Tracking The Planet’s Subtle Moves

Hearing the planet shifted feels like news we shouldn’t brush off. It doesn’t change your morning routine, yet the effect shows up in the activities that rely on Earth staying perfectly aligned.

What Scientists Actually Measured

The widely shared "31.5-inch tilt" headline doesn't mean Earth's lean changed. Scientists measured the rotational pole moving across Earth's surface by about 31.5 inches between 1993 and 2010. This reflects how mass shifted on the planet, not a change in Earth's actual tilt angle.

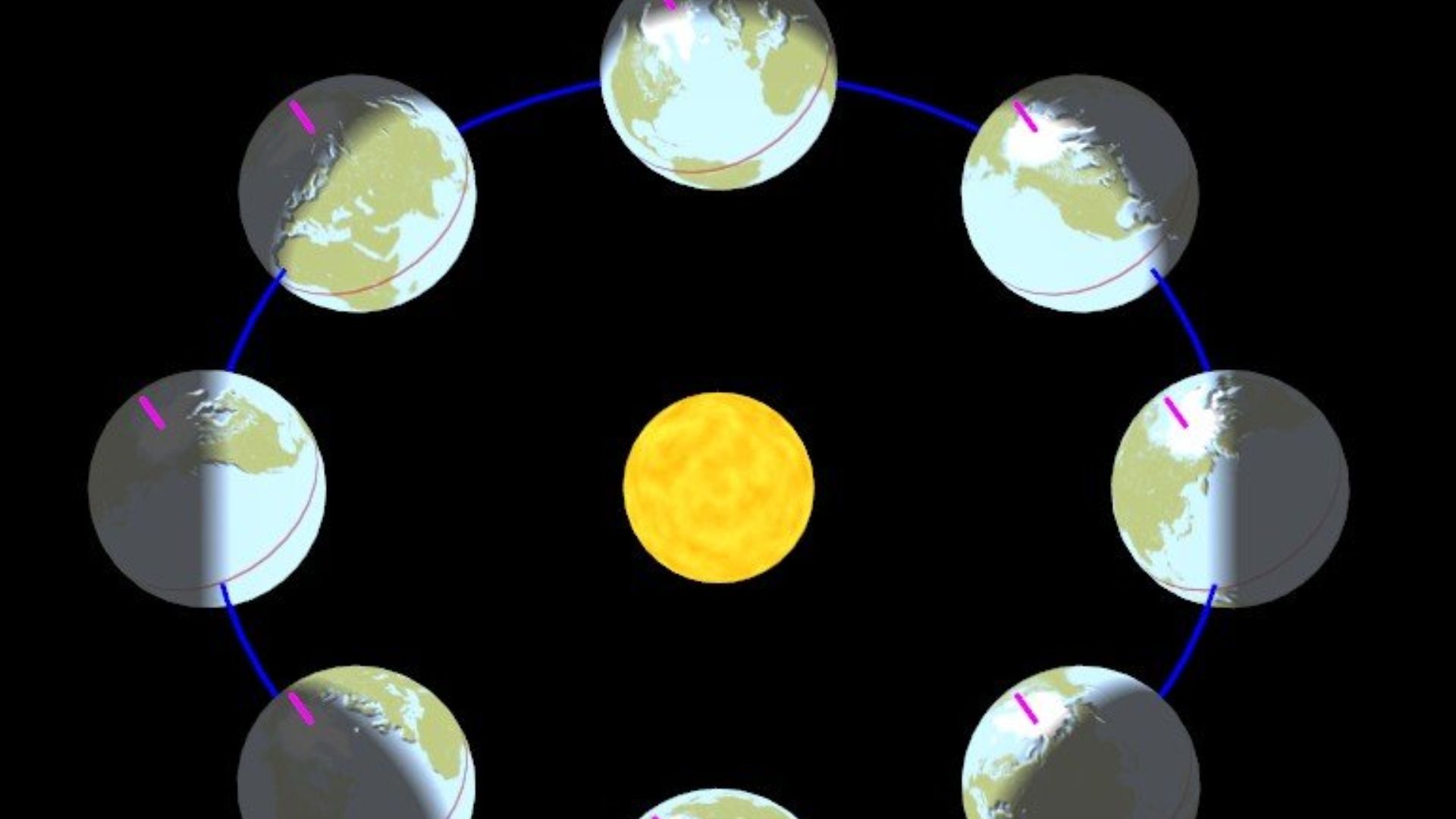

Understanding Earth's Natural Tilt

Our planet isn't upright—it leans at about 23.4° relative to its orbit. This tilt decides how sunlight falls across the planet and creates seasons. The angle stays fairly stable and shifts only very slowly over tens of thousands of years due to natural astronomical cycles.

