An Imitation Game

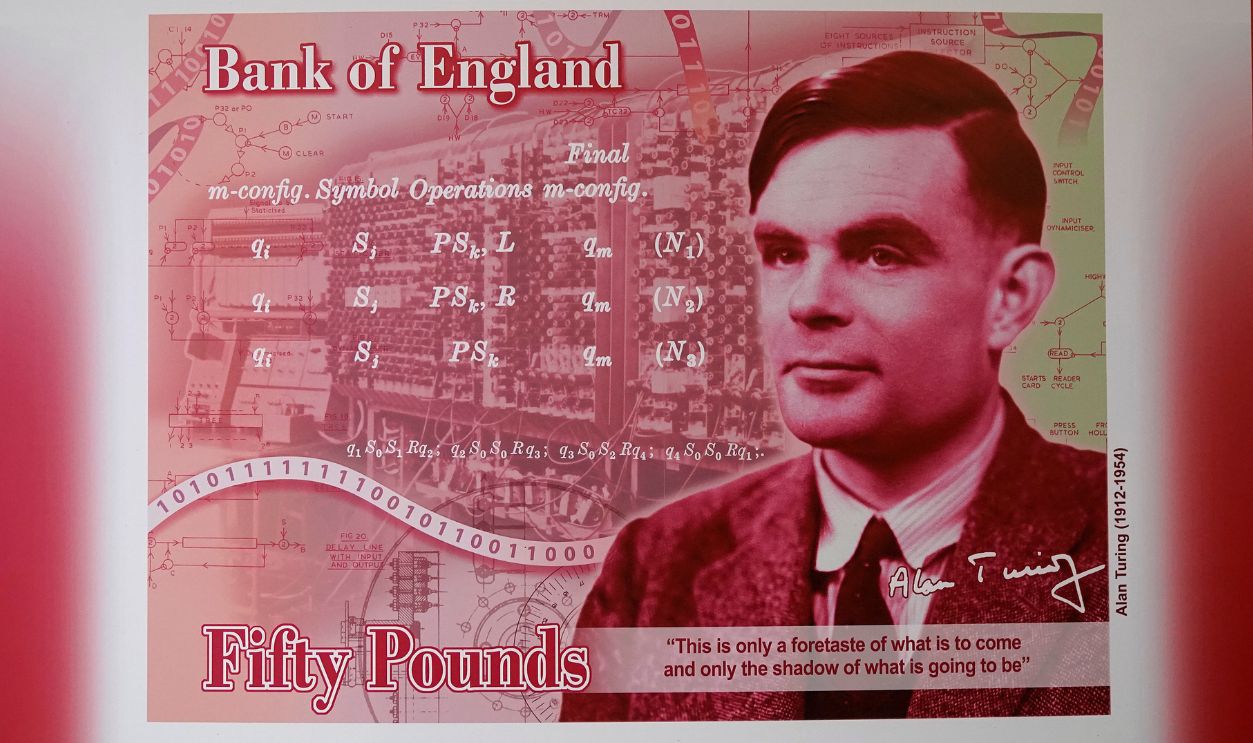

The world owes so much to Alan Turing. Without his quick and clever mind, the Allied Forces may never have been able to unravel the impossible messages produced by the German Enigma machine. WWII would have looked very different without that knowledge.

Despite this, the British government detained Turing simply for being himself. Let’s shine a light on the true Alan Turing—and all he’s done for the world.

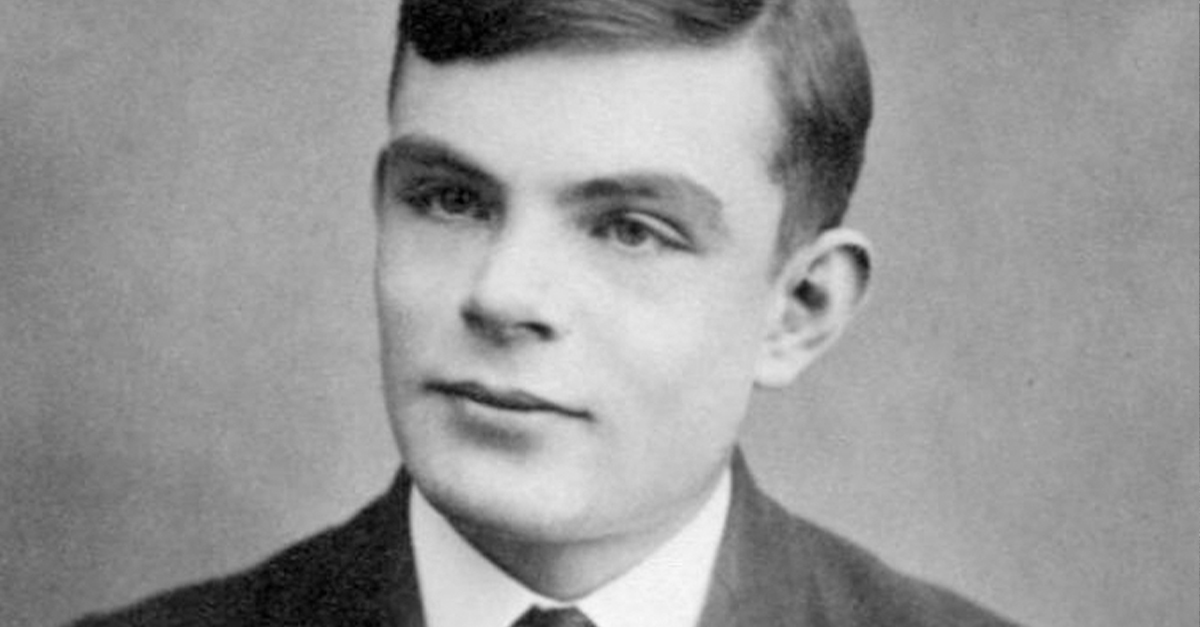

1. He Had A Good Start

Alan Turing was born on June 23, 1912. He was the second son of Julius and Ethel Turing and grew up fairly well off. His father was a member of the Indian Civil Service, which meant that his parents often traveled between their home in England and India. However, Turing and his brother remained home, growing up under the watchful eye of a retired army couple.

Even early in his life, Turing proved that he had an extraordinary mind.

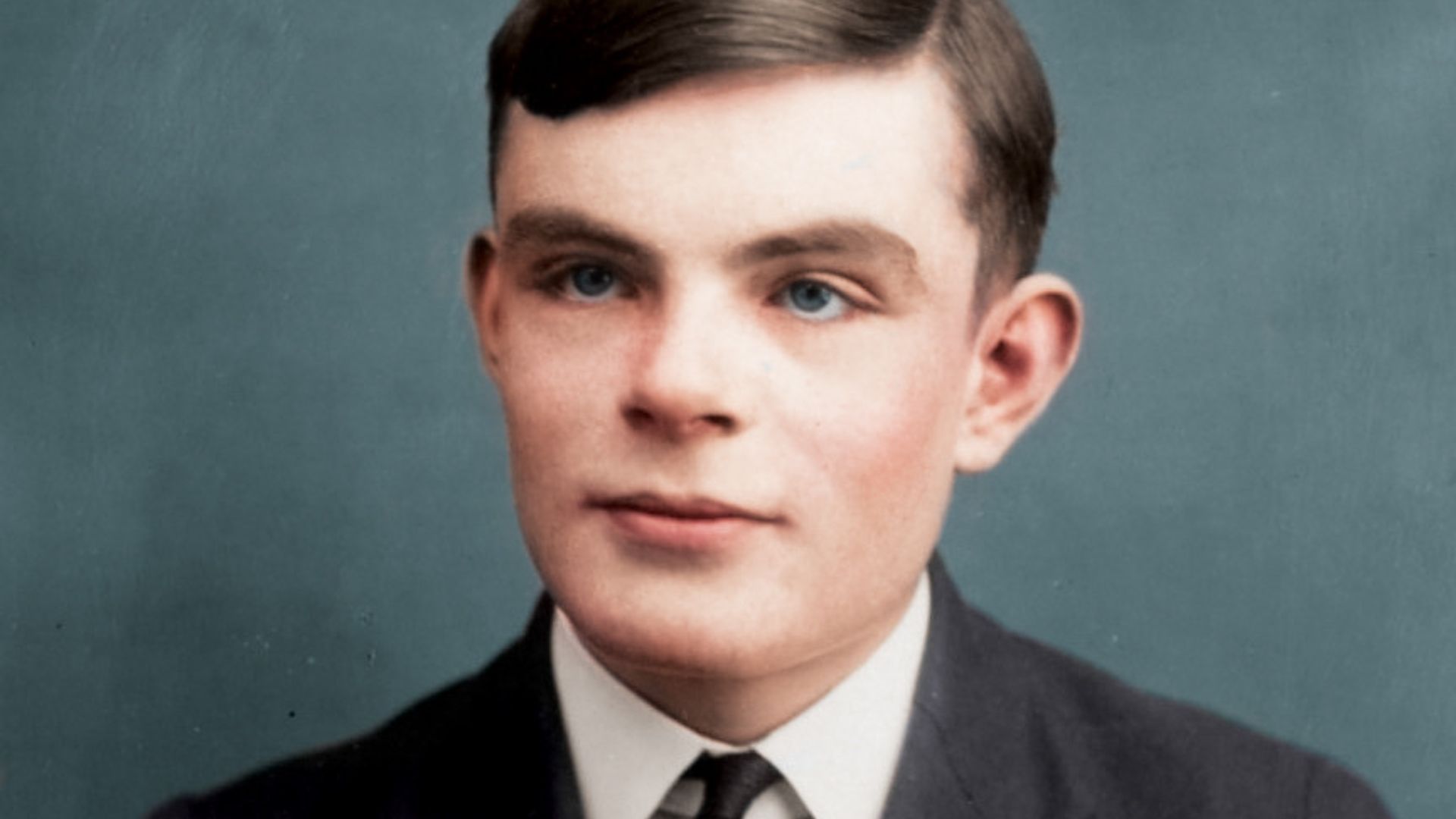

Possibly Arthur Reginald Chaffin (1893-1954), colorized by @frommonotopoly, Wikimedia Commons

Possibly Arthur Reginald Chaffin (1893-1954), colorized by @frommonotopoly, Wikimedia Commons

2. He Was A Genius

Between the ages of six and nine, Turing completed his studies at St Michael’s primary school. He was so impressive that he even caught the eye of the headmistress. According to her, she “… had clever boys and hardworking boys, but Alan is a genius”.

