Intelligence Against Tyranny

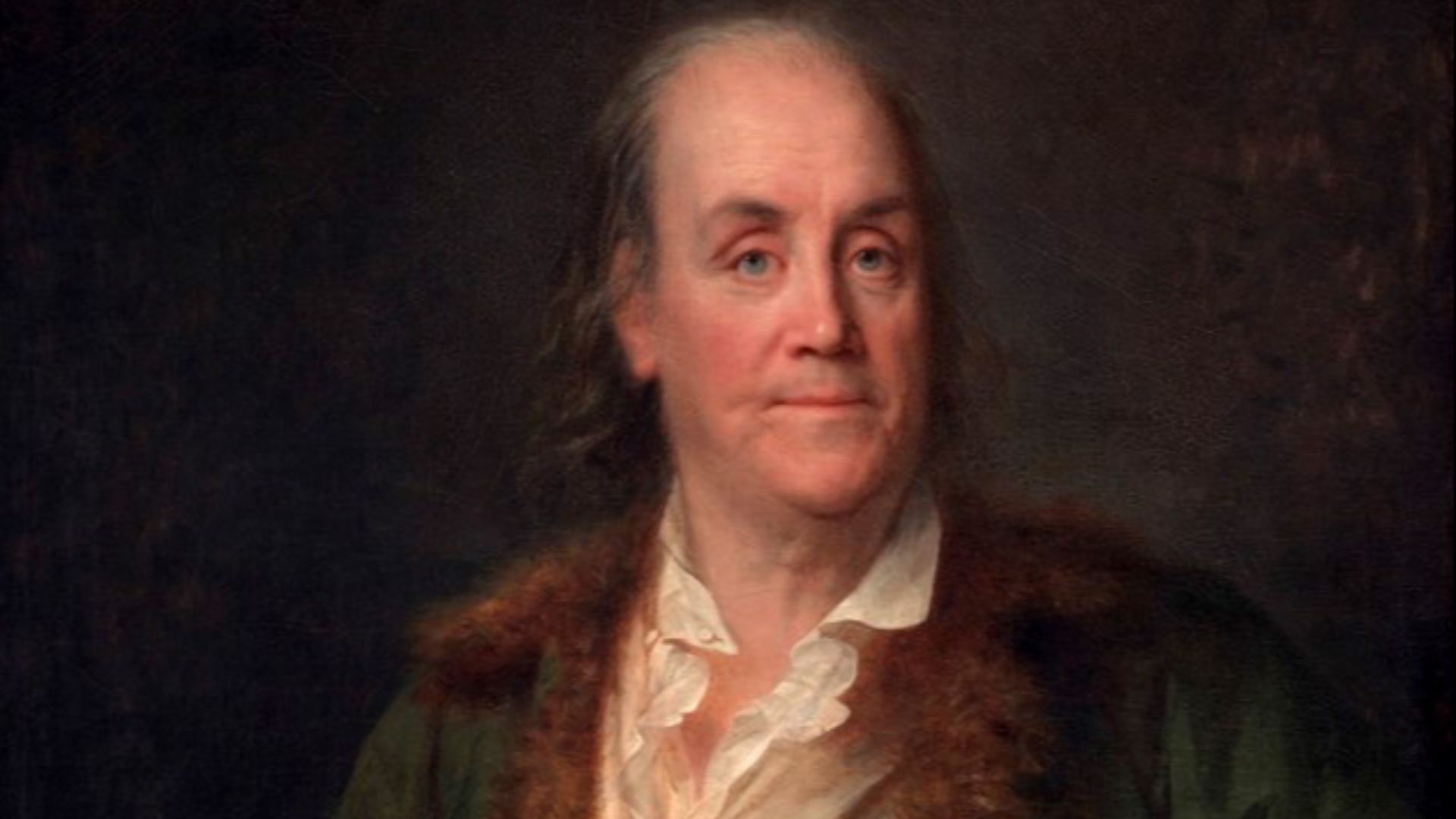

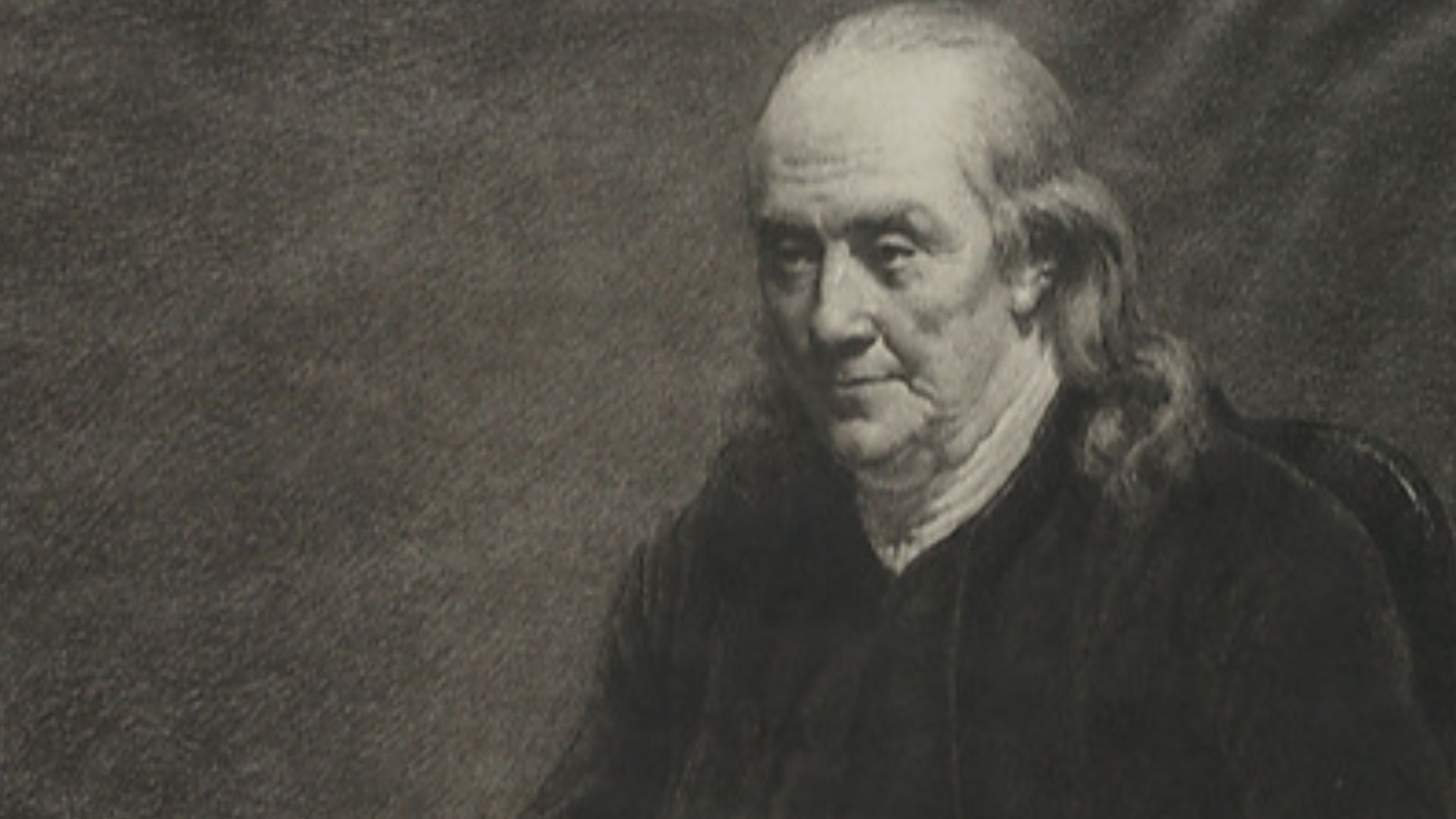

Although never completing a formal education, Benjamin Franklin constantly learned about everything he could, using his natural wisdom to make waves in colonial America. Not only did he regularly show his intelligence and ingenuity in his studies and experiments, but also an unyielding courage in establishing US independence. The mix of these qualities made him possibly the most respected Founding Father—even in his time.

1. He Was A Natural Leader

Although Benjamin Franklin never ran for president, no one could ever say he lacked the necessary qualities for strong leadership. In fact, these qualities came naturally to him and were on display from an early age. Having been born on January 17, 1706, in Boston, Province of Massachusetts Bay, Franklin grew up surrounded by those who looked up to him—as he would later state, he had been "generally the leader among the boys".

Still, he didn’t have complete control of his life.