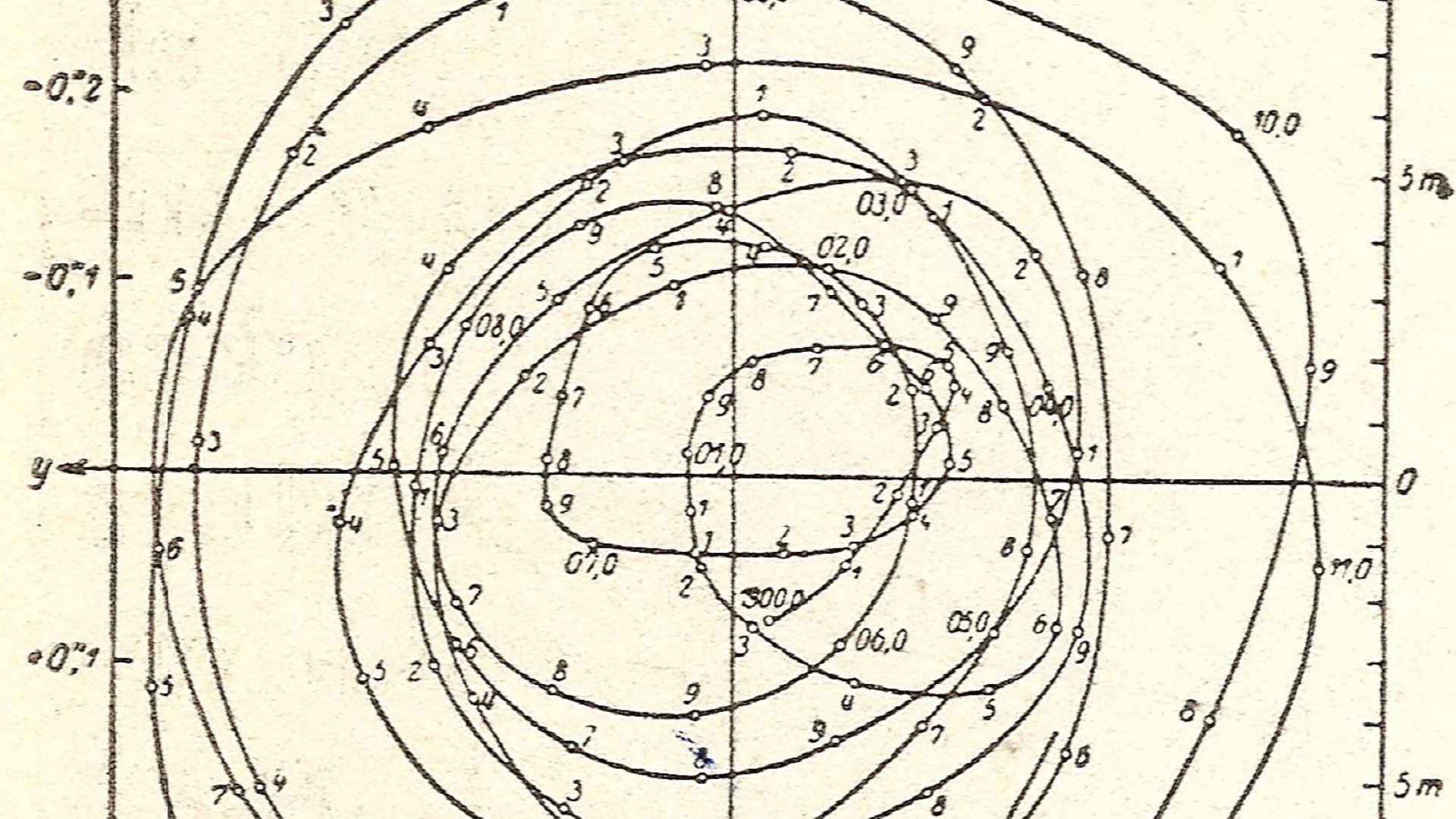

The Chandler Wobble Explained

Earth naturally wobbles as it spins. The Chandler wobble is a small circular shift of the North Pole about a few meters wide every 14 months. It occurs because Earth isn't perfectly rigid or evenly balanced. Scientists track it as part of normal rotational behavior.