It seemed that even at this young age, Turing was destined for greatness. Sadly, though, he had no clue that this greatness would be so wrapped up in tragedy.

3. He Was Determined

At the age of 13, Turing began attending Sherborne School—a boarding school in Dorset. His first day as a student there, however, proved how determined he could be. That fateful day lined up with the 1926 General Strike, which involved railway men and affected his commute. But this didn't stop Turing from getting to class on time.

With a 60-mile journey stretched out before him, Turing hopped on his bicycle and began pedaling from Southampton to Sherborne. It was a demonstration of immense willpower—a character trait that would follow him into adulthood.

4. His Mind Was Unparalleled

Turing’s mind seemed tailor-made for mathematics and science. These were his ultimate passions. By the age of 15, Turing could solve advanced problems—but that wasn't the most shocking part. You see, he had never actually studied elementary calculus. These areas of study brought him joy, even if it did not bring him friends.

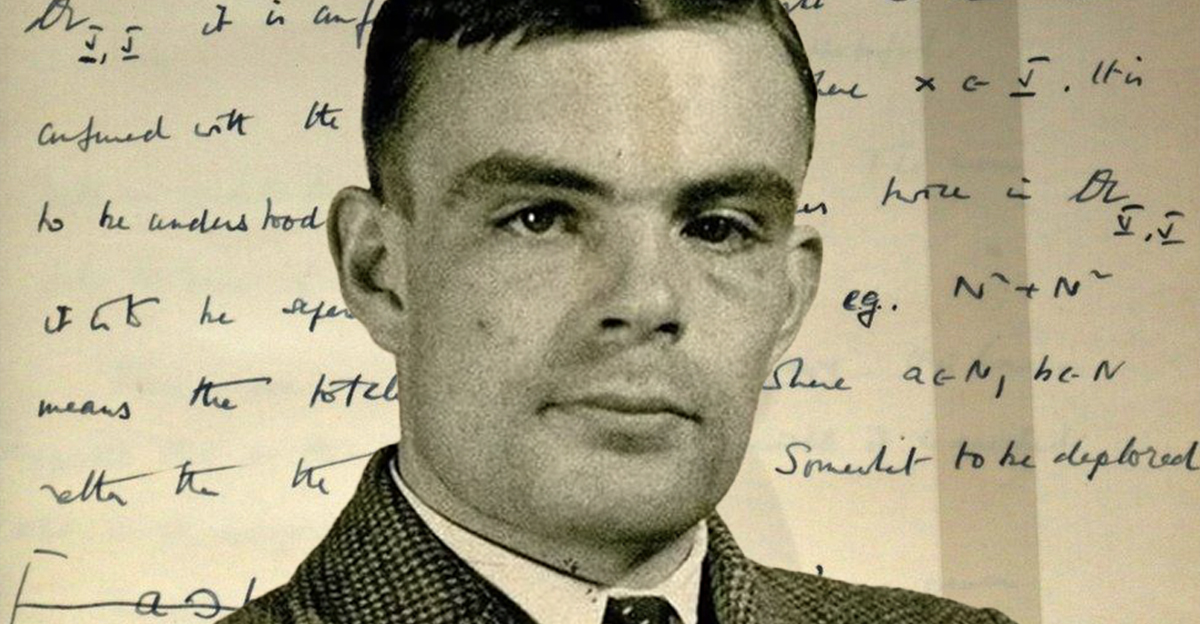

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

5. He Didn’t Fit In

Turing’s talent did not earn him many friendships. Even his teachers viewed Turing as a potential problem. During this time, educational systems such as Sherborne valued the classics—literature and philosophy. His headmaster woefully informed Turing’s parents, “if he is to stay at public school, he must aim at becoming educated. If he is to be solely a Scientific Specialist, he is wasting his time at a public school”.

Despite this warning, he remained at Sherborne—and a good thing too. After all, he met someone there who changed his life forever.

Pictures from History, Getty Images

Pictures from History, Getty Images

6. He Met A Boy

Turing may not have been a popular boy at Sherborne—but he did manage to make one lasting connection. Turing met Christopher Collan Morcom during this time. The young boys formed a deep and significant relationship. Morcom has been described as Turing’s first love—though, if it was love, it never had the chance to flourish.

7. He Lost His First Love

Christopher Morcom succumbed to complications of bovine tuberculosis, an illness he’d been suffering from for several years, in February 1930. This passing affected Turing deeply. In the years that followed, he maintained a close relationship with Morcom’s mother. He also managed his grief by throwing himself into the subjects that mattered to him most.

Turing believed that all the passion he poured into his work was exactly what Christopher would have wanted him to do. What's more? All of this dedicated study laid the foundations for his next chapter.

8. He Succeeded Easily

Turing's love of science and mathematics led him straight to King’s College, Cambridge, where he excelled. They awarded him first-class honors in mathematics. He carried on with his studies, entering a master’s course, and eventually becoming a Fellow of King’s College.

The gears of Turing's mind never seemed to stop turning—and in 1936, he wrote one of the most important papers of all time.

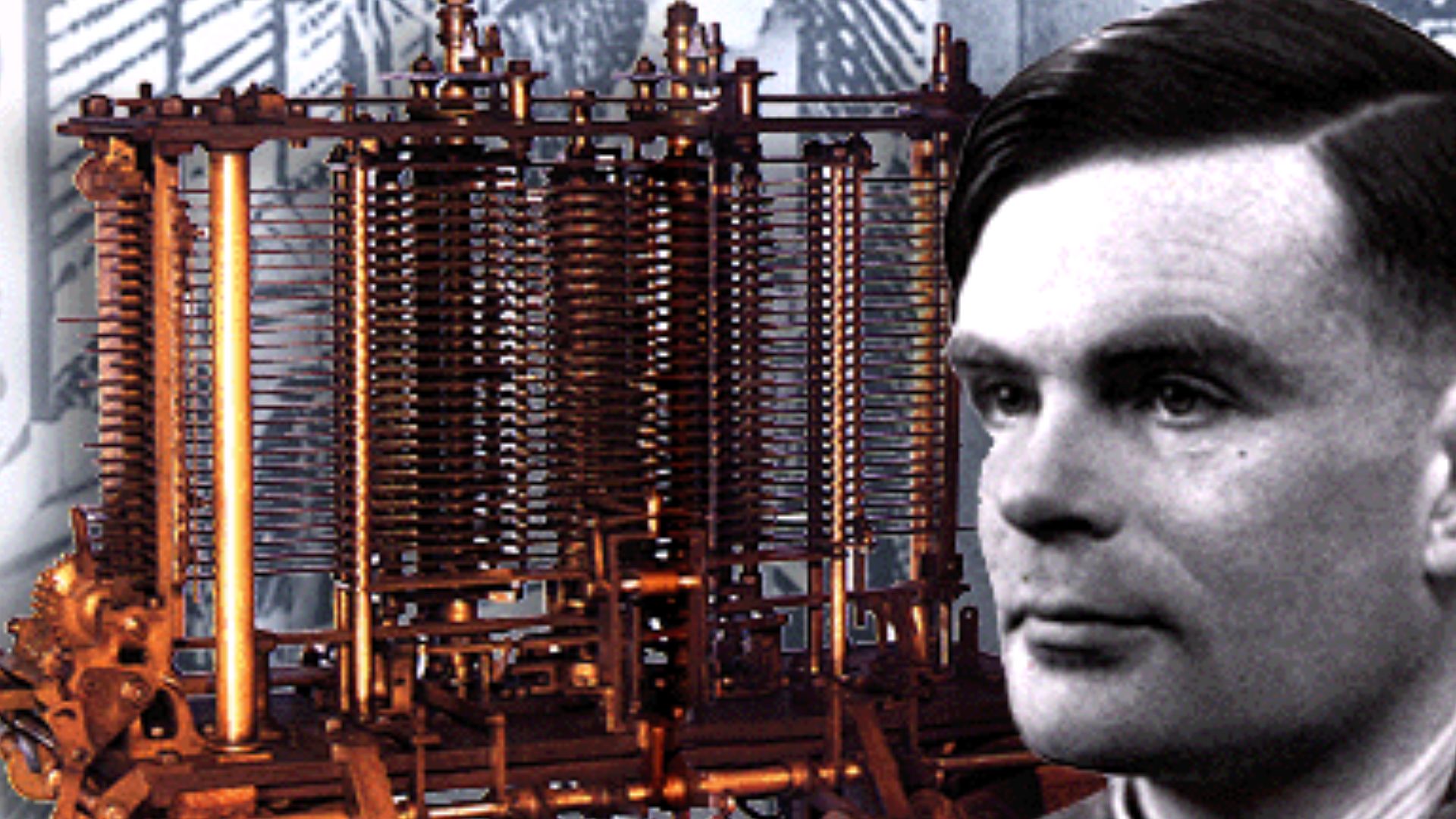

Jean-Christophe BENOIST, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Christophe BENOIST, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

