In the early 20th century, no man was as infamous as William Randolph Hearst. The tycoon gobbled up newspapers and splashed starlets and scandals all over his headlines—but nothing compared to his own dark bedroom secrets. From illicit mistresses to an unsolved mystery, here are 43 facts about William Randolph Hearst.

1. Golden Boy

Some tycoons are born into poverty and claw their way up the ladder—but not William Randolph Hearst. Born in 1863, he was the son of the millionaire engineer George Hearst and his, ahem, much younger wife Phoebe Apperson Hearst. Baby William had more than just a silver spoon in his mouth: his father mined gold.

2. Citizen Will

These days, many people’s knowledge about William Randolph Hearst comes from Orson Welles’ classic film Citizen Kane, which is loosely (and very notoriously) based on his life. But while Citizen Kane has gone down in movie history for showcasing some of Hearst’s bizarre acts, his real life was even darker and stranger.

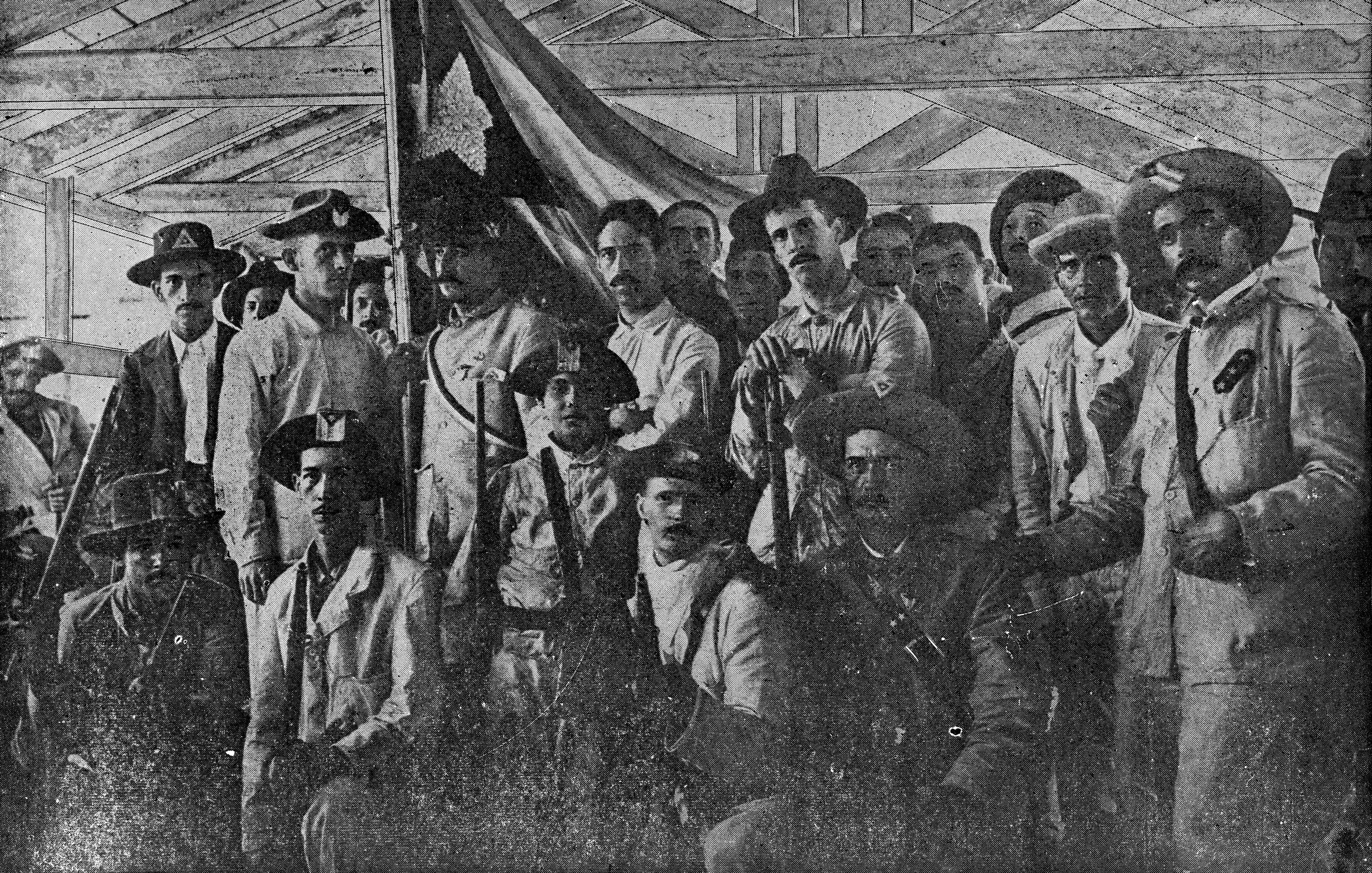

3. Pics Please

According to one legend, Hearst wasn’t above war-mongering to get his way. When the Cuban War of Independence happened in the late 19th-century, Hearst sent illustrator Frederic Remington to cover the events. When Remington later cabled his boss and said that nothing much was happening on the front, Hearst’s response was utterly chilling.

"Please remain.” He allegedly said, “You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war.”

4. School Daze

Like any good little rich boy, Hearst enjoyed the best education money could buy as he was growing up. He not only attended the prestigious St. Paul’s prep school in New Hampshire, he also got into Harvard University in the class of 1885. Whether that was on his own merits or his daddy’s money is up for debate…

5. Losing out

Hearst had dreams of becoming a politician, possibly even a president. Sadly, most of his attempts ended in heartache. Though he was elected to the House of Representatives a handful of times, he always seemed to lose out when it came to bigger elections, earning him the sneering nickname William “Also-Randolph” Hearst.

