Not Just Satellites

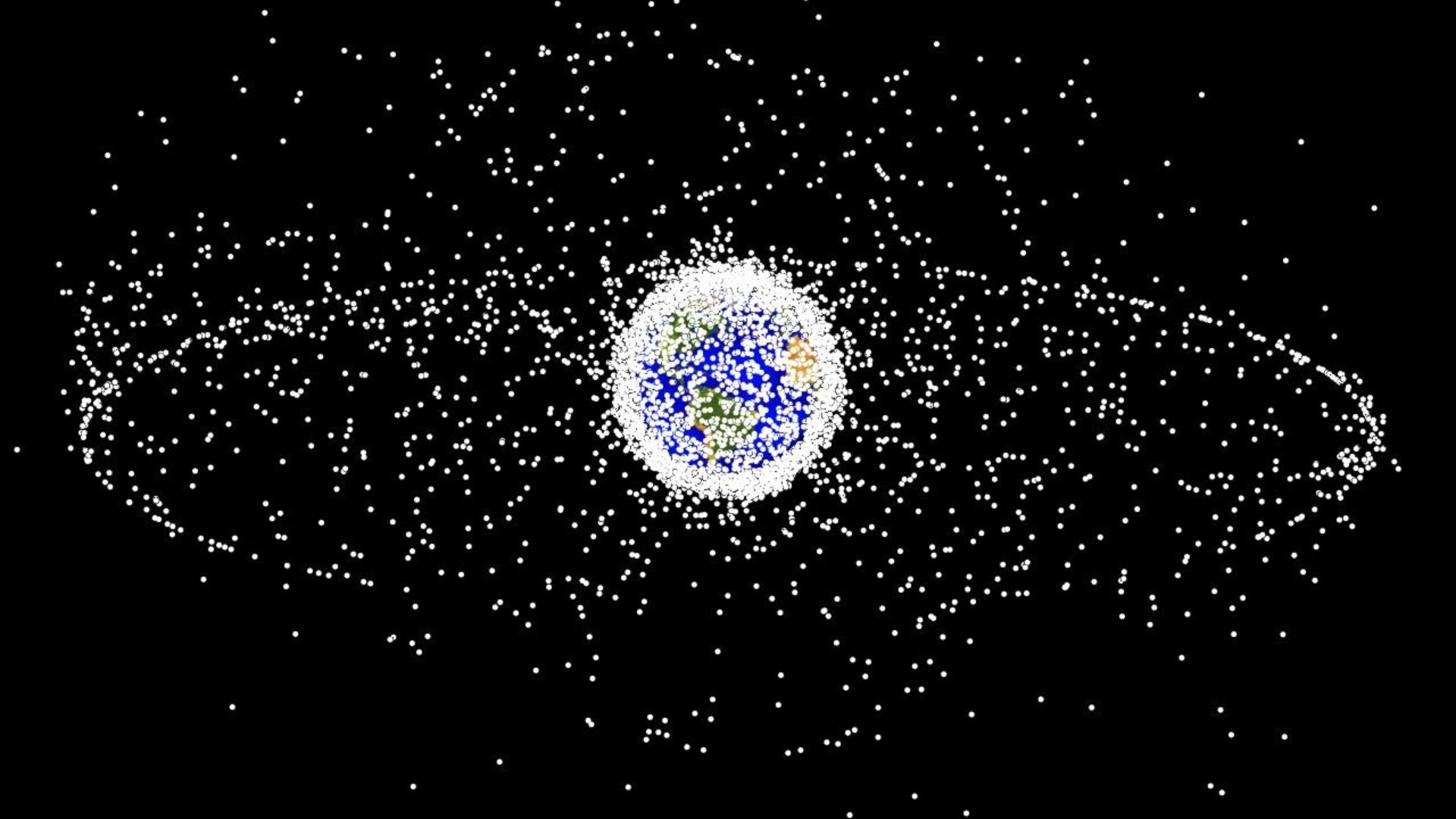

Space might seem endless, yet every launch leaves something behind. Not all of it is useful. Some pieces are ordinary, some unexpected, and each one quietly joins the strange crowd circling the Earth.

Defunct Satellites

Right now, there are about 3,000 dead satellites silently drifting through space like cosmic zombies. These technological corpses vastly outnumber the roughly 11,000 operational satellites currently beaming down your Netflix streams and GPS coordinates. But what makes a satellite "defunct"?

Defunct Satellites (Cont.)

Sometimes it's a simple battery failure, sometimes a critical component burns out, and occasionally they just run out of fuel. The European Space Agency's Envisat, weighing 8.2 tons, has been tumbling uncontrollably since 2012 despite costing over $2.9 billion.

Envisat: 20 years after launch by European Space Agency, ESA

Envisat: 20 years after launch by European Space Agency, ESA

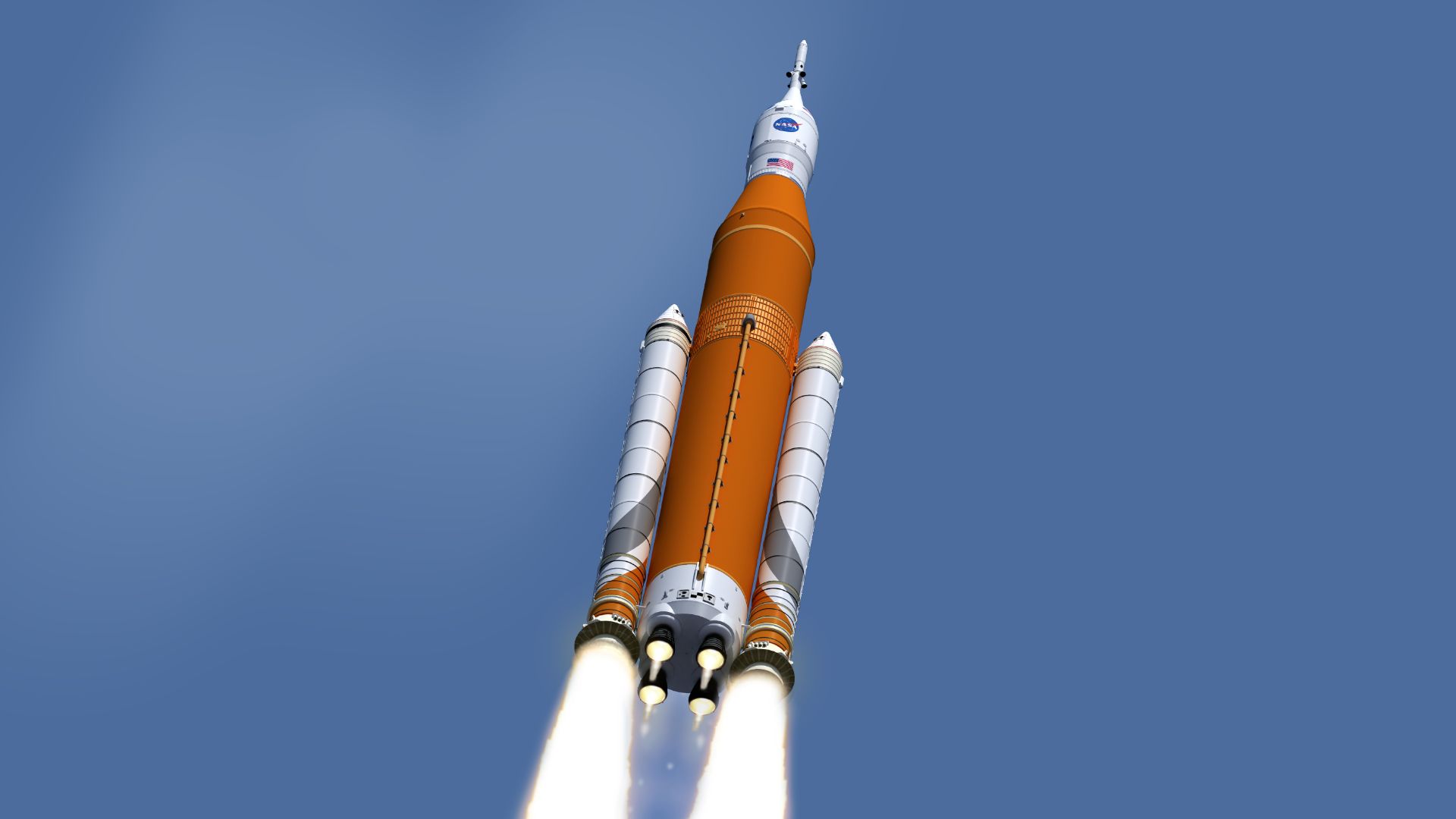

Spent Upper Stages

The math is brutal: getting to space requires multiple rocket stages, and what goes up doesn't always come down—at least not right away. Spent upper stages represent about 11% of all catalogued space objects, making them a significant contributor to the orbital junkyard.

Spent Upper Stages (Cont.)

These hollow metal cylinders, some as large as school buses, once burned their fuel loads to push satellites into their final orbits before being unceremoniously abandoned. The problem is that many still contain residual fuel that can expand and rupture tanks in the harsh temperature swings of space.

Rocket Boosters

Every SpaceX Falcon 9 landing you've watched represents a revolution in rocket reusability, but historically, first-stage boosters were simply discarded after their brief moment of glory. These massive structures of tens of thousands of pounds, when empty, typically fall back to Earth within minutes of launch.

Rocket Boosters (Cont.)

