From The Congo To The Bronx

Starting in Africa in the 19th century, Ota Benga ended his life decades later on the other side of the world, and his journey from the Congo Free State to a Bronx Zoo was an inverted American Dream perverted with all the evils of humanity.

Nonetheless, right up until his tragic fate, Benga found ways to defy everyone.

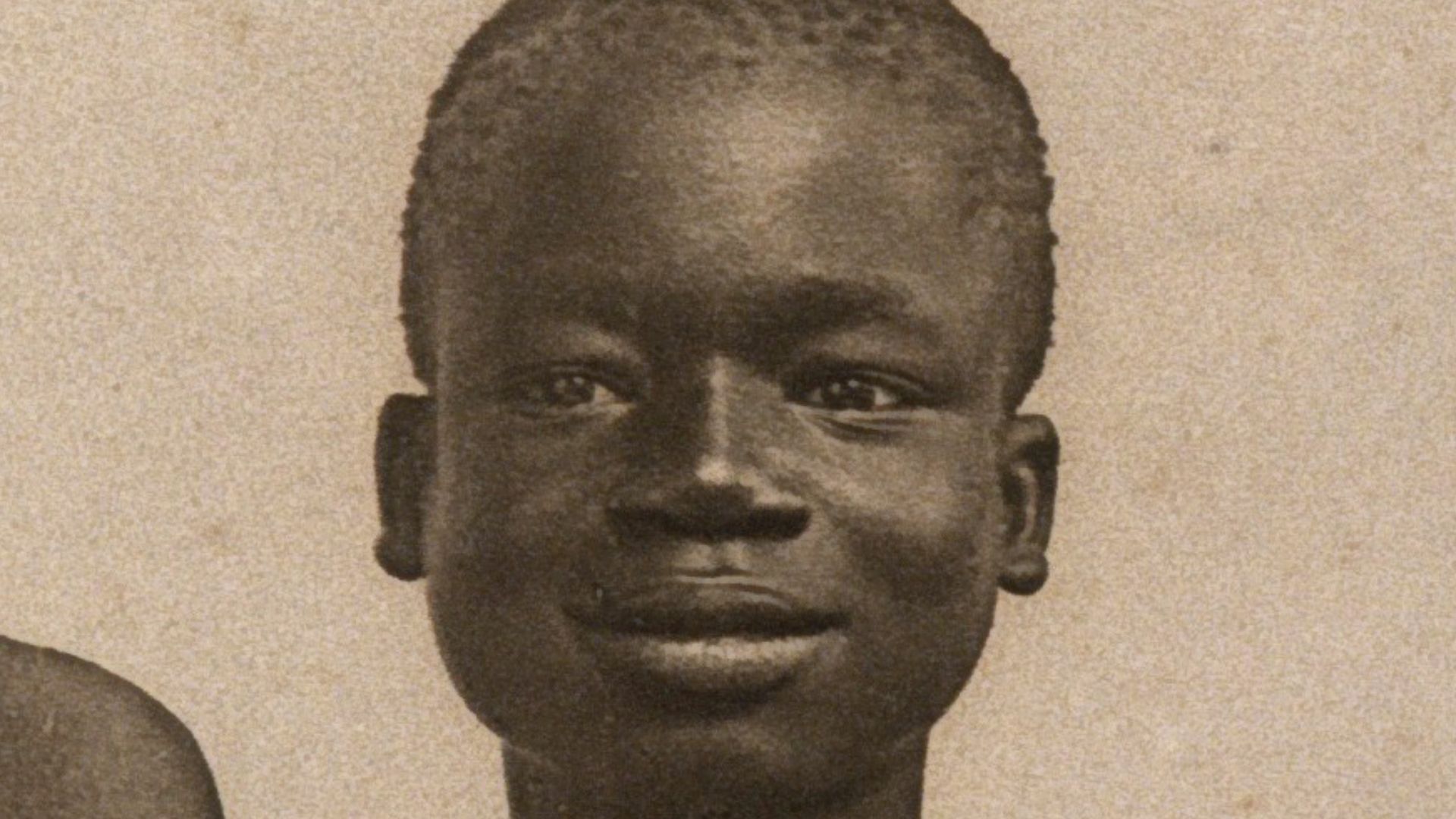

1. He Was Born In A Bad Time

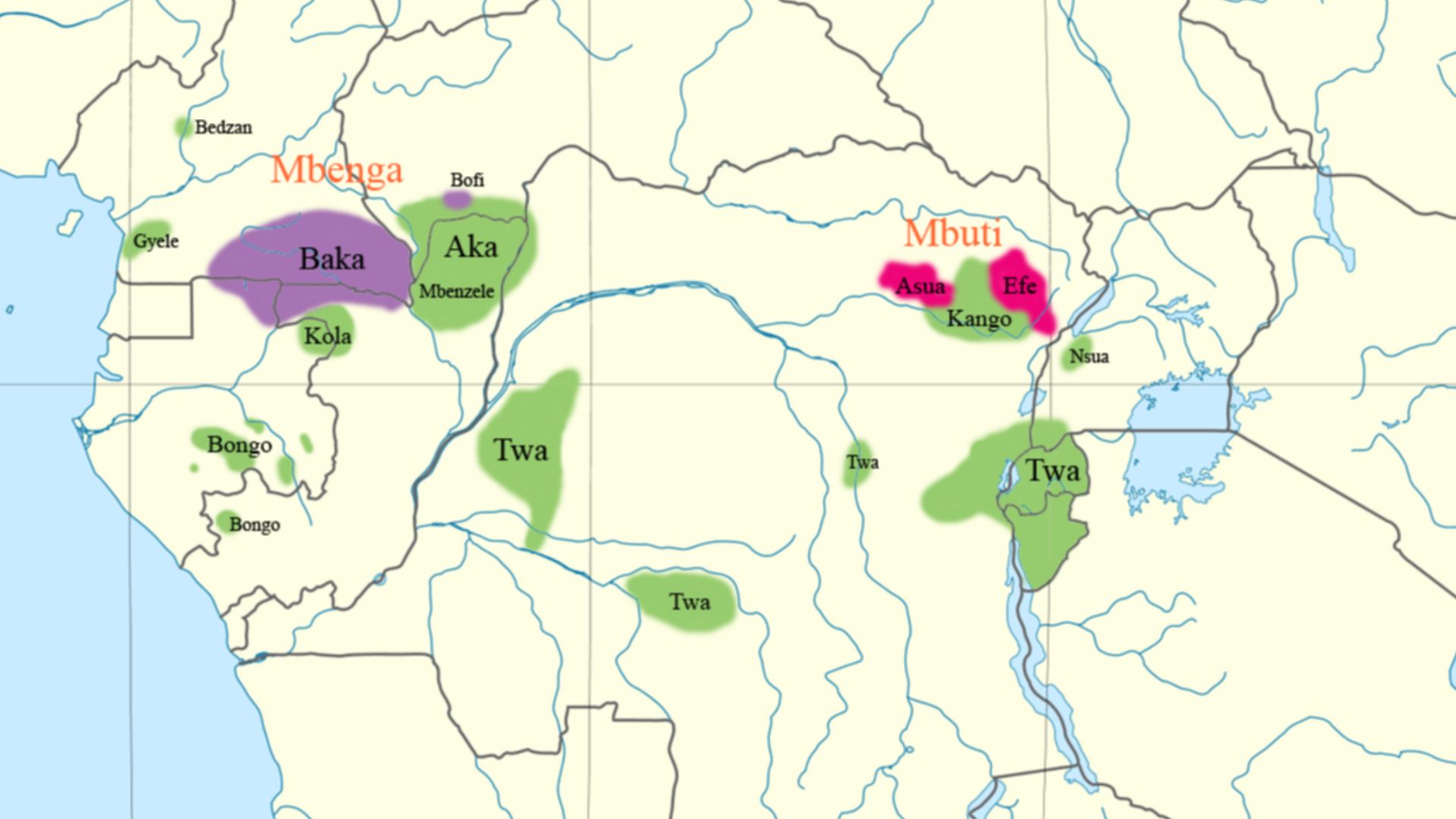

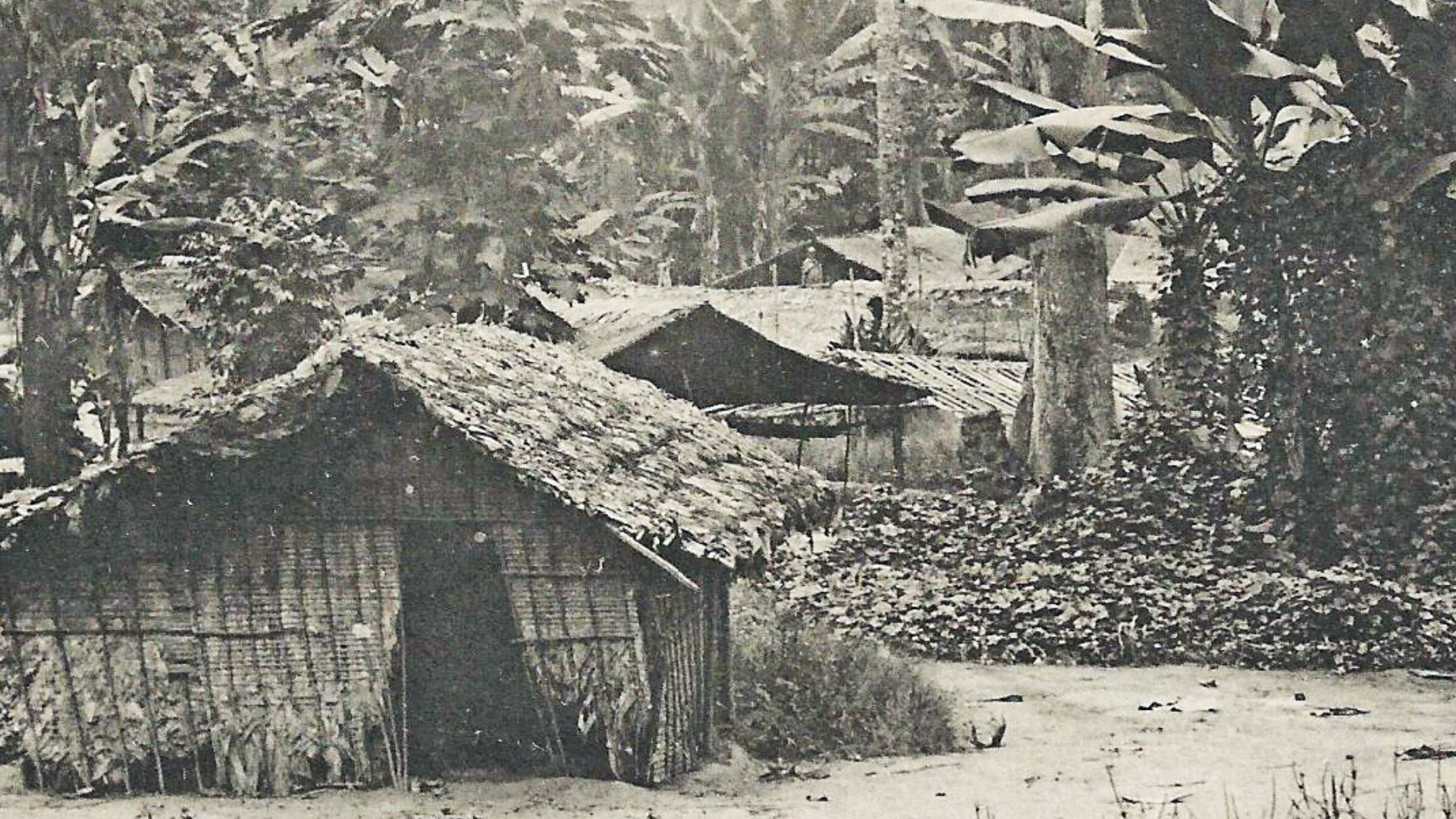

Born around 1883, Ota Benga came into the world during his country’s most brutal hour. A member of the forest-dwelling Mbuti people, Benga and his family lived in what was then the Congo Free State, where King Leopold II of Belgium was currently ravaging the land and tormenting its people in pursuit of rubber manufacturing and its attendant fortunes.

Eventually, these horrors came right to Benga’s door.

