Marie Curie requires little introduction: her name itself has become a shorthand for the archetypical super-smart and trailblazing female scientist. The Polish-born scientist formed one-half of the Curie power couple, who went on to win the Nobel Prize for their discovery of radium. And she didn’t stop there: in her widowhood, Curie went to win another Nobel prize, thereby cementing herself in history as a role model for women in STEM.

Behind her scientific honors, however, there lays a historical struggle. For the Marie, the path to knowledge was fraught with starvation, sexism, war, love, and, yes, the occasional sex scandal. Raised in a time and place where higher education for women was not just taboo but often illegal, no one can accuse Marie Curie of having an easy walk to the podium. Strap on those safety gloves to these 42 explosive facts about Marie Curie.

“Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood. Now is the time to understand more, so that we may fear less.”—Marie Curie.

Marie Curie Facts

42. Took You Long Enough

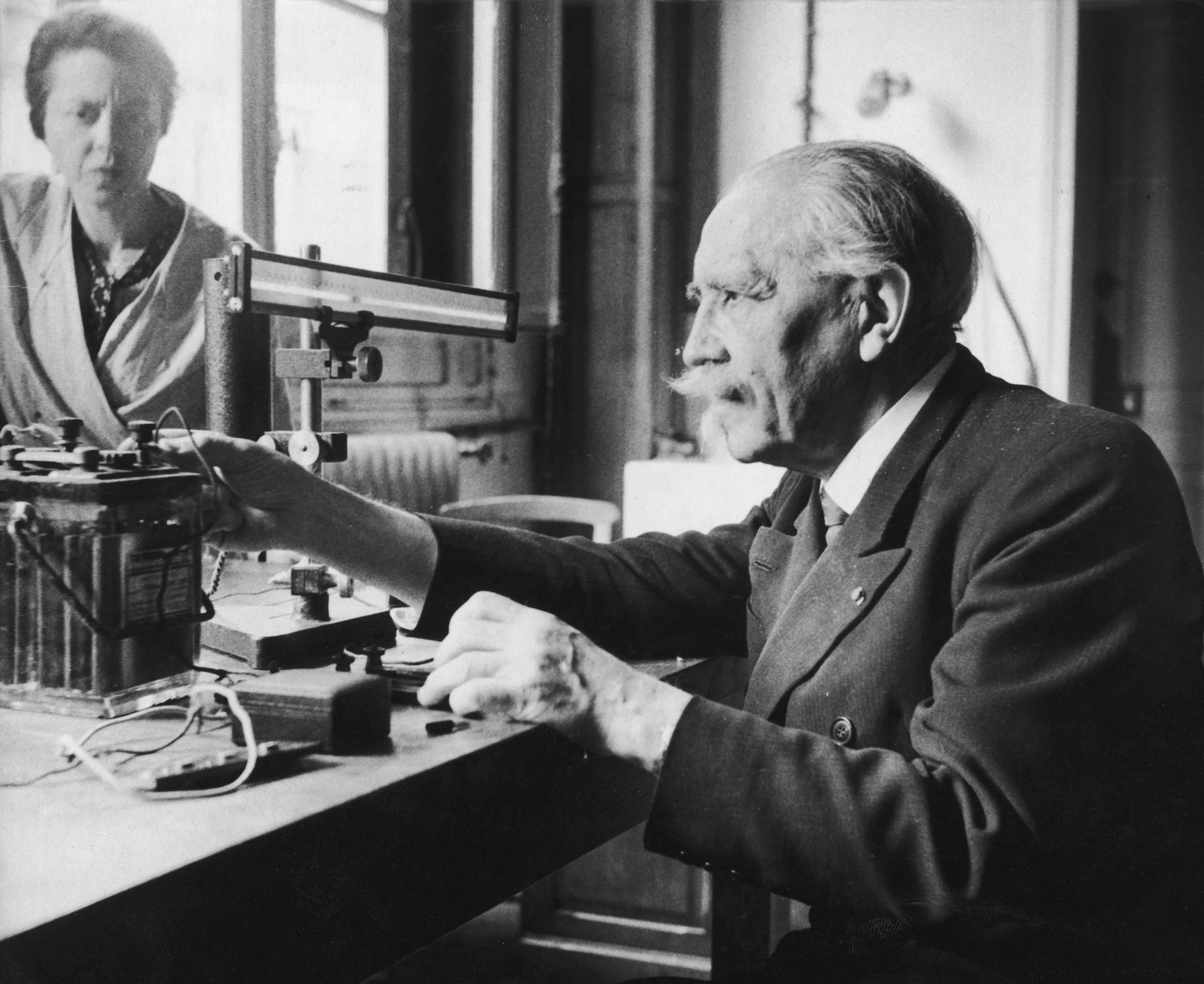

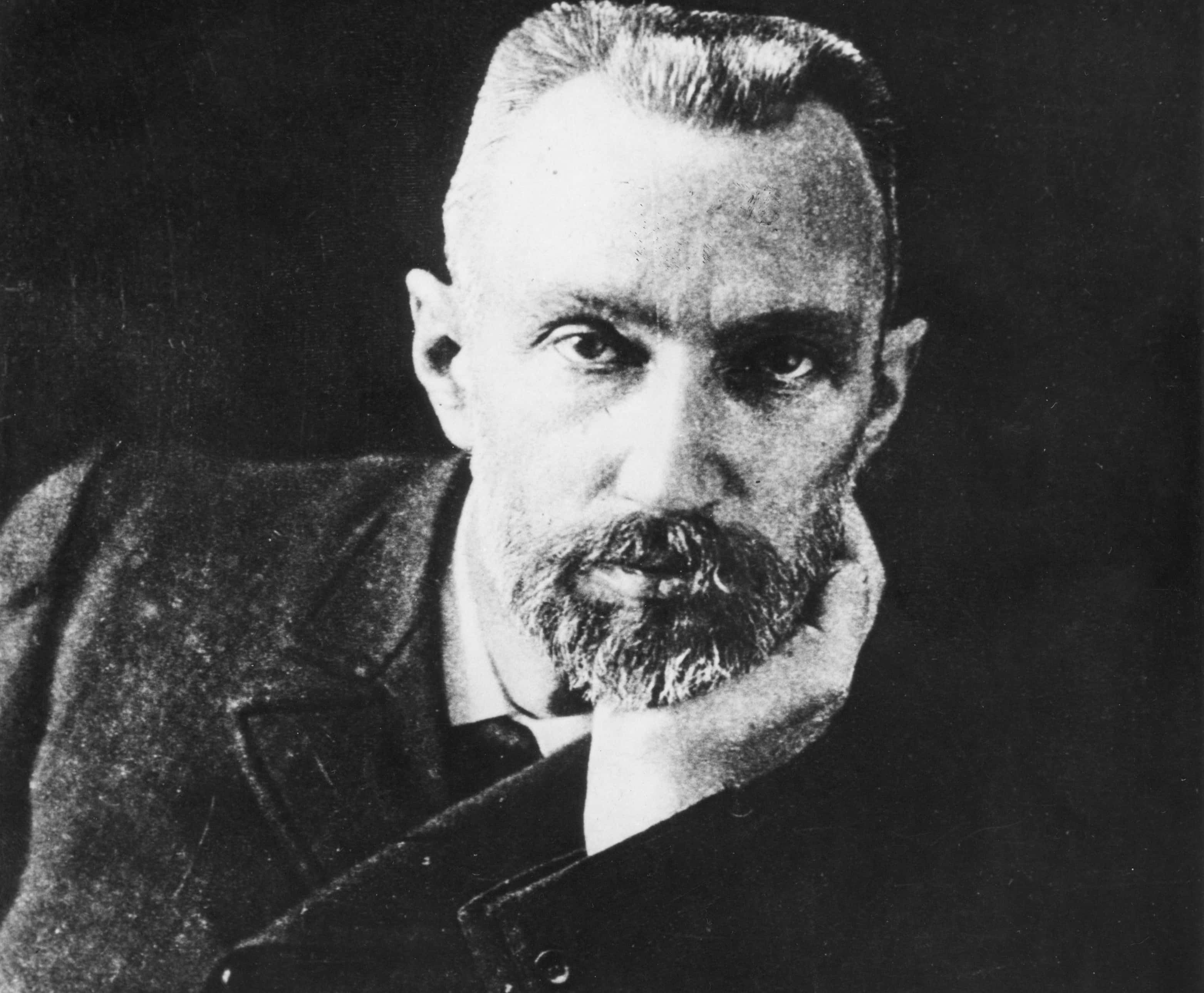

To little surprise, Curie’s career marks a lot of firsts for French women. In 1906, she became the first female professor at the University of Paris. Originally, the physics department had created the Chair position for Marie’s late husband, Pierre, and retained it after his death. Finally, they offered it to his equally brilliant wife, Marie.

