Mysteries Beneath The Sand

Some chapters of human history feel unfinished. Cities appear without warning, systems work without obvious blueprints, and cultures disappear before anyone writes things down, forcing researchers to read stories carved into silence.

Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) Civilization

Picture ancient Peru around 3000 BCE. While Egyptians were just beginning to stack stones into pyramids, a mysterious civilization was building massive stepped pyramids along Peru's arid coast. The Norte Chico people crafted one of the world's oldest urban centers, predating the Olmec by nearly two millennia.

Petty Officer 3rd Class Daniel Barker, Wikimedia Commons

Petty Officer 3rd Class Daniel Barker, Wikimedia Commons

Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) Civilization (Cont.)

Yet they did something utterly baffling: they had no pottery, no ceramics, and no visual art whatsoever. What makes archaeologists scratch their heads is the complete absence of weapons or defensive walls. These people sustained themselves almost entirely on fish and shellfish, growing only cotton to weave fishing nets.

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

Norte Chico (Caral-Supe) Civilization (Cont.)

It is said that they had no written language, no warfare, and around 1800 BCE, these folks simply dissolved into history. At Caral, six massive pyramids stand as silent witnesses to a civilization that defied every conventional rule of urban development.

Paulo JC Nogueira, Wikimedia Commons

Paulo JC Nogueira, Wikimedia Commons

Vinca Culture

The Danube River villages of southeastern Europe witnessed something extraordinary between 5500–4500 BCE: Europe's most sophisticated Neolithic society was flourishing with advanced metallurgy and mysterious symbols that might represent the continent's first writing system.

Andrej Dankovic, Wikimedia Commons

Andrej Dankovic, Wikimedia Commons

Vinca Culture (Cont.)

Three stone tablets discovered at Tartaria in 1961 bear several distinct characters that remain completely undeciphered, predating Sumerian cuneiform by centuries. Their clay figurines reveal women wearing modern-looking clothing: narrow skirts, sleeveless tops, hip belts, and intricate jewelry.

Vinca Culture (Cont.)

The Vinca people built Europe's largest prehistoric settlement and pioneered copper working a millennium before their neighbors. Despite all this, they vanished around 4500 BCE without leaving explanations of their language, beliefs, or sudden disappearance. This makes them one of archaeology's most frustrating enigmas.

Jan Janssonius, Wikimedia Commons

Jan Janssonius, Wikimedia Commons

Dilmun Civilization

Bahrain's environment tells an ancient story through 11,774 burial mounds covering five percent of the island. This is one of the world's largest prehistoric cemeteries from a civilization most people have never heard of. Dilmun controlled the copper trade routes of the Persian Gulf for millennia.

Rapid Travel Chai, Wikimedia Commons

Rapid Travel Chai, Wikimedia Commons

Dilmun Civilization (Cont.)

They monopolized the precious metal's journey from Oman's mines to Mesopotamia's cities around 3000 BCE. Ancient Sumerians wrote poetry about Dilmun as a paradise where death didn't exist, and the waters were always sweet. Archaeological evidence proves Dilmun was real.

© Think Heritage Author: Melanie Munzner, Wikimedia Commons

© Think Heritage Author: Melanie Munzner, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Konar Sandal

Around 2200 BCE in southeastern Iran's scorching desert, a sophisticated civilization built monumental structures and engaged in long-distance trade. It then disappeared so completely that most people have never heard of it. Konar Sandal holds secrets to a lost Bronze Age culture contemporary with Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley.

Konar Sandal (Cont.)

Proof of advanced metallurgy, elaborate architecture, and extensive trade networks reaching across ancient Persia has been uncovered. The site shows a society that created distinctive pottery and worked with precious materials, suggesting significant wealth and cultural development. However, we know almost nothing about their language, political structure, or daily life.