Accepting for Value, Wikimedia Commons

Accepting for Value, Wikimedia Commons

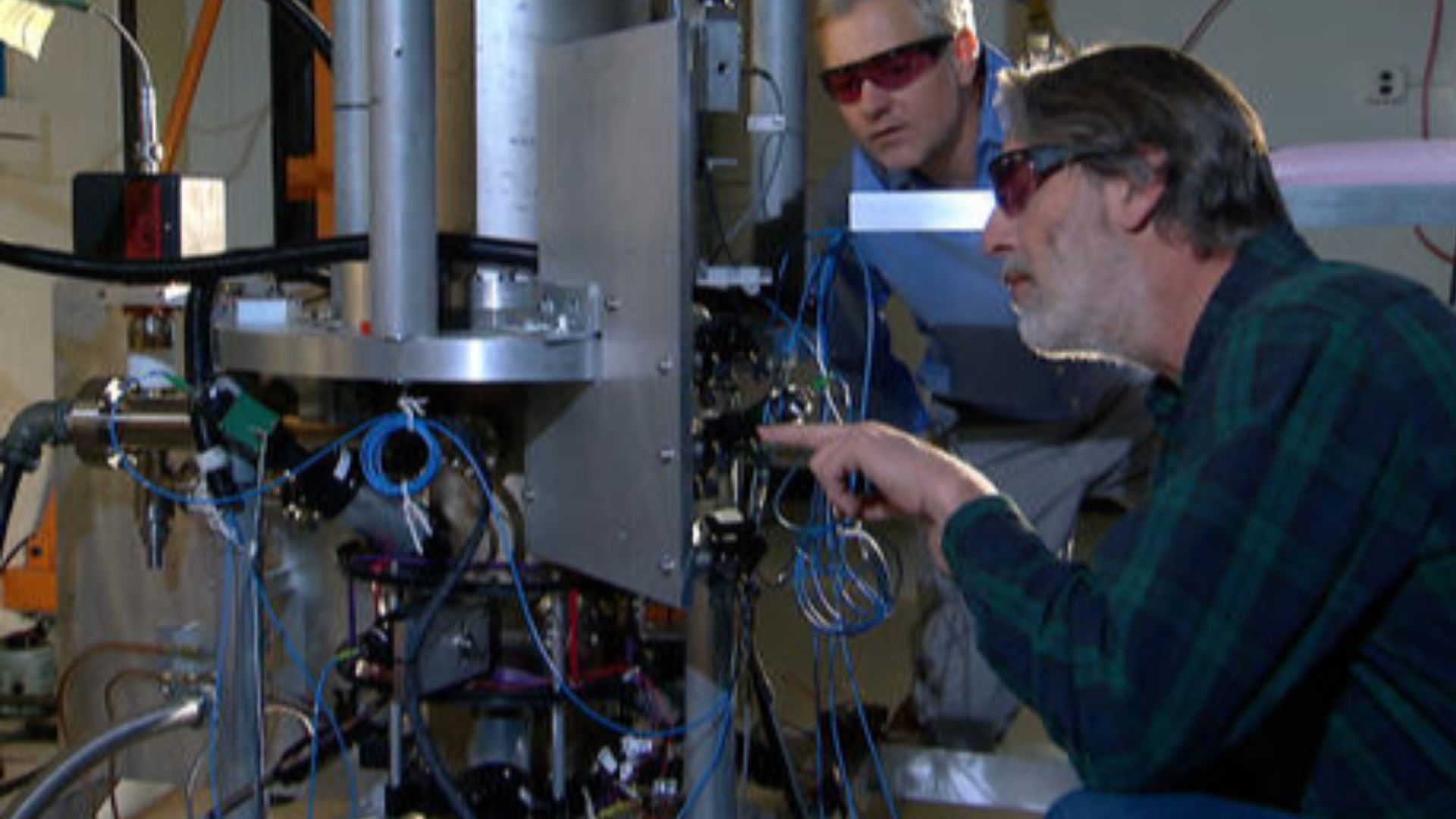

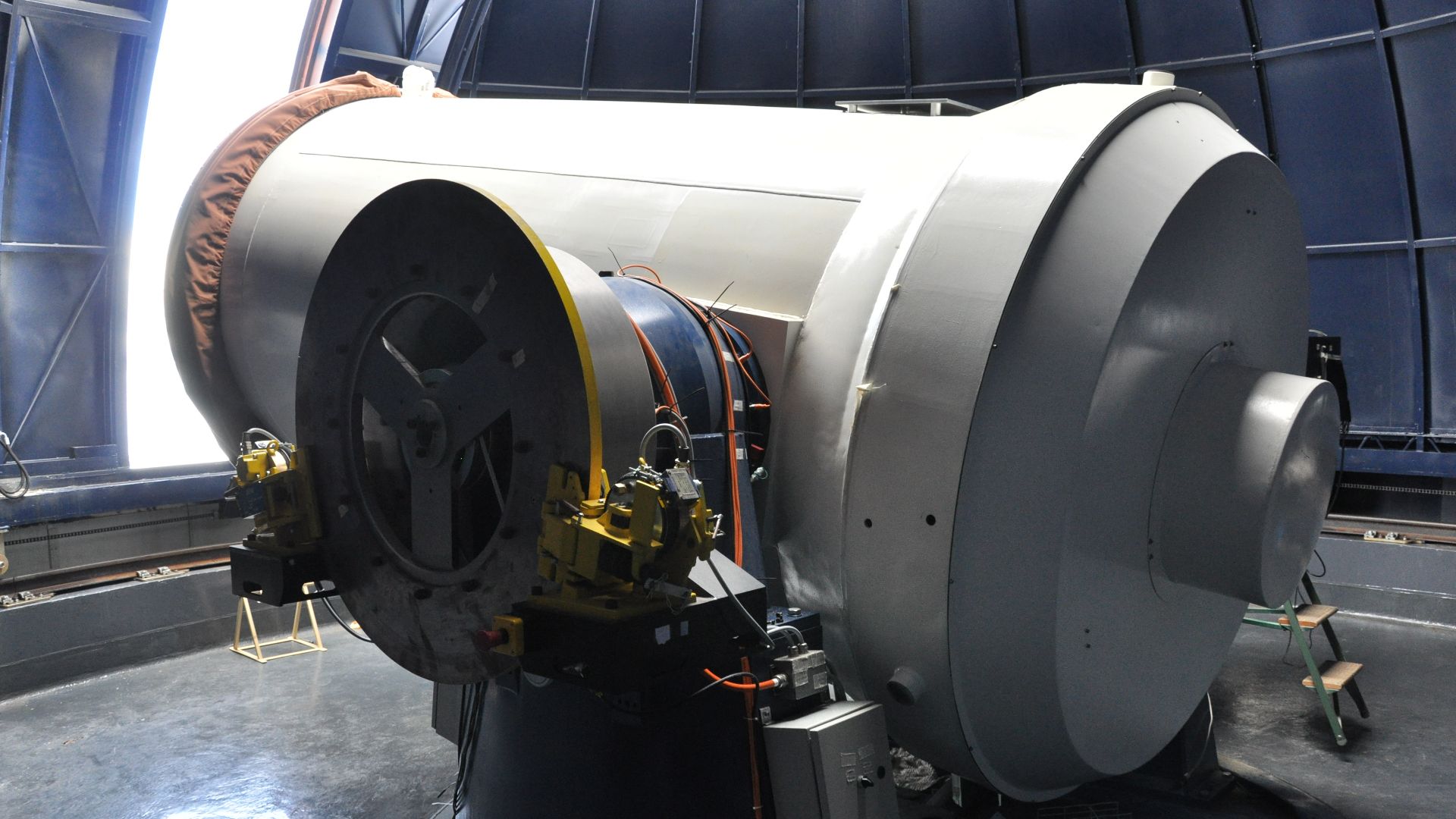

How Scientists Track These Movements

Scientists track Earth's rotation using satellite geodesy, laser-ranging systems, radio telescopes, and astronomical observations. These tools monitor tiny changes in rotation and wobble, along with pole position, with accuracy down to millimeters. The data feeds into Earth Orientation Parameters used worldwide.

H. Raab (User:Vesta), Wikimedia Commons

H. Raab (User:Vesta), Wikimedia Commons

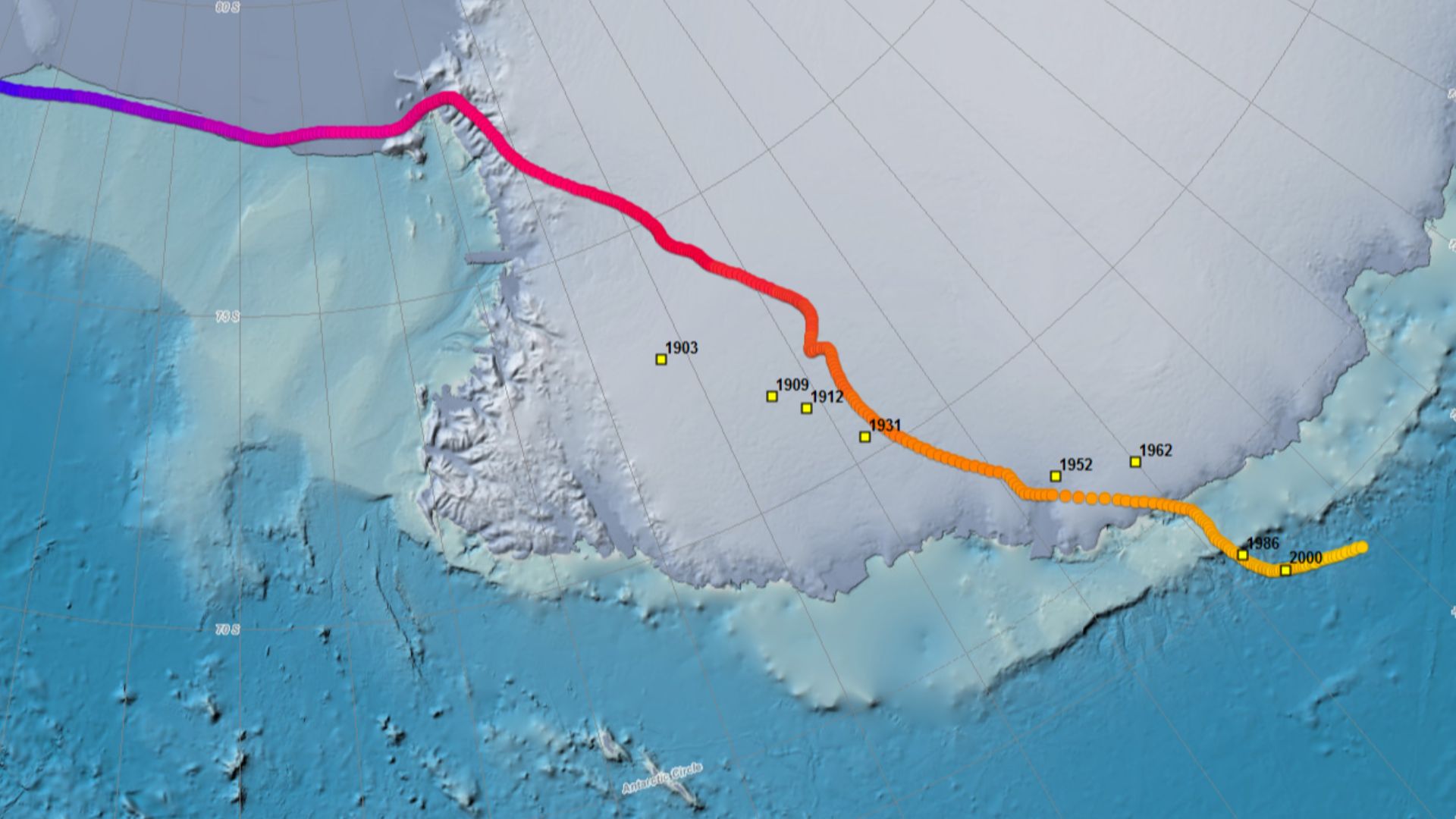

Why This Particular Shift Stands Out

The rotational pole naturally drifts a few centimeters each year. But between 1993 and 2010, the movement accelerated and shifted direction more than expected. The 31.5-inch displacement over that period stood out compared to typical decadal patterns seen in earlier data.

Saperaud~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Saperaud~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Natural Internal Causes

Earth's interior never stays completely still. Slow mantle flow, shifting density patterns, and the movement of molten rock beneath the crust constantly redistribute mass deep within the planet. These processes cause slight polar motion over time, but they unfold gradually across centuries and millennia.

Daniel Aufgang, Wikimedia Commons

Daniel Aufgang, Wikimedia Commons

Natural Internal Causes (Cont.)

Large earthquakes add sudden jolts to this background movement. The 2004 Sumatra earthquake, for instance, slightly altered both day length and axis orientation in measurable ways. However, these dramatic events create only temporary effects. They're too small and too infrequent to account for the sustained directional shift scientists observed.

Michael L. Bak, Wikimedia Commons

Michael L. Bak, Wikimedia Commons

Gravitational Pull From Sun And Moon

The Sun and Moon constantly tug on Earth to create tides that subtly adjust rotation. These gravitational forces shift water and even Earth's crust by measurable amounts. While these effects are continuous, they follow predictable cycles and don't explain the recent unusual drift.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

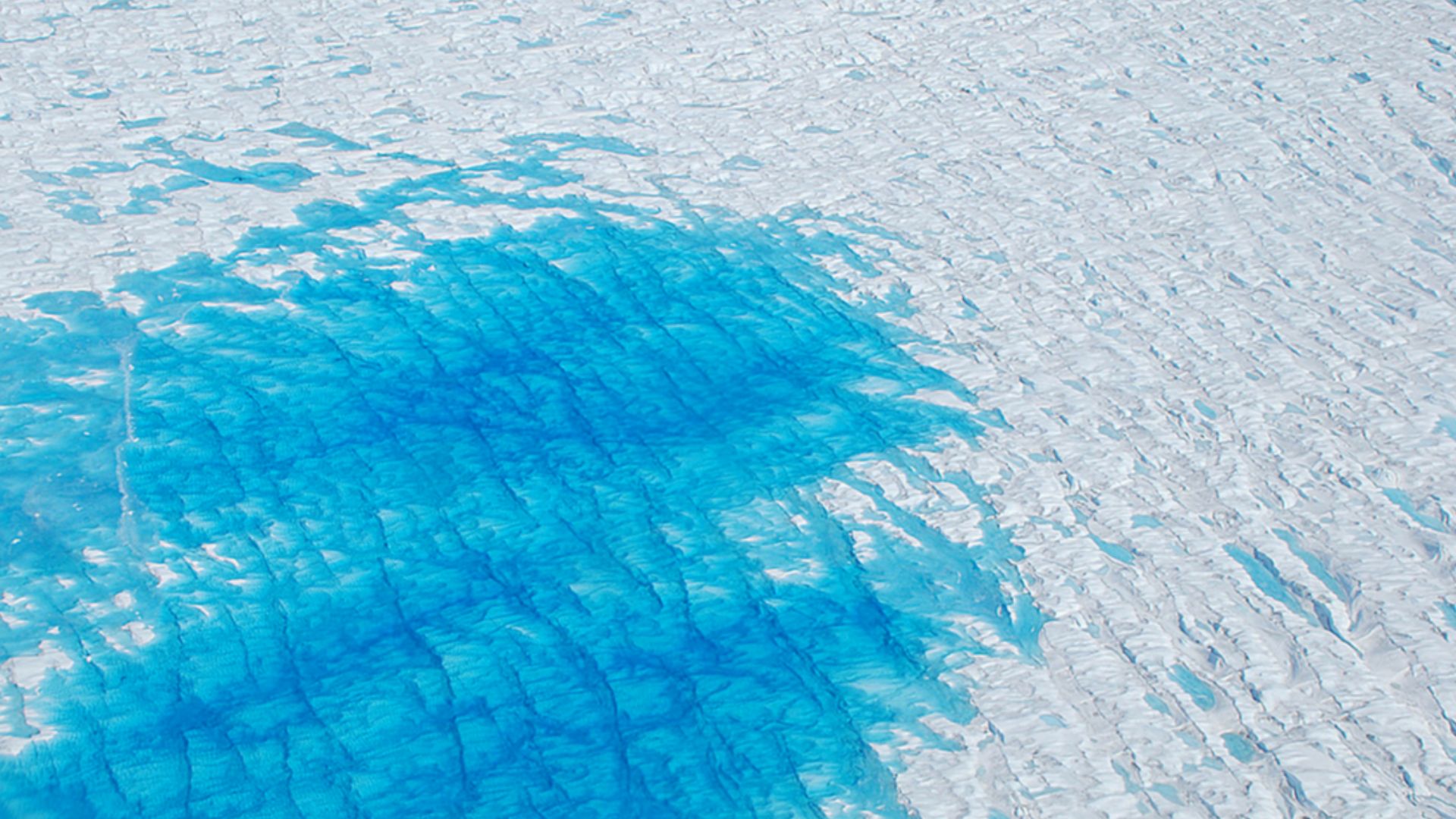

The Ice Melt Factor

Movement of water from melting glaciers and shifting precipitation relocates massive amounts of weight across the Earth. This redistribution changes the rotation slightly. Recent decades saw accelerated ice melt in Greenland and Antarctica, which contributed to long-term polar motion trends observed by scientists.

The Human Water Problem

Human activity moves enormous amounts of water. Groundwater pumping, dams, reservoirs, and irrigation all transfer mass across the planet. From 1993 to 2010, global groundwater extraction was high enough to measurably influence Earth's rotation once that water entered the oceans.

