"You nobles, you sons of my leading men, soft and dandified, trusting in your birth and your wealth, paying no attention to my command and your advancement, you neglected the pursuit of learning and indulged yourselves in the sport of pleasure and idleness and foolish pastimes. By the King of the heavens I think nothing of your nobility and your beauty. Others can admire you. Know this without any doubt; unless you rapidly make up for your idleness by eager effort, you will never receive any benefit from Charlemagne".

To some, he was Charles the Great; to others, Charles the Cruel. One thing is for certain, Charlemagne remains one of the most influential leaders in western history. As Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne united diverse peoples across the European continent, instituted a culture of learning and scientific advancement which would rival the Renaissance, and zealously enforced Christianity throughout Europe. While his dynasty did not survive long past his demise in 814 CE, Charlemagne is remembered as the prototypical European monarch, upon whom countless subsequent rulers have based themselves. Here are 42 glorious facts about Charlemagne, the man who today is known as the Father of Europe.

1. Springing Up

No one knows for sure where Charlemagne was born. Historians’ best guess is Aachen, in modern day Germany. Charlemagne’s father, Pepin the Short, had built a palace there to take advantage of the city’s hotsprings, and Charlemagne would reside there for most of his life, although several other cities have also been suggested as his possible origin.

2. Legitimately Interesting

Charlemagne was born out of wedlock. In many such cases, illegitimate children would have been denied their rights to succeed to the throne, or even disavowed completely. Charlemagne seems to have gotten a pass because his parents, Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon, were engaged at the time and married shortly thereafter. Charlemagne’s biographers tended to avoid the fact, never denying it, but not exactly bringing it up, either.

3. King Me

Charlemagne’s father, Pepin the Short, was not, technically, the King of the Franks for most of his career. Rather, he was the Mayor to the Palace of Austrasia. Under Pepin’s father, Charles Martel, the mayor of the palace had become the most powerful political gig in the kingdom—more powerful, eventually, than the king himself. Pepin inherited the role of mayor and, in 749, Pope Zachary decided it just made more sense for Pepin to be considered King of the Franks.

4. Sibling Rivalry

After Pepin’s demise, Charlemagne inherited the Frankish kingdom. So did his brother, Carloman. The two brothers did not get along, and were constantly seeking ways to oust the other from the throne. Though she had lost her role upon the passing of her husband, ex-queen and royal mother Bertrada hung around the palace for the express purpose of breaking up fights between Charlemagne and Carloman, though by all accounts she seems to have favored the former.

5. Somebody Nose Something

Carloman perished suddenly—and conveniently—in 771, leaving Charlemagne in sole possession of the Frankish kingdom. While one might reasonably suspect foul play, attending doctors assured the people that Carloman’s passing was completely natural and normal. Carloman, they explained, simply perished of a nosebleed. As one does.

Morphart Creation, Shutterstock

Morphart Creation, Shutterstock

6. No Swearing Allowed

In 779, Charlemagne enacted a strange law which forbade guilds under pain of disfigurement, exile, or even death. The idea was to do away with any kind of loyalty oath taken to anyone but Charlemagne himself. The idea was expanded in 802, when a law was introduced requiring any man over the age of twelve to officially swear loyalty to Charlemagne.