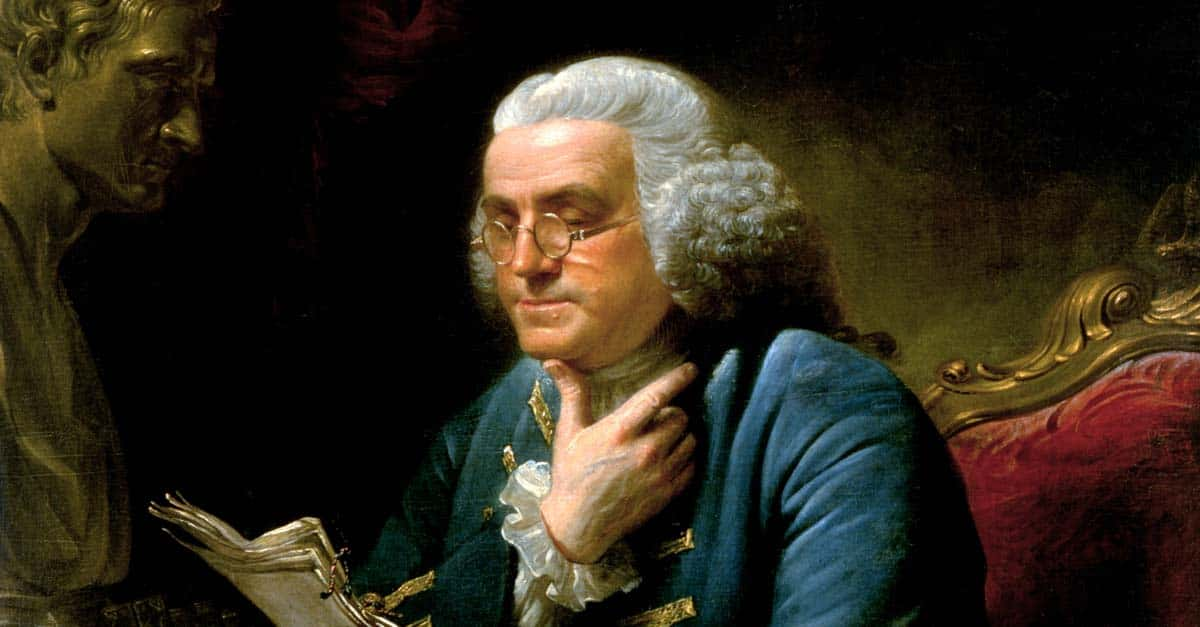

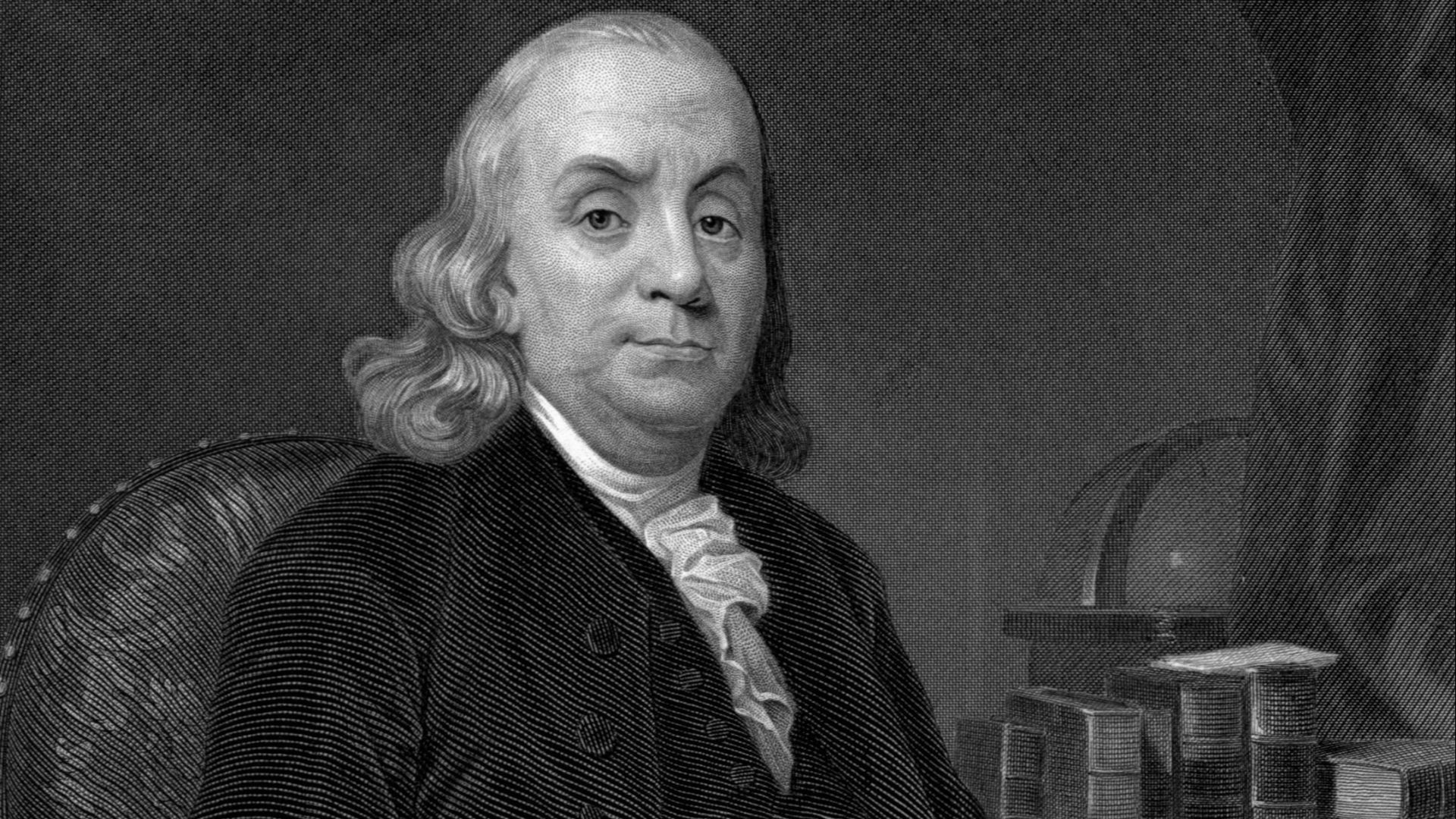

Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Wikimedia Commons

Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Wikimedia Commons

2. He Quit School

Franklin's family wasn’t privileged by any means, and as the 10th out of his parents’ eventual 17 children, he didn’t receive much help. So, although his parents wanted him to go to school and possibly pursue a career in the church, they only had enough money for two years of education until he turned 10. Even so, he never stopped teaching himself.

Of course, he wasn’t without opportunity.