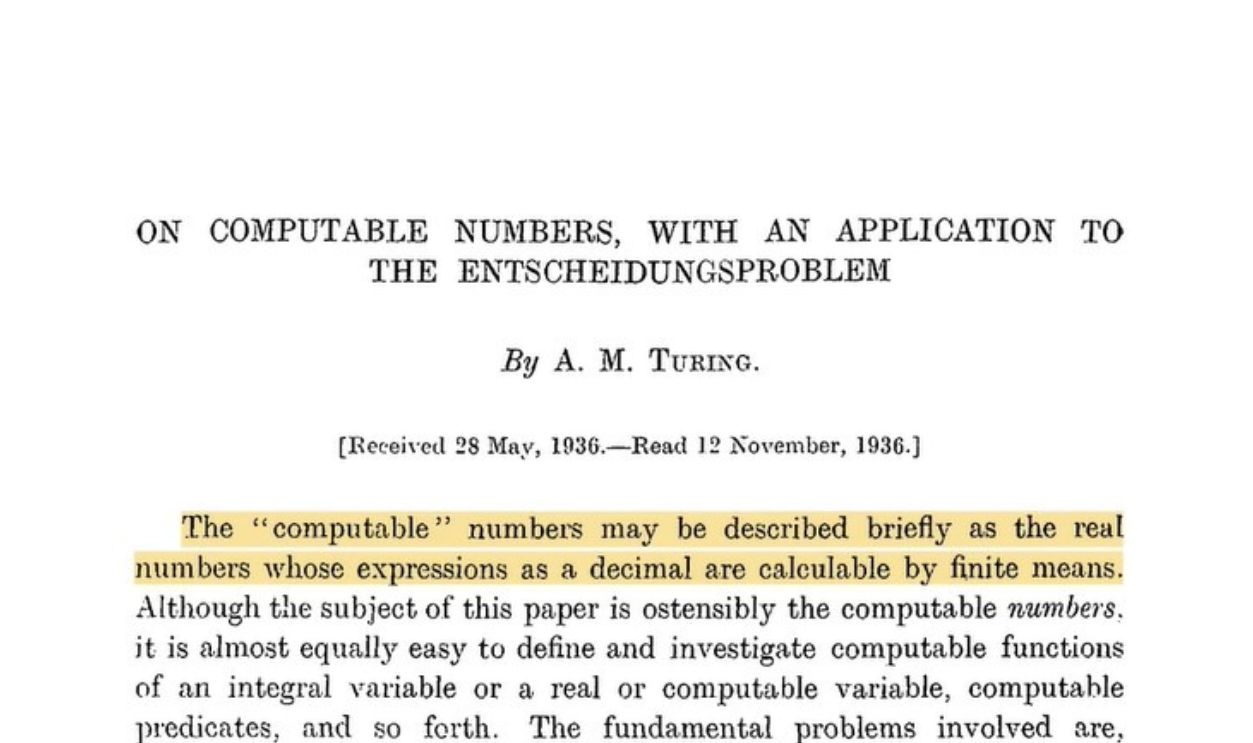

9. He Wrote A Brilliant Paper

Turing worked on several projects and papers—but there was one paper that stood above all the rest. This was his May 1936 paper, “On Computable Numbers, with an Application to Entscheidungsproblem”. In this paper, Turing proposed a hypothetical device that, in theory, could compute any conceivable mathematical computation if written as an algorithm.

This device became known as the Turing machine—and Turing Machines would eventually save the world.

10. He Continued His Studies

People have called Turing’s paper, and his Turing machines, “easily the most influential math paper in history”. However, in the late '30s, Turing machines were theory alone. It garnered Turing much talk in mathematical communities, but little else. He carried on with his studies, moving to Princeton University to study under mathematician Alonzo Church. Turing gained a PhD in Mathematics from Princeton in June 1938, and returned to the UK.

Little did he know, there were already storms brewing on the horizon.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

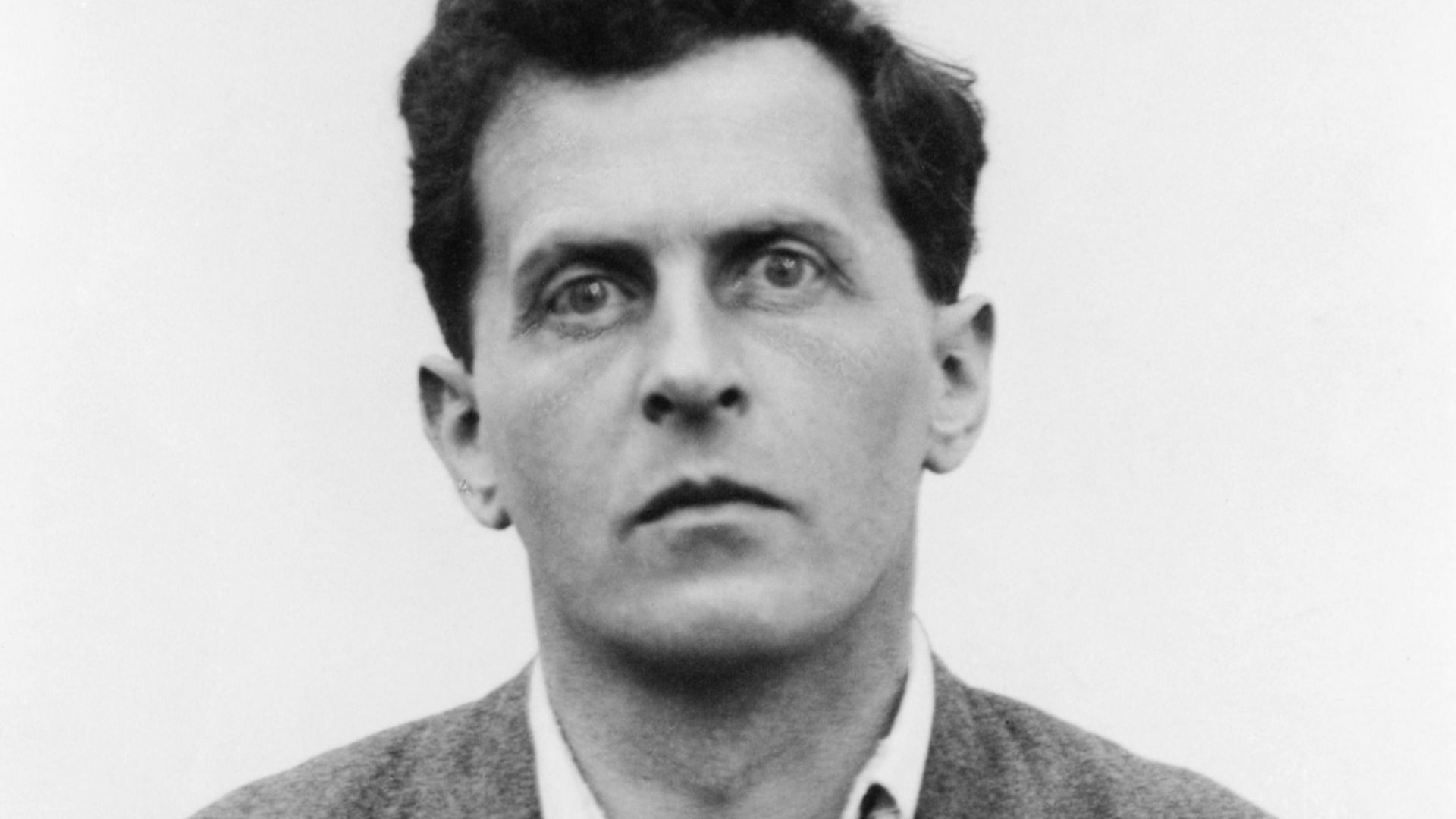

11. He Could Be Difficult

Turing was a genius. However, his genius came with complications. Turing rarely feared voicing his opinions. Upon returning to England, he attended a series of lectures on the foundations of mathematics by Ludwig Wittgenstein. Turing and Wittgenstein had opposing views on mathematics, resulting in them arguing throughout the series.

Turing certainly knew his own mind—a quality that undoubtedly came in handy when fate threw him a daunting curveball.

Moritz Nahr, Wikimedia Commons

Moritz Nahr, Wikimedia Commons

12. His Life Changed

Turing may have remained relatively unknown if the world had not erupted into conflict for the second time in such a short period. Wars are long and bloody things; however, what is rarely spoken about is how heavily they rely upon communication. The Allies won WWII because of the British’s ability to decode messages—and they needed Turing to accomplish this.

