Frozen Past

The mountain had been holding on for millennia. Then came the melt. What appeared next weren’t merely artifacts but fragments of lives lived with skill and a deep connection to the place.

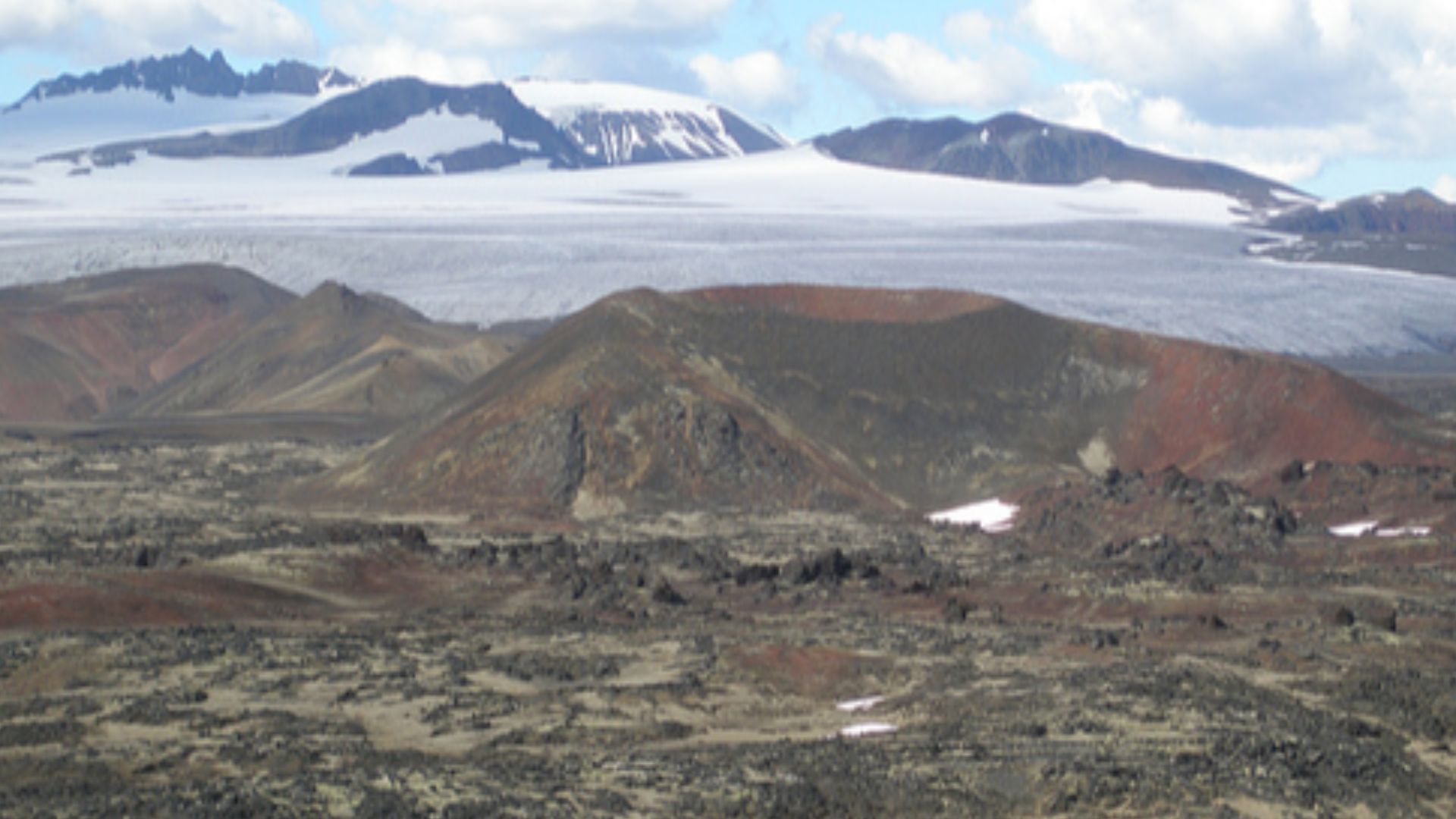

Volcanic Formation

Deep in British Columbia's wilderness, a volcanic giant began its dramatic rise over one million years ago. Mount Edziza erupted skyward to 2,786 meters, creating a frozen fortress crowned with glaciers and an ice-filled crater. This mountain unknowingly crafted the perfect time capsule.

