An Eerie Story With A Life Of Its Own

Though the smoke and chaos of the Battle of Mons are gone, mystery still surrounds the famous WWI battle. Stories spread throughout Britain about ghostly archers who helped stave off the onrushing Germans. Later it was said that angels had delivered the British forces safely from the field to live another day. But where did the story of the Angels of Mons come from?

Outbreak

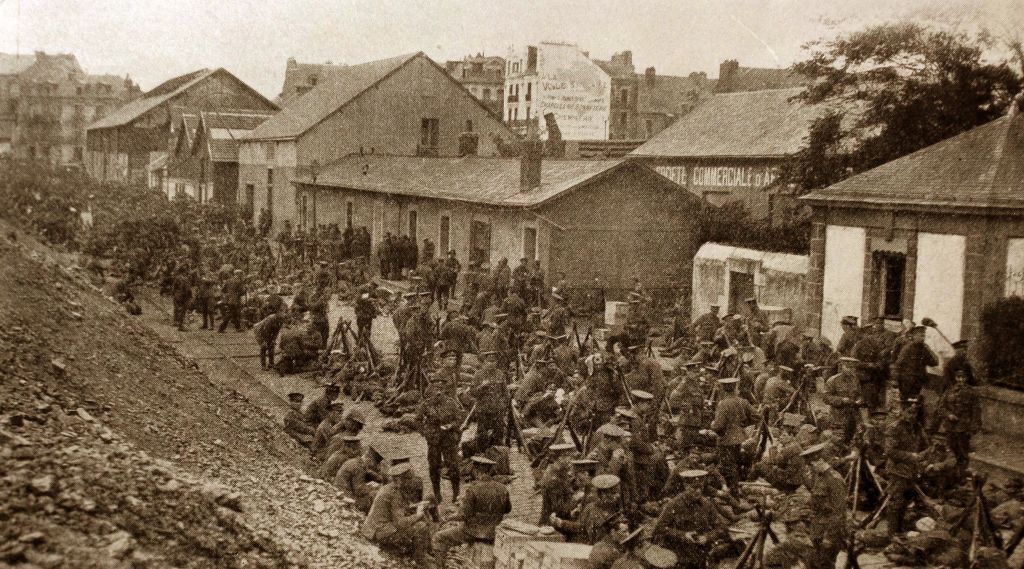

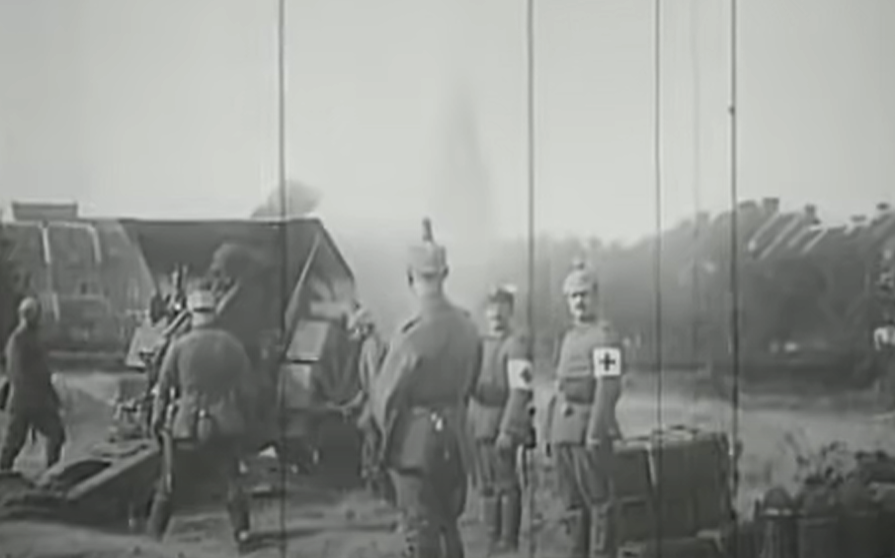

The August 1914 outbreak of WWI involved almost all the major countries of Europe. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) had arrived to reinforce their French allies as the Germans launched a massive invasion through Belgium, driving on Paris. As the Germans advanced across Belgium, it looked like nothing could stop them.