When boosters do reach orbital velocities, they become some of the largest and most dangerous objects out there. Certain boosters break apart, creating debris clouds that increase the danger for active missions. For example, a recent Chinese Long March rocket broke apart in orbit.

Payload Fairings

Those smooth, aerodynamic nose cones that safeguard satellites during launch have a nasty habit of becoming expensive space litter worth millions of dollars each. SpaceX's fairing halves cost about $6 million per launch, which explains why they've developed ships with giant nets.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Payload Fairings (Cont.)

The physics of fairing separation presents a unique challenge, though. These lightweight shells can remain in orbit for much longer than expected due to their high surface area relative to their mass. When payload fairings fail to separate properly, they can doom entire missions.

U.S. Air Force photo/Airman 1st Class Christian Thomas, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Air Force photo/Airman 1st Class Christian Thomas, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

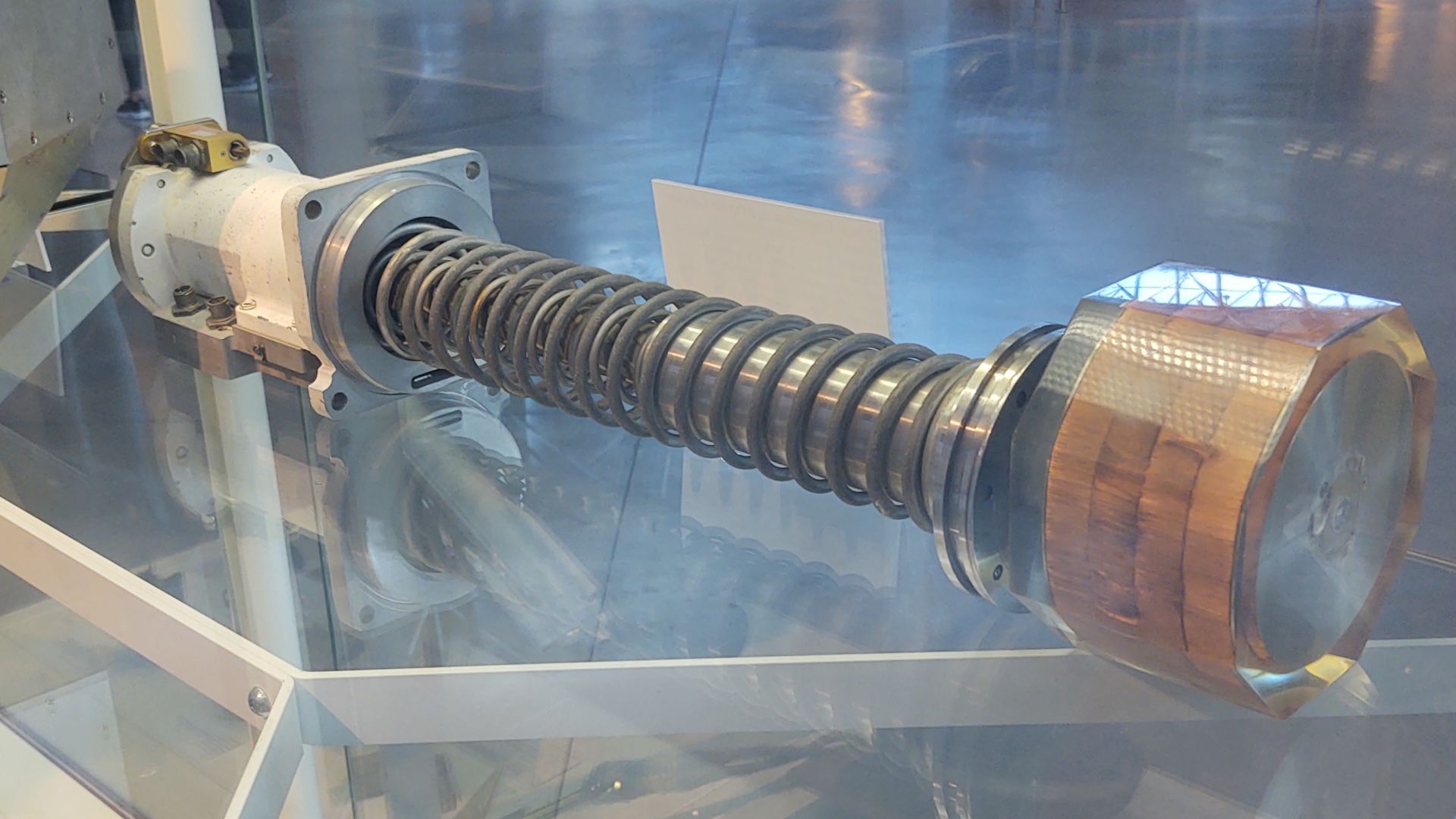

Launch Adapters

Launch adapters are essentially sophisticated clamps that secure satellites to rockets, designed with explosive bolts that fire with split-second precision to release payloads into orbit. The unsung heroes of space missions are the mechanical connectors that hold everything together during launch, until they don't.

Launch Adapters (Cont.)

Well, these adapters themselves become orphaned space objects once they've completed their singular purpose. Some weigh a lot of pounds and showcase complex geometries with multiple attachment points. Their size ranges vary, and like other debris, they range from large pieces visible to tracking systems to smaller fragments.

ClearSpace-1 Approaching the Space Debris by ClearSpace

ClearSpace-1 Approaching the Space Debris by ClearSpace

Lens Covers

Even the most sophisticated space telescopes need to protect their billion-dollar eyes during the violent ride to orbit. Still, those protective lens covers have to go somewhere once the instruments wake up. These are seemingly innocent caps, structured to shield delicate optics from contamination.

Lens Covers (Cont.)

What makes lens covers primarily insidious is their unpredictable trajectories, as they're often spring-loaded. According to sources, space agencies and international regulators have begun to emphasize minimizing the intentional release of such covers to reduce future debris hazards.

