The Path Of A Master

Albrecht Dürer was one of the greatest artists of the Renaissance era. Though he created paintings of unfathomable depth and detail, he is best known for his intricate and expressive engravings. Dürer mass-produced prints of these engravings, which found their way all around Europe, spreading his name across the continent. The world of art would never be the same.

Early Life in Nuremberg

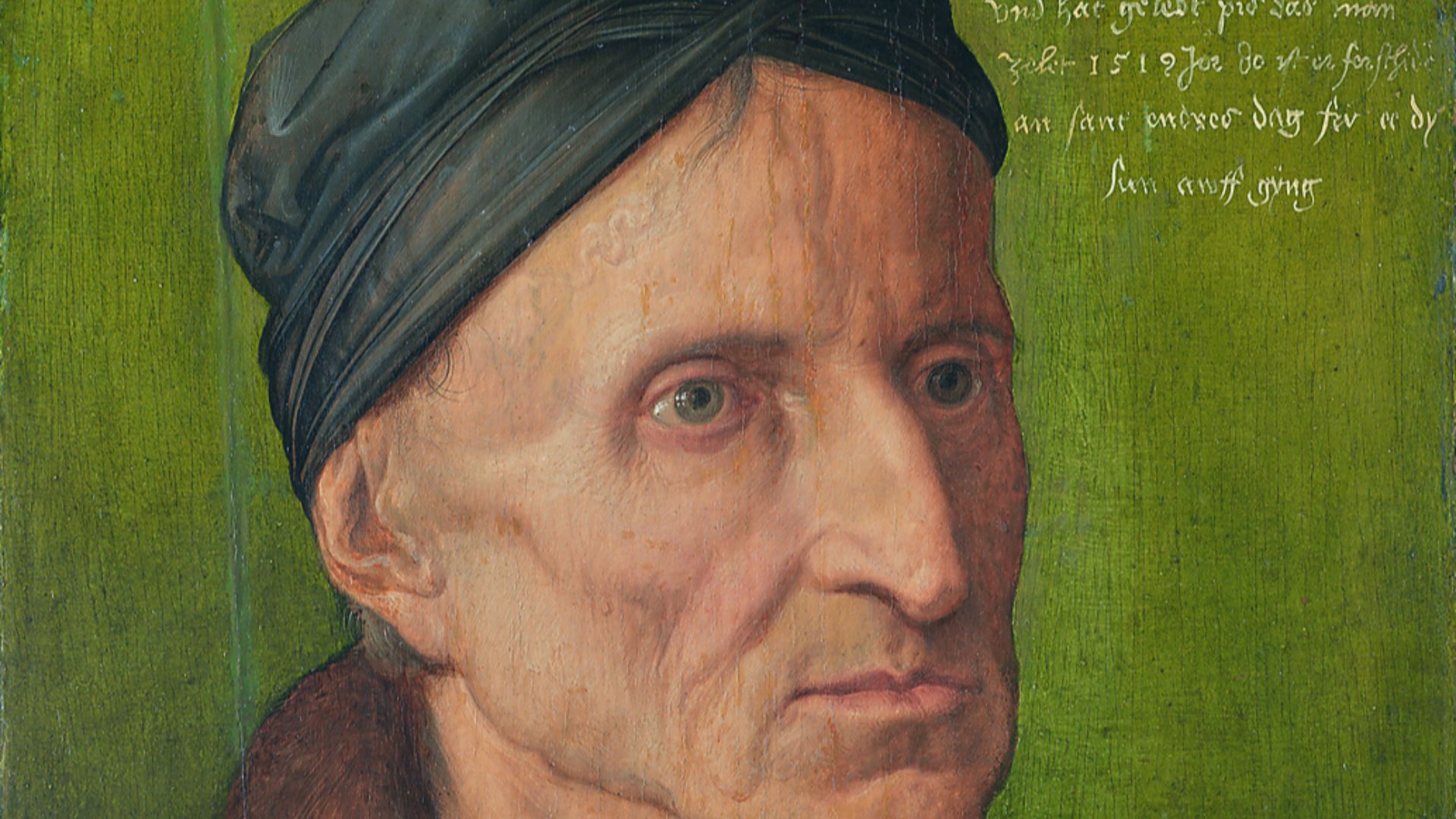

Albrecht Dürer was born in 1471 in Nuremberg, a thriving hub of trade and craftsmanship. Raised in a family of goldsmiths, he learned the value of careful precision from an early age under the tutelage of his father and local masters. Mistakes and sloppy work were not tolerated lightly. His early drawings and experiments revealed his remarkable eye for detail, a long time before he ever trained formally in those arts.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Training Under Michael Wolgemut

Dürer apprenticed with Michael Wolgemut, a major figure in German printmaking. Here he learned the foundations of book illustration and the expressive potential of woodcut images. The workshop exposed him to large projects, technical discipline, and the commercial side of art.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

A Young Artist on the Move

After finishing his apprenticeship, Dürer traveled across Europe to expand his artistic education. His journeys to the Low Countries, the Rhine region, and beyond brought him into contact with new artistic styles, inspiring his early experimentation with landscape and portrait studies. He was determined to make maximum use of everything he'd learned.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Marriage to Agnes Frey

In 1494, Dürer married Agnes Frey, a union arranged between two respected Nuremberg families. Although not known for affection, the partnership stabilized his finances. Agnes later helped sell and distribute his prints throughout Europe, turning Dürer’s art into a viable business enterprise.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

First Journey to Italy

Shortly after marrying, Dürer traveled to Italy, where he encountered classical proportions, mathematical perspective, and Renaissance humanism. Studying Venetian artists such as Giovanni Bellini expanded his understanding of light, anatomy, and balance, ideas that profoundly reshaped his whole approach to art.

Giovanni Bellini, Wikimedia Commons

Giovanni Bellini, Wikimedia Commons

Return to Nuremberg

Dürer returned from Italy eager to apply what he had learned. His workshop quickly became known for its meticulous craftsmanship and daring ideas. He blended Northern detail with Italian proportion, producing works that broke from Gothic tradition and introduced Renaissance ideals to German art.

Yair-haklai, Wikimedia Commons

Yair-haklai, Wikimedia Commons

Master of Woodcut

Dürer revolutionized woodcut printmaking by introducing complex shading, dramatic contrast, and finer linework. Working closely with expert block cutters, he elevated the medium from simple illustration to high art, demonstrating that prints could rival paintings in emotional and visual impact.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Master of Engraving

His engravings revealed an unmatched command of the burin, the tool that scored the material, which in Durer’s case was most often copper. Through layered cross-hatching, controlled pressure, and intricate textures, Dürer achieved a level of depth, atmosphere, and precision that set a new standard in European printmaking for generations.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

The Apocalypse Series

Dürer’s 1498 ‘Apocalypse’ woodcuts stunned Europe with their bold lines and apocalyptic imagery. The series, especially ‘The Four Horsemen,’ showcased his ability to combine biblical intensity with technical finesse, earning him international fame.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Rising Fame and Patronage

As his reputation grew, Dürer attracted wealthy patrons and expanded his workshop’s output. His prints circulated widely—far beyond the reach of paintings—helping establish him as one of the first artists to achieve a pan‑European reputation during the Renaissance.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Travel and Observation

Dürer’s travels through German and Alpine regions inspired some of the earliest naturalistic landscape studies in European art. His observational drawings demonstrated a scientific curiosity that influenced later traditions of topographical and botanical illustration.

