He Was The Great Betrayer

The name “Marcus Junius Brutus” has become synonymous with the word “betrayal”. Brutus rose to power in Ancient Rome under the wing of Julius Caesar—then he plunged a knife into his back. But whether he was a fierce defender of freedom or an opportunistic traitor remains a matter of debate.

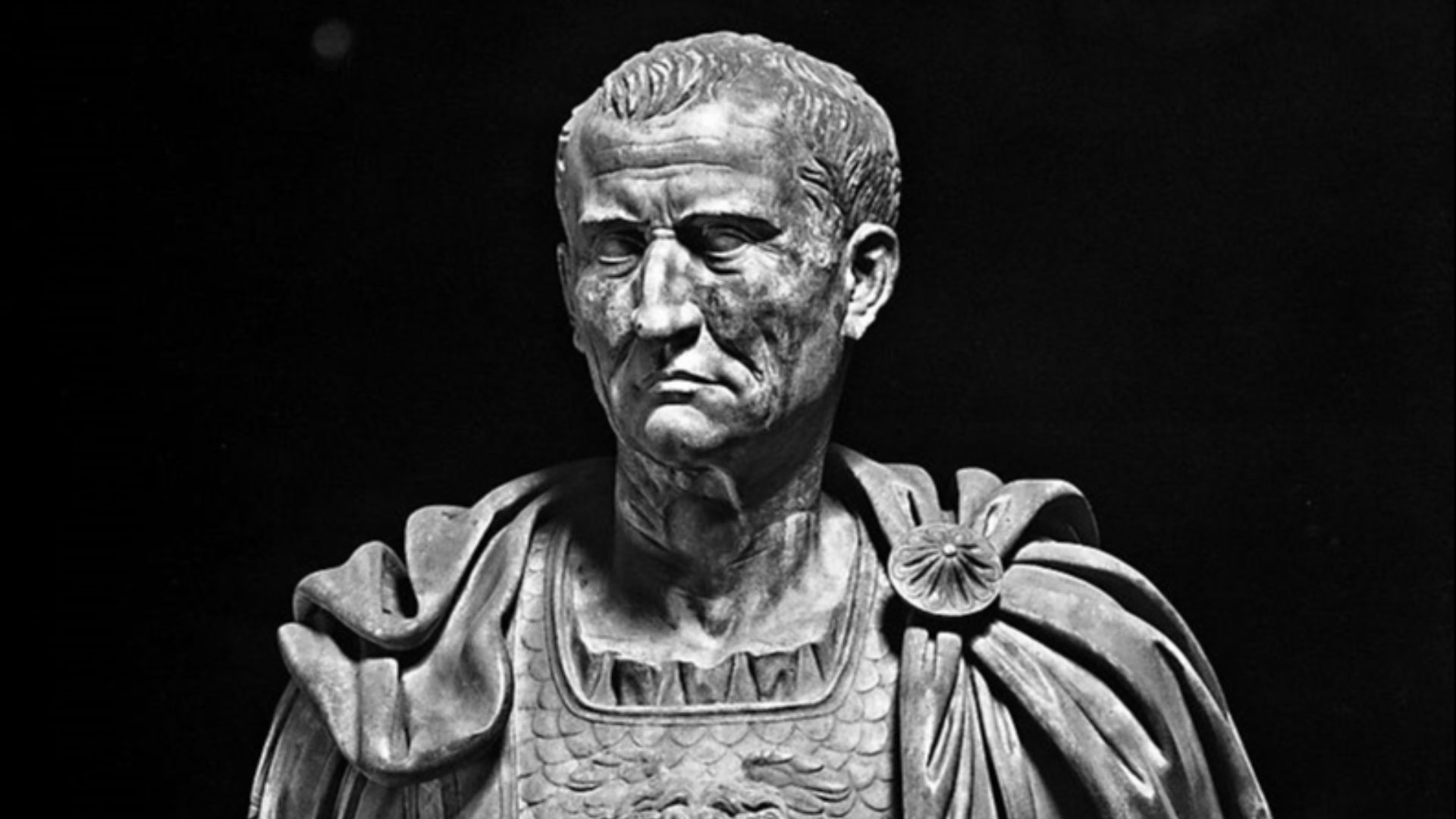

1. He Was Republican Royalty

Marcus Junius Brutus stomped onto the scene around 85 BC with a pedigree that practically screamed destiny. His ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, had overthrown Rome’s last king and became the Republic’s first consul in 509 BC. But young Brutus would soon learn that prestigious bloodlines came with a level of peril.

Rijksmuseum, Wikimedia Commons

Rijksmuseum, Wikimedia Commons

2. His Father Was Betrayed

Given his ancestors’ legacy, Brutus should have been a little more sensitive to betrayal. In 77 BC, his world shattered when Pompey executed his father after promising him safe passage at Mutina. The elder Brutus had surrendered during Lepidus’ rebellion, trusting Pompey’s word—a fatal mistake that left young Marcus fatherless at eight.

It wouldn’t be the last time that Brutus and Pompey crossed paths.