Ruffnax (Crew of STS-125), Wikimedia Commons

Ruffnax (Crew of STS-125), Wikimedia Commons

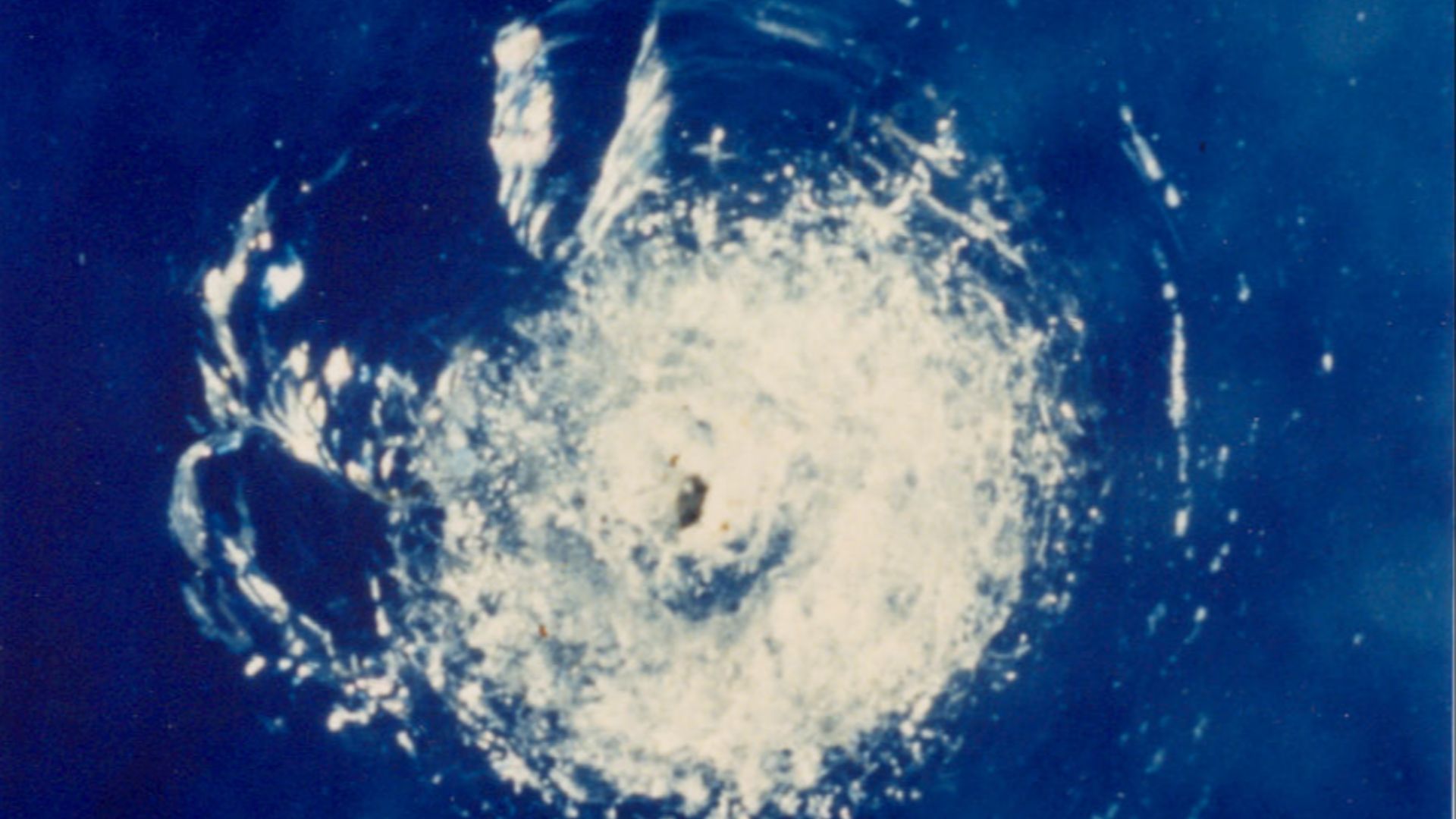

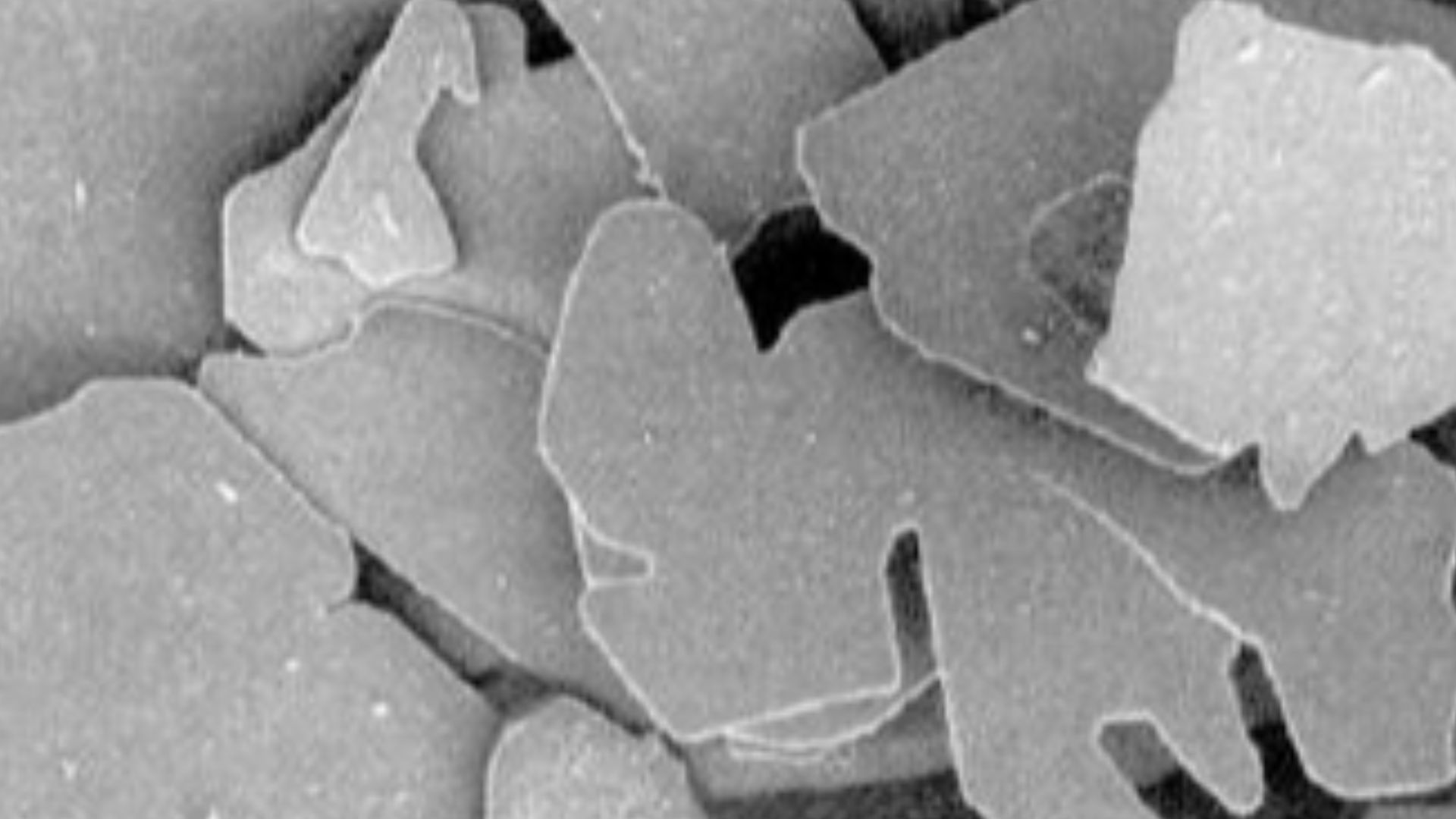

Paint Flecks

Don't let their microscopic size fool you. Paint flecks are the invisible assassins of space, capable of punching holes through spacecraft windows at hypervelocity speeds that make bullets look sluggish. These tiny chips peel off rockets and satellites due to thermal cycling and radiation exposure.

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

Paint Flecks (Cont.)

Furthermore, they travel at approximately 17,500 miles per hour in low Earth orbit. The paint fleck incident on the front window during STS-7 was the first confirmed orbital debris impact. The piece of paint was estimated to be about 0.76 mm in diameter.

Paint Flecks (Cont.)

This analysis was done using a scanning electron microscope, which identified the impactor as a paint chip traveling at an average velocity of about 9.3 km/s. This small paint chip caused a noticeable pit on the window but did not compromise the shuttle's integrity.

NASA HiRISE camera, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter., Wikimedia Commons

NASA HiRISE camera, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter., Wikimedia Commons

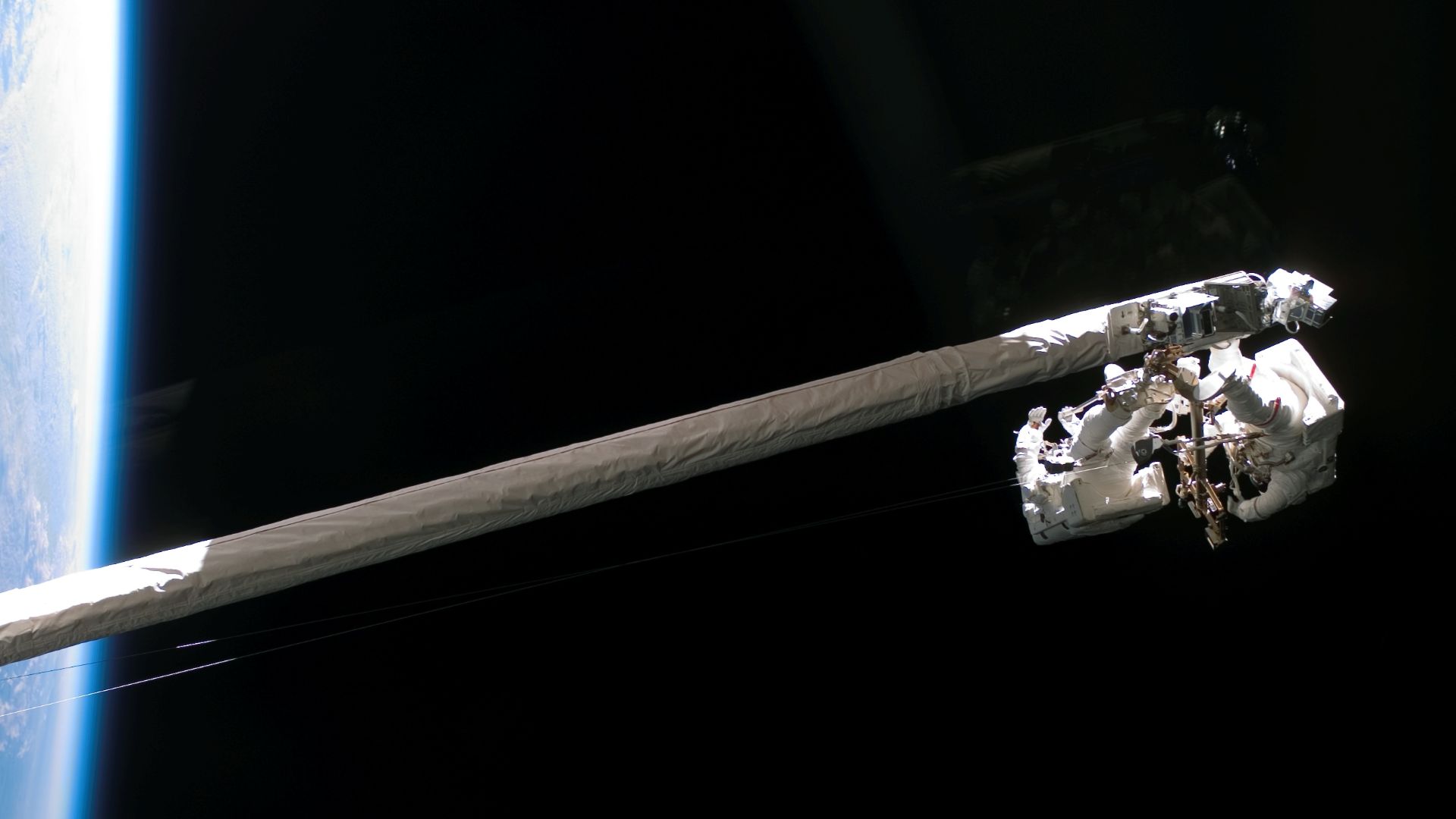

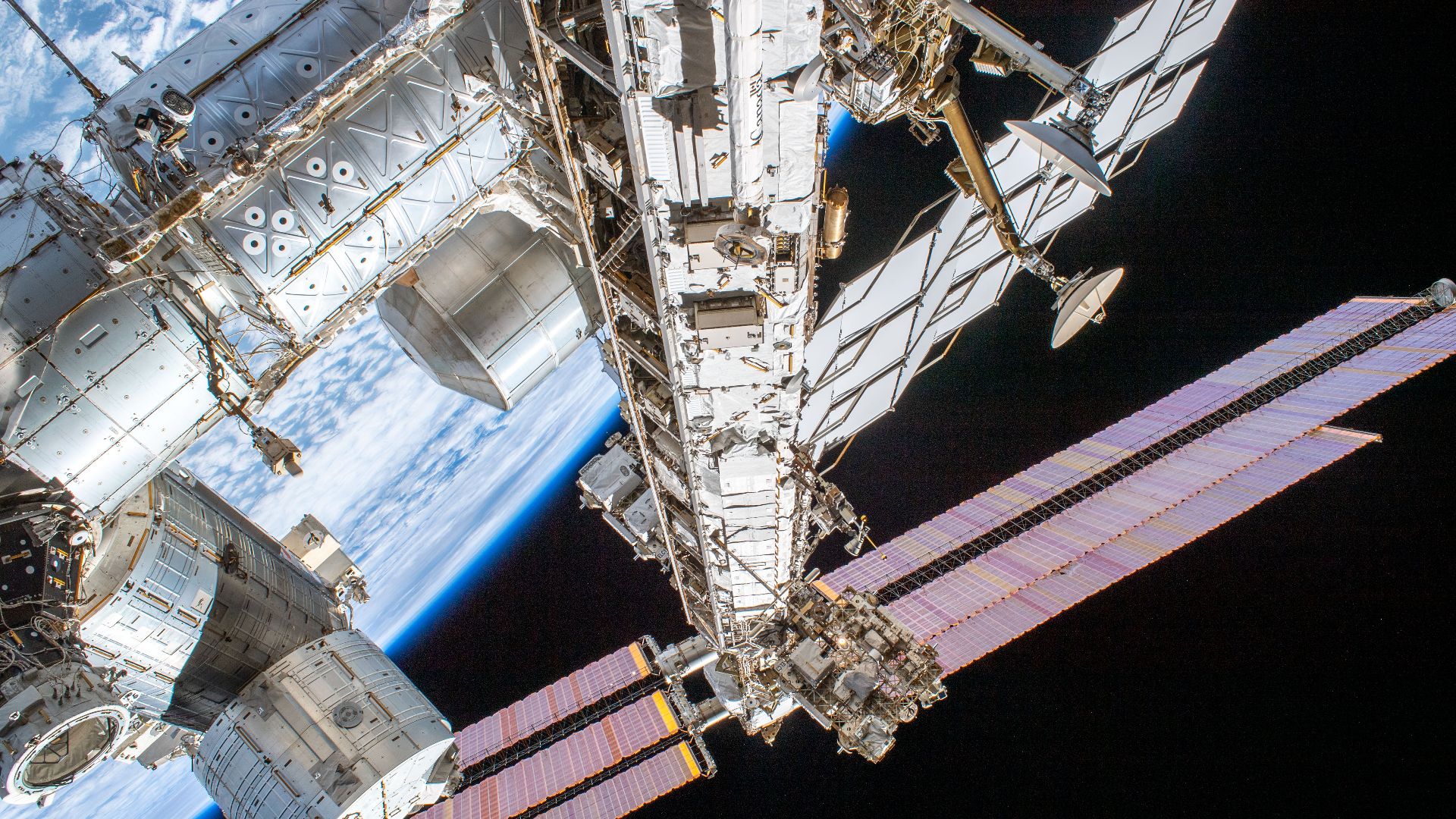

Astronaut Tools

Space is the ultimate workplace where dropping your hammer means watching $100,000 worth of specialized equipment become a potential projectile threatening the International Space Station. The bulky pressurized gloves astronauts wear limit their dexterity to about 20% of normal hand function.

Astronaut Tools (Cont.)

This makes tool fumbles practically inevitable during six-hour spacewalks. The cosmic tool graveyard includes everything from Ed White's famous lost glove during America's first spacewalk in 1965 to Heidemarie Stefanyshyn-Piper's entire tool kit that floated away in 2008—a briefcase-sized collection worth $100,000 containing grease guns.

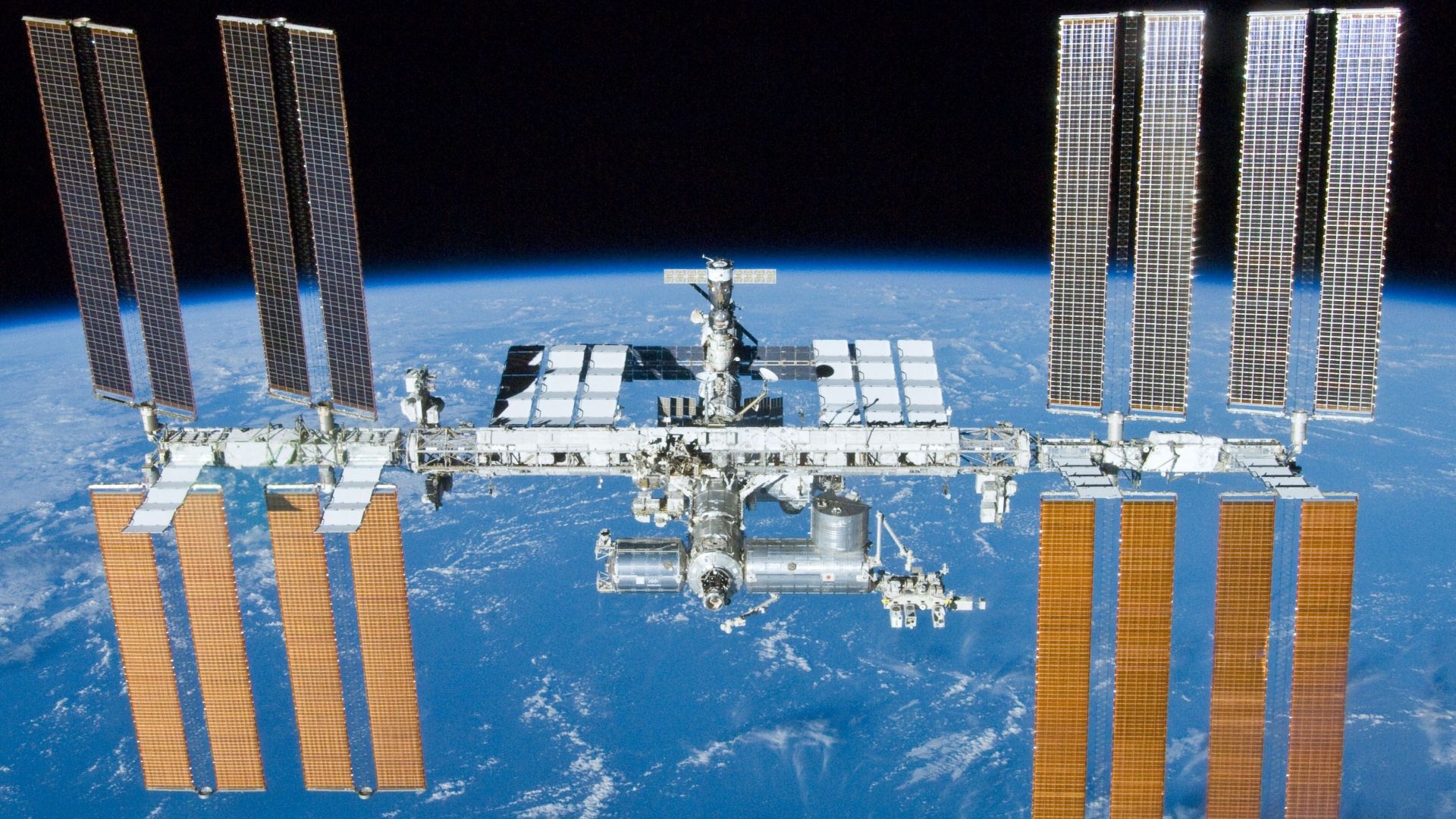

Tool Bags

The most recent addition to space's lost-and-found department was spotted tumbling past Earth in November 2023, bright enough to be visible through binoculars as it raced ahead of the International Space Station. This particular tool bag was lost during routine maintenance by astronauts Jasmin Moghbeli and Loral O'Hara.

Bill Ingalls, Wikimedia Commons

Bill Ingalls, Wikimedia Commons

Tool Bags (Cont.)

It became an impromptu celestial object that amateur astronomers could actually track and photograph. These items are large enough to cause catastrophic damage in a collision, yet light enough to have alleged orbital decay patterns. The 2023 tool bag was expected to remain in orbit for several months.

BobMacInnes, Wikimedia Commons

BobMacInnes, Wikimedia Commons

Lost Gloves

Ed White made history twice on June 3, 1965, first, as America's first spacewalker, and second, as the unwitting creator of one of space's most famous pieces of debris. His spare thermal glove, accidentally released during that pioneering EVA outside Gemini 4, became an instant legend.

Lost Gloves (Cont.)

It was captured on film as it moved away into the cosmic void. The irony is profound: the same pressurized gloves that keep astronauts alive also make them clumsy enough to lose things regularly. Modern EVA gloves are essentially miniature spacesuits themselves, complete with heating elements.

Bolts And Washers

The Space Shuttle Endeavour crew learned a frustrating lesson about orbital mechanics during a 2006 spacewalk when astronaut Joe Tanner unknowingly released a bolt, spring, and washer while working outside the International Space Station. These small components weigh mere ounces.

Bolts And Washers (Cont.)

They instantly become high-velocity projectiles capable of puncturing spacecraft hulls. Apparently, every space mission involves thousands of bolts, screws, and washers, and Murphy's Law guarantees that some will inevitably break free. During a 2011 spacewalk, astronauts encountered mysterious bolt failures where retaining washers were either missing or bent.

