A Betrayal Most Foul

Known as one of the most skilled and ruthless commanders in history, Julius Caesar spent his life taking what he wanted with few people willing or able to stop him. After getting a taste of power and glory at a young age, he knew his destiny was to rule in one way or another. However, he made countless enemies, especially among those closest to him, so although he believed he was untouchable—others greatly disagreed.

1. He Was Divine

Following his birth in July 100 BC, Gaius Julius Caesar quickly began to display certain qualities of strength, cunning, and ruthlessness that seemed to prove he was born to rule. Tying all of this together, though, was his ambition, pushing him to strive for power right to the end. This was surely in his blood, as his family claimed a descent from the gods, allegedly tracing back to the mythical hero Aeneas, whose mother was the goddess Venus.

Likewise, his early vocation also had to do with the divine.

Clara Grosch, Wikimedia Commons

Clara Grosch, Wikimedia Commons

2. He Took A Career Path

Sometime between 87 and 84 BC, Caesar’s father retired from his time as a politician, and surprisingly, Caesar didn’t take up the reins—not immediately, anyway. Instead, he became a priest of the god Jupiter, which specifically forbade his involvement in a political career. Stemming from this decision, he soon married Cornelia, the daughter of Consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna.

They would soon be in for trouble, though.

3. He Went Away

In 82 BC, the Roman general Sulla triumphed over an opposing faction led by Consul Cinna, Caesar’s father-in-law. Soon after, Sulla ordered Caesar to abdicate his position and divorce Cornelia. Not one to give up easily, Caesar refused and went into hiding until others convinced Sulla to compromise, allowing Caesar to stay married but resign his priesthood.

This was far from his last difficult situation.

4. They Captured Him

Caesar couldn’t even avoid problems when he tried to, including on one trip to Rhodes in 75 BC, when he was simply seeking an education. During this journey, he became delayed when a band of pirates took him for ransom. Still, he remained calm and collected, and even told them to demand a higher price for him, which was soon paid.

Unfortunately for them, he didn’t let this go.

Raffaello Schiaminossi, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Raffaello Schiaminossi, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

5. He Came Back

Once the pirates received their ransom money, they released Caesar—which they soon regretted. Although he had appeared unfazed during his capture, he wasn’t about to let their audacity slide. In turn, he hunted them down with the help of an entire naval fleet and took them captive before ultimately executing them.

Naturally, he made quite the impression on those around him.

6. They Chose Him

After Caesar had finished his time abroad, he returned to Rome and wasted no time in beginning his life as a politician. He had already received an appointment as a pontiff in place of his late relative, which gave him a distinct social advantage. Therefore, in 71 BC, an election granted him the position of a tribune in the Roman army.

Of course, he would only aim higher.

7. He Joined For Life

Only a couple of years later, in 69 BC, Caesar received another appointment to the position of quaestor of one of the Roman provinces. This not only allowed him to serve under the praetor Gaius Antistius Vetus, but also gave him stability, as it came with a lifetime seat in the Roman senate.

Abel de Pujol, Wikimedia Commons

Abel de Pujol, Wikimedia Commons

8. He Lost His Wife

Caesar had several possible children during his lifetime, but only one was legitimate. Cornelia gave birth to their daughter, Julia, in 69 BC. However, disastrous news soon followed, as Cornelia subsequently passed—possibly due to the birth. Still, Caesar wouldn’t spend too long in grief, marrying General Sulla’s granddaughter, Pompeia, soon after.

He was just as quick to return to work.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

9. He Backed Him Up

Around this time, Caesar cultivated one of the most significant relationships in his life as he became increasingly connected to one of Rome’s other renowned generals. Pompey the Great was fighting to enact several laws and elevate his authority, for which Caesar advocated and eventually joined him.

This helped him gain further support.

10. He Beat Them

63 BC held multiple chances for Caesar to further his goals, as he ran both for the praetor’s office and that of pontifex maximus. While some sources claim his tactics included paying bribes and endearing himself through flattery, this has never been confirmed. Still, even against numerous already-influential figures, he won both positions.

This all came at a cost, however.

11. He Was Broke

Caesar had succeeded in both the pontifical election and the one for the praetorship, but in doing so, he had accumulated a significant debt from the campaigns. Seeing no other option, he embarked on a conquest against the Lusitani and Callaeci people, in which he collected more than enough plunder to settle what he owed.