Alexander Bassano, Wikimedia Commons

Alexander Bassano, Wikimedia Commons

2. He Lost His Family Brutally

When he was still a young adult, Benga experienced a true nightmare. King Leopold’s militia, hungry for more land and people to exploit, attacked Benga’s people, killing his wife and two children in the process. Although Benga survived, it was a matter of pure luck: He’d been out hunting when the men appeared.

Whatever luck he had, however, was about to completely run out.

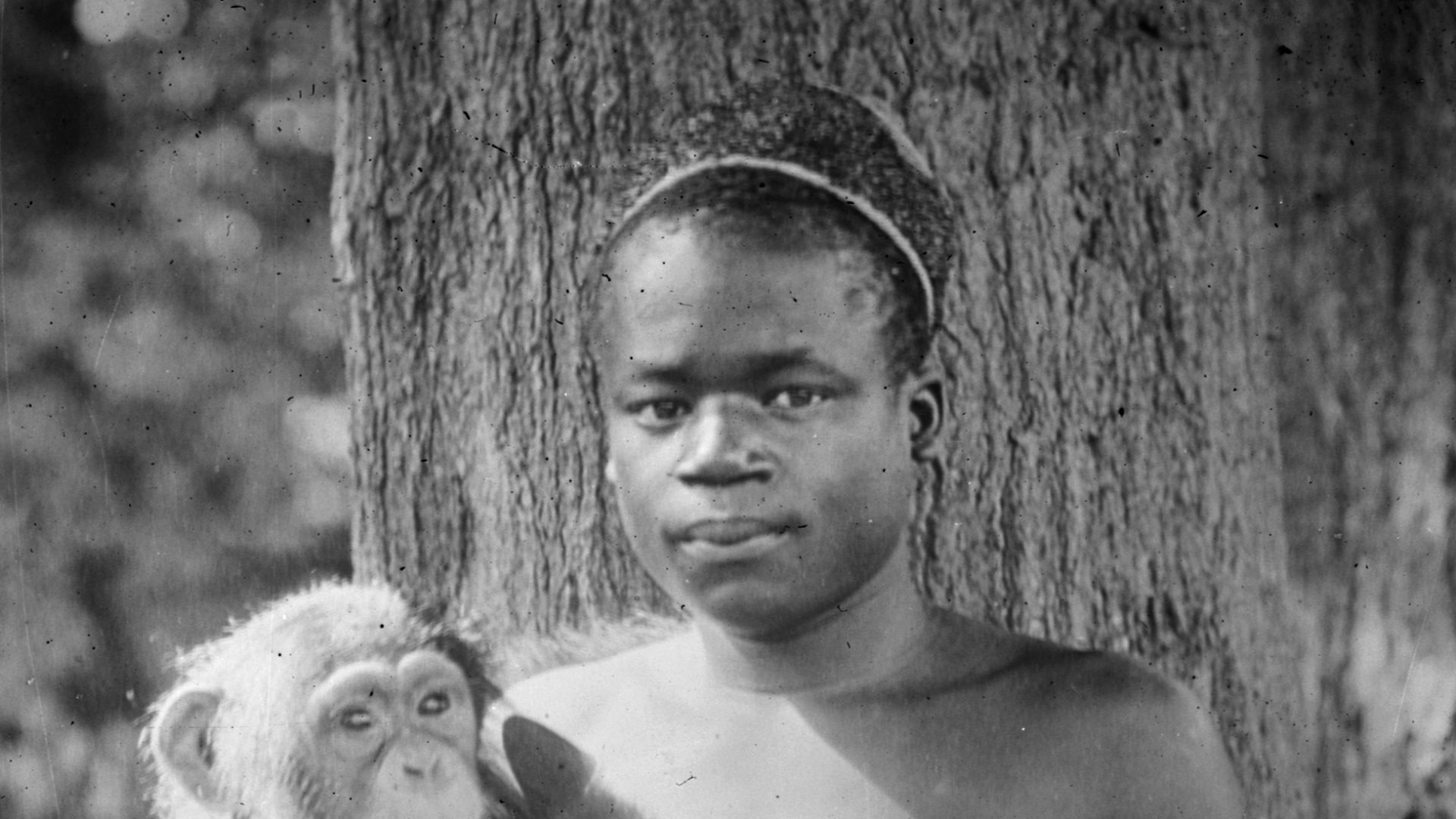

Gerhard Sisters, Wikimedia Commons

Gerhard Sisters, Wikimedia Commons

3. He Was Tiny

As a Mbuti, Benga was part of Africa’s “pygmy” ethnic group, meaning that he and most of his people were of smaller stature; Benga was just under 5 feet tall in adulthood. Although he was a fierce and skilled hunter, this physical trait could also make him vulnerable to enemies. Enemies who were just around the corner.