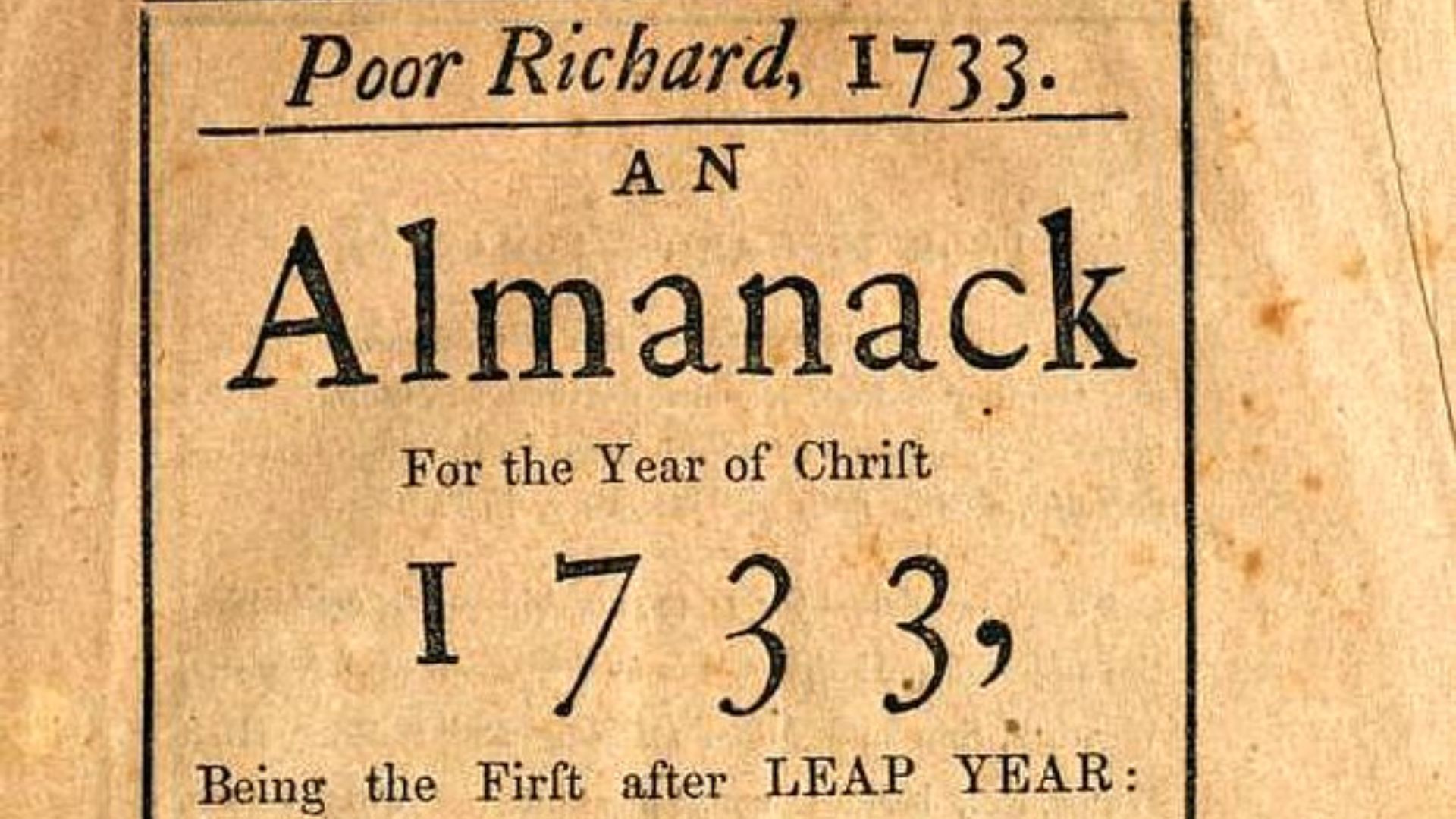

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

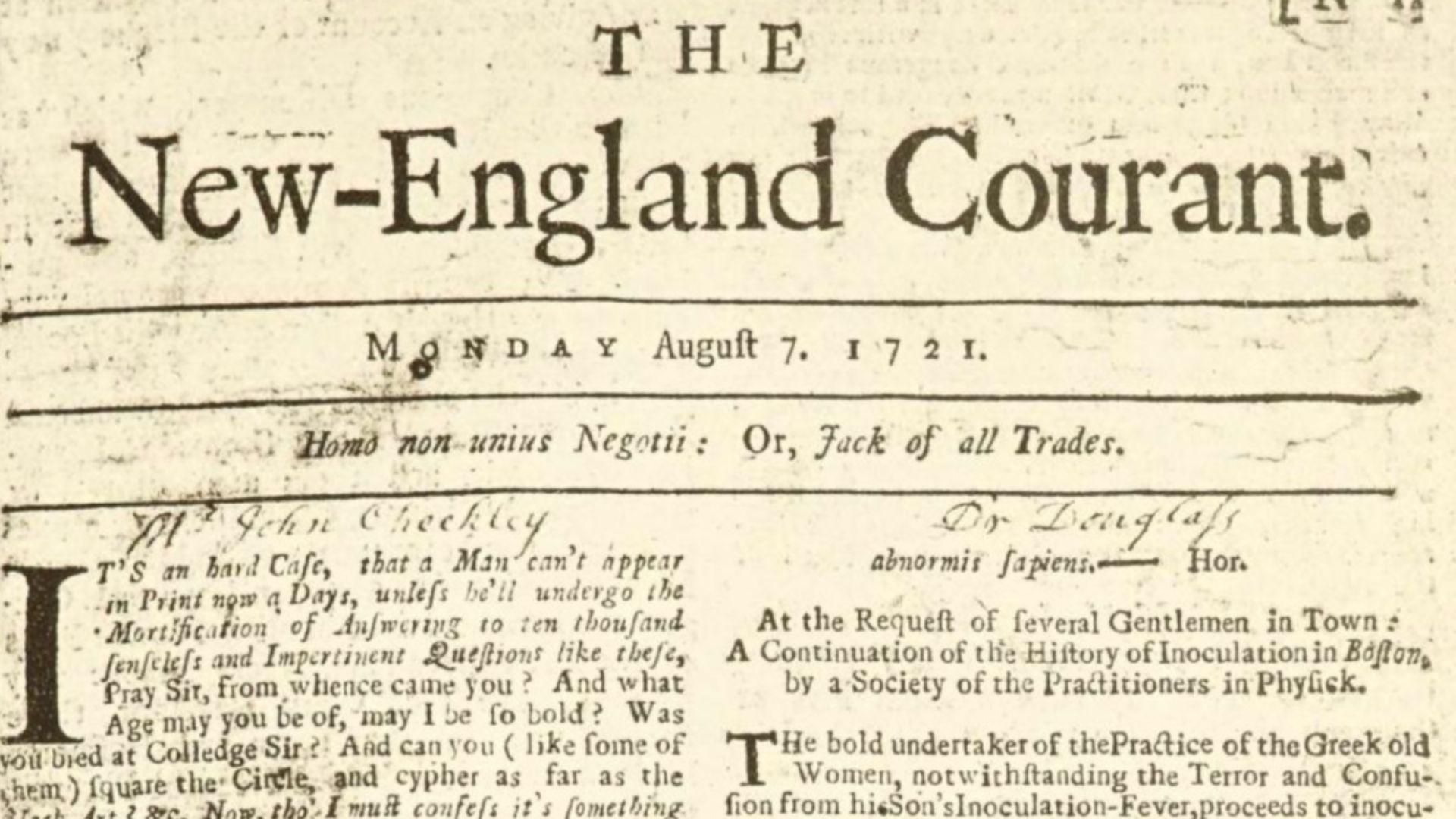

3. His Brother Started A Company

His first couple of years out of formal schooling, Benjamin Franklin found work mostly with his brother, James, who took Benjamin on as an apprentice in printing. In 1721, James opened Boston’s third local newspaper called The New-England Courant, and the teenage Benjamin continued to study intently.

However, his brother didn’t let him do everything.

New England Courant, August 7, 1721, Wikimedia Commons

New England Courant, August 7, 1721, Wikimedia Commons

4. He Wrote In Secret

Being his brother’s apprentice, Benjamin grew disappointed that James refused to publish any of his writings. Therefore, under the pseudonym of “Silence Dogood,” Benjamin wrote to James’ paper every two weeks with entertaining pieces, pretending to be a middle-aged widow. None the wiser, James published 14 of these letters before learning the truth.

Needless to say, Benjamin Franklin wasn’t afraid of saying what he wanted.

5. He Spoke Out

A year after founding his paper, James wrote a negative piece about the governor of Massachusetts, Samuel Shute, and paid the price for it. Incarcerated for several weeks, James left the paper for Benjamin to run, who used his pseudonym to protest the situation, stating that there was “no such thing as public liberty without freedom of speech".

Following this rebellious act, Benjamin knew he couldn’t stay.

6. He Went On The Run

James served his time and gained his freedom, but the authorities banned him from publishing his paper under his name, so Benjamin legally became the publisher. James kept this a secret from the public, so even when Benjamin broke the law by leaving the apprenticeship after a fight between the two, he knew James wouldn’t raise the alarm.

Soon after this, he met someone special.

Charles E. Mills, Wikimedia Commons

Charles E. Mills, Wikimedia Commons

7. He Popped The Question

Effectively leaving his early life behind, Benjamin Franklin traveled to Philadelphia and continued his work in printing, at one point staying as a boarder in the home of John and Sarah Read. There, he met Deborah, their daughter, who was two years his younger. The two instantly connected, and Franklin asked her to marry him—only for her mother to refuse the request.

Unfortunately, she had to move on.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

8. She Found Someone Else

In refusing Franklin, Deborah Read’s mother cited his uncertain finances and imminent departure for London. Unable to convince her otherwise, Franklin left for London, and in his absence, Deborah's mother had her marry a craftsman named John Rogers. This proved the worse choice, as Rogers quickly spent her dowry and ran off to Barbados.

Fortunately, Benjamin Franklin was on his way.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

9. He Came Back

Rumors spread that John Rogers had perished, but with nothing confirmed, Deborah couldn’t legally remarry. Therefore, when Franklin returned in 1726 and they picked up their relationship, they decided to enter a common-law marriage four years later. Not only that, but Deborah agreed to raise an illegitimate son of his who had been born in the previous years.

Around this time, Franklin also developed a set of guidelines for himself.

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

10. He Followed A Code

Around the time of his return to Philadelphia, the 20-year-old Benjamin Franklin had given great thought to what kind of person he wanted to be. Desiring to improve himself constantly, he came up with 13 virtues that he believed would nurture his integrity. These included more practical things like cleanliness and frugality, as well as idealistic concepts like temperance.

Being such a thoughtful man, he tried to find like-minded people.

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

11. He Formed A Community

During his time in London, Franklin became acquainted with English coffeehouses, and the contemplative discussions often held within. Wanting to bring that kind of philosophical conversation to the colonies, he established the “Junto” group in 1727, bringing members together to talk over current events and how they could improve the world.

All the while, he continued his work in printing.

