Dreams That Didn’t Land

Companies loved chasing the future, and plenty miscalculated. Big launches fizzled, odd designs confused buyers, and products slipped away before anyone really noticed.

Betamax (Sony, 1980s Peak)

Sony’s Betamax offered sharper picture quality than VHS, yet most consumers cared more about recording time. A typical tape could only hold one hour of content, leaving you mid-movie swap. When rental stores stocked more VHS titles, Betamax’s high standards couldn’t compete with convenience.

Sabung.hamster aka Everyone Sinks Starco aka BxHxTxCx, Wikimedia Commons

Sabung.hamster aka Everyone Sinks Starco aka BxHxTxCx, Wikimedia Commons

Atari 5200 (Atari, 1982)

Gamers expected the Atari 5200 to top its 2600 predecessor, but its oversized joysticks broke easily and lacked precision. Worse still, it couldn’t play existing Atari games. By the time Atari scrambled for fixes, Nintendo and Coleco had already captured players’s imaginations.

Daniel McConnell (TrojanDan) from Los Angeles, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Daniel McConnell (TrojanDan) from Los Angeles, USA, Wikimedia Commons

RCA SelectaVision (RCA, 1981)

RCA’s SelectaVision promised futuristic video playback using grooved discs, but discs wore down quickly and couldn’t record. The $500 million project ultimately failed when VHS offered a longer shelf life and recording capability. Within four years, RCA pulled the plug on the system.

RCA CED Selectavision VideoDisc Player SGT-100 Demo - Thrift Find! by Start To Continue

RCA CED Selectavision VideoDisc Player SGT-100 Demo - Thrift Find! by Start To Continue

ColecoVision Expansion Module #3 (Coleco, 1983)

Coleco tried to turn its hit console into a home computer with this add-on. Instead, the module constantly malfunctioned and felt underpowered compared to real computers. Consumers weren’t fooled, and Coleco’s attempt at bridging toys with productivity ended up as a short-lived gimmick.

Part 1: Is This ColecoVision Expansion Module #3 a Deader? by All Things ColecoVision

Part 1: Is This ColecoVision Expansion Module #3 a Deader? by All Things ColecoVision

Mattel Power Glove (Mattel/Nintendo, 1989)

The Power Glove looked revolutionary, inspired by sci-fi aesthetics and tied to the movie The Wizard. The issue? Its sensors barely responded, and this forced players to flail without control. Fewer than two games supported it, and its legacy remains more cultural curiosity than functional gaming tool.

Marcin Wichary, Wikimedia Commons

Marcin Wichary, Wikimedia Commons

Vectrex (Smith Engineering, 1982)

Unlike other consoles, the Vectrex came with its own vector-based screen with crisp visuals. The built-in display made the price steep, especially since cheaper color TVs were dominating households. With limited games and high costs, it faded quickly despite early buzz about innovation.