Photo Courtesy of NASA, Wikimedia Commons

Photo Courtesy of NASA, Wikimedia Commons

Wire Ties

Cable management up there involves the same humble plastic zip ties used in offices everywhere, except when astronaut Drew Feustel lost one during a 2018 spacewalk, it joined the exclusive club of objects orbiting Earth at 17,500 miles per hour. These seemingly insignificant fasteners serve critical roles.

Wire Ties (Cont.)

How? By securing the countless cables and wires that snake across the International Space Station's exterior. The loss of a single wire tie might seem trivial until you consider that these plastic strips are designed to last decades in the harsh environment of space.

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

Wire Ties (Cont.)

Mission planners must account for every wire tie because loose cables can interfere with docking operations, solar panel deployment, or robotic arm movements. When Feustel's wire tie disappeared into the void, it was more than just a minor operational inconvenience.

NASA/Crew of STS-132, Wikimedia Commons

NASA/Crew of STS-132, Wikimedia Commons

Spatulas

Piers Sellers probably never imagined that losing a kitchen utensil would make space history. Still, his 14-inch spatula became one of the most unusual additions to Earth's orbital debris collection during a 2006 Space Shuttle mission. The spatula was part of an experimental thermal tile repair system.

Lauren Harnett, Wikimedia Commons

Lauren Harnett, Wikimedia Commons

Spatulas (Cont.)

It was made to fix heat shield damage like that which doomed Columbia. The experiment involved testing various "goos" that could be injected into damaged thermal protection tiles and then smoothed with the spatula, representing NASA's desperate attempt to develop in-orbit repair capabilities.

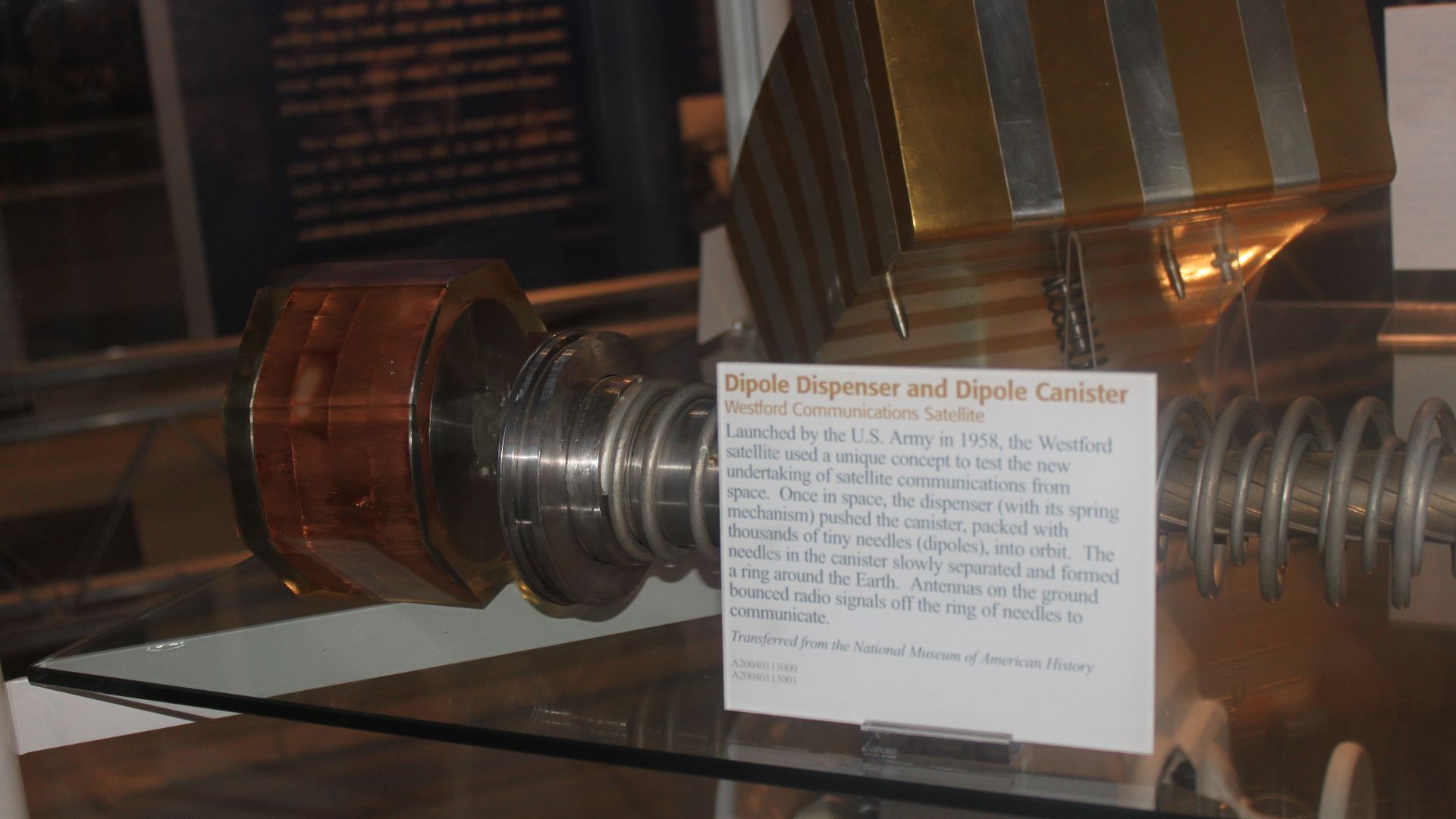

West Ford Needles

In 1963, the United States crafted Earth's first artificial ring system by releasing 480 million copper needles into orbit, each precisely 1.28 centimeters long and thinner than human hair. Project West Ford was the military's audacious attempt to form a permanent communication system.

GeneralNotability, Wikimedia Commons

GeneralNotability, Wikimedia Commons

West Ford Needles (Cont.)

Each needle was exactly half the wavelength of 8 GHz radio signals, structured to act as tiny dipole antennas that would mirror military communications. While most needles fell back to Earth within a few years due to solar radiation pressure, some clumped together and remain in orbit today.

Edmund.huber, Wikimedia Commons

Edmund.huber, Wikimedia Commons

Coolant Droplets

Soviet nuclear-powered reconnaissance satellites from the 1970s and 1980s created another highly unusual pollution problem. It happened when they ejected their reactor cores at the end of their missions, releasing thousands of droplets of sodium-potassium coolant into orbit.

NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (NASA-MSFC), Wikimedia Commons

NASA Marshall Space Flight Center (NASA-MSFC), Wikimedia Commons

Coolant Droplets (Cont.)

These metallic spheres represent the atomic age's contribution to the growing junkyard above our heads. The physics of liquid metal in spacecraft is a particularly persistent problem. These droplets solidify into spherical beads that resist atmospheric drag much better than irregularly shaped debris.

NSSDC, NASA[1], Wikimedia Commons

NSSDC, NASA[1], Wikimedia Commons

Coolant Droplets (Cont.)

Unlike paint flecks or metal fragments that eventually spiral back to Earth, coolant droplets can remain in orbit. As a result, this causes a diffuse cloud of radiation-hardened projectiles. NASA's Orbital Debris Program specifically tracks this population because the droplets are dense enough to penetrate spacecraft shielding.

