England's Most Mysterious Site

Stonehenge may be one of the most iconic sites in the world, boasting Unesco World Heritage Site status and gracing many a history buff’s bucket list—but the details of this ancient monument were shrouded in mystery for centuries. However, in 2013, scholars believed they discovered Stonehenge’s true purpose—and it’s absolutely bizarre.

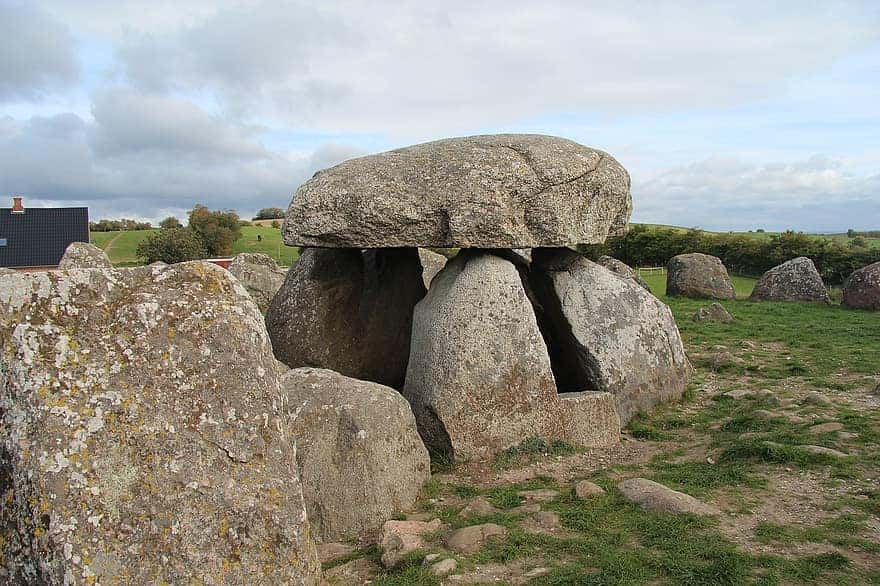

1. The Makeup

There are two main types of stone within Stonehenge: the large vertical stones and the stones that form the arches are sarsen stones, with an average sarsen weighing 25 tons. The smaller stones are bluestones, due to their bluish tint. The giant three-piece sarsen arches—the ones everyone thinks of when they think of Stonehenge—are called trilithons.

2. A 150-Mile Journey

Some of Stonehenge's “smaller” bluestones—which weigh up to four measly tons—have been linked to the Preseli Mountains in Wales. Modern scholars believe that these bad boys had to be transported 150 miles to become part of Stonehenge. How, you ask? Well, that remains one of Stonehenge’s great mysteries, with theories ranging from rafts, oxen, or ball-bearing technology to more outlandish possibilities like aliens and magic.

3. A Buried History

Stonehenge’s true purpose is still a mystery, but anthropologists confirmed that the site began as a place for prehistoric people to bury their cremated dead. These burials started around 5000 years ago, roughly 500 years before the famous stone circle was erected. The 56 pits—known as “Aubrey holes"—once housed the remains of at least 64 people from the Neolithic period.

But the stones have a whole other purpose of their own.

4. Reach For The Stars

In general, people think Stonehenge was built to align with the movements of the sun, but in exactly which way? Well, that question has kept astronomers busy for centuries. Here's one theory: In 1771, an astronomer named John Smith argued that, since there were around 30 sarsen stones, they represented the days of the typical month. He also claimed that if you multiplied the 30 stones by the 12 astrological signs, you'd get 360—close to the number of days in a year.