DEA / A. DAGLI ORTI, Getty Images

DEA / A. DAGLI ORTI, Getty Images

3. His Mother Had Scandalous Connections

Brutus wasn’t the only member of his family cozying up to Julius Caesar. His mother, Servilia, became Caesar’s mistress. And the affair set tongues wagging. Some gossipers whispered that Caesar was, in fact, Brutus’ father. However, Caesar had only been fifteen when Brutus was born, so most historians dismiss the claim.

Even so, Brutus and Caesar shared a rocky father-son relationship.

Lionel Royer, Wikimedia Commons

Lionel Royer, Wikimedia Commons

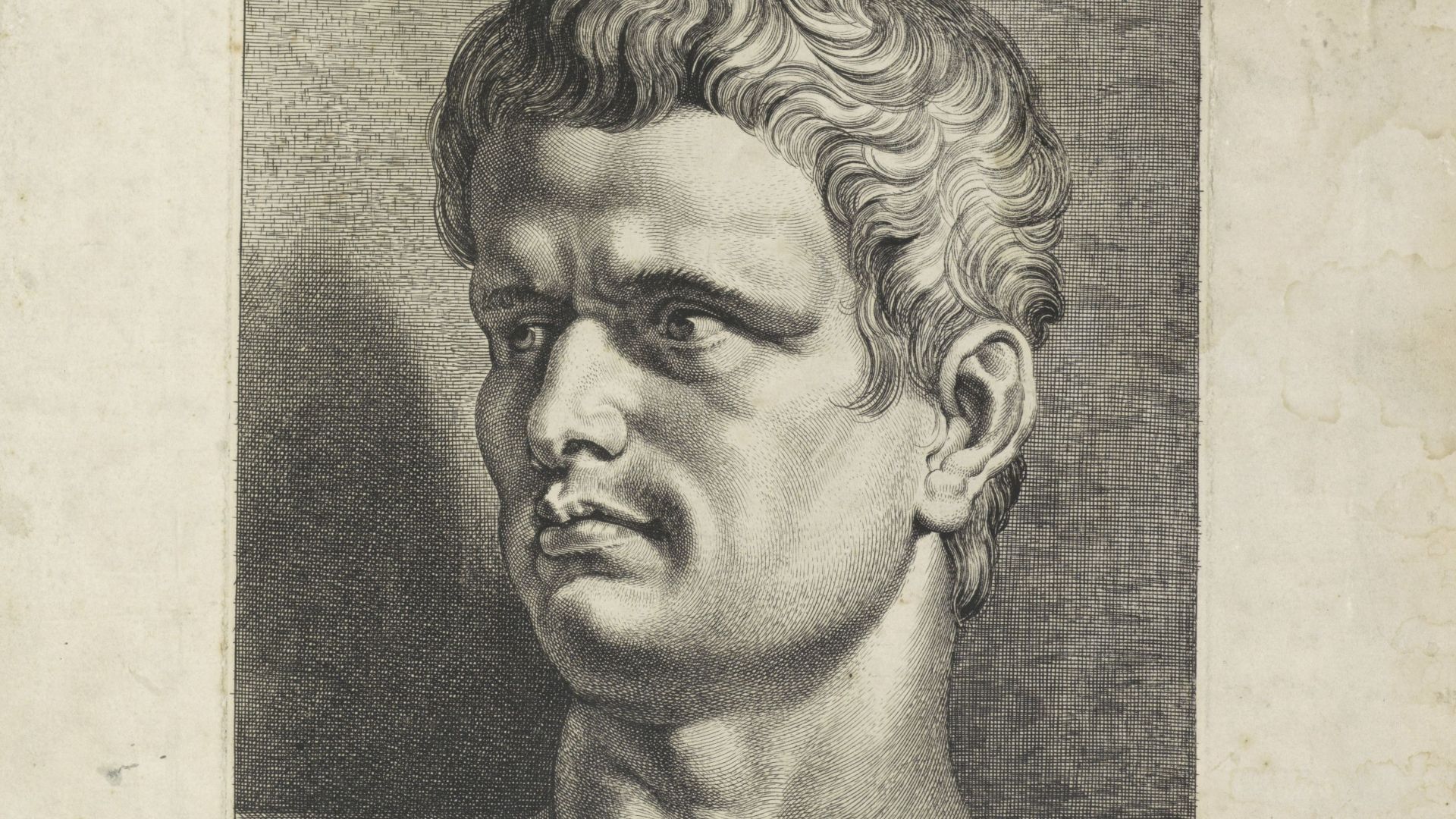

4. He Needed A New Name

Because of his father’s legacy, Brutus could not enter politics. That is, until 59 BC, when he forsook his family name for personal gain. Quintus Servilius Caepio posthumously adopted Brutus, absolving him of his father’s problematic legacy. Brutus officially changed his name to Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus—though he rarely used this mouthful.

The simple legal maneuver opened the doors for Brutus—doors that only led to trouble.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

5. He Faced Early Accusations

In 59 BC, just as Brutus entered public life, he faced his first (of many) political scandals. Lucius Vettius, an informer, named Brutus in a conspiracy to eliminate Pompey in the forum. Given Brutus’ connection to Pompey, it was a plausible accusation. However, when authorities questioned Vettius more closely, the informant mysteriously dropped Brutus’ name from the alleged conspiracy.

Someone powerful clearly protected the young aristocrat from this dangerous entanglement.

George Shuklin, Wikimedia Commons

George Shuklin, Wikimedia Commons

6. He Was A Brilliant Civil Servant

Brutus officially entered the brutal world of Roman politics in 58 BC. His first appointment was simply to serve as Cato’s assistant during the Cyprus governorship. According to the historian Plutarch, Brutus excelled at converting the deposed king’s treasures into practical currency for the booming Roman Republic.

Pretty soon, he had developed a reputation as a competent civil servant. Albeit, one with an agenda.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

7. He Minted Revolutionary Messages

As triumvir monetalis in 54 BC, Brutus controlled Rome’s coin production and used it to make his opinions known. He struck denarii featuring his tyrannicide ancestors Lucius Junius Brutus and Gaius Servilius Ahala, both celebrated as champions of the Roman conception of liberty.

These coins sent a clear message about where his loyalties lay in Rome’s political struggles. And the lengths he would go to defend them.

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, Wikimedia Commons

Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com, Wikimedia Commons

8. His Coins Challenged Pompey

Brutus’ second coin design featured Libertas herself (the Roman goddess of liberty) alongside Lucius Brutus. The design, however, had some hidden meaning. The bold propaganda was a direct challenge to Pompey’s growing ambitions for sole rule over the Roman Republic. In the meantime, Brutus was seizing power of his own.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

9. He Married Into Power

In 54 BC, Brutus upped his game. He tied the knot to Claudia, the daughter of consul Appius Claudius Pulcher, cementing a crucial political alliance in his rapid rise to prominence. The next year, he leveraged the power of his new in-laws, getting elected as quaestor. Serving under his father-in-law, he gained enrollment in the senate in Cilicia.

Once he had power, he became the very thing he once dreaded: a tyrant.

Unknown 1915, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown 1915, Wikimedia Commons

10. He Had An Interest In Interest

While in Cilicia, Brutus arranged usury loans at a staggering 48 percent annual interest—four times the cap set by Cicero. To circumvent the law, he used his friends’ names, then leveraged his new senate connections to confirm his questionable contracts. But even if he acted like a tyrant himself, there was one tyrant he couldn’t tolerate.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

11. He Defied Pompey’s Power

As Brutus continued to rise in prominence, he wasn’t shy about wanting to even the score with the man who had ended his father’s life: Pompey. Believing that the pen was mightier than the sword, he penned De Dictatura Pompei, fiercely opposing calls for Pompey’s dictatorship. “It is better to rule no one than to be another man’s slave,” Brutus wrote, “for one can live honourably without power but to live as a slave is impossible”.

His words would prove prophetic in ways he couldn’t imagine.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

12. He Outwitted His Uncle

Not everyone in Brutus’ clan shared his political beliefs. Cato the Younger, his mother’s half-brother, backed Pompey’s sole consulship, claiming “any government at all is better than no government". Brutus, however, held firm against one-man rule. Still, a clear schism was beginning to form. A schism that would cause the deepest betrayals in all of ancient history.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