7. Typecast

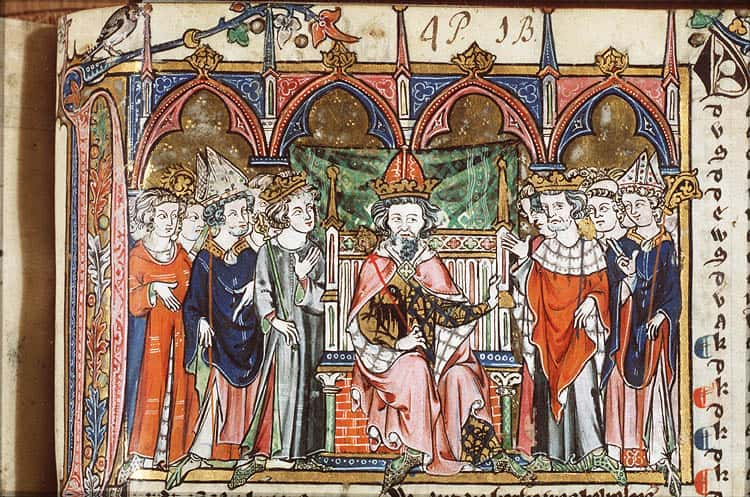

Though he is remembered as the emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Charlemagne was not crowned emperor until 800, by which time he had already unified a massive kingdom. Though he reigned as King of the Franks for 45 years, Charlemagne spent just thirteen of them as Holy Roman Emperor.

8. Voluntold

Charlemagne was crowned “Emperor of the Romans” on Christmas Day, 800. According to some reports, He was completely unaware of the coronation (he had merely shown up at St. Peter’s Basilica for Mass), and did not especially want the title, due to a Frankish understanding of the Romans as an oppressive, pagan people.

9. Holy Roman What?

It’s important to note the wording here. While today most people speak of Charlemagne as the leader of the Holy Roman Empire, no one in his own time would have recognized him as such. The term “Holy Roman Empire” was not actually used until 1254, more than 400 years after Charlemagne’s demise.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. A Tale of Two Cities

Naming Charlemagne “Emperor of the Romans” also had the effect of splitting the waning Roman empire in two, with one Empire ruled by Charlemagne, and another, simultaneous Empire ruled by Empress Irene I in Constantinople. This was a political move on the part of Pope Leo III, who sought to push back against Irene I (who had deposed her son and presumed rightful-heir, Constantine VI), and shift the Roman Empire back toward Western Europe where he might be better protected.

11. Will They, Won’t They

Irene I and Charlemagne’s separate empires had previously been on good terms: one of Charlemagne’s daughters had even been engaged one of Irene’s sons. However, Charlemagne’s coronation caused significant tension between the two “Roman Empires,” tensions which Charlemagne hoped to alleviate by—get this—marrying Irene, and against all odds, she actually said yes! It’s an interesting historical what-if, but the marriage never came to pass: Irene was overthrown in 802, and passed on the following year.

12. Royal Lines

Actor Christopher Lee can trace his family tree back to the Holy Roman Emperor through his mother, an Italian countess.

13. Man’s Best Friend

Charlemagne was accustomed to strange gifts. The Caliph of Abbasid had given him an elephant, which Charlemagne called Abul-Abbas and proudly rode through Germany. According to one account, Charlemagne’s beloved elephant could never get accustomed to the weather in Europe and succumbed to pneumonia.

14. Battle Stories

Charlemagne’s reign was a period of constant conflict, but war was something that he was very, very good at; by the time he passed on, he had conquered nearly all of Europe. His only loss was to the Basques at the Battle of Roncevaux Pass, 778. The story of the battle is retold in the epic French poem Chanson du Roland, as well as the Italian epic Orlando Furioso.

15. Something Fishy

In 778, Charlemagne was in Lourdes, modern-day France, raising arms against the occupying Al-Andulus government. While Charlemagne lay siege to the fortress there, an eagle dropped a trout at the feet of Mirat, the Al-Andulus general, who took it as a sign from God. He surrendered the fort and converted to Christianity, taking the name Lorus, from which we get “Lourdes".