41. The Last First

Curie didn’t let a thing like death stop her from coming in first. In 1995, the Panthéon in Paris entombed Curie’s body—which makes her the first woman to reside there on her own merits (as opposed to marrying in). She remains interred, together forever, next to her husband, Pierre.

Flickr

Flickr

40. Humble Beginnings

Marie Curie was born in 1867 as Maria Sklodowska. She was the fifth and youngest offspring of Bronisława and Wladyslaw Skłodowski, two respected teachers who had lost their family fortunes in the 19th century Polish national uprisings. As a result, Maria and her siblings would inherit little from their family, save for a vast love of learning.

39. Running out of Faith

For a time, Marie Curie grew up in a multifaith household: her mother Bronisława was a devout Catholic, while her father Wladyslaw Skłodowski was an atheist. After the heartbreaking sudden death of both her mother and oldest sibling Zofia from illnesses, the future scientist gave up her mother’s religion and turned towards agnosticism.

38. Science vs. Severance Package

Curie’s father stole lab equipment from his teaching job. But it was for a noble cause: the Russian government had shut down labs in Polish schools, so Wladyslaw smuggled supplies home to teach his children for themselves. Eventually he was fired for his political views, so the family operated a boarding house to make a living for some time.

37. Speak No Evil, Take No Offense

Marie wasn’t allowed even talk during her own 1903 speech to the Royal Institution in London. Right after getting her PhD, Marie and her husband were invited to speak on radioactivity. The hitch: women weren’t allowed to speak there, so Pierre had to do all the talking.

36. The Bank of Dad

To fund their educations, Marie and her older sister Bronisława cut a deal: Bronisława would finish medical studies in Paris with Marie helping them out financially. After two years, Bronislawa would do the same for her. Bronisława became a respected doctor in her own right. She eventually became the first director of Warsaw’s Maria Skłodowska-Curie Institute of Oncology, then known as the Warsaw Radium Institute. Of course, Bronisława also got married and while she invited her little sister Marie to finish her studies with them in Paris, Marie had to be partially helped by their father to pay the steep tuition.

35. Starving Scholar

School in Paris was not as charming as it sounds. As Marie studied physics, chemistry, and math at the University of Paris in 1891, she was living on so little that she often fainted from hunger. Learning by day, tutoring by night, Marie barely made it out alive; but she finally won her degree in physics in 1893.

34. Funding Is Love, Funding Is Life

After practically almost starving to death to earn her first degree in 1893, Marie went back to school for a second degree the next year—this time she got a fellowship.

33. In the Wings of Knowledge

While it wasn’t financially easy for Marie and her sister to get an education, it was also legally dangerous. At the time, higher learning for women was actually illegal in Poland, so it goes without saying that the University of Warsaw didn’t accept ladies. Instead, Marie and Bronisława got their scholastic head start in an illegal women’s institution called the “Flying University”—so named because it was ‘fly by night’ and always changing locations to outrun the law.

32. Beat That

Most remember Marie Curie as the first woman to win the Nobel Prize in 1903—a physics award that she shared with her husband, Pierre, for their work on radioactivity. To this day, she remains the only person ever to win two Nobel Prizes in separate science categories. She won again in 1911 for chemistry.

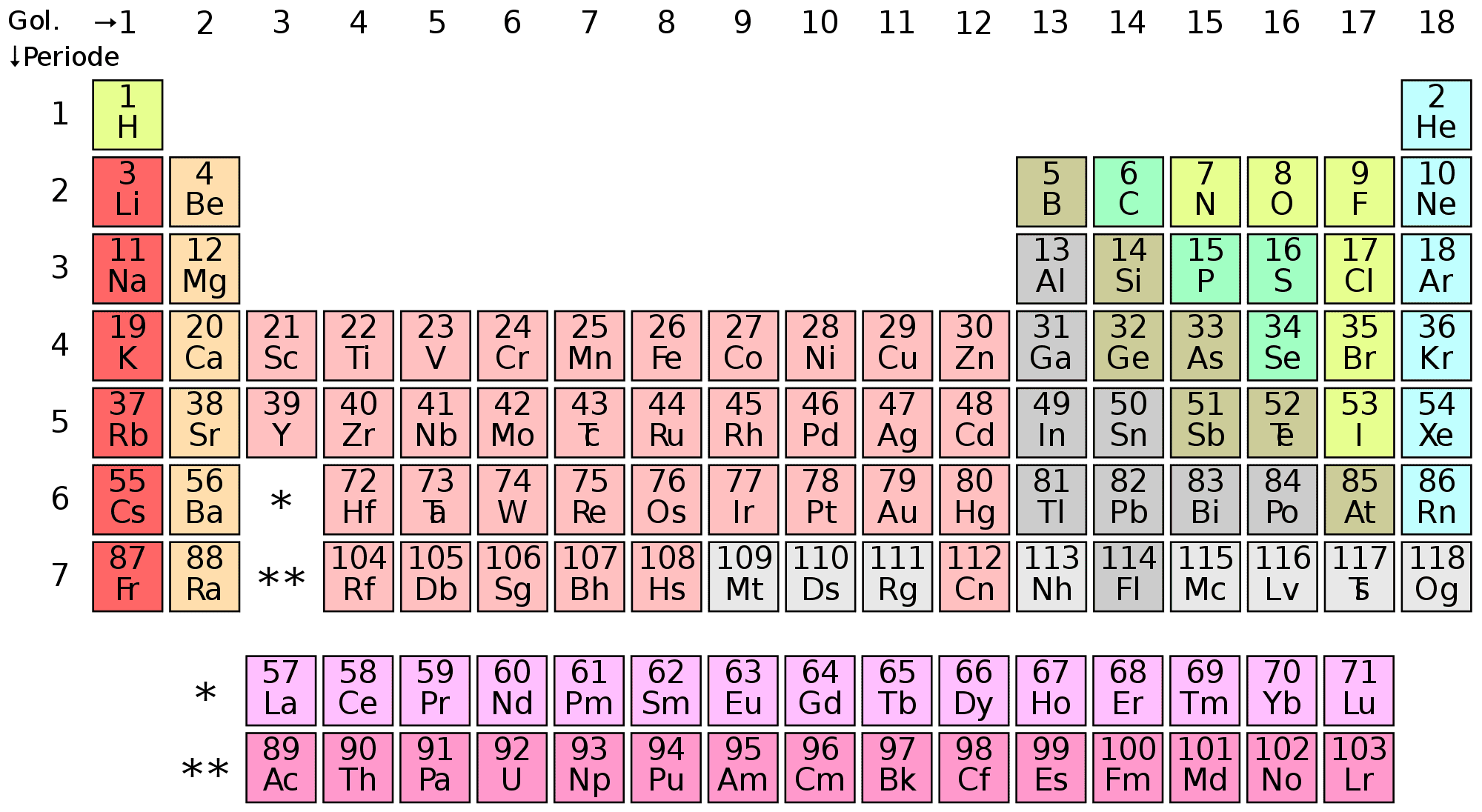

31. The Fifth (and Sixth) Element

Where would “radium” and “polonium” be without Marie Curie? Answer: probably not on the Periodic Table. Thanks to Curie, these two elements were immortalized in that fabled science chart; “radium” was named named after the Latinate term for “ray” and “polonium” named after her Polish motherland.

30. A Mom and Pop Operation

Irène Curie was just 6 years old when her parents, Marie and Pierre, won their first Nobel Prize in 1903. In 1935, Irène kept up the family winning streak by nabbing the Nobel Prize for chemistry with her own husband, Frédéric Joliot-Curie. They discovered “artificial” radioactivity, which built upon the research of her parents.

29. Diversify Your Nobel Portfolio

On the other side of Marie’s family, she had a son-in-law, Henry Labouisse, who won the Nobel Peace Prize on UNICEF’s behalf in 1965. It’s not a STEM award, but hey, it brought up their prize winner dynasty to a score up to five. That’s what matters.

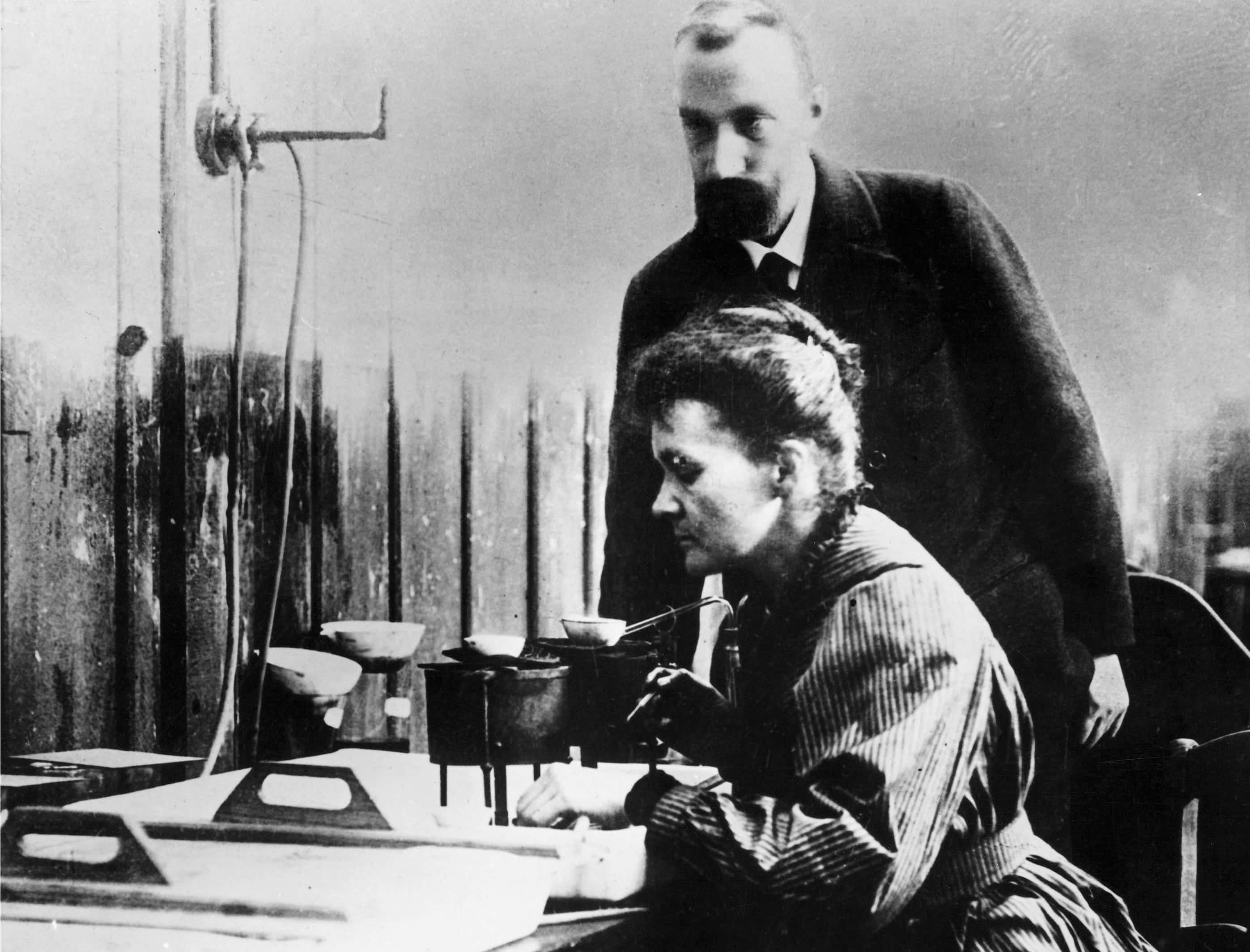

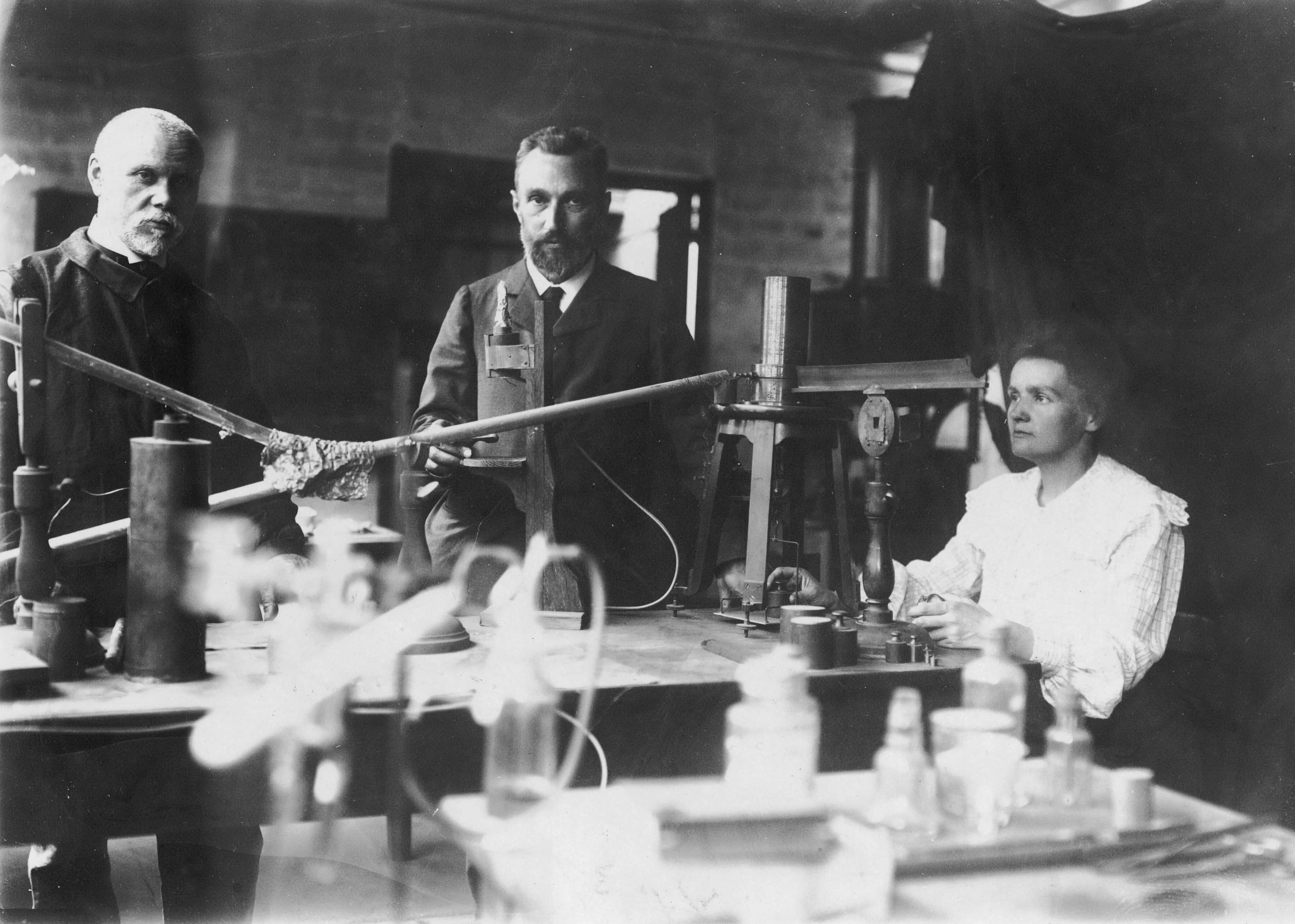

28. Welcome to the Love Shack

Marie and her husband partly completed their prize-winning experiments in an old shed behind a school. The old labs at work just couldn’t house all the equipment that the Curies required to break down ore. The shack was not well ventilated, and the roof leaked frequently; one visitor described the shed as "a cross between a stable and a potato shed, and if I had not seen the worktable and items of chemical apparatus, I would have thought that I was been played a practical joke." Hey, one person’s creepy shed is another science couple’s genius love shack.