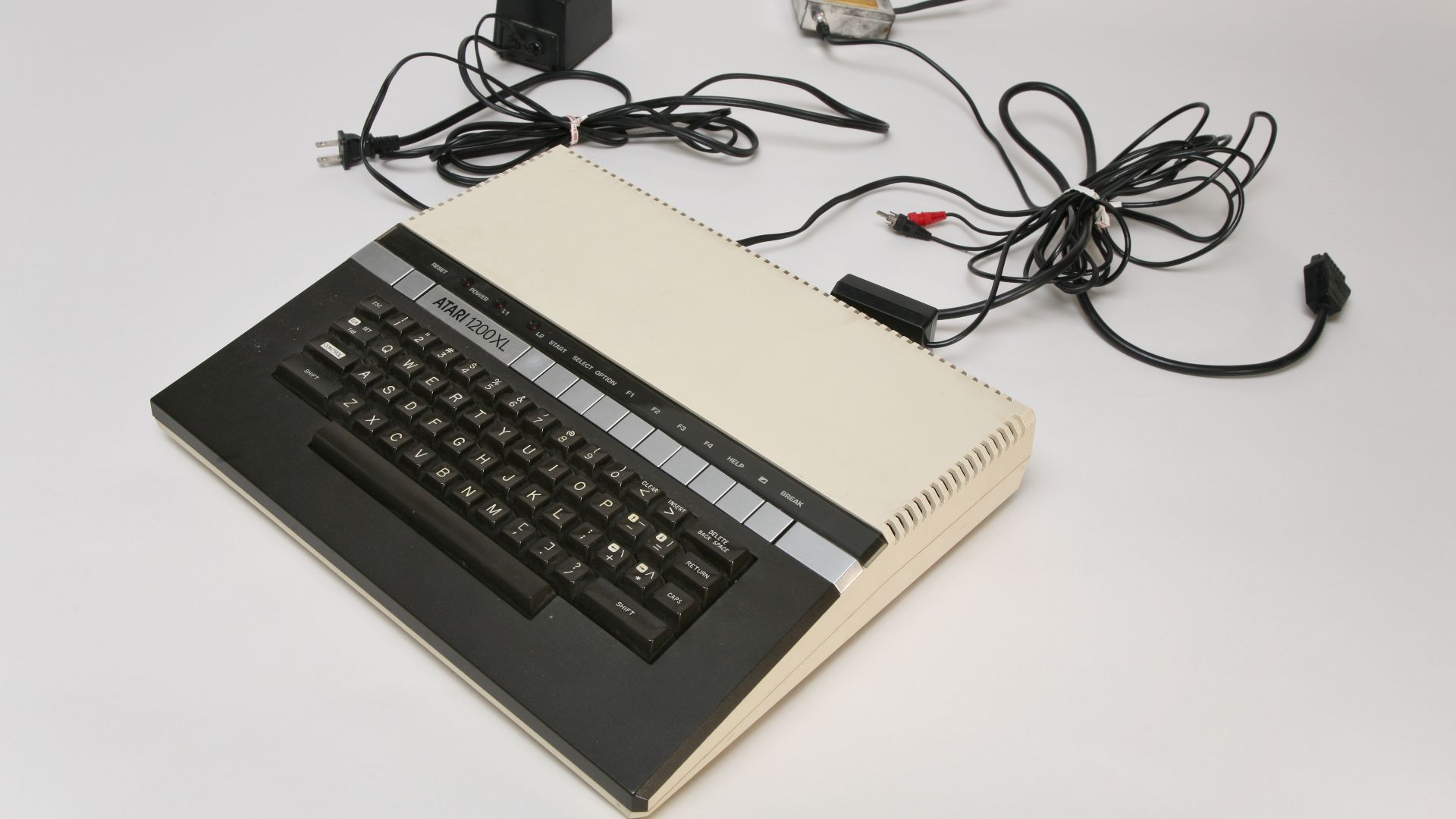

Atari 1200XL (Atari, 1983)

Atari touted the 1200XL as its next great home computer, but users quickly discovered many popular Atari programs wouldn’t run. Compatibility flaws, coupled with awkward design choices like a missing function key, left buyers frustrated. Within a year, the company abandoned the machine.

Daniel Schwen, Wikimedia Commons

Daniel Schwen, Wikimedia Commons

E.T. Atari 2600 Game (Atari, 1982)

Rushed out in just five weeks for the holiday season, E.T. became infamous for its confusing gameplay. Millions of unsold cartridges piled up, and thousands were buried in a New Mexico landfill. That notorious failure came to symbolize the entire 1983 video game crash.

taylorhatmaker, Wikimedia Commons

taylorhatmaker, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Sega Master System (Sega, 1986)

The Master System looked sleek and technically outperformed Nintendo’s NES. However, Sega lacked strong third-party games, and its marketing couldn’t rival Mario’s momentum. Though it found modest success in Europe and Brazil, in North America, it became an early footnote in console history.

Sega SG-1000 (Sega, 1983)

Launching the exact same day as Nintendo’s Famicom spelled disaster. Sega’s SG-1000 had clunky graphics, fewer games, and no real buzz. Nintendo gradually gained market dominance, and the SG-1000 slipped quietly into obscurity, remembered mainly as Sega’s awkward first step.

IBM PCjr (IBM, 1984)

Hyped as the family-friendly PC, IBM’s PCjr came with a terrible “chiclet” keyboard that made typing a nightmare. Worse, it couldn’t run most IBM software. Consumers balked at the price, schools avoided it, and within two years, IBM pulled the plug.

Marcin Wichary, Wikimedia Commons

Marcin Wichary, Wikimedia Commons

Commodore Plus/4 (Commodore, 1984)

Commodore tried to leap beyond its hit C64 with the Plus/4, but the gamble backfired. It wasn’t compatible with the massive C64 library, leaving owners with practically no games. Add weaker graphics, and the Plus/4 ended up gathering dust instead of fans.

