Cosmic Blade Mystery

Something strange rested on the boy king's mummified thigh. The metal gleamed impossibly bright for its age, and experts puzzled over it for decades until they realized the weapon came down in celestial fire.

Boy King

A nine-year-old kid suddenly becomes the ruler of the most powerful civilization on Earth. That was Tutankhamun around 1333 BC. The young pharaoh inherited a throne during Egypt's tumultuous 18th Dynasty, a period marked by religious upheaval and political instability.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Sudden Death

At approximately 19 years old, Tutankhamun died, leaving historians puzzled for millennia. Modern CT scans and DNA analysis suggest he suffered from multiple health issues, including a severe leg fracture, malaria, and genetic disorders from generations of royal inbreeding.

Hasty Burial

Evidence suggests Tutankhamun's funeral was rushed, quite unusual for Egyptian royalty. His tomb—designated KV62 by archaeologists—is remarkably small compared to other royal burial sites in the Valley of the Kings, possibly because it wasn't originally intended for him. The burial chambers show signs of hurried decoration.

EditorfromMars, Wikimedia Commons

EditorfromMars, Wikimedia Commons

Lost Centuries

For over 3,200 years, Tutankhamun's tomb lay hidden beneath approximately 30 feet of limestone rubble and flood debris from subsequent excavations. The entrance to Ramesses VI's tomb, constructed about 150 years after Tut's demise, inadvertently protected the boy king's resting place by covering it with workers' huts and excavation waste.

