P. Pfarr NLD, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

P. Pfarr NLD, CC BY-SA 3.0 DE, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

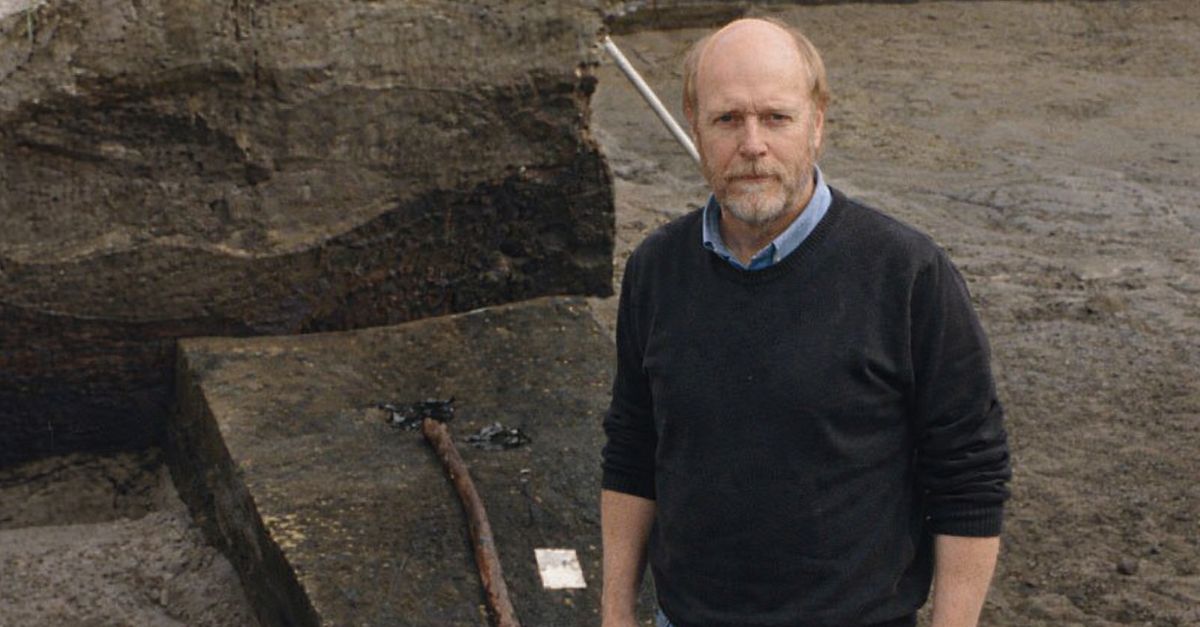

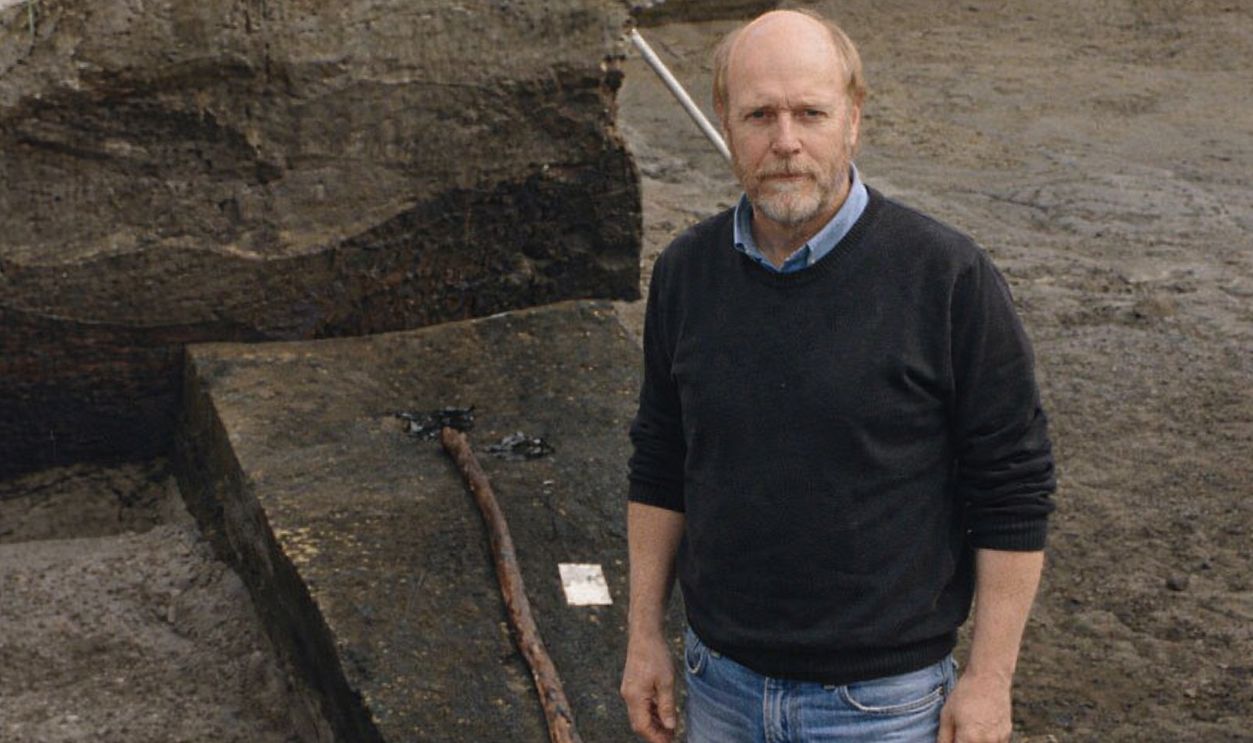

For decades, the Schoningen spears held pride of place as the world's oldest hunting weapons. Eight wooden javelins, pulled from an ancient lakeshore in northern Germany during the 1990s, seemed to prove that early humans were crafting sophisticated weaponry 300,000 years ago. The timeline made sense. The location sat in geological layers that fit neatly with Homo heidelbergensis, our probable ancestors who roamed Europe during that era. Museums displayed them as evidence of Heidelbergensis ingenuity. Textbooks cited them as proof of advanced cognition emerging in pre-Neanderthal populations. Then scientists took another look at the dates, and everything changed. New analysis pushed the age forward by roughly 100,000 years, landing the spears squarely at 200,000 years old. That adjustment might sound minor, but it completely flipped the narrative. At 200,000 years, these weapons weren't made by Homo heidelbergensis at all.

Redating The Evidence

The original age estimates relied on geological context and comparisons with animal fossils found in the same sediment layers. Those methods worked well enough for rough timelines, but they left room for interpretation. When researchers reexamined the site more carefully, they focused on the specific stratigraphic position and the associated faunal remains. The updated analysis showed that the layers containing the spears were younger than initially thought. A better understanding of the site's complex geology and more refined comparisons with other dated European sites helped narrow the timeframe. The revised chronology placed spear-making activity at approximately 200,000 years before present, a significant shift from the earlier estimate of 300,000 years. That timeframe coincides with the early presence of Neanderthals in Europe, not their predecessors.

P. Pfarr NLD, Wikimedia Commons

P. Pfarr NLD, Wikimedia Commons

What This Means For Neanderthals