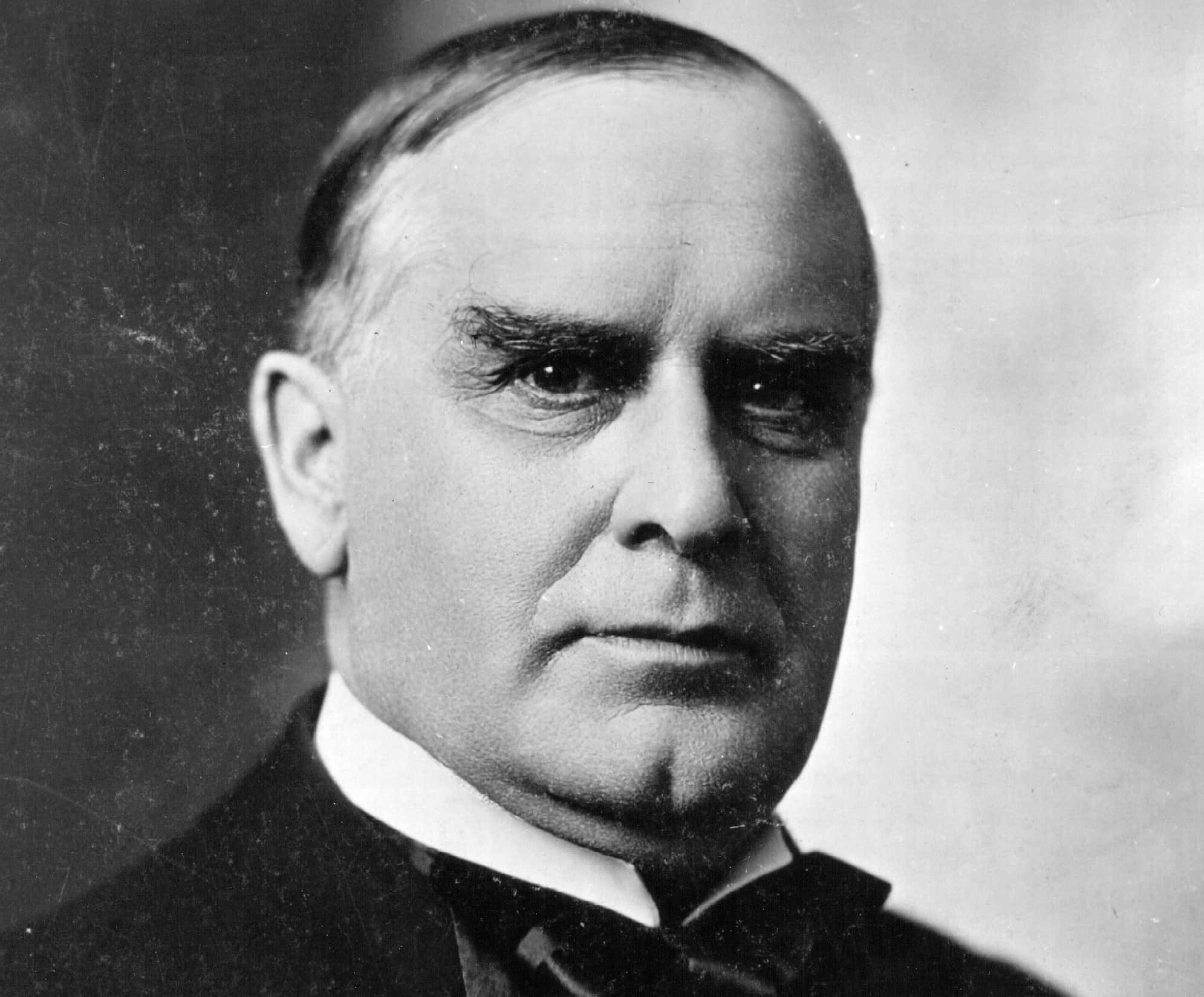

6. Bait and Switch

Perhaps letting off steam from his failed political ambitions, Hearst frequently criticized the American president William McKinley in his papers, and even printed a poem by Ambrose Bierce that talked jokingly about assassinating him. Then in 1901, the unthinkable happened: an anarchist actually did assassinate President McKinley.

Though he denied any involvement, many in the media blamed Hearst for the violent tragedy.

7. Broadway Baby

Around 1897, Hearst became smitten with the alluring chorus girl Millicent Veronica Wilson after seeing her star in the Broadway show The Girls From Paris. At the time, she was only a 16-year-old ingénue, while Hearst was a full-grown 34-year-old man. Millicent’s sister Anita had to chaperone their first dates together.

8. The Six-Year Itch

The young and nubile Millicent was also very politically well connected through her mother’s side, making her all the more of a catch for the ambitious and power-hungry Hearst. After waiting six years—until Millicent was a more appropriately aged 20-year-old—the two tied the knot in a respectable ceremony in 1903.

9. Animal House

While attending Harvard, Hearst made a name for himself for all the wrong reasons. He was a well-known hellion on campus, and often sponsored all-night ragers and beer parties—but that was just a small fraction of his debauched antics. His signature move was to defecate in pudding pots and then send them to his professors at school. Aw, what a nice memento.

10. The Old College Try

After terrorizing Harvard for almost two years, the administration finally gave Hearst what was coming to him: They expelled him in 1887. Karma’s a witch, Will.

11. The Other Woman

Around 1918, Millicent and Hearst’s marriage started falling apart—for a very scandalous reason. Hearst had begun producing movies in Hollywood, which is where he met and became besotted with the glamorous actress Marion Davies. Within a matter of months, he had moved Davies into a secret love nest in Manhattan so he could visit her away from prying eyes.

12. Green-Eyed Monster

Hearst was an incredibly jealous man, and his mania extended far into his relationship with Davies. When she starred in high-profile vehicles, he would reportedly even demand that directors cast her opposite men who were either gay or middle-aged—ensuring that she didn't accidentally fall in love with a heartthrob on set.

13. The Family Business

In 1887, Hearst started working for the San Francisco Examiner—after all, his father George owned and controlled the publication. But if George thought his son was going to follow in his footsteps, he was dead wrong. The younger Hearst’s first change was to adopt the lofty slogan “the Monarch of the Dailies” for the paper.