Kwamikagami, Wikimedia Commons

Kwamikagami, Wikimedia Commons

4. He Got Kidnapped

Soon after he lost his family, Benga’s life went through another brutal upheaval. Members of the enemy Bashilele tribe kidnapped him and put him into their slave trade. Benga had lost practically everyone he loved, and now he had lost his freedom.

When his “savior” came, even this was a double-edged sword.

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

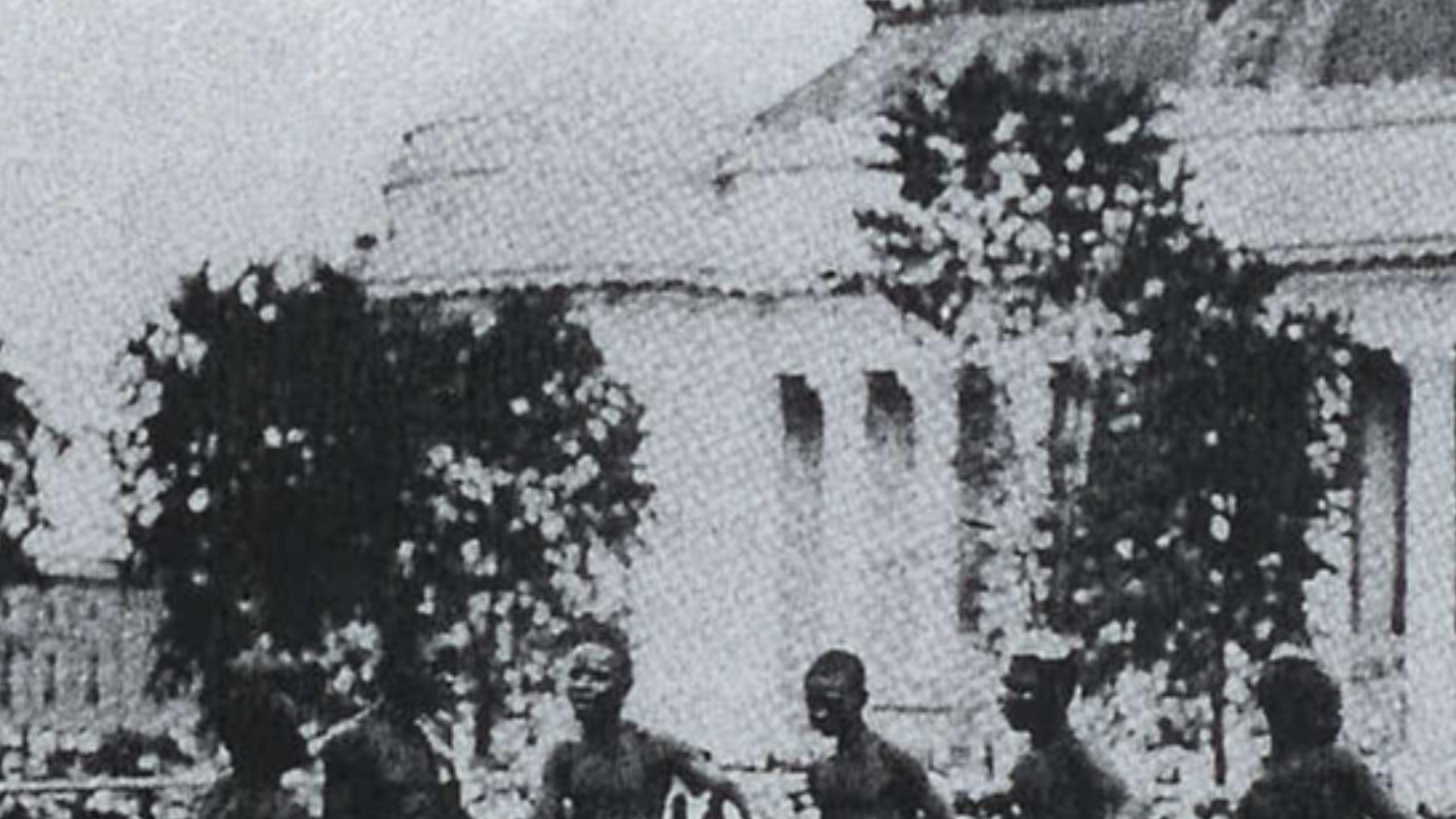

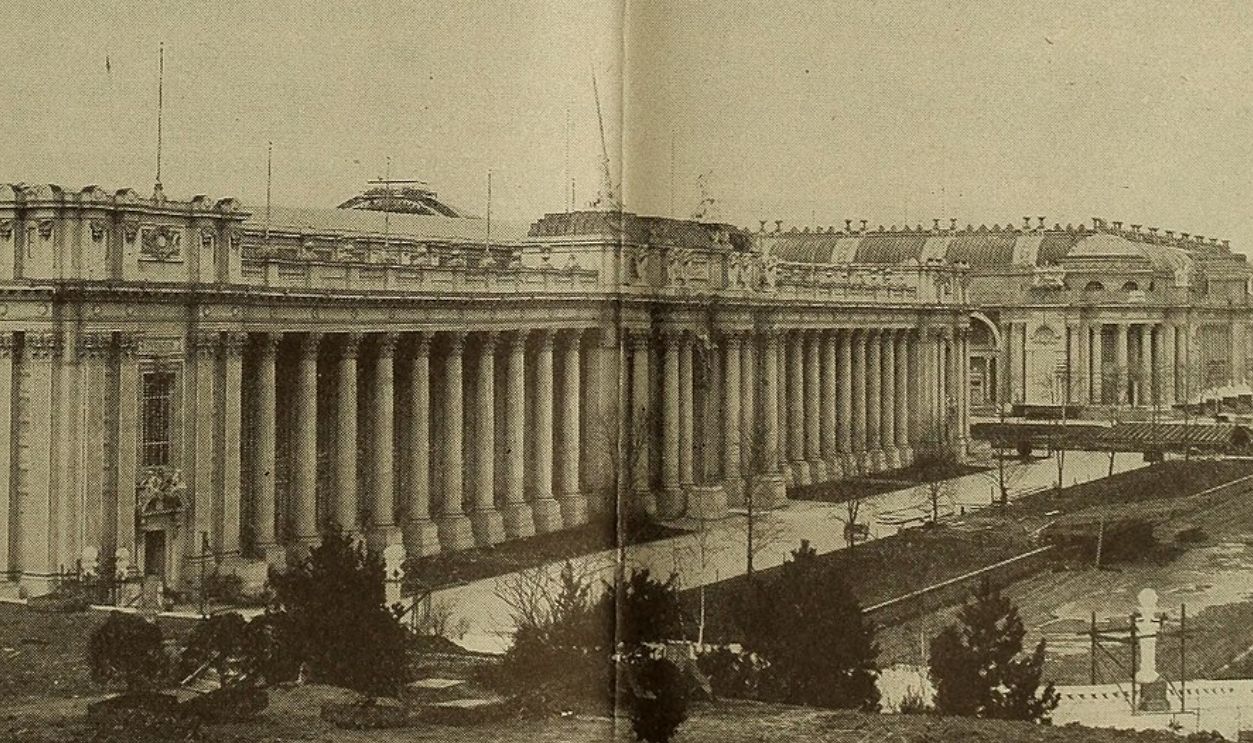

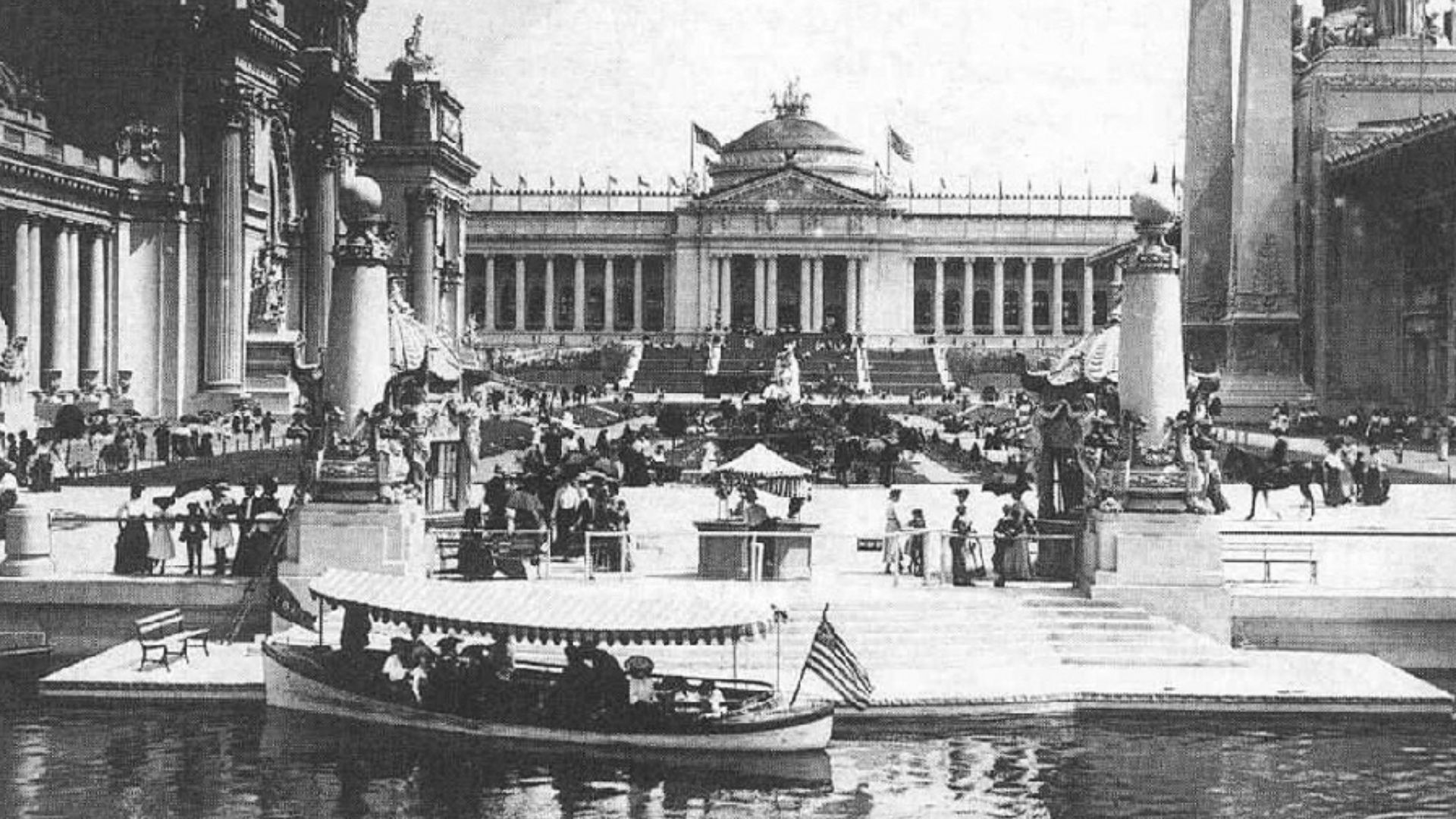

5. An American “Discovered” Him

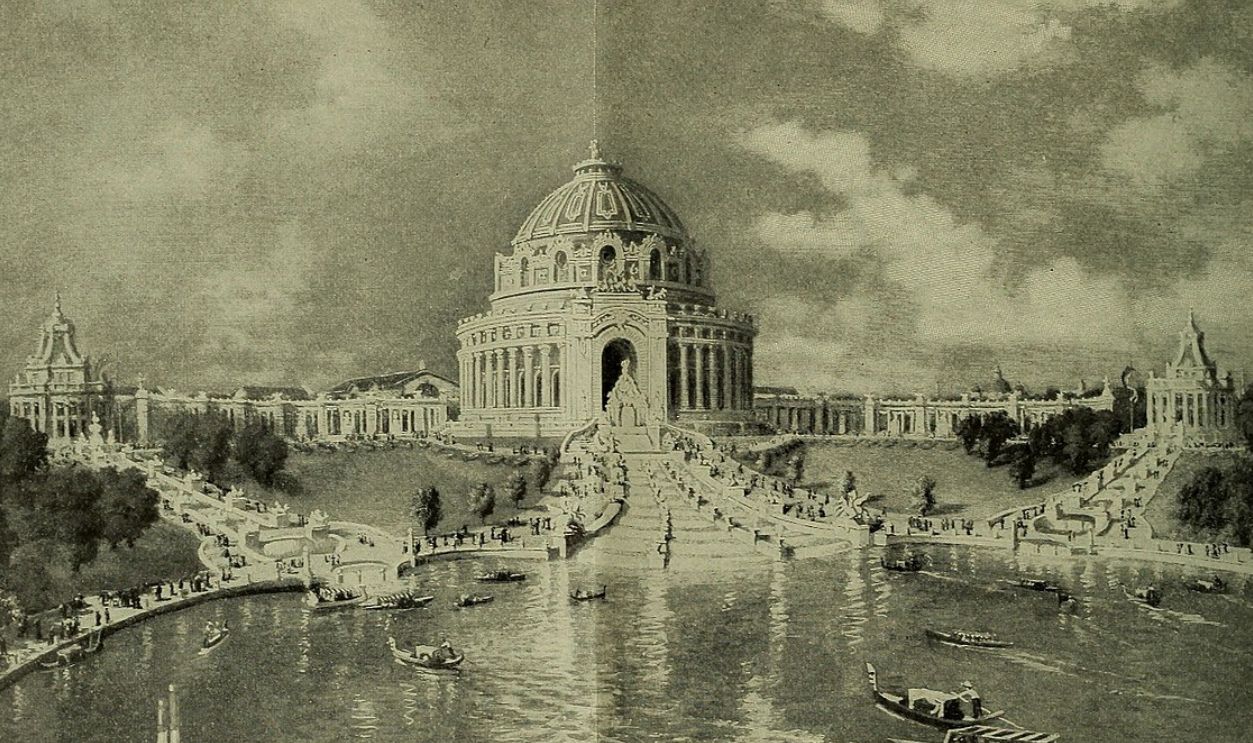

In 1904, the so-called “African explorer” Samuel Phillips Verner came into Africa with a very specific purpose. With the enthusiastic agreement of King Leopold II, he was to find several pygmies, including “one patriarch or chief” as well as “one adult woman” and “four more pygmies” for the upcoming Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St Louis, Missouri.

So when Verner just happened to enter the village where Benga was, his eyes went wide.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

6. He Was Supposedly Ready And Willing

According to one of Verner’s earliest explanations, after buying Benga from the Bashilele with a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth, he approached the young man and told him about the Expo. Benga was reportedly “delighted to come with us, for he was many miles from his people, and the Bashilele were not easy masters”. But Verner’s supposed charity didn’t end there.

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

7. His “Savoir” Made Dark Claims

