Ever wonder where the term "Black Mirror" comes from? Its origins are rooted in a surprising historical trend.

A Real Fake

When modernist painters experimented with abstract and non-representational art, the realism that dominated former epochs suddenly seemed quaint and old-fashioned. After all, why does a face or a tree need to look like a face or a tree on canvas? Why all this fidelity to verisimilitude when an artwork wasn’t the thing itself? Besides, the advent of photography made portraiture and landscape work redundant. Except, that is, for one thing.

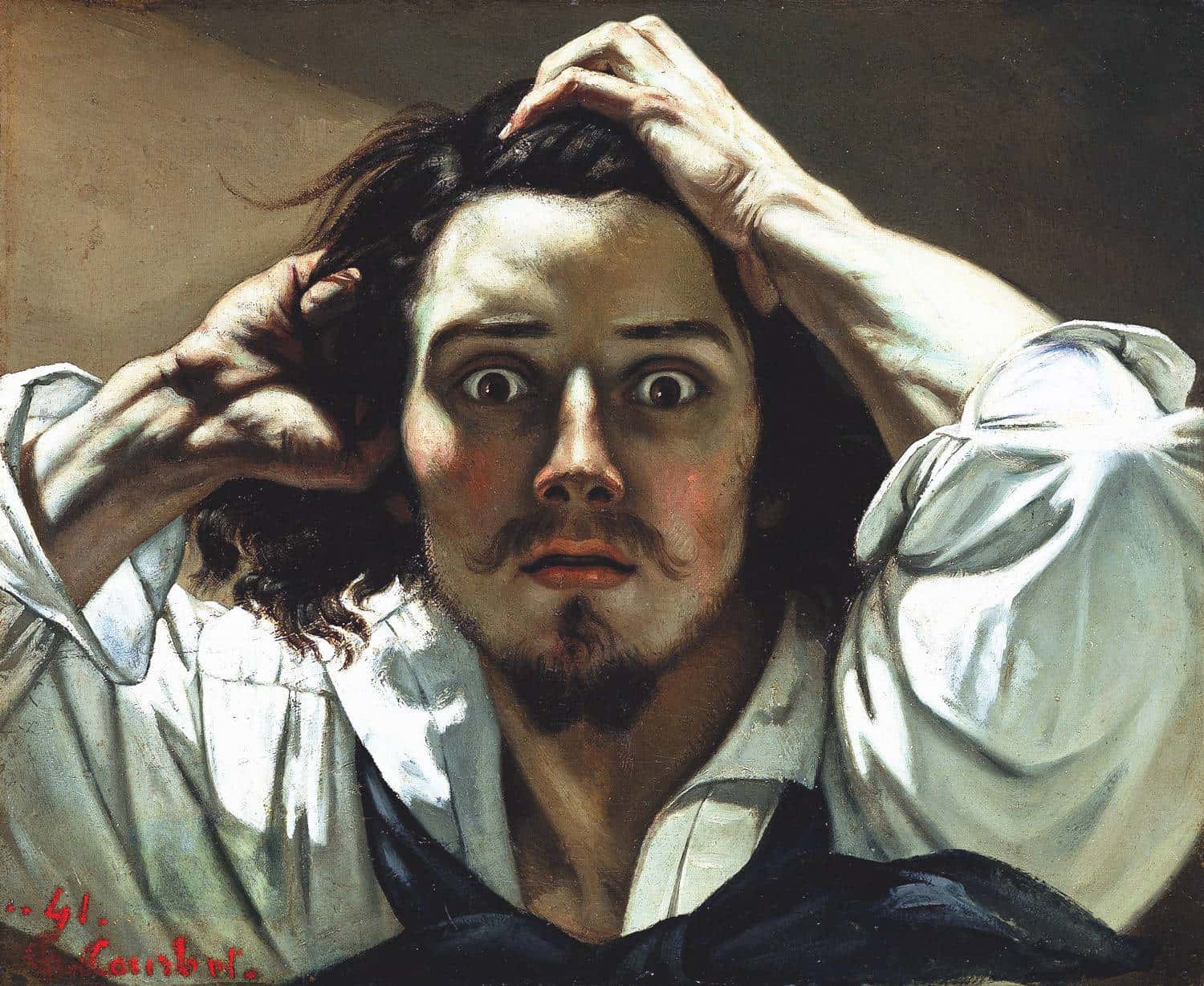

Even before terms like "cubism" arrived, artists were aware that realism wasn’t actually objective or scientific. Indeed, they were aware that realism merely depicted a subjective perspective of reality, just in its own way. 19th-century artist Gustave Courbet, for example, famously played with breaking the fourth wall in his otherwise realistic self-portraiture, pointing out the subjective perspective of the work as well as its status as artwork.

But when it comes to realistic landscapes, this subjective history is even more fascinating—thanks in part to the strange and now forgotten technological advancement called a “black mirror”.

Enter: The Black Mirror

Yes, that’s right, a “black mirror” isn’t just a dystopian television show on Netflix. Also called a “Claude glass” after the 17th-century painter Claude Lorrain, the device looks much like a large makeup compact. To use it, 18th-century painters would first turn their back on the landscape itself. They would then set up the black mirror to frame what they were going to paint. Some connoisseurs even recommended carrying two mirrors, "one to manage reflections of great and near objects and a flatter glass for distant and small objects”.

Besides letting them safely observe phenomena like sunsets, the mirror also simplified the color and tones of the landscape—supposedly to palettes reminiscent of Claude Lorrain’s own work, hence the secondary name. Although there’s no indication Lorrain used black mirrors himself, English artist William Gilpin stated the common theory of the time that "they give the object of nature a soft, mellow tinge like the colouring of that Master”.

Black mirrors were then a sort of proto camera lens, and using them to paint a landscape was like going off a stylized photograph to re-construct the living reality. Obviously, any sense of objective realism in landscape painting goes out the window when using a black mirror. Quite purposely so, too. No one who used them seemed to have much existential dread about what reality, exactly, they were depicting.

In fact, its acolytes were downright fanatical.

Through A Mirror Darkly

Although used to great effect in landscapes of the late 18th-century, black mirrors weren’t limited to artists. Tourists also loved to use the Claude mirror to more deeply appreciate the landscape as they looked around them. Think of it like when your road-trip companion tells you the roadside greenery looks so much better with their expensive, polarized sunglasses on. To many, black mirrors enhanced the perception of your surroundings. As such, the fanaticism for black mirrors went beyond depicting reality and into actually witnessing it.

Indeed, the poet Thomas Gray was such a proponent of receiving the beauty of nature via the black mirror that the device briefly became known as the “Gray mirror”. His travelogue Journal of his Tour in the Lake District discusses his experiments with the mirror in-depth. Hilariously—and tellingly—enough, one anecdote describes how Gray, too intent on his mirror instead of the ground beneath him, fell into “a dirty lane” and broke his hand. On the other hand, Gray did claim his mirror let him see "the sun set in all its glory".

Dim-Colored Glasses

Painters and travelers who made use of the Claude mirror didn’t seem to mind the veil they put between themselves and reality. However, other people certainly did. Another poet, Hugh Skye Davies, deplored that black mirror enthusiasts turned their backs on nature instead of confronting it. Stories like that of Thomas Gray’s distracted tumble certainly didn’t help matters.

Moreover, with the coming of the 19th century, further developments in the camera obscura—in use for centuries already— edged out the Claude mirror when it came to artistic endeavors. Not that this evolution fundamentally changed the artist’s relationship with reality. After all, the dark chamber of the camera obscura, which looks out into reality through a pinpoint, is a sibling of the black mirror’s reflective world.

Seeing Into The Future

Even today, the black mirror isn’t quite obsolete. In fact, you can still see them in action. In the Desert View Watchtower by the Grand Canyon, 20th-century architect Mary Colter installed some for observing the rocky landscape. Yet more generally, don't Instagram and other social media filters perform much the same function? With a variety color differences and shades, filters manipulate photographs to emphasize certain tones and create specialized atmosphere.

We still call that reality, even as we know it's distorted. Realism has always been and always will be an ever-changing perspective. Black mirrors just turn it into a physical phenomenon.