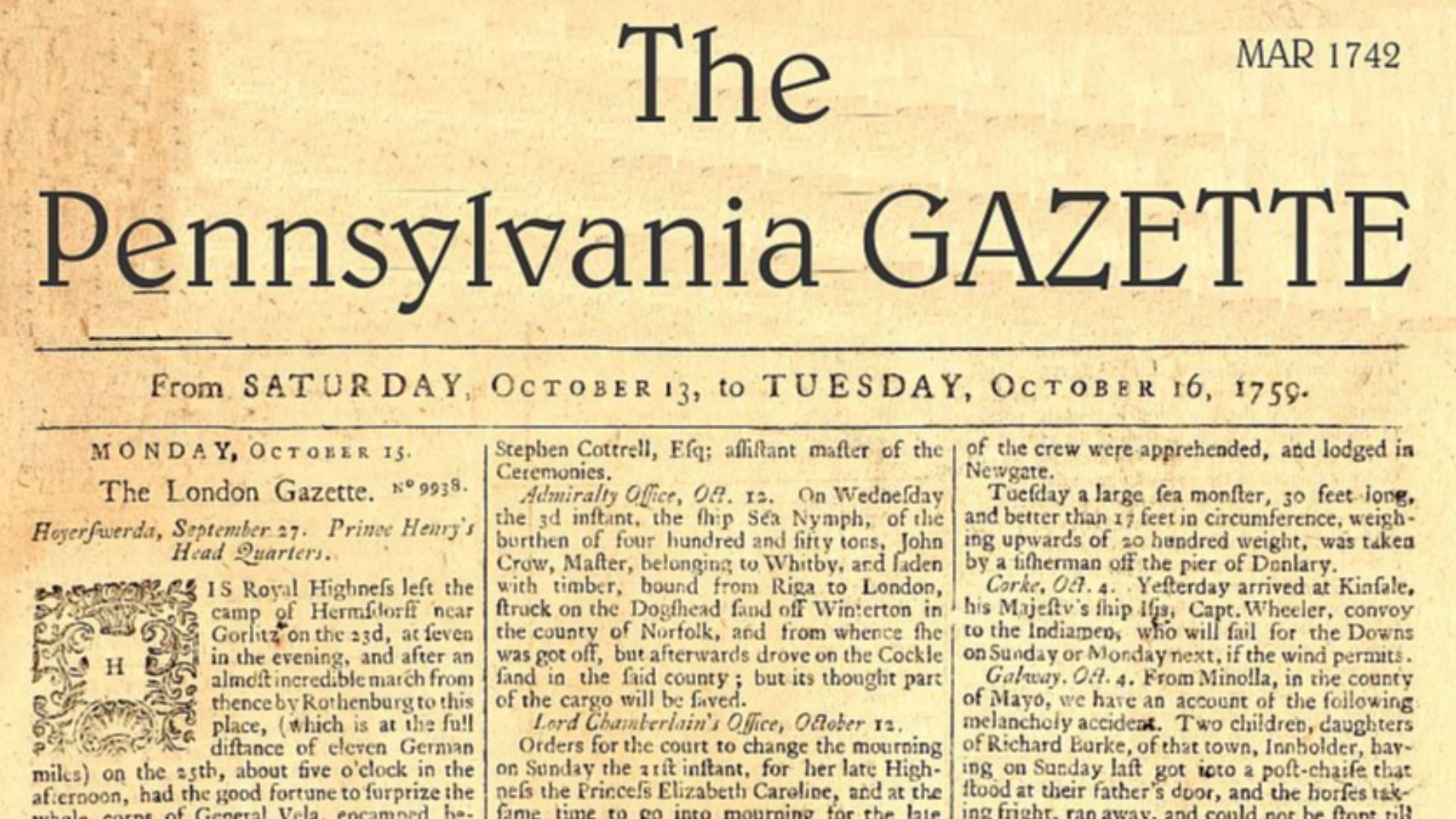

12. They Looked Up To Him

Two years later, Franklin found himself in a position to speak his mind and influence others, but without using a fake identity. Taking the helm of publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette, he freely and regularly expressed his commentary on everyday issues, garnering no small amount of admiration from his readers.

This line of work came from a distinct sense of purpose.

William Goddard, founder, printer and publisher, Wikimedia Commons

William Goddard, founder, printer and publisher, Wikimedia Commons

13. He Felt Called

According to experts, Franklin's draw to this kind of social commentary went beyond a passion for journalism, as he felt a divine responsibility. Franklin believed that, despite his personal shortcomings, he understood better than most what it meant to be morally good. Due to this, he felt it his duty to educate his readers on how to live their best lives.

Although he didn’t need to, he assumed another identity.

David Martin, Wikimedia Commons

David Martin, Wikimedia Commons

14. He Took Another Name

In the early 1730s, Benjamin Franklin began another publication called the Poor Richard's Almanack, writing the regular issues under the identity of “Richard Saunders”. This seemed to be more out of fun than anything, as everyone knew Benjamin was the author, especially since his style was so recognizable.

Luckily, this worked out for him.

Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Wikimedia Commons

Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Wikimedia Commons

15. He Was Successful

Releasing his first issue of the Poor Richard’s Almanack in 1733, the publication became an instant phenomenon, and many consider it his most successful work. In these issues, Franklin offered several pieces of wisdom labeled as “Poor Richard’s Proverbs”, which remain popular to this day, and each year, he sold around 10,000 copies.

As his reputation grew, he got the attention of some shadowy individuals.

Benjamin Franklin, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Franklin, Wikimedia Commons

16. He Joined A Secret Society

Also in the early 1730s, his growing prominence granted him admission to the world’s oldest secular fraternity, the Freemasons. Joining in 1730 or 1731, he went through initiation into Philadelphia’s Masonic lodge, but only took a few years to rise through the ranks. By 1734, he took the position of Grand Master.

He used this influence to create more helpful organizations.

William Perkins Babcock, Wikimedia Commons

William Perkins Babcock, Wikimedia Commons

17. He Fought Fires

To his credit, Benjamin Franklin spent much of his life backing up all his ideas on virtues and morals with actual action, doing what he could to give back to the people. Being one of the first of its kind in the colonies, he established a volunteer firefighting department called the Union Fire Company in 1736.

Meanwhile, he just kept getting busier.

Jan Arkesteijn, Wikimedia Commons

Jan Arkesteijn, Wikimedia Commons

18. He Was Chosen

Due to his years of publishing and printing experience, Franklin received an offer to take the position of postmaster of Philadelphia, which he happily accepted in 1737. Taking charge of all mail between Pennsylvania and the northern and eastern colonies, he held this position for the next 16 years.

Soon after, he got his first taste of scandal and public scrutiny after a horrifying incident with the Freemasons—but we'll get to the chilling details of that later.

Photo Researchers, Getty Images

Photo Researchers, Getty Images

19. He Wanted To Help

As the 1740s came along, like his Junto group, Franklin sought to create a community that allowed men of learning to come together. This idea developed into the American Philosophical Society, established in 1743, which created a space for these men to discuss their projects and ideas.

On his own, he also delved into scientific experimentation.

Eric Kilby from Somerville, MA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Eric Kilby from Somerville, MA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

20. He Was Fascinated

In Franklin’s constant pursuit of learning, he attended a lecture held by Archibald Spencer, during which he witnessed firsthand the effect of static electricity. Inspired by this, he began his experiments in electricity, during which he became the first to not only recognize the true nature of positive and negative charges but also to label them as such.

This led to one of his greatest inventions.

Le Roy C. Cooley, Wikimedia Commons

Le Roy C. Cooley, Wikimedia Commons

21. He Built A Battery

Toward the end of the 1740s, Benjamin Franklin’s research into electricity brought him to the forefront of understanding the phenomenon, as evidenced by his project in 1748. That year, he used a collection of lead plates, wires, silk cords, and 11 glass panes to create what he referred to as an “electrical battery,” but was actually a multiple plate capacitor.

Of course, he wasn’t all brains.

Flickr: Adam Cooperstein, Wikimedia Commons

Flickr: Adam Cooperstein, Wikimedia Commons

22. He Fought Back

In 1744, more fighting came to North America as conflict escalated between Britain and France, sweeping the colonies up in it. As for Philadelphia, Franklin grew concerned for its defense, especially since all of the city’s legislators refused to take action. Taking the duty for himself, Franklin formed his own militia called the Association for General Defense.

Meanwhile, he took an interest in a different kind of battlefield.

23. He Played The Game

Likely unimpressed by those already in governing seats, Benjamin Franklin entered the political landscape of Philadelphia and took it by storm. By the end of the 1740s, he had become a councilman and justice of the peace, making the switch to a position in the Pennsylvania Assembly by 1751.

This gave him the power to make bigger changes.

after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Wikimedia Commons

after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Wikimedia Commons

24. He Reformed Education

While Franklin hadn’t received much formal education, he still advocated for it. From 1750 to 1753, he and educators William Smith and Samuel Johnson created a new style of college education to replace the current one. This emphasized dividing content among several specialized professors instead of one, and would be in English instead of Latin.

During this time, Franklin made one of his most significant discoveries.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

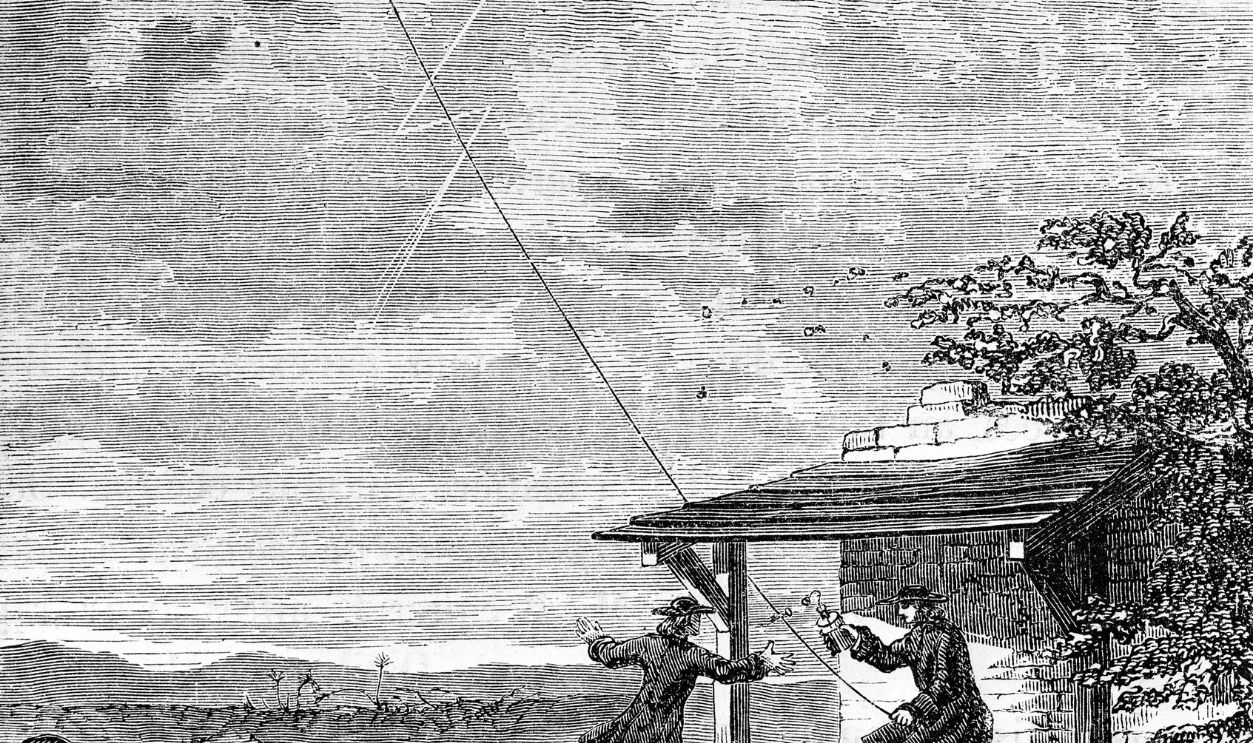

25. He Thought Of A Test

Only a couple of years prior, the idea that lightning consisted of electricity was only a theory, but Benjamin Franklin aimed to change that in 1752. Believing he could prove this, he developed an experiment using a kite flown in a storm. That May, instead of a kite, Thomas-François Dalibard (a physicist and friend of Franklin’s) held up a 40-foot-tall iron rod that successfully drew out electrical sparks.