The Schoningen spears aren't crude stabbing sticks. Each one measures between six and seven feet long, carefully carved and weighted for throwing at a distance. Experimental archaeology has shown that these designs work remarkably well. Modern replicas can pierce animal hide at ranges exceeding 20 meters when thrown by someone with decent technique. That level of performance requires planning, not just brute strength. Neanderthals had to select appropriate wood, season it properly, shape it with precision tools, and test the balance. They needed to understand how prey animals move, where to position themselves for ambush, and how to coordinate group efforts during hunts. The 200,000-year date means Neanderthals were doing all of this at least 100,000 years earlier than previously credited. The implications extend beyond hunting technology itself. Complex wooden tools require forward thinking, abstract reasoning, and probably some form of knowledge transfer between generations. You don't accidentally invent a balanced javelin. Someone had to experiment, fail, adjust, and eventually teach others the successful method. That's culture. That's accumulated knowledge. The spears become evidence of Neanderthal cognitive sophistication that rivals anything attributed to early Homo sapiens during the same period. We've spent generations underestimating them, and a single redating project just demolished decades of assumptions.

Rewriting The Timeline

Well, this discovery forces a major reset in how we map human technological evolution. If Neanderthals were crafting advanced hunting weapons 200,000 years ago, they were developing complex tool traditions in parallel with early modern humans in Africa. The old narrative positioned Homo heidelbergensis as the innovative species that laid the groundwork for later human advancement, with Neanderthals as an evolutionary dead end that contributed little. The Schoningen evidence flips that script entirely. Neanderthals were innovative engineers who solved survival challenges with remarkable ingenuity. The updated timeline also raises questions about whether similar technologies existed even earlier, waiting to be discovered in sites not yet excavated or properly dated. Wooden artifacts rarely survive the archaeological record. The Schoningen spears were only preserved because they fell into oxygen-poor, waterlogged sediments that prevented decay. How many other Neanderthal innovations have rotted away, leaving us with incomplete pictures of their capabilities? The 200,000-year-old spears might represent the visible tip of a much larger technological tradition that we've simply never been able to document. Every redating project like this one reminds us that prehistory isn't settled science. It's constantly being revised.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons