Glamour To Gray

She was built to pamper the rich across the Atlantic. Then Hitler invaded Poland, and everything changed overnight. The Queen Mary got painted gray, stuffed full of soldiers, and sent racing through submarine-infested waters.

Thcipriani, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Thcipriani, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Luxury Afloat

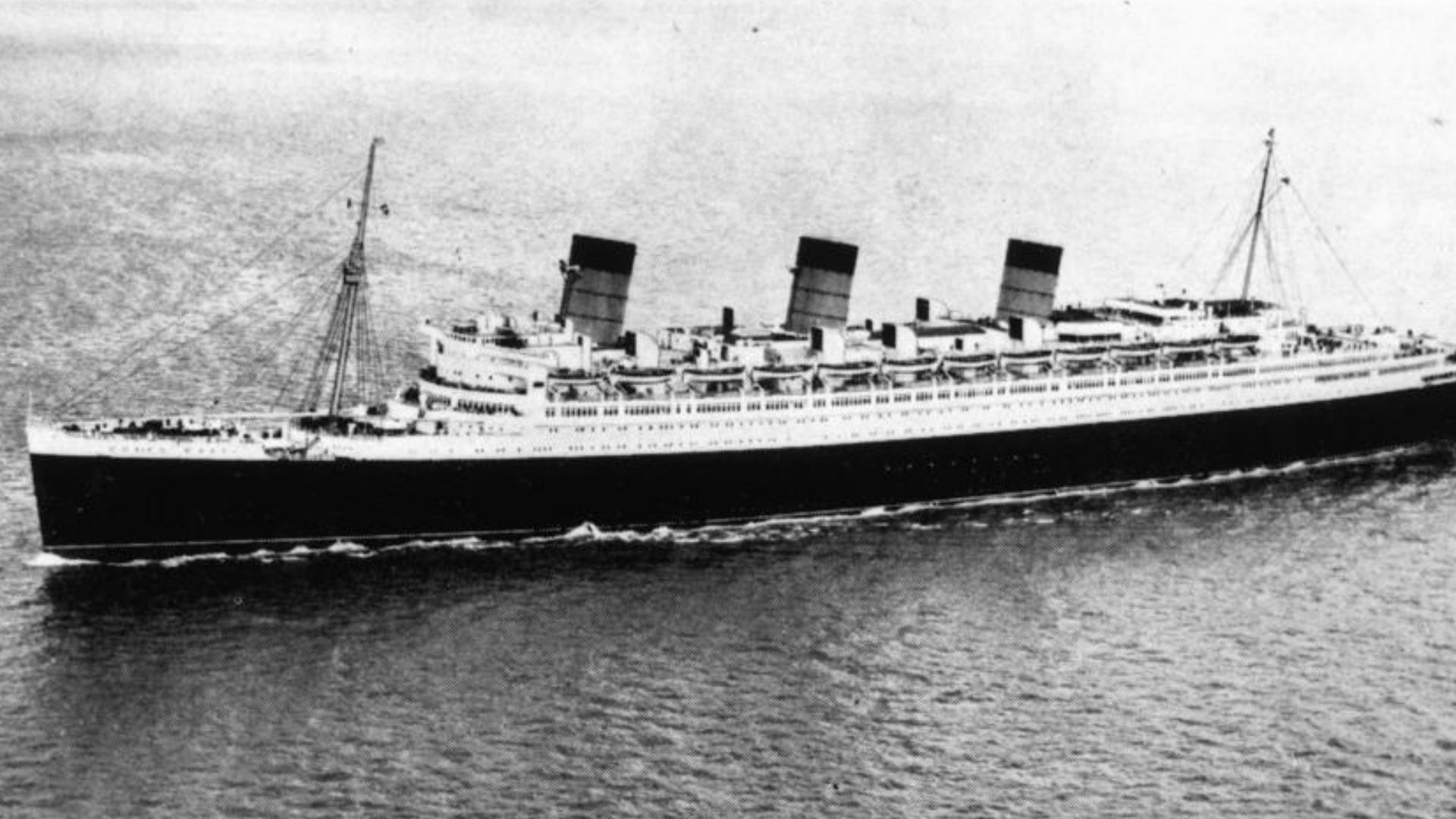

When the RMS Queen Mary slid down the slipways at John Brown's shipyard in Clydebank, Scotland, on September 26, 1934, she wasn't just another ocean liner—she was Britain's answer to fierce transatlantic competition from French and German superships.