Tobeytravels, Wikimedia Commons

Tobeytravels, Wikimedia Commons

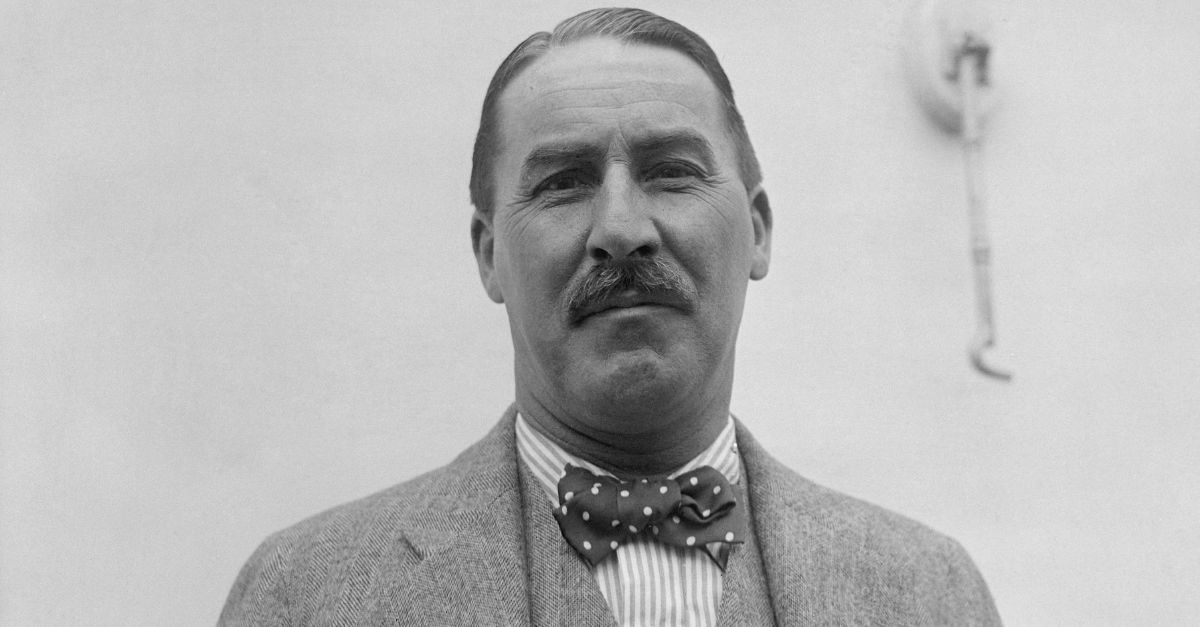

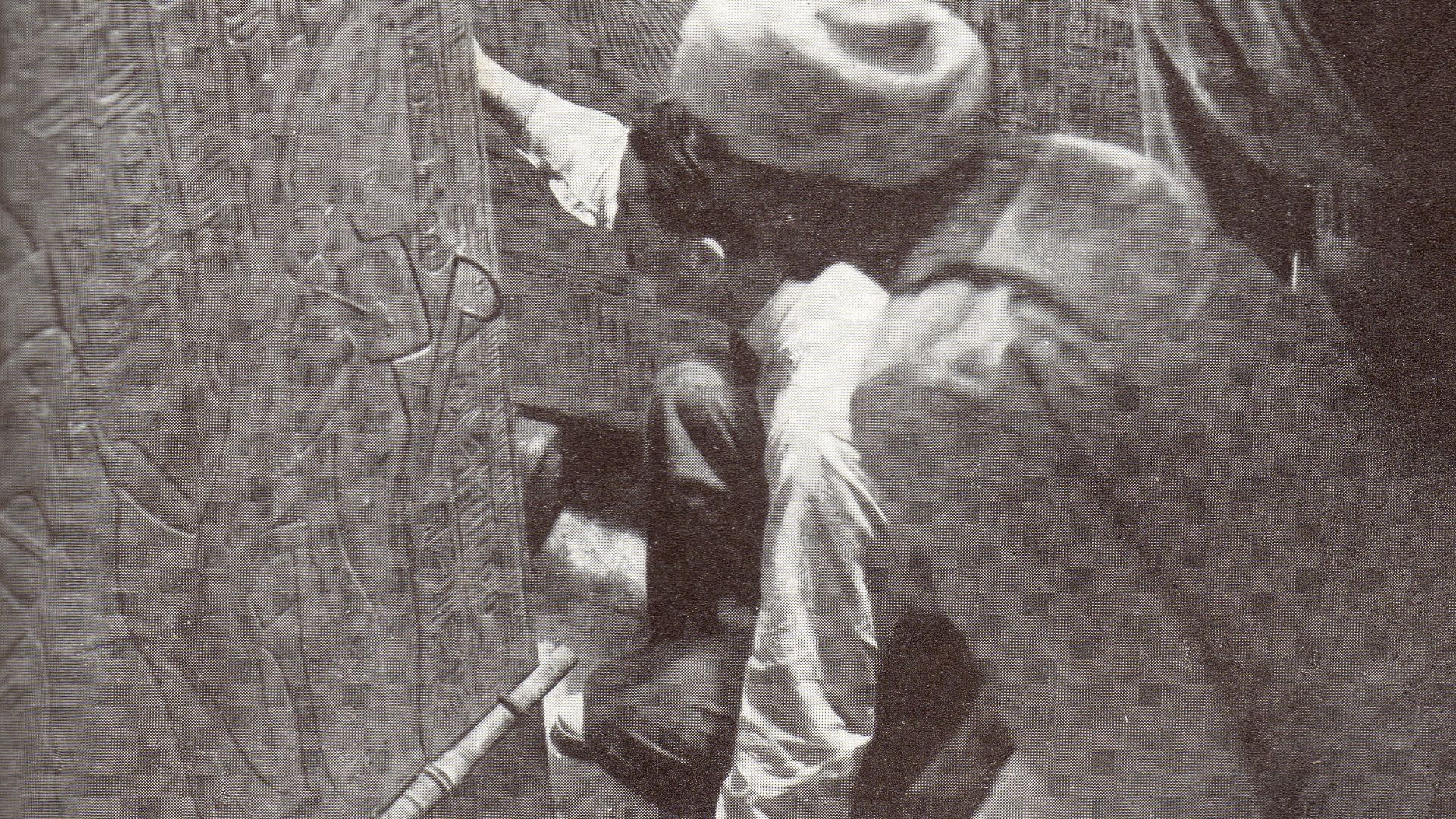

Carter's Quest

Howard Carter was stubborn, some would say obsessed. The British archaeologist spent five grueling years methodically digging through the Valley of the Kings, systematically removing tens of thousands of tons of debris down to bedrock. His wealthy patron, Lord Carnarvon, grew frustrated with the lack of results and mounting expenses.

Cassowary Colorizations, Wikimedia Commons

Cassowary Colorizations, Wikimedia Commons

November Discovery

On November 4, 1922, a water boy (according to local legend) or a workman tripped over something below the sand. Carter's team uncovered a staircase descending into darkness, and at the bottom stood a sealed doorway bearing royal seals.