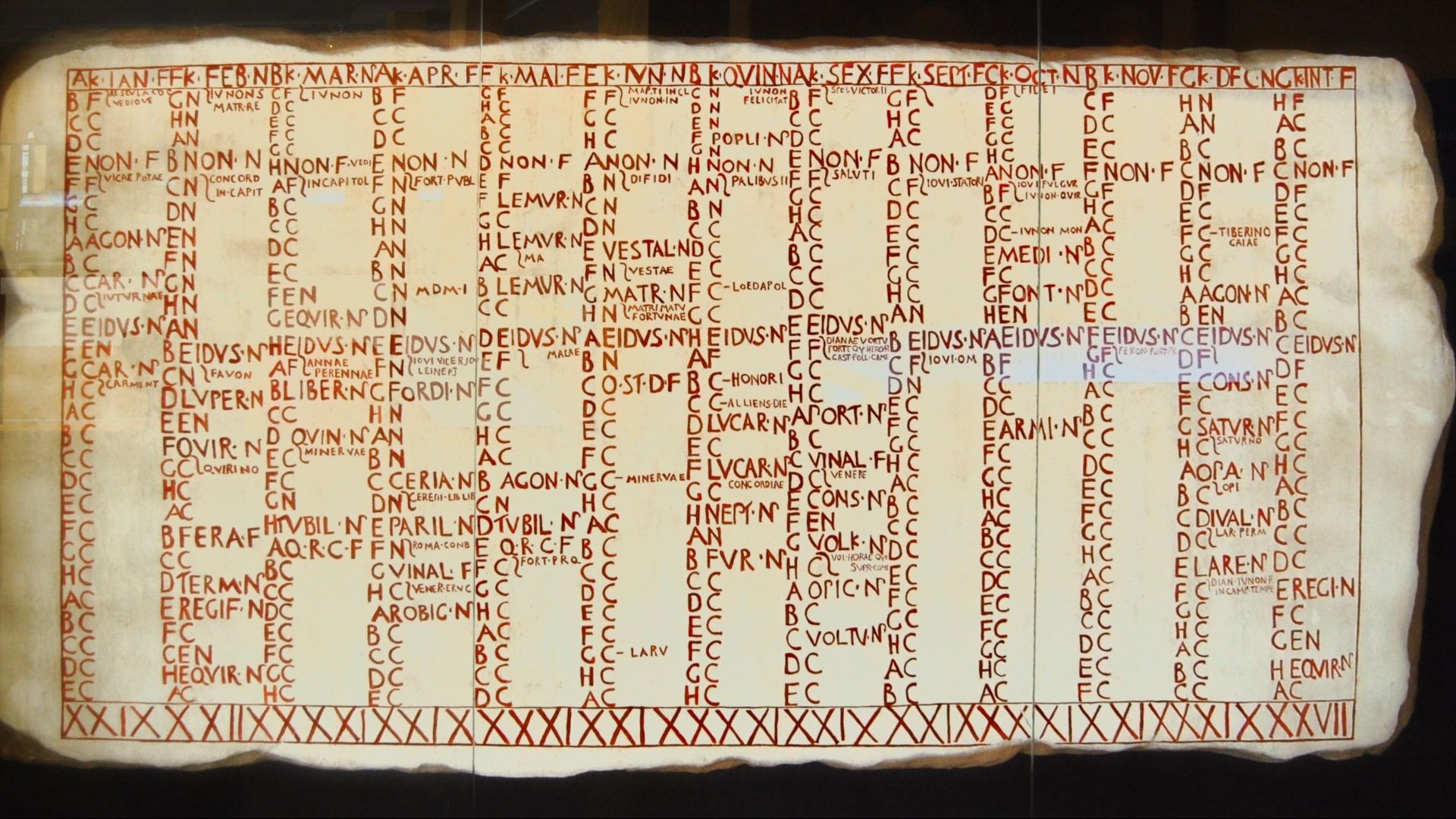

13. He Was In Charge Of The Calendar (And The Gods)

Brutus wasn’t just a savvy politician. He was a deep believer in Roman tradition. When he was elected as pontifex, Brutus effectively assumed responsibility for Rome’s sacred calendar and worked to keep the Roman gods happy with the people. Brutus likely only got the all-important appointment thanks to support from none other than Julius Caesar.

He had a funny way of showing his thanks.

14. He Sided With His Mortal Enemy

In January of 49 BC, Julius Caesar made his move to seize control of Rome. Shockingly, Brutus sided with his mortal enemy over his political benefactor. In the opening days of the conflict, Brutus supported Pompey, the man who had executed his father. But his reasons were probably self-preservation. All of his closest allies—Appius Claudius, Cato, Cicero—had sided with Pompey.

The uneasy alliance couldn’t last forever.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

15. He Begged For Caesar’s Mercy

After Caesar crushed Pompey in battle at Pharsalus, Brutus saw the tides turning—and decided to swim to the winning side. He fled through the marshes to Larissa and wrote to Caesar, seeking clemency for his betrayal. Plutarch recorded Caesar’s orders: capture Brutus if he surrendered voluntarily, but leave him unharmed if he resisted.

Caesar’s extraordinary mercy would haunt both men forever.

Cassell's illustrated universal history, Wikimedia Commons

Cassell's illustrated universal history, Wikimedia Commons

16. He Became Caesar’s Peacemaker

While Caesar hunted down Pompey to Alexandria, Brutus worked tirelessly trying to bring Pompey’s allies to Caesar’s side. Clearly, he was successful. When Brutus returned to Rome, Caesar gave Brutus a major promotion, naming him as Cisalpine Gaul’s governor.

It seemed that Caesar and Brutus had worked out all their differences.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

17. He Ditched His Wife For A Better One

When Caesar scored his final victory over his opponents in March 45 BC, Brutus was busy making new alliances of his own. In an inexplicable move, Brutus divorced Claudia and immediately married his cousin Porcia, Cato’s daughter. The hasty switch shocked Roman society. The fallout nearly ended Brutus’ new alliances.

Elisabetta Sirani, Wikimedia Commons

Elisabetta Sirani, Wikimedia Commons

18. His Marriage Sparked Family Feuds

Brutus’ failure to provide a reason for his divorce and remarriage created a “semi-scandal”. Worse yet, Brutus’ mother, Servilia, and his new wife, Porcia, despised each other. Their open mutual disdain and resentment poisoned Brutus’ careful allegiances. Defending his family’s name would prove harder than he thought.

Trailer screenshot, Wikimedia Commons

Trailer screenshot, Wikimedia Commons

19. He Faced Ancestral Pressure

By autumn 45 BC, Brutus’ family legacy of tyrannicide clashed with his friendship with Julius Caesar. So, when graffiti glorifying Lucius Junius Brutus appeared everywhere, mocking Caesar’s royal ambitions, things got awkward. Brutus was taunted and mocked in the courts for his obsequiousness towards Caesar.

Either he would have to betray his family’s legacy—or he would have to betray his closest political ally.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

20. He Sat By As Caesar Was Crowned

By early 44 BC, Julius Caesar had become so popular that even the people of Rome clamored for him to become king. After feigning to refuse Antony’s crown three times, Caesar finally accepted it—along with the title dictator perpetuo (dictator for life). Seeing this shocking development, Cicero wrote to Brutus, urging him to cut ties with Caesar.

