The Map That Changed Everything

Every famous map begins with careful planning, except the one that didn’t. In 1525, a Bible introduced a Holy Land map printed completely backwards. Strangely, readers trusted it anyway. That small slip created a quiet distortion that affected people for centuries.

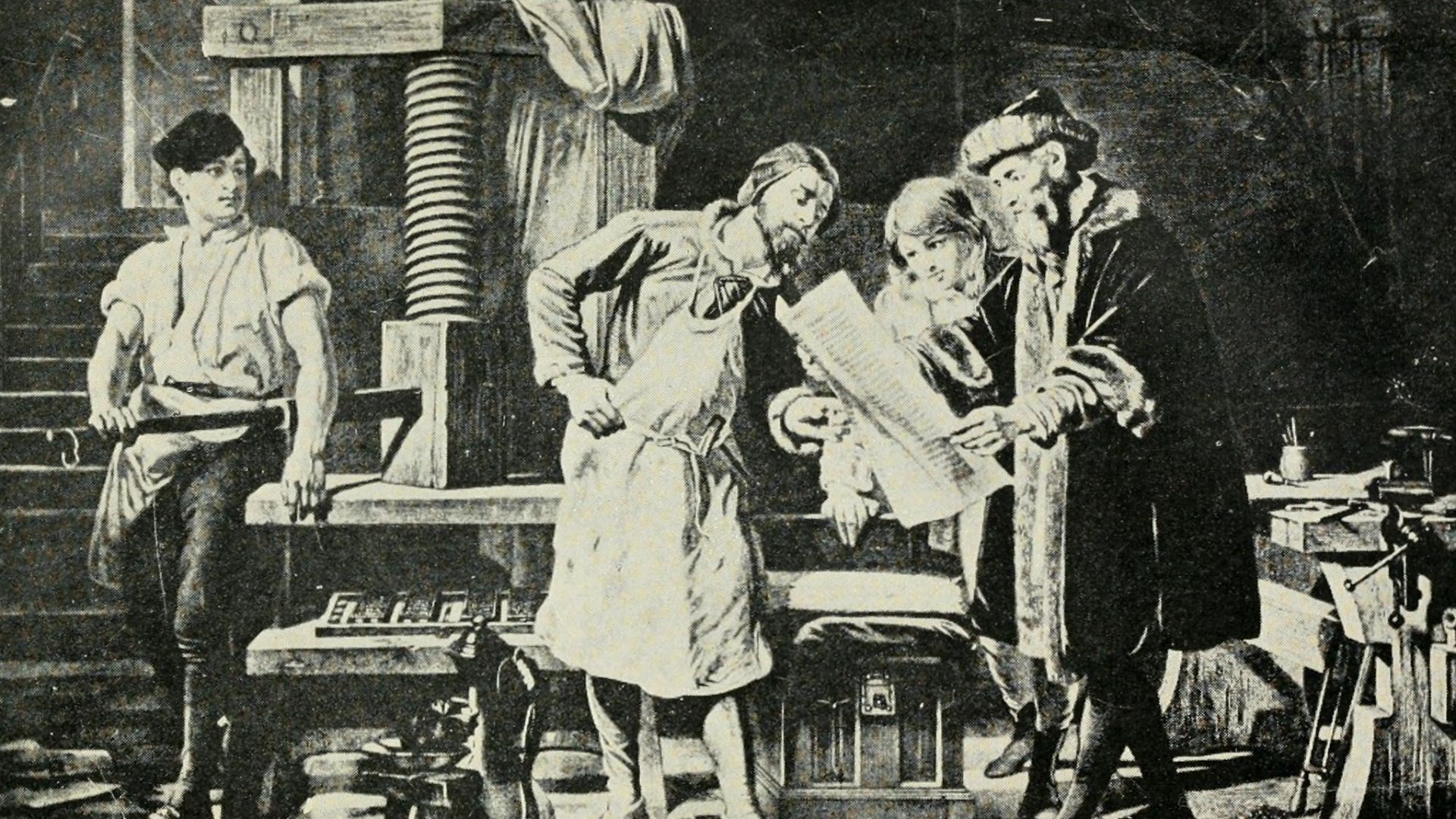

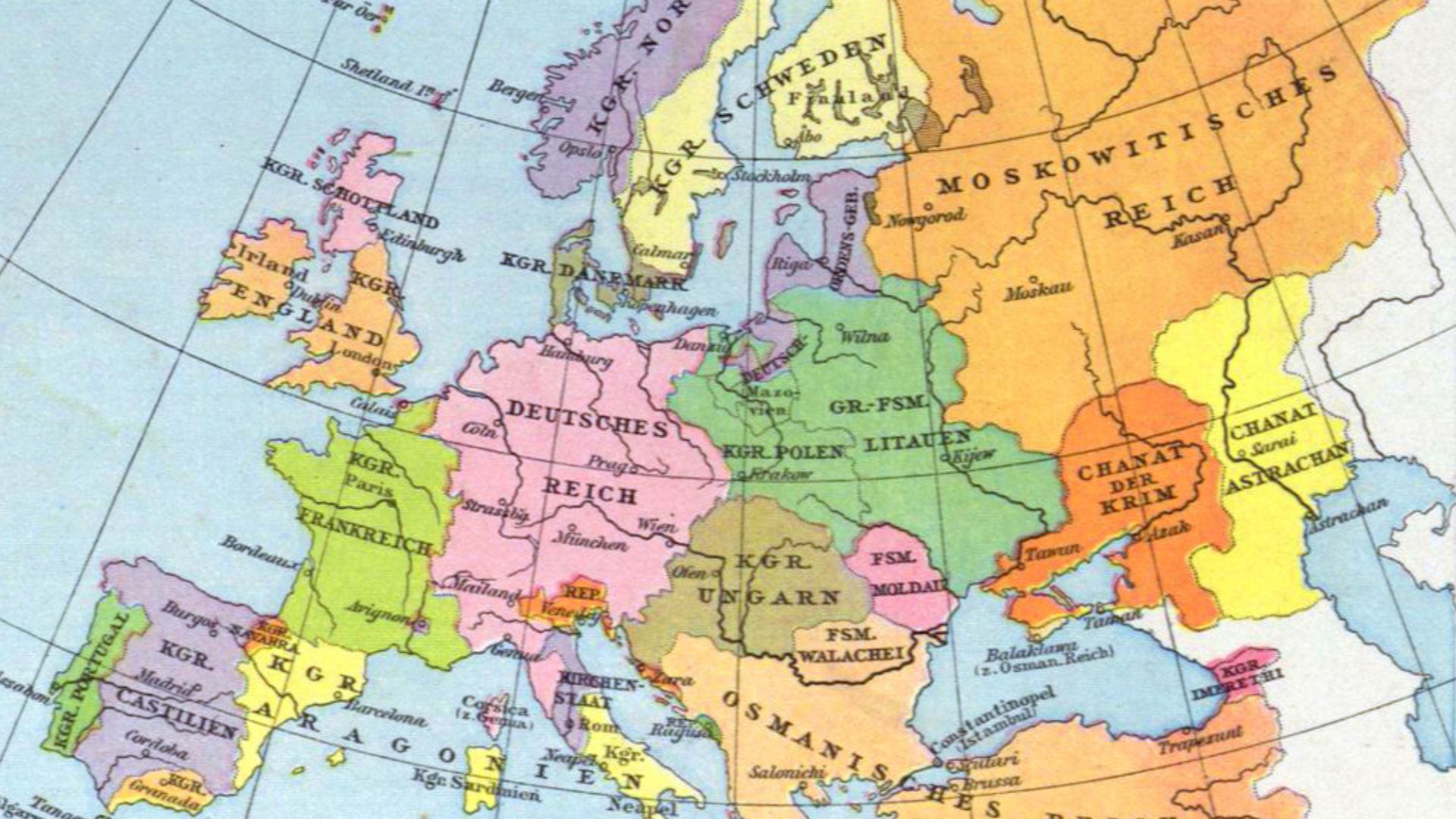

Europe In 1525 Was Rethinking Almost Everything

Europe in 1525 felt unsettled. Old beliefs were being challenged, new voices were rising, and printing presses spread ideas faster than anyone expected. People were suddenly reading the Bible themselves, which changed how they thought about faith and the world around them.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Why Bibles Suddenly Needed Maps

As more people read scripture on their own, they wanted to picture where these stories happened. A map helped turn ancient names into real places. It made distant events feel closer, like you could almost trace the journeys with your finger across the page.