Harry Burton, Wikimedia Commons

Harry Burton, Wikimedia Commons

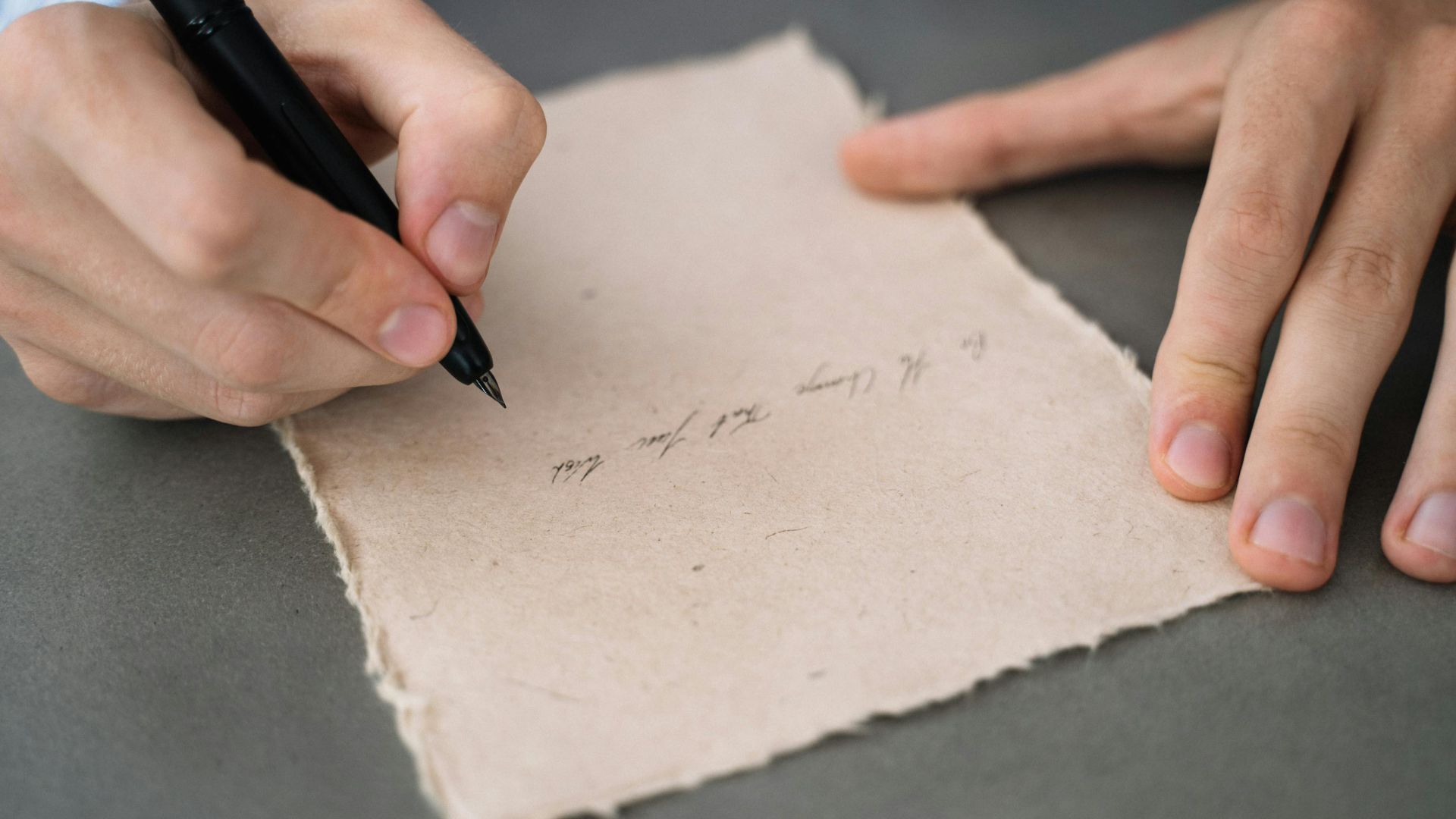

Telegram

Carter's hands probably trembled as he sent a telegram to Carnarvon in England: "Have made wonderful discovery in Valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact”. Three weeks of agonizing waiting followed before Carnarvon arrived, and they could finally breach the entrance.

Golden Treasures

"Can you see anything?" Carnarvon asked anxiously as Carter peered through a small hole on November 26, 1922. "Yes, wonderful things!" Carter's famous reply hardly captured the reality: stacked golden chariots, animal-shaped beds overlaid with gold, alabaster vessels, and treasures packed floor-to-ceiling.

Harry Burton, Wikimedia Commons

Harry Burton, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

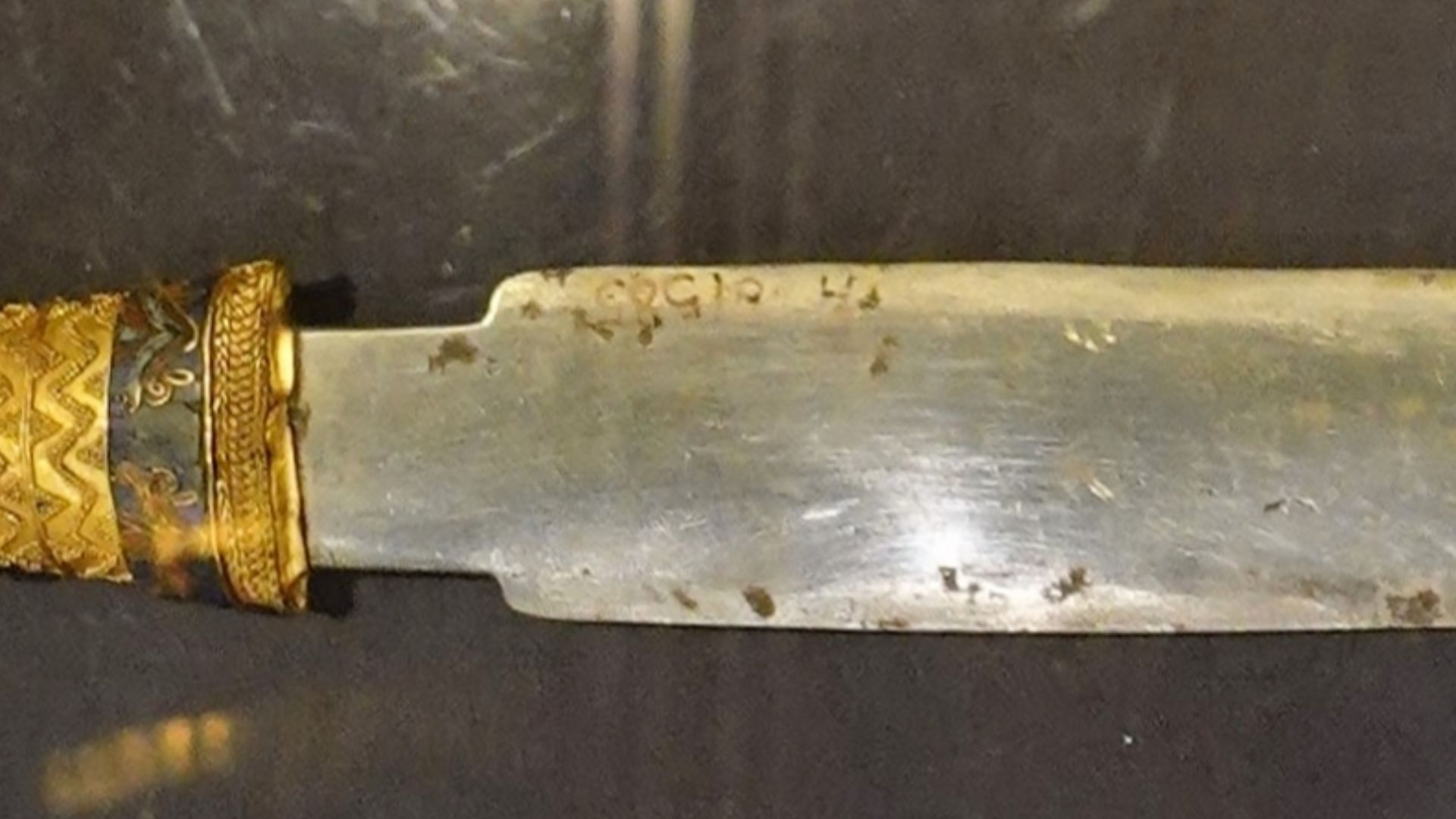

Iron Anomaly

Wrapped within the linen bandages around Tutankhamun's mummified body, Carter discovered an iron dagger with a golden hilt and ornate sheath, positioned on the pharaoh's right thigh. The blade measured just over 13 inches long and gleamed as if newly forged despite being over three millennia old.

Bronze Age

Here's the problem. Tutankhamun passed away around 1323 BC, smack in the middle of the Bronze Age. During this period, metalworkers across the Mediterranean had mastered copper and bronze production but hadn't yet figured out iron smelting. The Iron Age wouldn't begin in Egypt for another six or seven centuries.

Smelting Absent

Ancient Egyptians simply didn't have the technology to extract iron from terrestrial ores during Tutankhamun's lifetime. Smelting iron requires temperatures exceeding 1,500°C (2,700°F), far beyond what Bronze Age furnaces could achieve. Egyptian hieroglyphics from this period called iron "ba-en-pet," suggesting they recognized its celestial origins.

Windmemories, Wikimedia Commons

Windmemories, Wikimedia Commons

Iron Paradox

The dagger's pristine condition baffled researchers for decades. Every other ancient iron artifact from this era had corroded into unrecognizable rust-covered lumps, yet Tut's blade remained remarkably shiny. Early theories in the 1960s and 1970s suggested the high nickel content indicated meteoritic origin, but the testing methods were inconclusive.

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

Scientific Testing

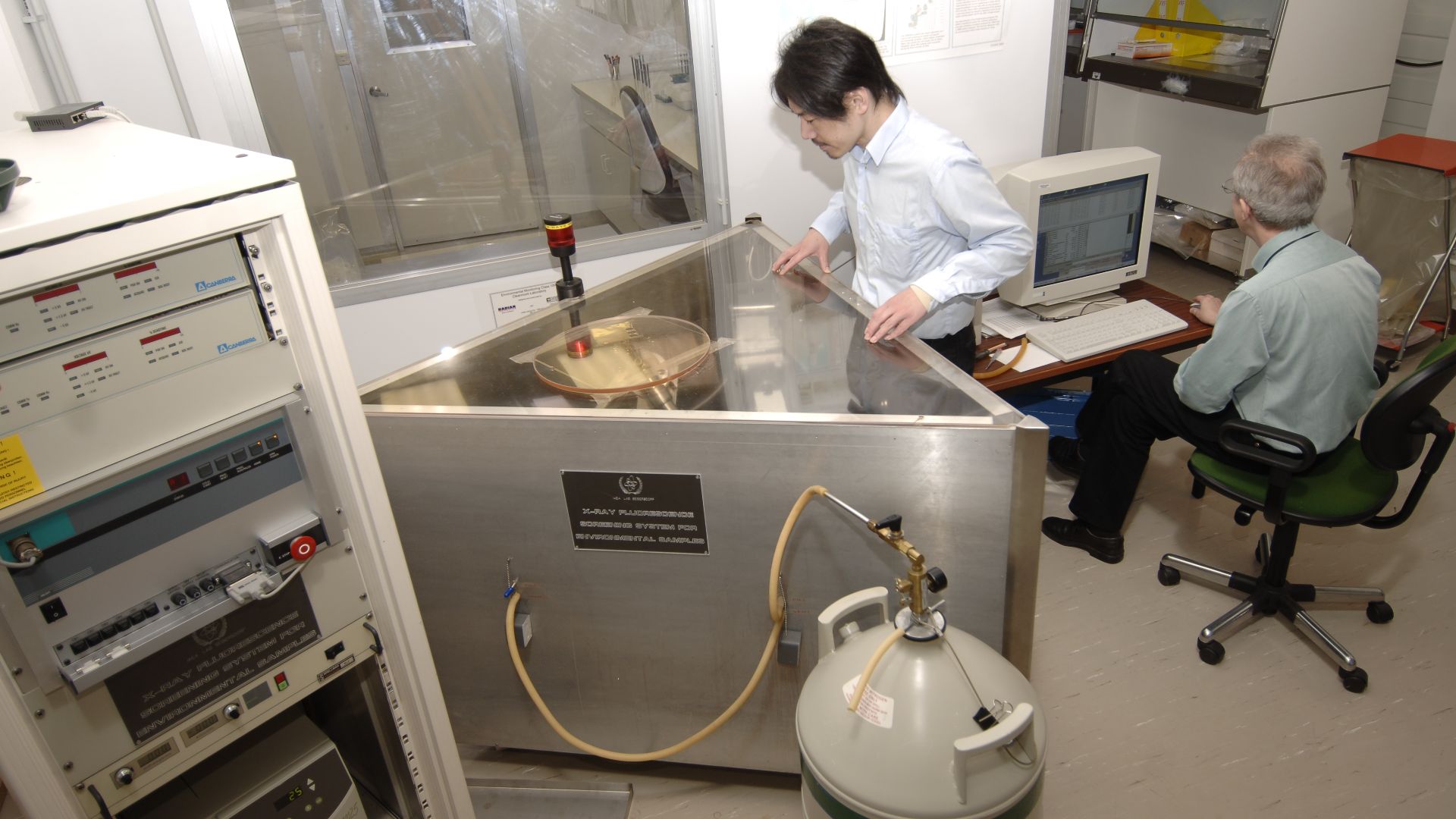

In 2016, Italian and Egyptian researchers finally brought modern technology to bear on the ancient weapon. Using portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry, a non-destructive technique that doesn't harm precious artifacts, they could analyze the blade's chemical composition without cutting or damaging it.

IAEA Imagebank, Wikimedia Commons

IAEA Imagebank, Wikimedia Commons

Nickel Signature

Well, the results were definitive: the blade contained 10.8% nickel and 0.58% cobalt. This chemical fingerprint became the smoking gun. Terrestrial iron ore mined from Earth's crust contains less than 4% nickel—usually under 1%—because during our planet's formation, nickel sank toward the molten core along with iron.

Materialscientist (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Materialscientist (talk), Wikimedia Commons

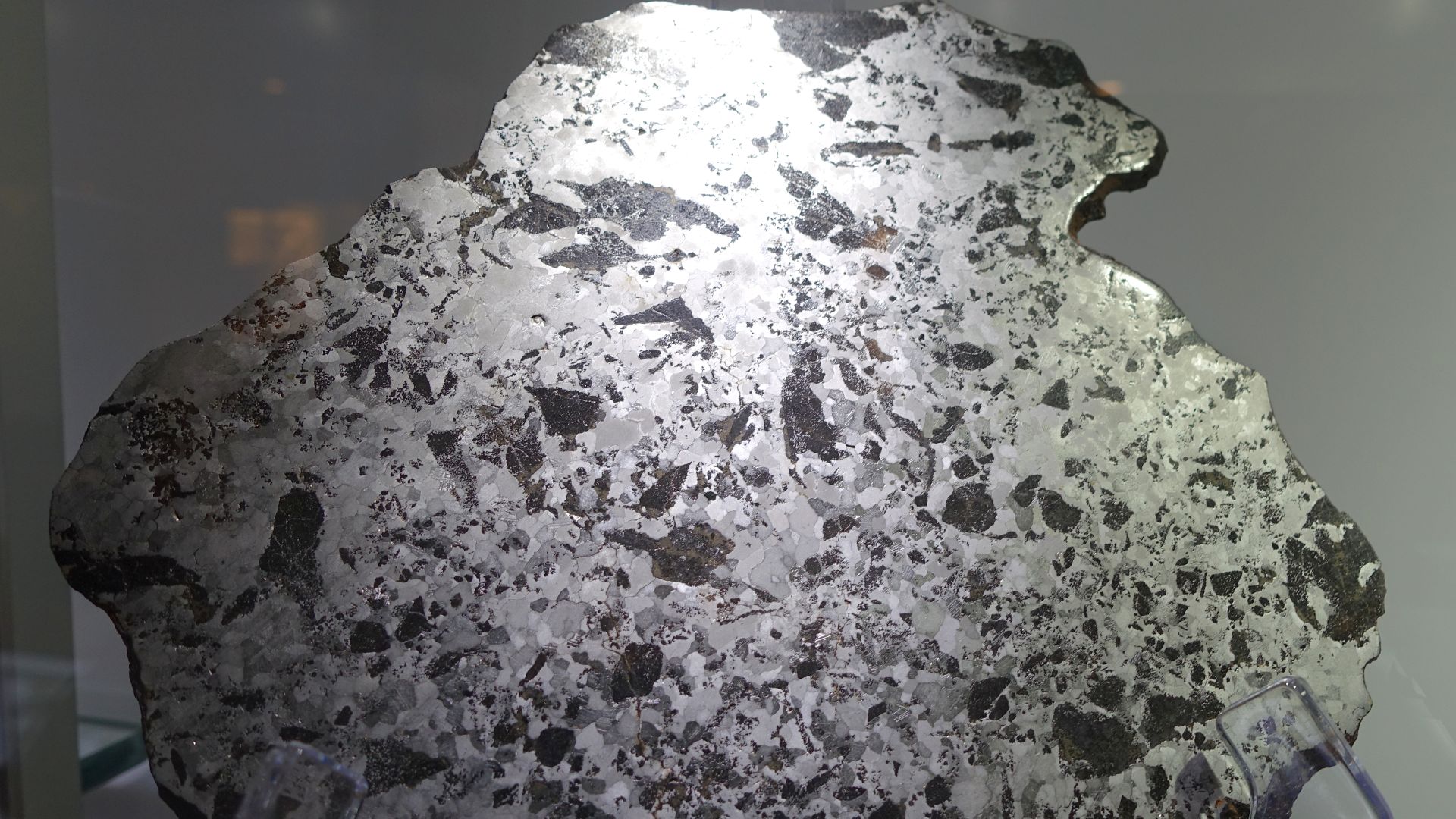

Meteorite Confirmed

The team's analysis matched the dagger's composition almost perfectly with the Kharga meteorite, discovered 150 miles west of Alexandria near Mersa Matruh, an ancient seaport. This iron meteorite, part of an ancient meteor shower, had fallen in Egypt's Western Desert millennia ago.

Space Origins

These weren't just any space rocks. They were remnants from the violent birth of our solar system. Iron meteorites form in the cores of planetesimals, small proto-planets that smashed into each other during the chaotic period 4.5 billion years ago, when our cosmic neighborhood was still taking shape.

NASA Hubble, Wikimedia Commons

NASA Hubble, Wikimedia Commons

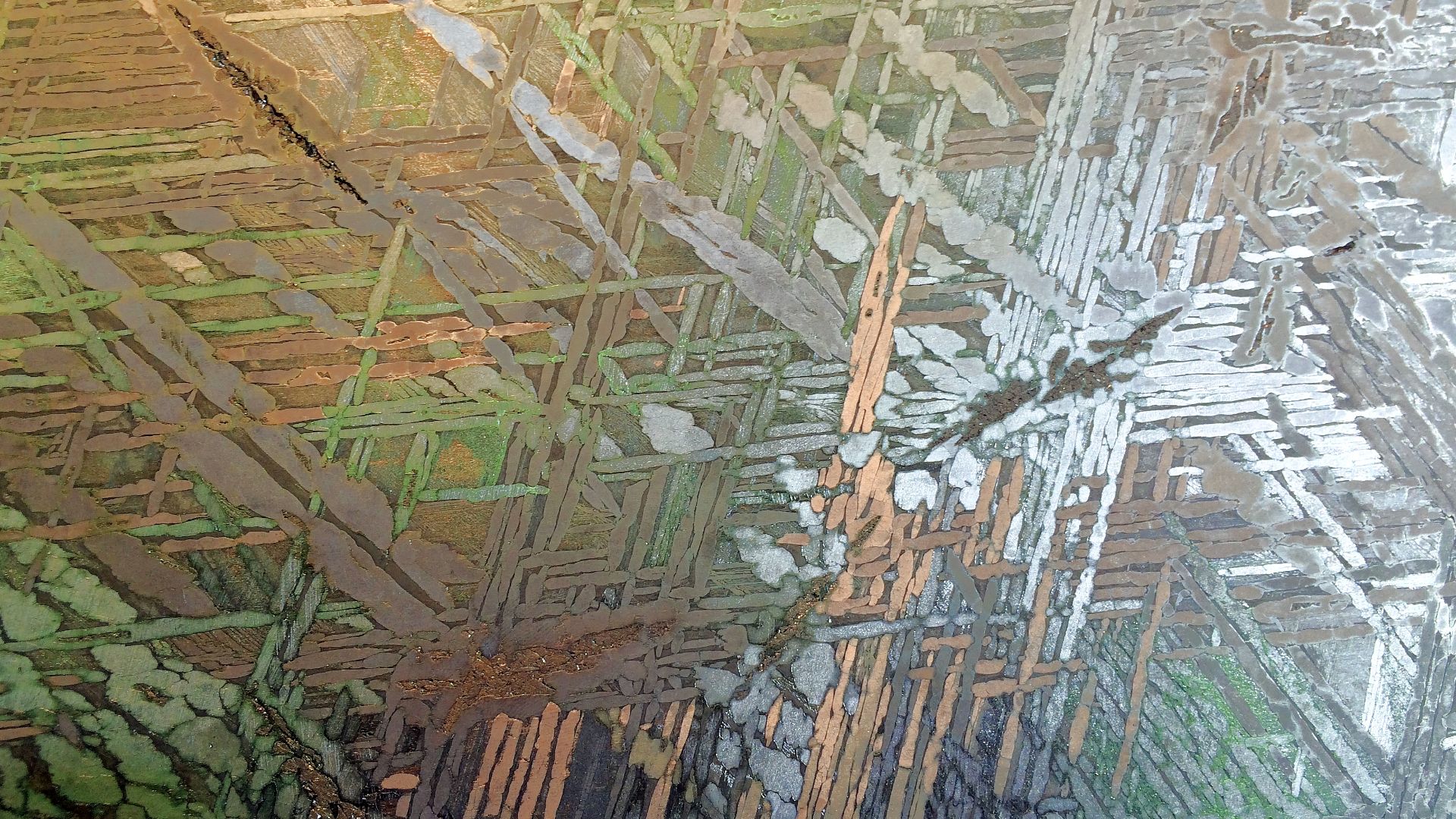

Widmanstatten Pattern

Japanese researchers from the Chiba Institute of Technology made another important discovery in 2020 when they examined the blade at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. They detected a Widmanstatten pattern, a distinctive crystalline structure visible only in meteoritic iron. This cross-hatched, geometric pattern forms when iron-nickel alloys cool extremely slowly.

Raimond Spekking, Wikimedia Commons

Raimond Spekking, Wikimedia Commons

Forging Technique

The preserved Widmanstatten pattern revealed critical information about how ancient metalworkers crafted the dagger. If heated above 950°C (1,742°F), this crystalline structure would have been destroyed and recrystallized into different forms. Since the pattern remained intact, researchers concluded the blade was manufactured using low-temperature heat forging techniques.

Lime Evidence

Chemical analysis of the dagger's golden hilt highlighted calcium deposits without sulfur, indicating the use of lime plaster as an adhesive for decorative elements. This detail proved important because ancient Egyptians during Tutankhamun's time primarily used organic glues or gypsum plaster (calcium sulfate) for goldwork.

