The strange map error behind modern territorial thinking

A backwards map inside a 1525 Bible traveled farther than its creator ever expected. Generations accepted it as truth, which allowed a simple error to reshape ideas about land and authority.

Could A Single Printing Error Really Change How We See The World?

A printing mistake from 1525 did more than distort a picture. It introduced European readers to a visualized Holy Land at a time when maps carried growing authority. Understanding how one flawed image circulated helps explain how early printed materials shaped public imagination long before accurate geographic knowledge became widely available.

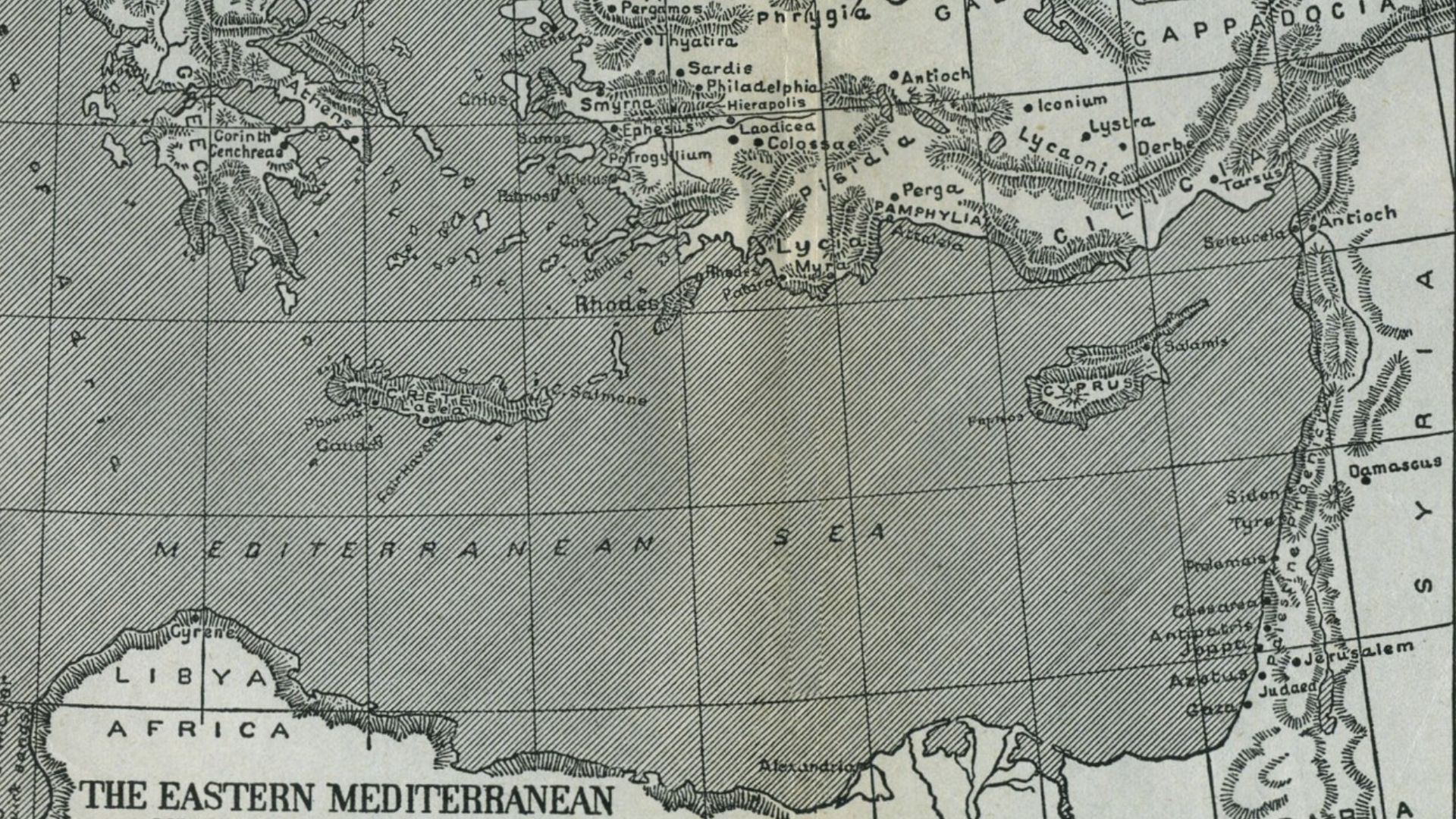

Before Maps Made The Bible “Real”

Before printed Bibles included illustrations, most Europeans experienced scripture as spoken stories or handwritten texts without spatial clues. Reliable geographic information about the Eastern Mediterranean was rare, which left people to imagine biblical settings abstractly.