Verner’s first interaction with Benga was also tainted with a more dire accusation. Verner would later claim that the people Benga had been with had practiced cannibalism, and that part of his rush to extricate Benga was to save him from this vicious fate. If that sounds like pure drama, it’s because it likely was. Instead, the truth was bleak.

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

8. He Had Ulterior Motives

The details of the story changed constantly over the years, but Verner always seemed to leave out one crucial thing. Some have pointed out that the Bassongo area where Verner found Benga was a very well-known slave market, and that far from accidentally stumbling on the spot, Verner may have gone there with the express purpose of finding a slave to bring home.

Still, Benga’s reaction to all this confused even his countrymen.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

9. He Stood By Him

Benga may have been suspicious of Verner’s intentions, but he did willingly follow him from this point on, accompanying the American as he continued his quest to “collect” a full complement of African pygmies for the Expo. The next stop: The somewhat nearby Batwa village. But when they arrived several weeks later, they got a nasty surprise.

10. His People Were Suspicious

By now, King Leopold’s atrocities were well known to many of the Congolese, and they didn’t trust this white man as far as they could throw him, even with Ota Benga beside him. Indeed, even Verner admitted that the Batwa were “violently opposed” to his suggestions that they come to America, with some women even crying throughout the night at the thought.

Eventually though, Verner was terrifyingly successful.