What happened next is a matter of historical debate.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

21. He May Have Started The Whole Conspiracy

Brutus may have started the whole conspiracy that ultimately led to Caesar’s demise. However, different sources give different accounts. Cassius Dio, for example, claimed that Brutus’ wife drove him to dream up the plot. Even Plutarch backed up this version of events. But Appian and Dio insisted that it was Cassius who made the first move.

Either way, Brutus had made his decision—and Caesar would pay the price.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

22. He Built A Dangerous Alliance

By February of 44 BC, Brutus and Cassius were recruiting conspirators. Even Decimus Junius Brutus—Caesar’s own cousin and trusted ally—flipped sides. Thanks to oratorical skills, political savvy, and dedication to Roman liberty, Brutus drew in powerful allies like Gaius Trebonius, Publius Servilius Casca, Servius Sulpicius Galba, and others.

The plot against Caesar was no longer a conspiracy. It was an inevitability.

23. He Spared Mark Antony

When the conspirators debated eliminating Antony alongside Caesar, Brutus’ true colors showed. He forcefully objected, believing, as Plutarch did, that the conspirators could convince Antony to join their cause. Other conspirators, however, questioned Brutus’ dedication to the cause of tyrannicide.

He would prove his commitment to freedom in blood.

William Hilton, Wikimedia Commons

William Hilton, Wikimedia Commons

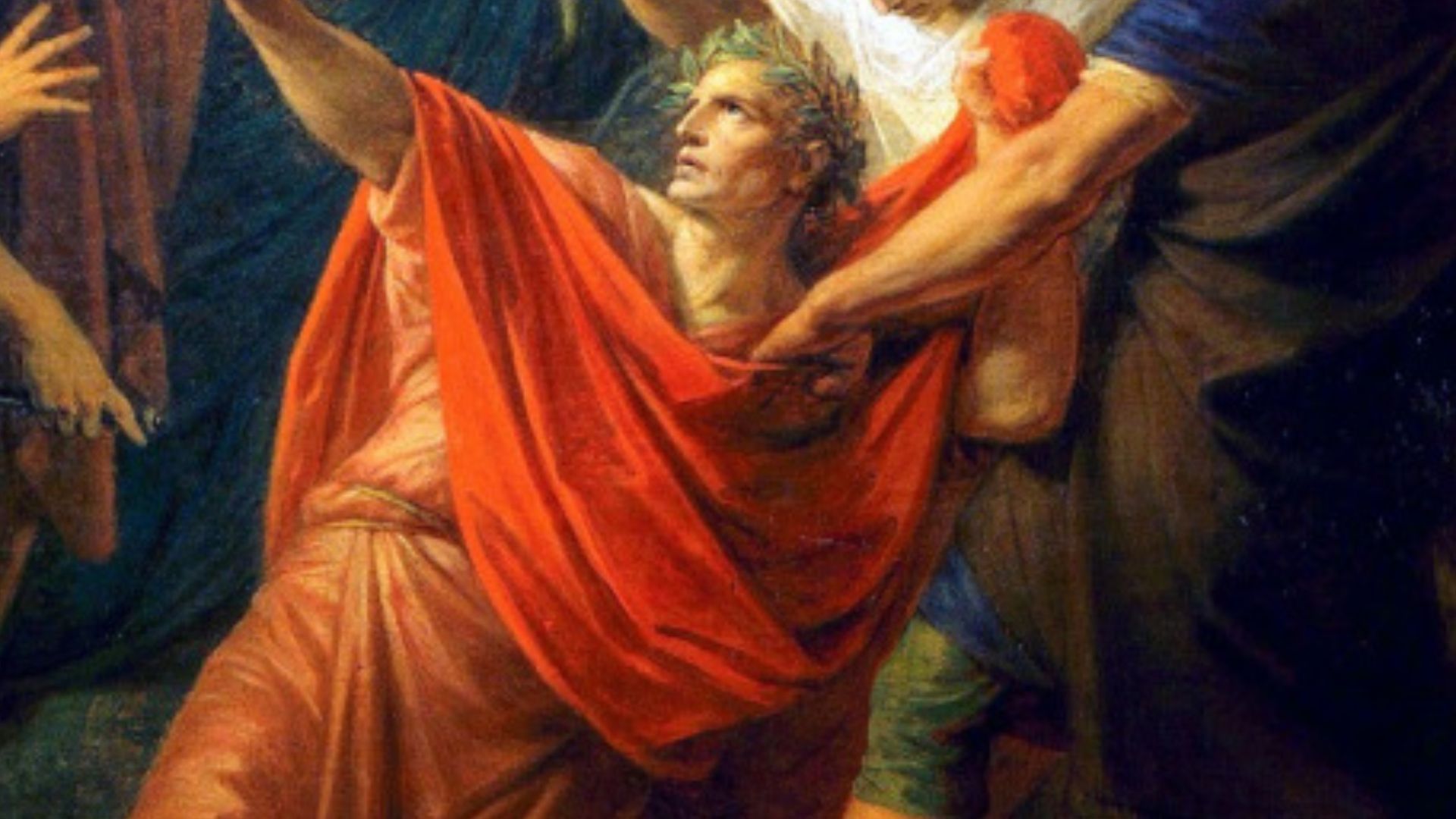

24. He Struck On The Ides

The Ides of March—March 15—in 44 BC arrived. The day had finally come for Brutus to live up to his legacy. Different historical sources list varying numbers of conspirators, ranging from 15 to 80. But the result was the same. During a senate meeting, the conspirators cornered Caesar in Pompey’s Curia and struck.

