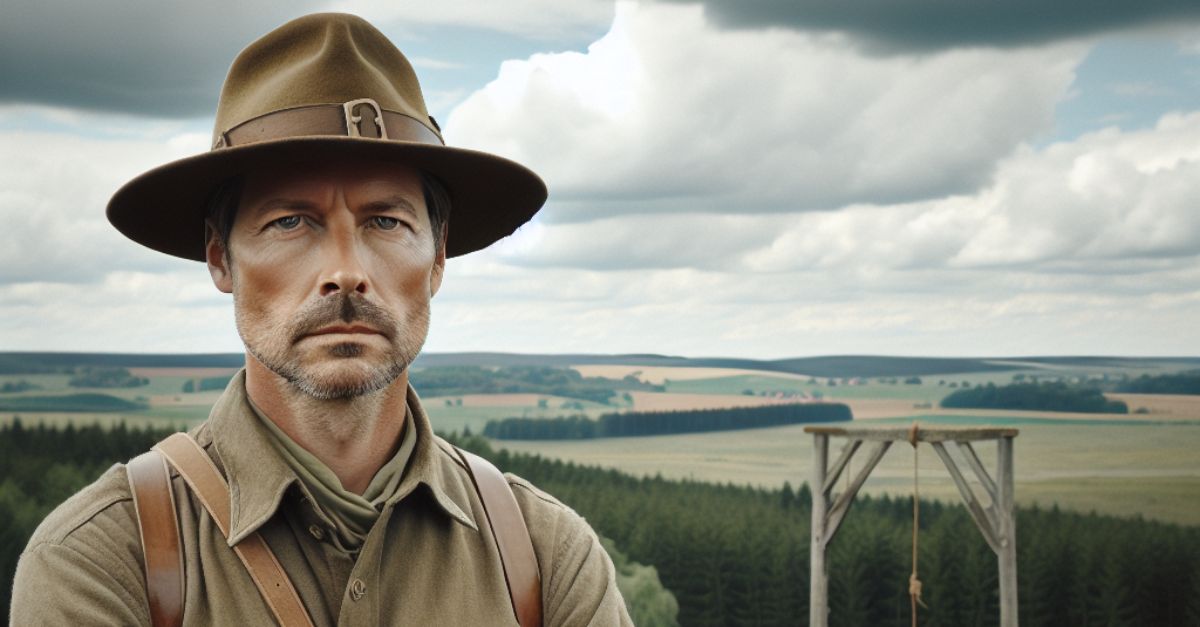

For centuries, the quiet hill near the town of Quedlinburg in Saxony-Anhalt appeared nothing more than an open field where cattle grazed peacefully. Beneath that calm surface, however, a darker story was waiting. What looked like an ordinary piece of countryside was, in reality, a burial ground shaped by fear and public judgment. When archaeologists began their excavation earlier this year, they expected routine documentation—not a window into an era when justice was brutal and swift. But what they discovered changed the meaning entirely. Hidden beneath generations of soil was a forgotten execution site from the 1600s filled with human remains.

The Unearthing Of A Forgotten Gallows Hill

The dig, conducted by the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt, began as part of a regional development project. While routine surveys are common before new construction, this one quickly took an unexpected turn. The archaeologists working on the site found at least 16 burials, each containing human skeletons arranged without care or ceremony. Some graves showed signs of hurried burial, suggesting executions carried out under grim and public circumstances. Researchers found that the site had been an official execution ground during the 17th century. Historical documents confirm that Quedlinburg once had its own gallows hill where the condemned were executed for crimes ranging from theft to witchcraft.

Archaeologists noted evidence of decapitations and other punishment marks on several skeletons, suggesting a time when execution served as both justice and public spectacle. As the excavation area widened, the team saw that many graves lacked coffins or any respectful preparation, with bodies placed directly into shallow pits that reflected how people labeled as criminals were treated after death. They also documented layered soil disturbances indicating the site was used repeatedly, possibly over decades, for carrying out capital sentences. Nearby tools, including rusted metal fragments likely tied to restraints or execution equipment, reinforced the picture of a space shaped by legal authority and intimidation.

Evidence Of Public Punishment

Based on the State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology of Saxony-Anhalt database, the graves likely belonged to people executed between 1650 and 1700. Many skulls bore clear-cut marks consistent with beheading. Others had injuries that matched descriptions of historical execution methods used in the region. The site’s layout also suggests it served as a place of punishment. In 17th-century Europe, gallows hills were often built along visible ridges or roads so travelers could see the warning they represented. Over time, these places of fear faded into farmland and left behind no sign of what once happened there.

Researchers believe the arrangement of the burials further supports the idea of a deliberately public setting. The graves were oriented irregularly, not in the orderly rows typical of churchyards or community cemeteries. Such disorder implies that the individuals buried there were excluded from traditional burial rites—another hallmark of execution grounds. Historical accounts from Saxony-Anhalt mention that gallows often remained standing for years, with executed bodies displayed as a cautionary message. While no wooden structures survived at the site, several hole patterns and soil discolorations suggest where posts or scaffolding may have once stood.

What The Findings Reveal About The Era

The discovery of 17th-century gallows hill in Germany provides rare physical evidence of early modern justice systems in central Europe. It offers researchers and other collaborating experts valuable insight into how communities balanced law and control during a period of great social change. Building on these recent findings, the team plans to analyze the remains further, using isotopic testing to trace origins and diet, along with carbon dating to refine the burial timeline. These expert methods could reveal who these people were, where they came from, and how their lives ended on this hill.

The excavation near Quedlinburg continues to offer rare glimpses into how justice and punishment were carried out centuries ago. All unearthed bones and tools add another piece to a story once thought lost. Beyond the bodies themselves, the site sheds light on shifting legal structures of the era. The mid-1600s were marked by the aftermath of the Thirty Years’ War, witch trials, and widespread social unrest. Punishment was severe, and execution grounds symbolized authority. The rediscovery of this hill demonstrates how deeply those practices shaped the landscape—even after memories of the events disappeared.