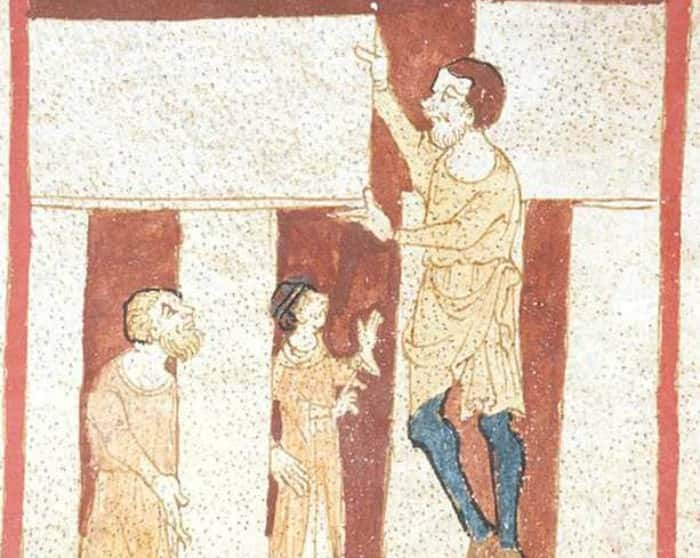

5. A Wizardly Aid

Well into the Middle Ages, people thought that Merlin the wizard moved the stones with the help of an army, a giant, and, of course, magic. Geoffrey of Monmouth started this theory. He was a cleric and "historian" whose mythical account of Medieval England included the legend of King Arthur.

6. You Get The Picture

The very first known image of Stonehenge depicts Monmouth's version of events. It shows Merlin constructing Stonehenge with the help of his giant buddy. The image is in a valuable manuscript that dates all the way back to the early 14th century.

Wikimedia Commons

Wikimedia Commons

7. Write About Now

The first written record of Stonehenge occurred in the 12th century. Back then, the monument went by "Stanenges" in an archaeological study by the explorer Henry of Huntingdon. The passage confirms that even back in 1130, people didn't know where Stonehenge came from. Huntingdon writes that the stones look like "doorways" but no one knows "how such great stones have been so raised aloft, or why they were built there.”

Over the next few centuries, "Stanenges" became "Stanhenge," "Stonhenge," "Stonheng" and "the stone hengles" until someone came to their senses in 1610. That's when the monument finally became known as “Stonehenge”.

8. Always A Popular Spot

While the stones were first erected around 2500 BC, we know that people had lived at the site long before. Archaeologists excavated a man’s skeleton in 1864 and radiocarbon dating shows that he died around 3,360 BC!

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

9. Noah Would Be Proud

The first ever guidebook for Stonehenge, written by Henry Browne and published in 1823, had a blatantly Biblical slant. The book claimed that Stonehenge was one of the few ancient structures that survived the Old Testament flood.

10. Full of Foam

In Virginia, there’s an odd replica of Stonehenge made out of styrofoam. Originally made as an April Fool's Day joke, people loved it so much that the structure became permanent. Its name? “Foamhenge” of course.

11. A Barrow of Laughs

The area around Stonehenge contains over 300 Bronze Age burial mounds known as barrows. However, their inhabitants didn't rest easily. Before the 20th century, treasure hunters and investigators opened these burials and removed their contents. Even with this dodgy track record, people still want to be buried near Stonehenge. In 2015, a local farmer built the first modern barrow. It had private niches in the rock so people could store cremation urns. The idea was very popular, too—the space was fully booked within 18 months.

12. Did You Keep The Receipt?

The last private owner of Stonehenge was an Englishman named Sir Cecil Chubb. He bought the site "on a whim" in 1915 for approximately $10,000 as a gift to his wife. She wasn’t all that happy with it, apparently, so he gave to the public instead. Chubb landed himself a knighthood for his kind gesture.

13. For The People

When Cecil Chubb gave Stonehenge to the public in 1915, he stipulated that the people should never have to pay "a sum exceeding one shilling" per visit. Alas, this kind gesture didn’t stick. These days admission will cost you £21.50 if you’re an adult.

14. Copycat Across The Pond

There is a full-sized (well, almost) replica of Stonehenge located in Texas, appropriately named "Stonehenge II." Built in modern times as an homage to the original, it’s about two thirds of Stonehenge's size and is made from steel and concrete.

15. Quit Badgering

Ol’ Gandalf the Grey said it best: “Even the smallest creature can change the course of history.” Right next door to Stonehenge—well, about 5 miles from it—a Bronze Age burial site was discovered by an unlikely archaeologist: a badger.

16. The Way Things Weren’t

The Stonehenge we see today is not necessarily a true reconstruction of the way it looked back in the day. Extensive restoration between 1901-1964 made it impossible to know exactly how the stones originally stood. One archaeologist described the monument as "a product of the 20th century heritage industry."

17. Start Your Engines

A strange replica of Stonehenge is located near Alliance, Nebraska. It's made entirely out of old spray-painted vintage cars and is called “Carhenge,” because of course it is.