Tom from USA, Wikimedia Commons

Tom from USA, Wikimedia Commons

Depression Delays

Construction began in December 1930 as "Hull Number 534," but the Great Depression's crushing economic grip forced Cunard to halt all work by December 1931. For over two years, the unfinished hull sat rusting on the Clyde. The British government finally intervened in 1934 with an important loan.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Blue Riband

Speed became Queen Mary's calling card almost immediately. On her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York in May 1936, she averaged 28.73 knots and captured the coveted Blue Riband for fastest Atlantic crossing within months. The Blue Riband represented supremacy on the world's most profitable shipping route.

Mfield, Matthew Field, http://www.photography.mattfield.com, Wikimedia Commons

Mfield, Matthew Field, http://www.photography.mattfield.com, Wikimedia Commons

War Arrives

August 30, 1939, marked the Queen Mary's final peacetime departure from Southampton. Among her record 2,332 passengers were comedian Bob Hope and his wife, Dolores, fleeing Europe as war clouds gathered ominously. The ship was already 100 miles south of her normal route.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Requisition Orders

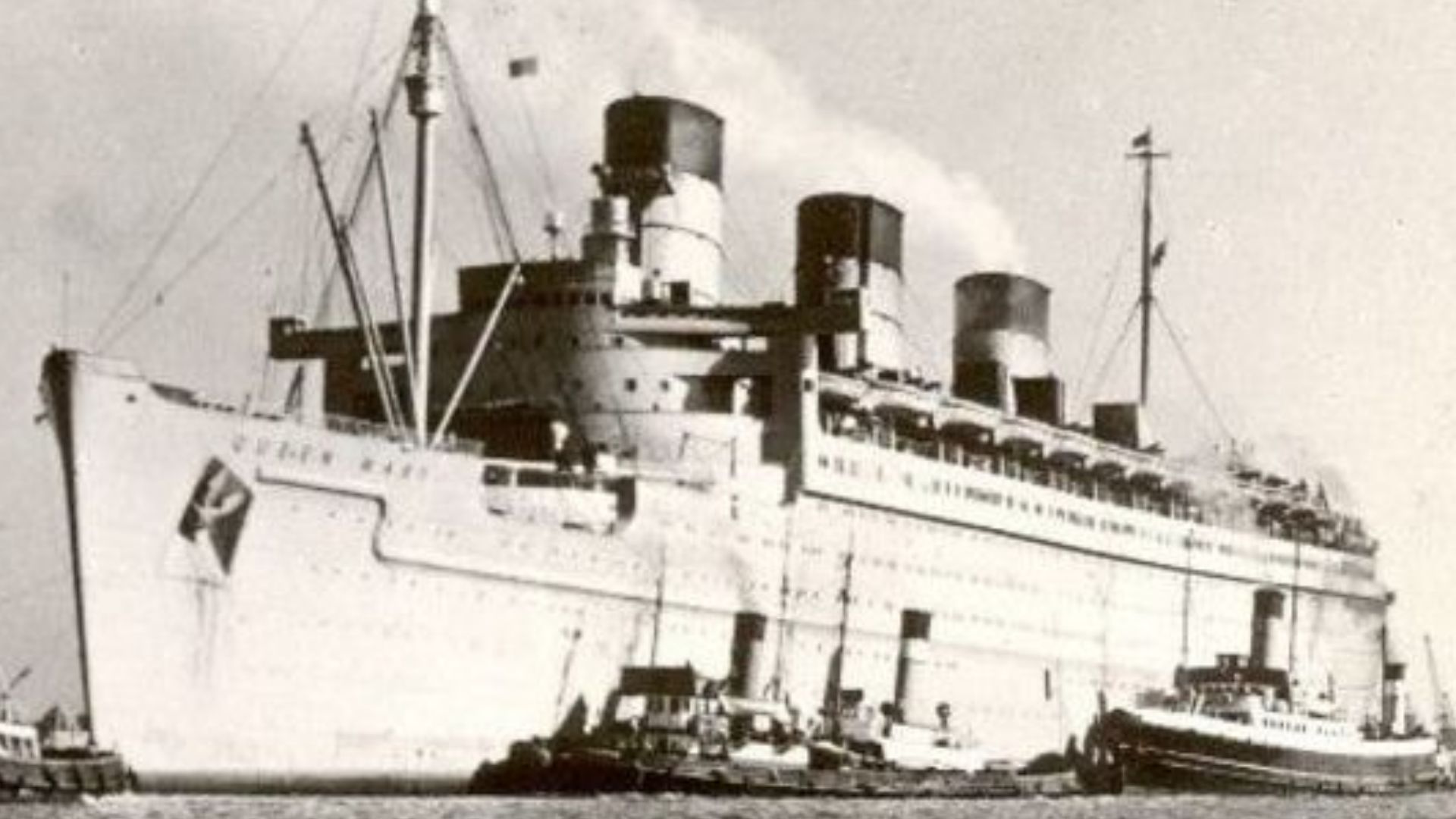

The Queen Mary languished at Cunard's New York pier through autumn and winter 1939–1940 while British officials debated her fate at the highest government levels. Should she continue civilian service? Become a hospital ship? In March 1940, the decision came: Britain desperately needed troop capacity.

Sydney Transformation

Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Company in Sydney accomplished an engineering marvel in just fourteen days during April-May 1940. What had been the world's most luxurious ocean liner was systematically gutted and rebuilt for war. Six miles of plush carpeting were rolled up and stored.

Frank Norton, Wikimedia Commons

Frank Norton, Wikimedia Commons

Gray Ghost

That battleship-gray paint job earned the Queen Mary her legendary wartime nickname, but "Gray Ghost" meant more than just color. It represented her phantom-like ability to vanish across oceans before German U-boats could target her. Admiral Karl Dönitz's submarine commanders knew she was out there somewhere.