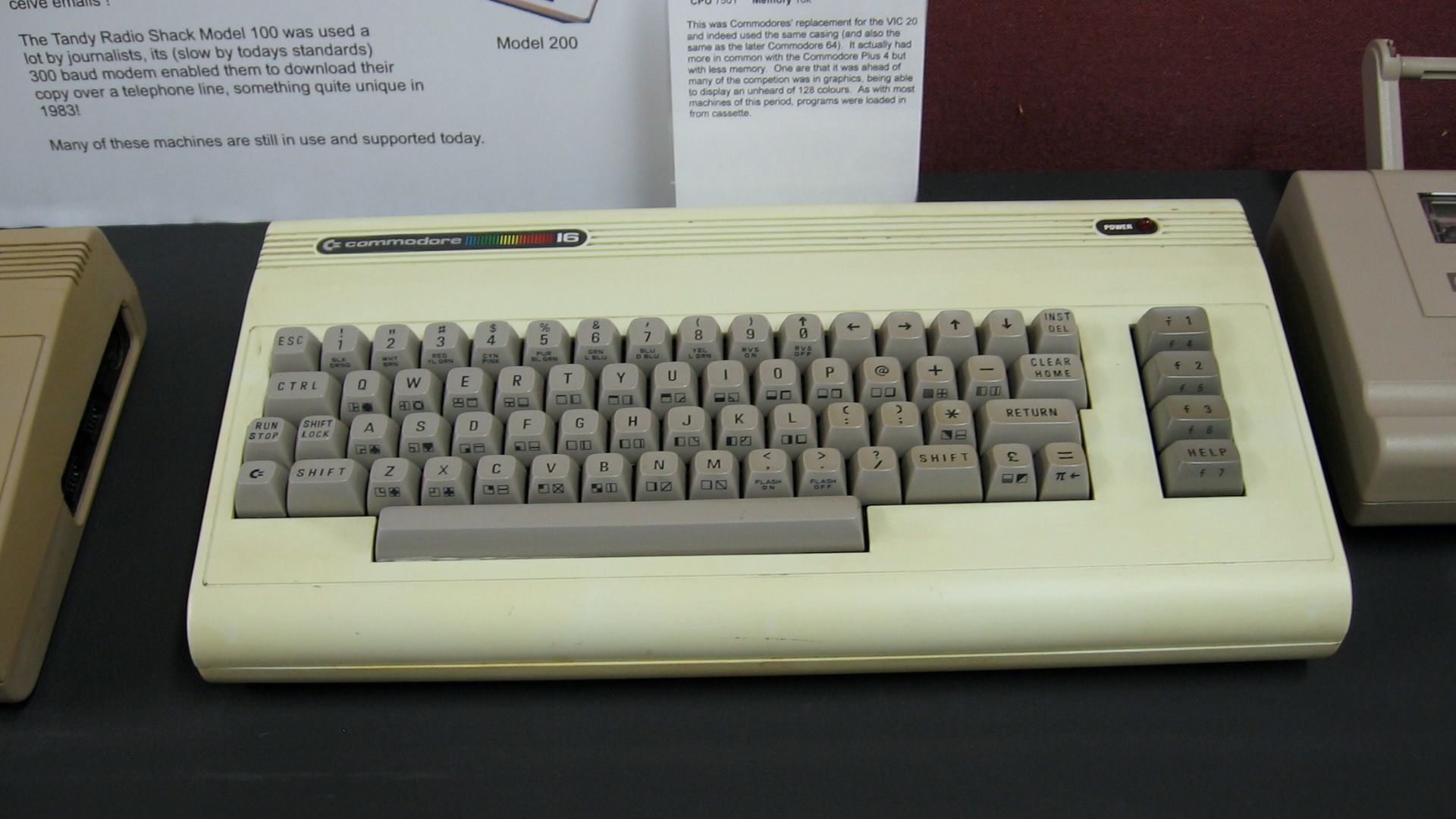

Commodore 16 (Commodore, 1984)

The Commodore 16 appeared to be a budget option, but it came with stripped-down hardware and limited software support. Casual users ignored it, while serious gamers stuck with the C64. By the following year, the 16 was off shelves entirely.

Marcin Wichary from San Francisco, U.S.A., Wikimedia Commons

Marcin Wichary from San Francisco, U.S.A., Wikimedia Commons

Mattel Aquarius (Mattel, 1983)

The Mattel brand rushed the Aquarius into stores, and boy, did it show. Its graphics felt dated, and its software lineup looked thin compared to rivals. The system quickly earned the nickname “the system for the seventies,” despite being a supposed eighties release.

TI-99/4A (Texas Instruments, 1981)

Texas Instruments spent millions advertising the TI-99/4A, but a steep price tag scared buyers. Even when prices dropped, the software catalog stayed weak. Competitors like Commodore ate its lunch, and by 1983, Texas Instruments had left the home computer race completely.