27. The Silent Struggle

After her mother’s death, Marie Curie would experience long struggles with mental illness. Although she graduated from a gymnasium school (a type of school with a strong emphasis on academic learning) with a gold medal in 1883, she collapsed from possible depression soon after and had to take a “gap year” of sorts, where she tutored and recovered in the country with her relatives.

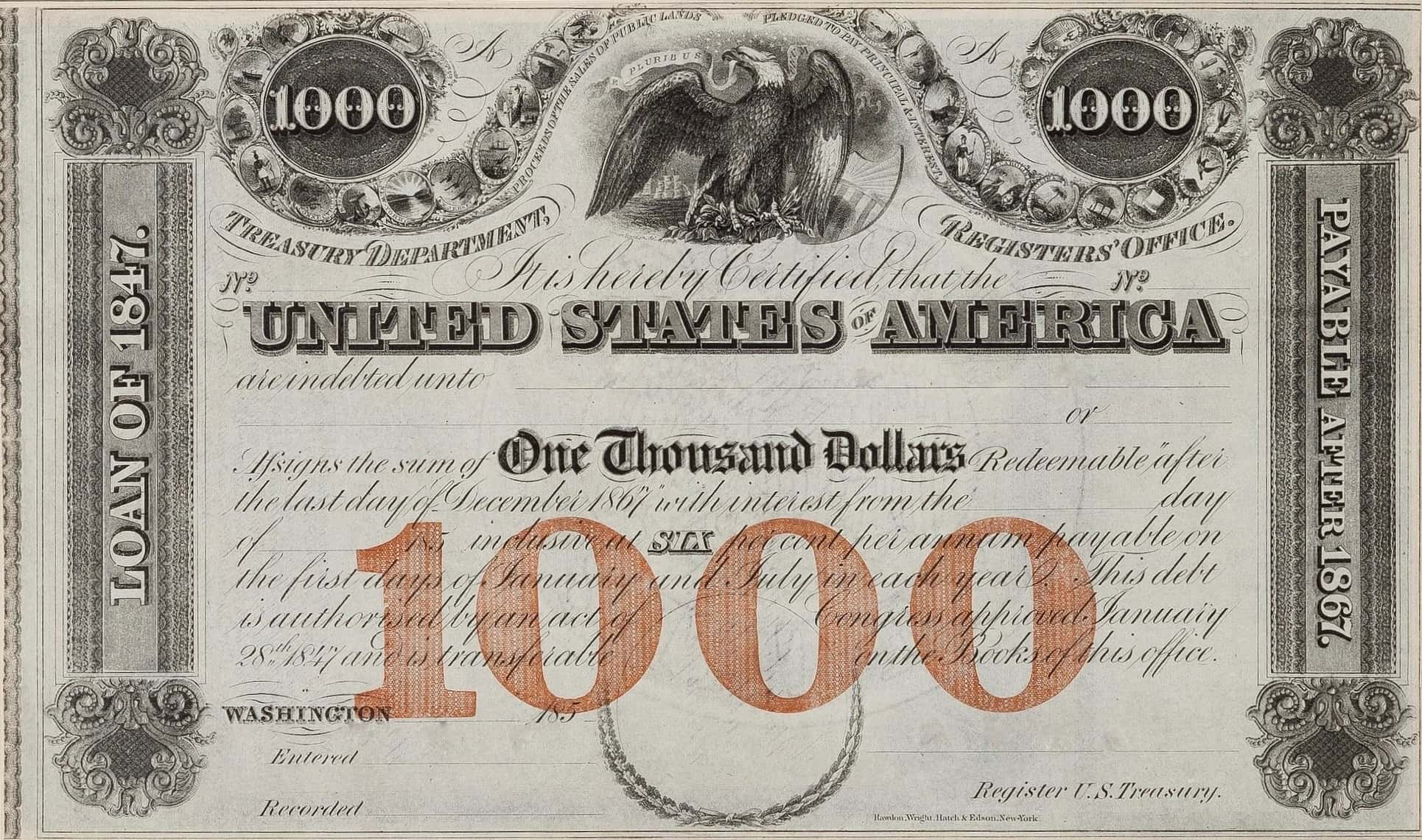

26. Let It Burn

Marie Curie won her Nobel prizes before the outbreak of World War I. In the wake, the now two-time Laureate offered to melt down her medals to fund the war effort. She put her prize money into war bonds after banks vetoed her dramatic gesture.

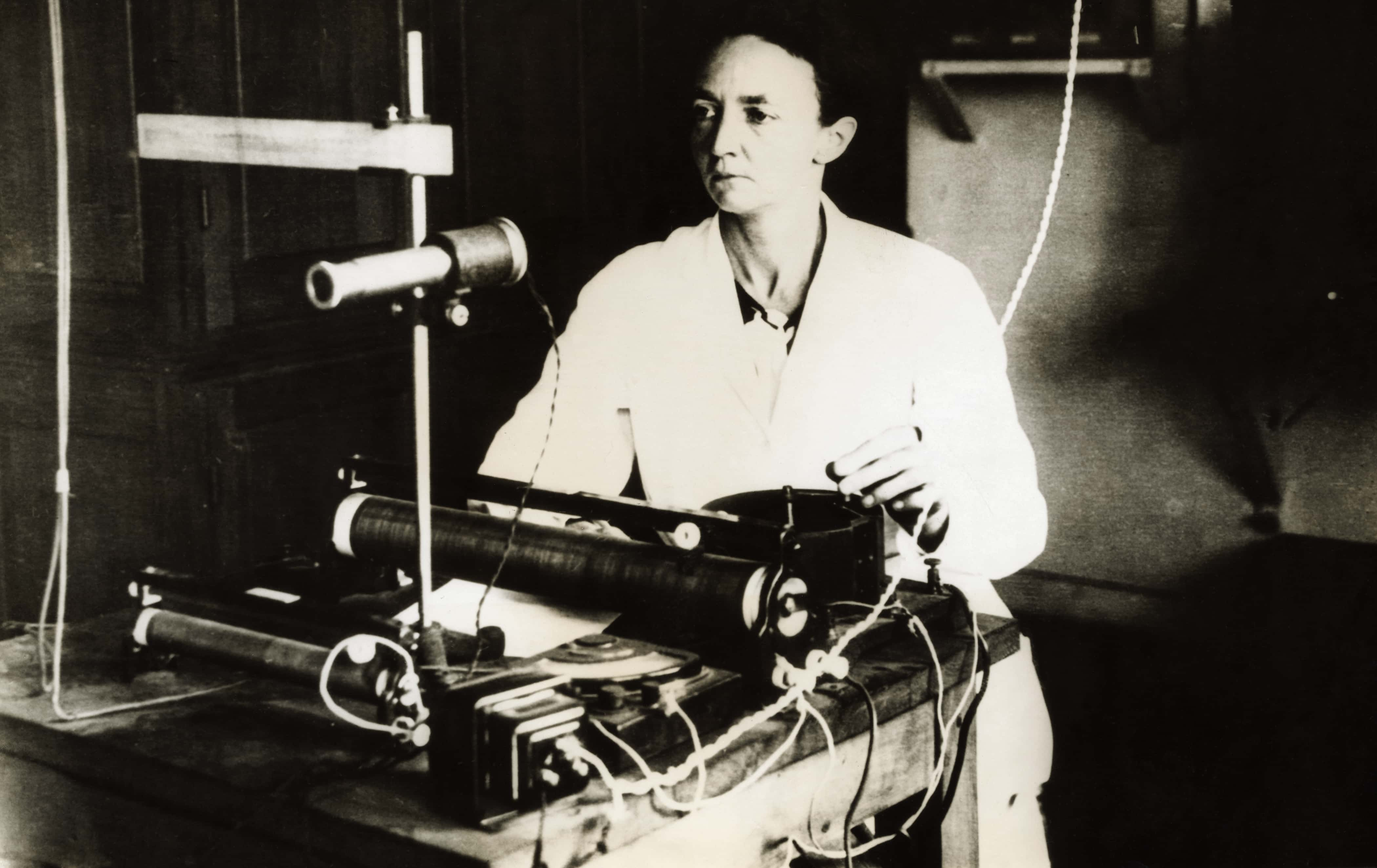

25. Travel-Sized Trauma

Marie invented mini X-ray machines to assist French soldiers during World War I. Not only did she create the technology, she also learned to drive and helped wounded men herself at the Battle of Marne. The small X-rays became known as “petite Curies.”