14. The Prodigal Son

Hearst then dealt his father an absolutely cold-hearted betrayal. Not only did the paper get a complete makeover, with Hearst upgrading all the equipment and writing talent, he also started publically attacking his father’s other companies in the newspaper, accusing them (probably rightly, let’s be honest) of corruption.

Wikimedia Commons, B. M. Clinedinst

Wikimedia Commons, B. M. Clinedinst

15. Hearst and Sons

Macho genes seemed to run in the Hearst family: he and Millicent had five children together, all boys.

16. Boss of the Month

At the beginning of his career, Hearst was known as an attractive and fair employer who was polite, “impeccably calm,” and happy to give his writers the credit they deserved. Of course, his reputation quickly changed…

17. The Uncrowned King

In 1919, Hearst started building his never-completed piece-de-resistance in California: Hearst Castle. The mack daddy of mansions, the not-so-humble abode became Hearst and Davies’ pleasure palace, and they hosted Hollywood heavy hitters like Charlie Chaplin and Greta Garbo within its lavishly decorated walls.

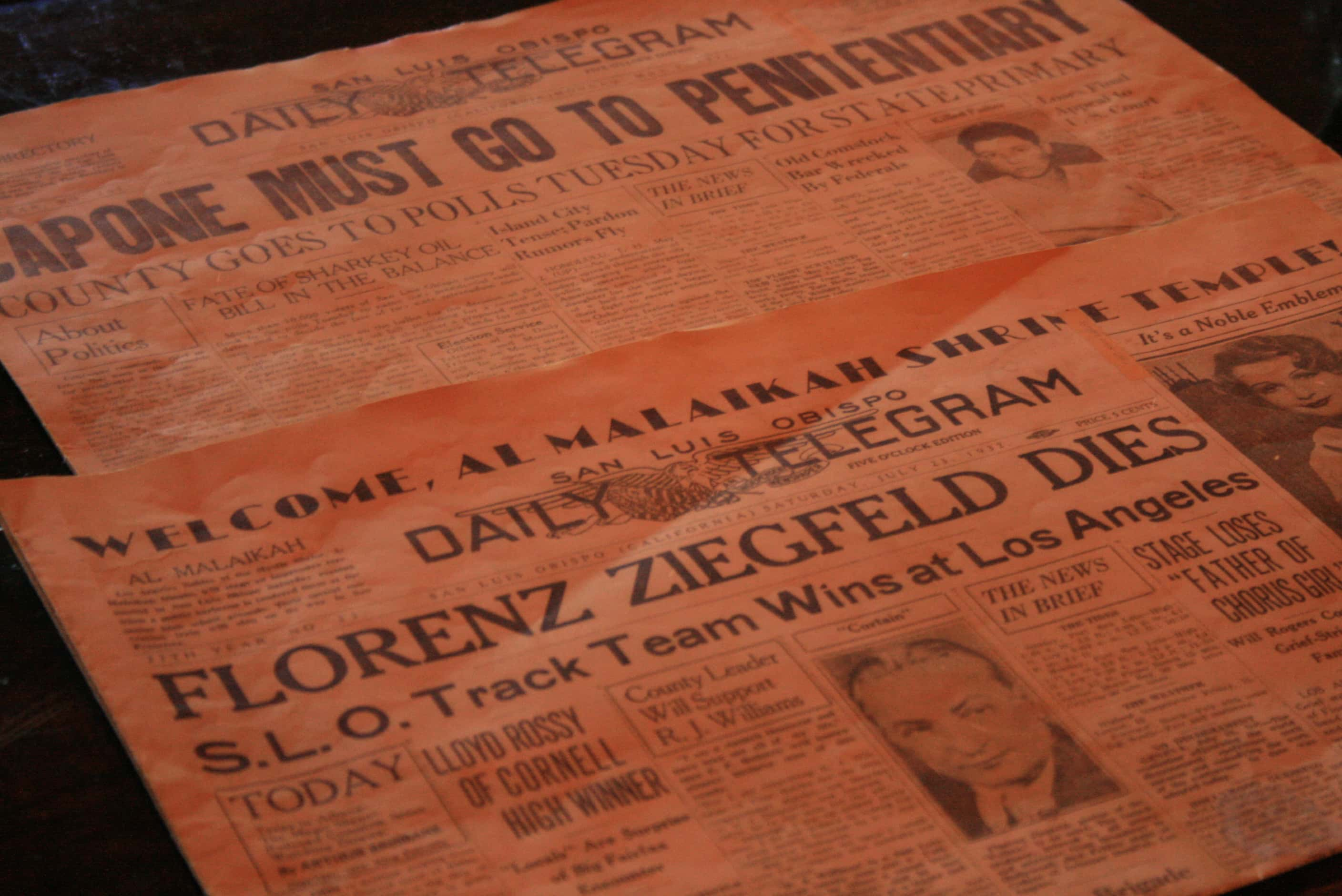

18. Yellow-Bellied

Along with Joseph Pulitzer's New York World, Hearst pioneered “yellow journalism,” what we now might call tabloid journalism. His headlines were always huge and sensational, and his papers focused on salacious crimes, human-interest stories, and colorful comics. While some readers ate it up, critics were angry that the rags peddled misinformation, if not outright lies.

19. Shut It Down

When Hearst got word that the film Citizen Kane was using his likeness, he was absolutely furious—and he went to deranged lengths to keep the movie from the public. He tried to leverage his enormously powerful connections to ban the film from being released, but he was ultimately unsuccessful and was left to fume impotently as it became a bonafide hit.

20. Talent Scout

Hearst rose very quickly and ruthlessly through the newspaper world, unafraid to make enemies and do whatever it took to gain power. And it took a lot. He stole star talent like Richard F. Outcault from rival publications and even once ripped the entire Sunday staff away from the New York World newspaper, his main competitor.

21. Glow up

There was almost no part of Marion Davies’ career that Hearst didn’t meddle in. He relentlessly advertised Davies across all of his publications, and even employed the gossip journalist Louella Parsons to praise her almost constantly, often with the widely ridiculed catchphrase "Marion never looked lovelier."