11. He Went On A Campaign

Through murky methods he claimed were all above-board, Verner (who was armed at the time) apparently managed to “convince” 20 men and boys to come with them. Despite this, when the time came to board the steamer, half of them somehow didn’t show up, having—according to Verner—had given “way to their fears”.

Yet Benga’s role in all this wasn’t miniscule, either.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

12. He Turned On The Charm

Benga appears to have played a part in helping convince the countrymen who did show up that day to trust and go with Verner. He told anyone who would listen how Verner had saved his life, and shared his curiosity in seeing the place that Verner had come from. He even vouched for Verner as a person, saying he was close to him.

In the end, Benga might have lived to regret this.

13. They Were Painfully Young

On May 11, 1904, Ota Benga and a small group of other young men boarded the ship that would take them to Leopoldville, where they would then go on to New Orleans. The passenger manifest that day presents a sobering truth. Some of these “young men” were merely boys: the youngest, Bomushubba, was only 12 years old, while the second youngest, Lumbaugu, was 14.

The manifest also revealed a devastating secret about Benga.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

14. He Wasn’t What He Seemed

Although Verner would later claim Benga was a full grown man at the time, the passenger list from that day states that Benga was only 17 years old when he came over to America. It’s no surprise, then, that Benga and the other young members of his group were ill-equipped to handle what came next.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

15. His Mentor Fell Ill

In truth, Benga’s arrival in America was a disaster. They were supposed to all head to St Louis from New Orleans, but by the time they landed Verner had fallen deathly ill. While some reports say it was malaria or sunstroke, one fellow passenger commented that they thought Verner was “cracked”.

While Verner eventually returned, Ota Benga was now virtually alone in a new country. He was also headed for worse.

Gerhard Sisters, Wikimedia Commons

Gerhard Sisters, Wikimedia Commons

16. Americans Loved Him

After all this wheedling and traveling, Verner and his “collection” came to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition two months late, and without any chiefs or women in tow. Not that it mattered: The American public fell over themselves to see the World’s Fair’s “African Pygmies”. One of Benga’s features in particular caught their eye.

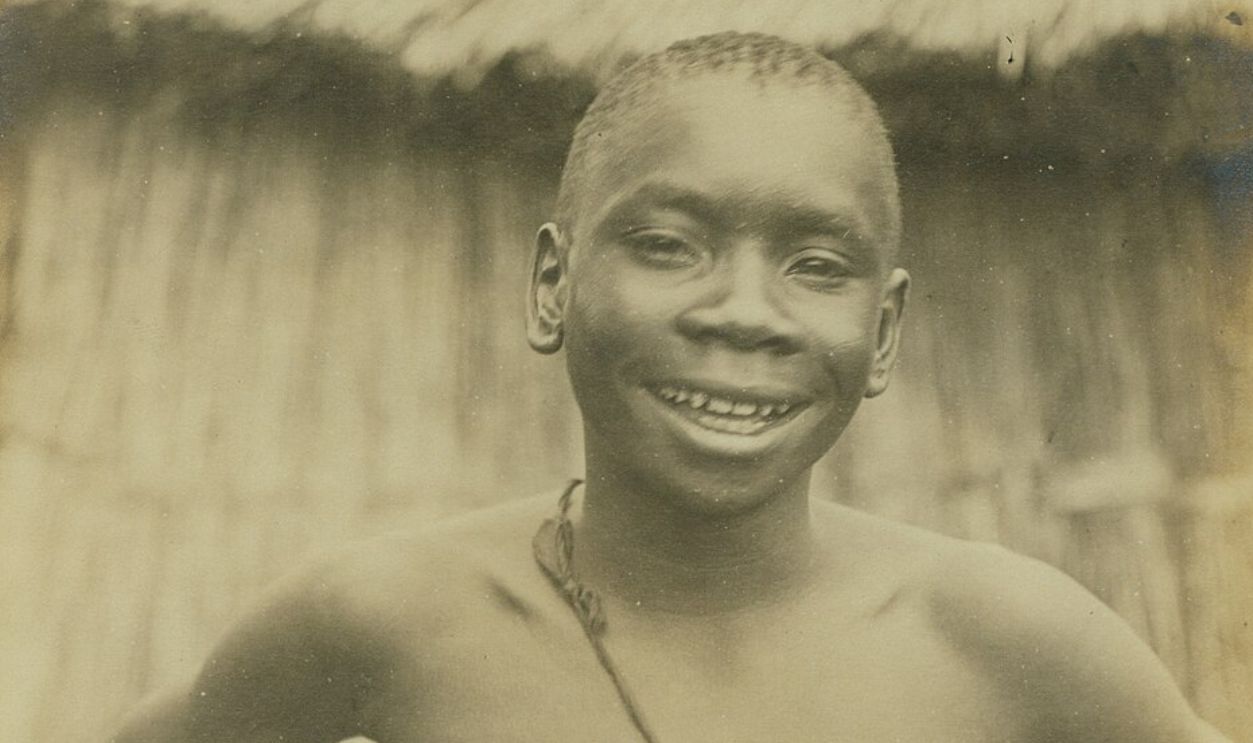

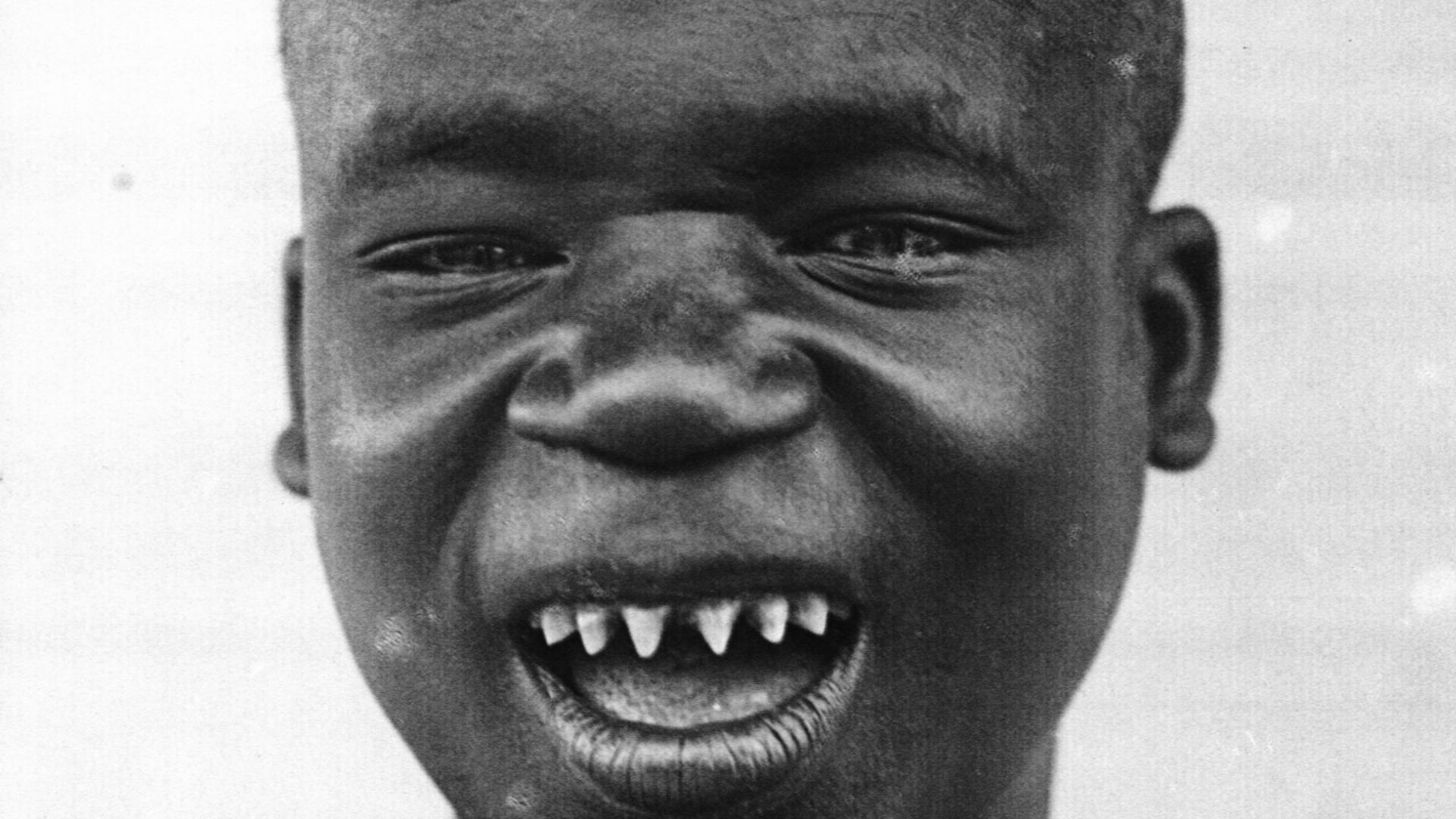

17. He Had An Unusual Trait

When Ota Benga arrived at the Expo, audiences gasped when he opened his mouth. Benga’s teeth had been filed into sharp points when he was a boy as ritual decoration, and, when combined with Benga’s easy and outgoing personality, he soon became one of the most popular “attractions” at the exhibit.