Ronald C. Wittmann, Wikimedia Commons

Ronald C. Wittmann, Wikimedia Commons

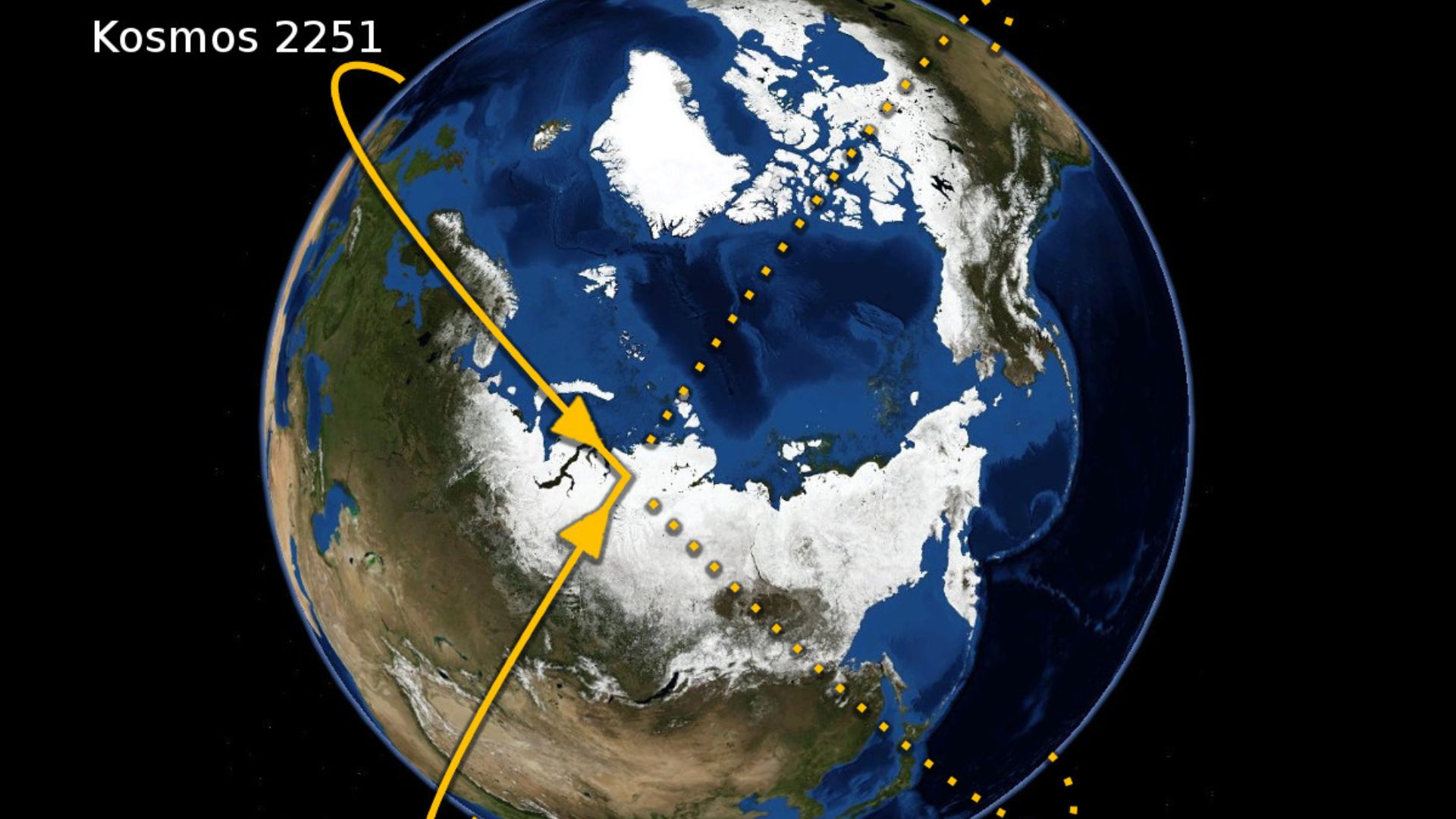

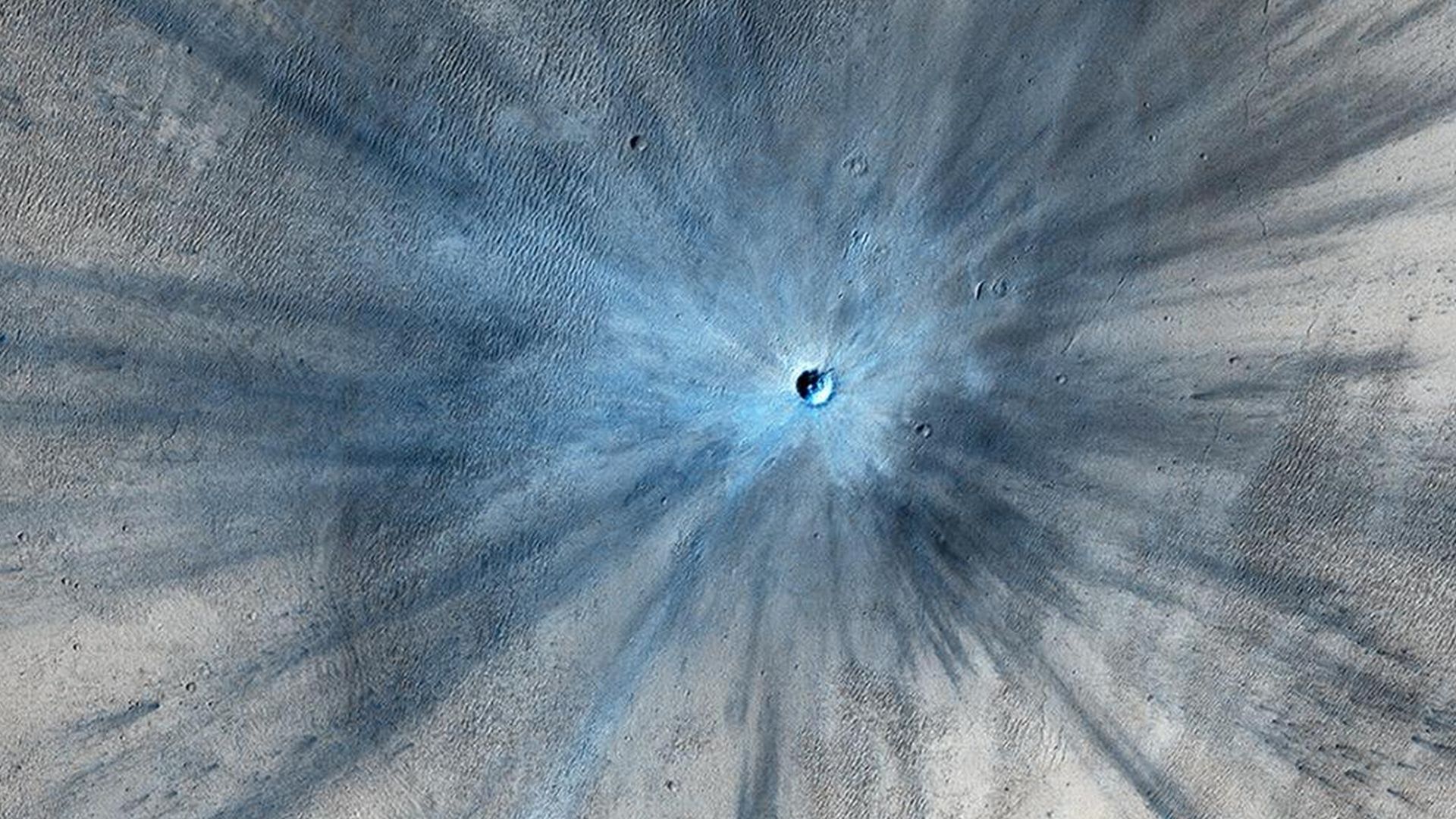

Collision Debris

February 10, 2009, marked the first time two intact satellites accidentally collided in space, when the operational Iridium-33 communications satellite and the defunct Russian Cosmos-2251 reconnaissance satellite smashed into each other at 11.7 kilometers per second.

Simulation des GPS / Varol Okan, Genti Ismaili, Wikimedia Commons

Simulation des GPS / Varol Okan, Genti Ismaili, Wikimedia Commons

Collision Debris (Cont.)

It occurred at a closing speed of over 26,000 miles per hour, fragmenting both spacecraft into numerous pieces. The collision occurred 490 miles above northern Siberia and created a debris field that spread across multiple orbital altitudes, with fragments ranging from large chunks to microscopic particles.

Animation shows spread of debris from satellite collision by New Scientist

Animation shows spread of debris from satellite collision by New Scientist

Collision Debris (Cont.)

The kinetic energy involved is equivalent to exploding several tons of TNT, pulverizing spacecraft into clouds of high-velocity shrapnel. The Iridium-Cosmos collision alone formed more than 2,000 trackable pieces larger than 10 centimeters, each one capable of destroying another satellite in a cascade effect.

Rocket Motor Particles

The exhaust from solid rocket motors doesn't just disappear into space—it leaves behind millions of tiny aluminum oxide particles, each one a reminder of humanity's chemical-powered journey to the stars. These byproducts of the solid propellant combustion power everything from Space Shuttle boosters to military missiles.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Rocket Motor Particles (Cont.)

The particles come to life when aluminum powder in solid rocket fuel burns with an oxidizer, producing aluminum oxide slag that gets expelled along with the hot gases. It is said that the cumulative effect is like flying through a sandstorm at hypersonic speeds.

Thermal Blanket Pieces

Here, temperature swings of hundreds of degrees can cause materials to expand and contract with relentless mechanical stress. The gold-colored multi-layer insulation blankets that give spacecraft their distinctive appearance have an unfortunate tendency to delaminate and shed pieces in the harsh environment of space.

Thermal Blanket Pieces

These thermal protection systems, critical for maintaining equipment temperatures, gradually deteriorate and leave fragments. NASA's post-flight analysis of the European Retrievable Carrier (Eureca) spacecraft revealed extensive areas of thermal blanket delamination after just 11 months in orbit, with clearly visible damage.

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

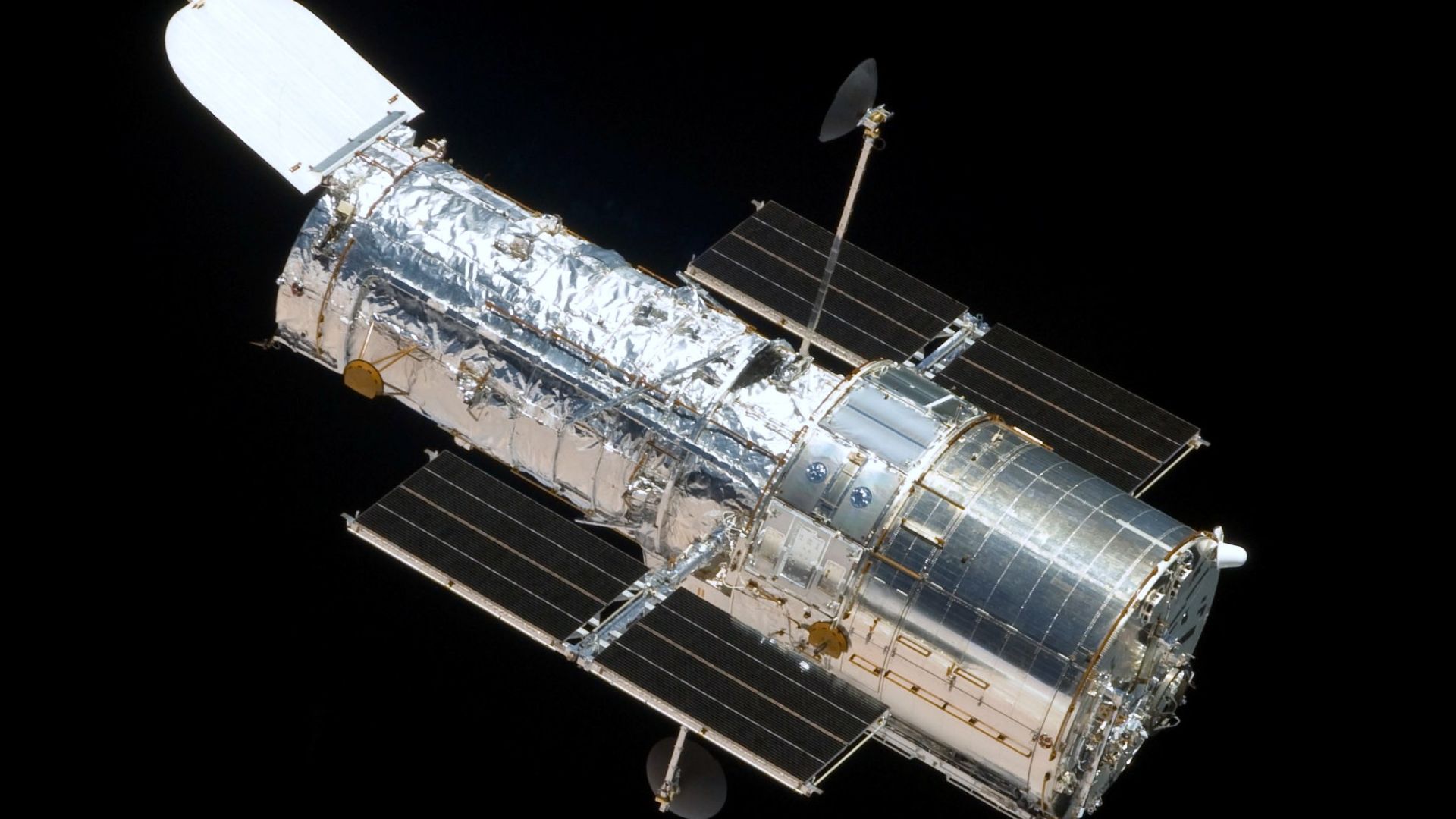

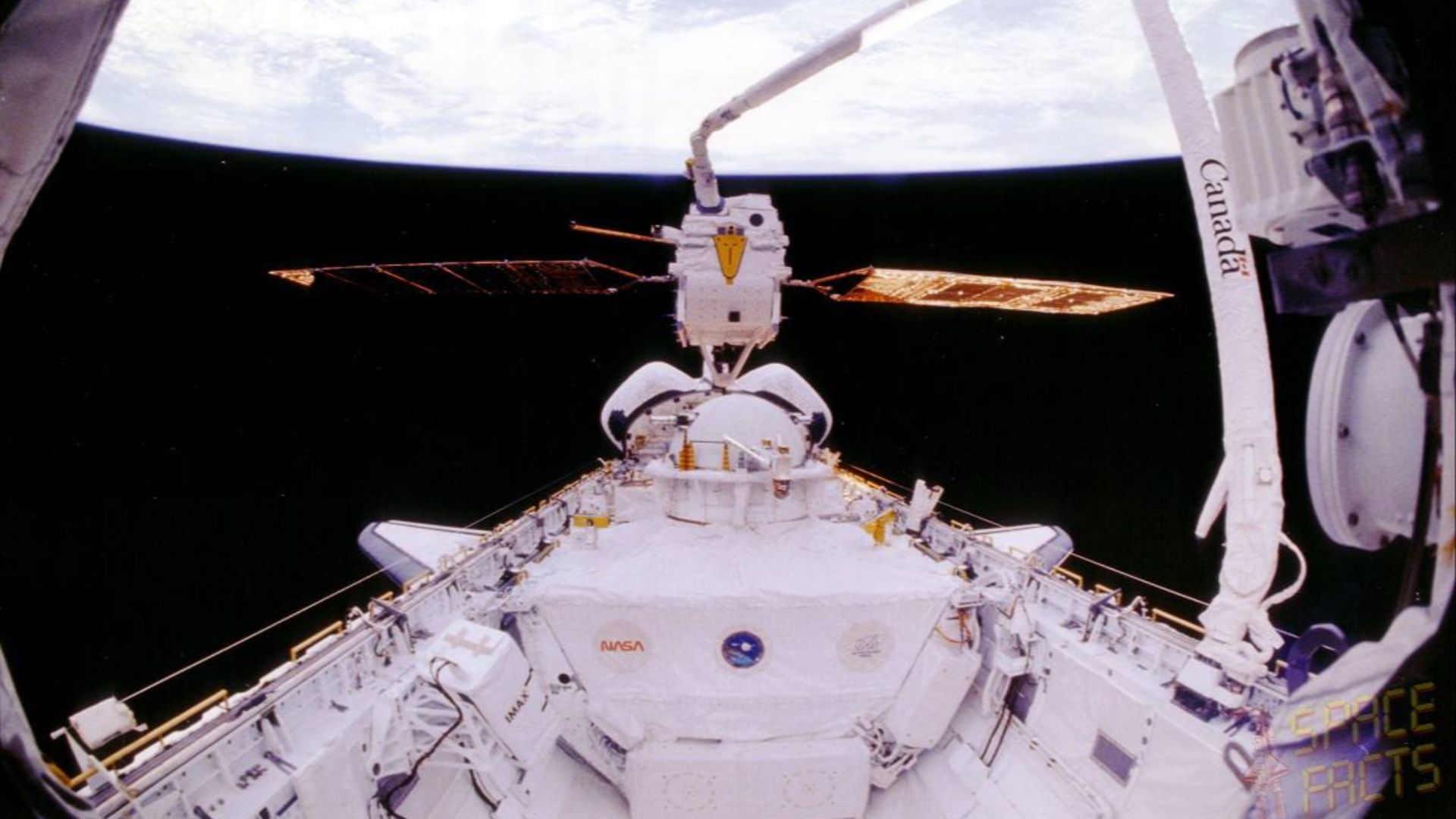

Solar Panel Fragments

The Hubble Space Telescope's solar arrays tell a violent story written in thousands of impact craters, with a couple of complete penetrations documented in just eight years of exposure to the cosmic shooting gallery. These silicon cells and backing material serve as inadvertent collectors of space debris impacts.

Solar Panel Fragments (Cont.)

They gradually accumulate damage that ranges from microscopic pits to holes large enough to see with the unaided eye. The combination of silicon cells, metal backing, and electrical wiring forms fragments with sharp edges and unpredictable shapes that tumble chaotically through space.

Steve Jurvetson from Menlo Park, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Steve Jurvetson from Menlo Park, USA, Wikimedia Commons