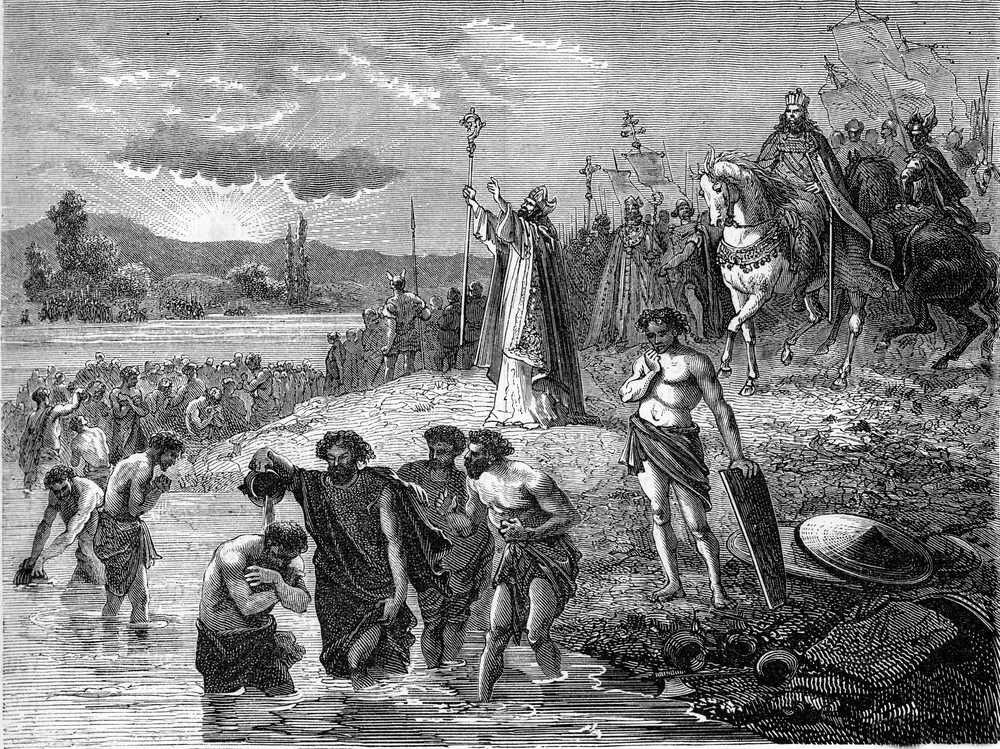

16. Off With Their Heads

Things did not end so peacefully for the pagan Saxons at Verden, in modern day Germany. In 782, Charlemagne had 4,500 of them beheaded for refusing to convert to Christianity.

17. In Memoriam

Nearly 1,200 years later, the Nazis used the Massacre of Verden as an example of Catholic Europe oppressing the German people. In honor of the slaughtered Saxons, a German architect built Sachsenhein, a monument of 4,500 stones that the SS used as a meeting place.

18. Saint Nowhere

Charlemagne is sometimes mistakenly referred to as a saint. While this is not the case (his canonization by Antipope Paschal III in 1165 is not officially recognized), Charlemagne was beatified, which means that he is acknowledged to have entered Heaven and can respond to prayers addressed to him.

19. Renaissance Man

The greatest achievement of Charlemagne’s reign is called the Carolingian Renaissance, a time when political, legal, and academic systems were modernized and universalized across Western Europe. To help him achieve this, Charlemagne invited scholars from as far away as Ireland to his court.