Superikonoskop, Wikimedia Commons

Superikonoskop, Wikimedia Commons

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1498)

From the groundbreaking Apocalypse woodcuts, this dramatic scene shows the biblical horsemen sweeping across the page with violent force. Bold imagery and expressive linework established Dürer as a visionary printmaker who could weave a story while also exhibiting technical mastery.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

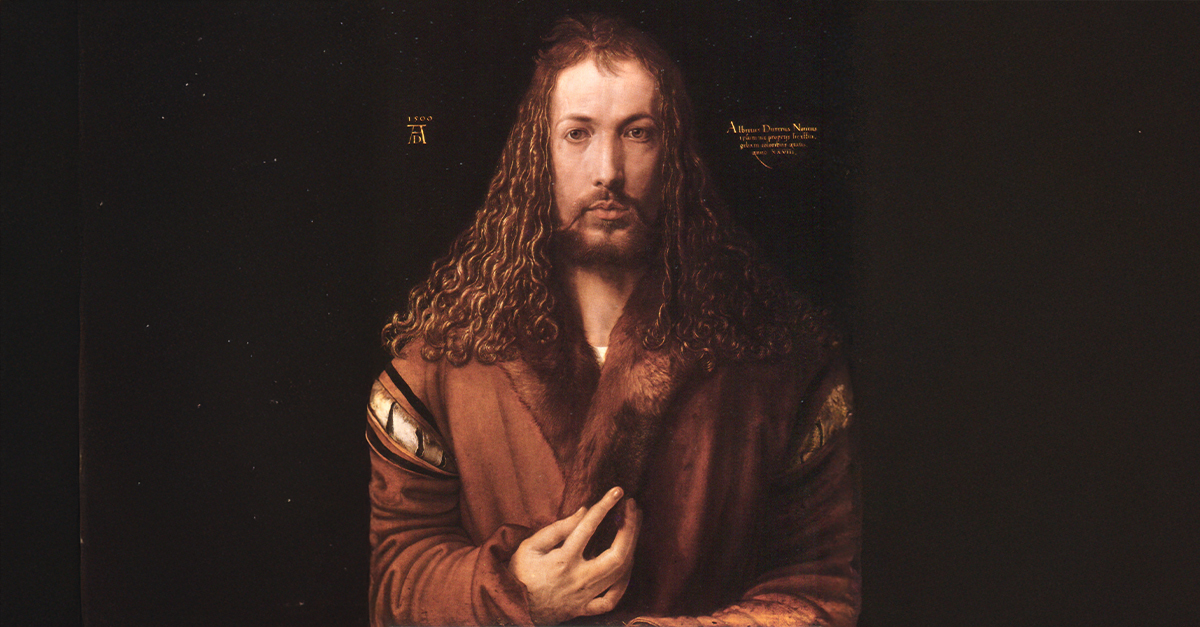

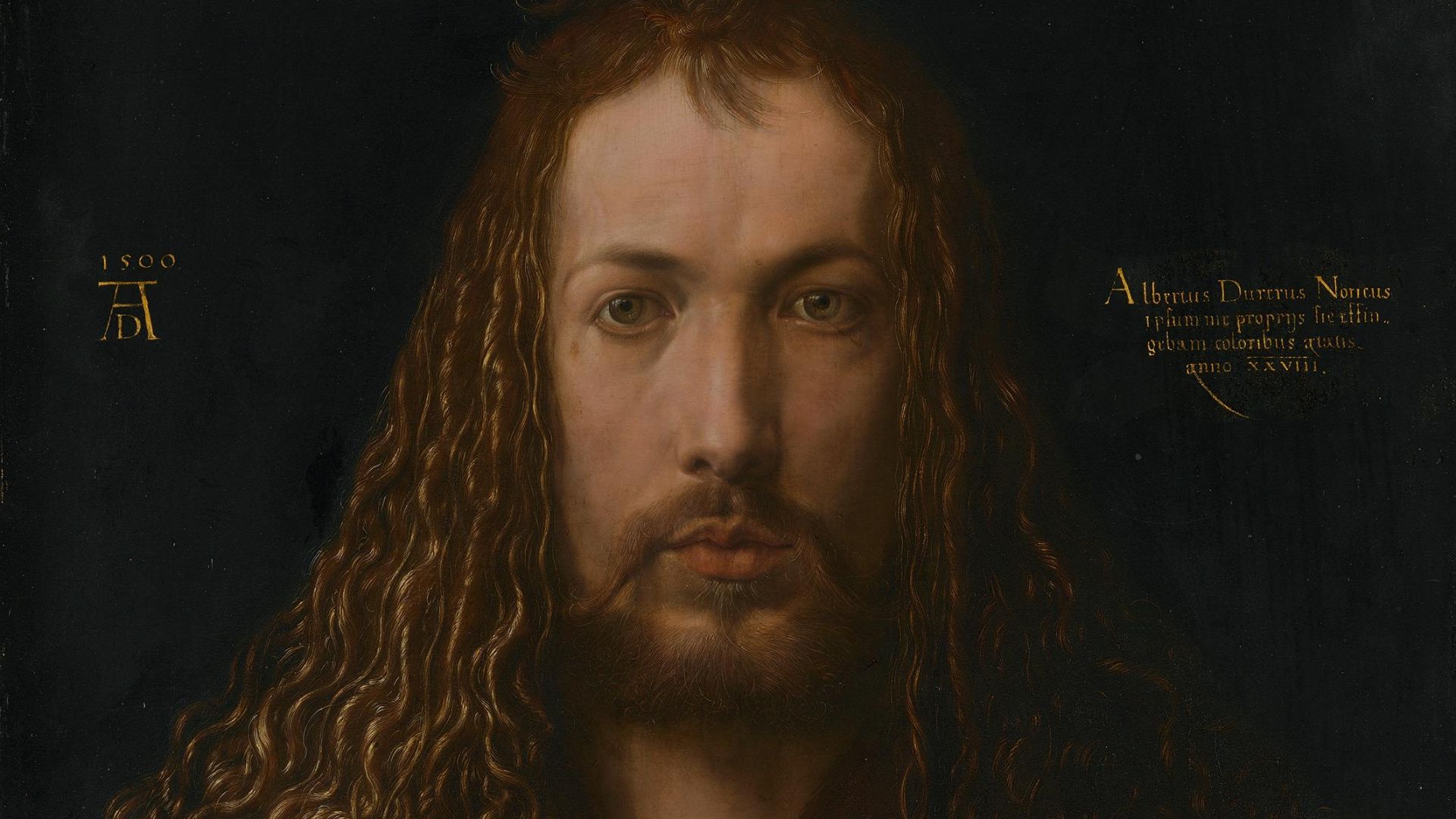

Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight (1500)

Dürer’s self‑portraits reveal a confident and introspective artist shaping his public identity. The famous 1500 painting presents Dürer in a rather serious-looking, frontal pose that alludes to sacred imagery. By using this format, he asserted the elevated identity of the artist, revealing his deep belief in the growing power of art during the Renaissance.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Young Hare (1502)

This iconic watercolor displays Dürer’s extraordinary ability to render texture, light, and lifelike detail. The rabbit’s fur, alert posture, and gleaming eye show his precision and sensitivity. The work remains one of the most admired natural studies of the Renaissance.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

The Great Piece of Turf (1503)