But this was no place for real kindness, and St Louis would soon make that clear.

18. The Public Turned On Him

Although Benga and the other Congolese men were initially the darlings of the Expo, it took nothing for the newspapers to turn on them, swapping their humanity for flashy headlines. One read, “Pygmies Demand a Monkey Diet: Gentlemen from South Africa at the Fair Likely to Prove Troublesome in Matter of Food”.

The crowds could turn on them, too.

19. He Couldn’t Find Peace

On Sundays, Benga and the others liked to meet in the forest for a moment of calm with each other. Yet even this was too much to ask the American crowds. Thanks to the public fascination with the Congolese, people would manage to disrupt even these quiet moments, bursting in to gape at them. They went on to do much worse.

20. They Attacked His Pets

Unheeding that these were actual humans in front of them, audiences at the Expo often pinched and poked at Benga and his friends. As if that weren’t enough, they also liked to taunt the pet parrots and monkeys the fair had set them up with, even sometimes burning the animals with cigars.

Even so, this didn’t compare to what was going on behind the scenes.

Ernst Vikne, Wikimedia Commons

Ernst Vikne, Wikimedia Commons

21. He Was Mistreated

Benga had arrived in St Louis at the height of summer, but as time went on it began to get colder and colder on the fairgrounds, especially at night. The response was enraging. In the face of this, administrators didn’t give Benga or the others proper clothing or shelter, leaving them brutally cold most of the time.

Then came the vicious rumors.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

22. They Told Lies About Him

Thanks to Benga’s filed teeth and his African origin, it didn’t take much for the American public to begin suggesting that Benga was actually a cannibal. One newspaper report went so far as to call him “the only genuine African cannibal in America”.

Yet for all his affable nature, Benga wasn’t about to let this get him down. He knew how to survive, and he began to do it in a very American way.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

23. He Was Cunning

Benga was no passive man, willing to let people gawk at him and move along. He and his fellow Congolese came up with a brilliant plan. Seeing the massive interest people took in them, they started charging for photographs and various performances. Benga reportedly even charged five cents for a glimpse of his famous teeth.

He also made some influential friends.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

24. He Played Along

Eventually, Benga and the others realized that the Americans coming to see them wanted them to behave like the “savages” they thought they were, and would probably cough up more money if they obliged. However, with no touchpoint for what that really meant, Benga and company began looking to the Expo’s Native American contingent for an example of how to act, and soon produced “warlike” motions for the crowd.

One of those Native Americans took notice.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

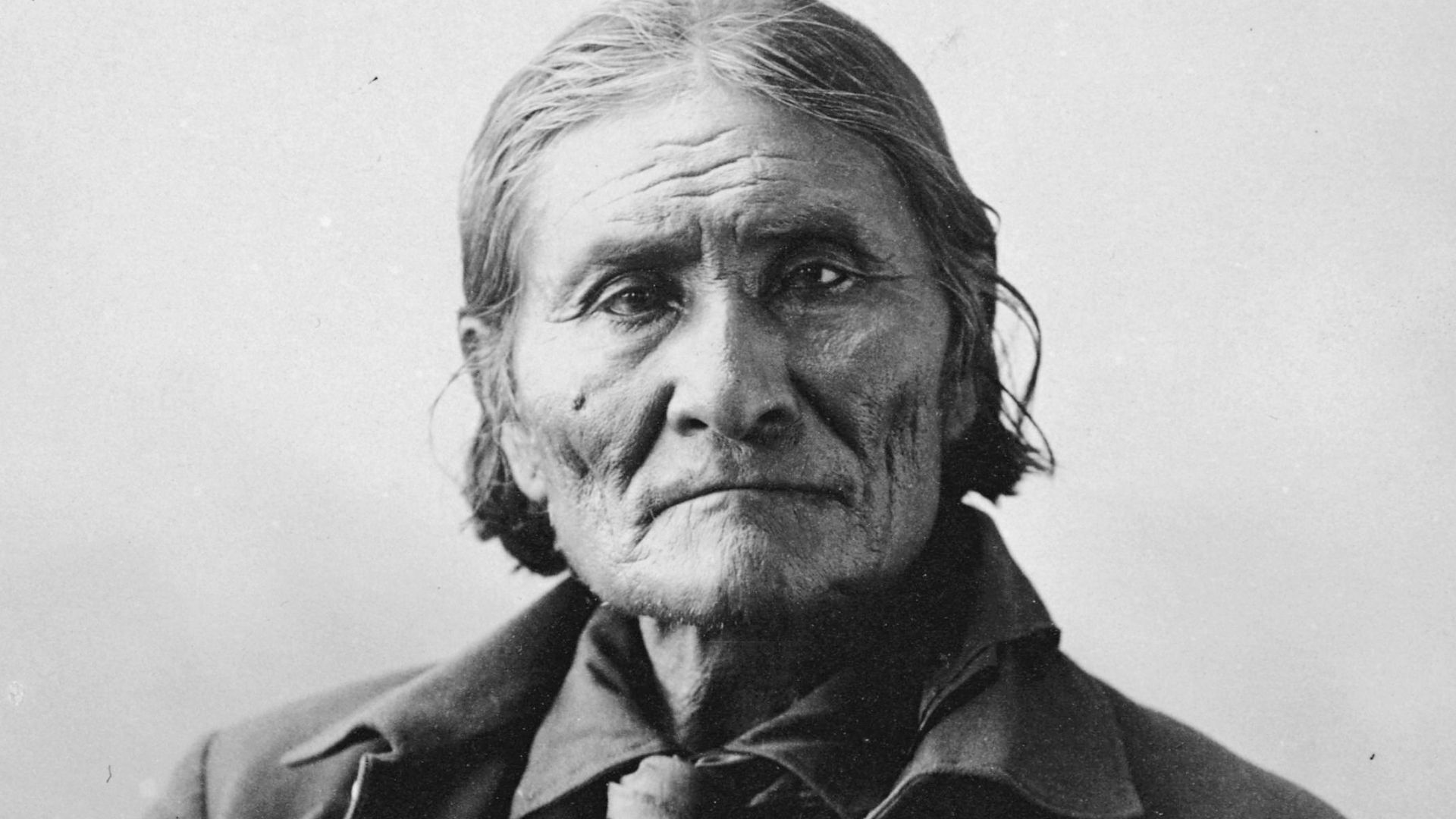

25. He Made A Famous Friend

As it happened, none other than Apache leader Geronimo, on special dispensation from the government, was also at the Expo under the name “The Human Tyger”. He, too, took a shine to Benga, and gave the Congolese man one of his arrowheads as a mark of his admiration.

When the Louisiana Purchase Exposition wrapped up, Benga made a fateful decision.

Adolph F. Muhr, Wikimedia Commons

Adolph F. Muhr, Wikimedia Commons

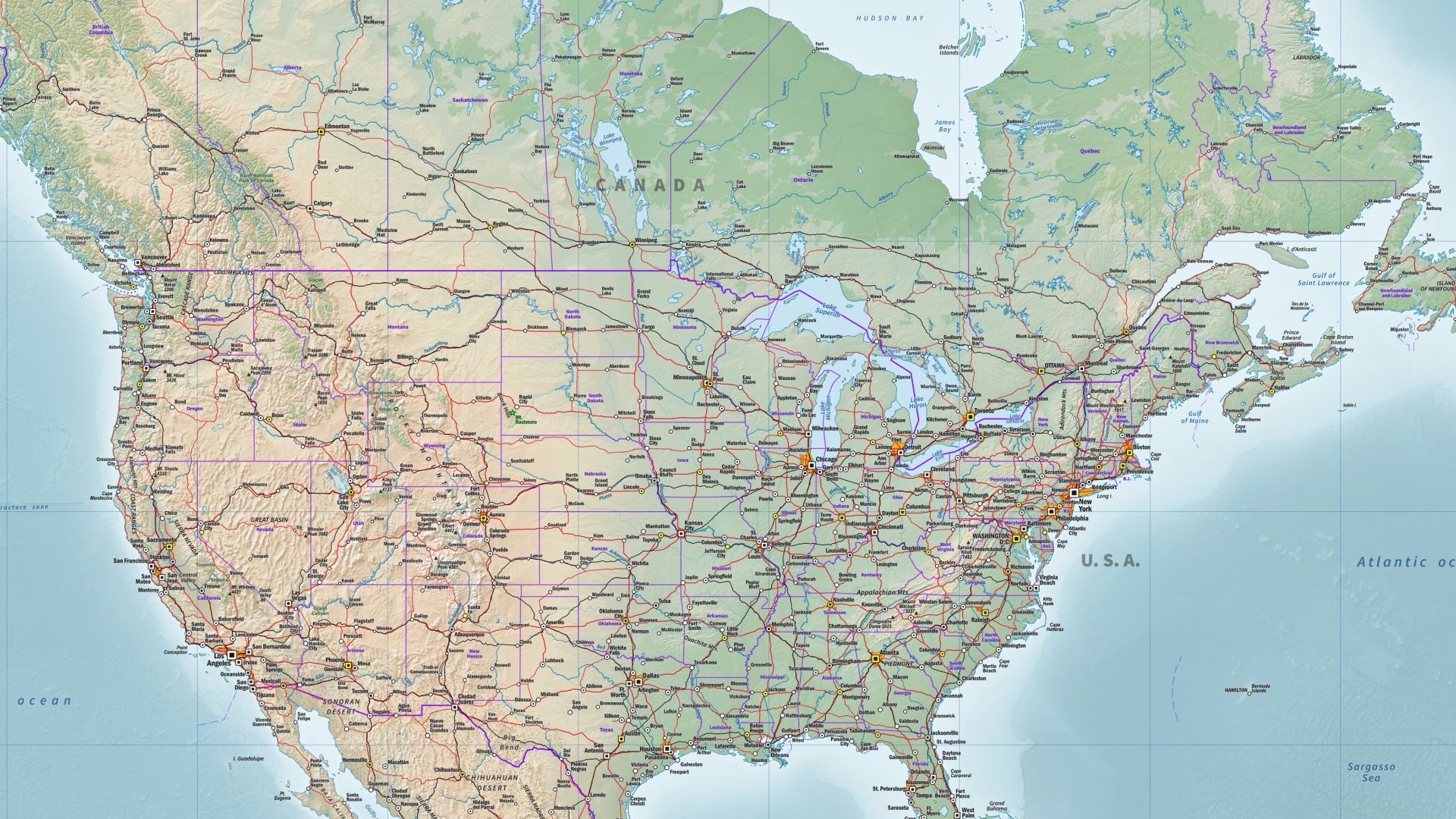

26. He Tried To Go Back Home

After the Expo, Benga decided to go back to the Congo, this time alongside Verner from the start, and think more about what his next steps might be. In the Congo, he split his time between traveling around with Verner and living a more stable life in a Batwa village—he even reportedly re-married. But for all this, Benga was about to learn a harsh lesson.

27. He Lost Everything Again

By now, Benga had become used to American ways, and during this time he never seemed to be able to put down roots in his birthplace or feel completely comfortable with the Batwa. Then the other shoe dropped. His new wife perished soon after their marriage from a snakebite, and suddenly Benga felt he had no reason at all to stay in the Congo.

When Verner returned to America, so too did Benga—but it was a worse fate than before.

Marius Burger, Wikimedia Commons

Marius Burger, Wikimedia Commons

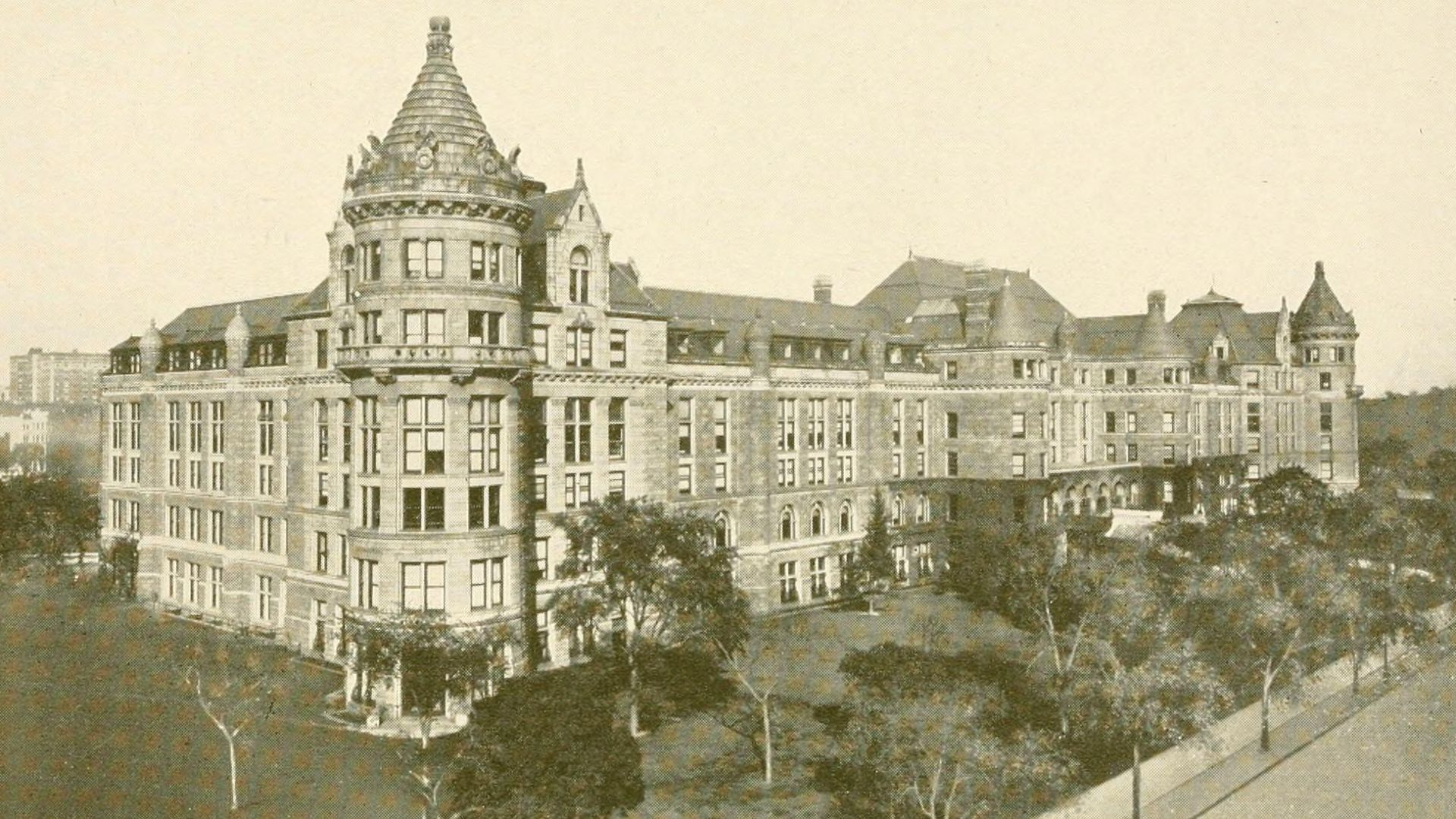

28. He Lived In A Museum

Benga accompanied Verner to New York, where the American got him a spare room at the Museum of Natural History under the watchful eye of curator Henry Bumpus. Bumpus, as interested in Benga as the Expo audiences had been, gave the Congolese man a southern-style linen suit to wear and had him act as a kind of usher when company came over.

The suit was more a costume for a doll than clothing for a man—and Benga quickly realized he had made a grave mistake.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

29. He Was Lost Between Two Countries

During this time, Ota Benga began feeling intense pangs of homesickness. He was now caught in an impossible position—neither at home in Africa nor fully accepted in America. The claustrophobic atmosphere of the museum only added to this feeling, and Benga’s frustration and sadness grew. Before long, Benga started to act out.