Italian Army Photographers 1915-1918, CC BY 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

Italian Army Photographers 1915-1918, CC BY 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

Desperate Stand

On August 23, 1914, in an attempt to stem the German onslaught, the BEF took up a position near the southern Belgian town of Mons, close to the French border. Along the banks of a canal, the British prepared to make a stand against the oncoming Germans.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Clash At Mons

The Germans arrived at Mons, and over a long day of battle, neither side would give way. Despite heavy casualties, the Germans continued to press forward. In the late afternoon, with heavy losses of their own, the news of the withdrawal of the neighboring French forces caused the British commander to order a retreat.

Retreat

As the exhausted British units pulled back toward Paris, the mood in the ranks was high. In their first major battle, though they’d failed to stop the German flood, they had still proven their mettle. Vastly outnumbered, they fought coolly and effectively. There was reason to believe they could still turn the tide.

Ryry33, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ryry33, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

News Of A Great Battle

The news of the Battle of Mons was met with great excitement by the British public. Eager to find out what was happening, people devoured newspaper updates on the situation. As the struggle continued through September 1914, journalists gripped readers’ attention with their dramatic accounts of the action.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Staying On Top Of The Story

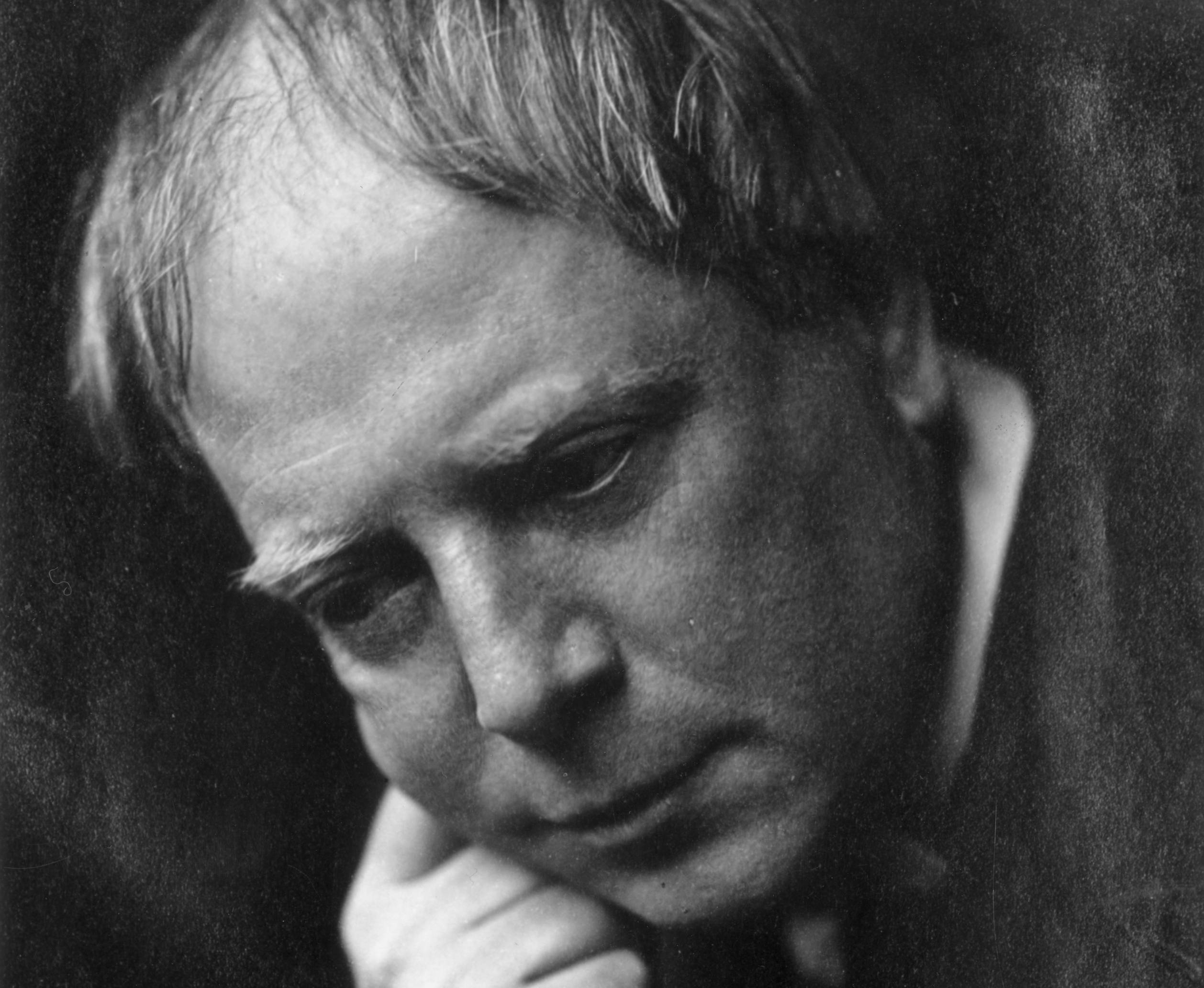

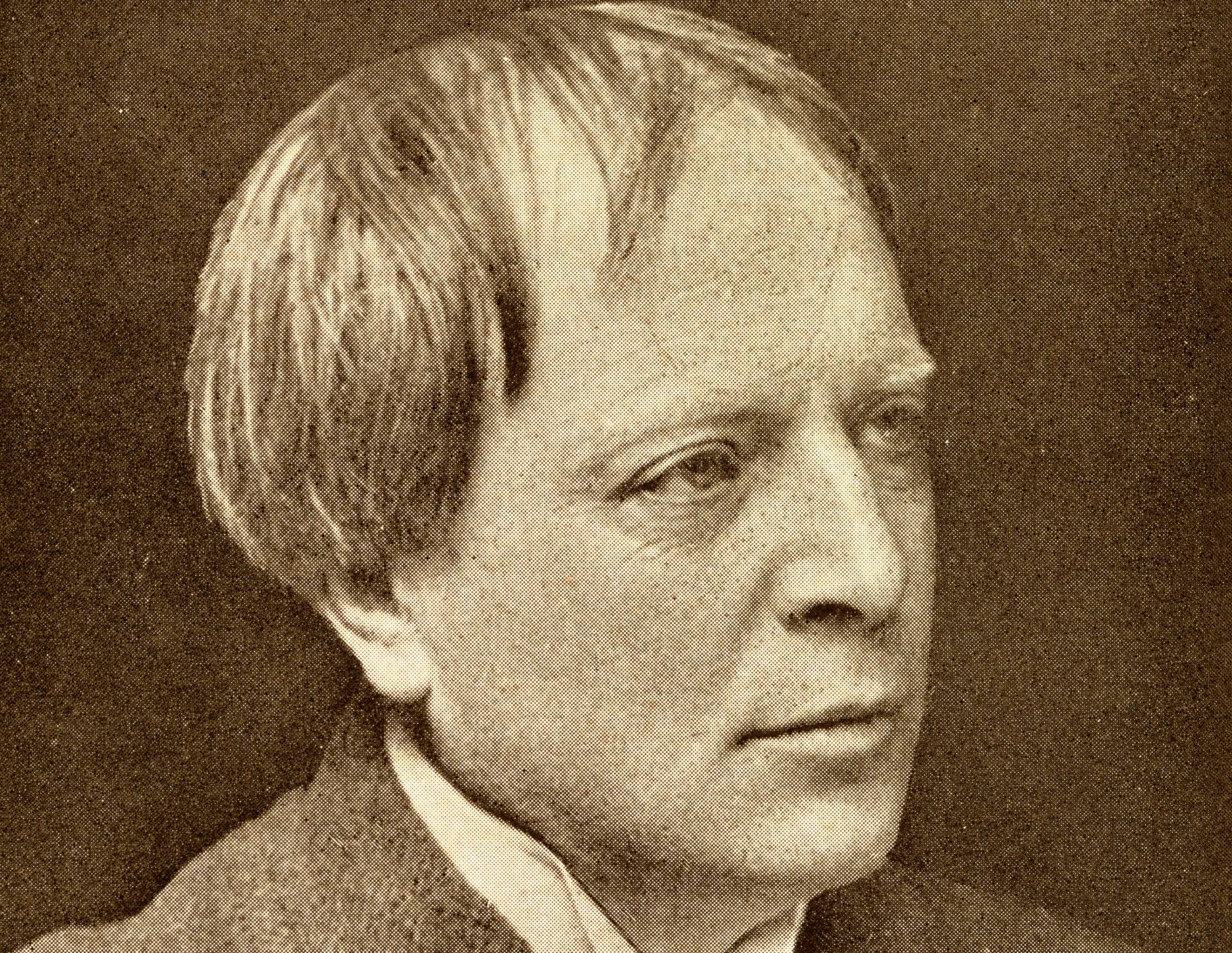

One of the journalists navigating this swirling information environment was Arthur Machen. Working for The Evening News, Machen had written several stories about the unfolding crisis at the front.

Then, in the aftermath of the British retreat from Mons, Machen read with horror about the harrowing ordeal the British forces endured in the battle.

A Vision Seared In The Mind

Machen imagined the young men at Mons surrounded by fire and terrible suffering. Tormented by these vivid thoughts, he attended a Sunday morning church service. The church sermon combined with his impressions of the Mons battle to form a powerful visual and spiritual image in his mind.

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

A New Tale To Tell

Deeply affected by his reading on the Mons battle, Machen set to work on a series of fiction stories about the action. Machen drew on several sources to add color to the stories. Rudyard Kipling, the Battle of Agincourt, and a warrior’s feast in the afterlife were just some of the sources he used to embellish his tales.

Yes, as a journalist, Machen was a bit of an odd duck.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

No Ordinary Storyteller

Machen had abandoned a career as a fiction writer, but not before earning praise—and fierce criticism—for his novella The Great God Pan in 1895. While the controversial content of his horror story scandalized mainstream critics, later authors, including Stephen King, praised the work’s originality.

If nothing else, it showed that Machen was a gifted storyteller.

