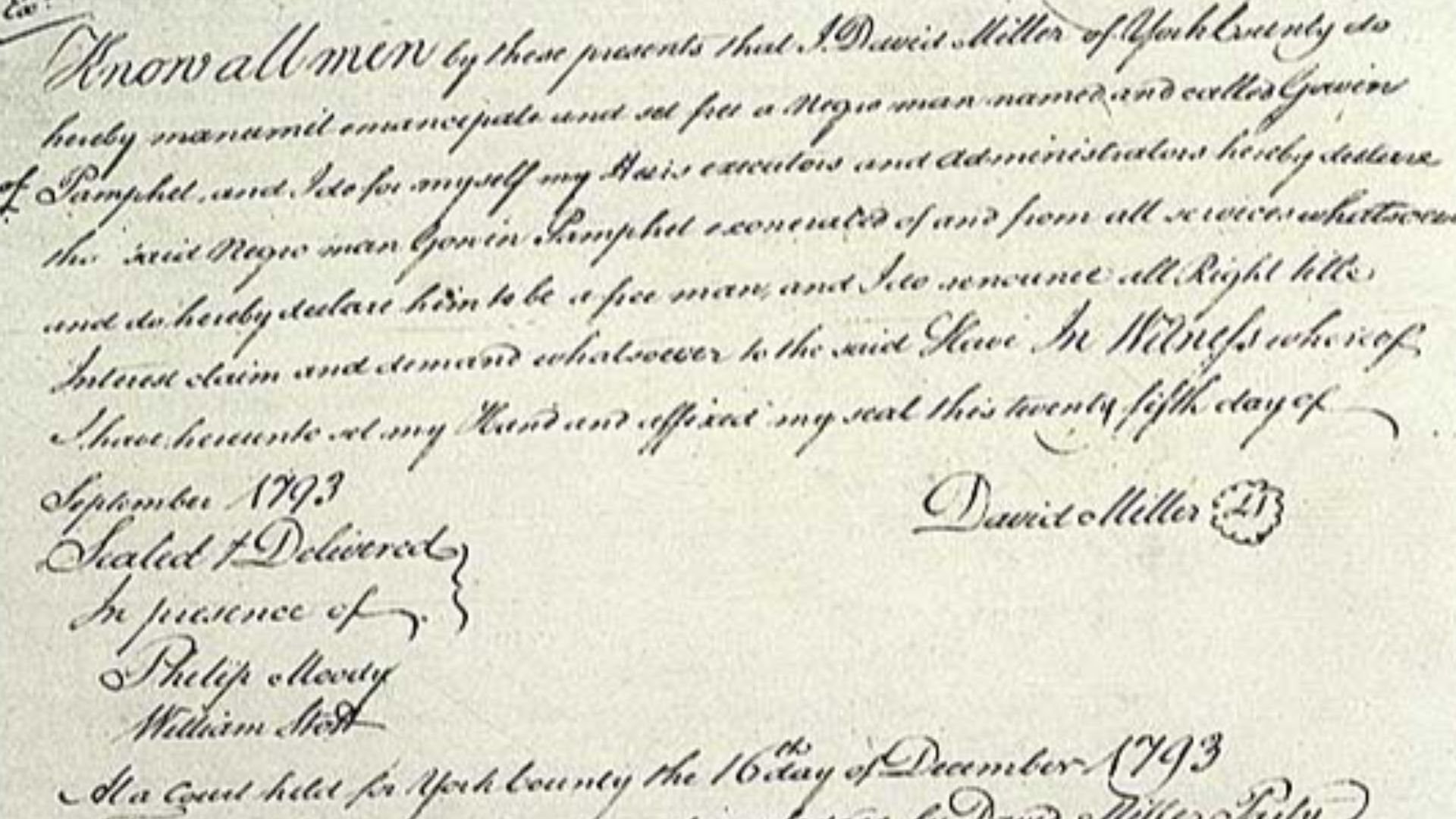

Manumission At Last

In 1857, Dred Scott and his family were formally emancipated. After decades of enslavement and more than ten years bogged down in litigation, Scott finally became a free man through the Blows’ act of manumission. With this chapter of his life over, Scott went back to work, but this time as a paid employee.

York County Register of Deeds Office, Wikimedia Commons

York County Register of Deeds Office, Wikimedia Commons

Life As A Free Worker

Following his emancipation, Scott found work as a porter at a hotel in St. Louis. His newfound freedom didn’t bring him much more than slavery did in terms of economic opportunities, though he did turn down a $1,000 offer to do a speaking tour of the North. He was happy to be done with the trial and finally working on his own terms after a lifetime of forced labor.

Engineerchange, Wikimedia Commons

Engineerchange, Wikimedia Commons

Rapid Health Decline

Scott’s health went downhill quickly. The most likely culprit was tuberculosis. Medical options in those days were limited, and his condition steadily worsened within a year of him gaining his freedom.

Photo Credit: Janice Carr Content Providers(s): CDC/ Dr. Ray Butler; Janice Carr , Wikimedia Commons

Photo Credit: Janice Carr Content Providers(s): CDC/ Dr. Ray Butler; Janice Carr , Wikimedia Commons

Death In St. Louis

Dred Scott was finally felled by tuberculosis in September 1858 at the age of approximately fifty-nine. He never lived to see the Civil War or the abolition of slavery in America. His quiet burial marked the somber end of a life that had dramatically reshaped American history. The New York Times published an obituary lamenting the passing of “this black champion.”