22. Dear Diary

Any time someone crossed Hearst, he made sure they felt his wrath in the most brutal way possible. He would take to his newspapers and use them as weapons against his enemies, writing bitter and rambling editorials about his foes in all capital letters.

23. Mogul Mania

At its height, Hearst’s newspaper company was the largest media conglomerate in America.

24. A Castle for His Queen

When the playwright George Bernard Shaw saw St. Donat’s Castle in Wales, Hearst’s latest party pad, he quipped, "This is what God would have built if he had had the money."

25. An Affair to Remember

Eventually, Hearst and Davies’ long-term affair became common knowledge. Insiders even dubbed it the “worst kept secret in Hollywood.”

26. Your Name in Lights

In one of Hearst's more ridiculous moments, he purchased the Cameo Theatre in San Francisco, remodeled it, and then named it "The Marion Davies Theatre." The cinema was just down the street from his offices, and if he looked out of his window, he could see the neon letters spelling out his mistress’s name at all hours of the day.

27. What Goes up….

By 1928, Hearst was on top of the world. He owned a media conglomerate of tabloids, cartoons, and somewhat proper papers, all fueled by the abundant Hearst family fund. But tragedy was about to strike. In 1929, America plunged into the devastating Great Depression, and Hearst lost an immense sum of his fortune and papers.

28. No Laughing Matter

To top off all his controlling behavior, at the height of Davies’ film career, Hearst often tried to ban her from performing in comedies. He thought the genre was beneath her acting talents—despite the fact that she had a natural vivacity and comedic timing—and instead steered her toward more serious, dramatic projects.

29. Working Guy

After his great fall, Hearst was forced to work as a mere employee with a supervisor. It was a harsh comedown for a man who once ruled New York.

30. Doomed Descendants

Years after William Randolph Hearst’s death, the name “Hearst” became infamous once more when his granddaughter Patty Hearst was kidnapped and then brainwashed by the Symbionese Liberation Army in 1974. 19 months after her abduction, Patty turned from a mere victim into a fugitive when she took part (under duress, allegedly) in many of the group's violent criminal activities.

She was eventually arrested by police and controversially put in jail, though President Jimmy Carty later commuted her sentence.

31. Stand by Your Man

One of William Randolph Hearst’s only saving graces after his downfall was Marion Davies. When he was in dire financial straits, Davies still kept by his side and even sacrificed herself for her lover. She sold off much of her jewelry, stocks, and bonds, and wrote Hearst a million-dollar check to keep him afloat.

32. In It for the Money

By the 1920s, Millicent was thoroughly fed up with Hearst’s cheating ways, and she all but separated from him, living an independent life in New York City while Hearst spent most of his time on the West coast. Hearst even considered divorcing Millicent and making it official with Davies—but his bitter, estranged wife’s separation demands were too high.

33. Don’t Call It a Comeback

Hearst sold off much of his valuables and narrowly avoided bankruptcy in the Great Depression, but his name was all but mud in Hollywood after his financial misfortunes. Nonetheless, ever stubborn and unwilling to admit defeat, Hearst continued publishing on a smaller scale, and even saw a mild comeback during World War II.

34. Till Death Do Us Part

Despite Hearst’s 30-year affair with Davies, he and Millicent remained married until his death.

35. Kiss and Tell

Though many never understood Davies' attraction to the possessive, controlling Hearst, she explained her reasons to Charlie Chaplin's wife one night. "God, I'd give everything I have to marry that silly old man," she once said—though not just because Hearst gave her wealth and stability. As Davies confessed, it was because "He gives me the feeling I'm worth something to him."

36. All Downhill From Here

In 1947, Hearst was well into his 80s—and feeling his age. He left his now-reclusive existence in the remote Hearst Castle to live closer to medical facilities and hospitals. Yet, despite this attempt at a healthier life, his end was near and inevitable. The newspaper tycoon died in 1951, living until he was 88 years old.

37. Cold-Blooded

There are still a lot of dark rumors afloat about the final days of William Randolph Hearst. According to one source, Davies had very little understanding of what went on in his last moments. His house was crowded with people, noise, and chaos as everyone tried to say their last goodbye, and Davies got so upset that she was given a sedative.

When she woke up, her relatives had to inform her that Hearst had already died.

38. No-Show

As the illicit "other woman," Davies was even banned from attending Hearst's funeral.

39. Family Secret

Throughout his relationship with Davies, Hearst frequently spent time with her niece Patricia Lake—but Lake was hiding a dark secret. Just 10 hours before she died in 1993 of lung cancer, Lake made a shocking deathbed confession. She was actually Hearst and Davies’ illegitimate love child. She had kept the secret all through her life, even after the deaths of both her parents, and only ever told close family and friends.

40. Absent Parents

According to Lake, Davies told her of her true parentage when the girl was 11 years old. Hearst confirmed it much later, when she was 17 years old and he was about to walk her down the aisle to get married.

41. Tender Buttons

In Citizen Kane's famous ending, we finally see that Kane's darling "Rosebud" is actually a childhood sled. However, the real meaning of "Rosebud" may be much more scandalous. Writer Gore Vidal, who knew Marion Davies, claimed that "Rosebud" was what Hearst lovingly called Davies', er, private regions.

Citizen Kane (1941), RKO Radio Pictures

Citizen Kane (1941), RKO Radio Pictures

42. Lovers’ Quarrel

Scandal followed Davies and Hearst around throughout their entire relationship, but one of the most infamous events was the mysterious death of producer Thomas Ince in 1924 while he was aboard Hearst's luxury yacht. Rumors swirled that Hearst had shot Ince in a jealous rage after mistaking him for Charlie Chaplin, who he supposedly had seen seducing his mistress on the ship.

43. Nothing to See Here

Ince’s sudden, untimely death and the rumors surrounding it make for a very juicy story, but the truth is equally strange. Ince suffered from intense indigestion on the ship after drinking liquor, left the boat, and then died in his home of a vague heart condition. However, the sketchiness of the timeline and details mean that, murder or not, we may never know just what really happened that day.