“Would that thy love, beloved, had less trust in me, that it might be more anxious!” ―Héloïse, The Letters of Abélard and Héloïse.

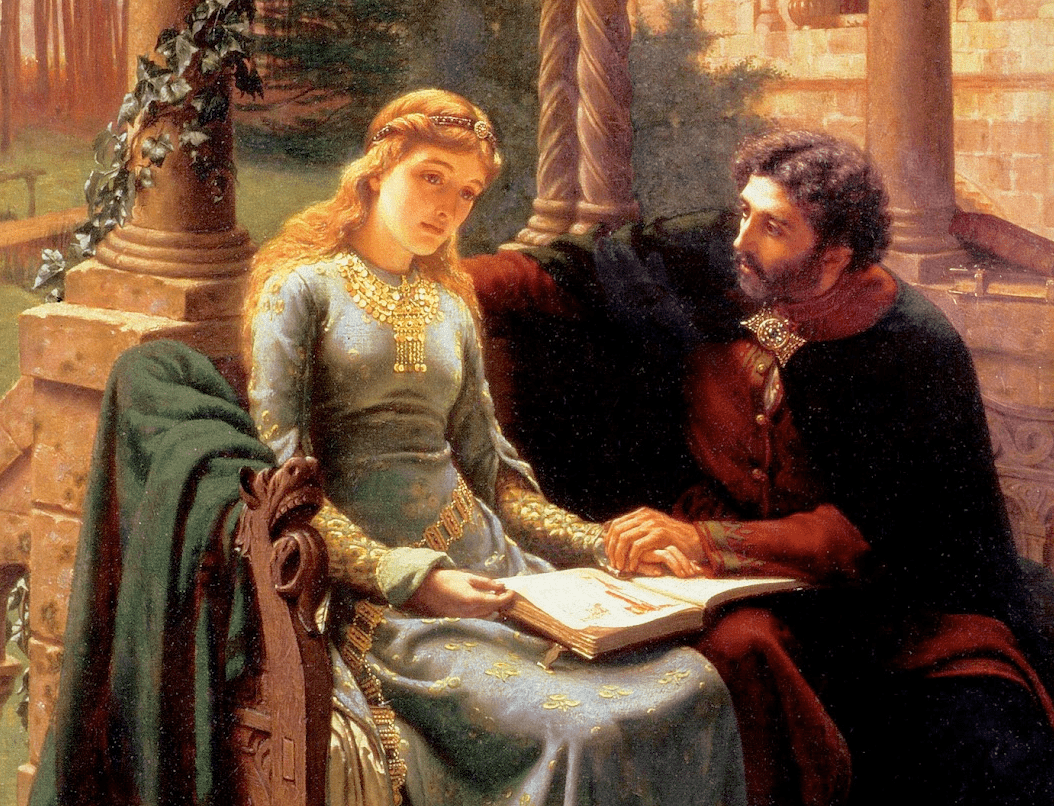

Before there was Romeo and Juliet, there was Héloïse and Abélard—the star-crossed medieval lovers whose affair crossed social boundaries of class, education, gender, and even the decorum of the Church itself. When their affair began, the pair were a tutor and his pupil; when it ended, they were a monk and nun, separated by scandal but still in each other’s lives thanks to the power of written word. The journey from the classroom to the Church was fraught with love letters, pregnancy, broken vows, and yes, even castration.

The tale of Héloïse and Abélard continues to scandalize romance lovers to this day. Was Abélard really the perfect gentleman? Was Héloïse really the fairy tale lady of courtly love fantasies? And what ever happened to their baby? Don’t tell Uncle Fulbert—or the Pope—about these 42 lesser-known facts about Héloïse and Abélard.

1. Looking For Something Causal

Abélard wasn’t looking for long-lasting romance: he was looking for a booty call. In a letter, the tutor admitted himself that he was already on the look-out for a potential mistress to help him kill time between study sessions. Although several ladies piqued his interests, only Héloïse snared his attention for long because, in his words, he wasn’t partial to “easy pleasure".

2. Make Me Fight For You

Abélard was attracted to Héloïse’s (apparent) “hard to get” routine. To quote his letters, “I was ambitious in my choice, and wished to find some obstacles, that I might surmount them with the great glory and pleasure". Hey, some guys like the hunt more than the catch.

3. All According To Plan

Abélard based his “plan” to seduce Héloïse on a glance. He saw a beautiful lady on the Parisian streets, who turned out to be Héloïse, and decided he should have her. Abélard found himself in her uncle’s household, where he was hired as a tutor, and the rest was premeditated romantic history.

4. Meet Me In The Pews

According to some biographers, Héloïse and Abélard got “busy” in a church refractory—but only after much convincing from Abélard.