18. Chip On Your Shoulder

Bizarrely, chisels used to be handed out to people visiting Stonehenge, so they could climb all over the monument, chip away at the ancient stones, and get their own souvenirs to take home. It wasn’t until 1977 that the authorities officially banned, you know, destroying a major monument.

19. What Lies Beneath

Stonehenge may appear to be all alone, but it wasn’t always that way. Not by a long shot. According to a recent survey of the grounds, the monument was once surrounded by chapels, ritual pits and burial mounds that formed a complex spatial relationship with Stonehenge. Radar, laser scanners and other advanced technologies detected the ancient structures hidden beneath the ground, much of it predating Stonehenge by centuries.

20. Henge Your Bets

The word “henge” comes from Stonehenge, but Stonehenge isn’t actually a true henge at all. A henge is defined as having a ring-shaped ditch and bank, with the ditch on the inside. Stonehenge’s ditch runs along the outside.

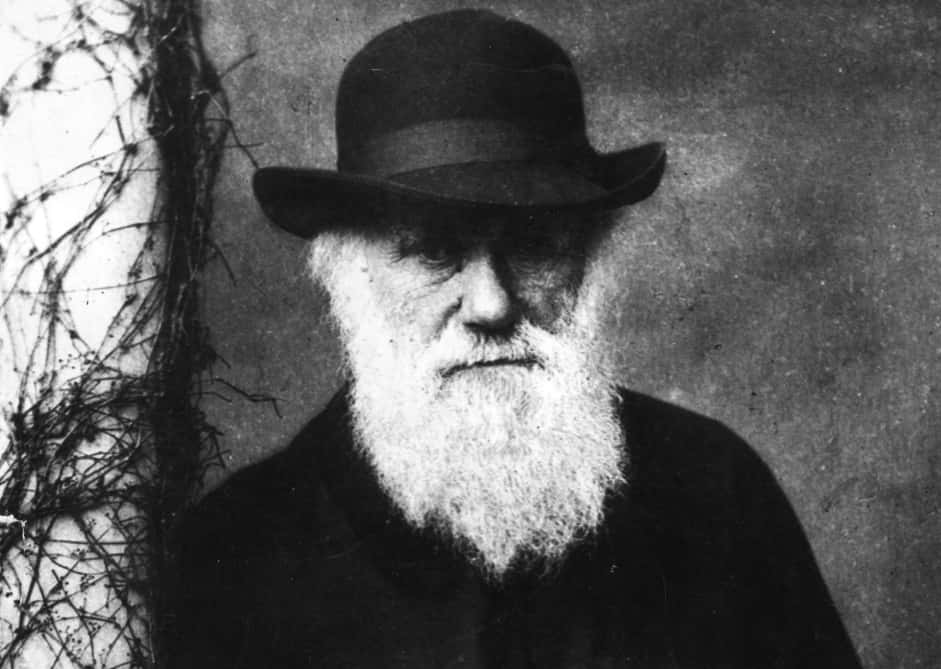

21. Darwin’s Discovery

Upon carrying out some of the first scientifically recorded excavations at Stonehenge in 1877, none other than Charles Darwin made a strange discovery. He concluded that one of the ancient stones had sunk into the soil and toppled over—all because of earthworms! They had churned through the soil so much that it became an unstable foundation.

22. Rings a Bell

In 2013, scholars suggested that Stonehenge's true purpose lay in the stone's unique acoustic properties. The study found that many of the stones issued metallic sound like that of a bell or a gong. A Presli village even used the bluestones as a church bell through the 18th century.

23. Party Hard

The Stonehenge Free Festival ran every year from 1971 to 1985, when thousands of 'New Age' followers would travel to Stonehenge to take drugs and party hard. A High Court injunction obtained by the authorities led to a violent clash at the 1985 festival, known as the "Battle of the Beanfield." Around 600 people were arrested.

24. This Round’s On Me

In 1923, archaeologist William Hawley discovered a bottle of port underneath a fallen sarsen stone near Stonehenge’s entrance. The bottle had been left there by antiquarian William Cunnington in 1802 for future excavators to enjoy. Sadly, the cork had decayed and almost all of the bottle’s contents were gone, but it’s the thought that counts. Here’s to you, Bill!

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23