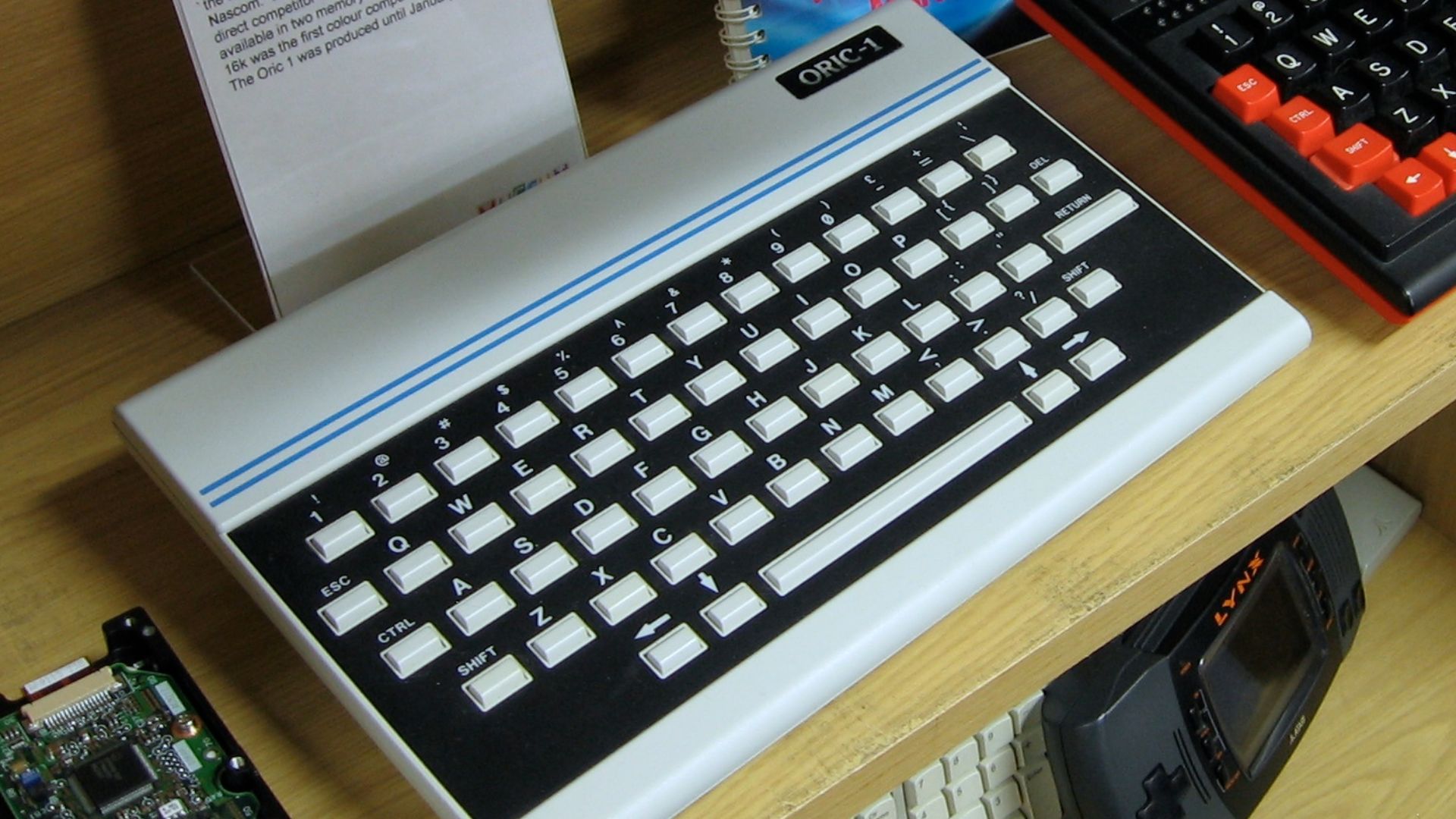

Oric-1 Computer (Tangerine, 1983)

Across the pond, the Oric-1 tried to compete with the Sinclair ZX Spectrum. It looked promising, but it crashed frequently and shipped with buggy software. While a few loyal fans stuck around, reliability issues kept it from ever breaking into the mainstream.

Marcin Wichary from San Francisco, U.S.A., Wikimedia Commons

Marcin Wichary from San Francisco, U.S.A., Wikimedia Commons

Tandy TRS-80 Pocket Computer (Tandy/Sharp, 1980)

Imagine a calculator-sized “computer” that cost hundreds of dollars but barely did more than basic math and programming. That was Tandy’s pitch. For hobbyists, it was a novelty. Most consumers saw it as a limited, niche tool with minimal appeal.

Shelby Jueden, Wikimedia Commons

Shelby Jueden, Wikimedia Commons

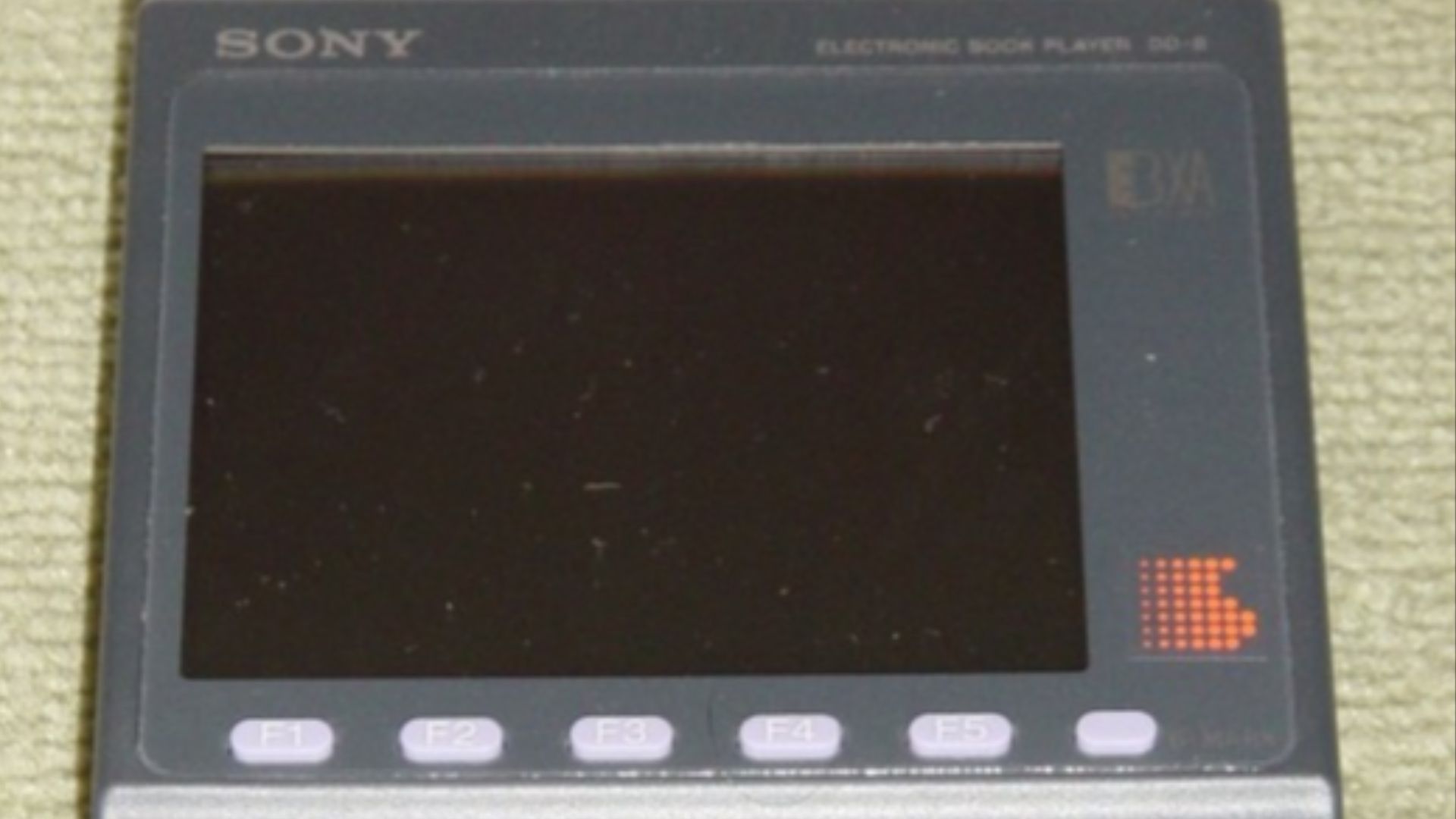

Sony Data Discman (Sony, 1989)