Wikipedia, vapaa tietosanakirja

Wikipedia, vapaa tietosanakirja

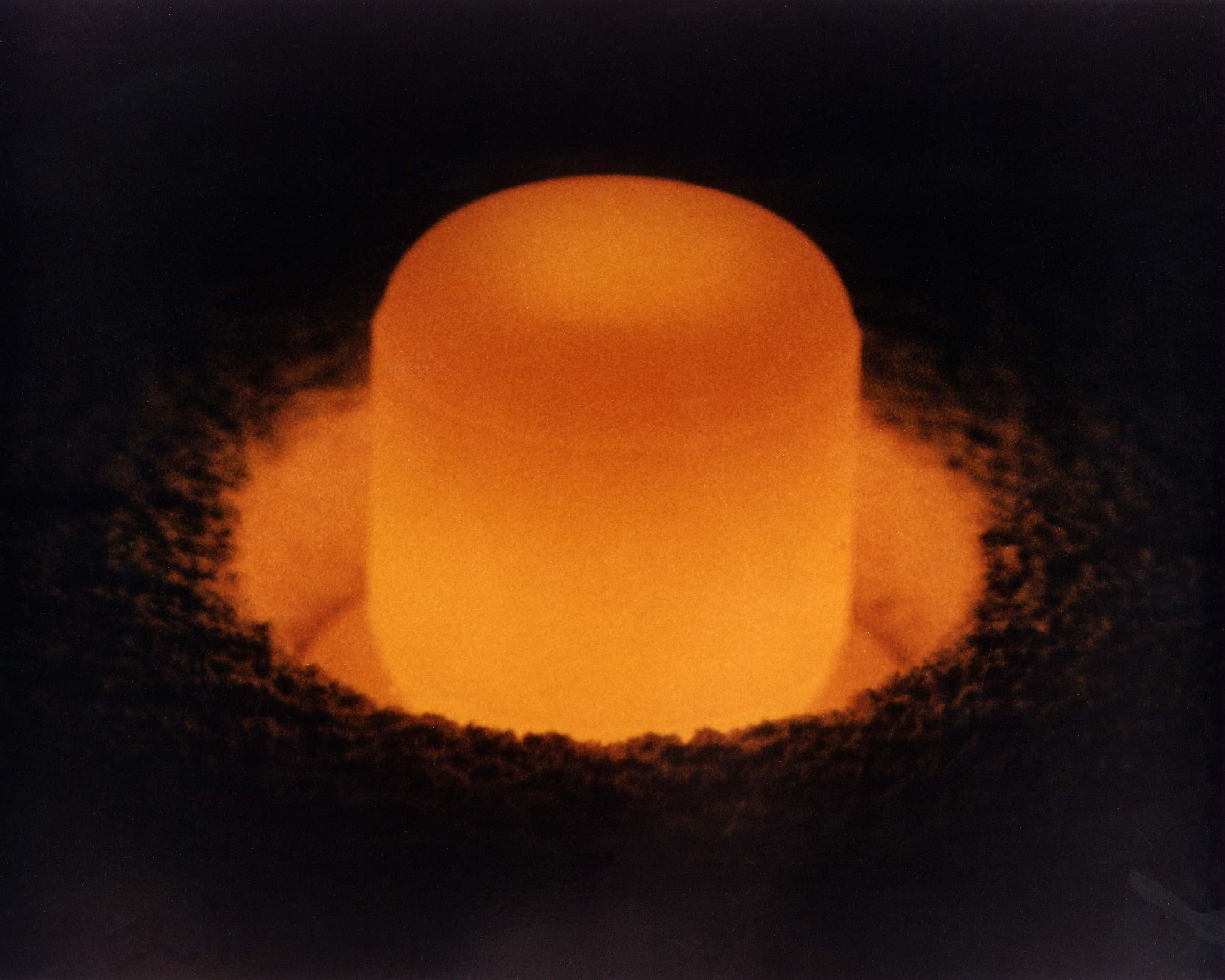

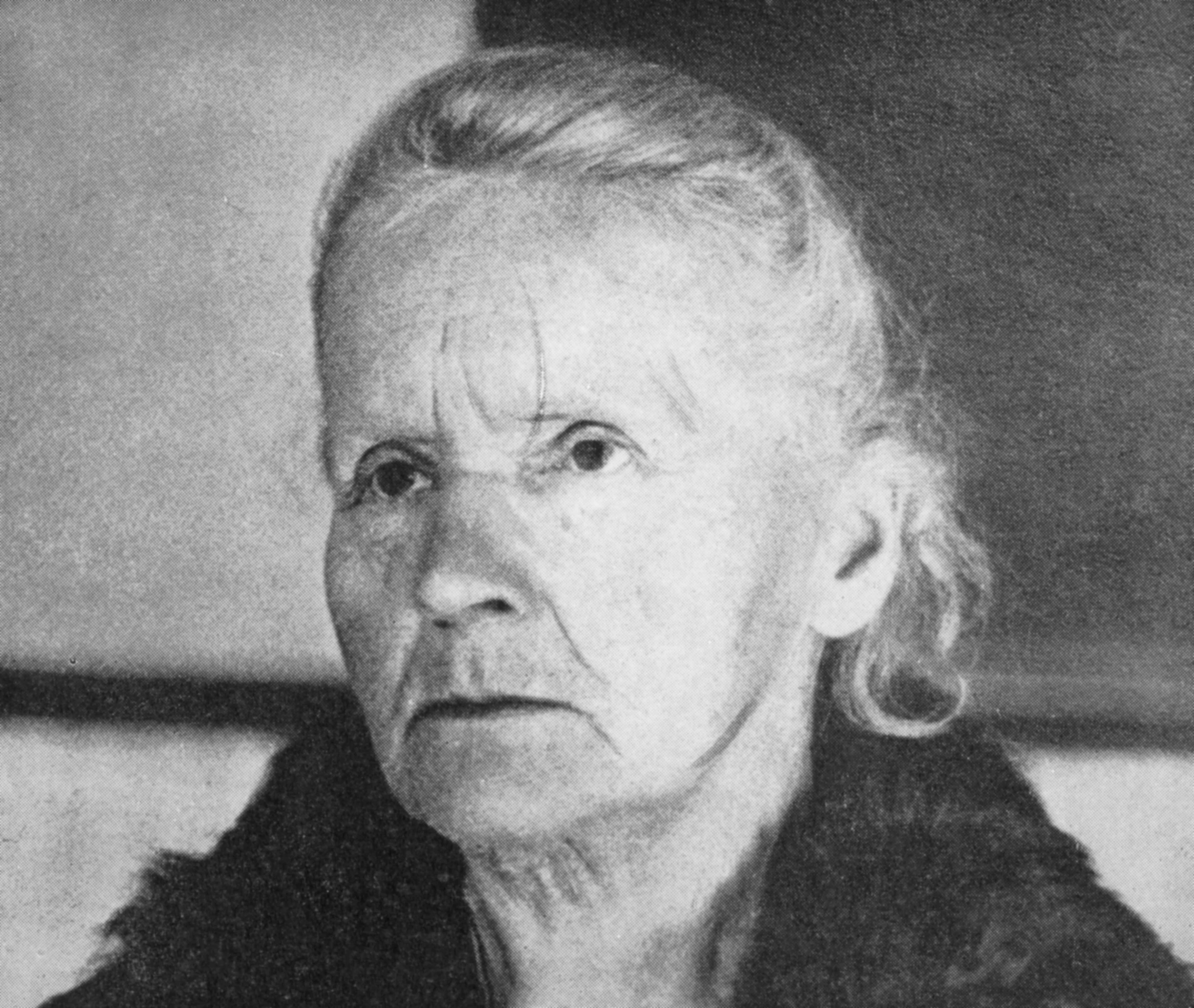

24. The Bitter End

Marie Curie died of aplastic anemia in 1934. The disease was almost definitely a result of her blasé comportment around radiation.

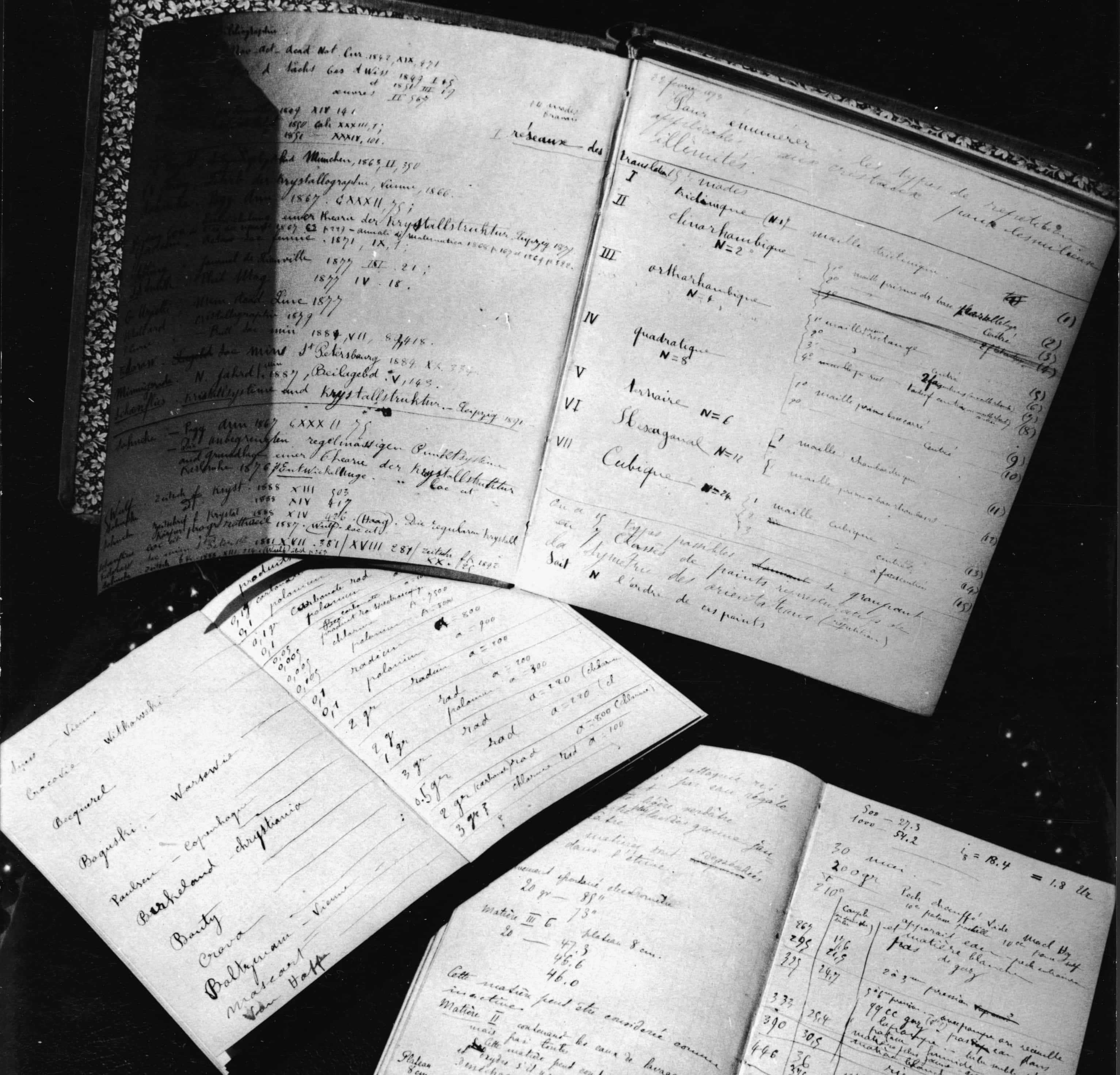

23. When Notetaking Is a Death Sport

The notebooks of Marie Curie remain too radioactive for human touch to this day. Stored in lead boxes for our safety, these notes will probably take another 1,500 years to become safe again.

22. Looking for New Tenants

In one of the tragic ironies of science history, Marie’s husband and research partner Pierre died before the University of Paris could complete their promise to build him a better lab. It was the shack for now…

21. Say My Name

It’s a long way from the lab to the Nobel Prize podium. Especially if you’re a woman in 1903. Case in point: Marie was almost not named at all by the Nobel Prize Nominating Committee. When the French Academy of Science nominated both Marie and Pierre Currie for the Nobel Prize, the board completely ignored the “Marie” part of their proposal and just listed Pierre’s name. Luckily, a member named Gösta Mittag-Leffler, a math professor from the Universiy College of Stockholm caught the glaring “mistake” and warned Pierre. Marie’s man stood by his wife and insisted that they be considered for the prize as a team.

20. The People’s Element

Marie Curie refused to make an intellectual property claim over the discovery of radium. Instead, she and Pierre made their research open to other scholars and producers. Even during the “Radium Boom” of the 1920s—when a single gram of radium cost $100,000—Marie had zero regrets about her open-access approach to science. In her words, “Radium is an element, it belongs to the people.”

19. Double Standards

In 1910 and 1911, Marie had an affair with Paul Langevin, a former student of her late husband. Unfortunately, Langevin was married (but estranged from his wife), so the media was quick to lambaste Marie as a homewrecker. Anti-Semitic tabloids preyed upon her Polish immigrant background to present her as a foreign Jewish temptress who destroyed a local family.

18. Don’t RVSP

In the fallout of her affair with Paul Langevin, Marie was discouraged from coming to Stockholm to accept her second Nobel Prize.