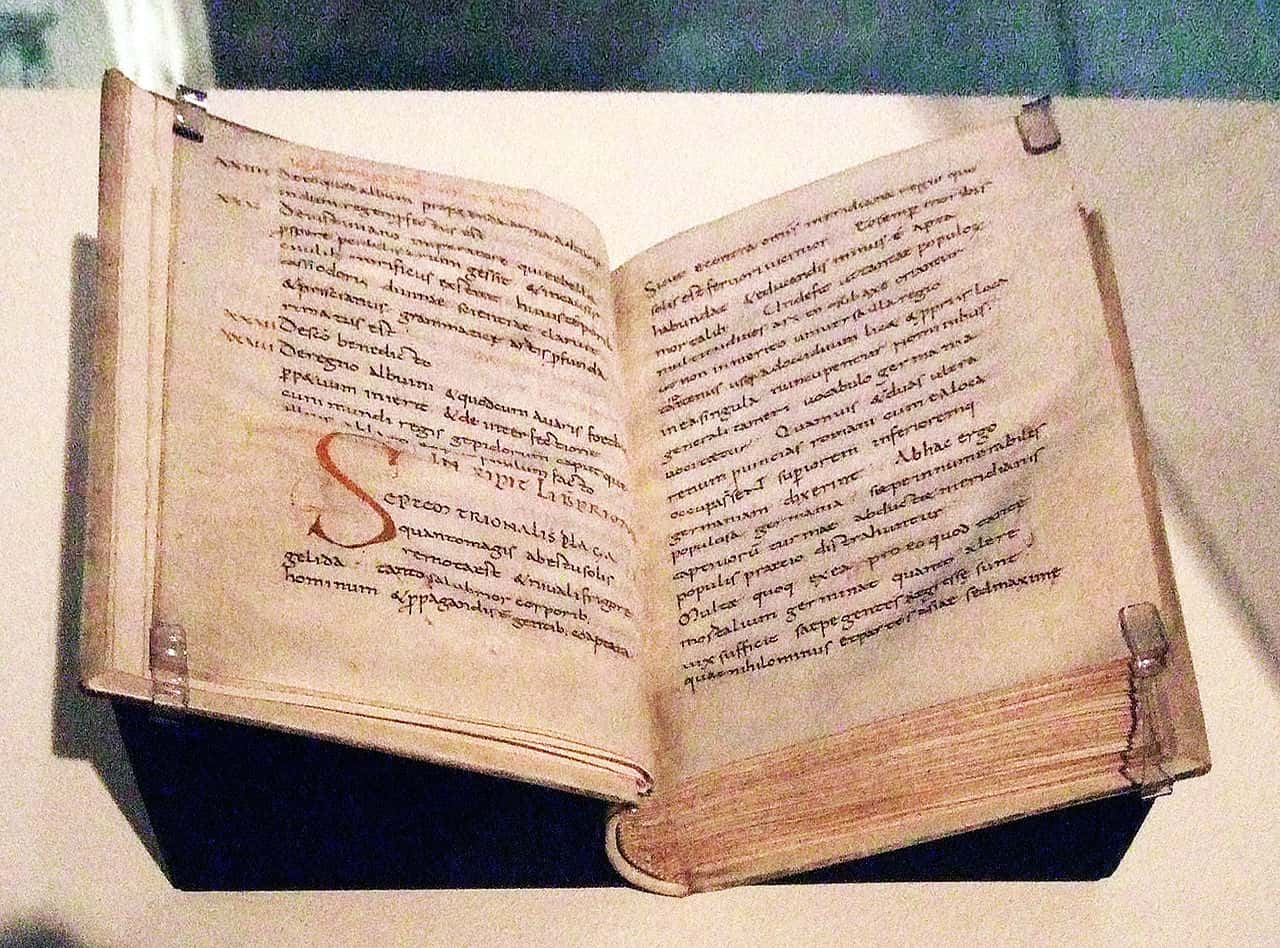

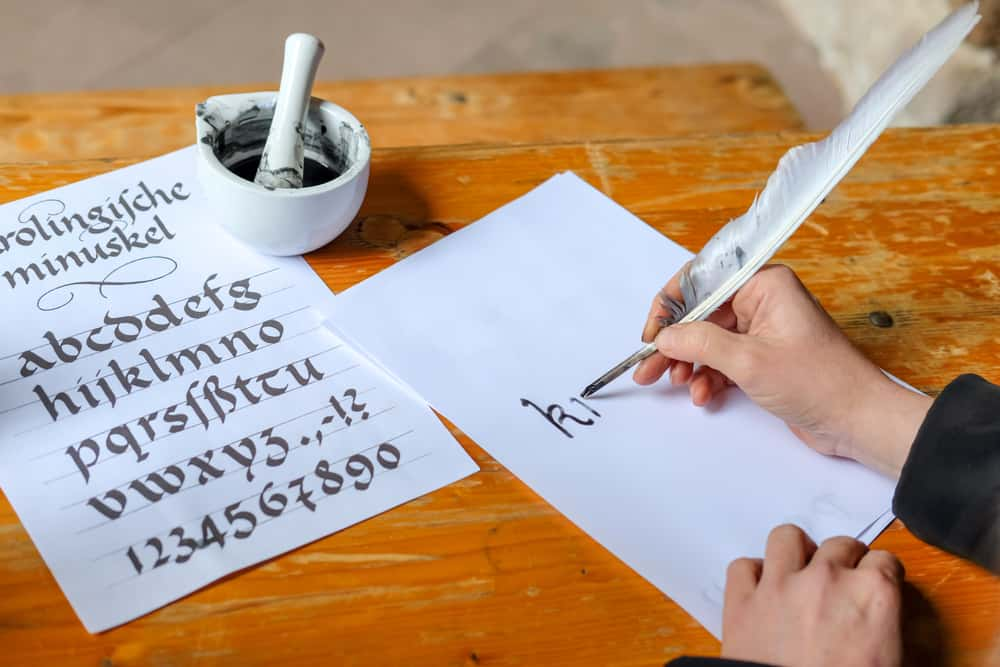

20. Gimme Some Space

Without the Carolingian Renaissance, you probably couldn’t read this list: one of the biggest achievements during this period was the development of a more legible writing system, referred to as “Carolingian minuscule". Carolingian minuscule introduced innovations like the use of lower case letters and spaces between words.

21. Credit Where Credit’s Due

Renaissance scholars thought Carolingian minuscule was so simple and perfect, so distinctly classical, they presumed it had been the style used in Ancient Rome. They adopted and adapted the form for their own writings, abandoning the Gothic scripts which had been in use since the 12th century.

22. Lingua Franca

Latin was established as the standard language of scholarship during this period, allowing the exchange of ideas between the diverse ethnic groups brought together under Charlemagne’s rule. The use of Latin for scientific, religious, and political texts would persist well into the 17th century.

23. One Big, Happy Family