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

Everett Collection, Shutterstock

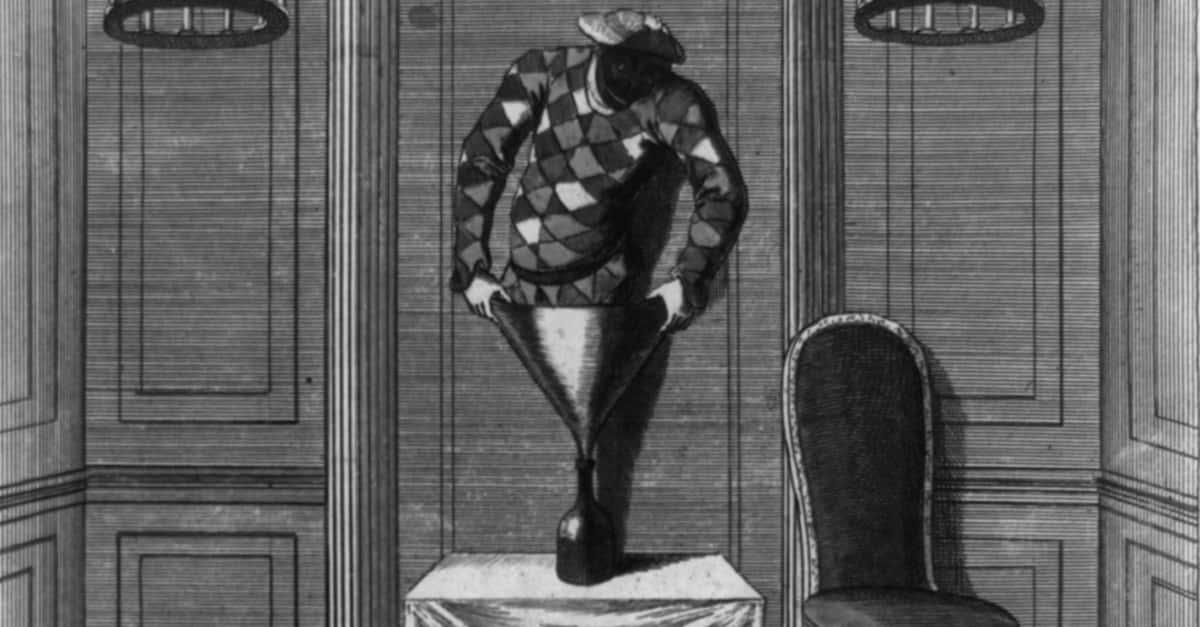

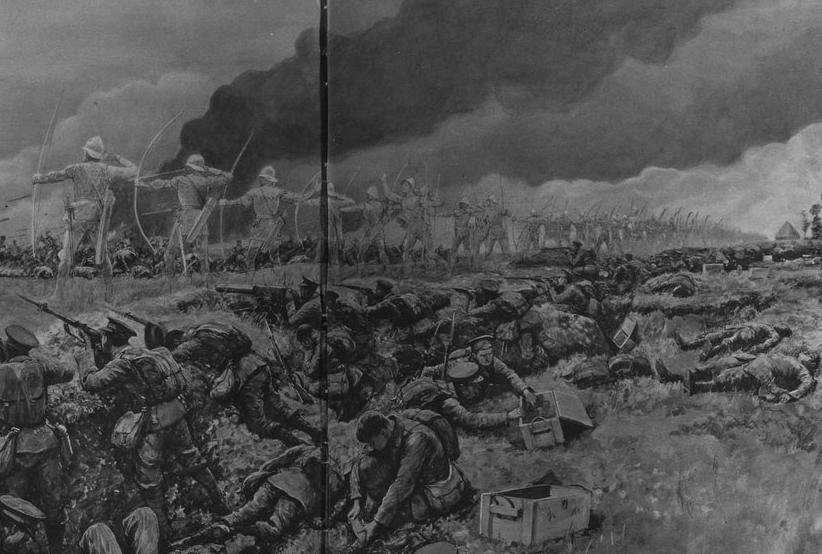

The Bowmen

One of Machen’s stories about the Mons battle was called The Bowmen. Emulating a dispatch from the front, and mentioning the “authority of the Censorship” to give the story a ring of authenticity, Machen gave a riveting—and entirely fictional—account of the battle.

After Amédée Forestier, Wikimedia Commons

After Amédée Forestier, Wikimedia Commons

Shining

The key moment in the story concerns a British officer under heavy fire. Recalling the image of St George he had seen printed on a dinner plate in a pub where he’d once eaten, the beleaguered man shouts to summon St George.

At that point a host of shapes or figures appear—ghosts of the English archers of the 1415 Battle of Agincourt— and ultimately ward off the German advance. Crucially, Machen described the bowmen as having a "shining" about them.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Day Like Any Other

Machen regarded The Bowmen as one of the more mediocre of the stories he had penned about the Mons battle. After submitting the piece to his editor on the afternoon of September 29, 1914, he quickly turned to other matters. But there was something peculiar about this particular tale.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Was It Fact Or Fiction?

A strange thing occurred in that night’s edition of The Evening News. Though Machen had written The Bowmen as a work of fiction and specified as such to the editor, the piece was printed alongside the day’s other news stories without any indication that it was not, in fact, a real news story.

Readers began to take a closer look at the unusual story.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Strange Question

A few days after The Bowmen’s publication, Machen got a letter from the editor of Occult Review asking for evidence on the facts of his story. Machen replied flatly that the story was entirely made up. Days later the editor of Light wrote to Machen with similar questions.

Replying firmly that the story was fiction, Machen thought he’d squelched any chance of false stories developing. But that thought turned out to be premature.

Historical Picture Archive, Getty Images

Historical Picture Archive, Getty Images

Request For Reprints

A couple of months later Machen received several letters from parish magazines (church bulletins) requesting permission to reprint The Bowmen. The editor of The Evening News, pleased that the story had touched a chord with readers, gave the go-ahead. The reprints would surely put to rest the public’s curiosity—or would they?

The Fascination Continues

In the spring of 1915 Machen received another letter from a parish magazine editor claiming that their February edition carrying The Bowmen had completely sold out and that hordes more readers in the community were eagerly looking to get their hands on a copy. The magazine editor asked if they could reprint the story as a pamphlet with a special preface by Machen. The answer wasn’t long in coming.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Priestly Suggestion

Machen quickly gave his permission to the churchman to reprint the story, but told them he couldn’t be bothered to write a preface since the story wasn’t true. To Machen’s consternation, the priest wrote back to suggest that it was impossible that the story wasn’t true since his entire congregation believed in it word-for-word.