aliagadickensbeaconbaby.wordpress

aliagadickensbeaconbaby.wordpress

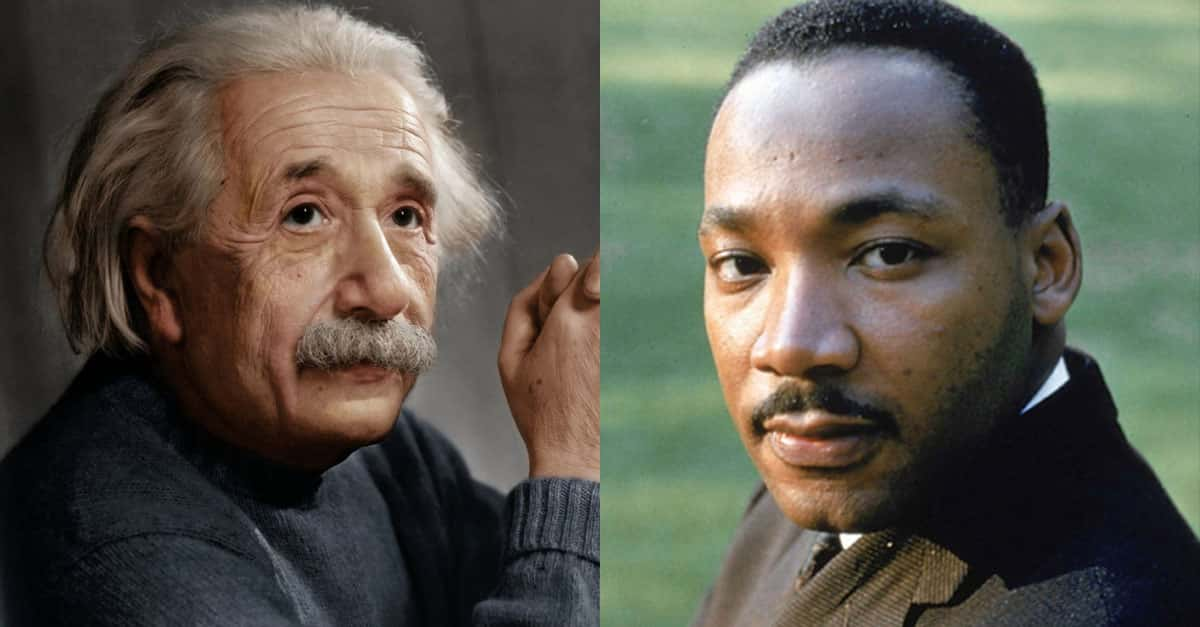

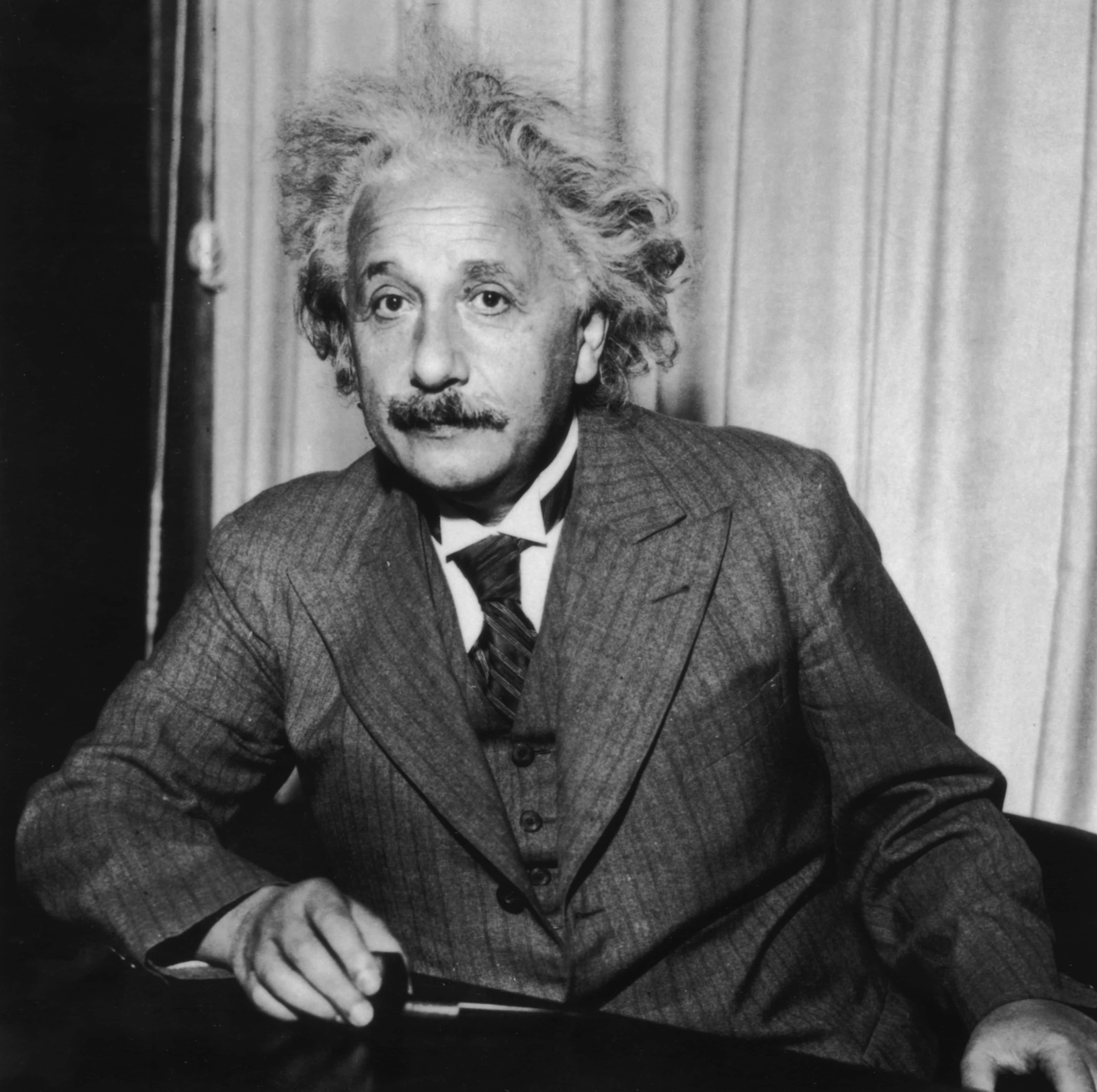

17. Thanks, Einstein

Albert Einstein wrote a letter of support to Marie Curie in the aftermath of her bedroom scandal. The female scientist was at her lowest emotional point when Einstein wrote to her in admiration of her achievements. He also offered some good PR advice, telling Curie “to simply not read that hogwash, but rather leave it to the reptile for whom it has been fabricated.” In other words, deny, deny, deny. But she appreciated it: Curie brushed off the scandal and accepted her second Nobel Prize in Stockholm.

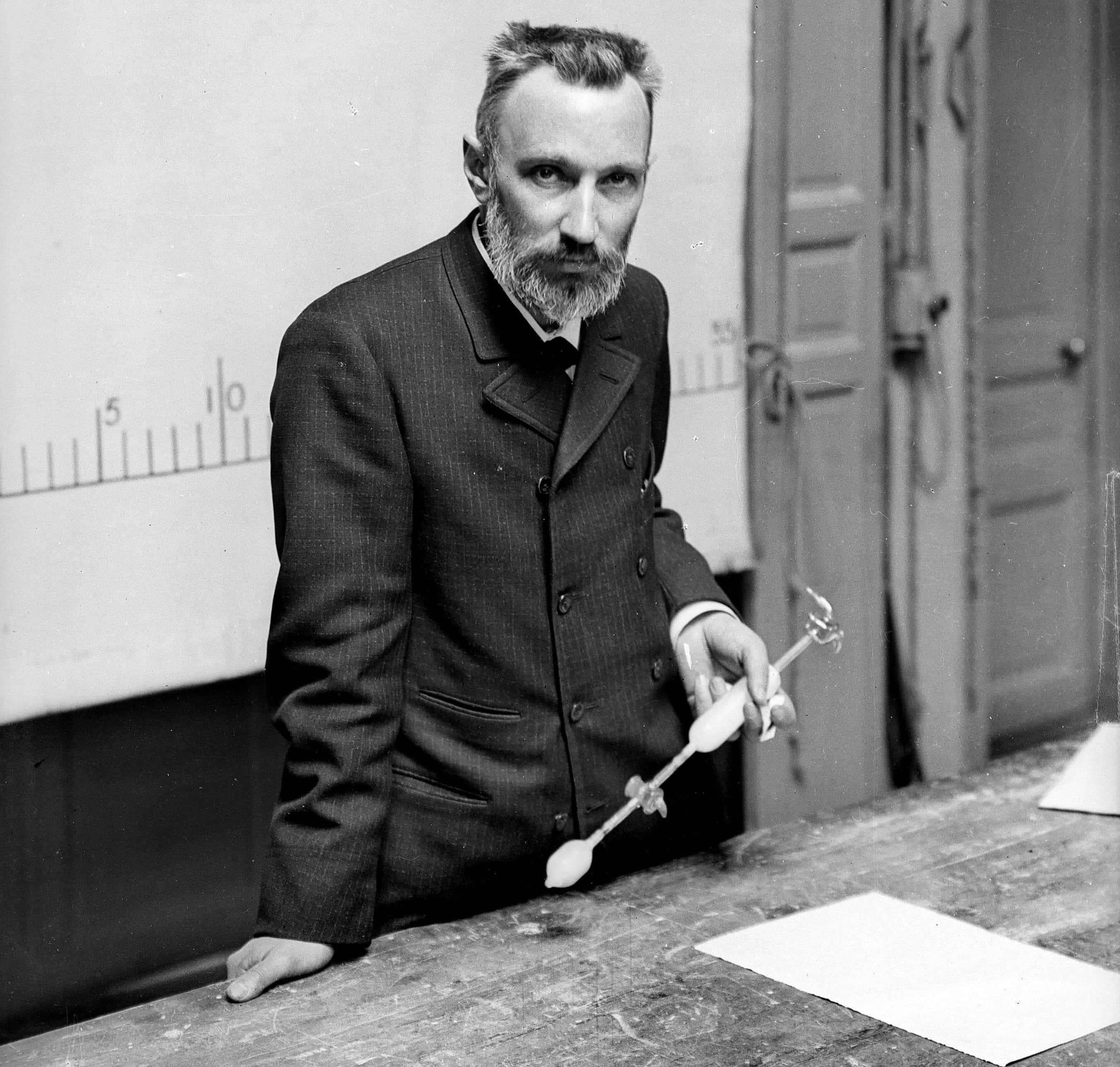

16. Love It and List It

Marie and Pierre Curie’s “meet cute” was the stuff of Hollywood rom-com. In the mid-1890s, the budding scientist Marie was on the look-out for a bigger lab. Her colleague, Professor Jozef Wierusz-Kowalski, referred Marie to Pierre, whom he thought would have what she needed. He didn’t have the lab space, but he did share a mutual attraction and love of science with Marie that resulted in romance.

15. Say Oui to the Ring?

Pierre had it bad for Marie. How bad? Well, Marie had plans to return to Poland after her studies. Pierre refused to part with her…even if that meant moving back with her and “reducing” himself to teaching French in her native country—his sentiment, not ours. In the end, a letter from Pierre was what convinced Marie to complete her PhD in Paris, where the prospects were slightly better for female scholars.