This watercolor transforms ordinary weeds into a detailed scientific study. Its realism, subtle lighting, and patient observation revealed Dürer’s belief that even the smallest corner of nature deserved artistic attention. The work helped establish naturalism as a respected artistic pursuit.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

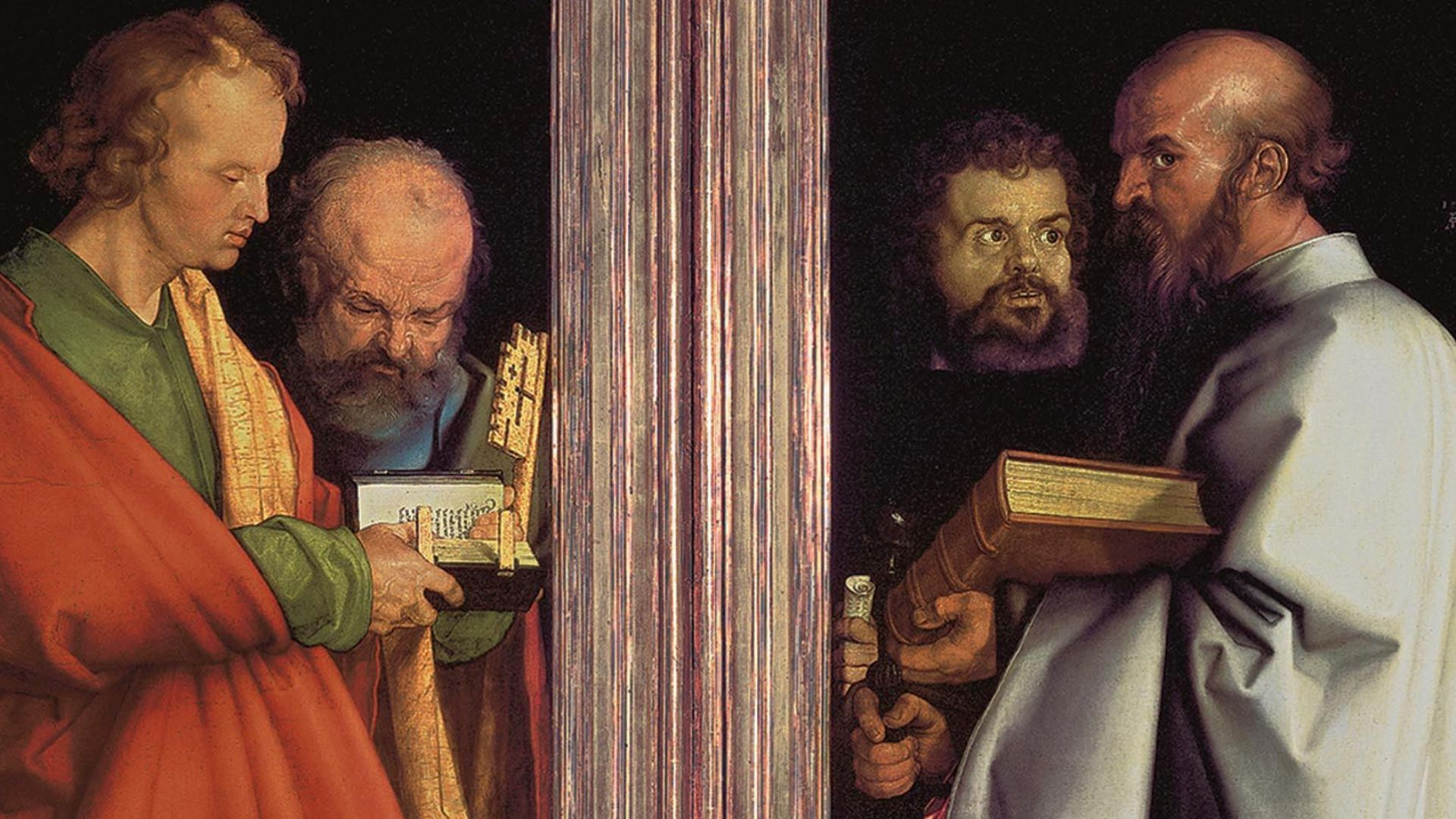

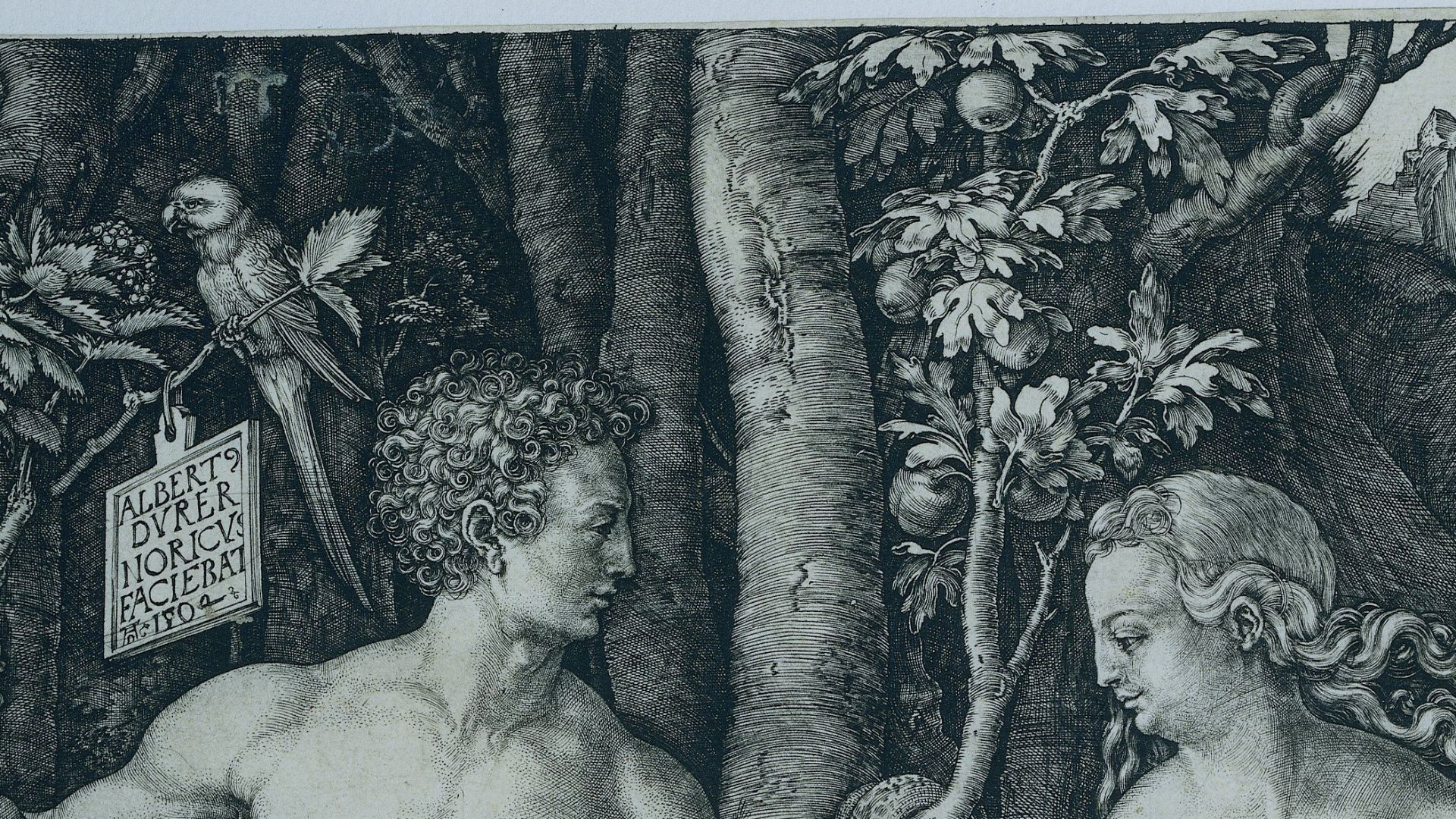

Adam and Eve (1504)