Notable descendants of Charlemagne include all the royal families of Europe, George Washington, Barack Obama, and you, probably. Don’t be so surprised: genealogists say at this point, virtually any European alive in the ninth century will be related to anyone with a drop of European blood today.

24. Pen Pals

While Charlemagne considered Muslims an ideological and political enemy, he recognized that the Muslim world was lightyears ahead of the Franks in math, science, and medicine. Harun al Rashid, the Abbasid Caliph, controlled lands stretching from Iran to Spain. He and Charlemagne maintained a friendly correspondence, which allowed Charlemagne to keep abreast of the latest developments and speed Europe’s technological development.

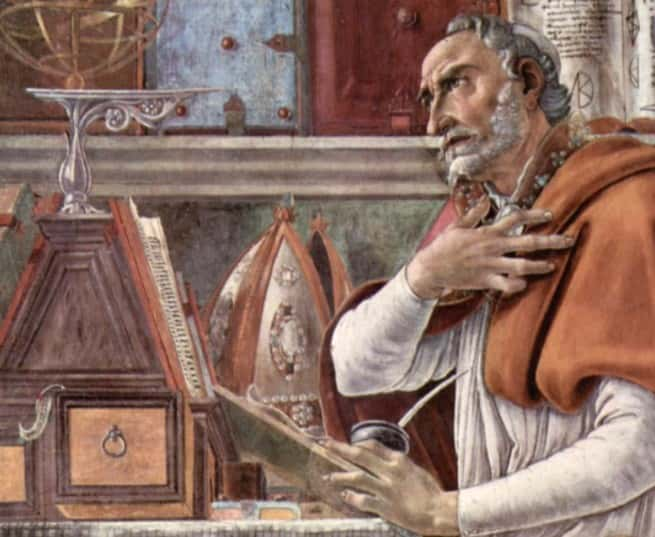

25. Story Time

Charlemagne employed a servant to read to him during dinner. He was especially fond of history and the works of St. Augustine.

26. Witch, Please

Charlemagne was, despite being emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, pretty chill with witches. At the Council of Frankfurt in 794, and at Charlemagne’s insistence, the bishops of the Catholic church denounced the persecution of witches and declared that anyone who tried to burn them would be sentenced to die.

