Two Unstoppable Leaders

It was a battle of tyrannical egos: In 1942, German Führer Adolf Hitler ordered his forces to conquer a city named after Soviet President Joseph Stalin. 200 days and 2 million fatalities later, Stalingrad lay in ruin, with German momentum crushed. Here’s how it happened.

Stalin’s Early Victory

Stalin’s connection to this important city on the Volga River was more than just in name. After the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, Joseph Stalin successfully commanded the Red Army’s push to take this crucial port from the White Army, which was sent packing to Crimea.

Museum of Political History of Russia, Wikimedia Commons

Museum of Political History of Russia, Wikimedia Commons

In Praise Of Himself

The year after Soviet icon Vladimir Lenin passed away in 1924, Stalin renamed the city of Tsaritsyn to Stalingrad. The old name had nothing to do with the Tsars, the feudal leaders of Russia kicked out of power in 1917. Instead, it was based on a Turkic name that meant “yellow river”.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Stalin’s #1 Enemy

Using terror and intimidation, Stalin purged his opposition to become undisputed leader of the USSR. He was keen to rebuild the Russian Empire on the ashes of the Bolshevik Revolution but faced another ruthless leader keen to expand: the undisputed leader of Germany.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library Public Domain Photographs, Wikimedia Commons

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library Public Domain Photographs, Wikimedia Commons

Germany’s Dangerous Path

The Führer had risen to power in 1933 as Germany struggled with the aftermath of WWI. He broke agreements with the victorious allies, restarted the country’s economy, and made the first steps in creating a greater Germany by annexing Austria and splitting up Czechoslovakia.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1990-048-29A, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1990-048-29A, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

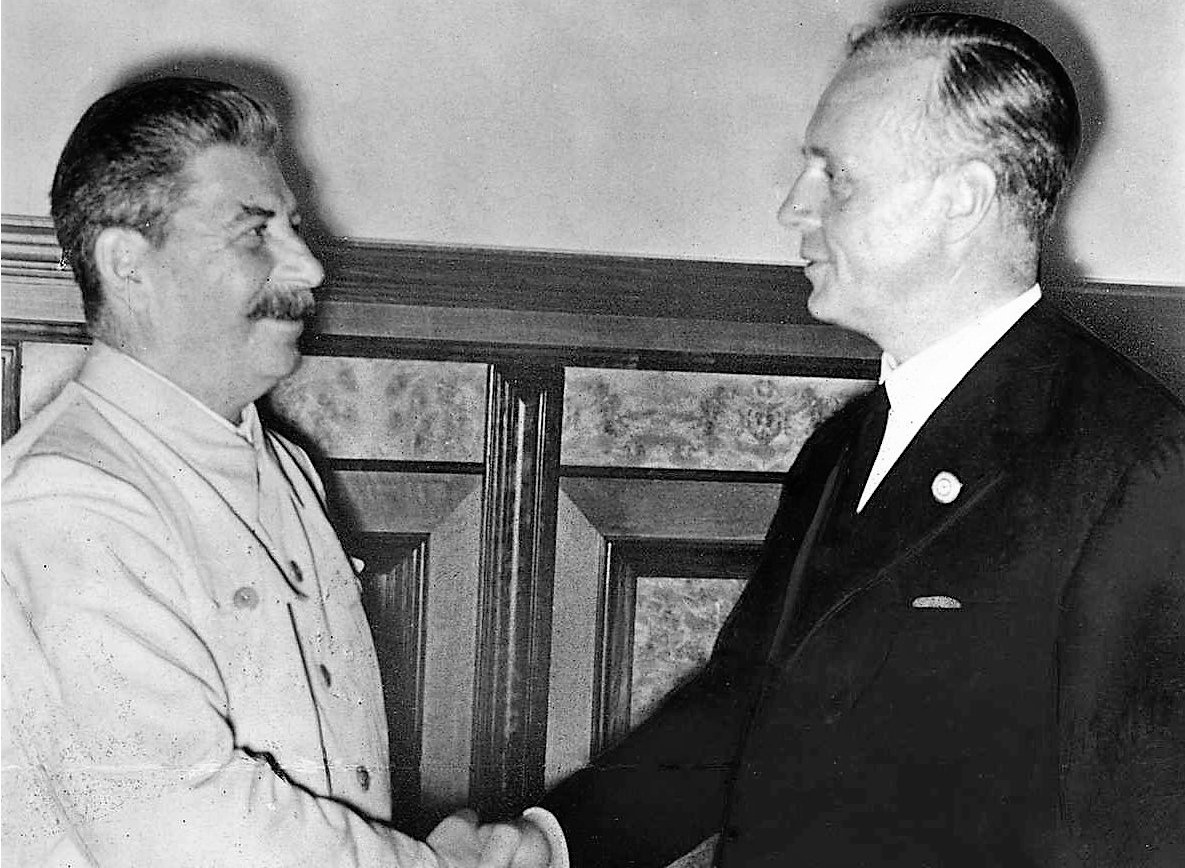

Sworn Enemies Shake Hands

Berlin next set its sights on Poland, precariously squeezed between Germany and the Soviet Union. But an invasion risked an angry response from Stalin. In a move that shocked the world, Germany and the Soviet Union signed a nonaggression pact in Moscow on August 23, 1939.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27337, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-H27337, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Meeting In The Middle

As Stalin looked on, the two countries’ foreign ministers signed the deal, which included secret provisions to carve up Poland and other countries in Eastern Europe. On September 1, Germany invaded Poland, and on September 17, the Soviets invaded Poland from the east.

DieWehrmacht, Wikimedia Commons

DieWehrmacht, Wikimedia Commons

The Clock Ticks

So how did these surprising allies end up fighting each other in Stalingrad three years later? The German leader had been convinced his country would have to fight the Soviet Union sooner or later, and by the end of 1940, ordered his commanders to prepare invasion plans.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-013-0068-18A, Höllenthal, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-013-0068-18A, Höllenthal, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Stalin Gets Pushy

Soviet moves, including invading Finland and annexing parts of Romania, were starting to alarm Germany. Stalin was warned his supposed ally might respond, but the strongman shrugged it off. Then, on June 22, 1941, the Führer launched his devastating Operation Barbarossa.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

All Seems Lost

The Soviet Union quickly lost all territory gained through the now-defunct non-aggression pact, and within six months, its forces suffered 4 million casualties. Meanwhile, German warehouses stored vital raw materials supplied by the Soviets under the ripped-up agreement.

Meyer Fritz, National Digital Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Meyer Fritz, National Digital Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Germans Approach Moscow

The end seemed near when German forces made it to within 250 miles (400 km) of the Soviet capital, but the German leader vetoed his generals and diverted units to Leningrad and Kyiv. The Red Army had time to regroup, giving it a crucial edge in the Battle of Moscow to come.

Schneider, National Digital Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Schneider, National Digital Archives, Wikimedia Commons

The Führer Targets Stalin’s City

Meanwhile, Germany’s Axis partner, Japan, hit Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, drawing America’s firepower to both European and Pacific fronts. An erratic Führer insisted on pressing eastward, leading to the disaster of Stalingrad and turning the tide against Berlin.

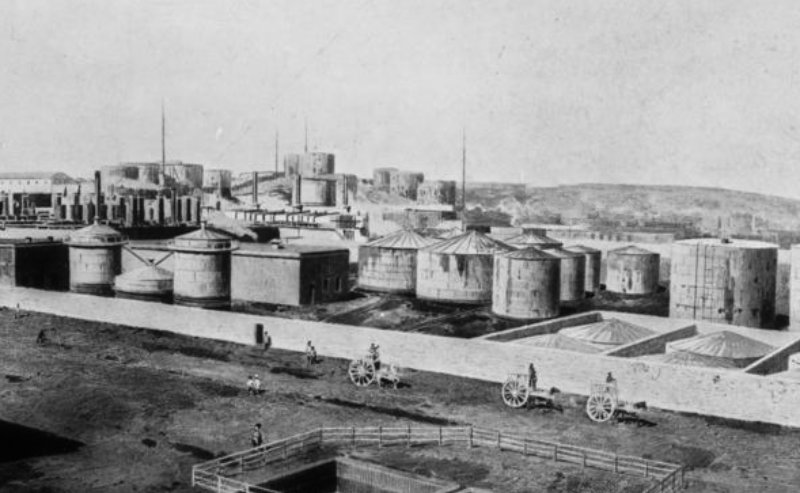

The Need For Oil

The German leader could have ordered another invasion of Moscow, which Stalin expected in 1942. But Germany was running out of oil and other natural resources. Controlling Stalingrad would mean controlling the Volga River and the route to the oil fields of the Caucasus.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R00738, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R00738, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Menace From The Skies

Stalin was so sure of an imminent move on Moscow that when Germany’s 6th Army reached Stalingrad on August 23, 1942, the Red Army was understaffed. With the German air force pounding the city and ground forces moving in, this industrial city was soon reduced to rubble.

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Victory Is So Close

German forces quickly captured 90% of Stalingrad, but they struggled to repeat their lightning drive over the steppes of Russia. The Wehrmacht was unfamiliar with the challenges of urban fighting as armed Soviets hid among the debris and destruction of the city.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B22478, Rothkopf, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B22478, Rothkopf, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Home Advantage

German ranks faced other risks. The Soviets knew their way through local sewers and tunnels and could resupply their forces. And while the Germans got bogged down fighting combatants, seemingly around each corner, the Red Army’s artillery rained down on the invaders.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Night Terrors

Soviet strategy included launching frequent night forays that would keep the jittery Germans awake to sap their morale. The Red Army would also interrogate fresh captives to determine upcoming battles and then strike at dawn before the Luftwaffe could fly over with air support.

RIA Novosti archive, image #2564, Samaryi Guraryi, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

RIA Novosti archive, image #2564, Samaryi Guraryi, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Fear Of Friendly Fire

By getting close to Axis forces, the Soviets could neutralize artillery support as the risk of friendly fire went up. The Soviets also used ambushes to separate Axis tanks and infantry, making them more vulnerable. Barbwire and minefields further menaced German positions.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L20582, Schmidt, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-L20582, Schmidt, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Both Sides Must Win

Both German and Soviet tyrants were unmoved by the human toll of this battle. The Red Army ruthlessly put down any idea of retreat, as did the German leader, even as the Soviets encircled his 6th Army. Increasingly desperate, he threw more units at the battle, pausing other battles.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

A Powerful Menace

German efforts suffered from a long supply chain, erratic coordination, and the Führer’s strategic blunders. And even as the German leader rejected retreat, Soviet forces planned a counteroffensive bolstered by reinforcements and a truly menacing weapon: the Russian winter.

Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive (SA-Kuva), Wikimedia Commons

Finnish Wartime Photograph Archive (SA-Kuva), Wikimedia Commons

Pincer Movements

In November 1942, Operation Uranus moved to encircle German forces in Stalingrad, first on the northwest and southeast. The two pincers would meet in the west at Kalach, while 300,000 Germans, cold and freezing, ran out of supplies. But the Führer still told them to stay put.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101III-Bueschel-090-39, Büschel, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101III-Bueschel-090-39, Büschel, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Cold Hell

Temperatures fell to –40° (the same in Celsius and Fahrenheit), with frostbite an ever-present danger. When gangrene set in, amputation was often the only remedy. The miserable conditions included hordes of mice that would feast on tank wiring, hobbling German defenses even more.

Commanders Buckle

Each side’s commander betrayed the strain. On the German side, Lieutenant General Friedrich Paulus developed a constant tic that spread from his left eye to much of his face. On the Soviet side, Lieutenant General Vasily Chuikov’s severe eczema kept his hands constantly bandaged.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-021-2081-31A, Mittelstaedt, Heinz, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-021-2081-31A, Mittelstaedt, Heinz, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Psychology Of Battle

But even though Soviet forces also faced the cold harsh conditions, they were better supplied and had the motivation to defend their own territory. Soviet loudspeakers also helped spread a deep sense of fear, announcing that one German invader was dying every seven seconds.

Yevgeny Khaldei, Wikimedia Commons

Yevgeny Khaldei, Wikimedia Commons

A Shortage Of Hope

The German leader had overestimated the power of his Wehrmacht after its stunning gains at the start of Operation Barbarossa. But his forces were useless if starved of food and other essentials. The Luftwaffe even tried airdropping supplies, but it just wasn’t enough.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B24543, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-B24543, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

No Mercy

German forces, starved and frozen, managed to defend their positions into January 1943, but the Soviets launched another offensive. Paulus pleaded for retreat, but the Führer responded by promoting Paulus to Field Marshal, adding that no Field Marshal had ever surrendered.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1971-070-73, Jesse, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 146-1971-070-73, Jesse, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Inevitable Surrender

But the situation had become utterly hopeless as even retreat now seemed impossible. On the last day of the month, Field Marshal Paulus surrendered what was left of his once-proud 6th Army, considered the cream of the crop. Germany had suffered a truly crushing defeat.

Imperial War Museums, Wikimedia Commons

Imperial War Museums, Wikimedia Commons

Stragglers Fight On

Some Germans carried on a guerrilla fight for another month or two, perhaps driven by patriotic fervor, perhaps by a fear of a horrible fate if the Russians got a hold of them. And such a fear was well founded. Most of the 90,000 captured German fighters suffered miserable fates.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

A Symphony Of Doom

Back in Germany, the somber tones of Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony interrupted the airwaves, followed by news of Germany’s dramatic defeat. On January 31, 1943, the German propaganda machine, for the first time, admitted a setback in the Führer’s drive to dominate the continent.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 116-168-618, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 116-168-618, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Red Army Reborn

The Soviet victory at Stalingrad had a huge impact. The Red Army, decimated by years of Stalin’s purges, had finally shown it had the strategic chops to fight Germany, signaling to the German leader and the world it was a strong and cunning force to be reckoned with.

RIA Novosti archive, image #660791, Anatoliy Garanin, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

RIA Novosti archive, image #660791, Anatoliy Garanin, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Germany Is Weakened

Stalingrad was not only the bloodiest battle of WWII, it was also the biggest defeat ever for the German defense establishment. The 6th Army was wiped out, vital aircraft and personnel were lost, and Axis partners saw a nation no longer invincible, while the West lauded Soviet heroism.

Russian State Military Archive, Wikimedia Commons

Russian State Military Archive, Wikimedia Commons

On The Defensive

Germany’s strongman had been in power exactly a decade as Paulus prepared to surrender. Humiliated and furious, the Führer stayed silent, letting Joseph Goebbels read out a grudging admission the Reich was fighting defensively now. On this the German leader was very correct.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-F0316-0204-005, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-F0316-0204-005, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

England Can Breathe A Bit

Germany had lost an astonishing 200,000 or more men at Stalingrad by early 1943, on top of losing 50,000 of their ranks in late 1942 at the Battle of El Alamein in Egypt. With a weakened Germany still needing to fight on its eastern front, it was in no position to invade England.

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons

Fight For Survival

Over the next few weeks, Soviet forces managed to retake Kursk, Rostov-on-Don, and Kharkov. On February 18, Propaganda Minister Goebbels read his own speech that made the grim situation very plain. Germany, he said, would have to fight a “total war” for its very survival.

Bundesarchiv, Bild 119-2406-01, C-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bundesarchiv, Bild 119-2406-01, C-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

No Side Is Spared

In total, Axis powers—not just German, but also Italian, Romanian, and Hungarian forces—saw up to 1.5 million casualties or members captured, while the Red Army saw around 1 million members fatally lost, and many more wounded or missing. And then there were the civilians.

Relentless Destruction

On the first day of the battle, Germans dropped 1,000 tons of munitions, destroying 90% of the city’s housing. Within a week, tens of thousands of civilians may have lost their lives, a toll boosted by Stalin’s order to keep civilians in the city to build trenches and other defenses.

Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Harry S. Truman Library & Museum, Wikimedia Commons

In Hiroshima’s League

The battle’s civilian fatalities may have reached a quarter of a million for a city once home to a half-million people. One historian calculates that civilian fatalities were over 30% higher than those suffered in the atomic explosion at Hiroshima that helped force Japan’s surrender.

Shigeo Hayashi, Wikimedia Commons

Shigeo Hayashi, Wikimedia Commons

A Record Bloodbath

Another historian has said “the battle was the greatest military bloodbath in recorded history,” outstripping the horrendous toll of WWI battles at the Somme and Verdun. By the end, 99% of Stalingrad was destroyed, with just a few thousand civilians remaining amid the rubble.

RIA Novosti archive, image #602161, Zelma, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

RIA Novosti archive, image #602161, Zelma, CC-BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Towering Figure

Stalin passed away in 1953, and Stalingrad was renamed Volgograd in 1961 by reformist Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, to some patriotic opposition. In 1967, The Motherland Calls, Europe’s tallest statue, was erected in the city to celebrate the Soviet heroes of this great battle.

Thomas Taylor Hammond, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Taylor Hammond, Wikimedia Commons

The Course Of History

The Battle of Stalingrad dramatically punctured the powerful image of an unstoppable German expansion. Two leaders of ruthless ambition had unleashed a clash of gigantic forces, and a million or more lost lives later, this decisive battle would change the course of history.

You May Also Like:

Breaking Down WWII's Greatest Battles

The Most Infamous Battles Of WWI

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images