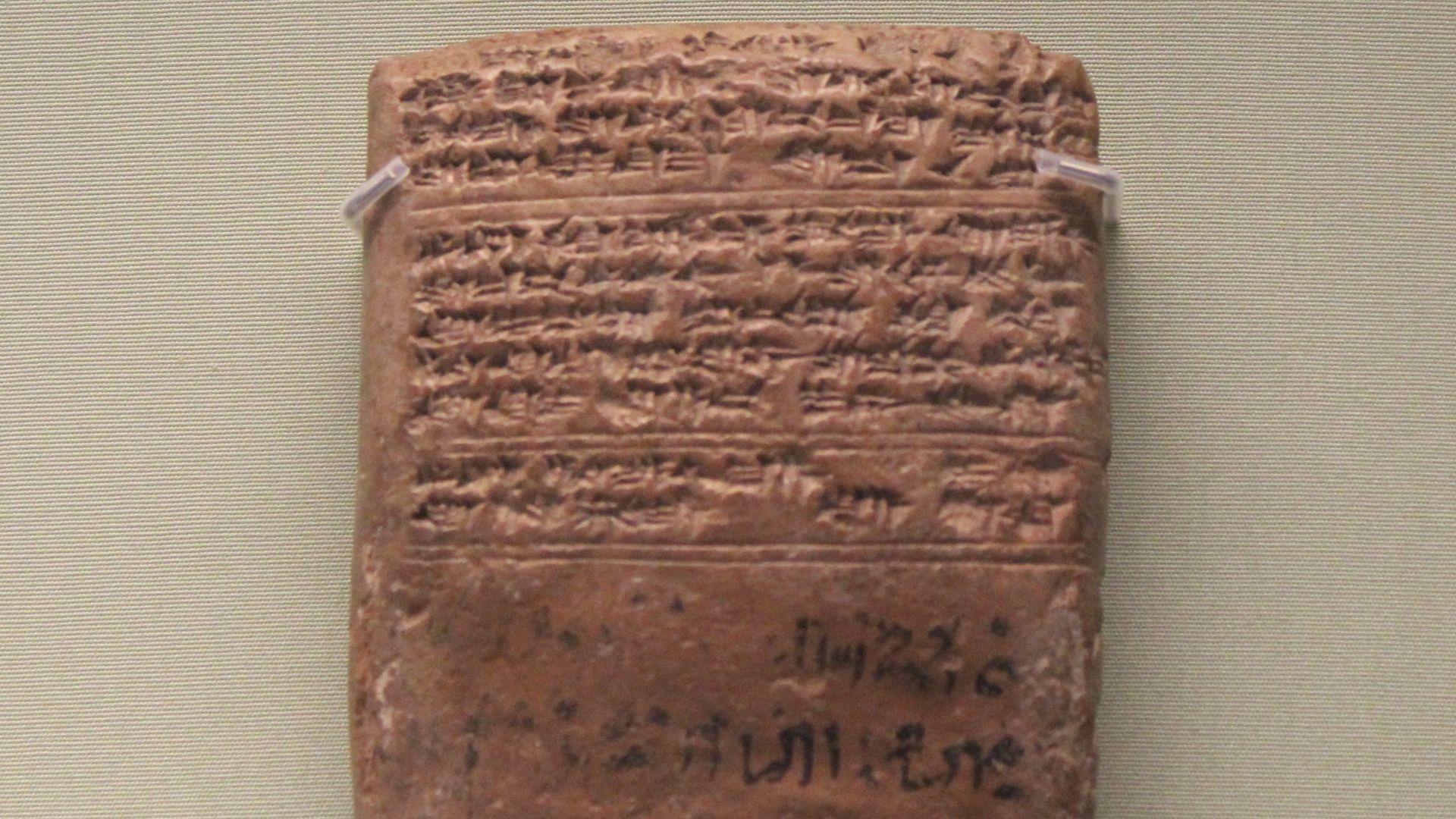

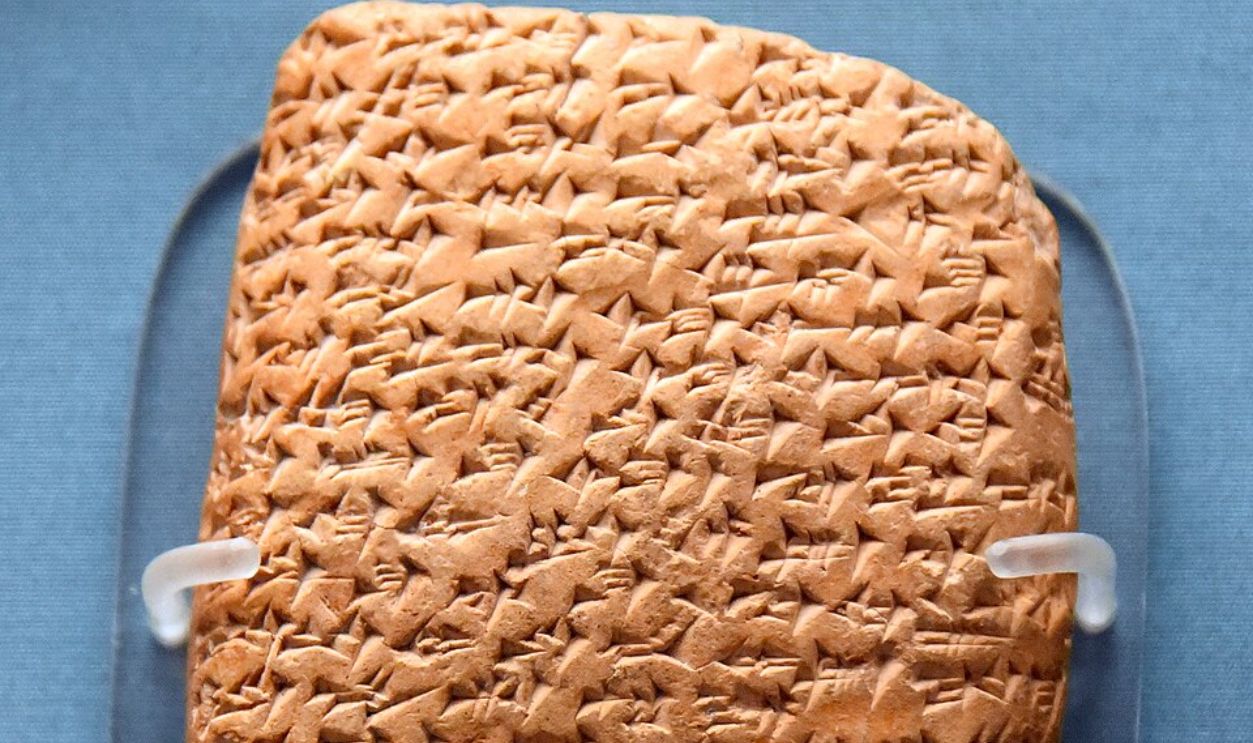

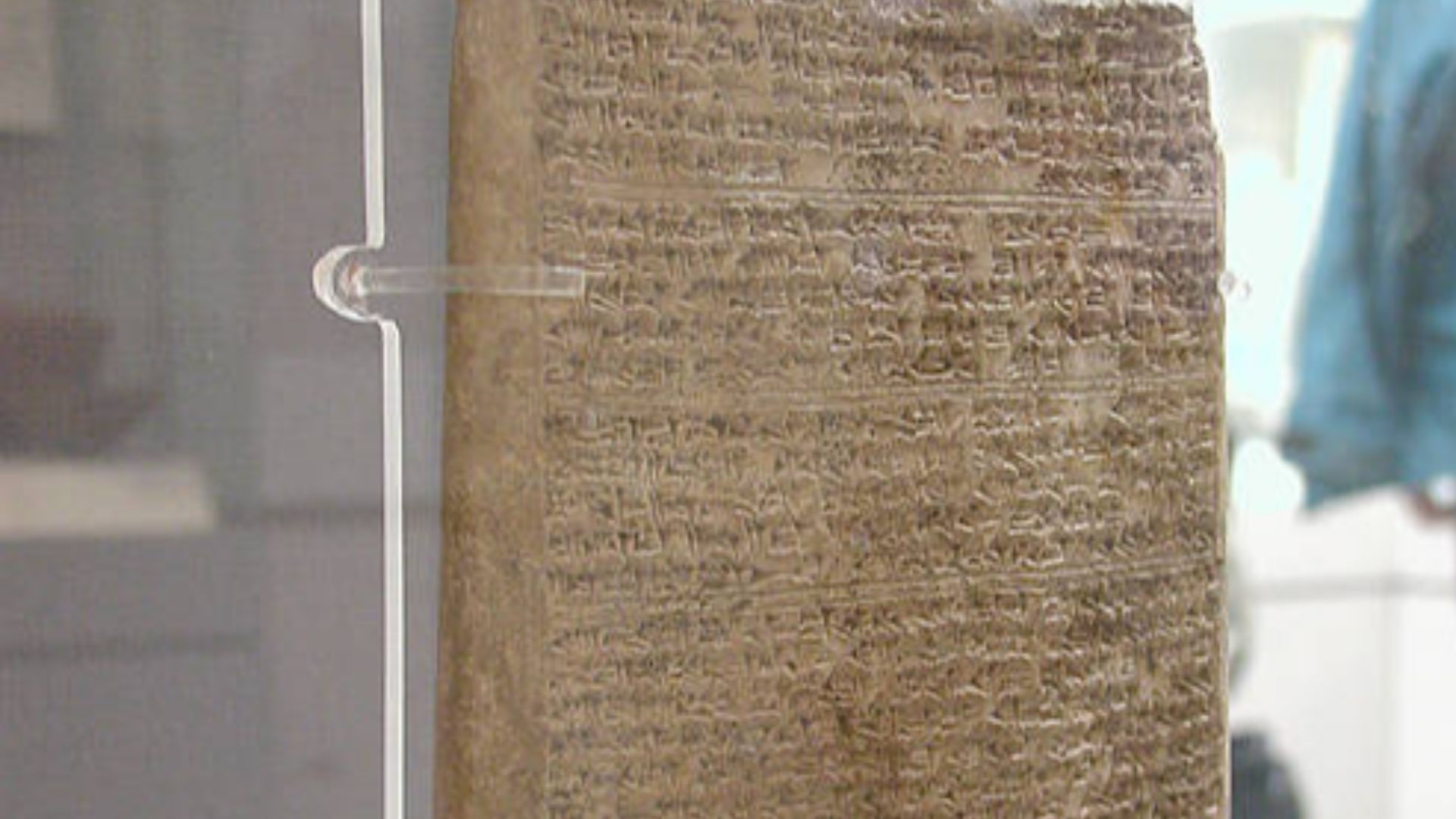

Amarna Letters

The breakthrough came from ancient clay tablets, not modern laboratories. The Amarna Letters document international relations during Egypt's 18th Dynasty. These 3,400-year-old tablets, considered among humanity's oldest diplomatic archives, contain over 350 letters between Egyptian pharaohs and neighboring rulers.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

EA 22 And EA 23

Two specific letters (designated EA 22 and EA 23) from Tushratta, King of Mitanni, to Pharaoh Amenhotep III describe royal gifts that included iron daggers with gold hilts, golden sheaths, and precious stone inlays. The descriptions tantalizingly match objects found in Tutankhamun's tomb.

Mitanni Connection

Besides, one Amarna letter mentions "1 dagger, the blade of which is of iron, its guard, of gold, with designs" sent when Amenhotep III married Mitanni princess Taduhepa. The Mitanni Empire, located in what's now southeastern Turkey and northern Syria, had mastered meteoritic iron working by 1500 BC.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Family Heirloom

Tutankhamun never witnessed the dagger's creation or presentation to his grandfather decades earlier. The blade passed through generations, possibly through Akhenaten, likely Tut's father. Royal treasuries preserved such extraordinary objects with diplomatic significance. When the young pharaoh died unexpectedly, priests selected this cosmic blade for burial, placing it against his mummified thigh.

Legacy Today

The meteorite dagger currently resides at the Grand Egyptian Museum. Visitors worldwide queue to glimpse this blade bridging Earth and cosmos, ancient craftsmanship and modern science. It demonstrates Bronze Age metallurgical sophistication and proves humans worked with extraterrestrial materials millennia ago.

Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons

Holger Uwe Schmitt, Wikimedia Commons