27. Roasts Before Toasts

Charlemagne was a man of temperate habits, not given to feasting or drunkenness. He did have one vice however: roast meat. It was, by far, his favorite dish, and pleas from his doctors to restrict his intake of roast fell on deaf ears.

28. Anti-Fashion

According to his contemporaries, Charlemagne wasn’t the flashiest dresser. He preferred to dress in the style of the average Frankish citizen: a linen tunic and a pair of linen breeches. Think of him as the ninth century’s Steve Jobs: a dude with more money than Croesus who still buys his clothes at Walmart.

29. It's a Bust

The Bust of Charlemagne, a golden statue that today is a part of the treasury at the Cathedral of Aachen, actually contains part of the great emperor's skull.

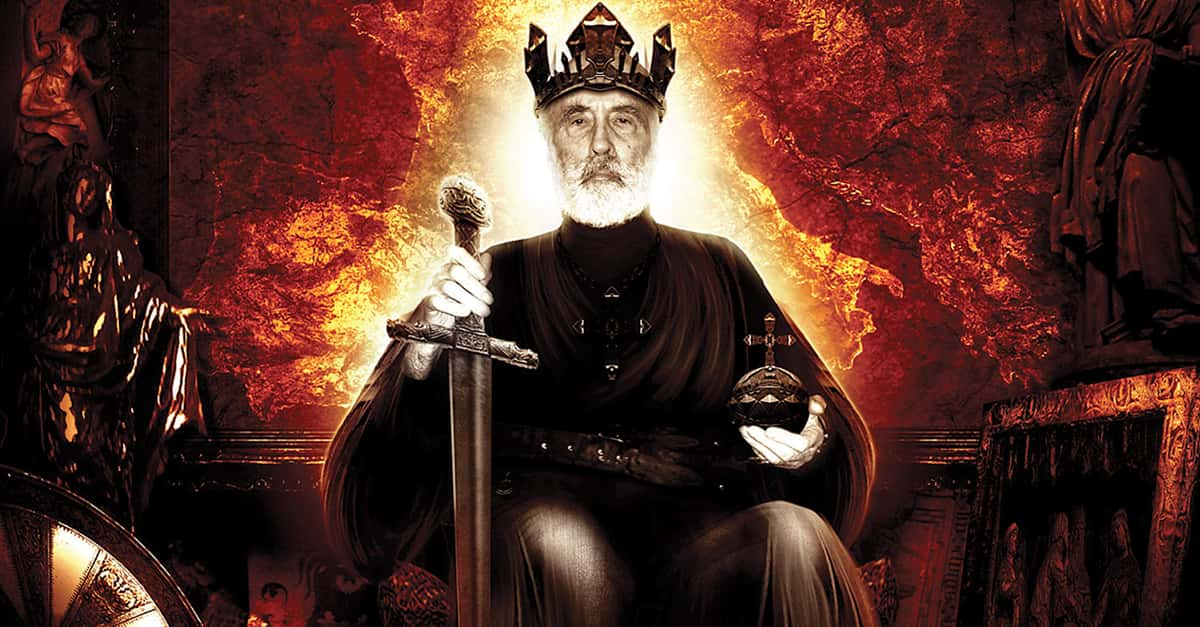

30. Heavy Metal Treatment

In 2010, actor, possible spy, and all-around cool guy Christopher Lee (yes that Christoper Lee, Saruman himself) released a heavy metal concept album based on the life of Charlemagne, entitled Charlemagne: By the Sword and the Cross. Three years later, and on his 91st birthday, Lee released a sequel, Charlemagne: The Omens of Death.

31. Lucky Louis

After his passing, Charlemagne’s empire was to be divided into three equal parts, with each section given to one of his sons Louis, Charles the Younger, and Pepin (the good Pepin—Pepin the Hunchback got nothing). That was the plan anyway. As fate would have it, Charlemagne outlived both Pepins and Charles the Younger, so Louis ended up taking sole possession of the Holy Roman Empire.