Sony thought people would love carrying reference books on mini-discs. In practice, the Data Discman was too expensive, had a limited number of titles, and displayed clunky text on a tiny screen. E-books were still decades from catching fire, leaving this device a little too early.

Lawrie at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Lawrie at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

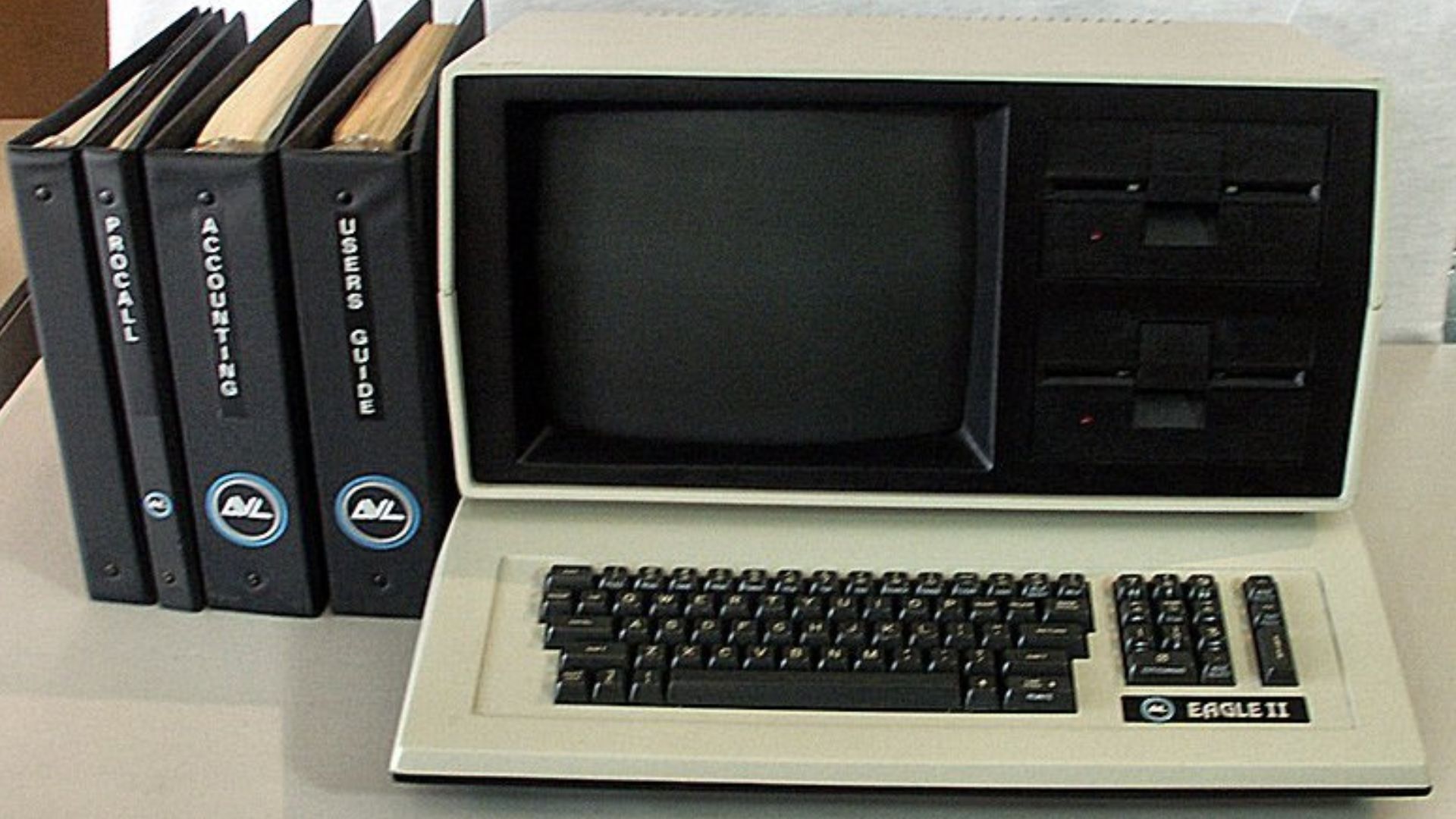

Eagle PC (Eagle Computer, 1980s)

When Eagle tried to stand out by making an IBM clone, it charged more while offering nothing unique. Consumers asked, “Why not just buy the real IBM?” Because of this, sales dried up quickly to prove that imitation without innovation rarely pays off in the tech industry.

Taawisuomainen, Wikimedia Commons

Taawisuomainen, Wikimedia Commons

Kodak Disc Camera (Kodak, 1982)

Kodak thought a disc-shaped film cartridge would simplify photography. It did, but the negatives were tiny—producing grainy, washed-out prints. Consumers expecting the set Kodak quality were disappointed. By the late 80s, the format disappeared, and this left behind millions of blurry vacation snapshots in family albums.

Nimslo 3D Camera (Nimslo, 1980)

The Nimslo snapped four photos at once to create lenticular 3D prints. The catch? Processing required special labs, and each print cost a small fortune. Consumers lost interest quickly, and the 3D camera trend fizzled almost as soon as it started.

John Alan Elson, Wikimedia Commons

John Alan Elson, Wikimedia Commons

PXL-2000 Camcorder (Fisher-Price, 1987)

A camcorder for kids sounded fun, but the PXL-2000 recorded grainy black-and-white video onto audio cassettes. The quality resembled security footage more than family movies. At $170, parents expected better, and the toy earned its place as a quirky tech misfire.

Bullenwächter, Wikimedia Commons

Bullenwächter, Wikimedia Commons

VideoFloppy (Sony, 1980s)

Sony attempted to use floppy disks for analogue still images, referring to it as the VideoFloppy. But the pictures looked fuzzy, storage was limited, and digital photography was already on the horizon. By the 1990s, the format was obsolete, another stepping stone lost to history.

Sinclair C5 (Sinclair Research, 1985)

Billed as the future of commuting, this electric tricycle topped out at 15 miles per hour. Drivers sat so low that trucks barely saw them. Combine that with poor battery range, and the C5 quickly became a punchline instead of a revolution.

Grant Mitchell, Wikimedia Commons

Grant Mitchell, Wikimedia Commons

Rabbit Telepoint (Hutchison Telecom, 1989)

Before true mobile phones, Rabbit offered cordless handsets you could carry—if you stayed within range of public base stations. Calls only worked near designated hotspots, making it nearly impossible to use on the go. By the early 90s, cellular networks buried the Rabbit system for good.

The original uploader was Jmb at English Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

The original uploader was Jmb at English Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

Barbie Typewriter (Mattel, 1980s)

A pastel typewriter sounds adorable, but functionality was lacking. Keys jammed, print quality looked sloppy, and it offered none of the reliability of real machines. Kids found it frustrating, and parents felt duped. Collectors may smile today, but back then, it was pure disappointment.

X mas calendar Nr.13: trying on my vintage Barbie typewriter by Vintagegaudi

X mas calendar Nr.13: trying on my vintage Barbie typewriter by Vintagegaudi

DeLorean DMC-12 (DeLorean Motor Co, 1981)

The stainless steel body and gull-wing doors screamed cool, especially after Back to the Future. But its underpowered V6 and $25,000 price tag crushed sales. Add founder John DeLorean’s legal troubles, and fewer than 9,000 cars ever reached customers before the company's bankruptcy.

Coleco Adam (Coleco, 1983)

Coleco’s follow-up to its successful console looked promising, as it bundled a printer and a word processor. Reality? The printer was deafening, crashes were constant, and prices soared. Parents who bought one discovered homework disappeared faster than progress. Within two years, Coleco was out of the computer game.

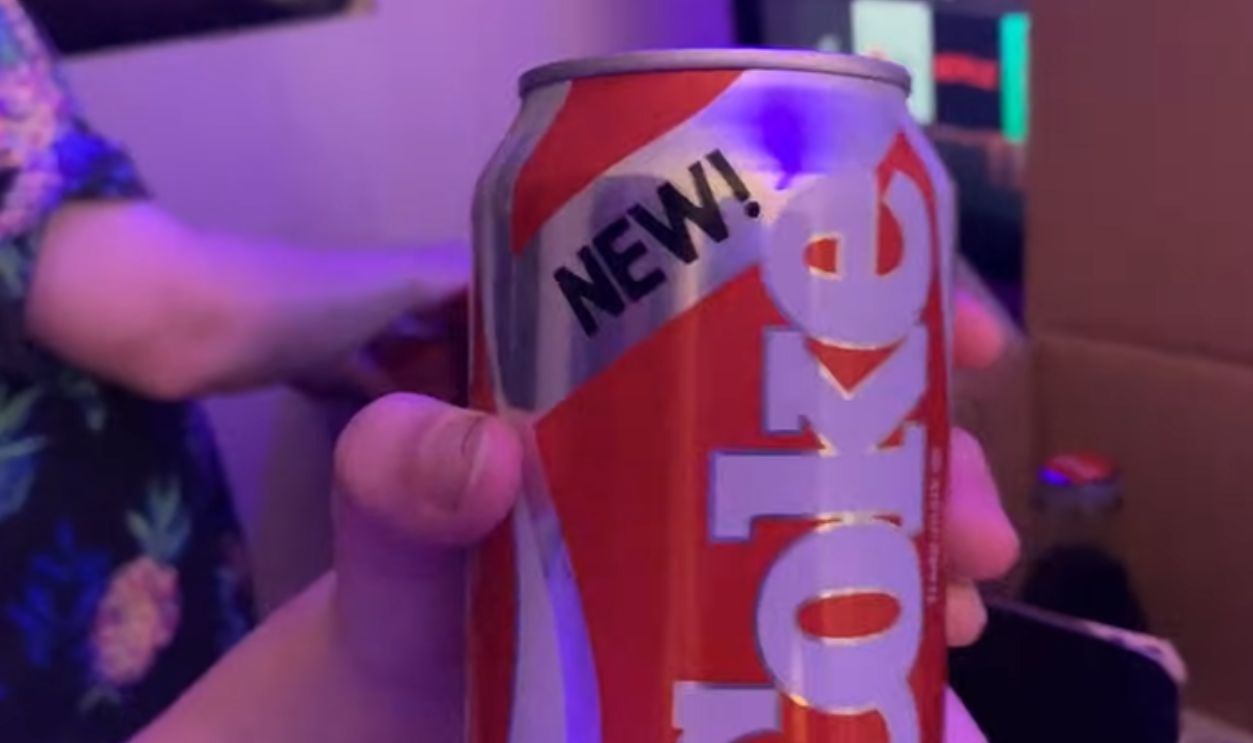

New Coke (Coca-Cola, 1985)

