Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Sailko, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Long before Rome claimed authority over the Italian peninsula, the Etruscans shaped a culture grounded in ritual practice and visual expression. Their cities prospered through trade and craft, yet much of what remains comes from how they approached death. Burial was not treated as a separation. Instead, it marked continuity shaped through architecture and imagery. Archaeologists have documented rare painted chambers in Cerveteri’s necropolis where pigments survive in protected spaces sealed by earth layers for centuries. Color still clings to its walls, preserved beneath layers of earth that sealed the space for centuries. Such survival remains uncommon, especially at a site where most decoration has faded beyond recognition. This article examines the Etruscan world surrounding the discovery, describes the painted chamber in detail, and explains why it matters. Each section builds toward a clearer understanding of belief, memory, and how ancient Italians imagined life beyond death.

The Etruscans and Cerveteri’s Necropolis

The Etruscans rose to prominence in central Italy between the ninth and fourth centuries BCE. Their society lacked political unity yet shared religious customs, artistic styles, and economic ties. Trade also connected their cities to Greece and the wider Mediterranean, allowing ideas to circulate alongside goods. Cerveteri, known in antiquity as Caere, ranked among the most influential Etruscan city-states. Its location supported both maritime exchange and inland access, which helped generate sustained wealth. That prosperity extended into burial practice, where tombs became expressions of identity rather than simple markers of death.

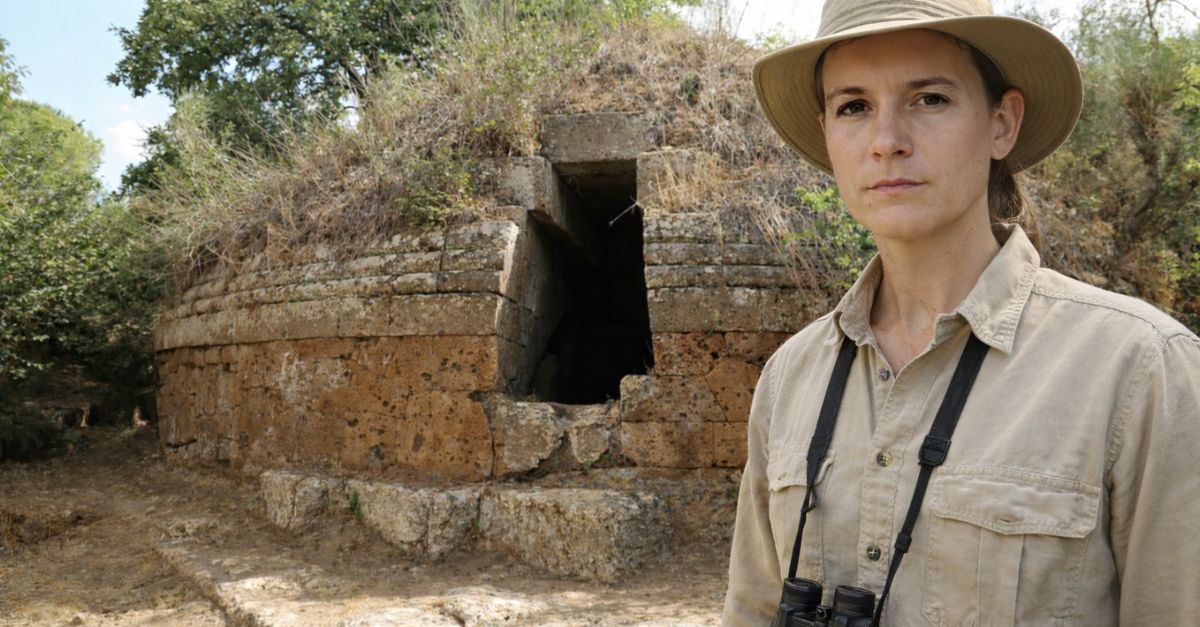

The Banditaccia necropolis further covers a wide expanse carved directly into soft tufa rock. Tombs line winding paths, arranged in clusters that resemble planned neighborhoods. Walking through the necropolis feels closer to moving through a silent town than a cemetery. Many tombs replicate domestic interiors. Carved ceilings imitate wooden beams, while stone partitions divide rooms as they would in a home. These choices reflect a belief that existence continued beyond death in familiar surroundings. The afterlife was not imagined as distant or abstract. It remained grounded in daily experience. Painted tombs remain rare at Cerveteri. Most decoration has disappeared due to moisture, collapse, or time itself. As a result, any chamber retaining pigment offers rare insight into how Etruscans used color to reinforce belief. This scarcity makes the newly discovered chamber especially valuable.

The Painted Chamber and Its Symbolism

Painted chambers at Cerveteri survive only in limited and fragmentary form, with most decoration long faded or lost. Where traces remain, muted reds and earth tones appear on prepared surfaces, suggesting careful planning. Unlike Tarquinia, imagery here emphasized architectural form over vivid narrative painting. Imagery within the chamber suggests ritual activity tied to communal life. Scenes associated with gatherings imply continuity rather than mourning. The deceased appears integrated within shared custom, not isolated from it. This approach aligns with broader Etruscan funerary traditions that emphasize participation instead of loss.

Painting required familiarity with mineral pigments and surface preparation. Artists needed to understand timing, adhesion, and durability. The execution demonstrates confidence and control, challenging older assumptions that Etruscan painting lacked the sophistication of later Roman examples. Symbolically, the chamber reinforces belonging. Ritual imagery connects the deceased to collective practice, while the structured layout imposes order. Nothing suggests chaos or fear. Instead, the environment communicates reassurance. Death becomes another phase within an established system shaped by belief and repetition. The placement of imagery also matters. Scenes occupy walls at eye level, encouraging engagement rather than passive observation. The chamber functions as a space meant to be entered and experienced, not simply sealed and forgotten. Through this design, the tomb maintains its presence long after burial.

Cultural and Archaeological Significance

The painted chamber offers rare, direct insight into Etruscan ritual life and belief systems. It shows how meaning shaped artistic decisions and how identity extended beyond death. In a culture with limited surviving written records, visual evidence carries unusual weight. Preserved pigments also add scientific value. Chemical analysis reveals sourcing, preparation methods, and trade connections across ancient Italy, helping scholars trace artistic exchange during a period that predates Roman dominance and reshaped regional influence.

The discovery reinforces Cerveteri’s role as a vital center for cultural education and archaeological study. Each find deepens public understanding of a civilization often reduced to a prelude to Rome. The chamber challenges that framing, showing influence as layered and continuous rather than erased. Through its imagery, Etruscan belief remains active in the present. Stone and pigment still communicate intention, memory, and care, sharpening historical understanding rather than overturning it.