Ethan Reitz, Wikimedia Commons

Ethan Reitz, Wikimedia Commons

Indigenous Settlement

Long before European explorers dreamed of these remote mountains, the Tahltan Nation called this rugged landscape home. They gazed upon the towering peak and named it "Tenh Dzetle" or Ice Mountain. For over 10,000 years, such resourceful people thrived in one of Earth's most challenging environments.

Andrew Jackson Stone (1859–1918), Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Jackson Stone (1859–1918), Wikimedia Commons

Clan Structure

The Tahltan Nation organized its society around two primary matrilineal clans: Tses' Kiya (Crow) and Chiyone (Wolf), with membership determining marriage partnerships and social responsibilities. These clans were subdivided into four distinct family groups: Kartchottee (Raven), Nanyiee (Wolf), Talarkoteen (Wolf), and Tuckclarwaydee (Wolf).

Diamond Jenness, Wikimedia Commons

Diamond Jenness, Wikimedia Commons

Language Heritage

Tahltan belongs to the Northern Athabaskan language family, with approximately 30–35 fluent speakers remaining as of recent linguistic surveys. The language shares similarities with neighboring Kaska and Tagish dialects, though some linguists classify these as separate languages rather than regional variants.

Miles Brothers, Wikimedia Commons

Miles Brothers, Wikimedia Commons

Territorial Extent

This territory encompasses over 95,933 square kilometers of northwestern British Columbia, including major river drainages flowing toward both the Pacific and Arctic oceans. The area includes the Liard, Stikine, Iskut, and Nass river systems, providing access to various ecological zones.

david adamec, Wikimedia Commons

david adamec, Wikimedia Commons

Resource Conflicts

Modern Tahltan communities have faced issues from industrial development proposals, notably the Klappan Coalbed Methane Project that threatened sacred headwaters areas. The Klabona Keepers, a group of Tahltan elders, established roadblocks between 2005 and 2012 to prevent Shell Oil Company's exploration activities in culturally sensitive places.

Klabona Keepers trailer by VIFF

Klabona Keepers trailer by VIFF

Cultural Continuity

Well, contemporary Tahltan leadership continues advocating for the protection of ancestral sites like Mount Edziza. Chad Norman Day, president of the Tahltan Central Government, emphasized in 2021 that Mount Edziza "has always been sacred to the Tahltan Nation" and provided essential resources for centuries.

Chad Norman Day - Part of Our Culture (U) by Who Cares? BC

Chad Norman Day - Part of Our Culture (U) by Who Cares? BC

Sacred Territory

To these folks, Mount Edziza wasn't just a mountain. It was a living connection to their ancestors and the spirit world. The Raven was often featured as a protector in oral traditions. Moreover, this sacred peak anchored their cultural universe.

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Geological Complexity

The mountain’s volcanic complex consists of at least six geological formations created during separate eruption cycles. The Pyramid Formation, Ice Peak Formation, Pillow Ridge Formation, Edziza Formation, Kakiddi Formation, and Big Raven Formation each produced different rock types and volcanic elements.

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

Glacial History

During the Pleistocene epoch, it was covered by massive regional ice sheets that advanced and retreated multiple times until approximately 11,000 years ago. These glacial cycles shaped the mountain's current topography, forming cirques, valleys, and ridges that influenced human settlement patterns and travel routes.