This engraving is a masterclass in human anatomy and Renaissance idealism. Dürer fused Italian proportions with Northern detail, surrounding the figures with symbolic creatures representing philosophical ideas. The result remains one of his most technically sophisticated works.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

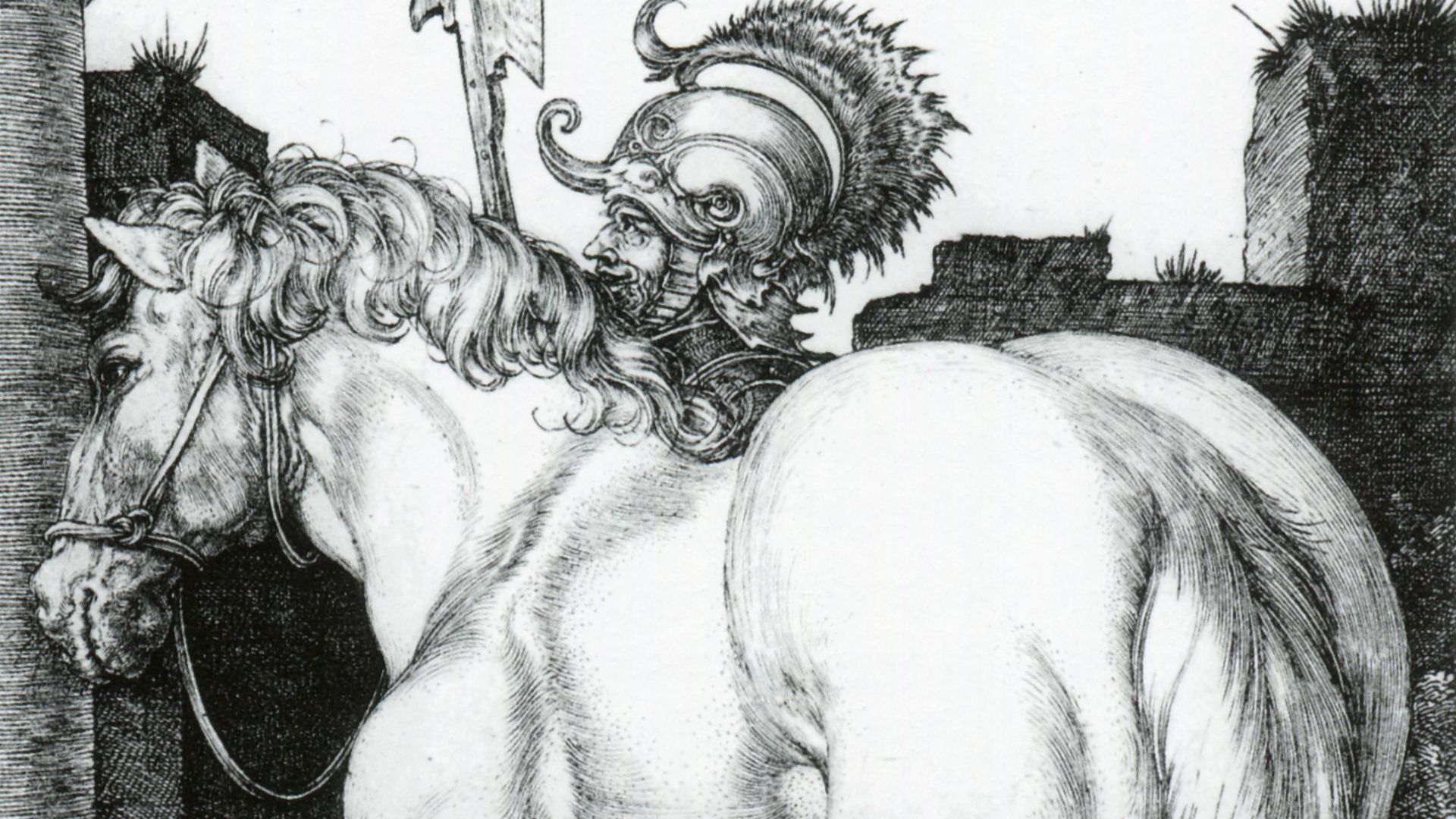

The Large Horse (1505)

This engraving reflects Dürer’s study of Italian anatomy and proportion. The powerful form of the horse demonstrates his interest in idealized structure and movement. The work helped lay the foundation for later explorations of muscular and anatomical precision.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Second Italian Journey

From 1505 to 1507, Dürer returned to Italy for further study. This period deepened his grasp of anatomy, spatial depth, and ideal beauty. He exchanged ideas with leading artists and theorists, refining the hybrid style that would define his most celebrated works.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Copyright Battles in Venice

When Venetian printmakers forged his monogram on counterfeits, Dürer sued them, making one of history’s earliest legal claims of artistic authorship. Although he won partial recognition, the case cemented his belief in protecting creative identity and valuing artistic labor.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

