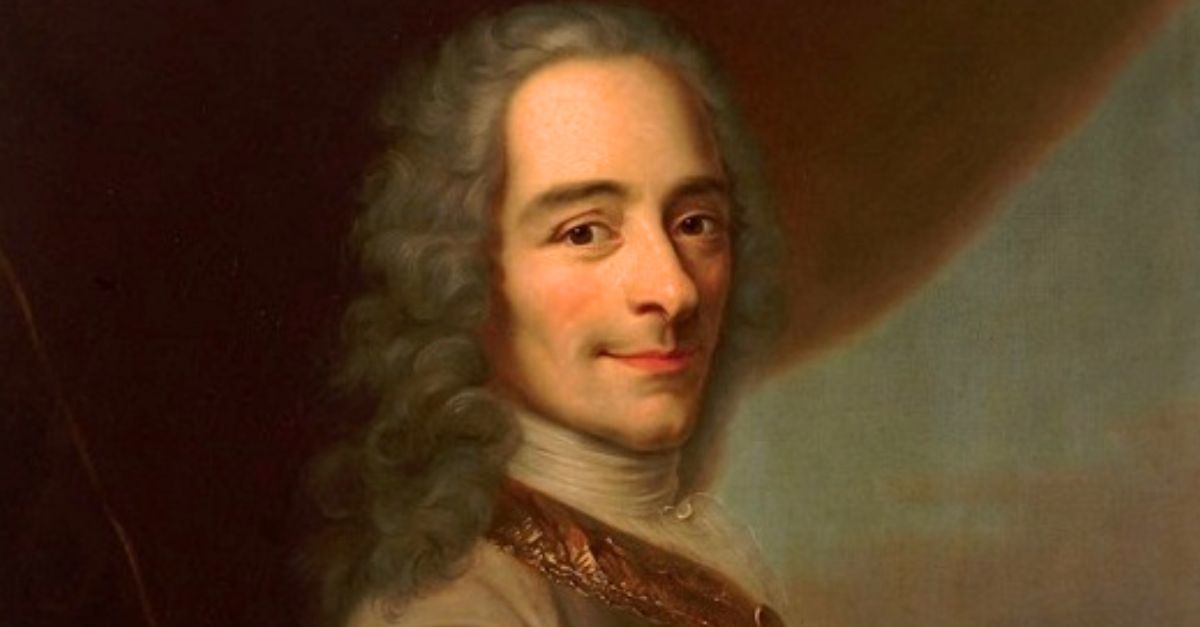

After Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Wikimedia Commons

After Maurice Quentin de La Tour, Wikimedia Commons

The line “I Disapprove of What You Say…” gets tossed around so casually that many people assume it came straight from Voltaire’s quill. Dig into the record, though, and the story flips. The quote wasn’t his at all.

Voltaire—born Francois-Marie Arouet—built his legacy on sharp wit and bold defenses of civil liberties, so the assumption isn’t surprising. Still, the actual line came from a biographer trying to capture his spirit, and here is how that unfolded.

How The Wrong Line Became The Right Soundbite

The famous sentence—“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it”—first appeared in 1906, more than a century after Voltaire’s death. Evelyn Beatrice Hall, a British writer also known by the pen name SG Tallentyre, crafted it in her biography The Friends of Voltaire as a summary of his attitude. She used it to capture Voltaire’s broader defense of free expression, especially in disputes involving writers like Claude-Adrien Helvetius.

This one line carried a rhythm that felt authentically Enlightenment-era, so readers embraced it without checking the source. As a result, the phrasing spread through political debates and early free-speech advocacy until it became shorthand for Voltaire himself.

That brings us to a twist worth noting: Hall never claimed Voltaire said it. She wrote it as narrative commentary. Over time, the nuance blurred, and the quote fused to his reputation like wet ink drying into parchment.

Alfred Agache (1843–1915), Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Agache (1843–1915), Wikimedia Commons

What Voltaire Actually Wrote About Speaking Freely

Voltaire’s real defense of expression shows up in correspondence and pointed essays where the tone is sharper, more sarcastic, and grounded in real conflict. His genuine stance emerges through lines such as “Think for yourselves and allow others the privilege to do so too,” and his relentless attacks on censorship by church and monarchy.

These writings came from a man who knew the sting of government pressure firsthand—books burned and threats of prison humming in the background like a persistent draft through a cracked window. He argued fiercely for open criticism, even when his targets outranked him. That energy matches the spirit of the misattributed line, but the words remain Hall’s.

Connecting the historical record to modern misunderstandings gives the quote new weight. People treat it like a declaration, but Voltaire’s commitment to free expression showed up in what he did—supporting censored writers and pressuring authorities to justify their decisions.

How A Misattribution Became A Cultural Shortcut

Hall’s sentence hit a sweet spot. It was concise and easy to remember. And it entered political culture at a moment when free-speech debates surged across Europe and America.

Newspapers, editorial writers, and even early civil-liberties groups repeated it until memory overpowered accuracy. The line became a stand-in for Enlightenment ideals, a compact slogan that fit neatly into speeches printed on crisp broadsheets.

The quote’s popularity isn’t surprising. Voltaire already represented rebellion against censorship, so people attached the statement to him without hesitation. It felt right, sounding like something he’d toss into a heated salon argument while waving a quill with theatrical flair. And once a crowd repeats a line often enough, attribution becomes background noise.

The next connection follows naturally: this doesn’t diminish Voltaire’s actual principles. If anything, the quote’s longevity proves how effectively Hall captured his temperament.

Nicolas de Largillière (1656–1746), Wikimedia Commons

Nicolas de Largillière (1656–1746), Wikimedia Commons

Why It Still Matters To Get The Source Right

Accuracy shapes interpretation. Misquoting him creates a polished version of his beliefs—one that simplifies the messy, combative reality of his political battles. Voltaire didn’t defend speech because he was polite. He defended it because he believed power rotted without scrutiny. His real writing crackles with that conviction.

Knowing the true origin of the quote also highlights how easily modern culture trims history into slogans. It shows how commentary and summaries can quietly become “quotes” when audiences stop checking where the words came from.

Understanding the difference pushes you to read deeper, question sources, and recognize how ideas shift as each generation retells them. And that’s a reminder Voltaire himself would’ve enjoyed.

The Line Endures, But The Credit Belongs Elsewhere

Evelyn Beatrice Hall shaped a sentence that echoed Voltaire’s spirit better than any single quote he left behind, but the words remain hers. The misattribution doesn’t erase his passionate defense of expression—it just shows how powerful storytelling can reshape memory.

Dmedvedev83, Wikimedia Commons

Dmedvedev83, Wikimedia Commons