The surprised Machen was struck by a realization.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Snowballing Rumors

It now dawned on Machen that the requests for reprints were not just for the simple enjoyment of a dramatic tale from the frontlines. The public believed deeply that a great spiritual and religious event had occurred at Mons to deliver the British army from certain doom. But what had triggered that belief?

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Mesmerizing Image

Aside from the rich detail of Machen’s story, the brief description of the figures as “shining” as they appeared between the opposing armies convinced people that angels had interceded to save the British. Machen’s inventive detail of a young officer seeing an image of St George in a British pub was a textural element that only added to the story’s power.

Also breathing life into the story was the horror of the Western Front.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Growing Conflict

By the spring of 1915 the national optimism of the previous summer had evaporated. The belief that the conflict would be over by Christmas had proven hollow as mounting casualty lists brought home the reality of the situation. The public mood darkened as grim news reports continued to roll in.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Litany Of Bad News

In the spring of 1915, bad news was legion in Great Britain. Failed offensives on the Western Front and in Turkey, the sinking of the liner Lusitania, and the use of chlorine gas by the Germans were only a few of the horrors to shock the British public. Amid all the uncertainty, rumors flourished.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Rumors Bloom

The Angels of Mons wasn’t the only rumor circulating. Other accounts told of crucified servicemen left out in No Man’s Land and ghostly German officers appearing in the trenches. Skepticism of the heavily-censored press and a rich culture of storytelling by men trying to relieve the monotony of life in the trenches were important factors in the spread of such tales. The rumors inevitably started to make their way into print.

The Occult Review

Author AP Sinnett, writing in the May 1915 issue of The Occult Review, claimed that the men at Mons could see “a row of shining beings between the two armies”. Machen read the fanciful tale; realizing what its source material had been, he decided it was high time to set the story straight.

And make a little dough while he was at it.

Setting The Record Straight

In August 1915, Machen published all of his Mons stories in a new anthology titled The Bowmen and Other Legends of the War, which quickly became a bestseller. In a long introduction, he described in detail The Bowmen’s origin and its surprising impact, and claimed that it was the source for Sinnett’s Occult Review article.

But Machen’s explanation only stirred up a hornet’s nest of opposition.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Rock-Ribbed Believer

Author Harold Begbie was one of those not amused by Machen’s assertion that the shining angels existed only in readers’ (and writers’) heads. No slouch as a writer himself, Begbie released his book On the Side of the Angels that included several unsourced accounts of the apparitions with chapters railing against Machen.

While the two authors butted heads, a flood of other reading material was appearing.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Phyllis Campbell

Phyllis Campbell, a nurse who had treated wounded men on the Western Front released a memoir in 1915 called Back to the Front: Experiences of a Nurse. She recounted the visions experienced by men at the front who claimed to have seen Joan of Arc and the archangel Michael.

Aussie~mobs, Wikimedia Commons

Aussie~mobs, Wikimedia Commons

A Religious Epic

Meanwhile, a Scottish minister named Dugald MacEchern had created a 160-line epic poem entitled “The Angels of Mons”. Uninterested in arguing the facts of the matter, MacEchern’s poem used intense holy imagery to express the unshakable courage and righteousness of the British people.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Cultural Phenomenon

By summer of 1915, the Angels of Mons story had spread to all corners of Britain. Machen’s attempt to explain the truth of the matter had been futile, as the account was told and retold in countless newspapers and church sermons.

Belief in the mysterious shining beings was even seen as a litmus test of loyalty to the nation. Even so, the story had its share of skeptics.

Research Society Wades In

The buzz of angel-related stories circulating through Britain that year attracted the attention of the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), which carried out a full investigation of the story.

The Society found that the overwhelming majority of the stories were second-hand accounts, and concluded that the Angels of Mons story was unfounded. And the Society weren’t the only ones to go against the narrative.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Veterans’ Stories Don’t Fit

Later investigations found that the only reliable documented instances of witnesses claiming to see visions came after the end of the Battle of Mons. At that time the British were in retreat, utterly drained after their ordeal; under such strain it wouldn’t be surprising to experience hallucinations.