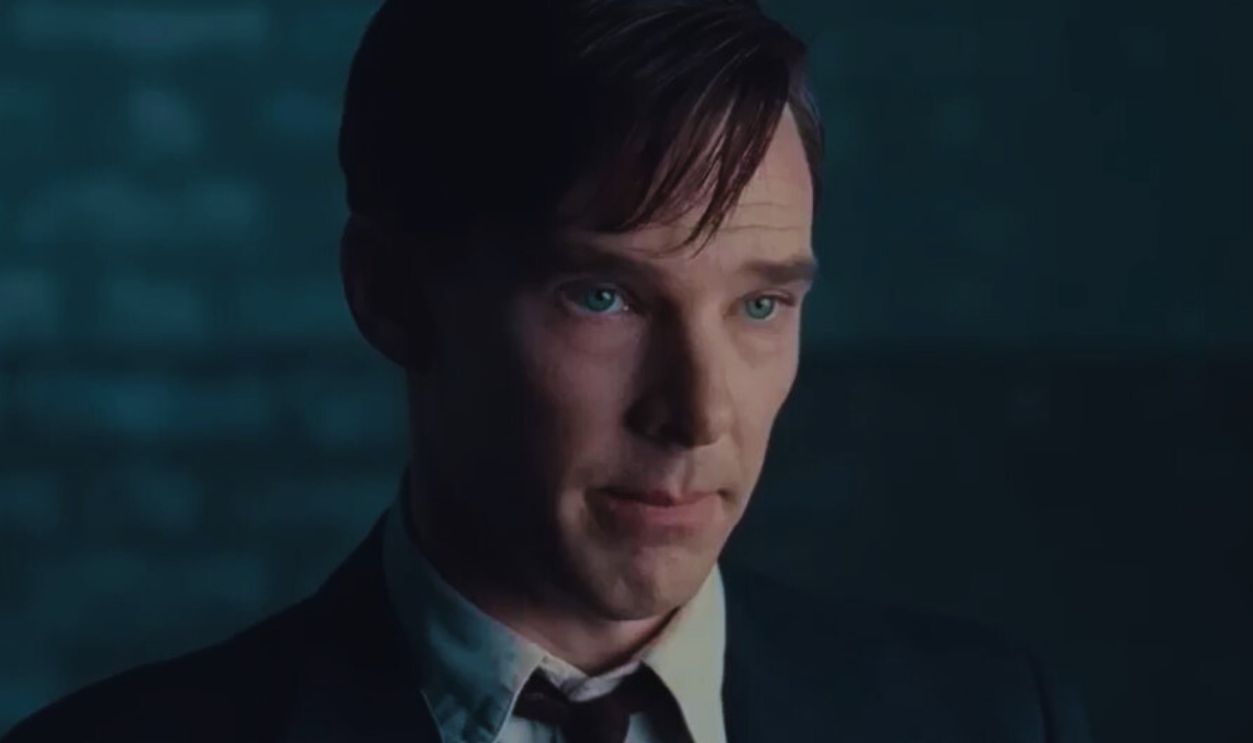

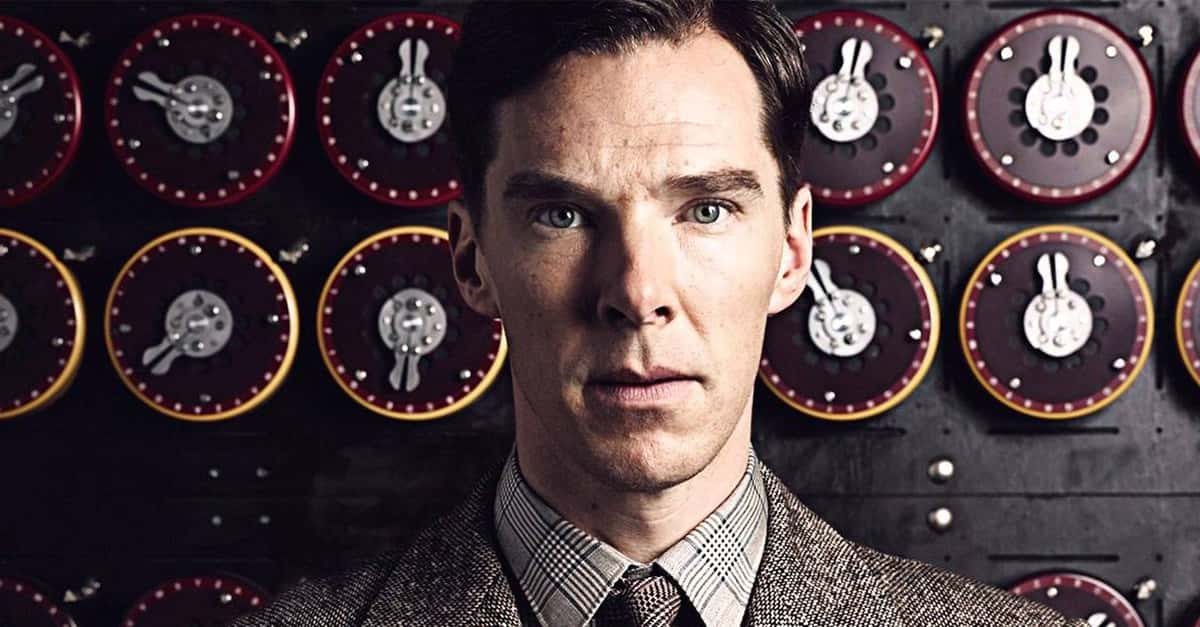

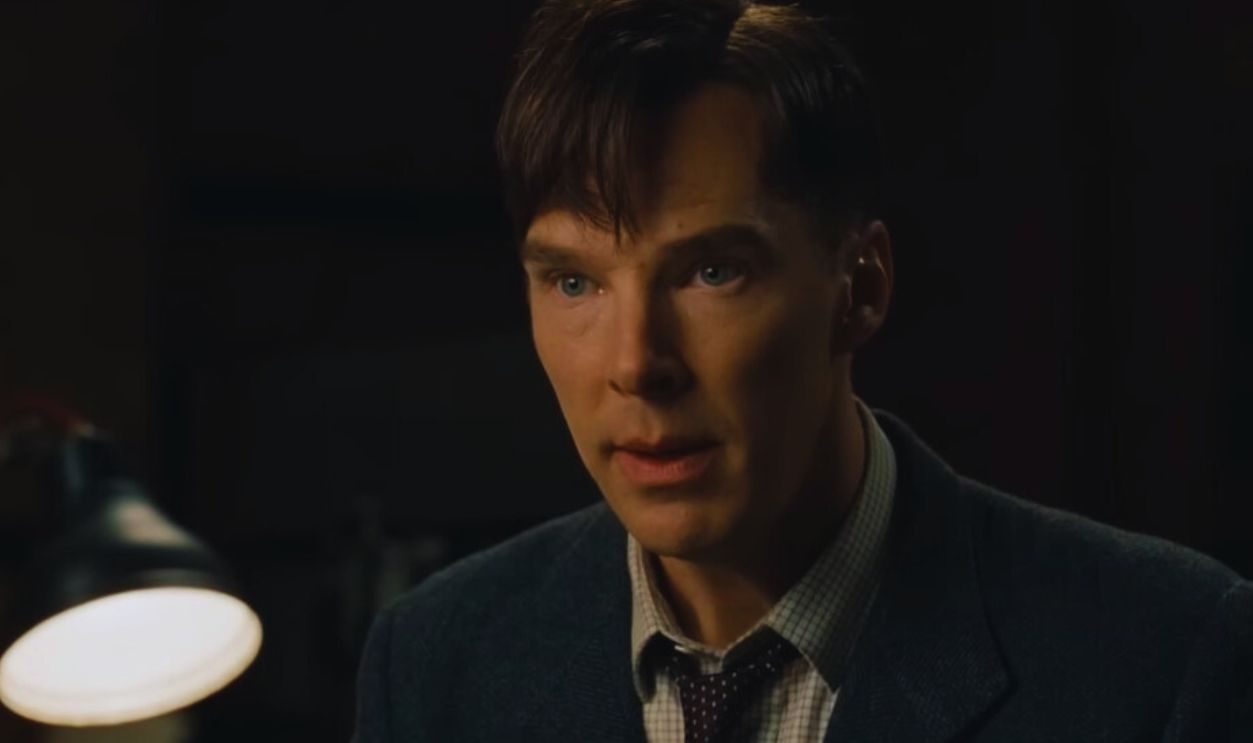

Turing breaks Enigma – The Imitation Game (2014), Weyland

Turing breaks Enigma – The Imitation Game (2014), Weyland

13. He Joined A Secret Group

Following the conclusion of WWI, the government created the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS). The goal of the school was to help aid British intelligence, both in peacetime and in the unfortunate event of another conflict. Turing became involved with GC&CS in September 1938.

He had one focus—something called the Enigma Machine.