5. Can’t Put A Ring On It

The lack of wedding ring between Héloïse and Abélard wasn’t the only cause for concern; Abélard was a scholar of the lower clergy, a class which Medieval European society deemed “unseemly” for marriage. At this time, men of Abélard’s station were expected to take vows of chastity like they were monks and priests, which made relations with women problematic to say the least.

6. Moving On Up

Héloïse was probably born to a lower social status than Abélard. This runs counter to the popular imagination of courtly love, where a lower-born suitor pines for an unattainable highborn lady. In truth, while Héloïse came from some money and connections, her birth paled in comparison to Abélard, who was born to the nobility but rejected his blue blood for a career in the books.

7. Beauty And Brains

By the time she met Abélard, Héloïse was already a reputed scholar and writer in her own right. In fact, her education had already rendered her France’s most famous woman at the time. Abélard later admitted this was part of her appeal…

8. The Healing Touch

Under Abélard, Héloïse’s already impressive education was extended to medicine. This physical knowledge was useful in her future career as an abbess, where she gained a reputation for her healing skills.

9. Old Enough

Héloïse was a student, but she was probably not a child. While her exact age at the time of her affair is lost to time, historians now generally agree she was in her early 20s. For centuries, she was assumed to be about 17 until it was pointed out there was no contemporary basis for this assumption. Her intellectual reputation, plus her grasp of Greek and Hebrew, strongly suggest she was at least 20.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. Where In The World…

Other “romantic” settings for the couple’s physical encounters including the convent kitchens and even the bed of Héloïse’s own Uncle Fulbert. Cozy.

11. Let’s Make A Deal

How did Abélard land a room in Fulbert’s house? He convinced the well-connected canon that he couldn’t afford to live in his current pad and offered a deal: tutor Fulbert’s niece Héloïse in exchange for room and board. Abélard was a very respected scholar at the time, so it sounded like a sweet deal for Fulbert—and Héloïse.

12. A Star Is Born

Héloïse and Abélard’s affair resulted in a son, whom they named Astrolabe. For the record, an “astrolabe” is also the name of an old-fashion navigational device that helps astronomers figure out the Earth’s position in relation to the stars. Nerd parents will be nerd parents.

13. Where’s The Baby?

The fate of Héloïse and Abélard’s lovechild is lost to history. His mother never mentioned him in her letters while his father mentioned him once in passing. We know the day of his death (October 29 or 30), but not the year.

14. I Know Something You Don’t Know

To smooth things over with her uncle, re: that illegitimate pregnancy, Abélard agreed to marry Héloïse. However, the marriage had to be kept secret, or else it would ruin the scholar Abélard’s career. Nevertheless, Fulbert began to spread rumors about the marriage as revenge against Abélard’s damage to the family reputation.

15. Cut It Out Or I Will

By the time of their son’s birth and their marriage, it was rumored Abélard was already beginning to lose interest in his once-pupil and lover Héloïse—perhaps because he’d sent her to a convent. Shortly after, Héloïse’s uncle Fulbert arranged for Abélard to be castrated in revenge for Héloïse’s convent trip, which her uncle believed was an attempt to dump her. This act humiliated Abélard, but also threw a towel over his wandering eye.

16. Breaking The Glass Ceiling

In 1129, Héloïse had risen to become the prioress of an abbey…but as it turns out, the abbey was about to be taken over by the Abbey of St Denis, which happened to be the abbey where her ex-lover Abélard was now a monk. To his credit, he arranged new digs for them: the Oratory of the Paraclete, where Héloïse continued to rise to the rank of abbess.

17. Not Writing Valentine’s Day Cards Anytime Soon

Héloïse was never hot on marriage. Even when she got pregnant, she initially said “no” to the dress and needed convincing. Her later writings about marriage show that she hardly warmed to the institution: “I preferred love to wedlock, freedom to a bond". She also rhetorically asked, “What man, bent on sacred or philosophical thoughts, could endure the crying of children…? And what woman will be able to bear the constant filth and squalor of babies?"

18. Take A Hint, Girl

Even after their religious enclosures, Héloïse maintained correspondence with Abélard. She wrote about her still-enduring love for him; Abélard, it was rumored, had reiterated that their relationship was a sin and that they should just commit themselves to God.

19. Together 4 Ever

In 1142, Abélard passed on, aged 63. Héloïse would outlive him by 20 years, later dying in 1163. The couple were ultimately buried side-by-side.

20. Seal The Tomb With A Kiss

Héloïse and Abélard’s remains have been moved multiple times, but it’s believed their final resting place has been at the Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris since 1817. Lovers—or just the lovelorn—will leave letters behind in their crypt, both in hopes of paying respect to the couple or to increase their chances of finding true love themselves.

21. Habeas Corpus?

In truth, where Héloïse is buried remains much-disputed. While it’s generally accepted Abélard is there at the Père Lachaise Cemetery, others think Héloïse was really buried elsewhere.

22. May-December

Peter Abélard was at least 15 years older than his beloved Héloïse.