The original uploader was Athrash at English Wikibooks., Wikimedia Commons

The original uploader was Athrash at English Wikibooks., Wikimedia Commons

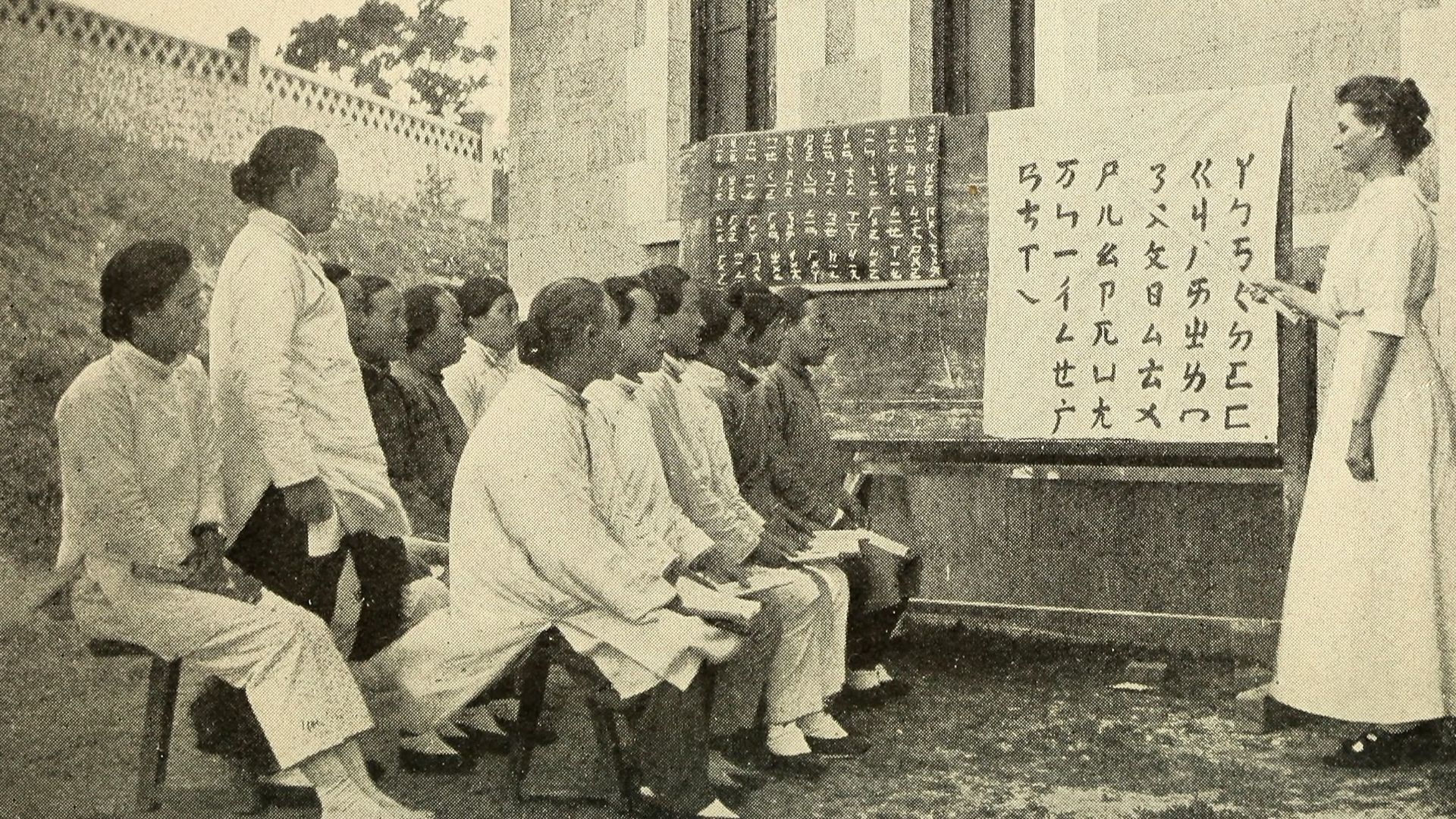

Printers Began Adding Images To Sacred Texts

By the early sixteenth century, printers realized that illustrations helped readers understand dense material and increased interest in new editions. Visual elements also lent a sense of authenticity in an era of expanding literacy. Adding maps to scripture reflected a broader cultural shift toward grounding ancient narratives in recognizable, physical space.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Froschauer’s Workshop And The Rise Of Mass-Produced Scripture

Christopher Froschauer’s Zurich press became influential during the Reformation, producing large quantities of vernacular Bibles for a rapidly growing readership. His editions reached regions with limited access to printed scripture. That wide distribution meant any visual feature, including a map, shaped public understanding before scholars had the tools to recognize errors.