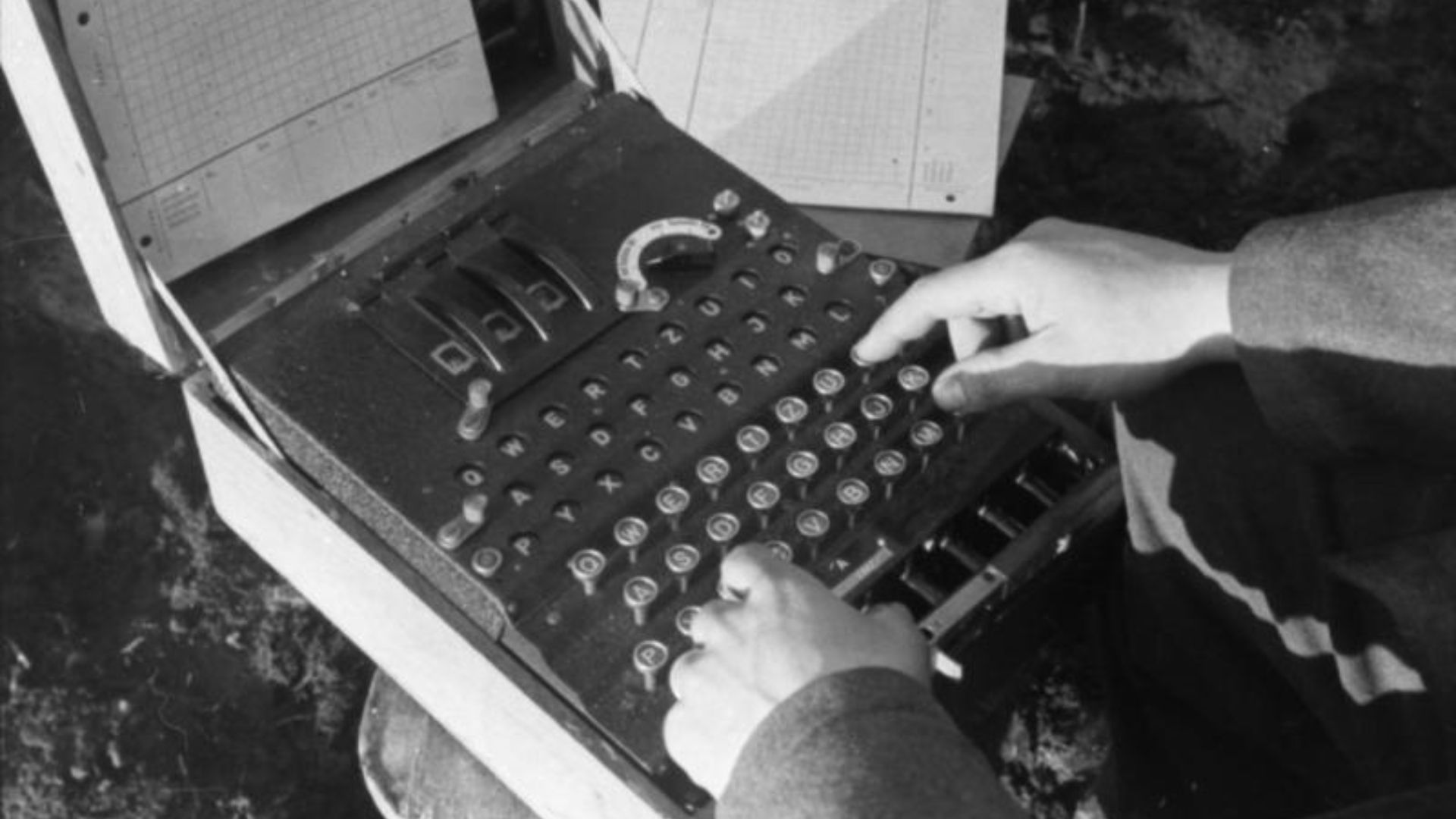

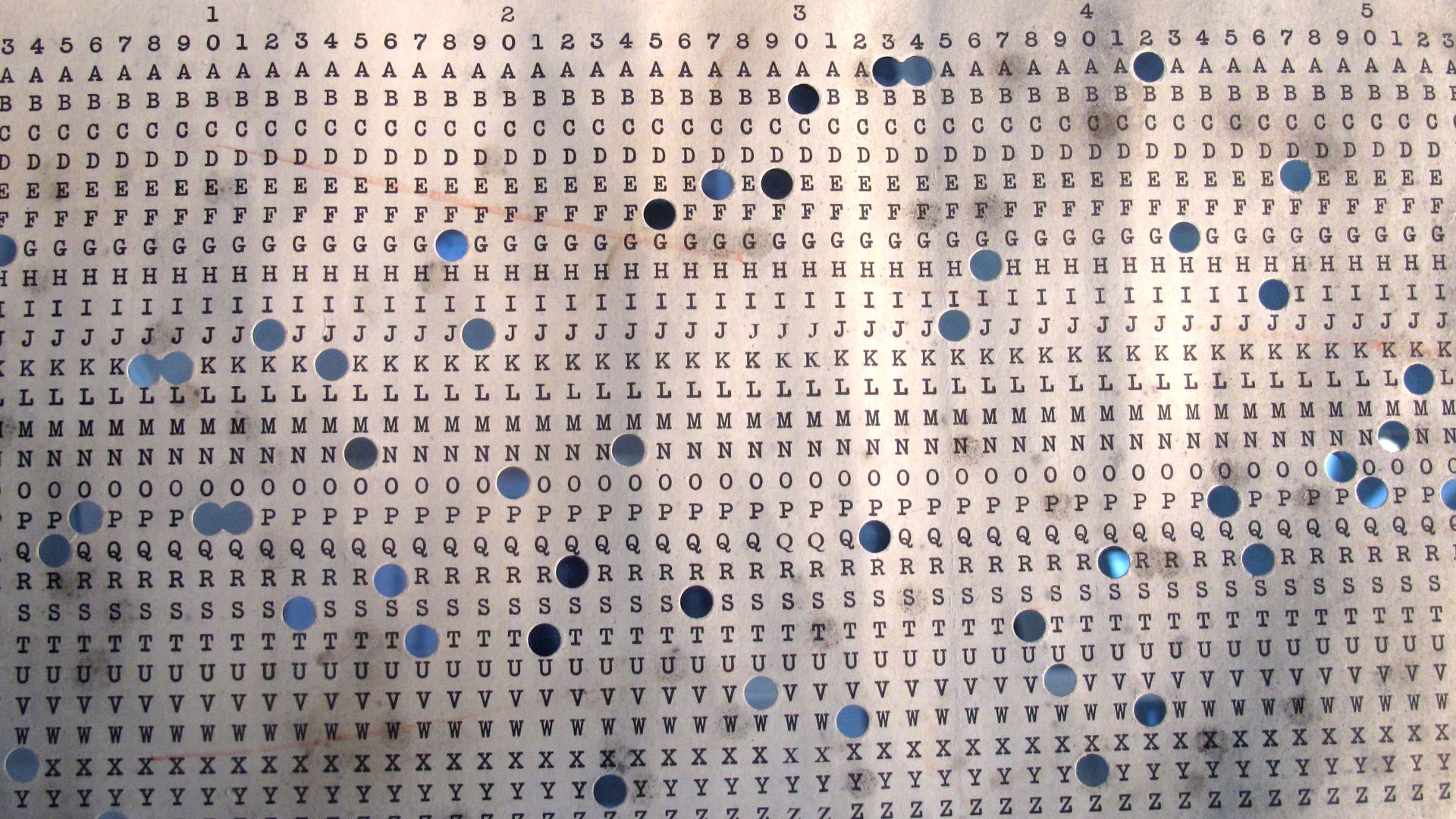

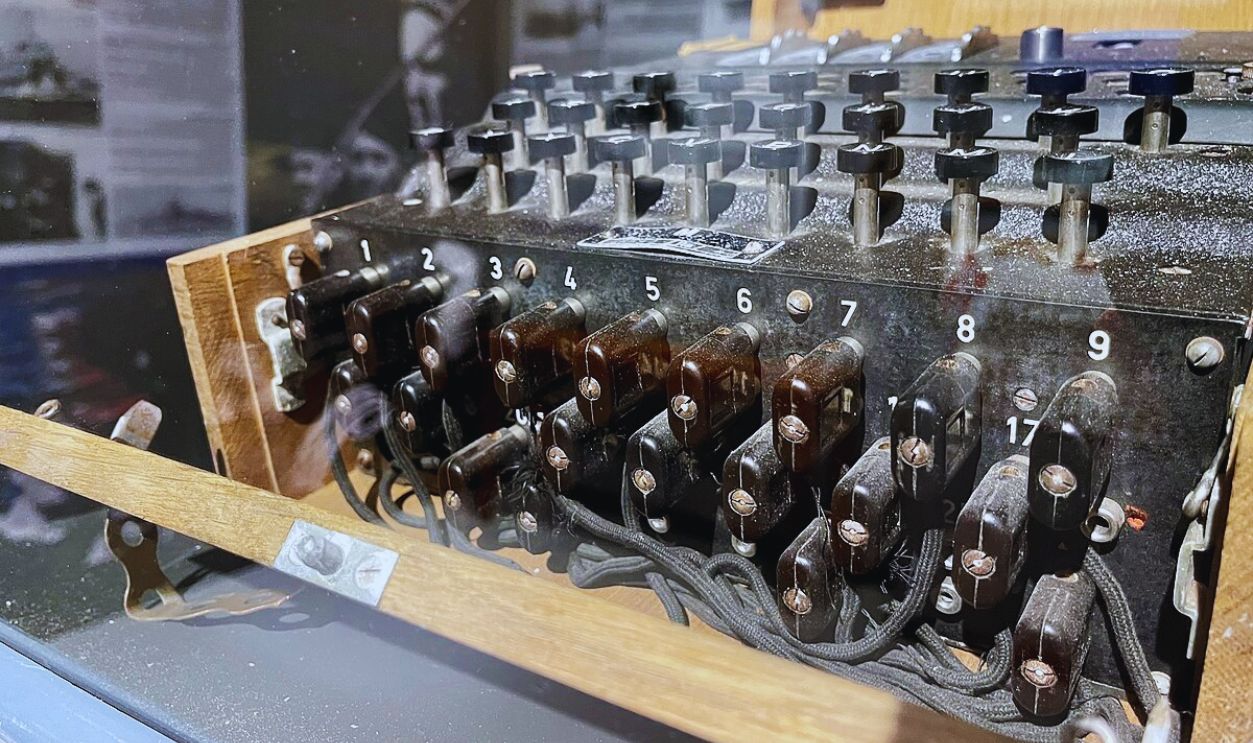

14. He Had A Problem To Solve

During WWII the Allied forces faced several enemies—not just the explosives or firepower of the German army, but also their Enigma machine. The Enigma machine was a device that scrambled the letters of the alphabet, enabling the creation of secret messages. It could create an unfathomable number combinations, and the Germans typically changed the “key” to the cipher daily.

Without cracking the Enigma’s secrets, the Allies had very little to work with.

15. He Had Help

While it took the conflict a longer time to reach the shores of England, Poland had been dealing with the threat of Germany for years by the end of the 1930s. Polish minds broke the Enigma’s secrets as early as December 1932. At a meeting in July 1939, they shared their knowledge of the Enigma with British and French intelligence.

Britain and Turing had the blueprints, but it was still grueling work to unlock the codes.

Pilsudski Institute London, Wikimedia Commons

Pilsudski Institute London, Wikimedia Commons

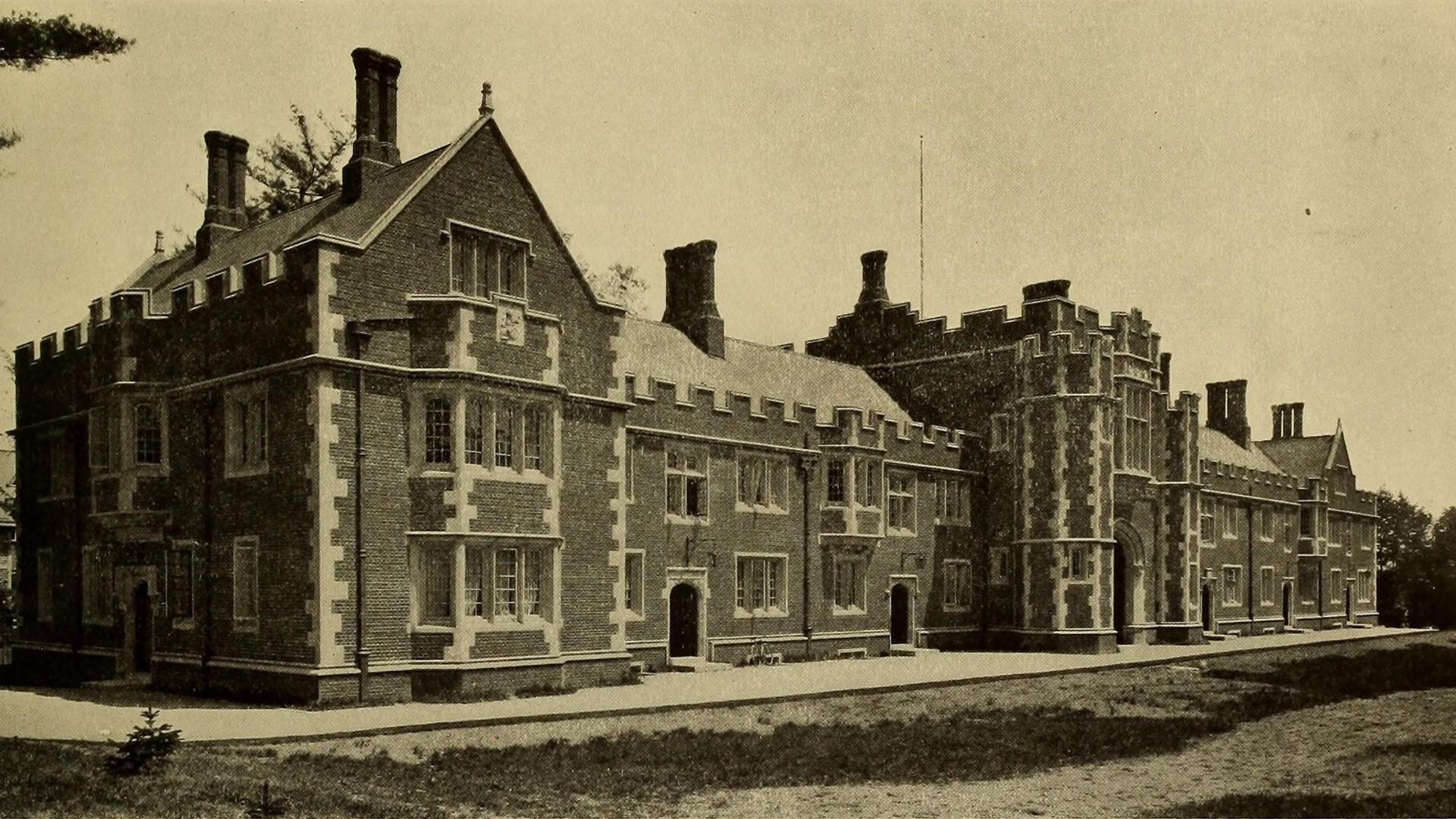

16. He Joined Bletchley

Bletchley Park is an estate about an hour north of London by train. In the 1930s, the estate included a modest manor house and sprawling lands. The head of MI6 bought the estate in May 1938, and by August 1939, the first members of GC&CS began to populate Bletchley Park. Turing would soon be among them.

Paul Buckingham , Wikimedia Commons

Paul Buckingham , Wikimedia Commons

17. He Was The Best Of The Best

It became clear that what Britain needed was manpower—and, soon, Bletchley Park became the secret meeting location for some of the most brilliant minds. In the words of Asa Briggs, a fellow codebreaker, “You needed exceptional talent, you needed genius at Bletchley, and Turing’s was that genius”.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

18. He Needed Something More

The Polish Cipher Bureau had provided Turing and his fellow codebreakers with the basics. However, there was a worrisome problem with the Polish system. It depended on an indicator procedure that proved unreliable. So when the Germans eventually altered it in 1940, there was a brand new challenge to overcome.

Turing’s methods would prove to be far more effective.

RadioFan (talk), Wikimedia Commons

RadioFan (talk), Wikimedia Commons

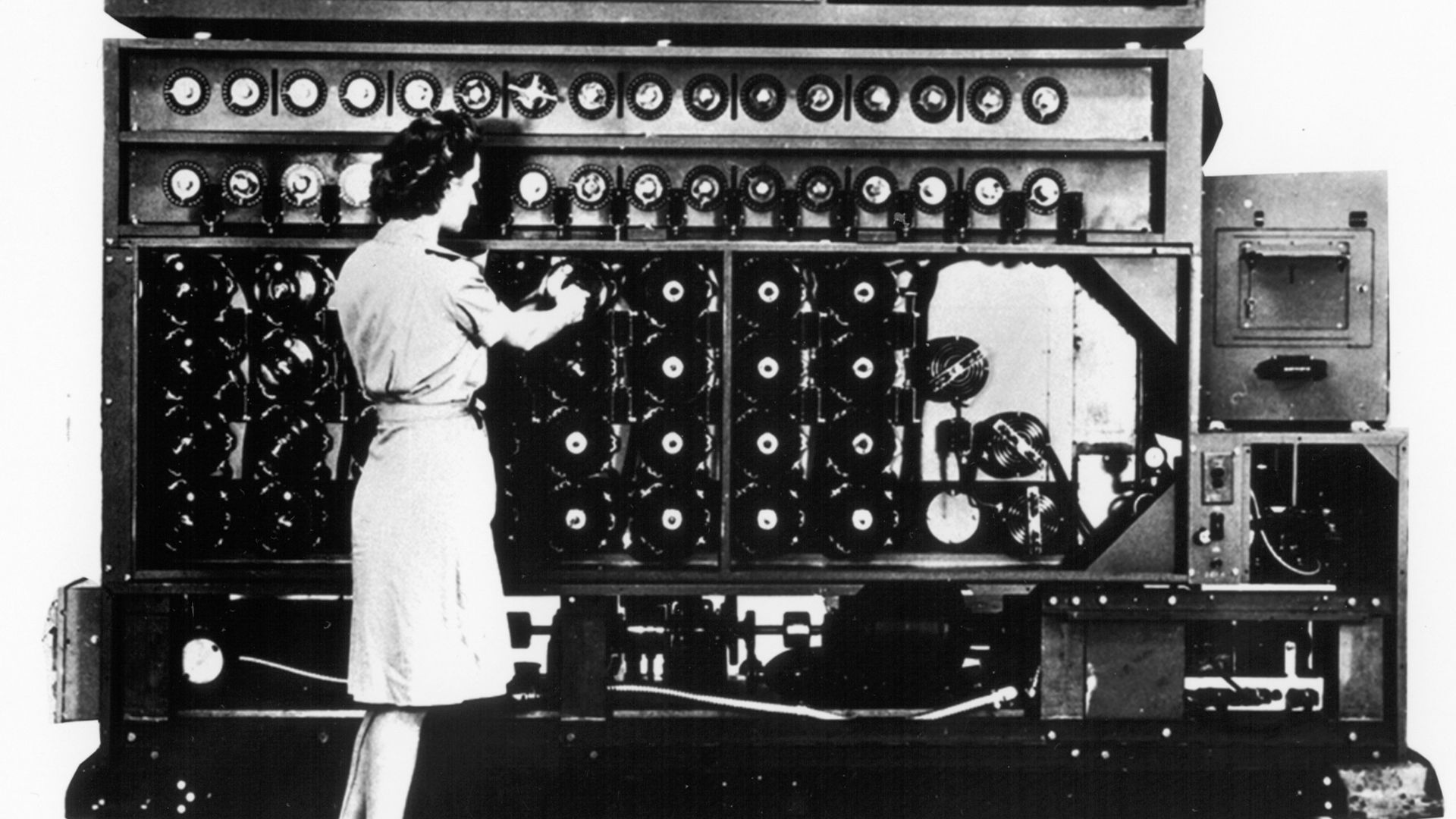

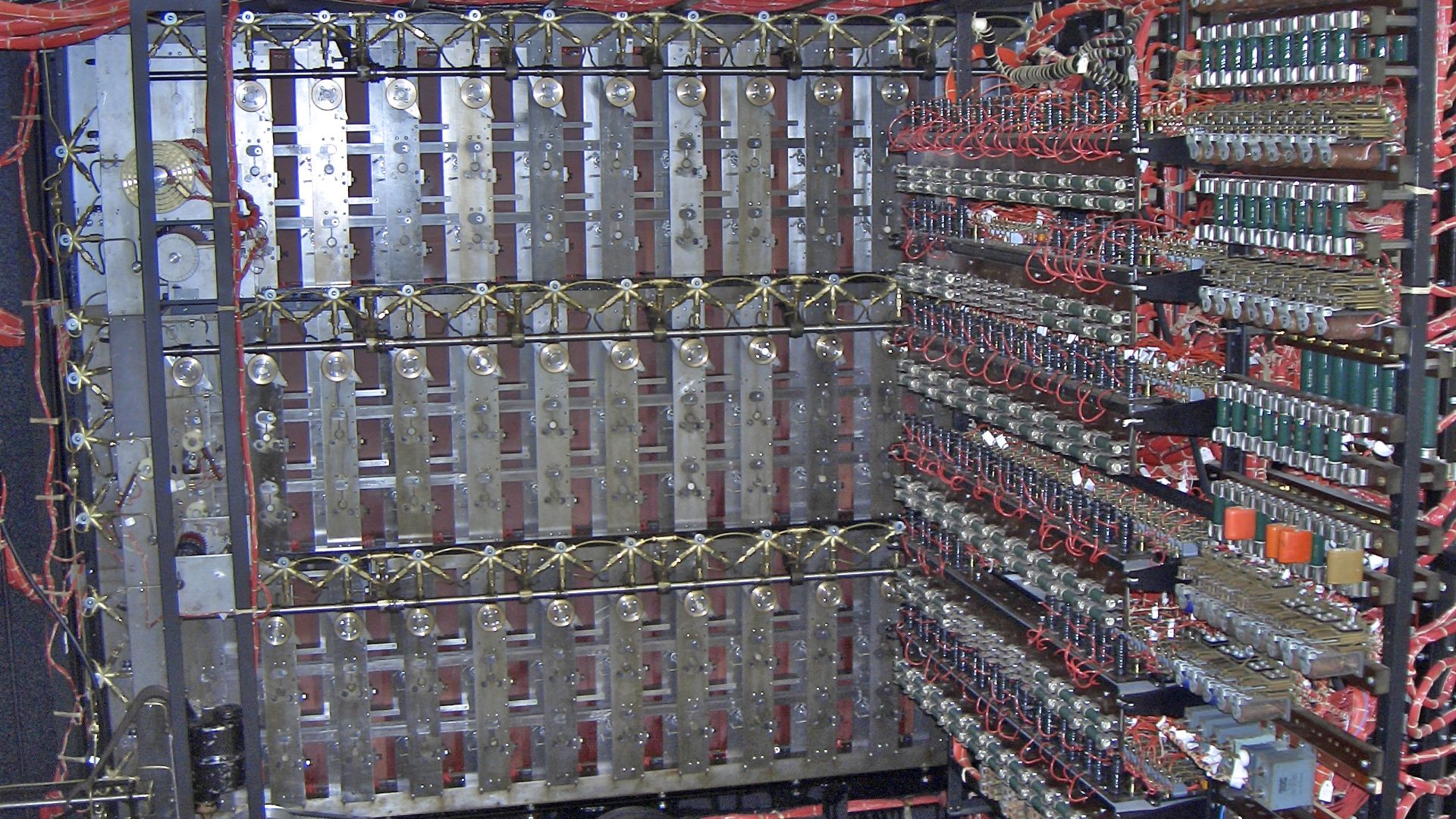

19. He Invented A Machine

It only took Turing weeks at Bletchley Park to improve upon the Polish bomba kryptologiczna. This machine was called the bombe. The bombe machines decrypted the Enigma code through a “crib," which was a term used at Bletchley to mark any known or suspected “plaintext” at any point in any enciphered message.

This allowed the Allies to better use their manpower, coming to solutions more quickly. They were indispensable to the effort. However, they were beasts to handle.

Ian Petticrew, Wikimedia Commons

Ian Petticrew, Wikimedia Commons

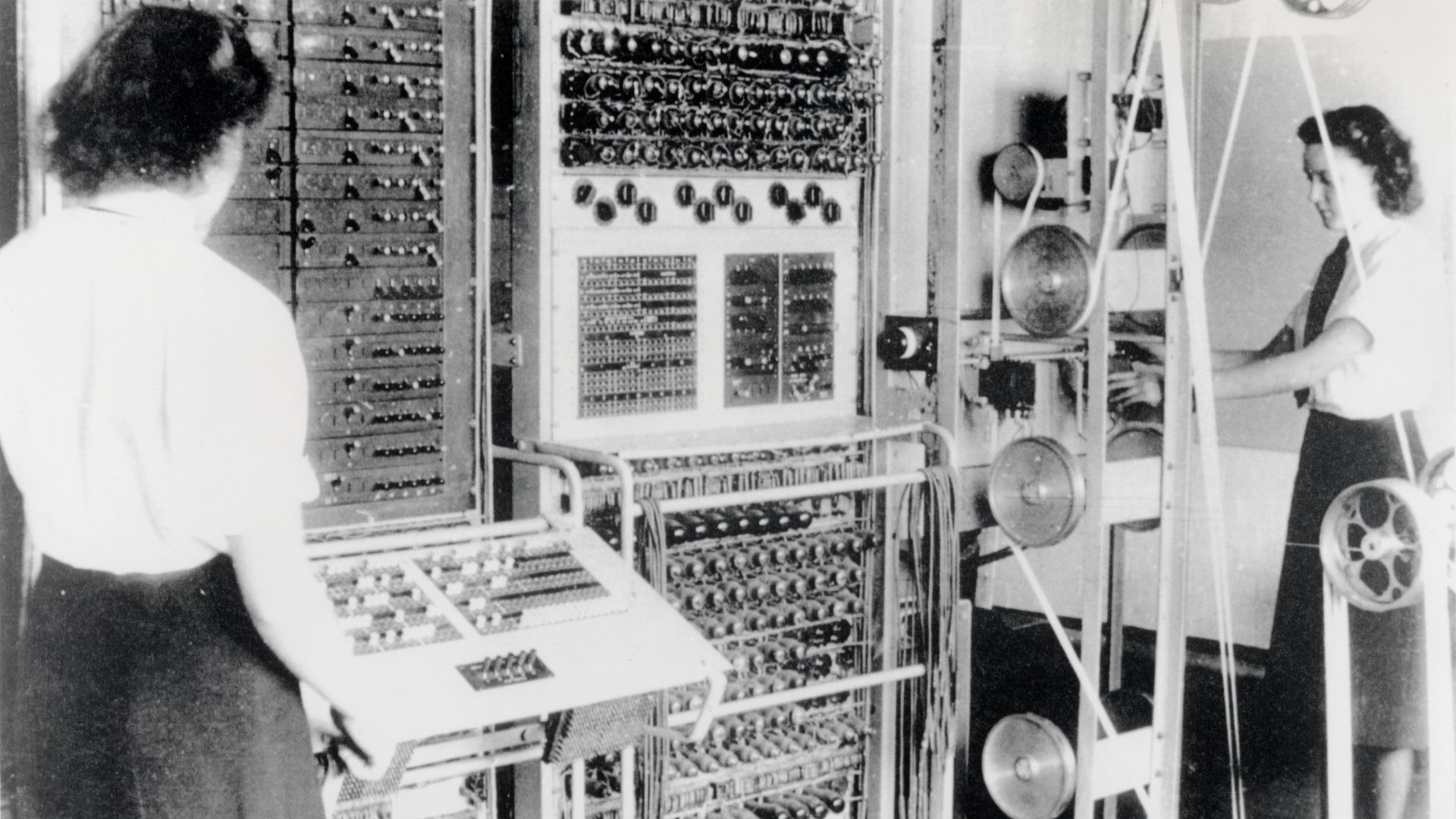

20. His Machine Was Huge

The bombe machine approximately weighed a ton, stood at over six feet, and had a width of seven feet. They operated through large tubes in the back that required being set manually. Bletchley assigned members of the Women’s Royal Naval Service (Wrens) to work with these machines, spending hours monitoring them and waiting for them to stop, before starting the whole process again.

They were essential. However, early on, they didn’t have enough of them.

National Security Agency, Wikimedia Commons

National Security Agency, Wikimedia Commons

21. He Didn’t Have Enough

Turing, along with his fellow cryptanalysts, had changed the course of the conflict; however, it was not enough, and by late 1941, frustrations were rising. They had invented the bombe, yet they did not have enough units, nor enough manpower to tackle all the signals. Finally, Turing and his cryptanalysts had had enough.

22. He Spoke Out

Taking matters into their own hands, the group wrote a letter to Winston Churchill in October. The letter, which named Turing first, emphasized how little they needed in relation to how many lives they could save if the government granted their request. Churchill's response was jaw-dropping.

Yousuf Karsh, Wikimedia Commons

Yousuf Karsh, Wikimedia Commons

23. He Inspired Instant Action

Upon receiving this letter, Churchill acted immediately. He reached out to General Ismay, writing, “ACTION THIS DAY. Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done”. By November 18, the wheels of change were finally in motion—and by the end of WWII, more than 200 bombes were in use at Bletchley Park.

Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., Wikimedia Commons

24. He Was Quirky

From afar, Turing was a brilliant man who contributed his genius to the war effort—but up close, his eccentricities took center stage. Although his coworkers at Bletchley Park remarked on the honor of having spent time with him, they also recalled his unique quirks.

25. He Had A Special Way Of Doing Things

Turing certainly stood out from the crowd. His peers witnessed him chaining his mug to the radiator, so that nobody would take it. He also rode his broken bicycle in the strangest way, keeping track of his pedaling so that its chain wouldn't come loose. Instead of fixing it, he would just pause to readjust the chain as he went along.

Turing always did things his way—and oftentimes, his way turned out to be the right way.

THE IMITATION GAME - TV Spot - Starring Benedict Cumberbatch, StudiocanalUK

THE IMITATION GAME - TV Spot - Starring Benedict Cumberbatch, StudiocanalUK

26. He Took On A Challenge

Back in 1939, the German naval Enigma had posed a particular problem; its indicator system was more complex than those in other services, and proved to be the most difficult to solve. Turing decided to take a crack at it, “because no one else was doing anything about it and I could have it to myself”. He may have been eccentric in his approach, but it paid off.

Royal Norwegian Navy Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Royal Norwegian Navy Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

27. He Cracked The Code

By the end of that year, Turing proved successful in cracking the German Naval Enigma. But that was just the tip of the iceberg. Not only did he solve a key component of their indicator system, but he also came up with the idea of Banburismus. Essentially, Banburismus was a method that eliminated specific sequences for the Enigma, making the process of testing settings quicker by eliminating portions of them.

28. He Met A Girl

It was also around this time that Turing met a fellow codebreaker, Joan Clarke. Turing and Clarke both worked together in Hut 8, and Clarke was the only woman to practice Banburismus—which, perhaps, was part of Turing’s admiration for her. In 1941, Turing proposed to her, and Clarke accepted. However, there was a glaring problem.

M J Richardson, Wikimedia Commons

M J Richardson, Wikimedia Commons

29. He Couldn’t Betray Himself

You see, Turing was gay. He never gave his reasoning for proposing to Clarke, though one can assume, given the pressures of the time, that he had hoped to elevate some loneliness by tying the knot with a woman he admired—not to mention one of his closest friends. Turing eventually confessed his preferences to Clarke, who reportedly had no issue with it.

However, in the end, Turing could not deny himself so completely and he opted to break off the engagement.

30. He Didn't Stop Working

While the bombe machine and his work in codebreaking were the two areas in which Turing is best remembered for, and likely had the most impact, he had more to do. He eventually wound up working at Hanslope Park for the Secret Service's Radio Security Service. Here, he came up with yet another brilliant innovation.

Thomas Nugent , Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Nugent , Wikimedia Commons

31. He Developed Another Machine

Delving even further into electronics, Turing devised another machine—a portable voice-encryption system. Its name? Delilah. However, it was made too late for anyone to use during WWII. The enemy had finally been defeated—but if Turing thought the most dangerous chapter of his life was over, he was so so wrong.

Colin Smith , Wikimedia Commons

Colin Smith , Wikimedia Commons

32. He Was Indispensable

Hugh Alexander, a codebreaker that Turing worked closely with in Hut 8 for several years, recalled Turing’s work in their hut as invaluable to the effort. To Alexander, “There should be no doubt in anyone’s mind that Turing’s work was the biggest factor in Hut 8’s success”.

He went on to remark on how much Turing changed within that hut, ultimately concluding, “It is always difficult to say that anyone is ‘indispensable’, but if anyone was indispensable to Hut 8, it was Turing”. However, due to national security, it would be years before anyone knew what went on behind closed doors.

Wim van Rossem for Anefo, Wikimedia Commons

Wim van Rossem for Anefo, Wikimedia Commons

33. He Got On With Life

The government swore everyone who worked at Bletchley Park to secrecy; even when WWII ended, and they returned to their regular lives, they were to keep mum about what they’d done. For Turing, he returned to London and worked on what he was most passionate about: math, science, and computers.

But keeping the secrets of WWII proved to be an extremely vexing endeavor.

UK Government, Wikimedia Commons

UK Government, Wikimedia Commons

34. He Couldn’t Share His Secrets

In the years between 1945 and 1947, Turing worked on the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) at the National Physical Laboratory. Turing’s work was solid, however, he couldn’t explain how he knew a computer involving human operators would work; his time at Bletchley was a secret he couldn’t share.

Becoming frustrated, he returned to Cambridge, and they made the first ACE prototype in his absence based on his work. And that wasn't all.

Philafrenzy, Wikimedia Commons

Philafrenzy, Wikimedia Commons

35. His Test Changed The World

Although the ACE prototype lent much to later computers, it is the Turing Test that has the biggest impact on modern life. Turing became interested in artificial intelligence, and theorized that if a computer could “think” like a human, to the point in which a human could not tell it was a computer, then it would be "intelligent". They created CAPTCHA tests based on the reversal of this theory.

Thomas Nugent , Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Nugent , Wikimedia Commons

36. He Met A Man

Though Turing’s professional life was undeniably rich, his personal life was a downright struggle. At the time, it was against the law to be gay in England. This would spell problems for Turing when he met a young man named Arnold Murray in 1951. They quickly dove into a secret romance—though it was far from a fairytale romance.

37. He Got Caught

Near the end of January 1952—not long after starting a relationship with Murray—someone burgled Turing’s house. In a chilling twist, Murray admitted to knowing the burglar, and Turing ultimately alerted the authorities. During the investigation, Turing admitted to having a physical relationship with Murray, and sadly, both men suffered the horrifying consequences.

Charged with “gross indecency," Turing faced trial for his so-called offense.

David Dixon , Wikimedia Commons

David Dixon , Wikimedia Commons

38. He Pled Guilty

Turing’s case went to court on March 31, 1952, and under advice from his brother and lawyer pleaded guilty. They charged Turing and gave him a devastating choice: imprisonment, or probation on the condition that he undergo hormonal injections that would, supposedly, reduce his libido. Turing took the probation—but the misery unleashed was unforgettable.

Christopher Furlong, Getty Images

Christopher Furlong, Getty Images

39. He Faced Indignity

The conditions of the probation stated that Turing would take synthetic estrogen for a year. As a result, he not only suffered from impotency, but also developed breast tissue. Turing wrote that “no doubt I shall emerge from it all a different man, but quite who I’ve not found out”. The charge also had lasting impacts on his career.

Midjourney AI, prompted by Netha Hussain, Wikimedia Commons

Midjourney AI, prompted by Netha Hussain, Wikimedia Commons

40. He Lost His Clearance

In the summer of 1951, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, two gay men, defected to the Soviet Union, taking their secrets with them. As a result, the Foreign Office became suspicious of anyone who identified as gay, believing they could possibly be a security risk. This was a major blow for Turing, who consequently lost his security clearance and could no longer work for GCHQ—the agency that had grown out of the GC&SC.

Even so, this was just the calm before the storm.

KEYSTONE Pictures USA, Wikimedia Commons

KEYSTONE Pictures USA, Wikimedia Commons

41. He Carried On

Despite this, Turing seemed to get on with his life. He retained his academic position, and although his conviction barred him from the United States, he continued to travel to European countries. During a 1952 trip to Norway, he met Kjell Carlson. But this was yet another doomed relationship.

Carleson made plans to visit Turing in England. However, when the authorities got their hands on a postcard describing these plans, they sent Carleson home before he got the chance to reunite with Turing. Everything was starting to unravel.

42. He Was Found

On the morning of June 8, 1954, Turing’s housekeeper made the most tragic discovery. Turing, it seemed, had passed during the night. Strangely, she found him in his bed, with a half-eaten apple beside him. It was this ominous apple that likely held the key to how this 41-year-old genius had met such a sudden and sad end.

Claude Richardet, Wikimedia Commons

Claude Richardet, Wikimedia Commons

43. He Poisoned His Apple

Officials performed an autopsy, which came to the conclusion that the official cause of Turing's demise was cyanide poisoning. Because of the position of the apple, many assumed it held the poison, and that Turing had likely injected it with a fatal dose before consuming it.

However, as fate would have it, the apple was never properly tested for cyanide. Turing's brother, who identified his body, was pressured into accepting the verdict of the coroner's inquest. The conclusion was that Turing had taken his own life—but not everyone agreed.

44. He Didn’t Do It?

Turing's mother took the news of her son's passing as one might expect—with grief and insurmountable heartbreak. She also vehemently refused to accept that he had died by suicide. Instead, she believed that he had simply been careless with his chemicals. But there is also a darker side to this theory.

One of his biographers claimed that Turing may have intentionally staged his demise to appear like an accident, thereby sparing his mother's feelings. However, some have other theories.

45. He May Have Been Careless

The main argument against Turing’s passing being intentional is that he did not appear depressed leading up to it. Despite his court ruling, he appeared to handle it "with good humour". He also seemed to be planning for the future, having made to-do lists. One philosopher even wondered if Turing inhaled the cyanide by accident from a device he had set up nearby.

Sadly, the entire truth will never be fully laid out—but what is known is that the world lost an incredible force of a person.

46. He Deserved An Apology

Although it would take 50 years after his passing, the injustice of Turing’s imprisonment did not go unacknowledged. In August 2009, John Graham-Cumming, a British programmer, started a petition to force the government to apologize for the charge. It received more than 30,000 signatures, a demand that proved difficult for the government to ignore.

John Graham-Cumming at WebSummit: Making security simple, Cloudflare

John Graham-Cumming at WebSummit: Making security simple, Cloudflare

47. He Got An Apology

Only months later, the prime minister at the time, Gordon Brown, issued a statement about the petition—even calling Turing’s treatment “appalling”. That, however, wasn’t enough. At the end of 2011, William Jones and John Leech created another petition, this time demanding the government pardon Turing for his conviction.

the International Monetary Fund, Wikimedia Commons

the International Monetary Fund, Wikimedia Commons

48. He Deserved More

In the request that they made for the pardon, they wrote “Alan Turing was driven to a terrible despair and early death by the nation he'd done so much to save. This remains a shame on the British government and British history”. Despite this, there remained opposition to the pardon in the parliament.

William Jones on the Alan Turing pardon, Quays TV

William Jones on the Alan Turing pardon, Quays TV

49. He Knew What He Was Doing

Then Justice Minister, Lord McNally, did not think that it was appropriate to pardon Turing. In McNally’s view, “A posthumous pardon was not considered appropriate as Alan Turing was properly convicted of what at the time was a criminal offense. He would have known that his offense was against the law and that he would be prosecuted”. This did not discourage Leech.

Chris McAndrew, Wikimedia Commons

Chris McAndrew, Wikimedia Commons

50. He Got A Pardon

Leech continued to lead a campaign to secure Turing a pardon. It was a public campaign that gained the attention of many notable people, including Stephen Hawking. Leech leaned on the fact that Turing was a hero, and called the entire situation embarrassing for the government. After much red tape, Elizabeth II signed a pardon for Turing in December 2013.

Photograph taken by Julian Calder for Governor-General of New Zealand, Wikimedia Commons

Photograph taken by Julian Calder for Governor-General of New Zealand, Wikimedia Commons

51. He Was A Hero

Despite his unfortunate treatment by the government, not to mention his tragic end, Alan Turing was a hero of not just Britain, but the entire world. While it’s impossible to now say what the outcome of WWII would’ve been without him, most estimate that his work helped shorten it by years, saving millions of lives.

The world would have been a very different place without Alan Turing, and his memory lives on for all who follow in his footsteps.

You May Also Like:

The Truth About America’s Most Honorable Founding Father

The Life and Legacy Of A Peaceful Revolutionary