Following this, he faced a big decision.

12. He Made His Choice

There was certainly more to gain in completing his conquest, but something stopped him from continuing. In 60 BC, the law impeded his desire to run for a consulship, as it said he had to be physically present to declare his candidacy. Caught between his command and his political ambition, he chose to abandon his campaign and enter the race.

Fortunately, he wasn’t alone.

13. He Had Support

Through his campaigns—both political and militaristic—and possibly through schmoozing and bribery, Caesar garnered a fair amount of backing. Additionally, he not only benefited from his work with Pompey but also earned the favor of Consul Marcus Licinius Crassus. With this amount of endorsement, it’s no wonder that he won the consulship in 59 BC.

Of course, this led to a much stronger alliance.

14. They Came Together

Caesar had won the authority of a consulship, but still wanted to cement that power and make it something more, which he would need help for. Although Pompey and Crassus were adversaries, Caesar found a way to bridge their differences as he saw their collective potential. From this, the alliance of the First Triumvirate between the three consuls emerged.

This prompted another union.

15. He Married Her

Caesar took steps to fortify the First Triumvirate alliance, including one that he was already familiar with—marriage. However, seeing as he was already married to Pompeia, he offered the hand of his daughter, Julia, in marriage, which Pompey accepted. However, more conflict was on the horizon.

Alexander (2004), Warner Bros.

Alexander (2004), Warner Bros.

16. He Stopped Them

In 58 BC, Caesar returned to active duty as he initiated the first of many campaigns against the people of Gaul, during which he grew his reputation for strategic prowess. In his first battle, he built a wall to halt the migrating Helvetii people from travelling through Rome, defeating them before sending the survivors home.

He had plenty more victories to achieve, however.

17. He Kept Winning

Although Caesar was not wholly undefeated, his brilliant tactical mind and unwavering leadership earned him more and more victories against the Gauls. By 56 BC, he and his armies had proven their might enough that he was able to spread his forces out and bring almost all of the Gaul people under Rome.

Still, these weren’t his last impressive feats in this conflict.

18. He Bridged The Gap

His campaigns against the people of Gaul were going well, but Caesar still wanted to bolster his rising reputation as a Roman commander. After defeating a force of Germans crossing the Rhine River, he constructed a bridge in that spot, creating the first of its kind. This added to his resume and demonstrated the strength behind Rome.

Fortunately, there’s a reason historians know all of this.