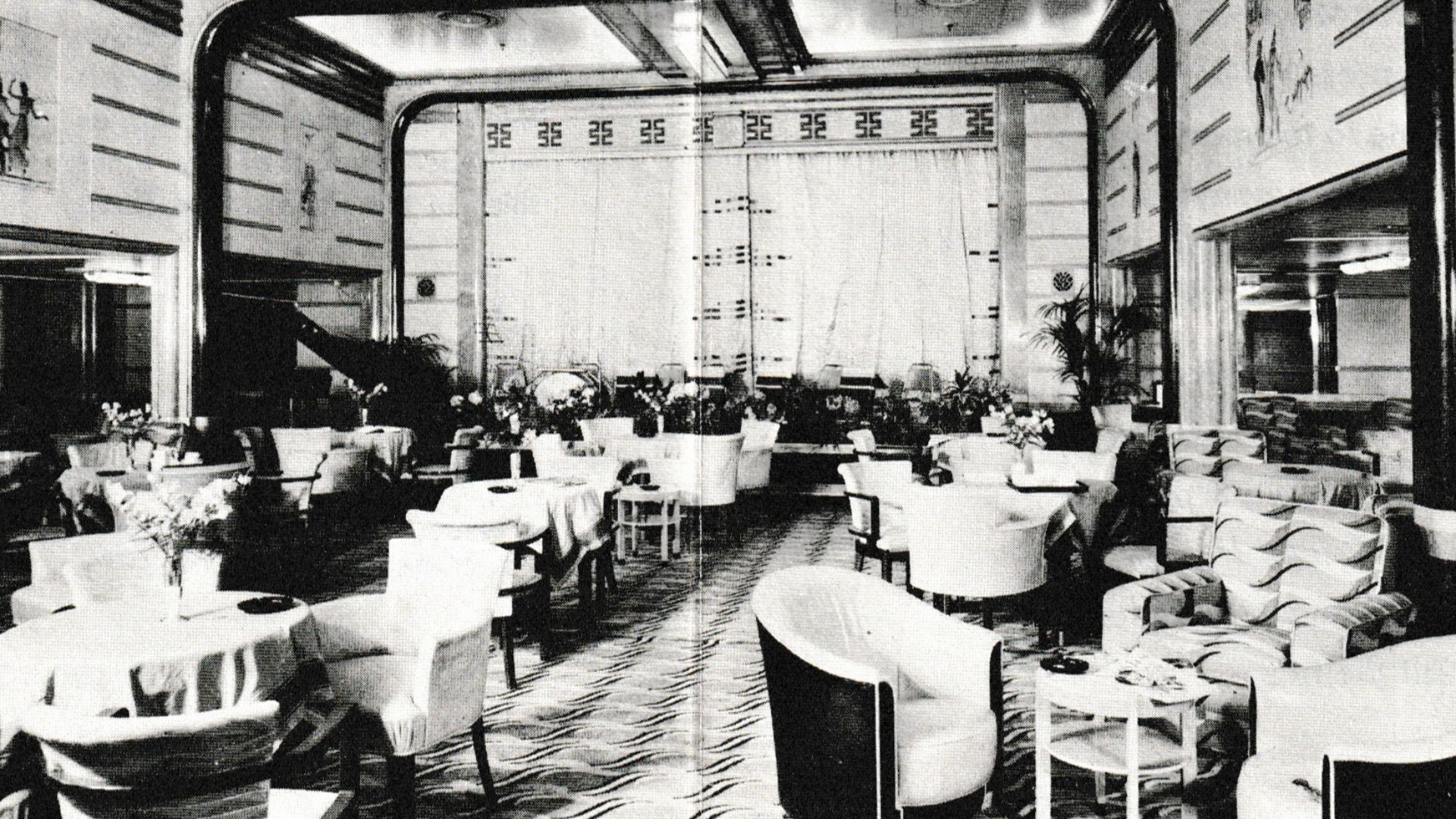

Stripped Interiors

Inside the changed Queen Mary, luxury had completely vanished. Where tuxedoed passengers once dined beneath crystal chandeliers, soldiers now queued with metal trays for British cooking they universally despised—kidneys, mutton stew, and boiled cabbage. The opulent first-class staterooms now held crude wooden bunks stacked five to seven high.

Cunard White Star Line, Wikimedia Commons

Cunard White Star Line, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Bunks Installed

The mathematics of wartime transport was brutal and ingenious. Engineers calculated every square foot of usable space and crammed in bunks wherever physics allowed. Hammocks swung in corridors. Canvas cots filled the drained swimming pool. Mostly five-tier bunks replaced single beds in cabins originally designed for two passengers.

David Krieger, Wikimedia Commons

David Krieger, Wikimedia Commons

Capacity Maximized

By 1942, the Queen Mary routinely transported over 15,000 troops per crossing, nearly seven times her peacetime passenger capacity. But the ultimate record came in July 1943 when she departed New York carrying 16,683 people: 15,740 troops and 943 crew members.

derivative work: Altair78 (talk) Queen Mary forecastle.jpg: :Altair78, Wikimedia Commons

derivative work: Altair78 (talk) Queen Mary forecastle.jpg: :Altair78, Wikimedia Commons

Hitler's Bounty

Adolf Hitler understood Queen Mary's strategic value instantly. Every two weeks, she delivered 15,000 fresh American troops to Britain. His response was extraordinary: one million Reichsmarks and Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross, Germany's highest military honor, to any U-boat captain who could sink her.

U-Boat Gauntlet

January to August 1942 was "the happy time" for German submariners they were annihilating Allied shipping. During these eight months, U-boats sank 609 Allied vessels totaling 3.1 million tons. The Queen Mary's February 1942 voyage from Boston occurred during this deadliest period.