But even those didn't add up; Instead of archers or shining beings, the men said they had seen cavalrymen. And those weren’t the only problems with the story.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Narrative Gap

Not only were there problems with the conflicting details of the veterans’ accounts, but another question arises with respect to the timing of the rumors: Why were there so many stories circulating about the angels in the spring of 1915 when there had been little talk of them over the course of the fall and winter of 1914–15?

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Propaganda Campaign?

The British public had been rocked by one disastrous setback after another in the spring of 1915. Had the government aided in planting or spreading the stories in an effort to bolster the peoples’ faith in the cause? This would explain the sudden explosion of stories about the angels eight months after the battle had ended.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

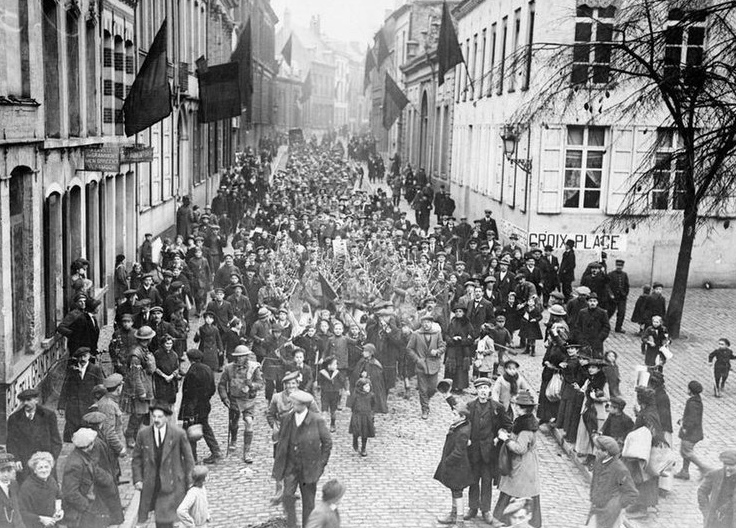

The Conflict Ends

On November 11, 1918, the news arrived at the front that an armistice had been signed. An outpouring of joy—and relief—swept through the ranks. The Canadian forces received the news while they were in the town of Mons, which they had captured only hours before.

The struggle ended near where it began, at the scene of one of its greatest legends.

Rider-Rider, W (Lt), Wikimedia Commons

Rider-Rider, W (Lt), Wikimedia Commons

Unreliable Memories

With WWI finally over, the participants began the task of writing its history. One such fellow was Brigadier-General John Charteris, who wrote in 1931 that an angel of God had wielded a flaming sword to block the German advance at Mons. But a check of his 1914 diaries revealed that he made no mention of such an event at the time.

The old story still had a hold on the British imagination.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

A Suggestible Public

History suggests that great disasters or shocking events make people more receptive to the existence of the supernatural. In a time of great uncertainty, the story of guardian angels on the frontlines came as a comfort to a worried population back home. This was how the Angels of Mons wove a spell on the British public.

But the legend’s influence still echoes even today.

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Cromwell Productions, Line of Fire (2002)

Fodder For A New Age

The public fascination with angels and other divine phenomena has waxed and waned over the decades. The 70s and 80s saw a resurgence of interest in the Angels of Mons stories—and angels in general—by Christians and practitioners of New Age philosophies.

Skeptics and science defenders have been equally vocal in refuting the stories. But some storytellers can be very convincing.

David Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

David Dixon, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Evidence Found

In 2001, a man claimed to have dug up conclusive photo evidence of the Angels of Mons in the personal effects of a WWI veteran named William Doidge. The treasure trove consisted of a diary and film footage collected by Danny Sullivan in a British junk shop.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Hoax Admitted

After generating excitement in the press and even rumors of a movie deal, Sullivan admitted he had made up the entire scenario to drum up interest in the nearby Woodchester Mansion tourist attraction.

Though it turned out to be a hoax, the incident showed there was still much public interest in the Angels of Mons.