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Drainage System

Mount Edziza is drained by streams within the Stikine River watershed, including westward-flowing Elwyn Creek and Sezill Creek, which join Mess Creek, and eastward-flowing streams such as Tenchen Creek, Nido Creek, and Tennaya Creek that feed into Kakiddi Creek. All drainage ultimately flows into the Stikine River.

GerthMichael, Wikimedia Commons

GerthMichael, Wikimedia Commons

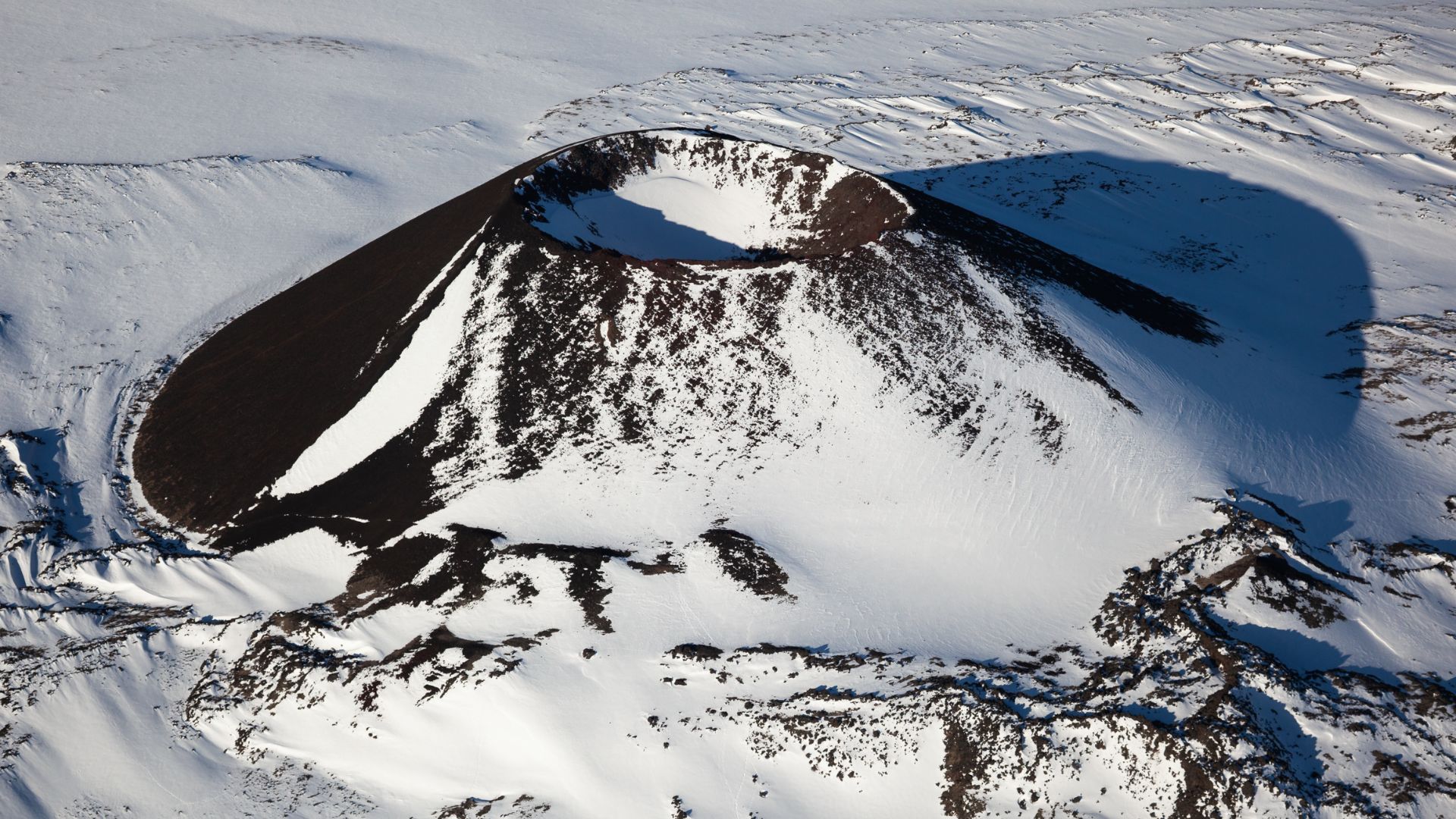

Modern Ice Cap

It currently supports a 70-square-kilometer ice cap measuring 15 kilometers long and 9 kilometers wide, making it the only noteworthy glacier system on the Stikine Plateau. Four named outlet glaciers, Idiji, Tenchen, Tencho, and Tennaya, descend between 1,700 and 2,000 meters above sea level.

Access Restrictions

This hill can only be accessed by aircraft or horse trails during the summer and early autumn months. No established road access exists, though the Stewart-Cassiar Highway and Telegraph Creek Road extend within 40 kilometers. Landing on certain lakes requires authorization letters.

Volcanic Hazards

Natural Resources Canada classifies Mount Edziza as a high-threat volcano due to its eruption rate throughout the Holocene period, surpassing all other Canadian volcanic centers. Potential future outbursts could produce lava flows capable of damming local rivers. The volcano possesses silica-rich trachyte and rhyolite compositions.

Obsidian Quarrying

High above the treeline, Tahltan craftsmen discovered nature's finest innovation. At bone-chilling elevations, around 2,000 meters, volcanic glass was weathered from ancient lava flows. These obsidian quarries became prehistoric workshops where skilled hands converted volcanic glass into razor-sharp tools.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

Trade Networks

Then emerged something extraordinary. The Mount Edziza obsidian began an epic journey across North America. These black tools traveled over 2.2 million square kilometers, reaching tribes from Alaska's frozen shores to Alberta's prairies. Archaeological evidence reveals this was a 10,000-year-old trade network.

Edziza 2020: Backpacking the Spectrum Range of Mount Edziza Provincial Park. by Steve Ruuth

Edziza 2020: Backpacking the Spectrum Range of Mount Edziza Provincial Park. by Steve Ruuth

Seasonal Hunting

When spring awakened the mountain valleys, Tahltan families went on orchestrated hunting expeditions that followed ancient rhythms older than written history. They tracked caribou migrations through treacherous mountain passes, established seasonal camps at strategic hunting grounds, and developed portable gear adapted for extreme weather.

daryl_mitchell from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

daryl_mitchell from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

Avalanche Tragedy

In 1974 or earlier, two Tahltan men named Johnny Edzerza and Hank Williams died in an avalanche while crossing the hill. Williams Cone on Mount Edziza's northeastern side was named for Hank Williams, while Eve Cone honors Johnny Edzerza's wife, Eve Brown Edzerza.

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

Traditional Tools

Tahltan toolmakers enhanced obsidian crafting to an art form that would impress today's precision engineers. They created specialized implements for every mountain survival need. These included delicate scrapers for preparing hides, wickedly sharp projectile points for hunting, and multi-purpose knives that served as both weapons and everyday tools.

Making Stone Tools - Obsidian by Donny Dust’s Paleo Tracks

Making Stone Tools - Obsidian by Donny Dust’s Paleo Tracks

Cultural Practices

Around flickering fires in mountain camps, the elders passed down survival wisdom through stories, songs, and hands-on training that prepared young people for life in this unforgiving environment. They taught weather prediction by reading cloud patterns, navigation using stars and landmarks, and spiritual protocols.

Climate Warming

After thousands of years of stable ice accumulation, something began changing in Mount Edziza's high-altitude environment. Global climate trends shifted, bringing warmer temperatures that started nibbling away at older ice patches. What had been frozen solid for millennia began its slow surrender to rising thermometers.

Ethan Reitz, Wikimedia Commons

Ethan Reitz, Wikimedia Commons

Ice Melting

By the late 2010s, this mountain’s ice patches were retreating at a swift pace, exposing dark rocky surfaces that hadn't seen sunlight for thousands of years. Two consecutive winters brought very low snowpack, accelerating the melting process and giving rise to excavation opportunities.

Jagged Ridge Imaging, Wikimedia Commons

Jagged Ridge Imaging, Wikimedia Commons

Research Planning

Previous studies had focused primarily on obsidian quarries and stone tool manufacturing sites, but the ice patches remained largely unexplored. Researchers developed systematic survey methods to examine nine specific ice patch locations across the Big Raven Plateau, coordinating with Tahltan Nation representatives to ensure culturally appropriate research.

Jagged Ridge Imaging, Wikimedia Commons

Jagged Ridge Imaging, Wikimedia Commons

Summer Expedition

The research team accessed Mount Edziza Provincial Park during the brief summer window when weather conditions allowed safe travel to high-elevation locations. Helicopter transport delivered archaeologists to hidden ice patches scattered across the volcanic plateau, each place requiring careful documentation and GPS mapping.

Research Team Details

This archaeological survey was conducted by Duncan McLaren, Brendan Gray, Rosemary Loring, Tssema Igharas, Rolf Mathewes, Lesli Louie, Megan Doxsey-Whitfield, Genevieve Hill, and Kendrick Marr. This collaboration brought together expertise in archaeology, geology, Indigenous knowledge systems, and conservation science.

Ice Patch Survey

Methodical examination of exposed ground around retreating ice margins revealed promising signs of human activity. Archaeologists walked systematic transects, photographing and recording the precise location of every artifact before collection. The survey covered areas where ice had recently melted, exposing frozen organic materials.

First Discoveries

Initial artifact recovery yielded over 50 individual items preserved in remarkable condition by the ice's natural refrigeration effect. The first specimens included fragments of worked wood, pieces of birch bark with visible stitching, and carved antler tools that retained fine surface details. Scientists immediately recognized the brilliant preservation quality.

Sheila Sund , Wikimedia Commons

Sheila Sund , Wikimedia Commons

Preservation Methods

These findings required immediate stabilization to prevent deterioration after being stored in frozen conditions for decades. Field conservation involved gentle cleaning with soft brushes, careful moisture control, and protective wrapping using archival materials. Temperature changes posed the greatest risk to organic artifacts suddenly exposed to modern environmental conditions.

Initial Analysis

Laboratory examination displayed the diverse range of materials and manufacturing techniques represented in the artifact collection. A preliminary assessment identified worked birch bark, carved wood, stitched hide, shaped antlers, and bone tools. Additionally, microscopic analysis indicated fine details, including stitching patterns, tool marks, and surface treatments.

Franco Atirador, Wikimedia Commons

Franco Atirador, Wikimedia Commons

Birch Containers

Two remarkable birch bark containers demonstrated advanced Indigenous basket-making technology from thousands of years ago. The first specimen featured folded bark with two parallel rows of careful stitching along one edge, with original stitching material still threading through precisely punched holes.

Birch Containers (Cont.)

The second container incorporated wooden reinforcement sticks stitched into the sides, suggesting it was designed as a heavy-duty transport basket. This structural reinforcement implies it was intended to carry substantial loads, which were possibly obsidian, food, or other supplies, across rugged mountain terrain.

Stitched Footwear

A 6,200-year-old moccasin-like boot spotted in British Columbia’s Mount Edziza Provincial Park stands as the oldest known footwear from this region. This remnant was constructed from two different thicknesses of animal hide, skillfully stitched together using sinew thread.

Stitched Footwear (Cont.)

Following an in-depth examination, multiple stitching locations, visible knots, and complex seaming patterns were identified, all of which underscore advanced leatherworking skills. The boot’s layout mirrors practical adaptations for traversing rocky, uneven mountain terrain, offering durability and insulation in a cold region.

Antler Tools

A 5,300-year-old caribou antler had been structured into a multi-functional ice pick with three working surfaces. One tine was sharpened to a fine point for penetrating ice, another was blunted for use as a hammer, and the third appeared broken but likely functioned as a handle grip.