Willy Stower, Wikimedia Commons

Willy Stower, Wikimedia Commons

Speed Defense

Speed was the boat’s only real protection against submarine attack. Her maximum speed exceeded 32 knots while German torpedoes traveled approximately 25 knots, and U-boats managed merely 8 knots submerged or 13–14 knots surfaced. On May 25, 1944, U-853 spotted the Queen Mary and submerged to attack position.

File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske), Wikimedia Commons

File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske), Wikimedia Commons

Zigzag Patterns

The Queen Mary followed "Zigzag Pattern No 8," precise naval maneuvers designed to confuse submarine targeting. Rather than steaming straight, she executed timed course changes at specific intervals, constantly altering heading by calculated degrees. This made predicting her future position nearly impossible for U-boat commanders.

Andrew Eick, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Eick, Wikimedia Commons

Overcrowded Decks

Conditions aboard were nightmarish. With 15,000 troops crammed into spaces designed for 2,000 passengers, every corridor, lounge, and deck space overflowed with humanity. Men slept in shifts using "hot bunking"—when one group vacated their bunks for duty, another group immediately claimed them.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Curacao Collision

October 2, 1942, brought disaster off the Irish coast. HMS Curacoa, a WWI-era anti-aircraft cruiser converted to escort duty, rendezvoused with the Queen Mary carrying 15,000 American troops of the 29th Infantry Division. Both captains had made fatal assumptions.

Royal Navy official photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Royal Navy official photographer, Wikimedia Commons

337 Dead

The Curacoa's stern section vanished almost immediately, watertight doors trapping crew members below decks. Her forward section floated briefly before following, leaving hundreds of sailors struggling in freezing North Atlantic waters. Seaman Ernest Watson described watching his crewmates being tossed "like falling autumn leaves" into the ocean.

Pelman, L (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Pelman, L (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer, Wikimedia Commons

No Rescue

Well, the boat steamed onward without stopping, leaving British sailors drowning in her wake. This was a military necessity under strict Admiralty orders. Stopping would turn her into a stationary U-boat target, potentially killing all 15,000 troops aboard. Crew and passengers watched in horror.

Compagnie des Arts Photomecaniques, 44, rue Letallier, Paris-15, Wikimedia Commons

Compagnie des Arts Photomecaniques, 44, rue Letallier, Paris-15, Wikimedia Commons

Secret Tragedy

The collision remained classified for three years. Witnesses aboard both ships were immediately sworn to secrecy under military regulations, revealing that the incident could demoralize troops. The British public heard nothing while families of the 337 dead received only vague notifications about their loved ones.

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Record Voyage

Despite the Curacao tragedy, the Queen Mary achieved her most remarkable feat in late July 1943. She departed New York carrying 16,683 people, the most humans ever transported aboard a single vessel. This record stands unbroken over 80 years later.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Rogue Wave

On December 11, while carrying 11,339 troops and crew approximately 700 miles from Scotland, a massive storm engulfed the ship. Suddenly, without warning, a rogue wave estimated at 92 feet high slammed broadside into the starboard side with catastrophic force.

Churchill Aboard

Winston Churchill crossed the Atlantic aboard the Queen Mary three times during the battle, traveling under the pseudonym "Colonel Warden" to maintain secrecy. The British Prime Minister later stated the Queen's "challenged the fury of Hitlerism in the battle of the Atlantic".

Harold William John Tomlin, Wikimedia Commons

Harold William John Tomlin, Wikimedia Commons

Court Battle

The Curacoa collision triggered a bitter three-year legal battle that didn't conclude until 1949. Initially, Mr Justice Pilcher exonerated the ship’s crew entirely, placing all fault on Curacoa's officers in January 1947. The Admiralty immediately appealed, seeking compensation for the 337 lost sailors and the destroyed cruiser.

Pelman, L (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Pelman, L (Lt), Royal Navy official photographer, Wikimedia Commons

War's End

After Germany's surrender in May, she began Operation Magic Carpet. In early 1946, the ship carried thousands of war brides and their children to new lives in America and Canada in a single crossing. That same year, she also made her fastest-ever Atlantic crossing.