Mhsheikholeslami, Wikimedia Commons

Mhsheikholeslami, Wikimedia Commons

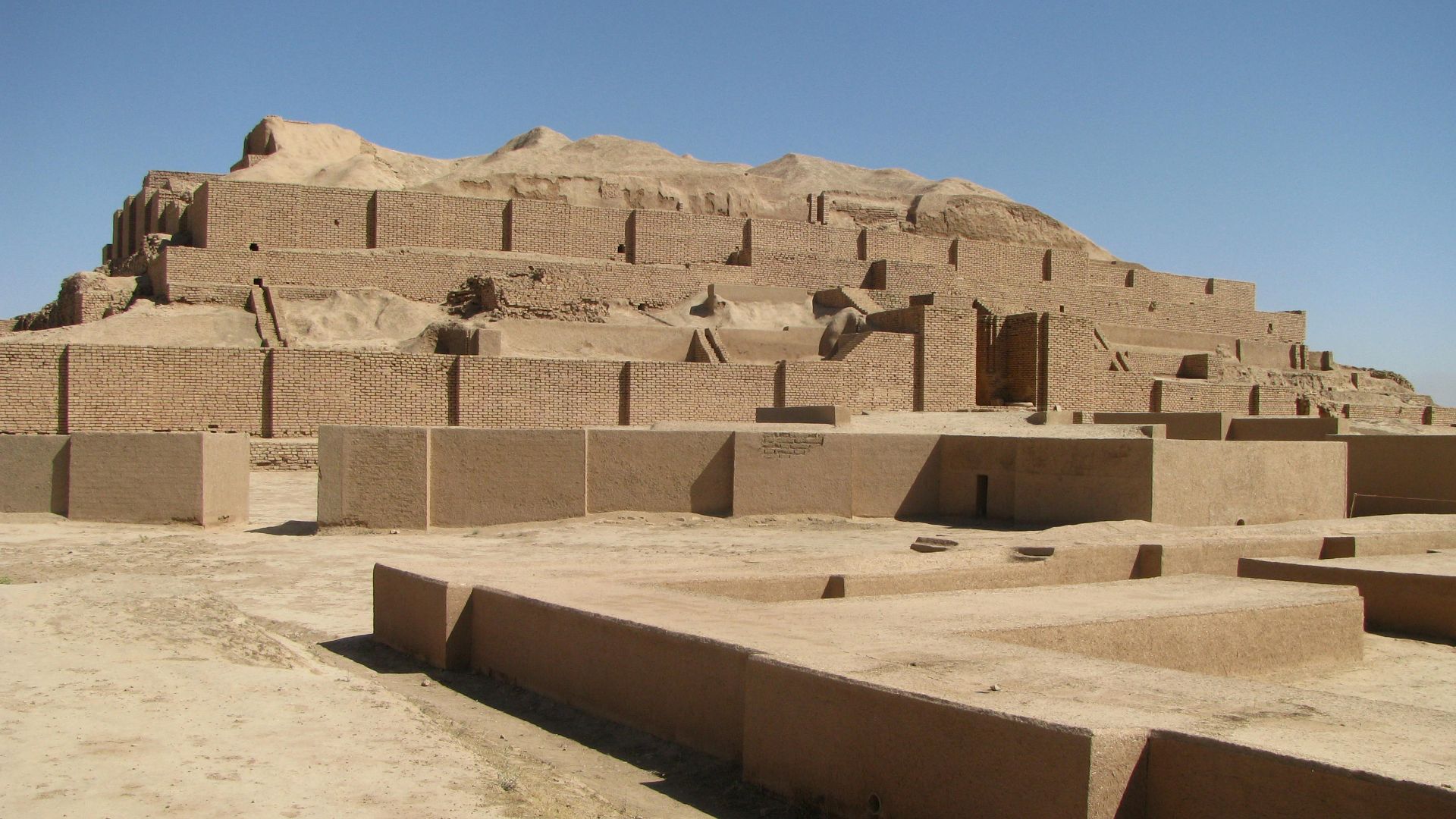

Elam

Southwest Iran's ancient power spoke a language so unique that it has no known relatives anywhere on Earth. This complete linguistic isolate baffled scholars until 2022, when researchers finally cracked their Linear Elamite script after millennia of silence.

Kaviani flag, Wikimedia Commons

Kaviani flag, Wikimedia Commons

Elam (Cont.)

Elam flourished from 3200 BCE to 539 BCE, building ziggurats, creating exquisite metalwork, and frequently warring with their Mesopotamian neighbors. The Elamites built Susa, one of humanity's oldest cities, around 4000 BCE and developed writing systems nearly as early as the Sumerians.

Mehdi Zali.K, Wikimedia Commons

Mehdi Zali.K, Wikimedia Commons

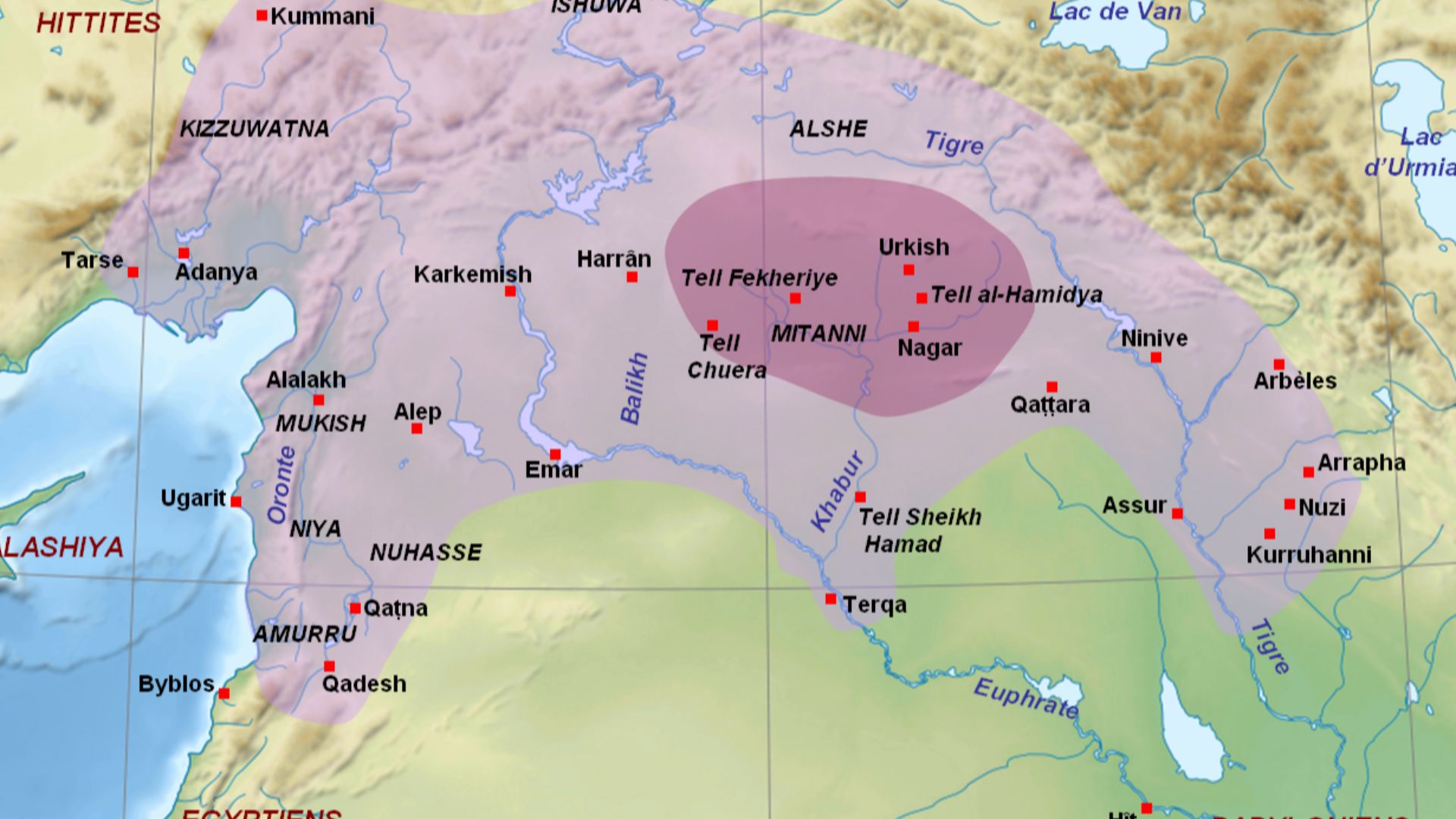

Kingdom Of Mitanni

For roughly 150 years during the Late Bronze Age, the Kingdom of Mitanni stood among the ancient world's superpowers—part of an exclusive "Great Power Club" alongside Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia, and the Hittites. Yet today, this once-mighty empire has been reduced to hardly more than a name.

Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Semhur derivative work: Zunkir (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Near_East_topographic_map-blank.svg: Semhur derivative work: Zunkir (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Kingdom Of Mitanni (Cont.)

The Mitanni's capital city, Washukanni, was mentioned repeatedly in Egyptian, Hittite, and Assyrian texts between 1500–1300 BCE, yet archaeologists still haven't definitively located it. We know Mitanni princesses married Egyptian pharaohs—one possibly becoming the famous Nefertiti—and their master horse trainers revolutionized chariot warfare across the Near East.

Sebastian Hageneuer, Wikimedia Commons

Sebastian Hageneuer, Wikimedia Commons

Kerma Culture

Swiss archaeologist Charles Bonnet spent decades excavating southern Nile sites before finding evidence of a Nubian civilization so powerful it invaded Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period and established diplomatic relations with the occupying Hyksos.

Matthias Gehricke, Wikimedia Commons

Matthias Gehricke, Wikimedia Commons

Kerma Culture (Cont.)

The Kingdom of Kerma (2500–1500 BCE) rivaled ancient Egypt at its zenith. Archaeologists discovered massive royal tumuli containing hundreds of human sacrifices and enormous wealth, which served as clear indicators of a sophisticated state. The Kermans built unique circular African structures.

Kerma Culture (Cont.)

These were defended by walls with no known prototypes anywhere in the Nile Valley. Their distinctive black-topped red pottery, created without wheels, remains among the Nile's most beautiful ceramics. Egyptian conquest around 1500 BCE increasingly "Egyptianized" Kerma.

Matthias Gehricke, Wikimedia Commons

Matthias Gehricke, Wikimedia Commons

Land Of Punt

Ancient Egyptians organized elaborate trading expeditions to a fabled land called Punt, returning with gold, myrrh, frankincense, exotic animals, and tales of wonder. After thousands of years, scholars still can't agree where Punt actually was.

Land Of Punt (Cont.)

Temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahri beautifully depict Queen Hatshepsut's famous expedition around 1470 BCE, showing beehive houses, giraffes, and treasures, but geographical clues remain frustratingly vague. Punt appears in Egyptian records spanning over a millennium as the source of luxury goods and the "God's Land" blessed with divine favor.

Ismoon (talk) 22:02, 2 March 2020 (UTC), Wikimedia Commons

Ismoon (talk) 22:02, 2 March 2020 (UTC), Wikimedia Commons

Tuwana Kingdom

Rising from the Hittite Empire's ashes around the 9th century BCE, the Kingdom of Tuwana became central Anatolia's important bridge between East and West—facilitating trade, diplomatic missions, and possibly even bringing the Phoenician alphabet to Greece.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Tuwana Kingdom (Cont.)

Despite this pivotal role,c was largely erased from history when conquering empires rewrote the records to glorify themselves. The kingdom controlled the strategic Cilician Gates through the Taurus Mountains, the vital passageway connecting Europe and Asia.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Nok Civilization

West Africa's oldest known civilization emerged around 1000 BCE in modern Nigeria, mastering iron smelting and creating some of sub-Saharan Africa's most extraordinary terracotta sculptures. The name "Nok" simply comes from the village where a tin miner accidentally discovered the first sculpture in 1928.

Nok Civilization (Cont.)

Their distinctive artwork depicts humans and animals in intricate, unique styles that influenced subsequent African societies for centuries. Archaeological evidence indicates the Nok developed advanced agricultural productivity through iron tools, implying complex social organization and stable governance. Settlements were well-organized, suggesting an established economy.

Marie-Lan Nguyen, Wikimedia Commons

Marie-Lan Nguyen, Wikimedia Commons

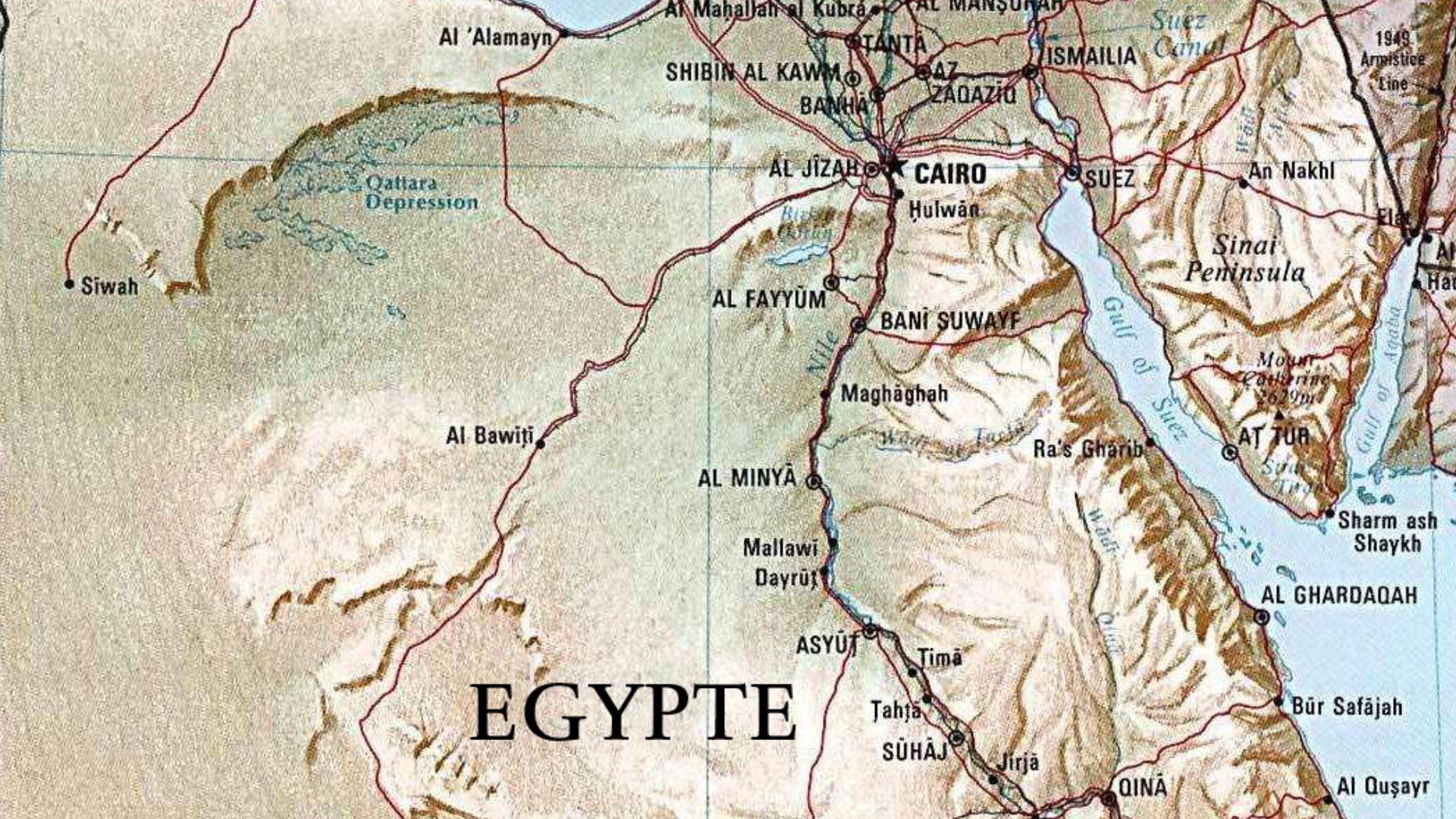

Nabta Playa

Six thousand years before Christ, when the Sahara Desert was a verdant savannah with seasonal lakes, an advanced African civilization built stone circles resembling Stonehenge in what is now Egypt's barren Nubian Desert. Nabta Playa's inhabitants constructed megalithic astronomical alignments to track summer solstices.

Nabta Playa (Cont.)

Rock paintings show cattle grazing in areas that have been a lifeless desert for millennia, proof of dramatic environmental changes that ultimately doomed this civilization. These weren't simple nomads but people who farmed, domesticated animals, and fashioned ceramic vessels over 9,000 years ago.

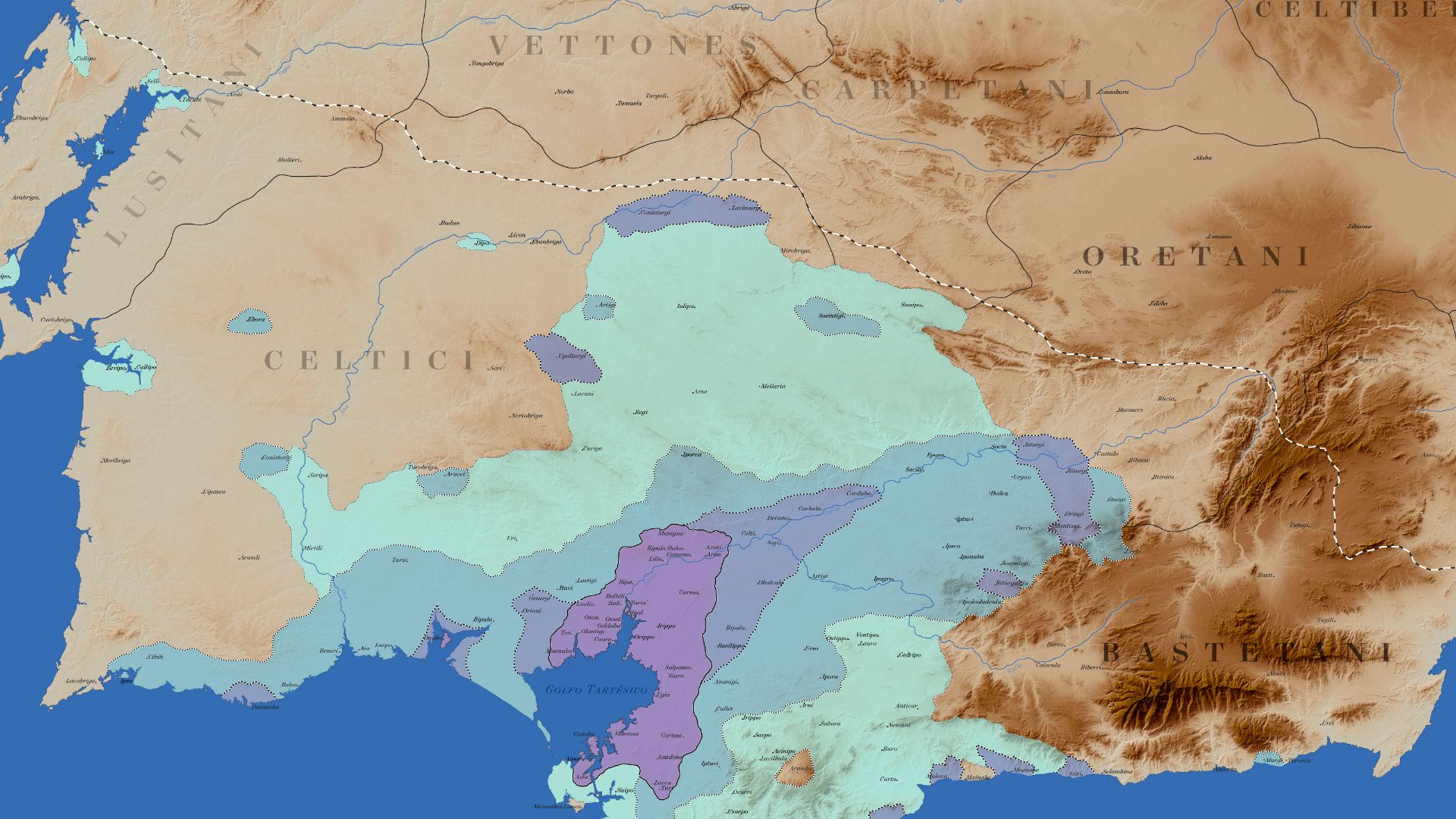

Tartessos

Imagine a thriving Bronze Age civilization performing a bizarre ritual: feasting in grand halls, sacrificing horses and cattle to appease unknown gods, then deliberately setting their temple ablaze and burying it under 14 feet of earth before vanishing without a trace.

Axel Coton Gutierrez, Wikimedia Commons

Axel Coton Gutierrez, Wikimedia Commons

Tartessos (Cont.)

This actually happened around 500 BCE when Tartessos, southwestern Spain's wealthy trading culture, mysteriously disappeared after flourishing for four centuries. Ancient Greeks and Romans wrote about Tartessos as a legendary land of silver, copper, and lead.

Sogdiana

Situated between mountain ranges in Central Asia, Sogdiana occupied the critical crossroads of the ancient Silk Road for over two millennia. However, most people have never heard of these master merchants who facilitated trade between China, India, Persia, and the Mediterranean.

DEMIS Mapserver, Pataliputra, Wikimedia Commons

DEMIS Mapserver, Pataliputra, Wikimedia Commons

Sogdiana (Cont.)

The Sogdians spoke an Eastern Iranian language closely related to Bactrian and created a trading network that dominated East-West commerce from the 4th to 8th centuries CE. Alexander the Great needed a genocidal campaign and multiple town foundations to conquer Sogdiana in 329–327 BCE.

A.Davey from Portland, Oregon, EE UU, Wikimedia Commons

A.Davey from Portland, Oregon, EE UU, Wikimedia Commons

Bactria (BMAC)

Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan's river valleys nurtured the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex between 2200 and 1700 BCE. This Bronze Age civilization was so advanced and wealthy that it's been called the "Oxus civilization”. Bactria developed big oasis communities with irrigation systems, trading lapis lazuli, bronze, and other valuables across vast distances.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Bactria (Cont.)

The region's natural defenses—Pamir Mountains to the north, Hindu Kush to the south—created a protected zone where proto-urban civilization flourished during the 2nd millennium BCE. Ancient Zoroastrian texts called it "beautiful Bactria, crowned with flags" and listed it among the sixteen perfect lands created by Ahura Mazda.

Silla Kingdom

One of the longest-standing royal dynasties ever, lasting from 57 BCE to 935 CE, ruled most of the Korean Peninsula, yet left remarkably few burials and archaeological traces for researchers to study. The Silla Kingdom's founder was allegedly hatched from a mysterious egg found in the forest.