32. The Kingdom in Peril

After the demise of Charlemagne, the Carolingian dynasty suffered through insurgencies, rebellions, and power struggles within the family. Under the reign of Charlemagne’s son, Louis the Pious, the empire was divided up into smaller kingdoms ruled by Louis’ sons and nephews, before being reunified, briefly, by Charlemagne’s great-grandson, Charles the Fat.

33. The End of the Empire

Charles the Fat managed to reunify Charlemagne’s empire but now he faced a new enemy: Vikings. Suffering from epilepsy and unable to mount a strong military defense, Charles paid off the Vikings. The strategy worked, but Charles’ subjects nevertheless saw it as a sign of weakness and incompetence. A successful rebellion was mounted against him, and the Carolingian dynasty came to an end, a mere three generations removed from its founder, Charles the Great.

34. All That Work for Nothing

Charlemagne was married four times, and had at least eighteen children. However, only a handful of them outlived him, and his legitimate grandsons numbered only four.

35. An Overprotective Father

Charlemagne did everything he could to prevent his daughters from marrying. Perhaps it was because he was so often divorced and married himself, so he knew firsthand the struggle of married life. Or perhaps he didn’t want a bunch of sons-in-law trying to claim his throne. Whatever the case, none of Charlemagne’s daughters were ever married.

36. They Did Nazi That Coming

The Nazis' traditionally disapproving attitude toward Charlemagne made an abrupt 180 in 1942. Though they had previously cancelled an annual Charlemagne festival in Aachen, the Nazis threw a lavish celebration for Charlemagne’s 1,200th birthday and renamed a division of the SS in his honor. While many found the change in official policy confusing, propogandists had a simple explanation: despite their best efforts, Charlemagne remained popular with the people, and so he would have to be reimagined as a proto-Nazi.

37. Just Pretend

Have you enjoyed these facts so far? Feel like an expert on Charlemagne and the Carolingians yet? Great! Now what if I told you I made it all up? That’s the basis of the Phantom Time Hypothesis, a fringe historical theory that argues that the entire Early Middle Ages—and the rulers who lived during that time—never existed. Like, whoooaa man...

38. Out of Time

According to Heribert Illig, a German historical revisionist, Holy Roman Emperor Otto III, with the help of Pope Sylvester, fabricated the entire early Medieval period. Illig argues that Otto III wanted to place himself in the theologically significant year 1000 CE, instead of the eighth century when he actually ruled, so he and Pope Sylvester cooked up about 240 years of history, including the character Charlemagne. Of course the major flaw with this theory is that it totally ignores what was going on everywhere outside of Europe during the eighth and ninth centuries. Still, woooaa...

39. Rebelling Against His Parents

In 792, Charlemagne’s eldest son, Pepin the Hunchback, launched a rebellion against his father with the help of some Frankish noblemen. When the plot was exposed, Pepin’s conspirators were sentenced to die (though some were later released), and Pepin himself was exiled to the monastery in Prüm, where he would later die of plague.

40. That's Cold

Pepin’s anger at his father might well have been justified, as it seems that Charlemagne had no intention of leaving his kingdom to his eldest son. Charlemagne had divorced Pepin’s mother, Himiltrude, and married Hildegard, leaving Pepin’s legitimacy in doubt. In a telling move, Charlemagne had his and Hildegard’s son (and Pepin’s half-brother) Carloman renamed Pepin. So maybe Pepin can be forgiven for feeling like he was being replaced.

41. For the Man Who Has Everything

In return for crowning him Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne gave Pope Leo III an unusual thank you gift: the supposed prepuce of Jesus Christ, known as the Holy Prepuce, which Charlemagne claimed had been delivered to him by an angel.

42. You Can’t Teach an Old Dog New Tricks

Despite his commitment to the advancement of literacy during his reign, Charlemagne never learned to read or write himself. This was not for lack of trying: one tutor noted that Charlemagne kept a tablet under his pillow so he could practice writing late at night. His lack of success, the tutor reckoned, was because Charlemagne was too old when he started trying to learn.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26