Still, Franklin wasn’t going to let Dalibard have all the fun.

26. He Flew His Kite

A month after Dalibard’s experiment, it’s believed Benjamin Franklin ran it himself, despite him later reporting it being done by someone unnamed. With his son William, Benjamin tied a kite to a Leyden jar—which could store an electrical charge—using wet hemp string and attached a house key to it, flying it through a storm and successfully producing an electric spark.

Scientists from all over the world took notice.

27. He Inspired Others

When Benjamin Franklin conducted his experiment, he took several safety precautions, such as standing on an insulator and using a nonconductive string to steer the kite. However, as word spread of his breakthrough in the following months and others tried to replicate it, people like Russian physicist Georg Wilhelm Richmann ended up electrocuting themselves.

Outside of scientific achievements, he still influenced the world around him.

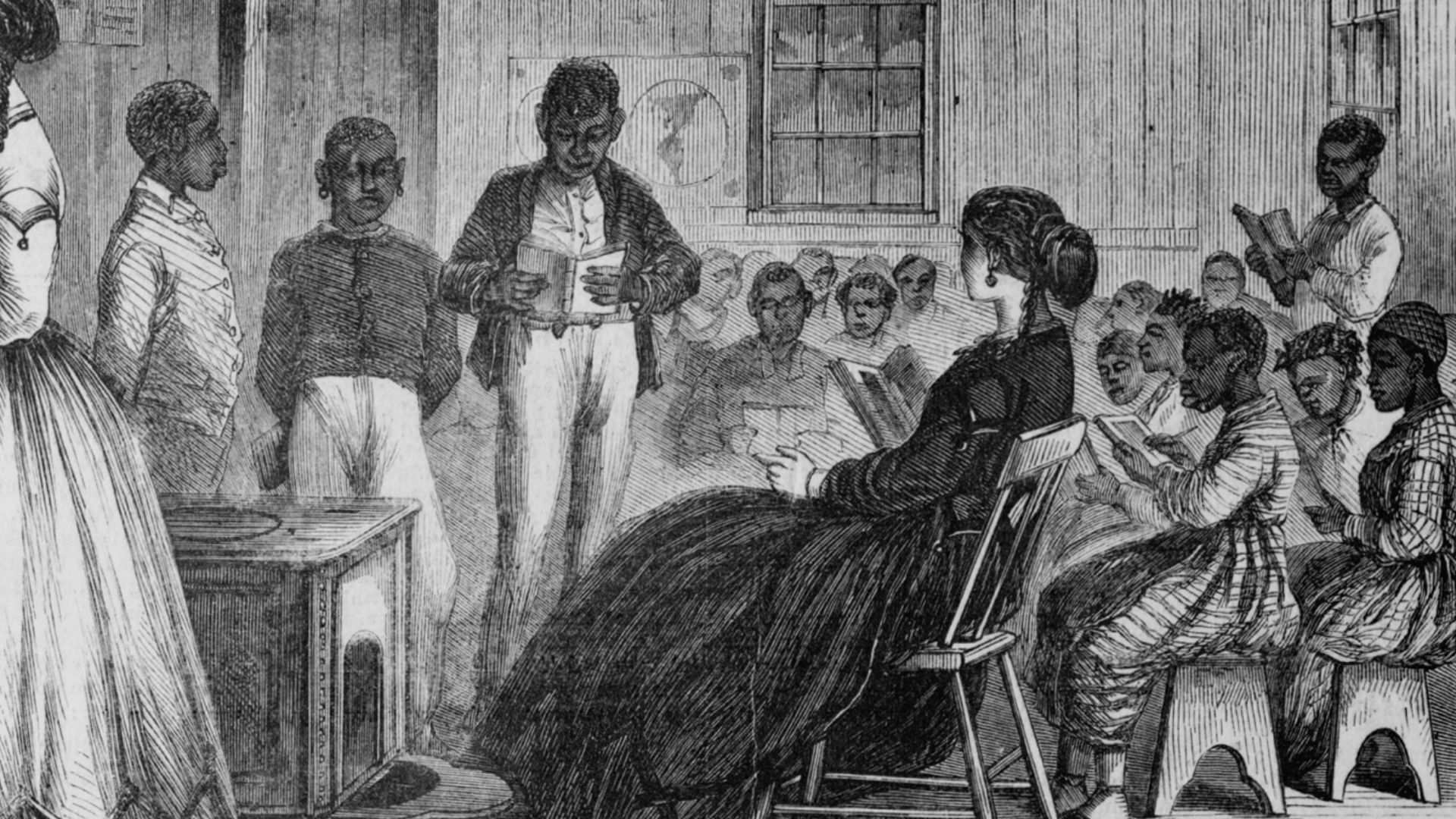

28. He Pushed For Change

For years, Franklin was complicit in furthering the slave trade, both in owning slaves himself and promoting the sale of slaves in his paper. However, by 1758, he experienced a shift in his perspective and began criticizing the whole system. Additionally, he supported causes introduced to help slaves in Philadelphia, such as giving them a formal education.

Meanwhile, he had other duties to attend to.

Jas. E. Taylor., Wikimedia Commons

Jas. E. Taylor., Wikimedia Commons

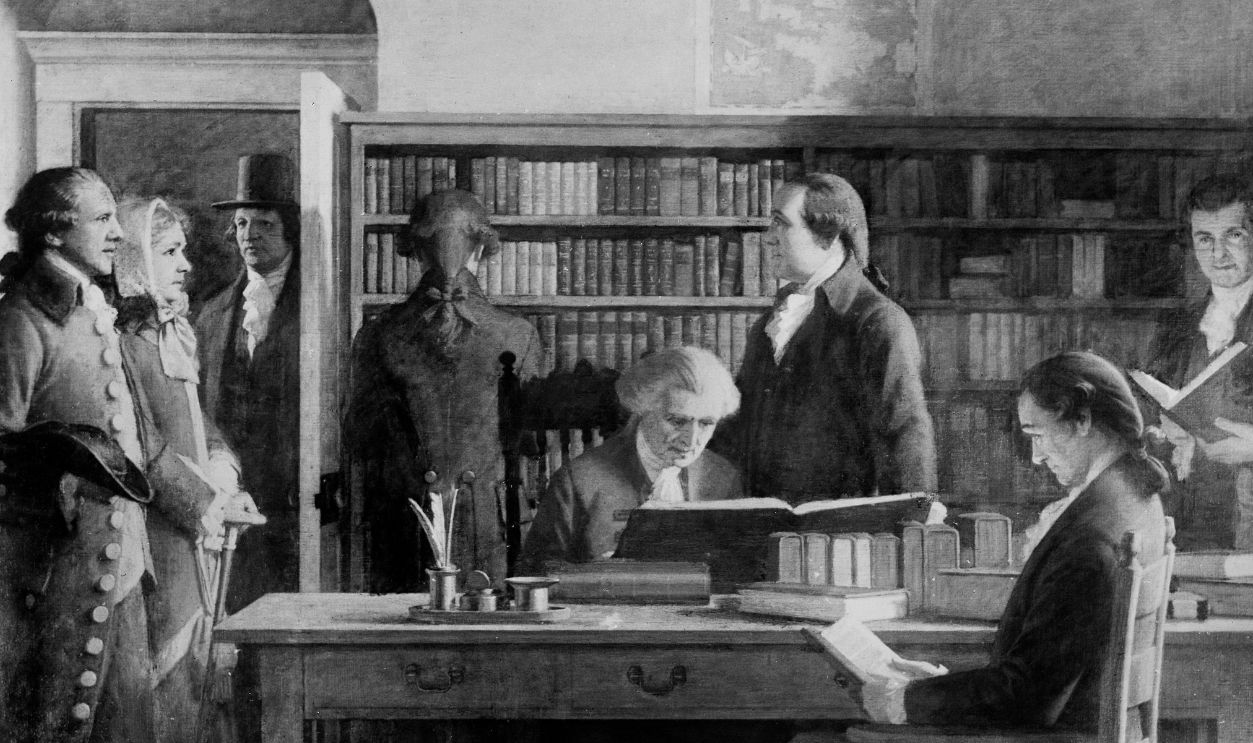

29. They Sent Him Overseas

At this time, Pennsylvania was a proprietary colony under the authority of the Penn family, but the people weren’t happy. In 1757, the Pennsylvania Assembly tasked Franklin with traveling to Britain and protesting the amount of power the Penn family held. Unfortunately, he couldn’t garner enough support and had to return unsuccessfully to America.

Furthermore, he made other issues worse.