23. Inheriting The Habit

Héloïse’s mother might also have been a scandalous nun. While the identity of her father remains a mystery, Héloïse’s mother was possibly a nun named Hersint, who resided at the St. Eloi convent—an institution that was eventually shut down based on charges of mass carnal misconduct. It was common for children of disobedient nuns to be raised in other convents, and it’s better known that Héloïse grew up in a Benedictine convent near Paris. Make of that what you will…

24. Extra Credit

In his memoirs, Abélard wrote of his “sessions” with Héloïse that they shared “more words of love than of our reading passed between us, and more kissing than teaching". Not exactly earning that rent there, Peter.

25. Light A Match To Our Love

Héloïse and Abélard most likely exchanged their love letters on wax tablets. Hinged like a book, the tablets would be inscribed with messages and closed to be passed on by a servant. The recipient would read the message, smooth the wax over, and then re-use the slab to write their reply. What a sticky way to be sweet.

26. First Draft

Although their love was written in erasable wax, some remnants of their letters survive in Héloïse’s paper scraps. Seeing as they exchanged love notes in wax, it made sense for Héloïse to “practice” in pen before she committed to the candle.

27. Mistress Of Disguise

In her state of unwed pregnancy, Héloïse was snuck away from the city while disguised in a nun’s habit. This was before she took vows.

Wikimedia Commons Alex Proimos

Wikimedia Commons Alex Proimos

28. He Could Do The Time, So He Did The Crime

For his part in the castration of Abélard, Uncle Fulbert had his belongings seized and position revoked by the Bishop of Paris. At least for a while: after two years, in 1119, Fulbert’s signature begins to appear again on important Notre Dame documents. I guess he paid his debt to society—if not to Abélard.

29. Friend Request

There was a 12-year “gap” between their separation and their correspondence. Once Abélard published in harrowing memoir, Historia Calamitatum (or Story of My Misfortunes), Héloïse reconnected with her love. However, they would never live with each other again.

30. Going Into The Family Business

In some versions of the story, Héloïse and Abélard’s son, Astrolabe, also enters the faith. It’s often believed he became the abbot of Swiss monastery.

31. The Artist Formally Known As Abélard

“Peter Abélard” was really born “Pierre le Pallet” in about 1079. He spent much of his early academic career wandering around Paris. After a sojourn to the Notre-Dame Cathedral, he began to develop his professional surname, sometimes written as “Abailard” or the less catchy “Abaelardus".

32. Teaching The Teacher

Abélard developed a reputation for being arrogant with his teachers. One of them, William of Champeaux, apparently became hostile to the young Abélard because the pupil beat him in an argument—of course, that’s in Abélard’s retelling of it. William would try to prevent Abélard from teaching in Paris, where they became professional rivals over theories of the universe.

33. Persona Non-Grata

Abélard’s post-Héloïse career was hardly peaceful. His writings got him in trouble with the Church, who condemned him as a heretic. While he escaped a burning, his blasphemous writings did not.

34. See It To Believe It

Uncle Fulbert doesn’t come off great in this story (see: the castration), but it appears he did love his niece, providing her with a rich education and refusing to believed she “sinned” with her tutor…even as rumors of her affair swirled. He might have only believed the rumors after walking into Héloïse and Abélard in the “act".

35. Look At Me!

Was Abélard’s memoir a fame-grab? On one hand, it’s largely why the love story of Héloïse and Abélard survives. On the other hand, some believe he only published the scandalous book for attention and to keep his name in the public.

36. A Matter Of Church And Learning

As a monk, Abélard thought about abandoning Christianity altogether. Why? The other monks were highly disapproving of his teaching the secular arts.

37. The Pope Says No

On July 16, 1141, Abélard was officially excommunicated from the Catholic Church for his writings. He managed to escape the same fiery fate as his books thanks to Peter the Venerable, abbot of Cluny. Peter convinced the now-old Abélard to give it up and just keep the monastery.

The Pope agreed to lift Abélard’s excommunication if the wayward monk stayed under the trusted Peter’s surveillance for the rest of his life—which would prove to be only a year long, as he died on April 21, 1142, very much unburned.

38. Beauty Is Only Skin-Deep

Abélard’s presumed cause of death gets rather unromantic: he likely perished from a combination of a fever and a skin disorder—likely scurvy.

39. How Much Say-So?

In recent years, scholars have been skeptical as to how “willing” Héloïse was in their relationship. To call attention to one of Abélard’s letters to Héloïse: “When you objected to [intercourse] yourself and resisted with all your might, and tried to dissuade me from it, I frequently forced your consent (for after all you were the weaker) by threats and blows".

40. The Authorship Question

Did Héloïse really write her now famous letters to Abélard? Some people think she didn’t. It’s not a mainstream opinion, but it’s held strongly by thinkers like John Benton. Skeptics of the skeptics will argue this viewpoint is largely fueled by bias. Either way, it makes for good reading.