Coca-Cola decided to sweeten its formula to battle Pepsi’s rising popularity. The backlash was instant—hotlines jammed, protests erupted, and this prompted the return of the “classic” Coke in just 79 days. Ironically, the blunder reinforced consumer loyalty, making New Coke one of the most famous product misfires ever.

Drinking Coke from 1985! Special Stranger Things edition! by Danica DeCosto

Drinking Coke from 1985! Special Stranger Things edition! by Danica DeCosto

Gizmo Drink (Unknown, 1989)

An alcoholic soda before “hard” beverages had a market, but Gizmo confused shoppers. Was it beer? Was it soda? Branding never nailed an identity, and its taste didn’t help. By the following year, distributors stopped carrying it, and this ended its fizz before it foamed.

MOUNTAIN DEW GREMLINS Ad (2021) Gizo Caca Horror by JoBlo Horror

MOUNTAIN DEW GREMLINS Ad (2021) Gizo Caca Horror by JoBlo Horror

Pepsi AM (PepsiCo, 1989)

Marketed as a morning cola with extra caffeine, Pepsi AM aimed to replace coffee. Few Americans wanted soda at breakfast, and the product barely lasted a year. Pepsi scrapped it quickly. Sometimes, the time of day matters more than marketing hype.

Max Headroom Soda (Coca-Cola Licensed, 1980s)

Coca-Cola slapped cult TV character Max Headroom on cans, betting quirky branding would move product. Consumers weren’t impressed, especially when the taste underdelivered. Unlike Max’s futuristic digital persona, the soda had no staying power. The project fizzled out faster than the character’s catchphrases.

Coca-Cola Max Headroom | Max Headroom Coke commercials by Zona C

Coca-Cola Max Headroom | Max Headroom Coke commercials by Zona C

Smokeless Cigarettes (RJ Reynolds, 1988)

Called “Premier,” these heated sticks released nicotine without smoke. They cost more, tasted worse, and required special lighters. Smokers hated them, non-smokers didn’t care, and the experiment burned through nearly a billion dollars before Reynolds admitted defeat in one of tobacco’s biggest flops.

Electronic Belt (Various Brands, 1980s)

Infomercials promised that strapping on a vibrating belt would melt fat while you relaxed. In reality, no one got slimmer sitting still. Word spread fast that it was a gimmick, and these belts ended up gathering dust in closets nationwide.

Vintage Vibrating Exercise Belt | RETURN IT OR BURN IT by Good Mythical Morning

Vintage Vibrating Exercise Belt | RETURN IT OR BURN IT by Good Mythical Morning

Sanyo Portable 8-Track Player (Sanyo, 1980s)

By the 1980s, cassettes had largely replaced 8-tracks, but Sanyo stubbornly continued to release a portable 8-track player. It was bulky, and consumers had moved on. The timing was terrible—this player became a last gasp for a dying format, not a revival.

Sanyo 8 Track Player/Recorder RD-8020 by bluenazz

Sanyo 8 Track Player/Recorder RD-8020 by bluenazz

Apple Lisa (Apple, 1983)

Apple’s Lisa introduced a graphical interface years before Windows, but it came at a staggering $10,000 price tag. Businesses found it too slow for the price, while home users couldn’t afford one. Only 10,000 units sold, making it Apple’s most expensive lesson.

Sony Beta Movie Recorder (Sony, 1983)

Sony’s Betamovie promised the future in one handheld camcorder. Unfortunately, playback required a separate deck. Families hated lugging around extra gear just to watch home movies. Despite being the first consumer camcorder, it couldn’t overcome convenience issues and quickly lost ground to VHS.

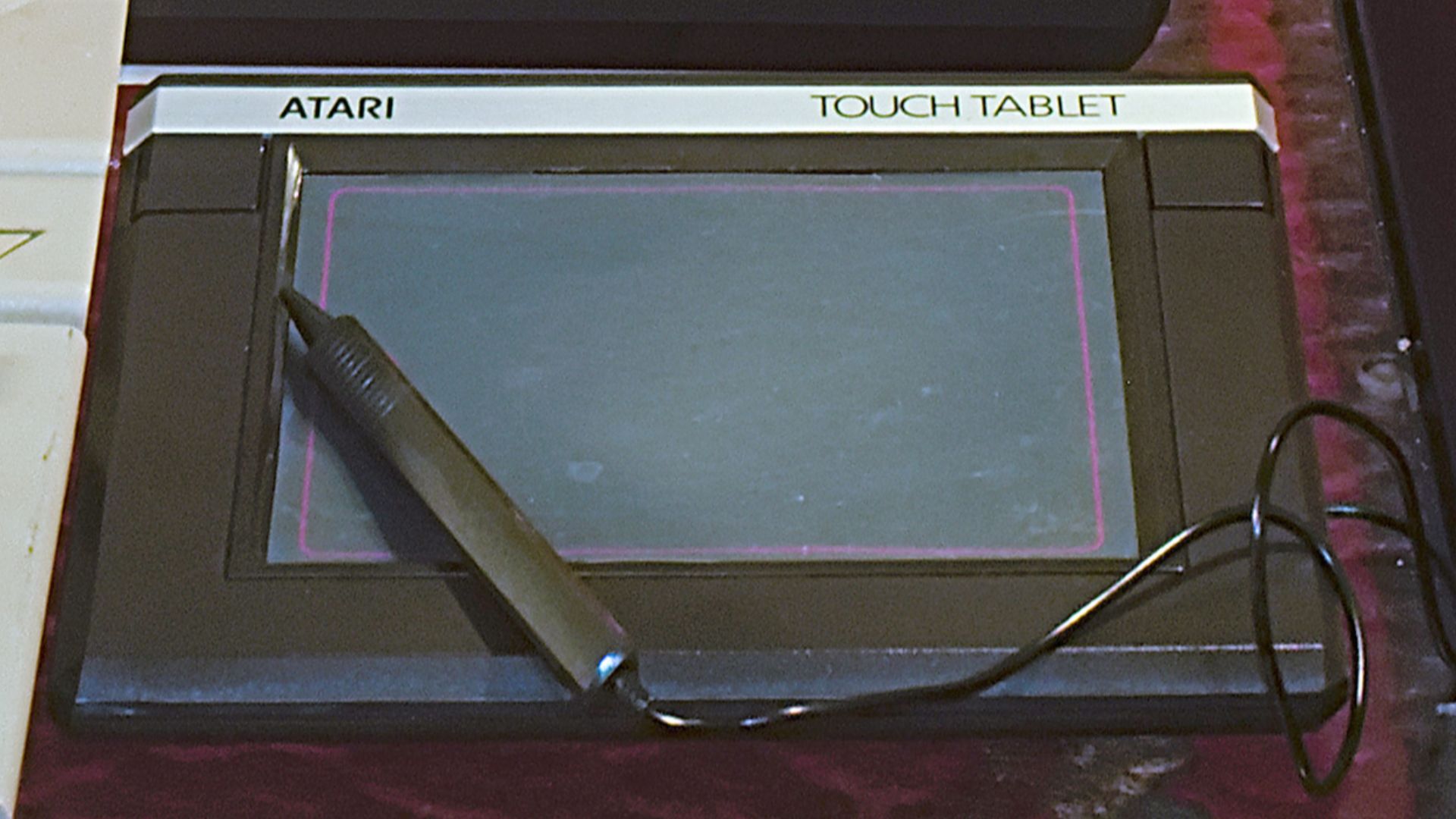

Atari CX77 Touch Tablet (Atari, 1984)

Years before iPads, Atari tried a pressure-sensitive tablet for drawing. Precision was poor, and software support was scarce. Most games even ignored it. Instead of inspiring digital artists, it frustrated kids. By 1985, Atari shelved it, and touchscreens wouldn’t shine for decades.

Terry Ross from Corpus Christi, Texas, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Terry Ross from Corpus Christi, Texas, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Digital Audio Tape (DAT) (Sony, 1987)

DAT wowed audiophiles with studio-quality sound, but each tape cost more than CDs. Record labels also feared piracy because it allowed perfect digital copies. Between lawsuits, high prices, and the rise of compact discs, DAT players never moved beyond niche recording studios.

Polaroid Instant Video System (Polaroid, 1980s)

Polaroid attempted to bring its instant-photo magic to video. Instead of crisp footage, families got blurry, color-shifting clips that cost a fortune to record. The disappointment stung. By the 80s, Polaroid’s gamble fizzled, proving video wasn’t ready for instant gratification.

Leif Skandsen, Wikimedia Commons

Leif Skandsen, Wikimedia Commons

Automated Electric Tie Rack (Various, 1985)

The electric tie rack spun neckties at the push of a button, but motors jammed, batteries died fast, and it rarely fit more than a handful of ties. Shoppers realized hanging ties on a hook worked just as well—without the noise.

Automatic Tie Rack by Brookstone

Automatic Tie Rack by Brookstone

ThighMaster Precursor Devices (Various, 1980s)

Long before Suzanne Somers’s ThighMaster craze, awkward exercise gadgets promised toned legs. Most pinched, squeaked, or failed to provide real resistance. Home users gave up fast, and this left the prototypes forgotten. Only in the 90s did a streamlined version finally make a splash.

First Time Trying the Suzanne Somers Thigh Master! Does it Work? by Our Gen X Life

First Time Trying the Suzanne Somers Thigh Master! Does it Work? by Our Gen X Life

AT&T VideoPhone 2500 (AT&T, 1988)

This phone featured a grainy video screen, which offered families their first glimpse of “Jetsons-style” calls. Sadly, the novelty ended quickly. The hardware cost over $1,000, and the picture quality looked terrible. Most people felt awkward on camera.

Marcin Wichary, Wikimedia Commons

Marcin Wichary, Wikimedia Commons

Sony Watchman (Sony, 1982, Early Models)

The Watchman put live TV in your palm with a tiny black-and-white screen. The reception often cut out, and viewing sports or news on a two-inch display strained eyes. While futuristic in idea, its first innovations never became daily companions for television fans.