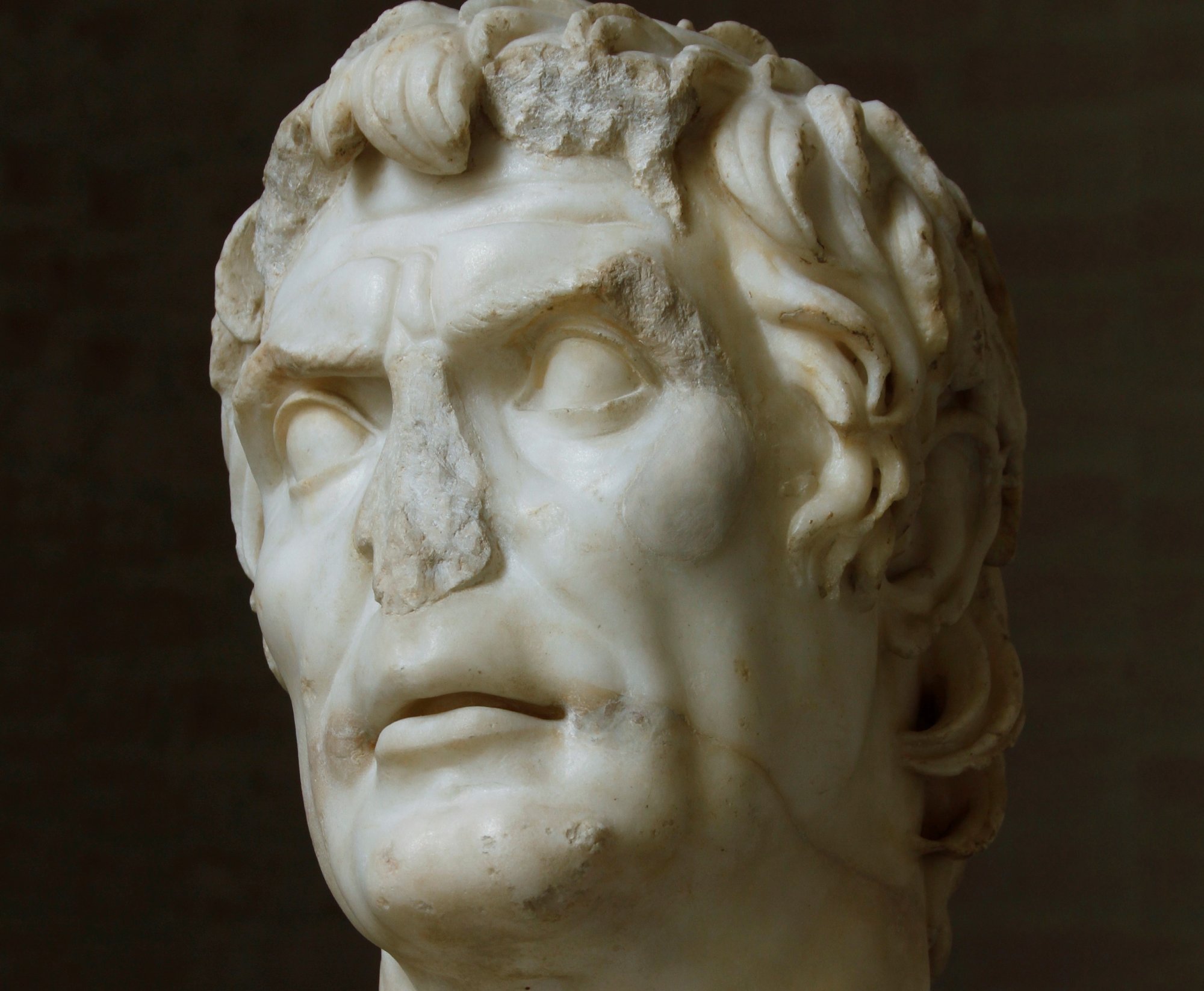

© José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, Wikimedia Commons

© José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, Wikimedia Commons

19. He Wrote Everything Down

Throughout his years of fighting in Gaul, Caesar was meticulous in his chronicling of the operations, emerging from the conflict with ten volumes of battle records. While it's impossible to avoid Caesar’s bias in his writings, these remain some of the only surviving records of the Gallic conflicts, and many of his contemporaries regarded them as masterpieces.

Meanwhile, things were falling apart back home.

Weston, W H; Plutarch; Rainey, W, Wikimedia Commons

Weston, W H; Plutarch; Rainey, W, Wikimedia Commons

20. They Fell Out

Caesar had created quite an imposing reputation and achieved much in his conquest, but he had also caused a rift between himself and the other Triumvirates. By 57 BC, they were already experiencing poor results from the elections, and both Pompey and Crassus begrudged Caesar’s victories as they wanted commands of their own.

Still, this wasn’t the worst of it.

21. He Fell

Passing into 53 BC, the First Triumvirate had fallen to infighting and feelings of resentment, but that year saw its first real loss. In an effort to prove himself against the renown of Caesar and Pompey, Crassus launched a campaign against Parthia. However, this didn’t turn out well for him, and he perished at the Battle of Carrhae.

With the First Triumvirate shrinking, Caesar’s return was becoming more desirable.

22. They Wanted Him Back

With Caesar still in Gaul and Crassus having perished, Pompey was virtually alone in Rome—and his resentment turned into distrust. His fellow consuls echoed this sentiment and, wanting to avoid any issues, proposed that Caesar and his army return as they had finished in Gaul. In reality, although he was close to being done, Caesar was still busy fighting.

Therefore, the Senate needed help.

23. He Turned Against Him

In the end, the proposal of those in the Senate who wanted to return Caesar to Rome was met with a veto, so its issuers turned to someone closer to Caesar. Knowing that Pompey was growing more wary of his former ally, they asked him to force Caesar’s return, and successfully put the final nail in the coffin of the First Triumvirate’s alliance.

This quickly escalated.