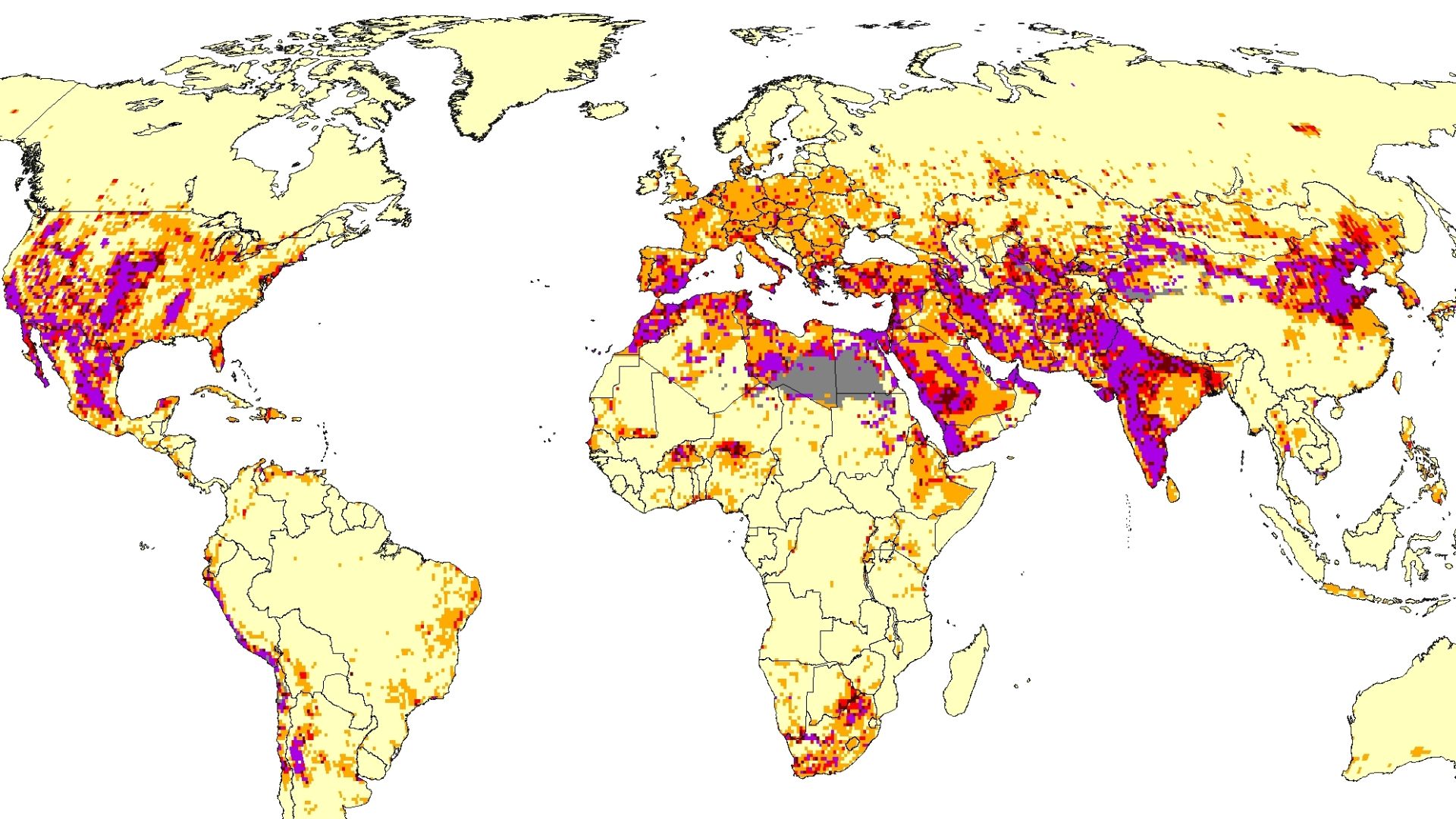

The Scale Of Groundwater Extraction

Scientists estimate that in those 17 years, humans pumped about 2,150 gigatons of groundwater. That's enough to fill roughly 860 million Olympic pools. Once this water reached the oceans, it added weight in places that pushed Earth's pole off its usual path.

John Poyser, Wikimedia Commons

John Poyser, Wikimedia Commons

Why Location Matters

Groundwater loss in mid-latitude regions—like western North America and northwestern India—has a stronger effect on Earth's wobble. These areas sit in zones where shifting mass influences rotation more directly. This makes their groundwater pumping a major driver of the unexpected pole movement.

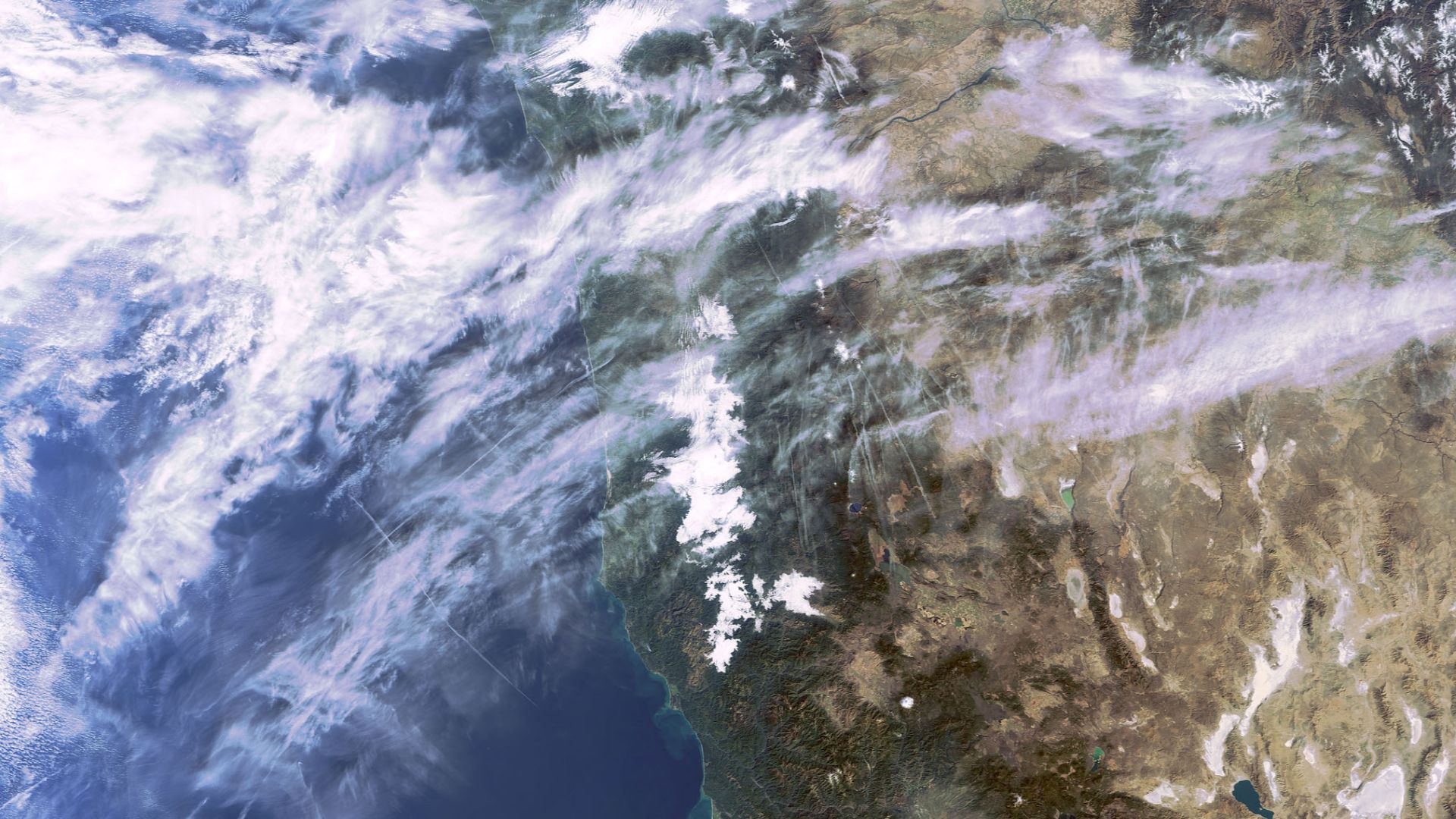

Envisat satellite, Wikimedia Commons

Envisat satellite, Wikimedia Commons

Navigation Systems Feel The Impact

Tiny changes in Earth's rotation affect systems that rely on precise alignment. Satellite positioning, GPS accuracy, and astronomical observations all depend on stable Earth Orientation Parameters. Even small pole shifts can introduce measurable errors, which is why scientists monitor them so closely.

Timekeeping Precision Matters

Earth's rotation underpins how we measure time. Even tiny pole shifts can affect the length of a day by milliseconds. Atomic clocks and leap seconds are used to keep civil time aligned. Monitoring these changes ensures calendars, navigation, and communication systems stay accurate.

The Axis Remains Stable

Despite the recent movement, Earth's axis remains stable on large scales. The 23.4° tilt hasn't changed significantly. Scientists view the 31.5-inch shift as a sign of mass redistribution, not a sign of long-term tilt instability or runaway changes that would threaten the planet.

Gaël Gaborel - OrbisTerrae, Unsplash

Gaël Gaborel - OrbisTerrae, Unsplash

Seasonal Patterns Stay Intact

If Earth's axial tilt changed significantly, sunlight patterns would shift to alter seasonal intensity by latitude. The recent axis movement does not affect this distribution. Scientists monitor tilt because even small long-term changes influence how regions warm or cool seasonally over geological time.

Long-Term Climate Connections

Past variations in tilt contributed to shifts in storm paths, monsoon strength, and ice sheet behavior. While the current 31.5-inch shift doesn't change tilt, scientists track these dynamics to understand how future obliquity shifts may reshape rainfall patterns and temperature extremes.

Basile Morin, Wikimedia Commons

Basile Morin, Wikimedia Commons

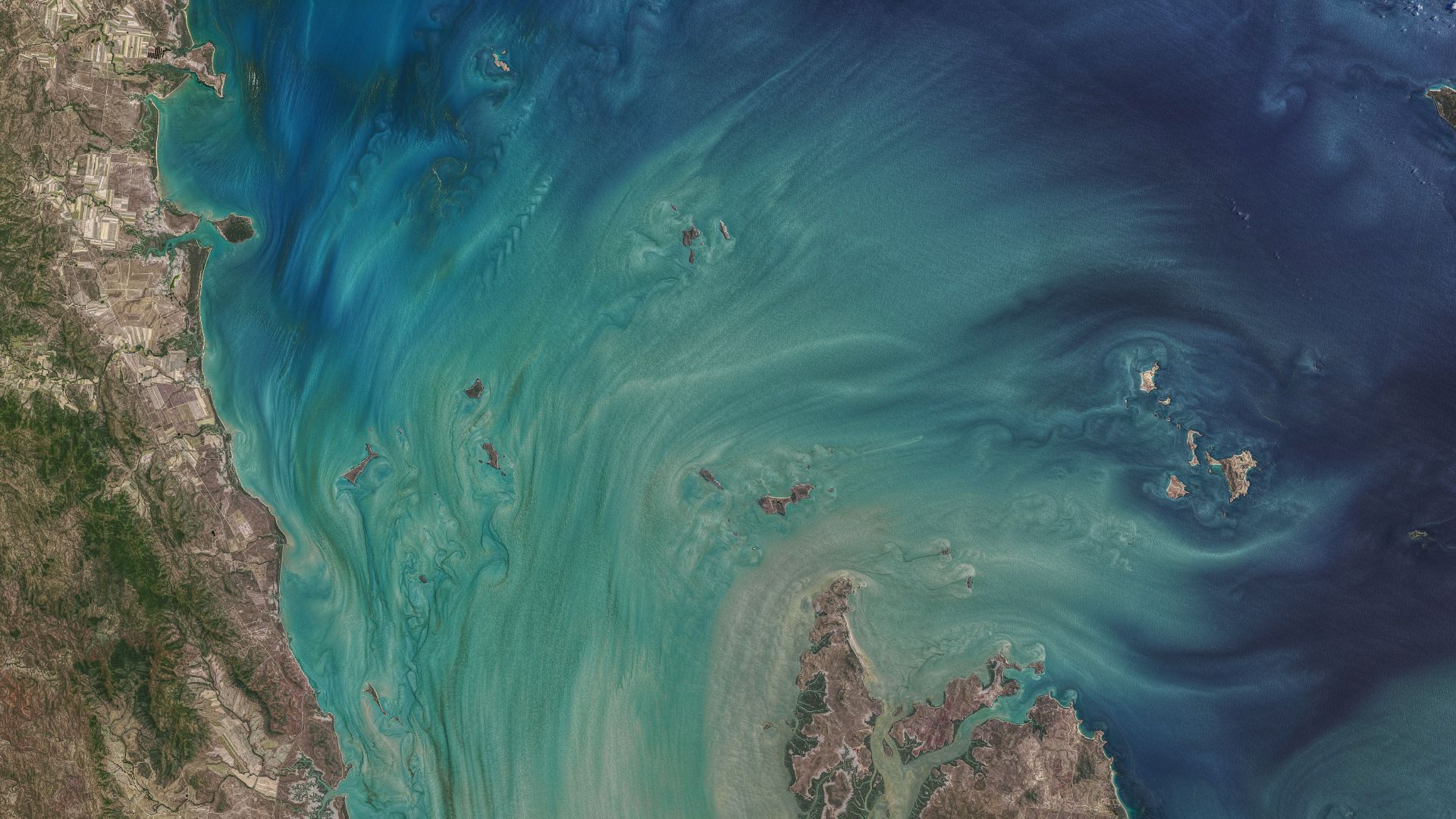

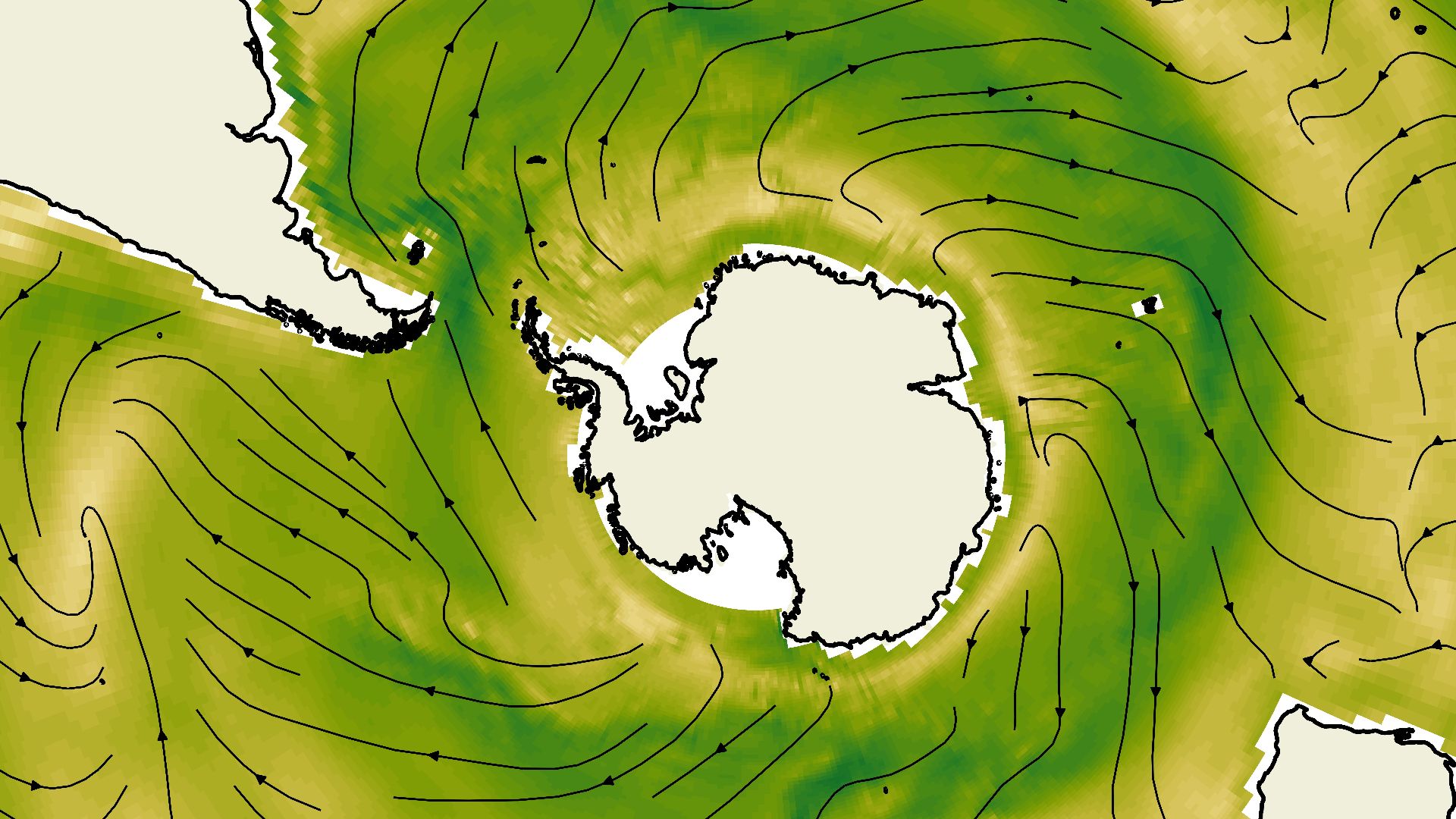

Ocean Current Sensitivity

Earth's tilt influences how sunlight heats oceans. Over geological timescales, tilt shifts can alter major currents like the Gulf Stream or Antarctic Circumpolar Current. The recent pole drift won't change these systems; still, it highlights how sensitive oceans are to mass movement.

Ecosystem Timing Over Time

Small changes in Earth's tilt influence daylight length over long periods. This affects migration, breeding, flowering, and feeding cycles in many species. The present shift doesn't alter daylight timing, but natural obliquity changes have historically impacted ecosystems across continents.

Scientific Debate Continues

Researchers continue evaluating how much of the recent drift comes from groundwater extraction versus natural processes. Multiple independent datasets and modeling approaches are being compared to confirm the magnitude of human-driven influence and refine uncertainties in the measurements.

Other Possible Explanations

Earth's pole can drift for short periods when natural conditions briefly shift the planet's weight, such as when ocean patterns adjust or air pressure systems move across continents. Sudden ice loss can add to this temporary motion. Scientists also check for measurement errors.

What The Future Might Hold

Scientists aren't predicting dramatic consequences from this single shift, but they view it as an early indicator. If groundwater depletion and ice melt continue accelerating, future wobble patterns may become stronger and harder to predict. Monitoring becomes increasingly important.

Claudia Herbert, Petra Döll, Wikimedia Commons

Claudia Herbert, Petra Döll, Wikimedia Commons

What Scientists Are Watching Next

Tracking how Earth’s mass and motion shift helps predict where the rotational pole is heading. New satellite technology is sharpening these measurements, giving researchers a clearer picture of how the planet reacts to both natural processes and human-driven changes.

Why This Matters To Everyone

This shift reminds us that human activity can influence planetary-scale systems in measurable ways. Groundwater extraction seemed like a local issue, but its effects rippled globally. Understanding these connections helps scientists prepare for future changes and encourages more sustainable resource management worldwide.