Janwillemvanaalst, Wikimedia Commons

Janwillemvanaalst, Wikimedia Commons

30. He Took Out His Anger

Benga tried to vent these emotions by playing once more at the “savage” that everyone apparently seemed to think he was. When he was once asked to seat the wife of a rich donor at the museum, Benga pretended to not understand and instead threw the chair across the room in the direction of the woman.

It clearly wasn’t working out with the museum, but that doesn’t excuse Verner and Bumpus’s next solution.

After Schweinfurth: "In the heart of Africa.", Wikimedia Commons

After Schweinfurth: "In the heart of Africa.", Wikimedia Commons

31. He Ended Up At A Zoo

In 1906, Benga’s “friends” came up with an infamous plan. Verner and Bumpus brought him to the Bronx Zoo in New York, where he was initially supposed to help clean and maintain the animal habitats. After all, Benga clearly needed a hobby and couldn’t be stuck inside any longer. As expected, this quickly turned sour.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

32. People Saw Him As A Money-Maker

The zoo’s director, William Hornaday, immediately remarked that visitors were far more interested in Benga than they were any of the exotic animals. To Hornaday, the next step was clear: Benga should become a part of the animal exhibition. Of course, he didn’t think he could say that right to Benga’s face, so his tactics were much more sinister.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

33. They Manipulated Him

While working at the zoo, Benga became especially close to an orangutan named Dohong, also known as “the presiding genius of the Monkey House”. Knowing that Benga spent most of his time with Dohong, the zoo prodded Benga to hang his hammock in the enclosure, and also set up a target nearby for him to shoot his bow and arrow at.

It was all downhill from there.

34. He Turned Into An Exhibit

On September 8, 1906, crowds at the zoo entered the Monkey House to find Ota Benga also on display. Eventually, a sign there listed Benga’s name, age (23), height (4 feet, 11 inches), and weight (103 pounds). It also stated that he was “Brought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State…by Dr Samuel P Verner” and that he was “exhibited each afternoon during September”.

It took no time at all for chaos to break loose.

35. He Sparked An Uproar

The public immediately erupted at the exhibition, with many African-American clergymen denouncing the “attraction” of Ota Benga. As Reverend James Gordon put it, “Our race, we think, is depressed enough, without exhibiting one of us with the apes...We think we are worthy of being considered human beings, with souls”.

Depressingly enough, however, publications like the New York Times countered that Benga, as a pygmy, was so “low in the human scale” that he could hardly be suffering. This wasn’t the only indignity.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

36. He Got No Money

Throughout all his time at the Bronx Zoo, there is not one shred of evidence that Benga was ever paid for his work. Moreover, the sly handling of his “exhibition” continued—after the public uproar, the zoo explicitly allowed him to roam freely, yet somehow the crowds always seemed to find him. Well, Benga had his own tactics to deal with this.

37. He Got Revenge

When people tracked him down at the zoo and began watching him like an exhibition, Benga hit back the only way he could. Since the zoo had given him a bow and arrow to make him seem like a proper “savage,” he obligingly turned the weapon on visitors, particularly the ones who mocked him. When people chased, poked, and prodded him, he also sometimes lashed out physically at them.

As Hornaday wrote to Verner, “I regret to say that Ota Benga has become quite unmanageable”—It got him exactly what he needed.

Jim Griffin, Wikimedia Commons

Jim Griffin, Wikimedia Commons

38. They Finally Let Him Go

The Bronx Zoo had wanted a crowd-pleaser, not an unruly human being, and they finally decided to take Benga’s “exhibition” down after he’d hit back at provoking visitors one too many times. With very little ceremony and no salary, they removed him from the zoo quietly and quickly.

Benga was at the beginning of a new phase once more, and he landed in a surprising place.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

39. He Got A New Savior

After leaving the zoo, Benga ended up under the care of Reverend James Gordon, the man who had supported him during the controversy of his exhibit. Gordon not only had Benga relocated to Lyncburg, Virginia, he also capped Benga’s teeth, bought him American-style clothes, and arranged for a tutor to improve his English.

Gordon was doing what he thought was best: Assimilating Benga and forcing people to see he was human, not an attraction. But Benga had other ideas.

40. He Did What He Wanted

In the end, Benga didn’t want much to do with Gordon’s improvement plan. Once his English was merely passable, Benga stopped his education to go work in a tobacco factory. Maybe he felt that dressing up as and playing the American gentleman was just as constraining as playing the savage.

He also had one big dream left.

Chris Allen, Wikimedia Commons

Chris Allen, Wikimedia Commons

41. He Had One Last Wish

Free from the Louisiana Exposition and free from the Bronx Zoo, Benga harbored a heartbreaking desire. He wanted, at long last, to return to Africa for good. He was now a full adult, and he wanted to be in control of his own destiny and around people who might truly understand him.

Yet all those dreams were dashed in an instant.

David R. Francis (book author), Wikimedia Commons

David R. Francis (book author), Wikimedia Commons

42. His Dream Was Crushed

In 1914, Ota Benga got perhaps the worst news of his life: WWI had broken out, stopping all civilian ship traffic across the ocean for the foreseeable future. Just like that, all of Benga’s years of hoping and planning to return to Africa were gone. He had only one solace left—and even then, it wouldn’t be enough in the end.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

43. His Friend Left Him

During this time, Samuel Verner—the man who had brought Benga to America in the first place—all but disappeared from his life. He still kept in occasional contact, but was mostly wrapped up in his own career and money troubles, and had willingly let Benga go into the care of Reverend Gordon. Nonetheless, Benga had a new support system.

44. He Took Boys Under His Wing

During his time in Lynchburg, Benga made friends with some local boys, and would often trek off with them in the forest to teach them how to hunt wild turkeys and squirrels, as well as how to trap other small animals. The boys would also listen as he told them of hunts past, when his quarry were elephants—but hunting wasn’t all he taught them.

J.P. Bell Co. , copyright claimant, Wikimedia Commons

J.P. Bell Co. , copyright claimant, Wikimedia Commons

45. He Shared His Rituals

On certain special nights, the neighborhood boys would get the privilege of watching Benga build a fire and then dance and sing around it, in an echo of the rituals he must have performed when he was young, an ocean and decades away. For a time, this must have sustained Benga enough to keep trying, but soon the boys noticed a change.

46. He Fell Into A Depression

As time went on, particularly after the outbreak of the war, Benga underwent a startling transformation. He no longer wanted to hunt with the boys, and no longer went up to them for a chat, or a smile, or anything at all. In hindsight, he was settling into an all consuming depression—and he was obsessed with one thing only.

47. He Couldn’t Stop Thinking About Africa

The further away his dream of returning to Africa went, the more Benga fixated on his homeland. At times, the boys described how he would sit alone, under a tree, and stare in silence for hours at a time. When he did make a noise, it was often to sing a song he had learned in his American travels: “I believe I’ll go home / Lordy won’t you help me”.

The homecoming he had was much more tragic than all that.

Jean Audema (1864-1936), Wikimedia Commons

Jean Audema (1864-1936), Wikimedia Commons

48. He Performed One Last Ritual

Late in the afternoon of March 19, 1916, the neighborhood boys watched as Benga built a fire in a field, as he had done many times before. He then danced and chanted around it, again as he had done many times before. But something was different this time. The boys noted even then that Benga seemed deeply sad, though they couldn’t fathom just how deep that sadness went.

49. He Shot Himself

By now, Benga was around 32 or 33 years old, and entirely out of hope that he would ever see his home again, or that he would ever fit in inside America. That night after the boys watched him perform the ritual dance, Benga snuck into the shed across from his home, retrieved a gun, and in the early morning hours shot a single bullet into his heart.

He was gone, but he may have also left one message behind.

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

Jessie Tarbox Beals, Wikimedia Commons

50. He Was Finally Free

When the locals found Ota Benga’s body, they reportedly noticed one disturbing change. Some say the Congolese man had chipped off the caps on his filed teeth, apparently in an attempt to come back to himself again one last time. Although this detail may be apocryphal, it does give a poignant snapshot of Benga’s decades-long alienation from kin and country.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

The Four-Legged Woman Of Texas

The Extraordinary Life Of The Tallest Man Who Ever Lived

The Disturbing Life Of The Real Tom Thumb