Arthur Devis, Wikimedia Commons

Arthur Devis, Wikimedia Commons

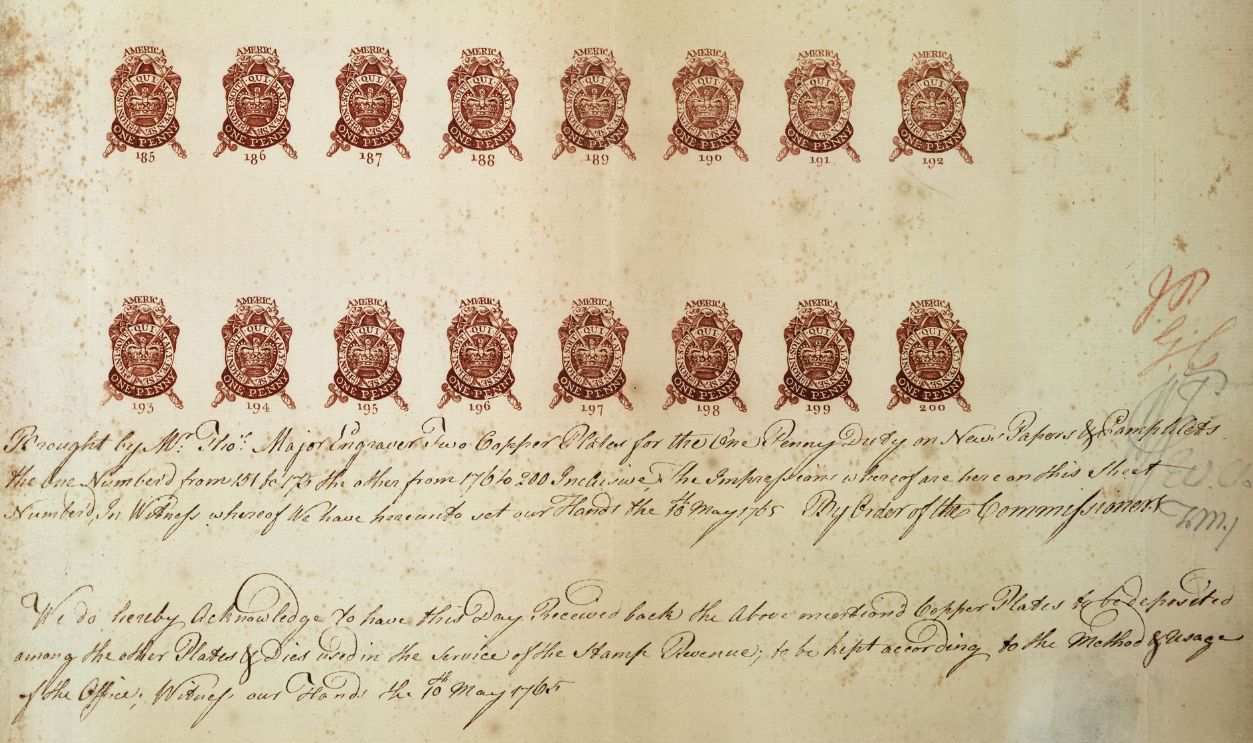

30. They Hated Him

During another London trip, Franklin learned of the incoming 1765 Stamp Act, and seeing that it amounted to colonial taxation without consent, he attempted to halt its passage. Failing this, he tried to ease the outcome by appointing a friend of his as Pennsylvania’s stamp distributor, but this only led the colonists to believe he had always supported the act.

Not one to be too prideful, he listened to their complaints.

Board of Stamps, Wikimedia Commons

Board of Stamps, Wikimedia Commons

31. He Listened To Them

Back home, the colonists in Pennsylvania weren’t quiet about their anger toward Benjamin Franklin and even threatened to tear down his house. Listening to their criticisms, Franklin's vigor renewed, and he testified against the Stamp Act during the proceedings at the House of Commons, ultimately getting his point across and the act repealed.

Naturally, he wasn’t done speaking out.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

32. He Called Them Out

Franklin's enlightened views on racial injustice also extended to the treatment of Indigenous people by the colonists. When a group of settlers called the Paxton Boys wiped out a peaceful group of Susquehannock people and marched on Philadelphia, Franklin formed a militia and sent the settlers away, later writing a critical rebuke of their actions.

Suddenly, he was off on another adventure.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

33. He Traveled Europe

These London trips continued over the next two decades, and weren’t always occupied by official business. Basing himself in London, Franklin and his son traveled many times on smaller trips to other spots in England, as well as bigger adventures to places like Lichfield and Edinburgh, the latter of which he considered possibly the happiest weeks of his life.

He also spent his time creating problems for the British.

Tilmandralle, Wikimedia Commons

Tilmandralle, Wikimedia Commons

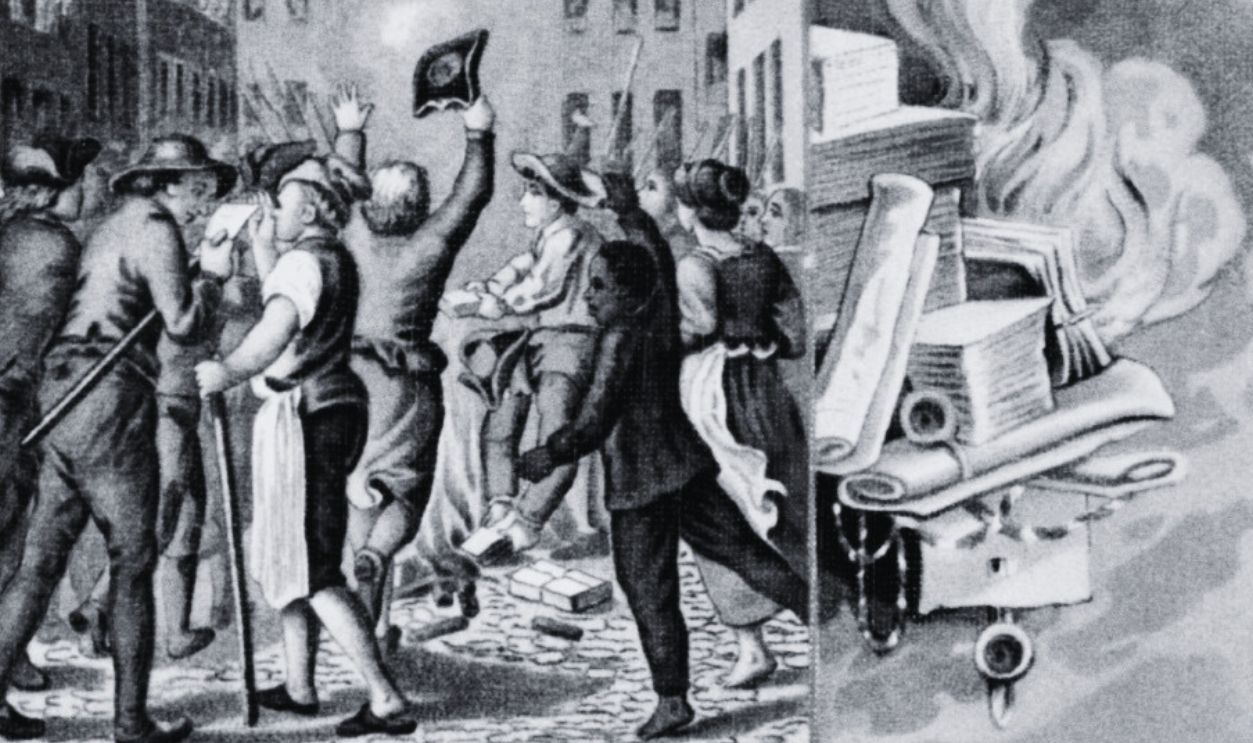

34. He Stirred The Pot

By the early 1770s, Benjamin Franklin’s reputation in Britain had grown, but not always in a good way. In one instance, he found private letters proving that Massachusetts’ governor and lieutenant governor had pushed Britain to come down harder on the colony. Franklin sent these letters home, which were soon leaked to the Boston Gazette.

Also around this time, he came up with another well-known concept.

Boston Gazette, Wikimedia Commons

Boston Gazette, Wikimedia Commons

35. He Influenced Decision-Making

Some of Benjamin Franklin’s most significant inventions weren’t immediately celebrated, but have still stuck around. In 1772, he wrote a letter to Joseph Priestley, wherein he outlined his way of making decisions with a chart of two columns—one representing good points and the other bad. This became the first known use of a “Pros and Cons List,” and he even called it such.

Unfortunately, this time of happiness and excitement would soon give way to tragedy.

Rosalie Filleul, Wikimedia Commons

Rosalie Filleul, Wikimedia Commons

36. He Lost Her

Benjamin and Deborah Franklin’s marriage may have been pleasant, but his constant travel overseas strained their relationship, especially since her fear of the ocean kept her from joining him. Sadly, even when she wrote to him of her illness in 1769, business forced him to remain in Britain till 1775, the year after she had passed from a stroke.

This horrible loss wasn’t the only thing he missed, however.

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

37. He Got Back Just After

Upon Benjamin Franklin’s return in 1775, he entered a whole new landscape, as the Battles of Lexington and Concord occurred only a month before he got home. Although this meant he had effectively missed the beginning of the American Revolution, decades of dealing with the British and the qualms of the colonists made him eager to help.