24. They Prepared

While these political developments were happening in Rome, Caesar wasn’t ignorant of any of it, nor where it was surely leading. Recognizing that a civil conflict was likely to break out soon, Caesar built up his forces in Gaul, but he wasn’t the only one. Fearing the same thing, Pompey and his allies also strengthened their armies.

Ultimately, they made their stance clear.

25. They Antagonized Him

After several unsuccessful proposals for both Caesar and Pompey to agree to disarmament, and amid rumors that Caesar had begun his march, the Senate made a decision. There would be no making peace with Caesar, and after expelling his supporting tribunes, they officially declared Julius Caesar an enemy.

In retrospect, he likely had a few reasons to be upset.

26. They Made Him Choose

Despite his extensive records, Caesar’s exact motive at this time remains the subject of debate. While it clearly all stemmed from tense political relations with Pompey and the Senate, it also likely came from being forced into a corner. With him refusing the order for his return, his only options were to face prosecution or declare hostilities against Rome.

Finally, he determined his fate.

27. He Crossed The Line

Once word reached Caesar that Rome had declared him an enemy, he knew it was time to fight. In January 49 BC, he took one legion across the Rubicon river, which served as Italy’s northern border—allegedly stating, “Let the die be cast”. As this essentially kicked off the civil conflict, the phrase “crossing the Rubicon” has come to mean “passing the point of no return”.

As for his opponents, they were shaking in their boots.

28. They Ran Away

Caesar’s reputation made his enemies think twice about engaging him and, assuming correctly that he was marching on Rome, numerous senators escaped to the south—as did Pompey. To his credit, Caesar did try to open negotiations, but when they didn’t work, he resolved to establish communication by force.

Of course, Caesar targeted one man first.

29. He Appointed Him

Pompey soon fled to Greece, and wanting to capture his former ally to force negotiations, Caesar decided to goad his reaction. Leaving his praetor Lepidus to preside over Italy, Caesar turned his forces against the provinces in Spain that belonged to Pompey, and whose legates then either fell to Caesar or surrendered to him.

As in everything, he simply took what he wanted.

30. He Installed Himself

Once Caesar had finished in Spain, he returned to Rome and assumed the role of dictator, which, in ancient Rome, usually meant receiving full authority to tackle a specific issue. This was through a law enacted by Lepidus—and it gave Caesar the ability to hold elections himself. As a result, his power only grew.

31. They Won

With Pompey gone, Caesar used his powers as dictator to open up the elections for new consuls, which was only a means to regain his station. Running for the consulship with Senator Publius Servilius Isauricus, the two won in 48 BC. Having re-established his consul position, Caesar resigned his dictatorship and resumed the hunt for his enemies.

This proved more difficult than he thought.

32. They Scattered

Hot on Pompey’s trail, Caesar soon caught up to him in Greece and, after some back and forth, forced Pompey to run to Egypt. While many of Caesar’s other enemies escaped to different places in Africa, some decided to play nice and beg for his pardon, such as the politician Marcus Junius Brutus.

This accomplishment was well-received back home.

33. He Became A Tyrant

In response to his victory over Pompey in Greece, Rome again appointed Caesar to the position of dictator, but this time for a full year. Meanwhile, things weren’t going nearly as well for Pompey, who arrived in Alexandria in November 48 BC, only to quickly perish under the orders of King Ptolemy XIII, who hoped to gain Caesar’s favor.

Caesar wouldn’t be so easily swayed, though.

Hubertus Quellinus, Wikimedia Commons

Hubertus Quellinus, Wikimedia Commons

34. He Helped Her

King Ptolemy wanted Caesar’s aid in his own civil conflict for the rule of Egypt, which he was fighting against his sister, Cleopatra. However, the slaying of Pompey didn’t have the desired effect, and although Caesar arrived in Egypt and agreed to settle the conflict, he was in support of Cleopatra.

The ensuing fight didn’t take long.

35. They Were Victorious

Caesar’s involvement in Egypt’s civil conflict lasted a matter of months, during which he helped Cleopatra withstand several sieges by her brother. In the end, Caesar’s tactical mind proved superior, and he emerged the victor of the Battle of the Nile, during which Ptolemy perished. Following this, Caesar installed Cleopatra as Egypt’s ruler.

Naturally, this was cause for celebration.