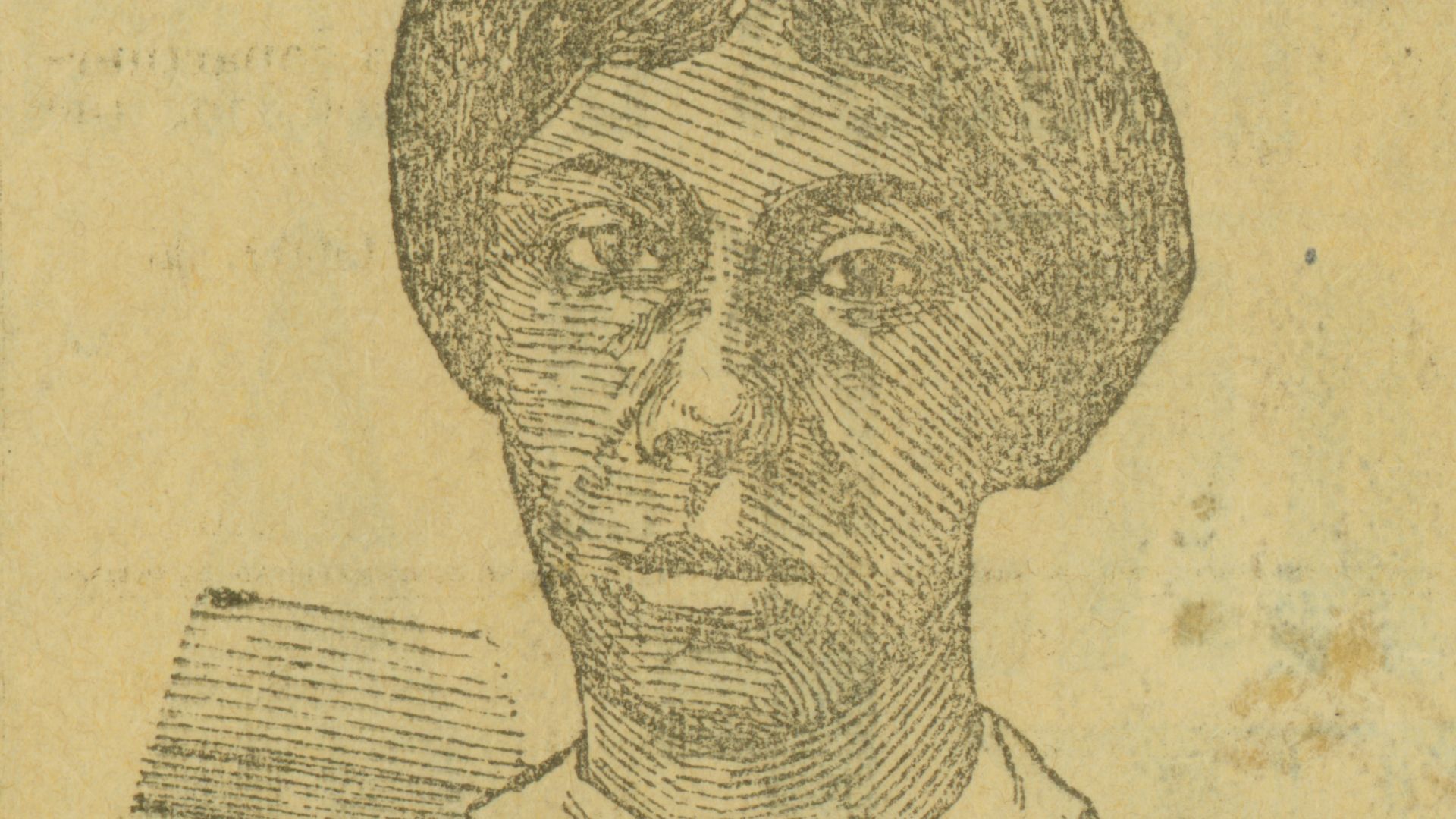

Harriet Scott’s Later Years

Harriet Robinson Scott outlived her husband and reportedly worked as a washerwoman. She remained free after her emancipation, and raised their two daughters. She lived through the Civil War and emancipation, before passing on in 1876. Her role in the legal fight is often overlooked but was essential to the family’s survival.

From a photograph by Fitzgibbon, St. Louis, Wikimedia Commons

From a photograph by Fitzgibbon, St. Louis, Wikimedia Commons

A Legacy That Lives On

Scott’s daughters lived on, eventually married, and raised families of their own. While Scott never received compensation, (in fact Irene Emerson collected Dred and Harriet’s wages after the trial was over) his name became permanently etched in one of the most devastating Supreme Court decisions in American history. A bronze statue of Dred and Harriet Scott now stands in front of the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis.

St. Louis Daily Globe, Wikimedia Commons

St. Louis Daily Globe, Wikimedia Commons

He Exposed The Law’s Insanity

The facts of Dred Scott’s life moving from state to state showed everyone how enslavement really operated across borders and legal systems. His case is to this day one of the clearest demonstrations of how the law can utterly fail to uphold the cause of human freedom.

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, NPS, Wikimedia Commons

Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, NPS, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

Liberating Facts About Harriet Tubman, The American Emancipator

Honorable Facts About Abraham Lincoln, America’s Most Tragic President