Acardillo21, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Acardillo21, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Continued Fascination

The legend of the Angels of Mons served its purpose in 1915 by strengthening the faith of a worried nation. Today a steady stream of books, articles, podcasts and videos still discuss the phenomenon and its origins. And still lingering in the background is that masterful old scribe and storyteller, Arthur Machen.

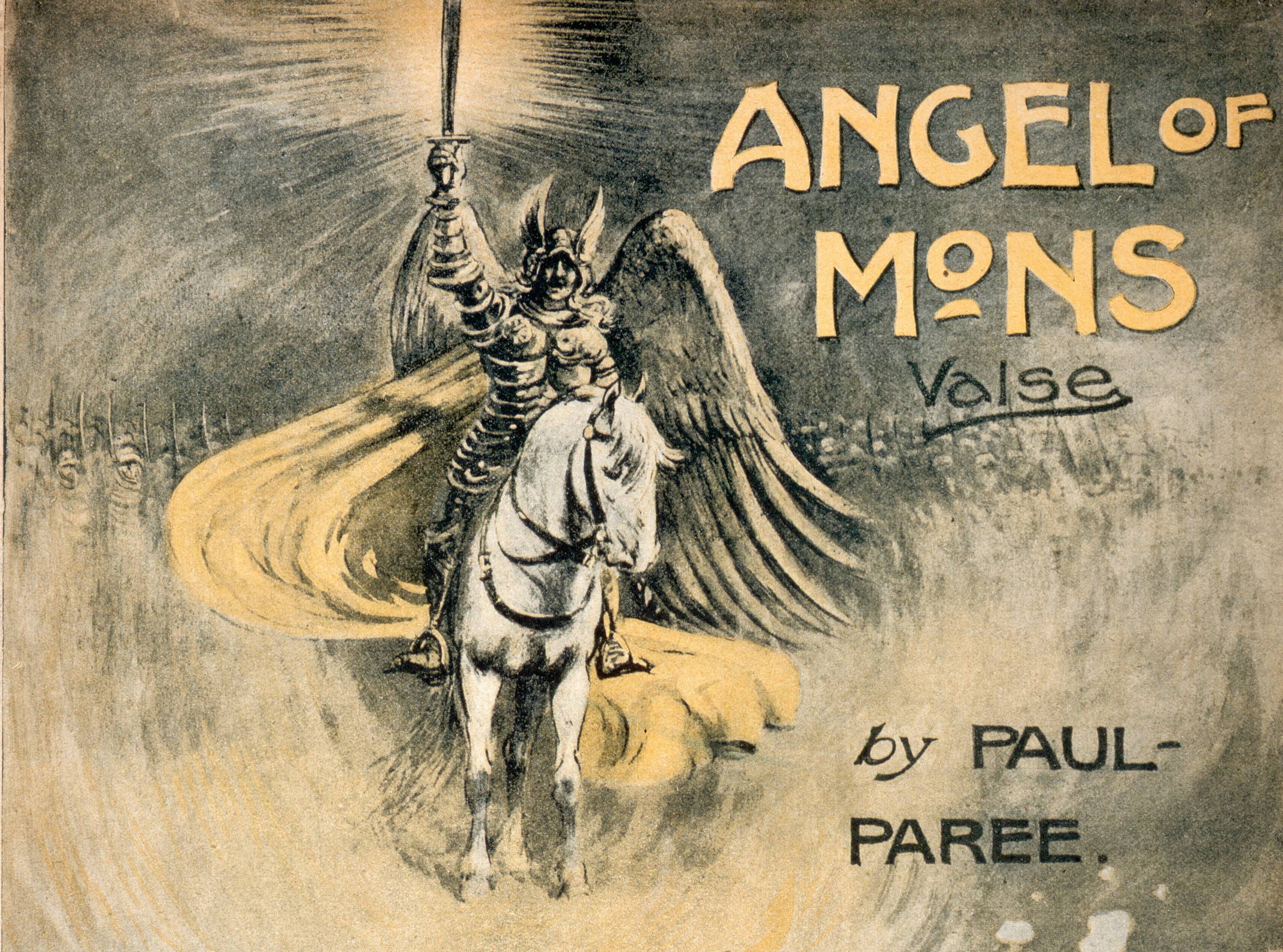

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons