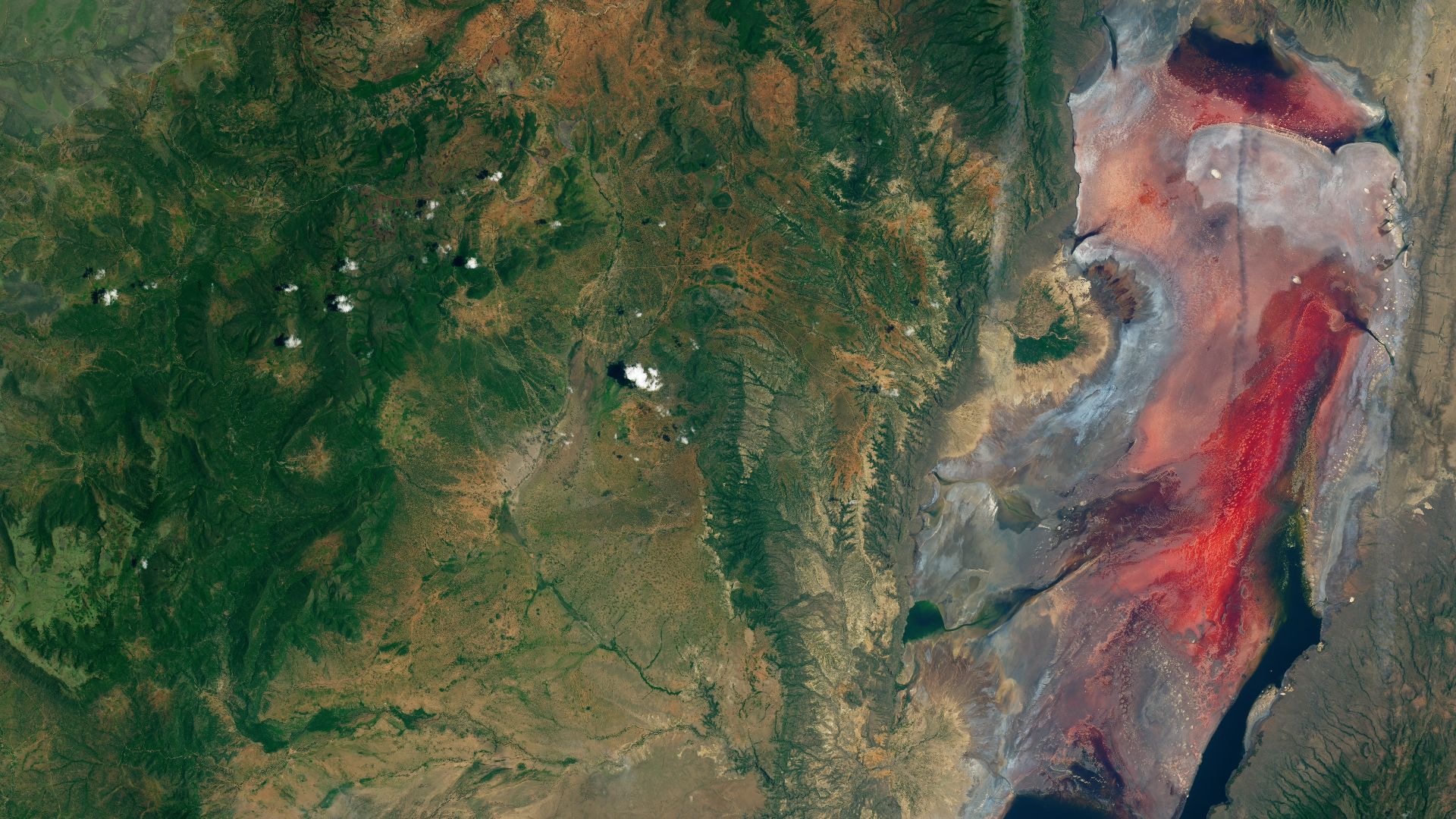

Some stories sound made up until you see the evidence lined along the shore. In northern Tanzania, Lake Natron transforms dead animals into eerie, statue-like forms that look carved rather than preserved. The scene feels otherworldly, yet the process behind it is grounded in science.

A Lake That Preserves The Dead Instead Of Letting Them Decay

Lake Natron sits in a tectonic valley where volcanic activity shapes everything from the soil to the water chemistry. The lake reaches temperatures above 120 degrees Fahrenheit during peak heat. Its surface shimmers like metal, and its shallows bite your skin with alkaline strength strong enough to burn. These conditions create an environment where almost nothing thrives.

Because water flowing into the lake carries sodium carbonate and other minerals from nearby volcanic deposits, Natron becomes highly caustic. When birds or bats collide with the lake’s surface or die near the shoreline, the minerals coat their bodies quickly. Feathers stiffen, skin hardens, and the shapes lock into place. The result looks sculpted, not natural, especially when sunlight reflects off the crust. That visual shock is what leads people to compare the remains to stone.

While the effect appears magical, the chemistry follows predictable rules. Mineral saturation and heat accelerate preservation, stopping decay before scavengers or microbes can break down the bodies. The process mirrors the ancient Egyptian use of natron salts in mummification, though Natron accomplishes it without human intervention. For researchers, it offers a rare look at how extreme environments manipulate organic matter.

The lake’s harsh nature also affects species distribution across the region. Only a handful of organisms can manage the alkalinity, and this includes certain algae and hardy invertebrates. Flamingos feed on the algae and depend on the lake’s isolation for nesting. Their survival highlights how some animals adapt to conditions that repel nearly everything else.

Where Science Meets The Uncanny

Visitors describe a strange stillness around Lake Natron, partly because the heat ripples through the air and partly because the lake’s color shifts from red to orange during algae blooms. Those colors come from microorganisms that thrive in water most animals avoid. When the wind drops, the shoreline goes silent except for distant flamingos. That contrast—the living beside the preserved—adds a surreal note to the terrain.

Photographers who have documented the lake’s preserved animals note how natural calcium deposits create an illusion of stone. Wings stretch out as if frozen mid-flight, and heads tilt in lifelike positions.

Alkaline lakes like this exist elsewhere, but none match Natron’s combination of heat, mineral saturation, and isolation. Understanding its chemistry helps researchers predict how life adapts near volcanic areas. It also offers clues about how certain fossils formed in ancient alkaline basins.

This research matters for Earth and history studies. Past climates left behind lakes with mineral levels similar to Natron, and their fossils show signs of rapid preservation.

A Natural Wonder With A Dangerous Edge

Three distinct traits set Lake Natron apart from other extreme lakes:

High Alkalinity: Comparable to industrial cleaning solutions.

Extreme Heat: Water temperatures can exceed 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

Mineral-Driven Preservation: Bodies dry and harden before decomposition begins.

Together, these traits create a shoreline that feels equal parts science lab and mythic setting. You see beauty, danger, and geological history playing out in real time. The environment tests the limits of life, yet it also supports flamingos whose breeding cycles rely on the lake’s inhospitable nature. Predators stay away, giving the birds a refuge few species can use.

Researchers continue monitoring Natron because climate shifts may alter water levels and mineral concentrations. Lower water levels increase salinity. Higher levels dilute it. Either change affects the algae that flamingos depend on. Tracking these shifts helps scientists understand how small environmental changes ripple through tightly balanced ecosystems.

The lake also raises questions about human impact. Increased development in the region and rising temperatures could reshape the lake’s chemistry. Those changes threaten its role as the most important flamingo breeding site in East Africa. Protecting it isn’t about preserving eerie statues; it’s about safeguarding a habitat built around extreme conditions that only certain species can handle.

The next time you hear someone mention a lake that “turns animals to stone,” you’ll know the real story. It isn’t fantasy. It’s chemistry, heat, geology, and biology working together in one of the harshest, most fascinating places on the continent.