Walking Staffs

Several wooden walking staffs recovered from the ice patches showed woodworking techniques adapted for mountain travel. These implements were carved from local hardwood species. The staff had polished surfaces where hands repeatedly gripped the wood and pointed tips worn smooth from contact with stone surfaces.

Wooden Implements

Carved wooden handles were also found, which featured attachment points for stone or bone tool heads. Beveled sticks displayed precise angles, suggesting they were used as wedges or prying tools. The wood preservation allowed researchers to identify specific tree species selected by earlier craftspeople.

FactinateDating Process

FactinateDating Process

Radiocarbon dating analysis required careful selection of organic material samples from thirteen different artifacts to establish accurate age ranges. Hence, laboratory technicians extracted small samples of wood, bark, and hide for carbon-14 testing, following strict protocols to prevent contamination. Apparently, these artifacts spanned multiple periods.

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

Age Verification

Dating results confirmed that the collection represented an extraordinary 7,000-year timeline of continuous human presence in the Mount Edziza region. The oldest specimens are dated to approximately 6,900 years before the present, while the youngest remnants are roughly 1,500 years old.

7000-Year Span

Well, previous archaeological evidence had suggested only seasonal or occasional visits to high-elevation sites, but the continuous 7,000-year sequence indicated persistent and advanced adaptation to alpine environments. This discovery represented one of the longest documented records of high-altitude human activity in the Canadian subarctic region.

Bureau of Land Management Alaska, Wikimedia Commons

Bureau of Land Management Alaska, Wikimedia Commons

Cultural Layers

Then, a stratigraphic analysis of artifact distribution patterns was conducted, resulting in different cultural layers corresponding to various periods and technological traditions. Earlier artifacts showed simpler construction techniques, while later pieces showcased increasingly intricate manufacturing methods and tool designs.

Ethan Reitz, Wikimedia Commons

Ethan Reitz, Wikimedia Commons

Obsidian Context

Every organic find was found alongside extensive obsidian tool fragments, confirming the integration of volcanic glass technology with perishable material culture. Millions of obsidian flakes surrounded the preserved organic specimens, further indicating the intensive tool manufacturing activities that occurred at these locations.

B. Domangue, Wikimedia Commons

B. Domangue, Wikimedia Commons

Tahltan Connection

Contemporary Tahltan Nation members stated that the discovered artifacts aligned perfectly with traditional knowledge passed down through oral histories about ancestral mountain activities. Elders recognized manufacturing techniques, tool designs, and material choices that matched traditional practices described in cultural teachings. This correlation validated the research.

Tahltan Nation and Healthy Active Natives (Unity Staff Tour) by Tahltan Government Archives

Tahltan Nation and Healthy Active Natives (Unity Staff Tour) by Tahltan Government Archives

Museum Transfer

All recovered artifacts were transported to climate-controlled facilities at the Royal British Columbia Museum for long-term conservation and research storage. Professional conservators implemented specialized preservation protocols designed specifically for organic materials. Secure archival systems ensured permanent accessibility for future scientific investigations and cultural heritage programs.

Heritage Recognition

The findings made a big contribution to the formal recognition of Mount Edziza's cultural importance, leading to enhanced protection measures for the entire volcanic complex region. Government agencies acknowledged the site's exceptional archaeological value and established stricter access controls to prevent unauthorized artifact collection or site disturbance.

Luigi Zanasi, Wikimedia Commons

Luigi Zanasi, Wikimedia Commons

Preservation Urgency

Rapid ice loss at Mount Edziza and similar locations has demanded an archaeological emergency requiring immediate survey efforts to locate and preserve threatened cultural materials. Research teams are racing against time to document melting ice patches before centuries of warming destroy irreplaceable evidence of Indigenous cultural heritage.

Nashwatariq, Wikimedia Commons

Nashwatariq, Wikimedia Commons