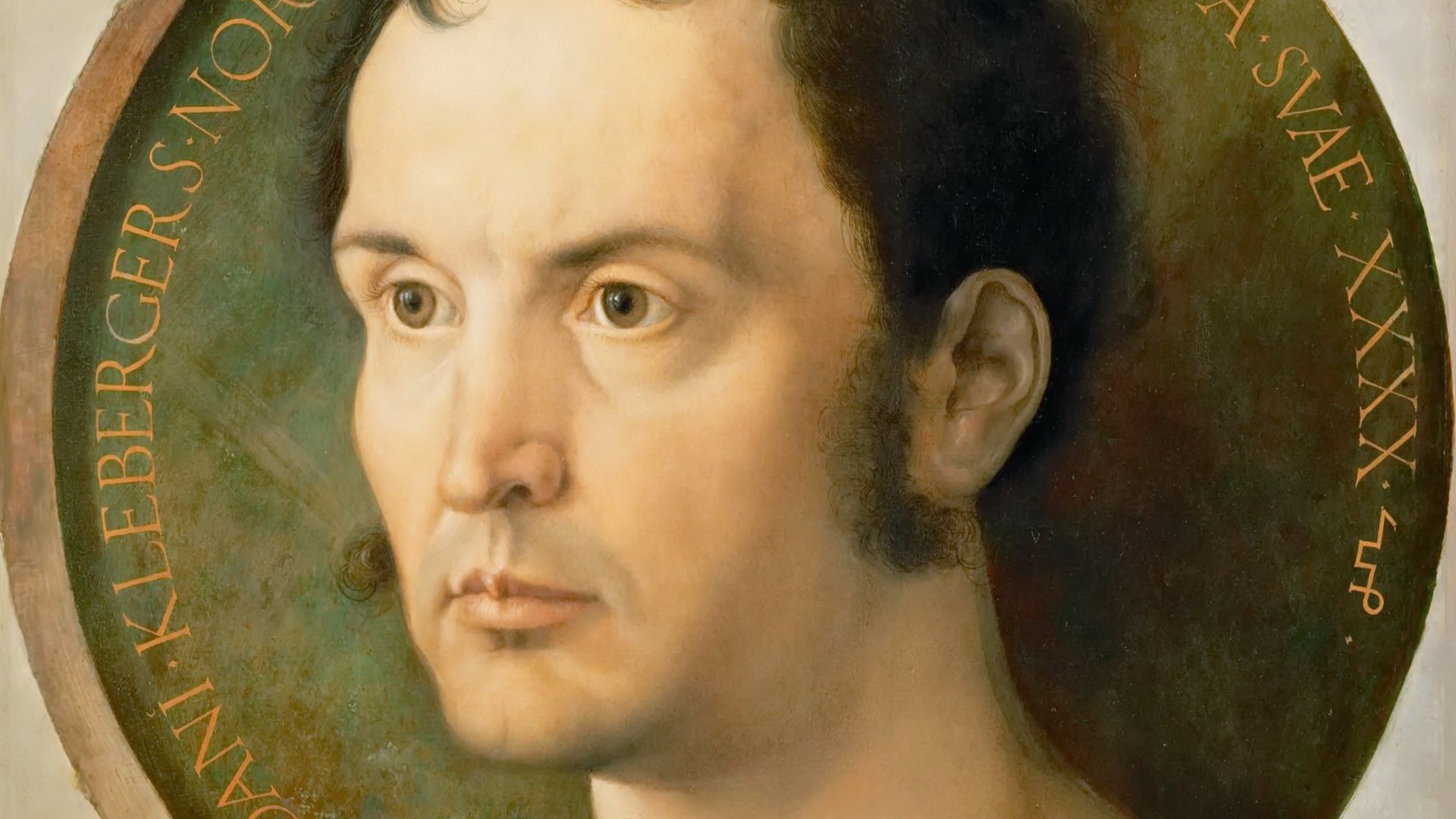

A Motley Crew Of Imitators

Albrecht Dürer’s struggle to protect his work reached its dramatic high point during his time in Venice in 1506, where a talented Italian engraver named Marcantonio Raimondi began producing unauthorized copies of Dürer’s prints. Raimondi not only replicated Dürer’s images line-for-line, he also forged Dürer’s distinctive “AD” monogram, allowing the fakes to circulate widely as if they were originals.

Marcantonio Raimondi, Wikimedia Commons

Marcantonio Raimondi, Wikimedia Commons

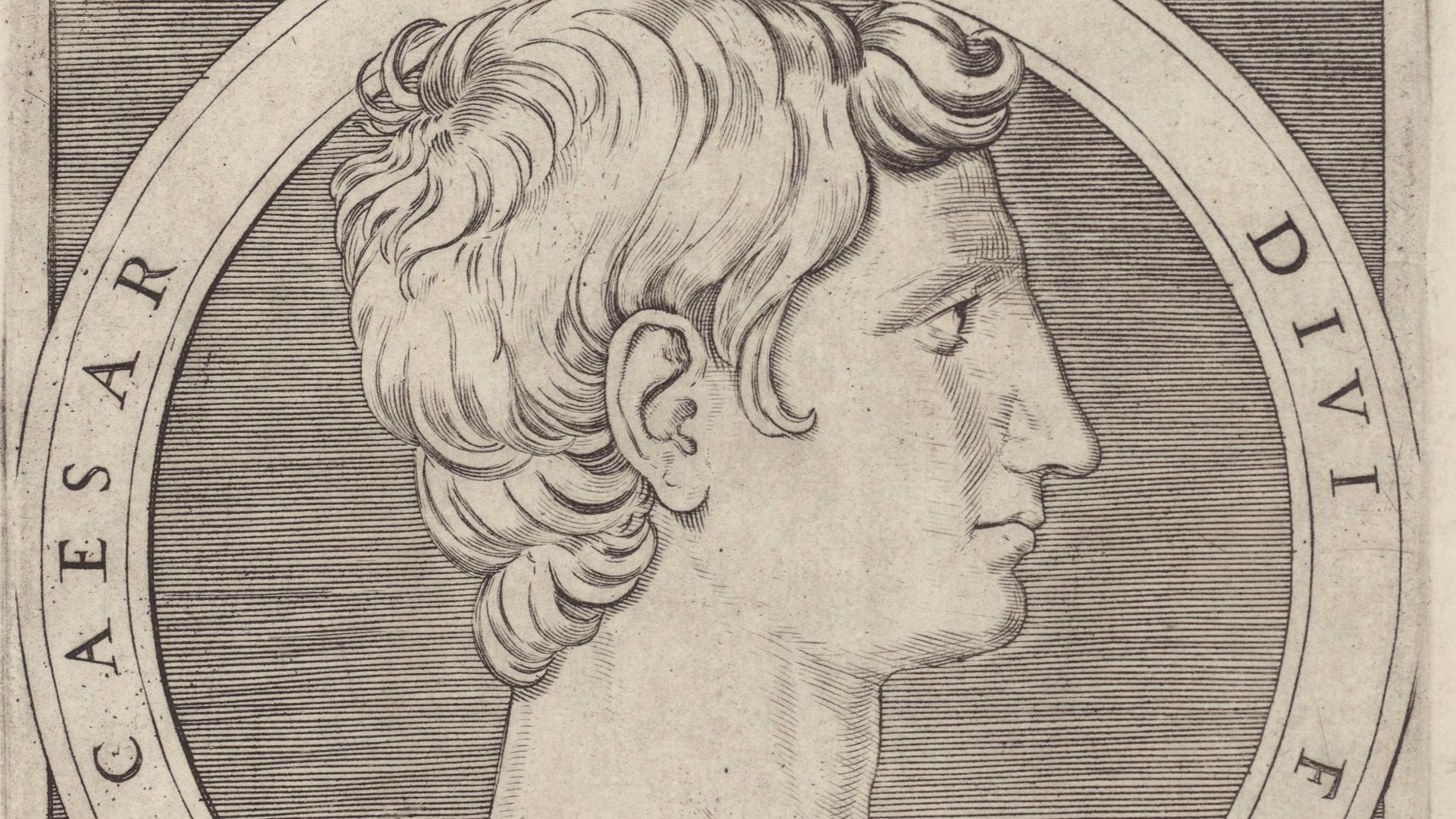

He Was Outraged

Outraged, Dürer confronted Raimondi and brought the matter before the Venetian authorities. For Dürer, the issue was not just financial loss—it struck at the heart of artistic authorship during a time when intellectual property laws barely existed.