36. They Got Together

During their alliance against Ptolemy, Caesar and Cleopatra had begun an affair, and celebrated their victory together with a lavish procession on the Nile. Despite his work in Egypt being done, Caesar remained with Cleopatra for a few more months, and she would later give birth to their illegitimate son, Caesarion.

Eventually, though, he had to leave. HBO, Rome (2005–2007)

HBO, Rome (2005–2007)

37. He Was Surprised

Caesar enjoyed the company of Cleopatra and the gift of relaxation for a bit, but was soon in for another fight. In recent months, King Pharnaces II tried to reclaim Pontus, as it had once been the kingdom of his father. However, in the process, he tore through Caesar’s legates and client kings in the region, much to Caesar’s shock as he arrived in Antioch.

To Caesar, though, Pharnaces was just another obstacle.

38. He Conquered

King Pharnaces likely believed he had a shot at defeating Caesar, as he had already bested some of his forces. However, this belief was short-lived as Caesar met the King in the Battle of Zela and made quick work of his armies. This swift victory prompted Caesar to write the now-famous quote “veni, vidi, vici,” which translates to, “I came, I saw, I conquered”.

Following this, he finally met some serious resistance.

39. He Had Issues

After a brief return to Italy in 47 BC, Caesar departed once again to pursue another enemy senator, Cato the Younger, who had fled to Africa. This time, though, Caesar’s arrival in Africa was quickly hindered by an inability to establish a beachhead, followed by a defeat at the hands of Titus Labienus, which made him rethink his strategy.

This campaign didn’t end how he expected.

40. He Found Them

After taking a step back, Caesar once again pushed forward into Africa, using decidedly more careful methods in battle. Fighting through Cato’s forces and finally reaching him in Utica, Caesar found a shocking sight. Rather than fight Caesar or beg his pardon, Cato had taken his own life, and Caesar then learned that many of his remaining enemies did the same.

At last, the conflict was drawing to a close.

41. He Ended It

For his recent victories, Caesar took a small break from fighting to throw a couple of big parties in celebration. However, in early 45 BC, he returned to hunting down his opposition. In one final engagement on March 17, known as the Battle of Munda, he eliminated nearly all his surviving enemies and ended the larger conflict.

This granted him even further acclaim.

William Cho, CC BY-SA 2.0 , Wikimedia Commons

William Cho, CC BY-SA 2.0 , Wikimedia Commons

42. He Was Honored

Having emerged triumphant from his civil conflict, the Senate rewarded Caesar with a level of power that was unprecedented for him. Beyond practical honors, he also received several symbolic rewards such as a golden seat in the Senate, having his face on Roman coins, and the changing of his birth month from Quintilis to Julius—although it’s now called July.

With his great influence over Rome, he had big plans.

43. He Got To Work

Since his first appointment as dictator, Caesar had assumed the role several more times, and in 46 BC, he was elected for the next ten years. With his newfound authority, he introduced several reforms, like reducing government taxes, supporting veterans, and implementing the Julian calendar. However, he did little to change the Republican system at its center.

Still, not everyone was happy with him.

44. They Spoke Out

Caesar had overcome his most dangerous opponents, but there were still those who opposed him. This only got worse as he exerted his will unchecked, such as when two Tribunes took a man into custody for referring to him as “rex” or “king”. Caesar saw this as an insult to his honor and ordered the removal of the Tribunes from office.

Unfortunately, his influence only grew.

45. He Took His Title

While the anger of Caesar’s enemies in Rome grew and more of the public turned against him, they could at least take comfort in the hope that his rule would end after ten years. This was until February 44 BC, when he assumed the position of dictator perpetuo, otherwise known as “dictator for life”. Suddenly, any promises to ensure a free republic fell away.

This pushed more than a few over the edge.