Caesar suffered between 23 and 35 stab wounds, sealing his grim fate. One wound, however, cut deeper than the rest.

Heinrich Fuger, Wikimedia Commons

Heinrich Fuger, Wikimedia Commons

25. He Broke Caesar’s Heart

Plutarch claimed that Caesar stopped fighting against his assailants after spotting Brutus among them. Somehow, Caesar’s words to his trusted friend and political son cut even deeper than a dagger. Speaking in Greek, Caesar is reported to have said, “kai su teknon”—”You too, child?” Those famous last words meant more than they suggested.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

26. He May Not Have Had A Chance To Say Goodbye

While most historical accounts retell the events of the Ides of March ending with a cutting remark from Caesar to Brutus, another account is less poetic. Suetonius suggested that Caesar fell in silence, claiming that the dramatic quote, “kai su teknon”, was nothing more than a normal Roman literary flourish.

Whether Caesar truly spoke those words remains a mystery. The answer, however, doesn’t change the outcome.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

27. He Left Caesar’s Body

As Caesar, the great and terrible tyrant, fell at the base of Pompey’s statue, pooled in his own blood, terror gripped the senate chamber. Senators scattered like frightened birds, abandoning the dictator’s corpse until darkness fell. Brutus, seeing the chaos, knew that he had to act.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

28. He Rallied The People

Once their bloody deed was complete, Brutus and the other conspirators marched straight to the Capitoline Hill, the religious and political center of the Republic. It was there that Brutus delivered a riveting speech to the stunned citizens of Rome. Sadly, his exact words have vanished into history.

Whatever he said, however, paved the way for a tyrant-free future.

Jean-Pierre Dalbera from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Pierre Dalbera from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

29. He Wanted Reconciliation, Not Revolution

Once the initial pandemonium settled, Brutus and Cassius plotted another kind of conspiracy: reconciliation, not revolution. Together, they hammered out terms for post-Caesar Rome: amnesty for the conspirators, confirmation of Caesar’s appointments for two years, land grants for Caesar’s veterans, and a public funeral.

The compromise aimed to prevent further unrest—but Brutus wasn’t ready for what came next.

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

30. He Underestimated Antony

Caesar’s funeral, held five days after Brutus’ betrayal, became another turning point. Antony’s emotional eulogy heaped scorn on Brutus and his conspirators, souring public sentiment against the tyrannicides. Even as tensions bubbled up again, Brutus remained in Rome for several more weeks. Still, even he had to admit: the tide had turned against him and his fellow conspirators.

Rome was no longer safe for a traitor.

George Edward Robertson b. 1864, Wikimedia Commons

George Edward Robertson b. 1864, Wikimedia Commons

31. He Retreated From Rome

A few weeks after Brutus’ betrayal of Caesar, public sentiment on the streets of Rome had turned against him. He knew he had to escape—but he couldn’t be seen fleeing. So Brutus leveraged his power as urban praetor and secured a special permission to leave the capital city beyond the usual 10-day limit. Brutus then absconded to his Lanuvium estate, 20 miles southeast of Rome.

He’d soon learn; even that wasn’t far enough.

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

32. He Fled Italy

By August of 44 BC, sentiment against Brutus and the other conspirators had only grown worse. Brutus had no choice but to flee Italy altogether. Thankfully, when he arrived in Greece, the people greeted him as a freedom fighter. At Athens, eager students and nobles alike pledged their loyalty, swelling his ranks.

But adoration was a dangerous thing—and Brutus was hooked.

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

33. He Captured A Powerful Hostage

Fearing for his safety and the security of the Roman Republic, Brutus marched his forces into Macedonia, where he made a bold move. As an insurance policy, Brutus captured Antony’s brother, Gaius. At that moment, the senate still backed Brutus and Cassius, officially granting them command over Macedonia and Syria.

Power granted by politicians, however, rarely lasts for long.

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

34. His Alliances Crumbled

While Brutus had taken command of powerful Roman provinces, his own world was collapsing. First, his half-brother-in-law, Lepidus, sided with Antony against the tyrannicides. Then, worse still, Brutus’ beloved wife, Porcia, passed on. With his personal alliances crumbling, Brutus could feel his opportunity slipping away.

Henry Courtney Selous, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Courtney Selous, Wikimedia Commons

35. He Became An Outlaw

The summer of 43 BC turned into Brutus’ worst nightmare. Back in Rome, Octavian stormed into power and forced (at the point of a sword) his own election as consul. Then came the knockout blow for Brutus: the lex Pedia. The law immediately branded Brutus and his co-conspirators as outlaws for what they did to Caesar.

Once a hero, Brutus was now a hunted man.

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

36. His Enemies Joined Forces

Brutus’ fortunes took an even more dire turn when Caesar’s former allies—Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus—buried their feuds and formed the Second Triumvirate. Their brutal campaign wiped out hundreds of anti-Caesarians, Cicero among them. When word reached Brutus, he knew he had to act.