non identifié («P. S.»), Wikimedia Commons

non identifié («P. S.»), Wikimedia Commons

A Compromise Was Reached

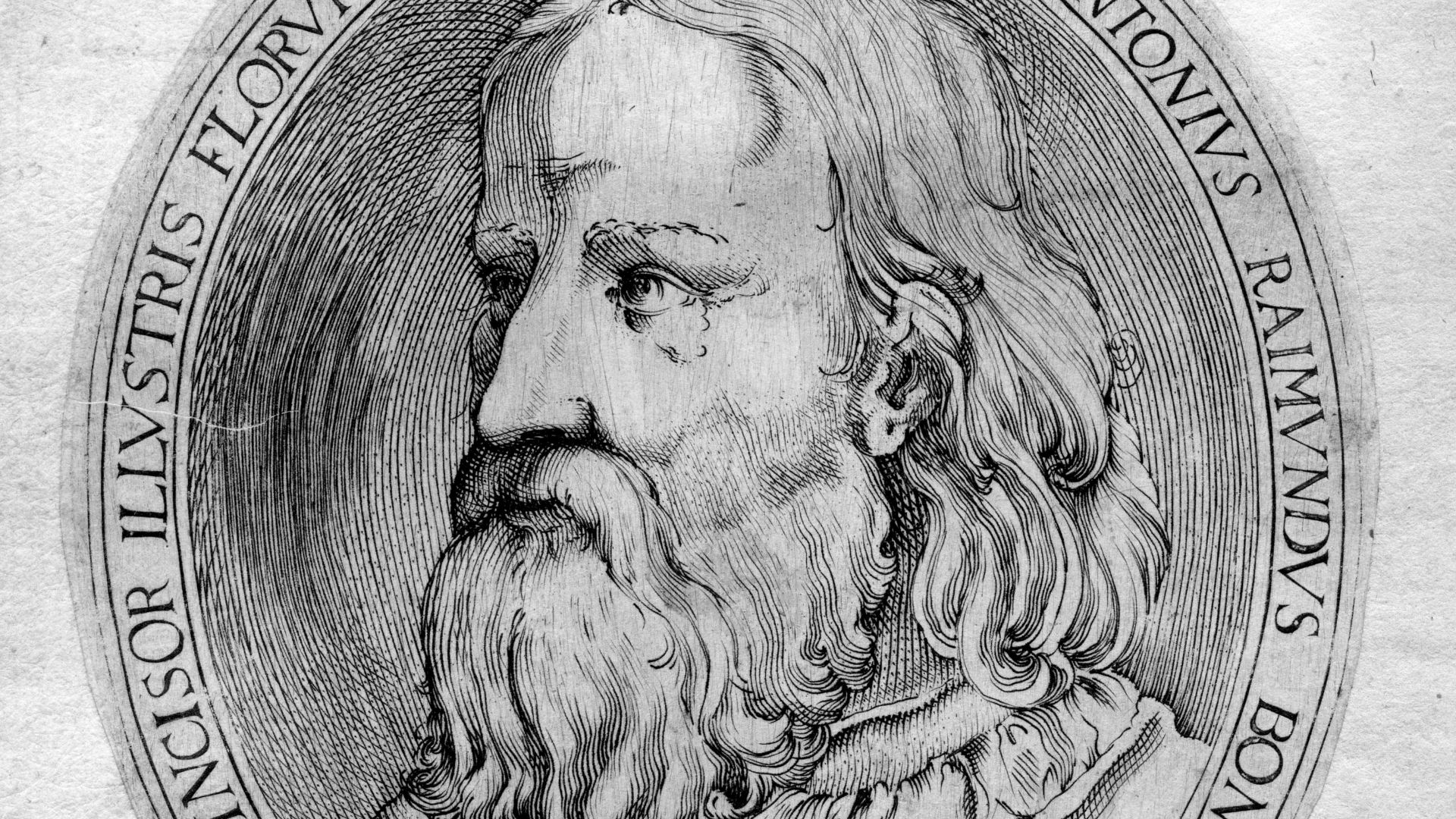

The Venetian court ultimately issued a mixed ruling: Raimondi was forbidden from using Dürer’s monogram, but he was legally permitted to continue copying Dürer’s images themselves. This partial victory frustrated Dürer, but it also became one of history’s earliest formal acknowledgments of artistic identity as something worth protecting.

Giorgio Vasari, Wikimedia Commons

Giorgio Vasari, Wikimedia Commons

His Name Was Upheld

Although Dürer couldn't stop Raimondi from reproducing his work, the case strengthened the prestige of his brand and helped establish a precedent for the idea that an artist’s signature—and by extension, their reputation—held real commercial and legal value.

Raimondi, Marcantonio (1480?-1534?). Graveur, Wikimedia Commons

Raimondi, Marcantonio (1480?-1534?). Graveur, Wikimedia Commons

Knight, Death and the Devil (1513)

A lone knight rides fearlessly through symbolic dangers in one of Dürer’s most powerful engravings. Its meticulous cross‑hatching and philosophical depth explore themes of courage, mortality, and moral integrity. The work is still celebrated as a pinnacle of engraving technique.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

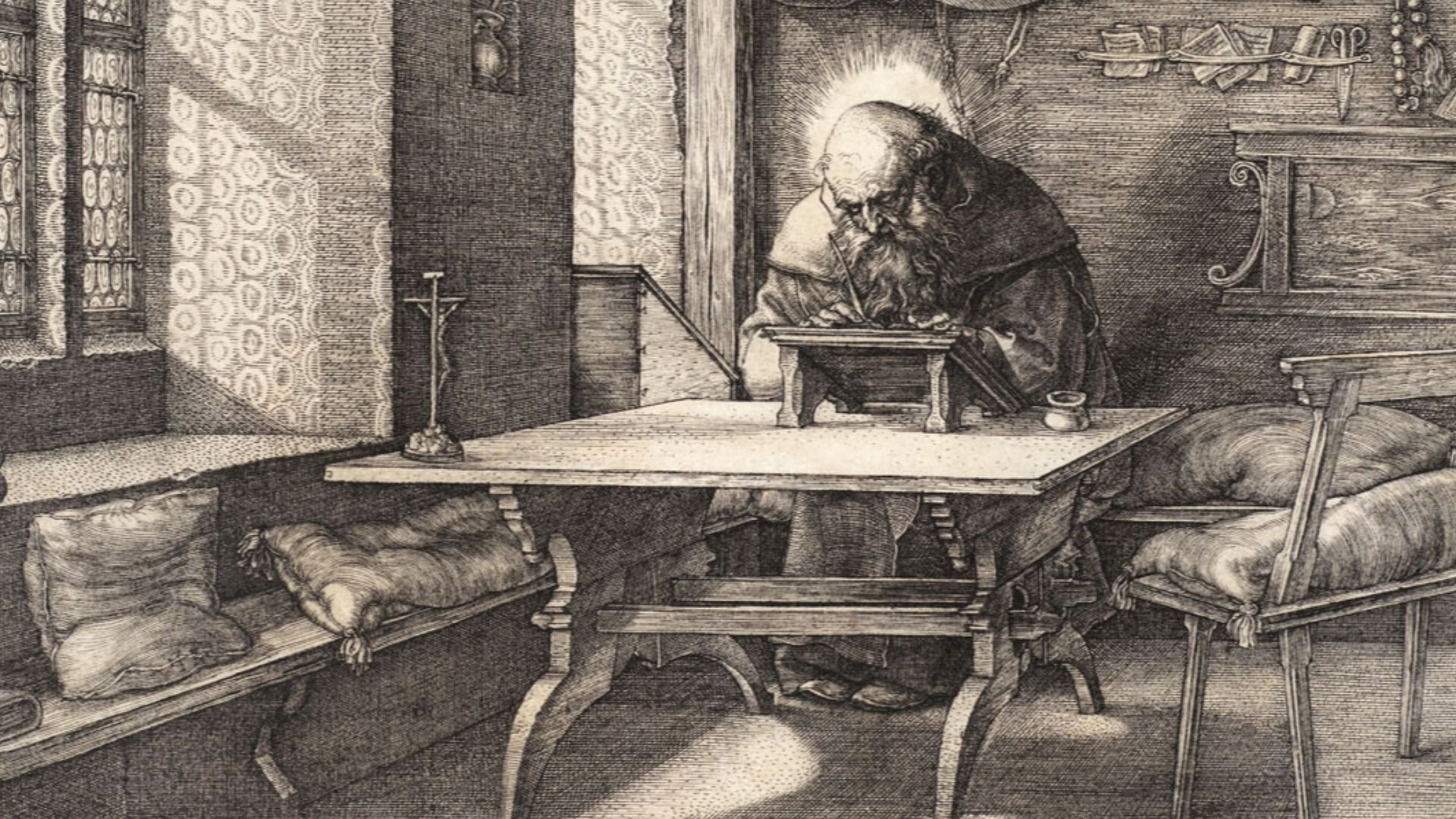

Saint Jerome in His Study (1514)