Silla Kingdom (Cont.)

He then married a queen born from a dragon's ribs, according to legends that blur history with mythology. Only scattered intact remains help archaeologists piece together Silla culture, like a woman discovered in 2013 near the historic capital Gyeongju whose bones revealed she was likely a vegetarian.

by martinroell, Wikimedia Commons

by martinroell, Wikimedia Commons

Catalhoyuk

Around 7500 BCE in modern Turkey, roughly 8,000 people lived in the world's largest Neolithic settlement. Talk about a bizarre honeycomb city with no streets whatsoever. Catalhoyuk's inhabitants accessed their homes by climbing ladders through roof openings and traversing rooftops like an ancient parkour course.

Murat Ozsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Murat Ozsoy 1958, Wikimedia Commons

Catalhoyuk (Cont.)

This architectural oddity raises fascinating questions about social organization and defense strategies in one of humanity's earliest urban experiments. Houses were built directly against each other, creating continuous walls that may have served defensive purposes without traditional fortifications. Interior walls featured elaborate murals depicting bulls, vultures, and hunting scenes.

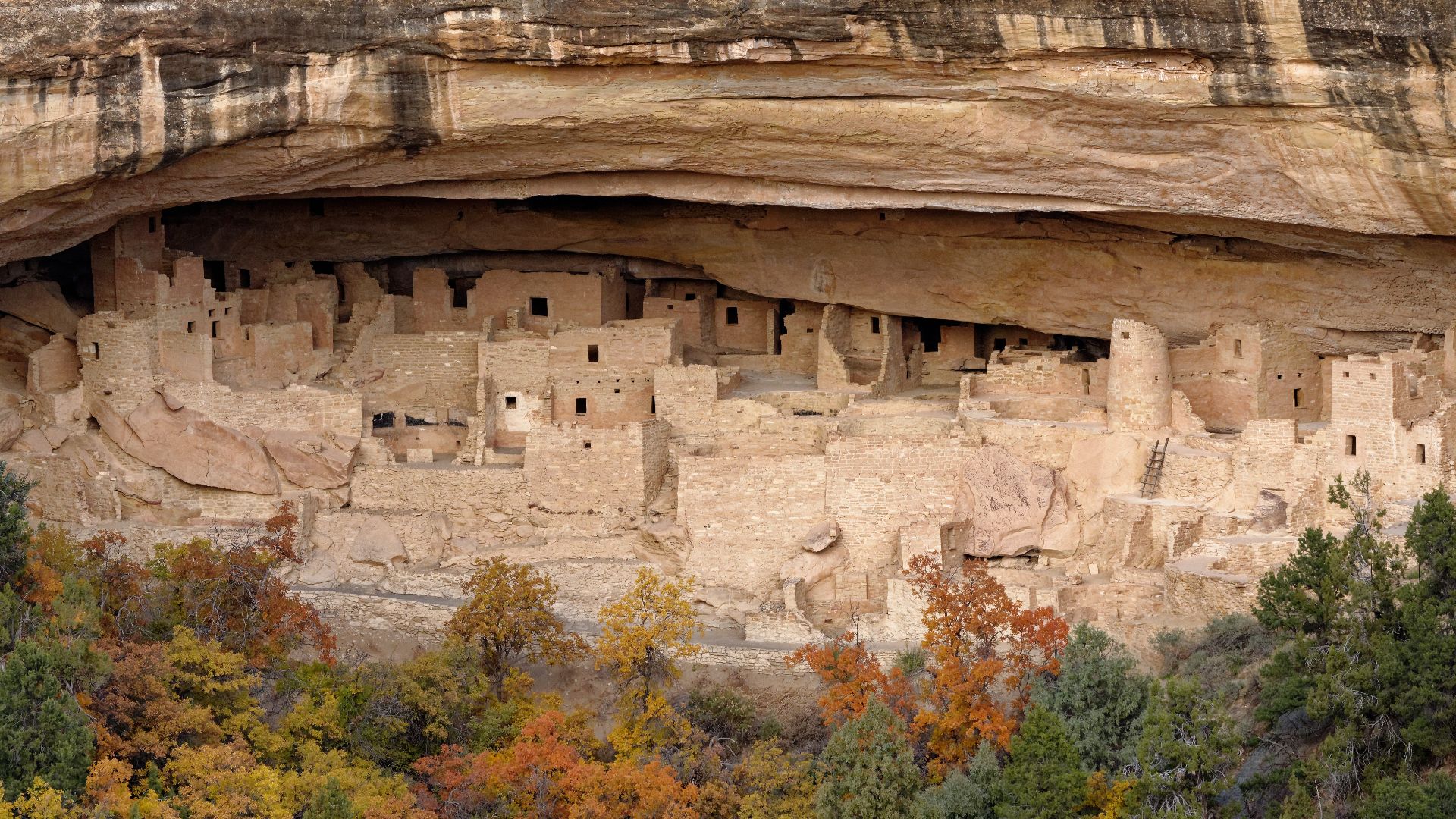

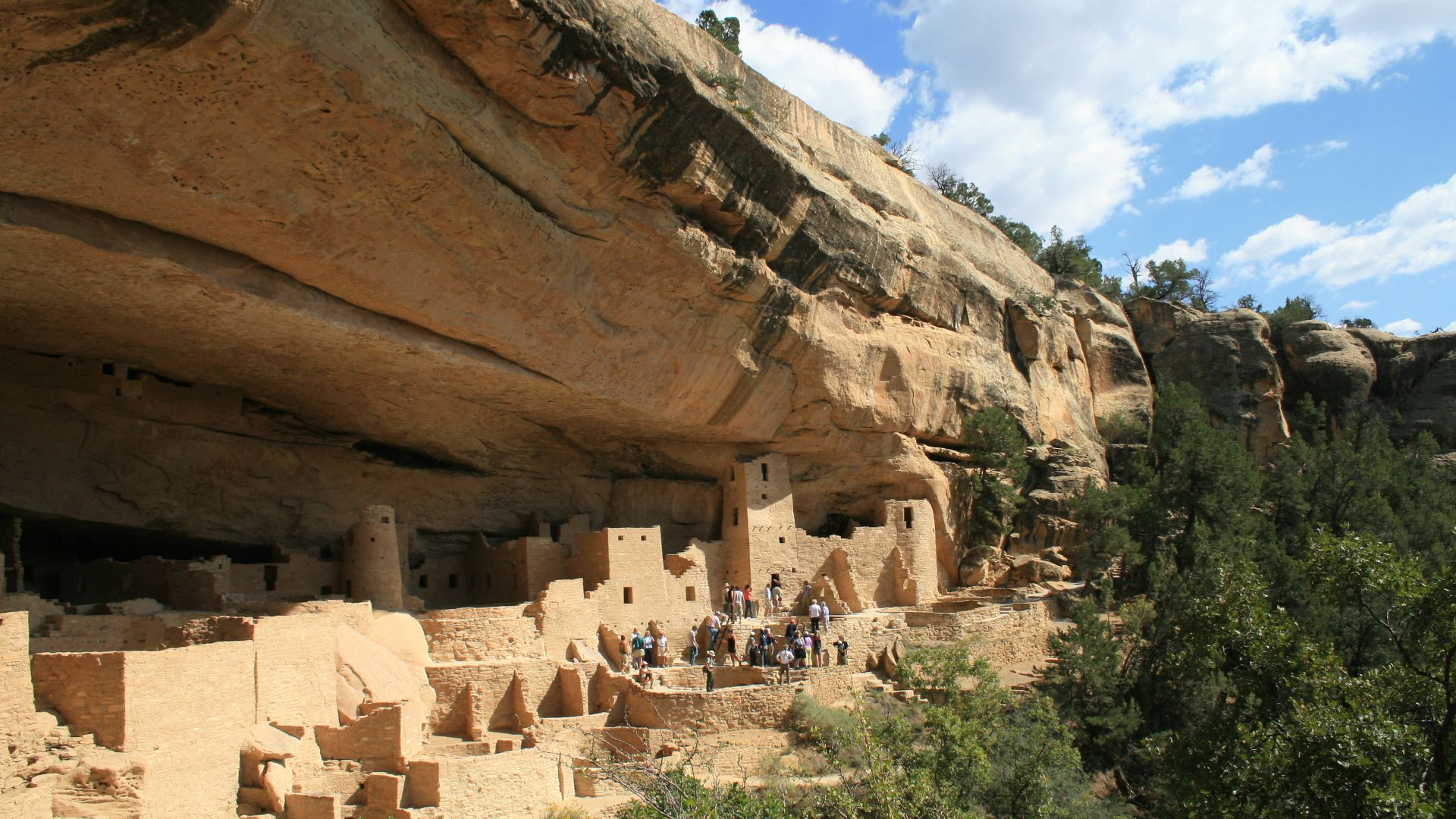

Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi)

Carved directly into sheer cliff faces across Utah, Arizona, New Mexico, and Colorado stand magnificent pueblo cities that their builders mysteriously abandoned by the end of the 13th century. The Ancestral Puebloans, called "Anasazi" (meaning "ancient enemies" in Navajo), constructed architectural marvels like Mesa Verde's Cliff Palace.

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

Ancestral Puebloans (Cont.)

By 1300 CE, they'd abandoned these magnificent cities, migrating southward to establish pueblos in New Mexico and Arizona, where their descendants still live today. Theories about their departure range from prolonged drought and famine to warfare, resource depletion, or even extraterrestrial intervention, according to fringe theorists.

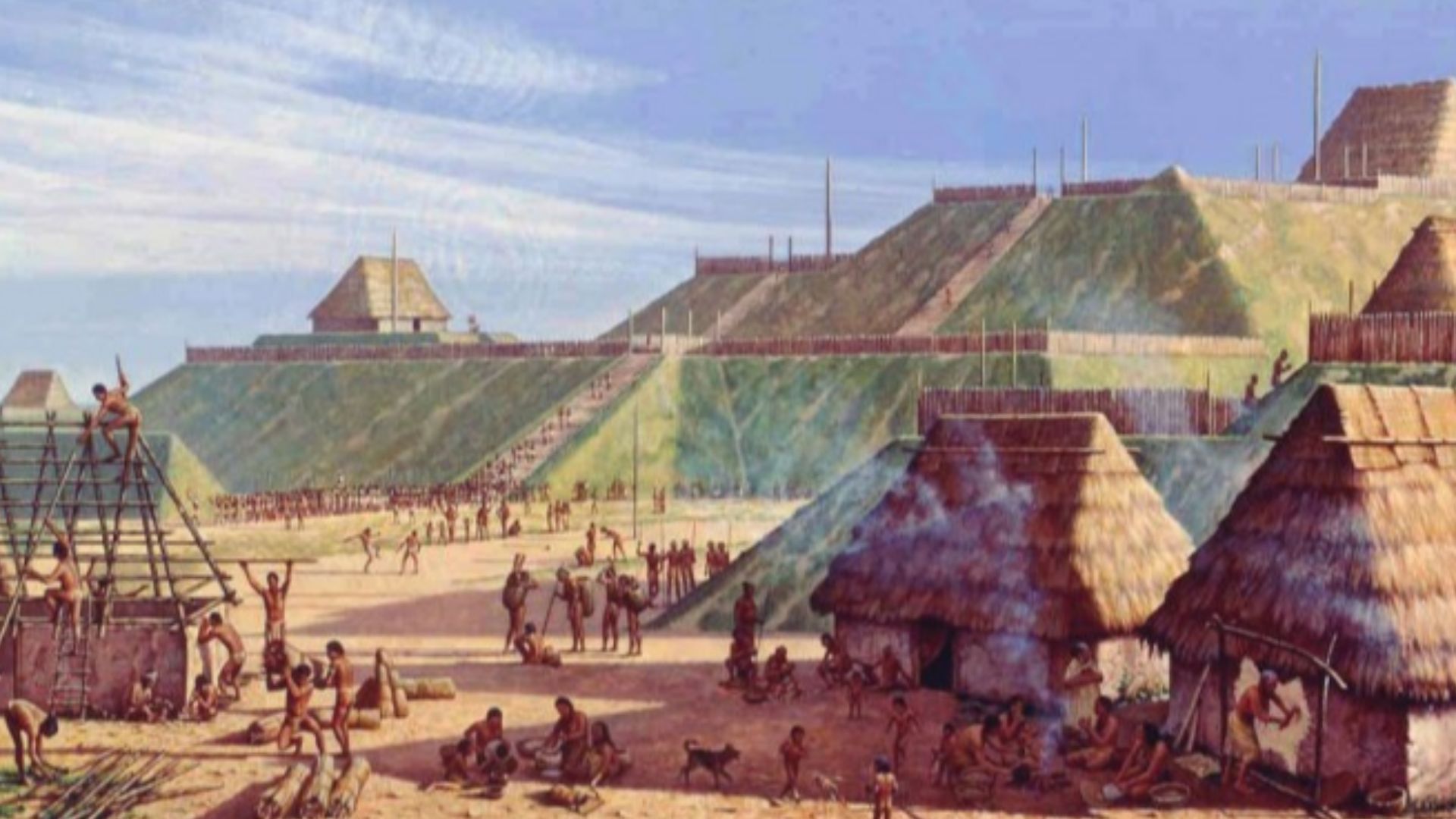

Mississippian Culture

Near modern St Louis, around 1050 CE, stood North America's largest pre-Columbian city—Cahokia. It was a sprawling metropolis of approximately 20,000 people featuring massive earthen pyramids, one over 100 feet tall, requiring 14 million baskets of dirt to construct.

Thank You (24 Millions ) views, Wikimedia Commons

Thank You (24 Millions ) views, Wikimedia Commons

Mississippian Culture (Cont.)

This was an urban center with 120 earthen mounds, extensive plazas, and a wooden "Woodhenge" structure for tracking astronomical events. The Mississippian culture turned the American Midwest into an interconnected civilization spanning from the Great Lakes to the Gulf Coast between 800 and 1600 CE.

Midnightblueowl at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Midnightblueowl at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Mississippian Culture (Cont.)

Cahokia's strategic position near the confluence of the Mississippi, Missouri, and Illinois rivers made it a critical trade hub where copper from the Great Lakes, shells from the Gulf, and exotic goods from across the continent changed hands. Then, around 1200 CE, massive flooding devastated the region.

Michael Hampshire for the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site., Wikimedia Commons

Michael Hampshire for the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site., Wikimedia Commons

Derinkuyu (Underground Cities)

Beneath Turkey's Cappadocia region lie underground cities descending five stories deep, housing up to 20,000 people plus livestock in complete subterranean darkness. Derinkuyu was discovered accidentally in 1963 when a local resident found a mysterious room behind his basement wall.

Ahmet KAYNARPUNAR, Wikimedia Commons

Ahmet KAYNARPUNAR, Wikimedia Commons

Derinkuyu (Cont.)

These were urban complexes featuring ventilation shafts, wells reaching deep aquifers, wine presses, chapels, storage rooms, and even schools—everything needed for extended underground habitation. Huge rolling stone doors weighing hundreds of pounds could seal entire levels from invaders. The cities reached their greatest development between 500 and 1000 CE.

Bjorn Christian Torrissen, Wikimedia Commons

Bjorn Christian Torrissen, Wikimedia Commons

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

Alexander the Great's conquest reached its easternmost limits in Bactria (modern Afghanistan-Uzbekistan border) around 330 BCE, establishing Greek colonies that evolved into an independent Hellenistic kingdom so fabulously wealthy it became known as the "empire of 1,000 cities”.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (Cont.)

The Greco-Bactrian kings controlled Silk Road passages, accumulating enormous wealth through trade between East and West while maintaining Greek language, philosophy, and artistic traditions thousands of miles from the Mediterranean. Archaeological discoveries at Ai Khanoum showed a Greek city complete with a gymnasium, a theater, and philosophical texts.

Rani nurmai, Wikimedia Commons

Rani nurmai, Wikimedia Commons