Brutus immediately crossed the Hellespont in a vengeful fury, subduing rebels and crushing cities across Thrace. But vengeance only breeds more enemies.

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

37. He Became The Tyrant

Brutus’ desperate situation drove him to desperate measures. In early 42 BC, he joined forces with Cassius and launched a merciless campaign across Asia Minor. With Cassius, he plundered towns that had aided their foes, selling entire populations into bondage. This dark chapter in Brutus’ story led many to call him a hypocrite, accusing him of the same tyranny for which he had plotted against Caesar.

His guilt was overwhelming.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Wikimedia Commons

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Wikimedia Commons

38. He Wept (Tears Of Silver And Gold)

Other writers, like Plutarch, tried to rehabilitate Brutus’ image. They claimed that Brutus could not have been a tyrant as he had broken down in tears over the devastation he caused in Asia Minor. Whether true or not, such “noble remorse” made for good propaganda. Plus, Brutus had plundered untold riches from his campaign, easing any guilty conscience he might have had.

He would need more than money to survive what came next.

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

Screenshot from Julius Caesar, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (1953)

39. He Bought Loyalty

Eventually, Brutus and his allies converged with Octavian and Antony and their allies. The two Roman factions squared off with roughly equal numbers. Brutus hoped that his new riches would buy his troops’ loyalty, shelling out 1,500 denarii upfront. But gold, as he was about to learn, could buy loyalty, just not fate.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

40. He Won, But His Allies Lost

The first battle of Philippi erupted—and it was a nail-biter from the beginning. In a move of stunning genius, Brutus’ right flank overwhelmed Octavian’s troops, looting the young Caesar’s camp and forcing him to retreat. But on the opposite field, Cassius’ men broke beneath Antony’s assault. Victory on one side meant nothing if defeat claimed the other.

Pauwels Casteels, Wikimedia Commons

Pauwels Casteels, Wikimedia Commons

41. He Sent Mixed Signals

After the first clash, chaos and miscommunication led to a Romeo & Juliet situation. Cassius’ messenger failed to deliver news of Brutus’ triumph on the other side of the battlefield. This failure in communication led Cassius to believe that all was lost. Stricken by despair, he ended his own life. When Brutus learned what had happened to his greatest ally, he knew he had to act fast.

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons

42. He Took Command Of The Fallen

After Cassius’ demise, Brutus didn’t weep—he rallied. Assuming command of his ally’s forces, he promised his weary men both glory and gold if they picked up their swords and fought with him. Allegedly, he even vowed to let them plunder Thessalonica and Sparta for their loyalty. Hope returned to his camp—but so did hubris.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

43. He Gambled It All

Knowing that a pitched battle would risk his own life, Brutus wanted to starve his enemy into submission. But fear gnawed at his ranks as rumors of desertion spread amongst Brutus’ camp. Meanwhile, Antony threatened to cut off his supply lines. Desperate, Brutus abandoned patience and marched straight into the second battle of Philippi.

The result was carnage on a cosmic scale.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

44. He Faced The End Alone

When the dust settled, Brutus’ grand gamble had failed. With his legions shattered, he fled into the hills with a few loyal fighters for Roman liberty left at his side. Knowing capture meant humiliation (or worse), Brutus chose an honorable exit. With steady resolve, he fell upon his own sword.

The defender of liberty had finally freed himself—from life.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

45. He Gave A Final Command

According to Plutarch, Brutus met his end like a true Roman citizen should: with words of freedom echoing through history. “By all means must we fly,” Brutus said calmly, “but with our hands, not our feet”. He thanked his followers for standing by him and urged them to escape while they could. He had less inspiring words for his enemies.

Weston, W H; Plutarch; Rainey, W, Wikimedia Commons

Weston, W H; Plutarch; Rainey, W, Wikimedia Commons

46. He Cursed The Victors

Moments before his fatal plunge, Brutus quoted Euripides, cursing his enemies and the tyrants that would rule over Rome in the centuries to come. Crying out, he said, “O Zeus, do not forget who has caused all these woes”. For his steadfast dedication to the Roman conception of liberty, even Brutus’ enemies had to honor him.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

47. His Enemy Showed Him Honor

When Antony found Brutus’ lifeless body, he refused to gloat. Instead, he draped it in his finest purple mantle—the color of kings—and ordered a proper cremation. The ashes, he said, would be sent to Servilia, Brutus’ grieving mother. Mercy, it seemed, had won the day. However, not all agreed with honoring Brutus in this way.

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

AnonymousUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

48. He Lost His Head At Sea

Unlike Antony, who honored Brutus’ legacy, Octavian had no such sentimentality. According to Suetonius, in a different account of the events following the second battle of Philippi, Octavian severed Brutus’ head and planned to display it before Caesar’s statue as a gruesome warning to future tyrannicides. Legend has it, however, that a terrible tempest tossed Brutus’ head into the Adriatic before Octavian could bring it back to Rome.

That wasn’t the worst insult to his memory.