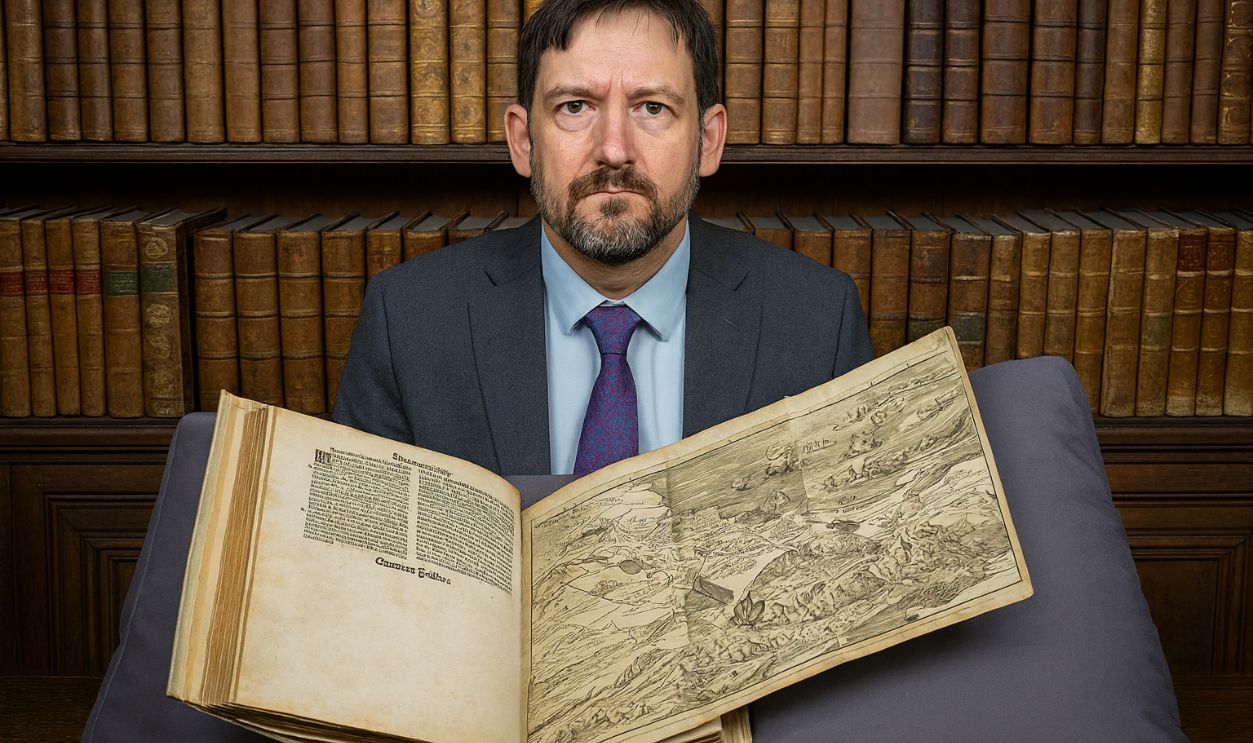

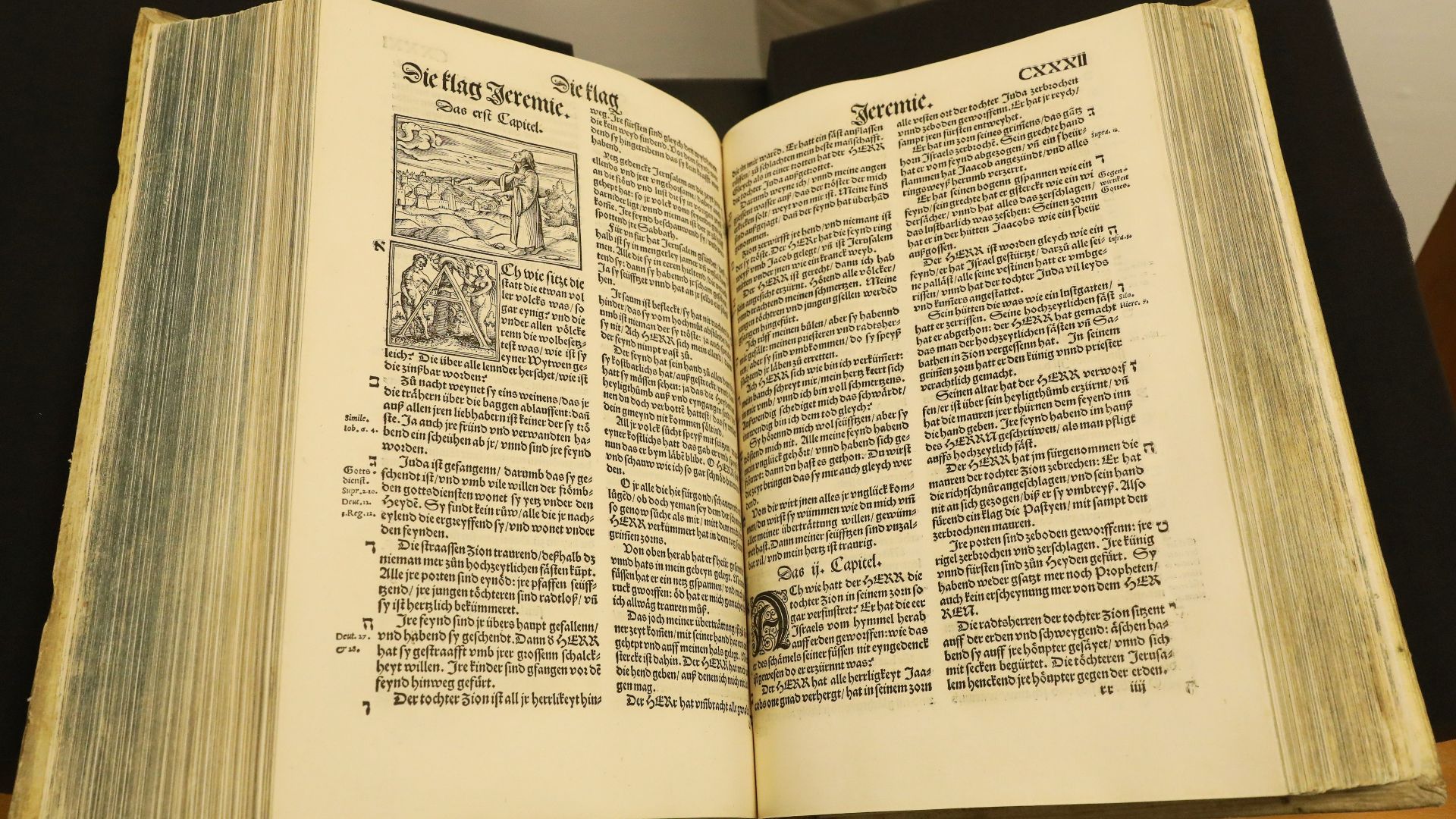

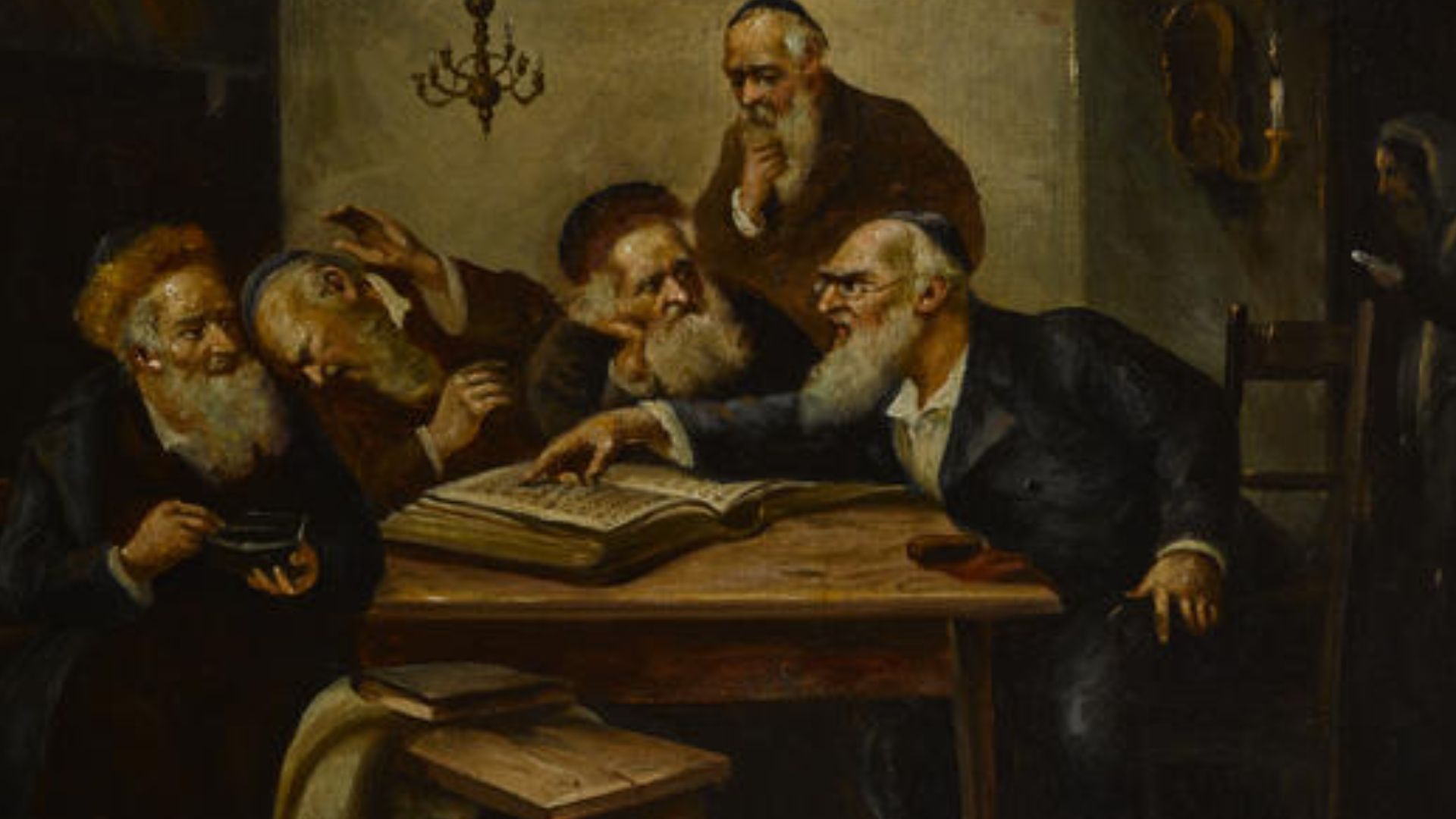

The Zurich Bible And Its Makers

The backwards map appeared in a German Bible printed in Zurich by Christoph Froschauer, one of the busiest printers of the Reformation. Zurich, influenced by the preacher Huldrych Zwingli, encouraged books that ordinary readers could understand without needing Latin or special training.

Martin Rulsch, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Rulsch, Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons

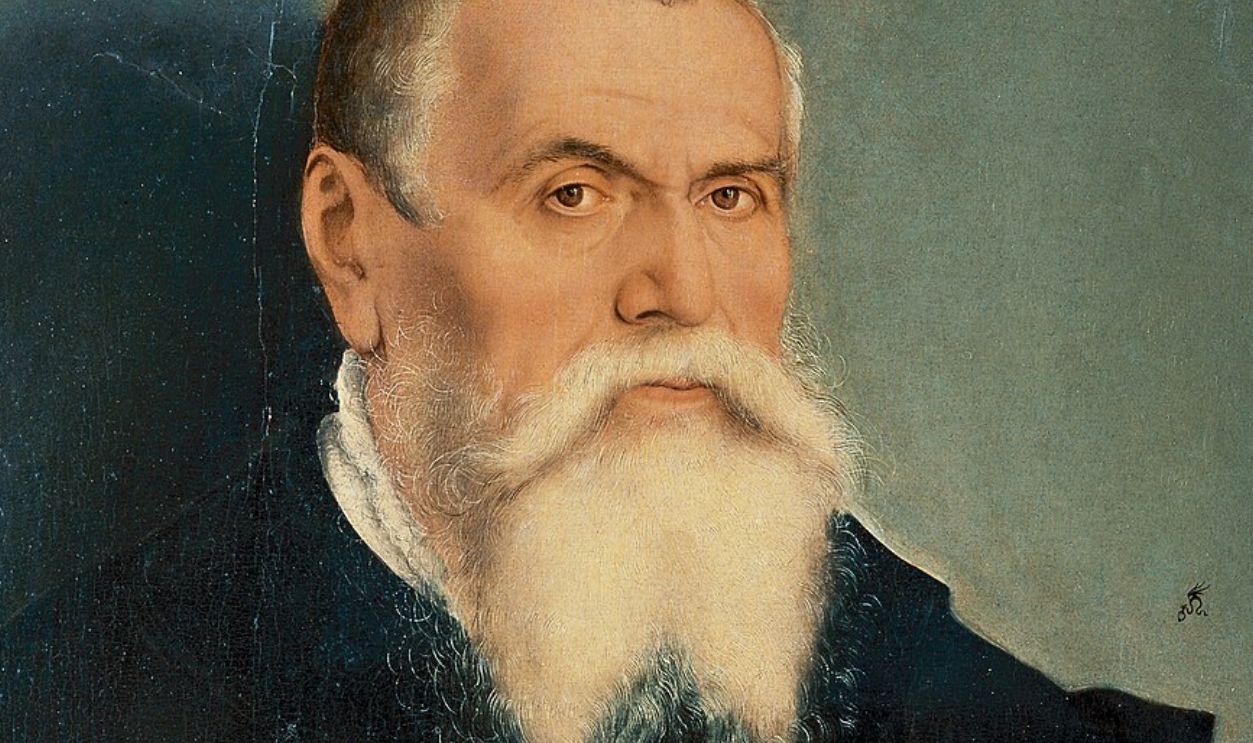

The Artist Behind The Image

The map is connected to Lucas Cranach the Elder or his workshop, and he was a respected German artist known for clear, bold woodcut illustrations. He worked with leading reformers and created images that helped readers make sense of stories that once lived only in sermons.

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Wikimedia Commons

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Wikimedia Commons

How People Saw Maps Before Cranach

Before printed atlases, most Europeans knew maps as symbolic drawings that placed Jerusalem at the center of the world. These images weren’t meant for navigation. They blended faith and geography, offering a spiritual picture of the world rather than a realistic one.

Gustav Droysen, Wikimedia Commons

Gustav Droysen, Wikimedia Commons

The Holy Land As A Place People Wanted To Picture

For centuries, the Holy Land existed in most minds as a mixture of scripture and imagination. Pilgrims described it, scholars debated it, and artists tried to sketch it. A clear map promised something new: a way to picture these stories as events anchored in real space.

Bernard Trebacz (1869-1941), Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Trebacz (1869-1941), Wikimedia Commons

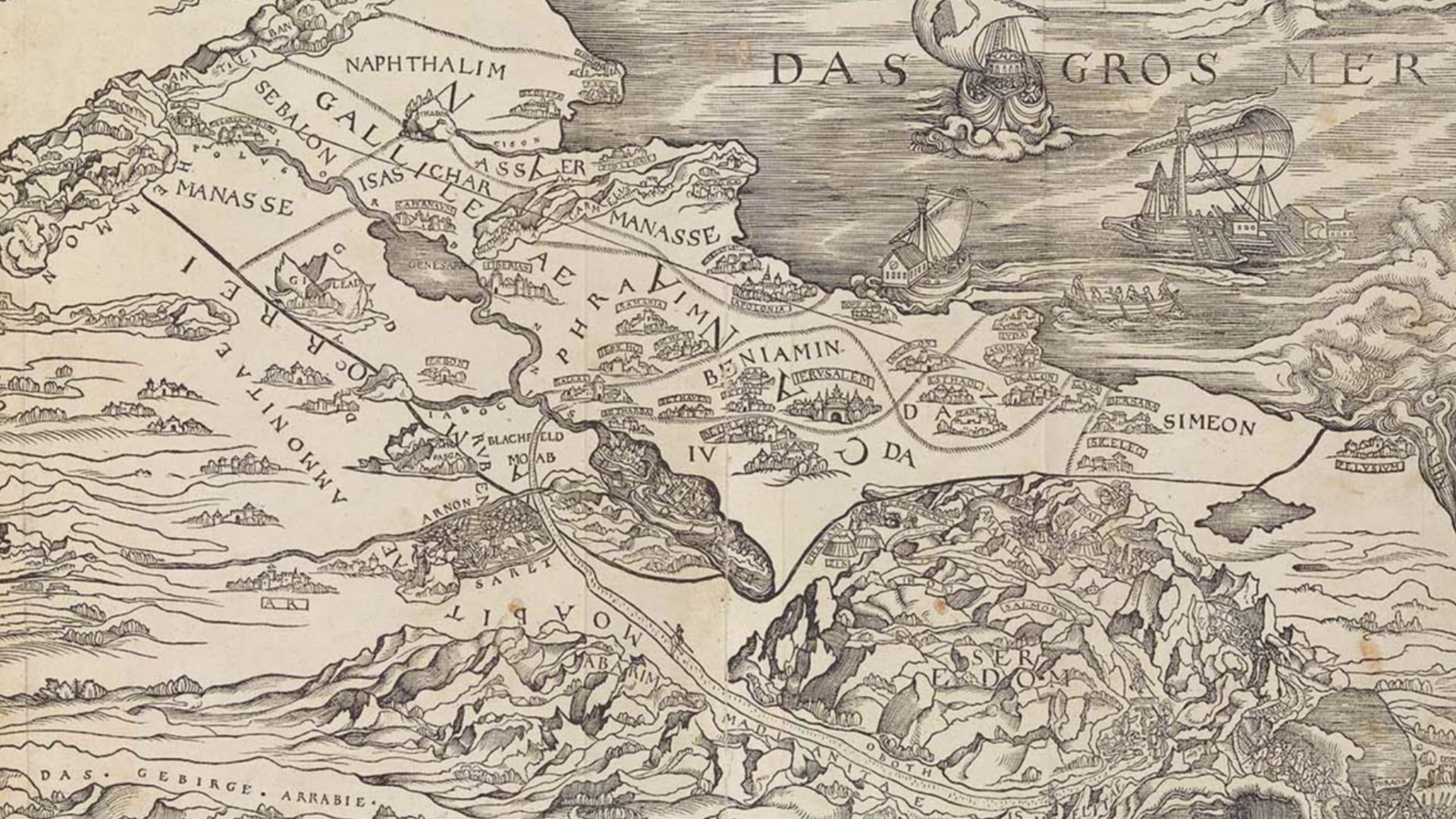

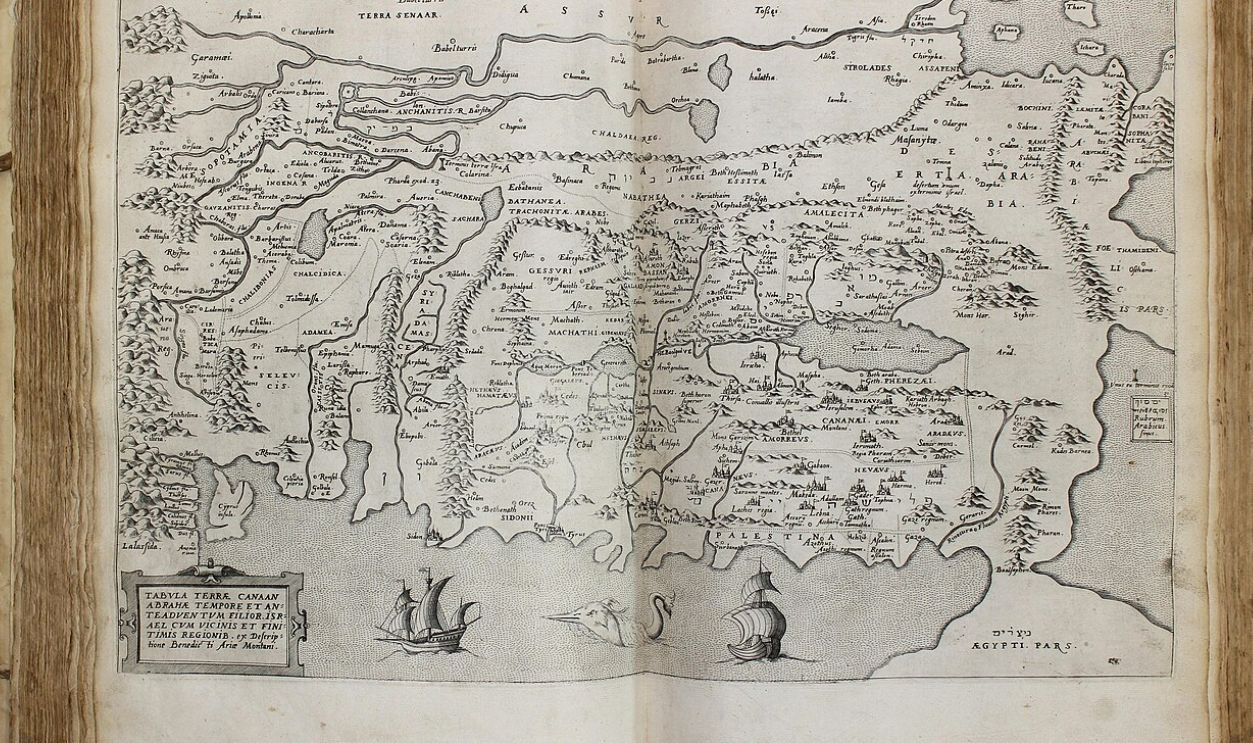

How The Map Was Designed

The 1525 map relied on earlier sketches and written descriptions of ancient Palestine. It showed the places mentioned in the Old Testament. Made as a woodcut, it carried Cranach’s bold lines, turning complex geography into a simple image readers could follow.

Lucas Cranach, Wikimedia Commons

Lucas Cranach, Wikimedia Commons

Why The Printing Error Happened

Woodcuts print as mirror images unless reversed ahead of time. If the design isn’t flipped on the block, the final print appears backwards. That’s what happened here. The carving was correct, but the print wasn’t, and no one was aware of that.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

The Mediterranean On The Wrong Side

The most noticeable error was the coastline. On the map, the Mediterranean Sea appeared east instead of west. Anyone familiar with real geography would spot it instantly, yet most readers didn’t. They trusted the printed page more than their limited geographic knowledge.

Aa, Pieter van der, 1659-1733, Wikimedia Commons

Aa, Pieter van der, 1659-1733, Wikimedia Commons

Why Almost No One Noticed The Mistake

Geography wasn’t common knowledge in 1525. Many readers had never seen accurate regional maps, and travel was limited. If a Bible printed something, people assumed it was correct. The reversed layout simply blended into their understanding of a distant place they’d never visited.

Frank William Warwick Topham, Wikimedia Commons

Frank William Warwick Topham, Wikimedia Commons

How Readers First Responded

No letters of complaint survive, and no early editions corrected the map, which suggests people accepted it. They used it as a visual aid, focusing on biblical names rather than directions. The map’s authority came from the Bible itself, not from geographic accuracy.

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Wikimedia Commons

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Wikimedia Commons

Why Maps Changed How People Read Scripture

Most medieval Bibles had no maps, so adding one felt new and exciting. It let readers picture the Holy Land as real ground rather than a distant setting. Even reversed, the map gave journeys and events a sense of place, making scripture feel anchored in history.

Elisabeth Baumann, Wikimedia Commons

Elisabeth Baumann, Wikimedia Commons

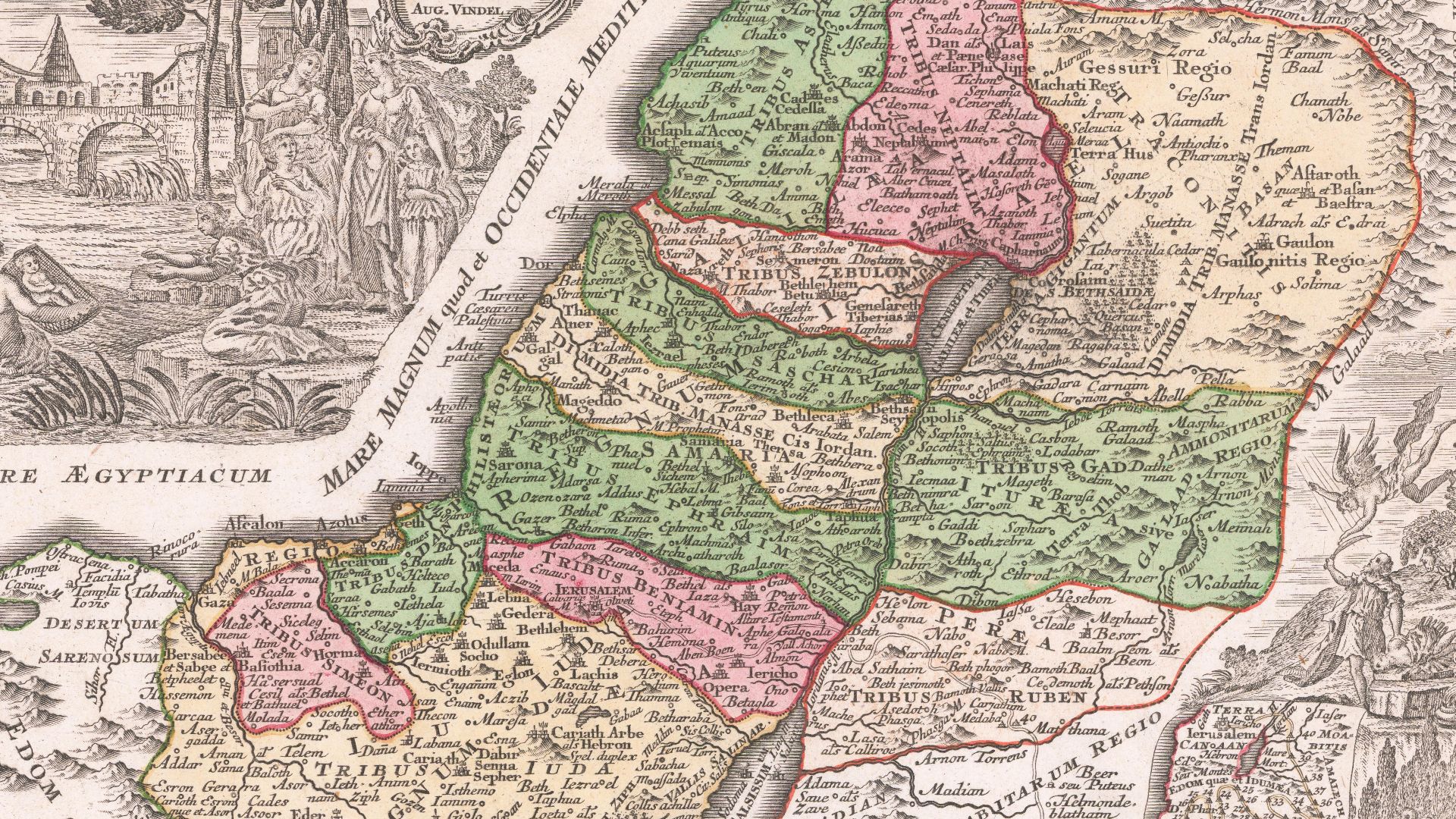

Tribal Boundaries That Looked Like Territorial Lines

The map showed the twelve tribes of Israel as clear, divided regions. These divisions came from scripture, not political maps, yet readers saw them as borders. Even reversed, the layout encouraged people to imagine the Holy Land as a patchwork of defined territories.

Giuseppe Rosaccio, Wikimedia Commons

Giuseppe Rosaccio, Wikimedia Commons

How The Map Quietly Fed Emerging Political Ideas

The neatly separated tribal areas offered more than a Bible study aid. They echoed ideas forming in Europe about organized territories and defined groups. Readers who saw ancient communities arranged so clearly could imagine political identity in similar ways, even though real borders were far less stable.

Arnoldus Montanus, Wikimedia Commons

Arnoldus Montanus, Wikimedia Commons

Bible Maps Spreading Across Europe

The idea caught on. By the seventeenth century, many European Bibles included maps. They weren’t identical, but they built on the same concept: turning scripture into geography. The reversed 1525 version helped set that template by showing there was a demand for visual guidance.

juxtapose^esopatxuj, Wikimedia Commons

juxtapose^esopatxuj, Wikimedia Commons

Influence On Later Cartography

As maps became more common, cartographers shifted toward clearer borders and labeled regions. The early Bible maps didn’t cause this trend alone, but they contributed to a growing habit of imagining land as something divided, named, and structured—ideas that became central to later mapping.

Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, Wikimedia Commons

Eran Laor Cartographic Collection, Wikimedia Commons

How Politics Looked Before Borders Became Normal

In early sixteenth-century Europe, power wasn’t tied neatly to lines on a map. Authority shifted through marriages and alliances. A map inside a Bible felt unusual because it pictured land as something that could be arranged on a page, not negotiated through families.

Peter Baumgartner, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Baumgartner, Wikimedia Commons

Why The Map Appealed To Leaders As Much As Readers

Rulers and church figures lived in an age of constant disputes over land and influence. A biblical map that sorted ancient groups into clear spaces offered a comforting order. It let political thinkers imagine older worlds as tidy models, even if reality was far less organized.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

How Maps Began Changing Political Imagination

As printed maps circulated, people slowly adopted a new habit: thinking of regions as shapes with boundaries rather than loose zones of influence. The reversed Bible map wasn’t accurate, yet it trained viewers to see territory as something that could be measured, drawn, and discussed.

Willem van Mieris, Wikimedia Commons

Willem van Mieris, Wikimedia Commons

Where Surviving Copies Ended Up

Only a few original 1525 editions remain today. Some sit in major libraries and archives, where their fragile pages reveal early printing methods. These copies show how widely the map circulated and how long it stayed in use without being corrected.

Why Scholars Treat Old Maps Carefully

Historians warn against reading these early maps as exact records. Many blended faith, tradition, and limited knowledge. The reversed map reminds us that accuracy wasn’t the goal. It was created to help readers through scripture, not to document the world as it truly looked.

School of Rembrandt, Wikimedia Commons

School of Rembrandt, Wikimedia Commons

How Mistakes Shape Culture More Than We Expect

History isn’t only shaped by grand decisions. Small errors leave marks too. The reversed map shows how a simple printing slip can ripple outward when people accept it. A mistake became part of everyday reading, guiding imagination long after the error was forgotten.

Matthäus Seutter, Wikimedia Commons

Matthäus Seutter, Wikimedia Commons

The Lasting Influence Of A Backwards Map

Even though later maps corrected the geography, the 1525 version left a quiet imprint. It helped popularize the idea that scripture could be pictured on a page, and it encouraged readers to see the Holy Land as a structured land rather than a distant idea.

Popular Graphic Arts, Wikimedia Commons

Popular Graphic Arts, Wikimedia Commons

What This Story Reveals About Knowledge And Belief

The reversed map shows how people trust what feels authoritative, even when it’s flawed. It reminds us that beliefs often form around the tools we use to understand the world. A simple picture can lead the imagination just as strongly as words on the page.