Public Domain Pictures

Public Domain Pictures

14. That’s Her Something Blue

Maria Sklodowska and Pierre Curie were married in a civil union in July 1895. Instead of a wedding dress, Marie wore a dark blue outfit, which would also be her lab uniform for the years to come. They loved science, so why not get married doing what you love?

13. Chop It Up to Atoms

Marie’s discovery that atoms were divisible would basically lead to the creation of atomic physics as we know it.

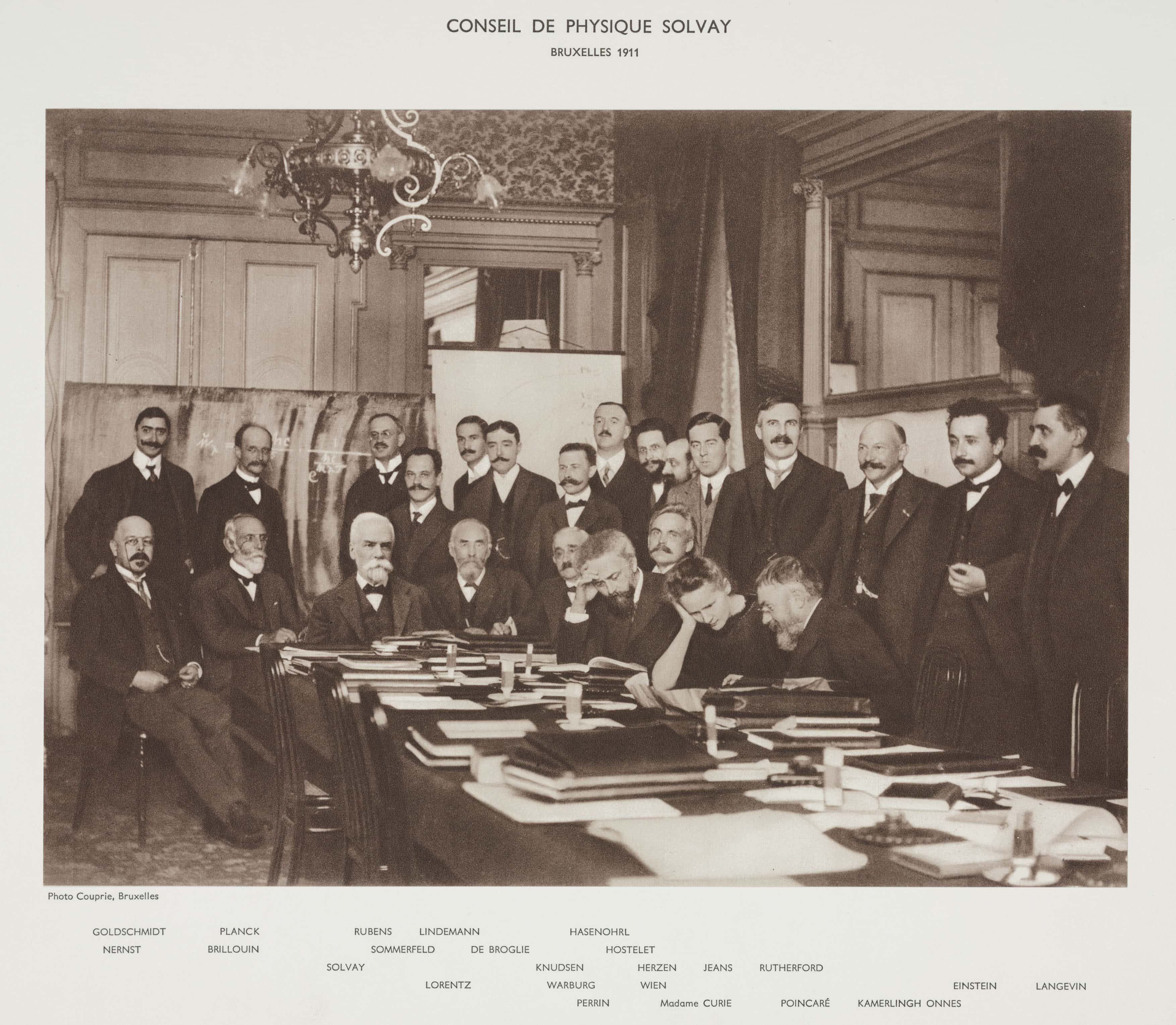

12. One Girl Policy

Even after two Nobel Prizes, Marie was the odd woman out. She was the only woman at the entire first Solvay Conference of 1911. It was invitation only.

11. Stunt Double

In 2014, the Republic of Togo was proud to release a stamp featuring the visage of Marie Curie. Unfortunately, what got printed was not a picture of Curie, but rather the actress Susan Marie Frontczak, who played Marie Curie. In Togo’s defense (kinda), Frontczak has made a living by playing Marie Curie on stage around the world for more than 13 years. She was not happy about her likeness being put on stamps from Mali, the Republic of Togo, Zambia, and the Republic of Guinea, at least without her permission.

10. The Crowd Has Spoken to Marie Curie

Before there was Patreon, there was Marie Curie. In 1920, she came into possession of a “crowd-sourced” radium when she needed more for her research. The public put two (and more) pennies together to ensure the legendary scientist got what she needed. More specifically, American women got together to support a fellow gal. The Marie Curie Fellowship began with this act of charity.

9. Ladies Helping Ladies

On her way to pick-up her crowdfunded gram of radium, Curie met US President Warren G. Harding. The head of state handed Marie the radium himself (we hope not literally…) and his wife Florence was also there. Florence was one of the women who spearheaded the crowdfunding effort to get Marie that good stuff.

8. Bad Timing

In 1929, Marie arrived in the US to pick up the cash for another gram of radium…just two days after the Great Depression kicked off with an iconic stock market crash. Yeah, it didn’t look great. Despite the optics, President Hebert Hoover took the time to present her with the bank draft right at the White House. She was sure to give Hoover a thank-you note.

7. Crush on You

Considering the way Marie Curie died, one would imagine her partner in science and love, Pierre, would have the same radioactive end. His demise was much quicker: on April 19, 1906—just three years after winning the Nobel Prize with Marie—Pierre was crossing a busy Parisian street when he tripped, fell, and was promptly crushed to death (headfirst) by the wheels of a horse cart. According to his father and an assistant, Pierre was usually somewhat absent-minded, which could have led to him carelessly stepping out into the street without looking.

6. In Our Bones (and Marrow)

Marie Curie’s daughter and son-in-law also died of radiation poisoning. After Nobel prizes, this seems to be the second thing that ran in their family.

5. Sweet Dreams?

At her bedside, Marie kept a vial of radium as her night light. That midnight reading better have been worth it…

4. International Lampoon’s Vacation

Albert Einstein and Marie Curie remained close friends for almost 25 years. In addition to attending those fancy smart people events, the pals just liked to have fun and take their families together for hikes on the Swiss Alps. I want to see that road trip movie.

3. Maybe In Another Life, Marie Curie…

Long after Marie Curie ended her affair with Paul Langevin—in fact, two generations after—her granddaughter and his grandson got married. For the record, the granddaughter, Hélène Langevin-Joliot, followed the family footsteps to become a nuclear physicist, just like her husband, Michel Langevin.

2. Pixie Dust and Poison

At the time of their investigations, Marie and Pierre Curie had no idea that radium could be so hazardous to human health—to be fair, they literally just discovered it… As a result, they were horrifyingly blasé about the substance. She would literally just walk around with bottles of radium in her pockets. At night, the couple would release the day’s tension by visiting their workroom and basking in the whimsical glow of their lab. As it was described in Marie’s autobiography, “all sides the feebly luminous silhouettes of the bottles of capsules containing our products […] The glowing tubes looked like faint, fairy lights." What a romantic way to get lymphoma.

1. Nerd Love

In her youth, Marie became star-crossed lovers with the future acclaimed mathematician, Kazimierz Zorawski. At the time, Marie was working as a governess in his parents’ household. While they talked of marriage, she was too poor to be a good prospect for his family, and the affair was ended. The separation was mutually painful. Even after Zorawski became an esteemed professor at Warsaw Polytechnic, Marie’s now-elderly sweetheart would seat himself in front of her statue at the Radium Institution and stare at it wistfully.