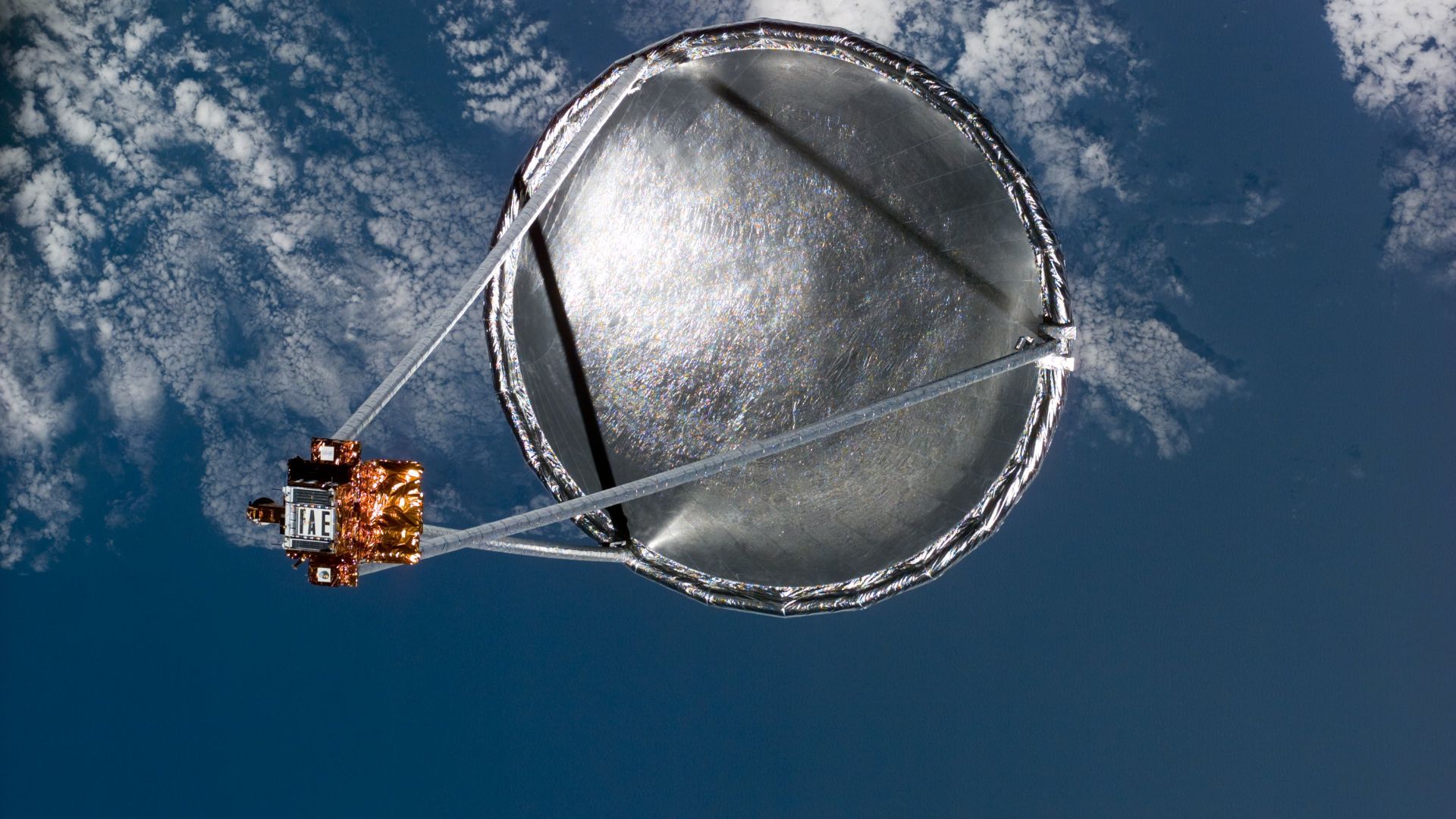

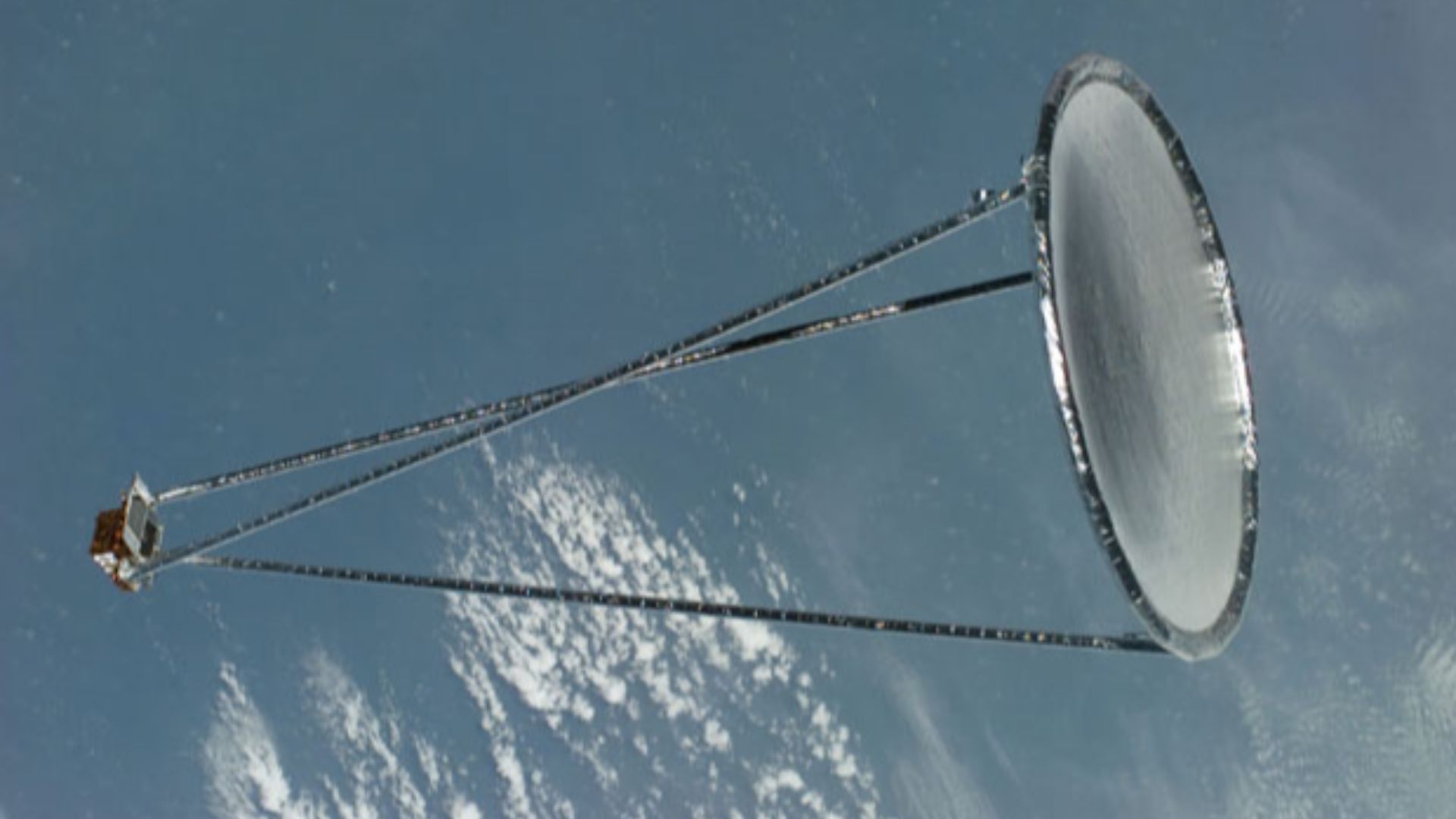

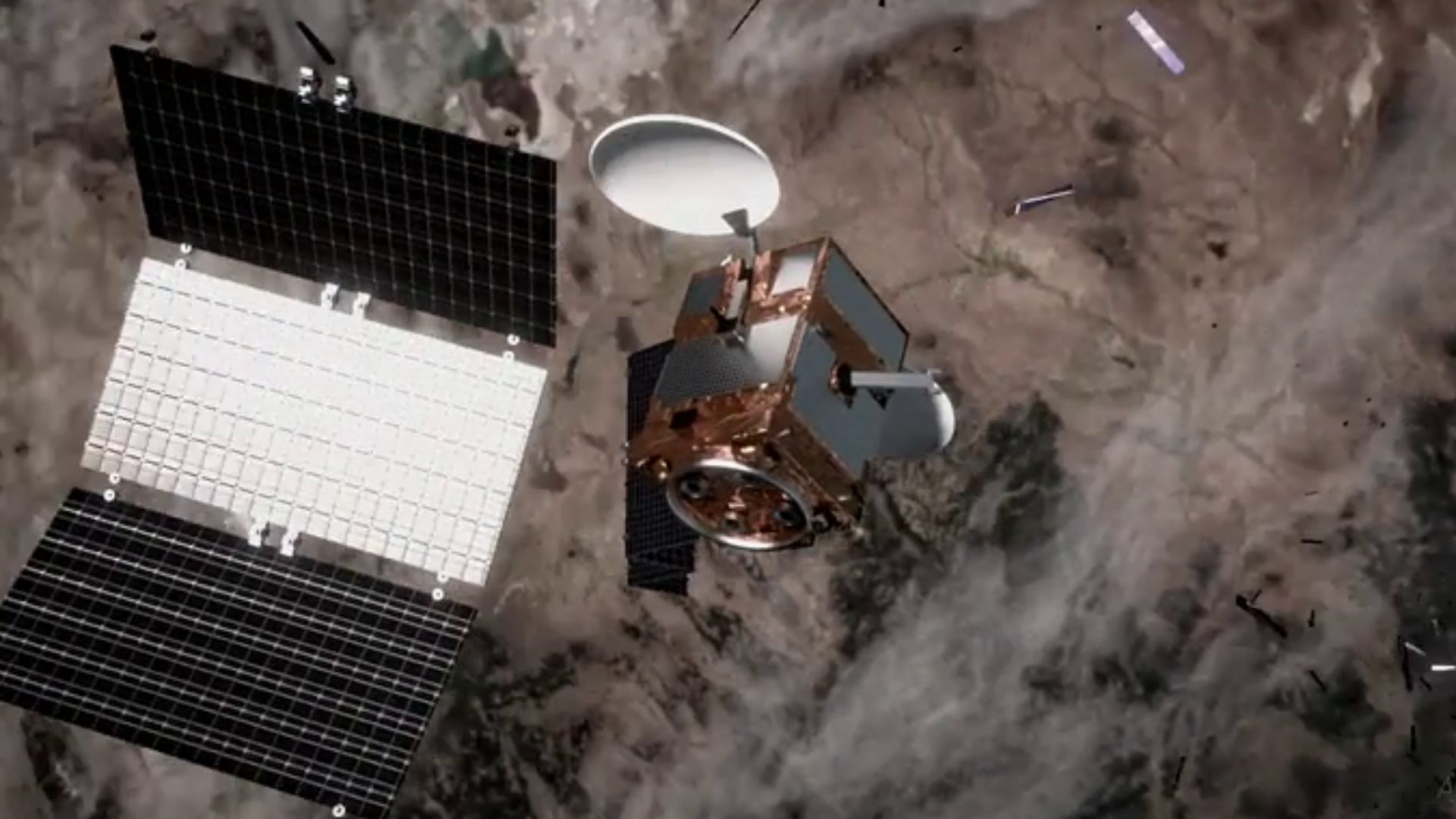

Antenna Components

Some communication antennas deploy, extend, and sometimes detach completely to function correctly. These components range from simple wire antennas that snap off during deployment to complex dish assemblies that separate after use, each one representing a calculated trade-off between mission success and orbital cleanliness.

Antenna Components (Cont.)

The deployment mechanisms themselves often involve springs, explosive bolts, and mechanical actuators that can malfunction and let out unexpected matter into space. NASA's tracking systems have catalogued numerous antenna-related objects, from the obvious large dishes to the subtle release of antenna covers.