All of his efforts and goodwill earned him an important position.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

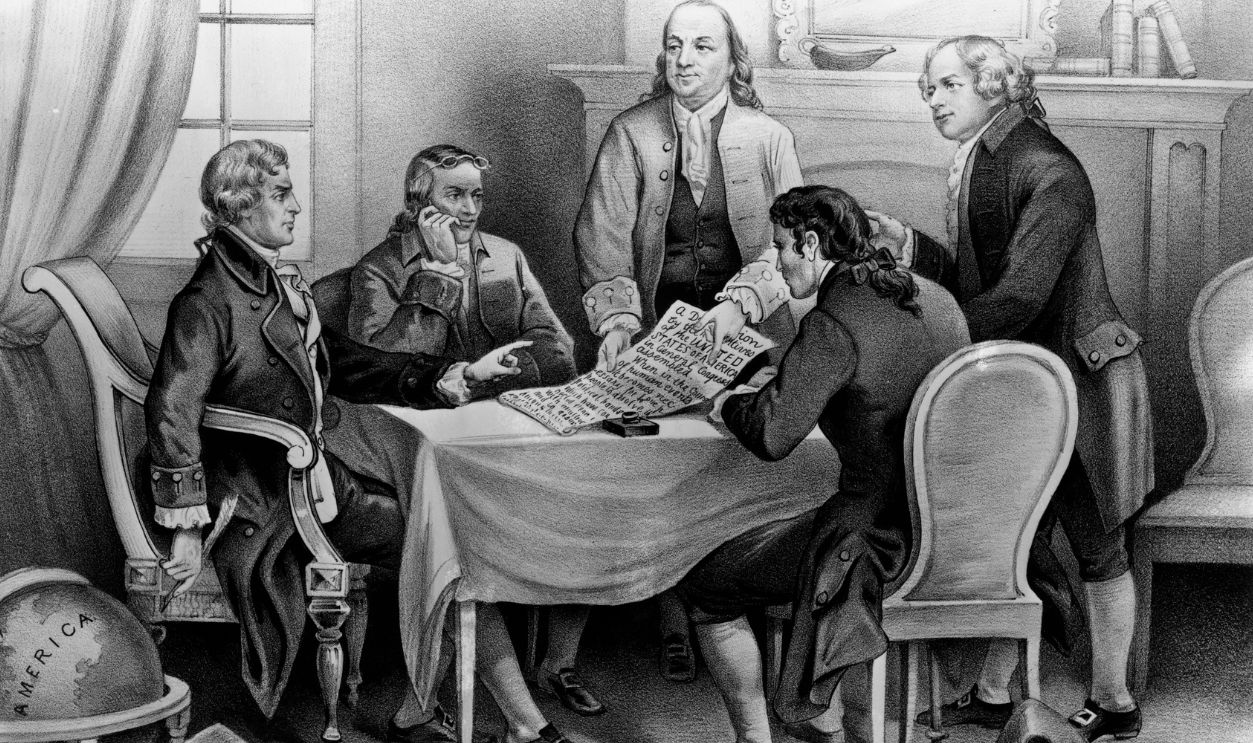

38. They Chose Him

For all he did in pursuit of the colony’s betterment, the Pennsylvania Assembly appointed Franklin as their delegate to the brand-new Second Continental Congress. Not only that, but after he and the other delegates decided to draft the Declaration of Independence a year later, they chose him to be on the Committee of Five as an author.

However, he wasn’t the most present member.

John Trumbull, Wikimedia Commons

John Trumbull, Wikimedia Commons

39. He Couldn’t Attend

Benjamin Franklin maintained his position on the Committee of Five, but a nasty case of gout stopped him from regularly appearing at meetings. Nonetheless, he gave what input he could, and after receiving Thomas Jefferson’s first draft of the Declaration, he offered only a few tiny changes—which he still insisted were important.

Of course, it wasn’t long before he was back across the ocean.

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, Wikimedia Commons

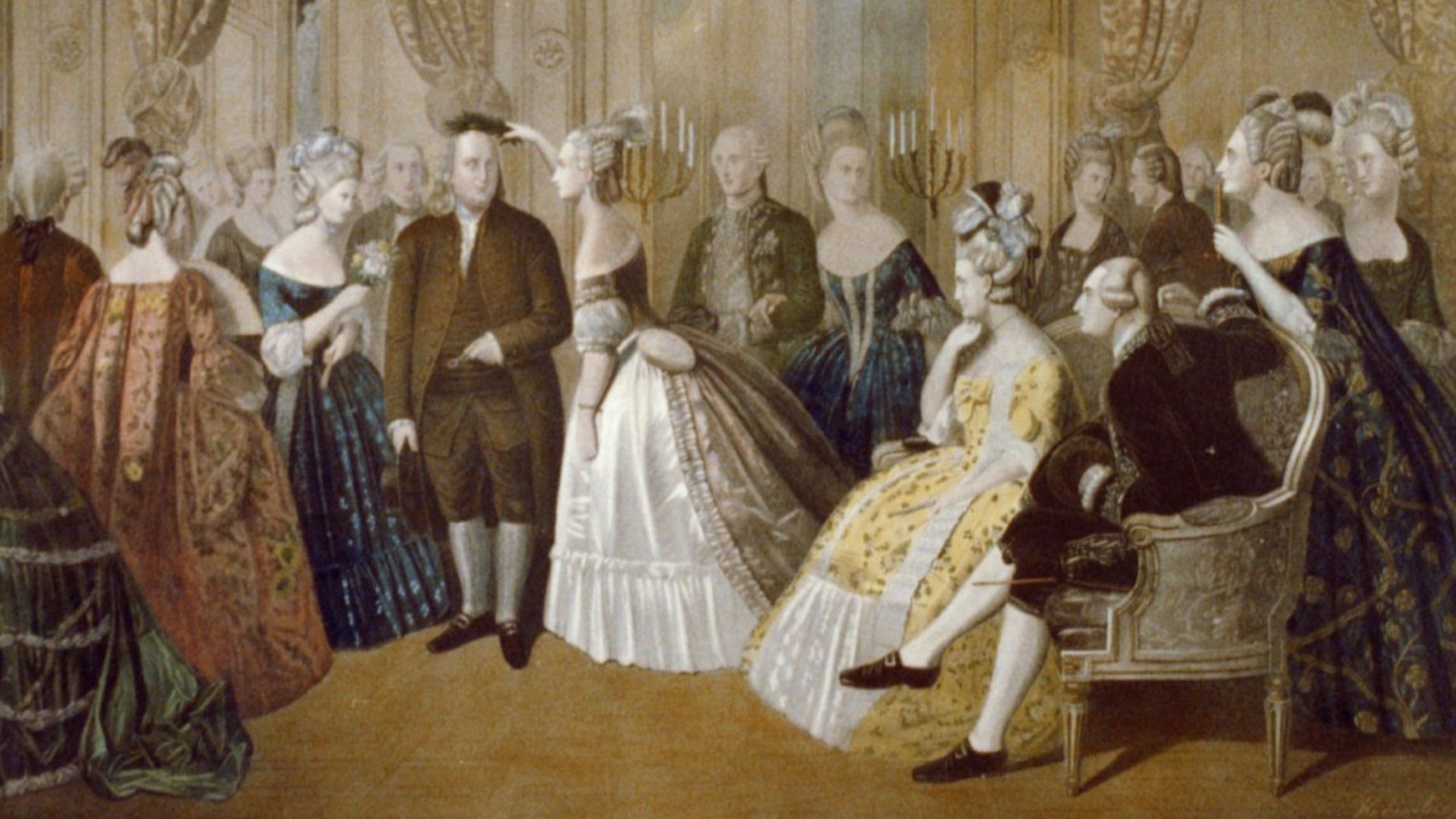

40. He Went On Another Adventure

In late 1776, Congress tasked Franklin with once again traveling to Europe on behalf of America, but this time to France. Taking his son William with him again, he worked tirelessly to represent the US’s interests in the Revolution, including negotiating an alliance with France’s armies.

Even in France, he didn’t stop trying to make a societal difference.

Hohenstein, Anton, 1823-1909, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Hohenstein, Anton, 1823-1909, artist, Wikimedia Commons

41. He Was Tolerant

Although he was in France with official business, Franklin couldn’t help but continue his work to improve the virtues of those around him. He often had lengthy discussions with other thinkers, usually promoting religious tolerance and indirectly influencing the King’s eventual Edict of Versailles, which allowed non-Catholics to practice their faiths freely.

Back home, he only rose higher on the political chain.

George Peter Alexander Healy, Wikimedia Commons

George Peter Alexander Healy, Wikimedia Commons

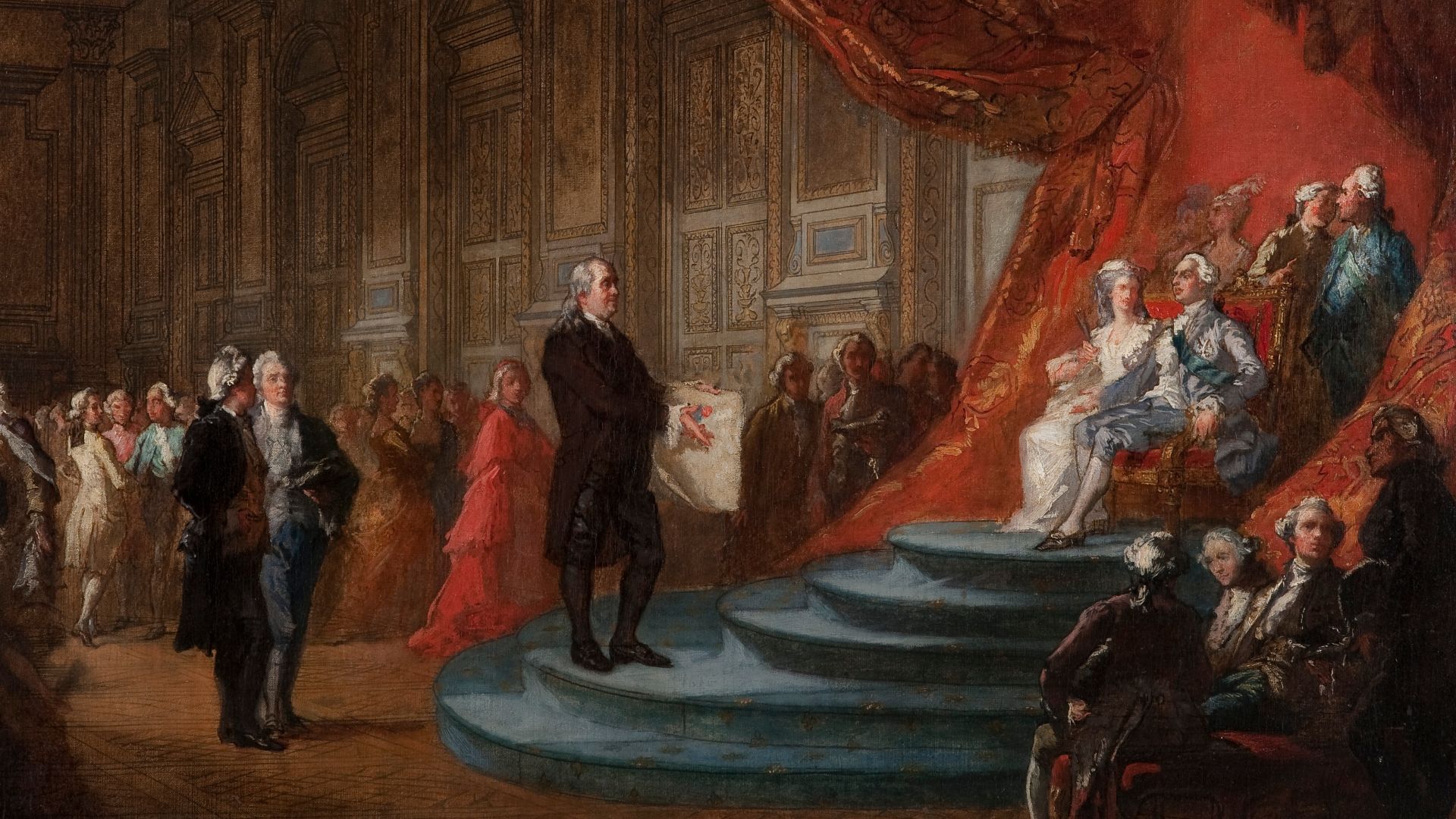

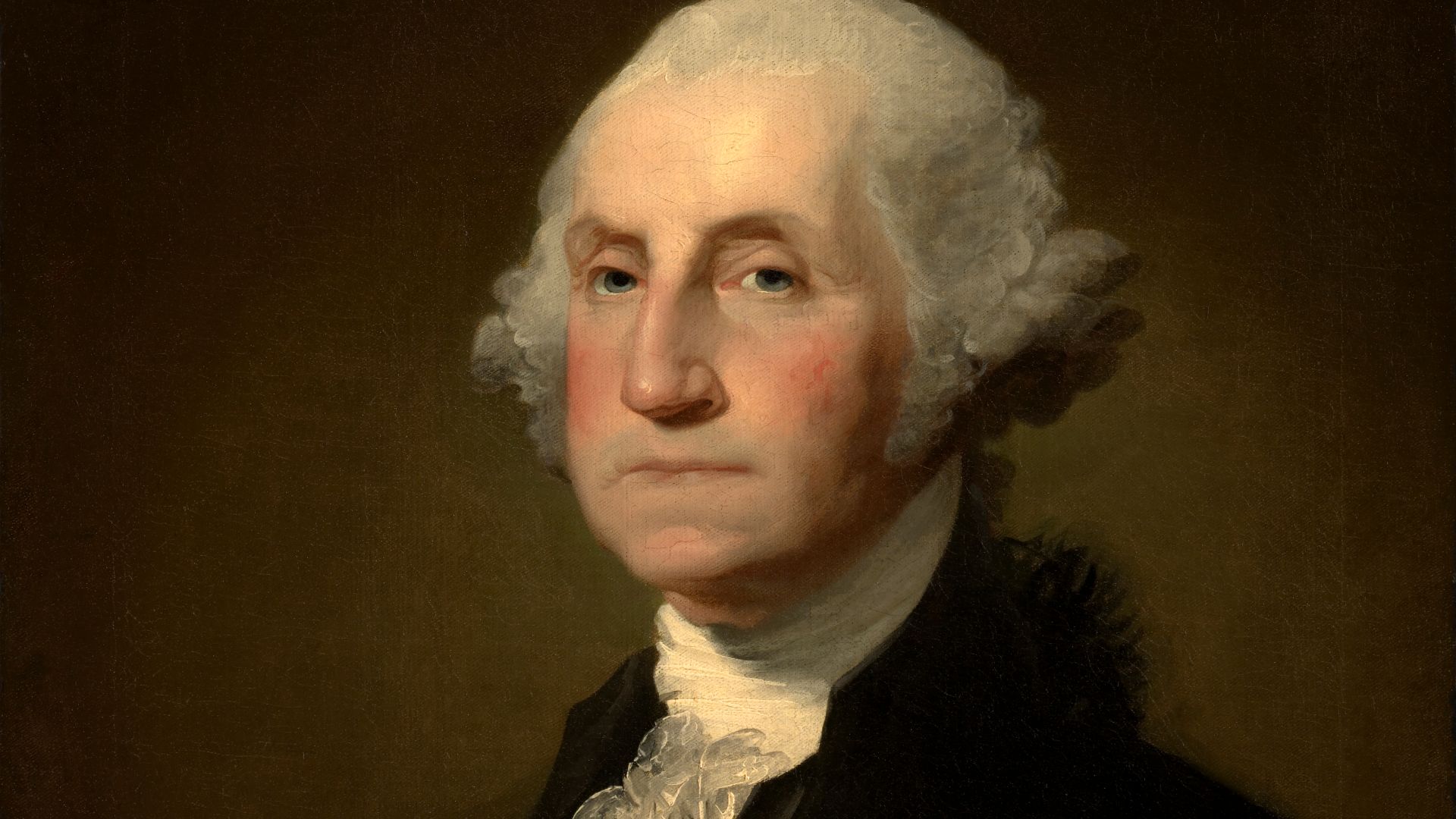

42. He Became Indispensable

Benjamin Franklin operated in Europe until 1785, when he came back and resumed his duties in the colonies. By this point, his accomplishments and the admiration people showed him were enough to make him the embodiment of fighting for American independence, surpassed only by George Washington in his commitment and zeal.

Fortunately, he still knew how to use his sway.

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

Gilbert Stuart, Wikimedia Commons

43. He Had A Major Change

In previous years, Franklin had begun speaking out against slavery and advocating for certain changes, but he still owned two slaves himself. That was until his return to America in 1785, when he made the complete switch and freed his slaves, subsequently joining and rising to the position of president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society.

Although this view angered many, he still held a seat in government.

NMGiovannucci, Wikimedia Commons

NMGiovannucci, Wikimedia Commons

44. He Was Given Leadership

Even after speaking out so radically—possibly even because he did so—the people of Pennsylvania still loved Benjamin Franklin. The same year he returned to America, he earned the elected position of President of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania, which was effectively the role of the state’s governor.

Sadly, this would be one of his last great achievements.

45. His Health Worsened

The gout Franklin had experienced in his middle-aged years was just the tip of the iceberg of his health problems and was a result of the obesity he suffered from for the rest of his life. In 1787, he signed the US Constitution, but was noticeably worse for wear in his increased age and scarcely went out in public after this to the day he lay on his deathbed.

Of course, he wasn’t about to shy away from one last adage.

William Harry Warren Bicknell (1860–1947), Wikimedia Commons

William Harry Warren Bicknell (1860–1947), Wikimedia Commons

46. He Remained Insightful

As Benjamin Franklin inched closer to the end in bed at home with his daughter by his side, he couldn’t resist imparting one last piece of wit on April 17, 1790. Noticing his labored breathing, his daughter suggested he turn on his side to make things easier. In response, Franklin stated, "A dying man can do nothing easy," before passing from a pleuritic attack.

If there was one thing to remember about him, it was his constant desire for growth.

47. He Changed His Stance

It’s difficult to discern a historical figure’s true character, especially when other Founding Fathers criticized slavery while still owning slaves. Still, to Benjamin Franklin’s credit, his viewpoint truly seemed to evolve. Aside from freeing his slaves and being president of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, he wrote numerous essays to convince Congress, calling slavery "an atrocious debasement of human nature".

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

48. He Testified

Franklin's ownership of slaves wasn't the only mark on his honorable record. As a Freemason Grand Master, Franklin had many responsibilities, some of which were unpleasant. In 1738, two Freemasons put a man named Daniel Rees through dangerous hazing staged as an initiation, after which he perished. Although Franklin wasn’t present, he appeared in court as a witness since he knew about it beforehand and failed to prevent it.

After defending himself against public backlash, he went back to encouraging thoughtful discussions. And in the realm of technology, his work changed the world.

Alonzo Chappel, Wikimedia Commons

Alonzo Chappel, Wikimedia Commons

49. His Work Had Lasting Effects

Although Benjamin Franklin is often credited as the man who discovered electricity, the concept existed before his kite experiment, and no one person in history can truly claim its discovery. Even so, he’s responsible for furthering the understanding of electricity far beyond where it was, and for eventually inventing the lightning rod.

Of course, one accomplishment was his most unique of all.

Alfred Jones, for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jones, for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Wikimedia Commons

50. He Signed Them All

While John Hancock became known for his signature, and Thomas Jefferson authored the Declaration of Independence, Benjamin Franklin may have them both beat. Being one of the leading Founding Fathers, he involved himself in many of America’s most fundamental moments. As such, he is the only person to have signed the Declaration of Independence, the Treaty of Alliance with France, the Treaty of Paris, and the US Constitution.

Howard Chandler Christy, Wikimedia Commons

Howard Chandler Christy, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

The Truth About America’s Greatest President

The Many Contradictions Of President Thomas Jefferson

Revolutionary Facts About The Founding Of The United States Of America