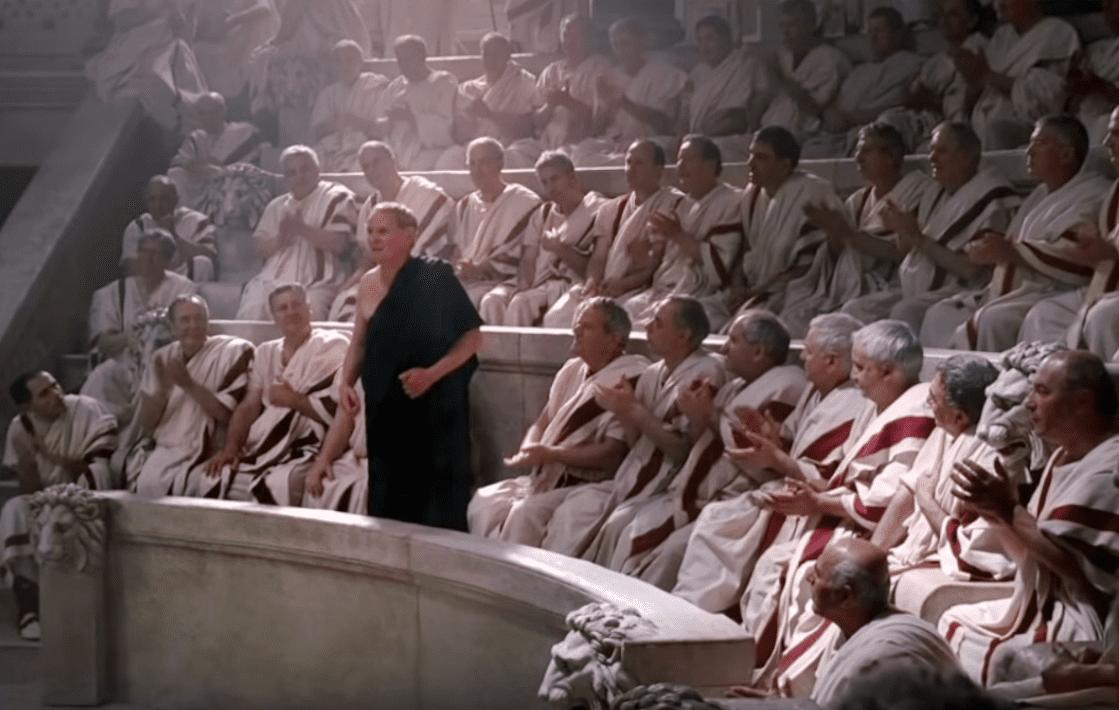

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Léon Gérôme, Wikimedia Commons

46. They Started Scheming

By mid-45 BC, numerous politicians realized that if they were to stop Caesar and ensure the future they saw for Rome, his life needed to end. Over the following year, the conspirators grew to around 60 men—a mix of those from either side of the previous civil conflict. At the helm were a few leaders, with the most prominent being Marcus Junius Brutus.

However, time was running short.

Vincenzo Camuccini, Wikimedia Commons

Vincenzo Camuccini, Wikimedia Commons

47. He Was About To Leave

The conspirators decided Caesar’s fate, but they still needed a time and place. A Senate meeting was the best choice, as only Senators could attend, but the question of “when” grew more urgent. Since he would soon embark on his Parthian campaign, the group planned for the last meeting before his departure, March 15—also known as the Ides of March.

Strangely, Caesar was none the wiser.

48. He Ignored Them

Caesar’s ambition and ego had maybe grown too big for his well-being, since even though there were rumors of the conspiracy, he refused to take any safety measures. Of course, he would soon come to regret this decision on the Ides of March, when the conspirators surrounded his golden throne during the Senate meeting and drove their daggers into him.

As with many great leaders, his final moments have been dramatized since then.

49. He Had A Famous Line

Julius Caesar perished almost immediately, and it’s no wonder, considering he received 23 stab wounds. The accounts of his last seconds alive vary, with some saying he was silent as he fell. On the other hand, a popular telling states that upon seeing Brutus come forward, Caesar uttered the words, “Kai su, teknon?” which translates to, “You too, child?”

Thus, his reign ended, and another began.

50. His Heir Took Over

In the decade following Caesar’s demise, his assassins didn’t exactly get the change they were hoping would come from their conspiracy. Shortly after the Ides of March, large-scale rioting in response to Caesar’s slaying forced the perpetrators to flee, and Caesar’s legacy soon became that of a fallen hero. Furthermore, the Republic of Rome never returned, with Caesar’s heir, Augustus, creating a new Roman Empire in its place.

You May Also Like:

The Truth About Brutus, The Man Who Killed Caesar

The Cruel Truth About Nero, Rome’s Worst Emperor