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

Screenshot from Rome, HBO (2005-2007)

49. His Name Became A Curse

Time has not been kind to poor Brutus. In various languages across Europe, his very name has become another word for “traitor.” In Dante’s Inferno, Brutus shares Hell’s lowest circle with Cassius and Judas Iscariot, forever chewed in Satan’s jaws for betraying their masters. Still, his passion for liberty might have saved him from the pits of Hell.

VladoubidoOo, Wikimedia Commons

VladoubidoOo, Wikimedia Commons

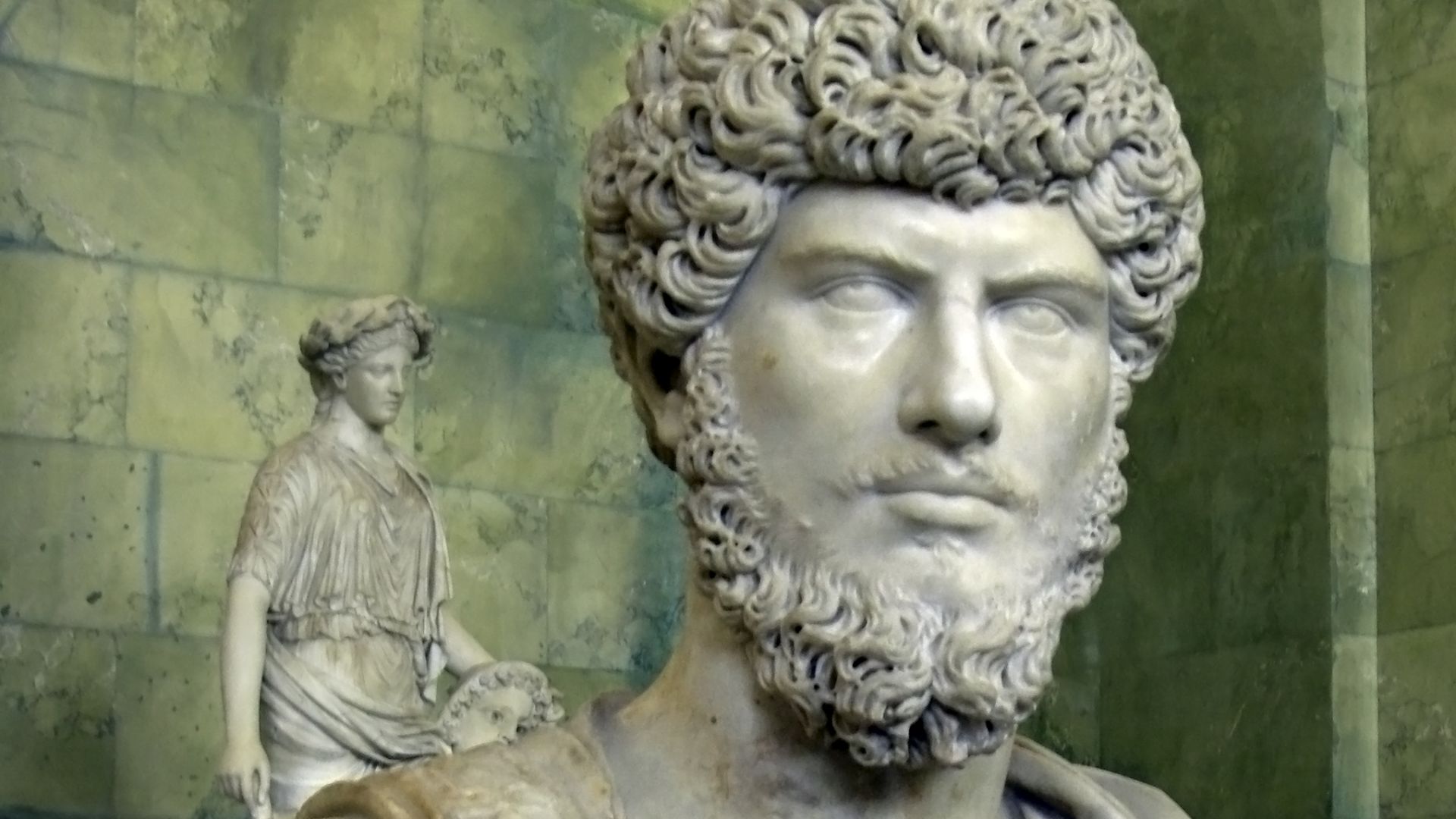

50. He Was Also A Martyr

Not everyone thought of Brutus as a traitor to Caesar. Throughout history, to philosophers and poets alike, Brutus has remained the man who dared to defy tyranny. They saw not a villain but a visionary—one who chose principle over power. His contemporaries seem to have thought highly of him.

Otto Sarony, Wikimedia Commons

Otto Sarony, Wikimedia Commons

51. His Betrayal Was Noble

In the end, even Brutus’ enemies admitted his virtue. “Brutus was the only man to have slain Caesar because he was driven by the splendour and nobility of the deed,” Antony supposedly said, "while the rest conspired against the man because they hated and envied him". Backstabber, betrayer—liberator.

Otto Sarony, Wikimedia Commons

Otto Sarony, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

The Bloody Secrets Of The Woman Behind The Taj Mahal

King Edward III May Have Saved England—But He Still Met A Pitiful End