This engraving depicts Saint Jerome surrounded by symbols of scholarship, domestic quiet, and contemplation. The precise rendering of light and space creates a deeply meditative atmosphere, highlighting Dürer’s ability to construct mood through architectural detail.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Melencolia I (1514)

One of the most studied images in art history, this engraving presents an angelic figure lost in thought among mathematical tools and symbolic objects. It reflects Dürer’s intellectual ambition and his preoccupation with the challenges of finding new sources of artistic inspiration.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

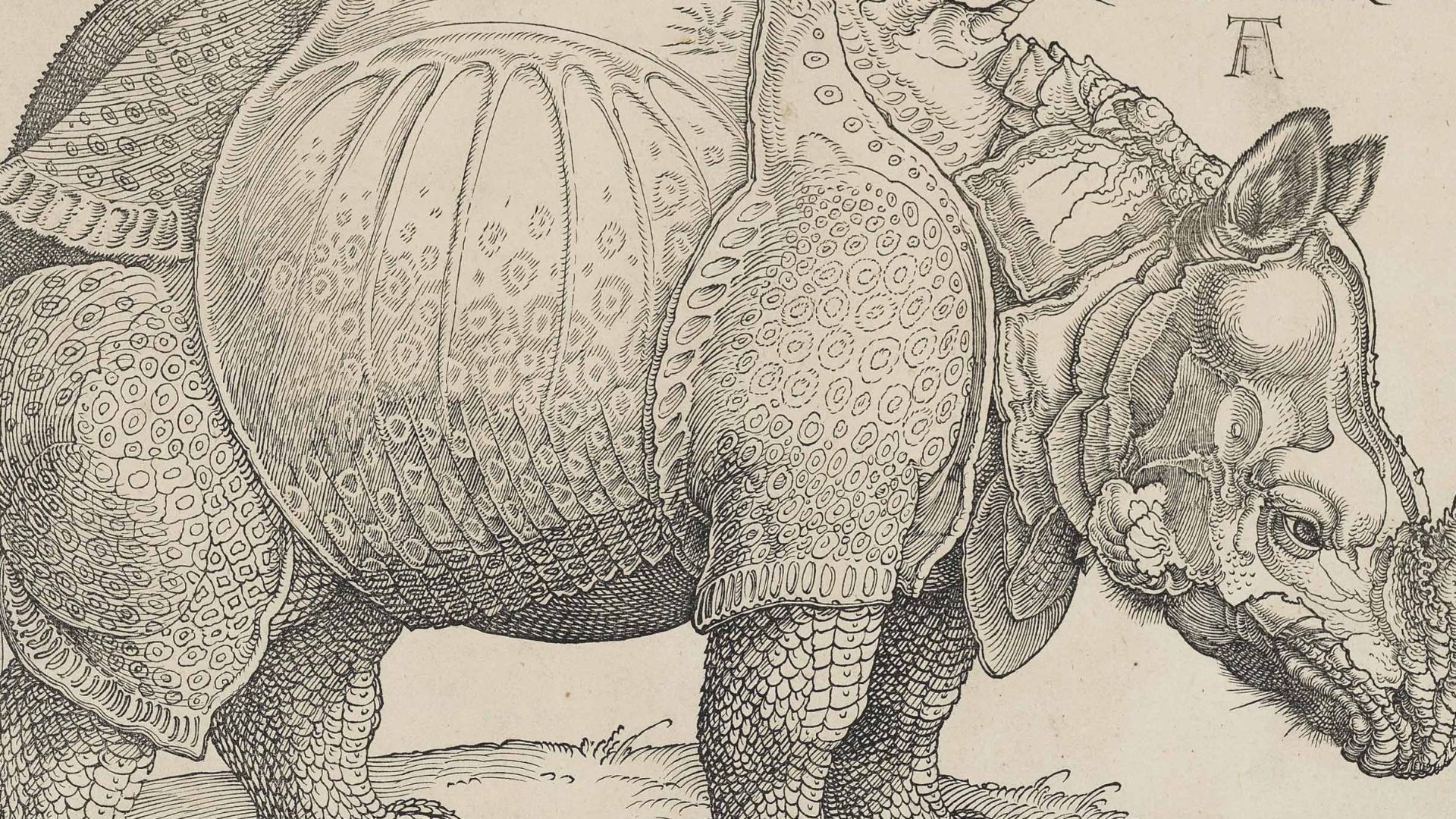

The Rhinoceros (1515)

Dürer created this woodcut without ever seeing the animal, relying only on descriptions. The resulting image, half real and half fantastical, shaped European understanding of the rhinoceros for centuries. It demonstrates Dürer’s unique ability to merge imagination with observational discipline.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

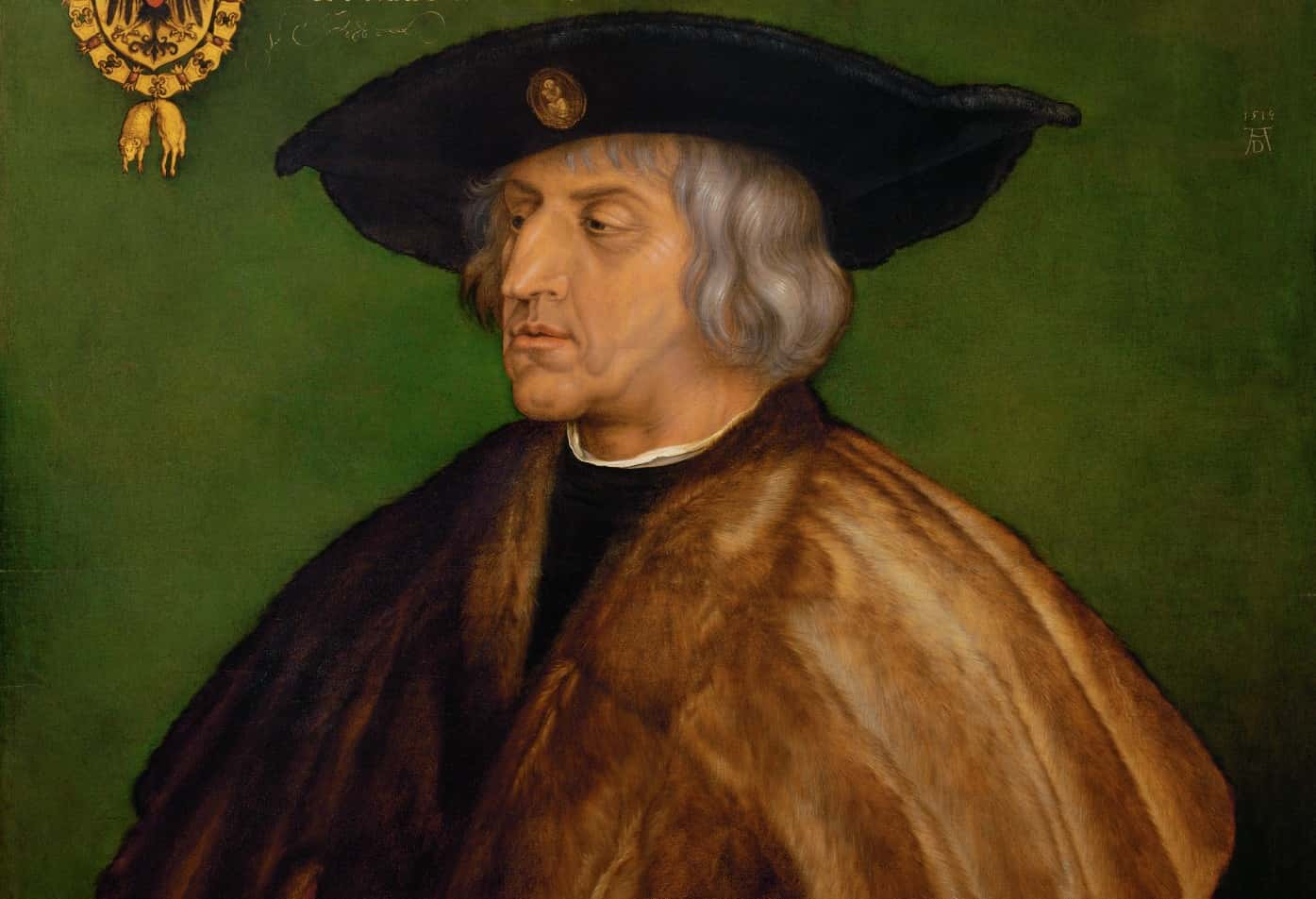

Imperial Commissions

Dürer later served as court artist to Holy Roman Emperors Maximilian I and Charles V. He produced triumphal arches, portraits, and symbolic works that blended political messaging with artistic innovation. These commissions brought wealth, prestige, and lasting influence.

Humanist And Scholar

Dürer always paid extreme attention to what he was doing, and thought long and hard about why he was doing it. He wrote treatises on measurement, geometry, human proportion, and fortification design. His work helped merge artistic practice with intellectual inquiry, solidifying the idea of the artist as a learned figure.

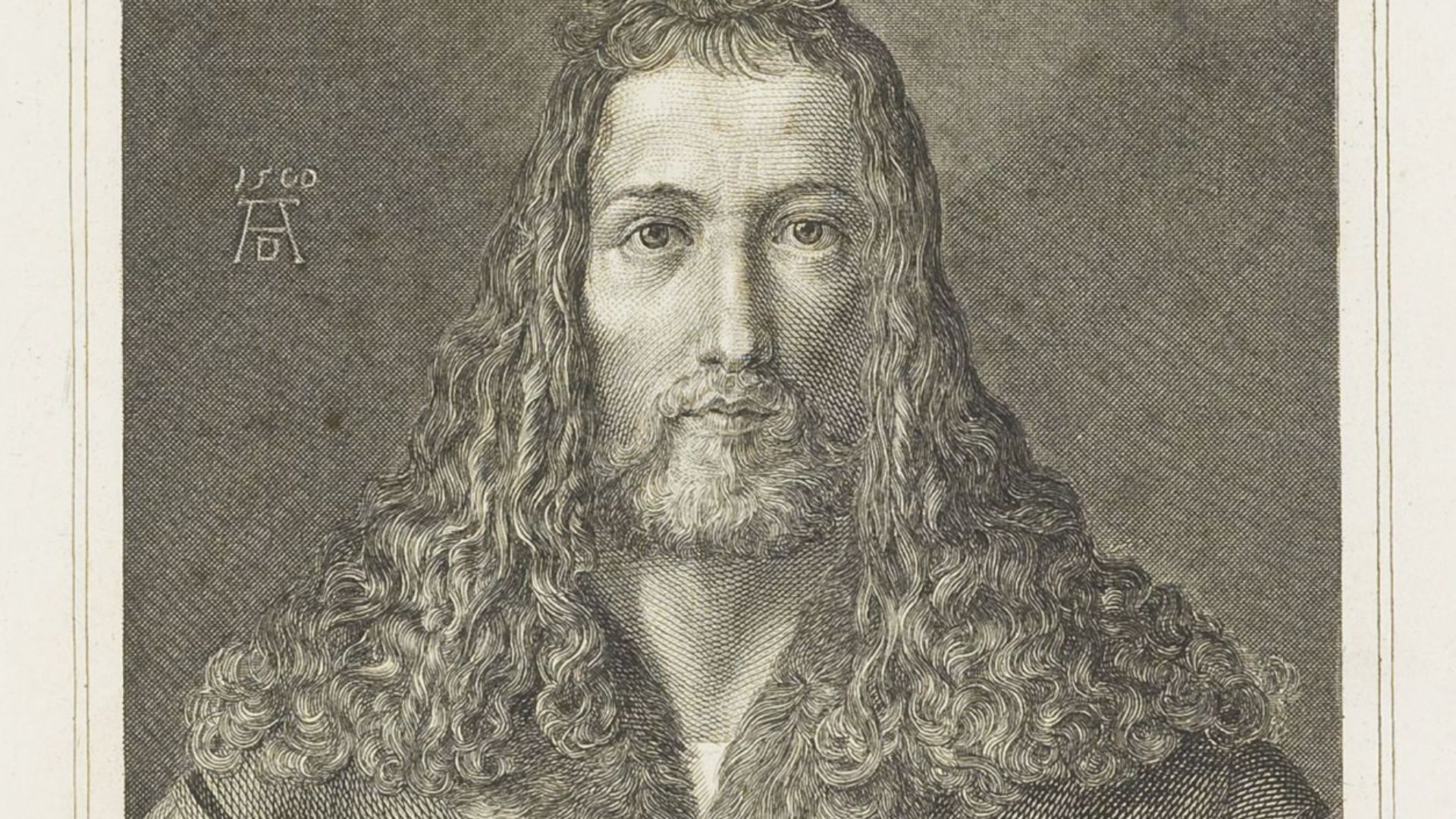

A New Artistic Status

Through self‑promotion, distribution networks, and intellectual engagement, Dürer helped transform the social standing of artists. He demonstrated that creators were not mere craftsmen whiling the days away on idle pursuits; but thinkers, innovators, and individuals worthy of recognition and respect.

Wenceslaus Hollar / After Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Wenceslaus Hollar / After Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Last Years

Albrecht Dürer’s final years on this earth were marked by illness, probably caused by his wide travelling. He complained of persistent fevers, weakness, and pain, symptoms historians generally link to malaria; it’s impossible to be certain. Dürer passed away in Nuremberg in 1528 at age fifty-six, still working busily despite his declining health. His wife Agnes carried on selling his works until she, too, passed away in 1539.

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Albrecht Dürer, Wikimedia Commons

Why Dürer Endures

Dürer’s work remains compelling because he merged technical brilliance with insatiable curiosity about the world. His prints, studies, and theories continue to inspire artists, scholars, and viewers, securing his place as a foundational figure of Western art history.

Rijksmuseum, Wikimedia Commons

Rijksmuseum, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

Legendary Facts About Michelangelo, Master Of The Renaissance

Inventive Facts About Leonardo da Vinci