The Map That Went Wrong Before Anyone Noticed

The 1525 Old Testament edition featured a map attributed to Lucas Cranach the Elder, accidentally reversing the Holy Land so the Mediterranean appeared on the wrong side. Because few readers possessed trustworthy geographic knowledge, the mistake passed unchallenged.

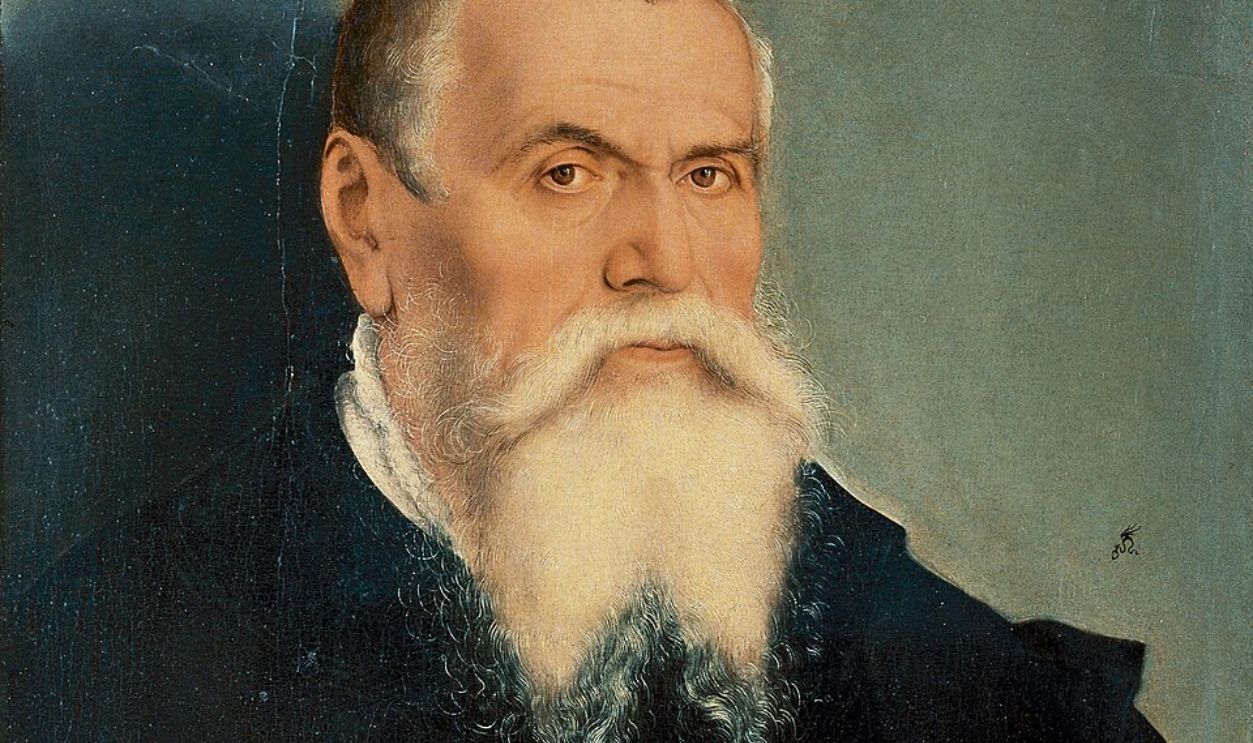

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Wikimedia Commons

Lucas Cranach the Younger, Wikimedia Commons

A Flipped Coastline Slipped Past Scholars And Readers

Geographic expertise in sixteenth-century Europe was limited, and most scholars relied on inherited medieval maps that varied widely in accuracy. With few standardized references, even trained readers overlooked the reversed coastline.

Seeing The Holy Land Through A New, Distorted Lens

For many Europeans, this printed map offered a first visual encounter with biblical stories. Its reversed layout subtly reshaped how readers imagined journeys, cities, and boundaries described in scripture. Because maps were viewed as authoritative tools, the distortion quietly influenced how people connected sacred narratives to the physical world.

Religious Imagination Met Early Cartography

Early cartographers blended limited firsthand knowledge with symbolic traditions inherited from medieval mapmaking. As printers inserted these images into Bibles, religious imagination and emerging geographic science began to overlap. This meeting point created a powerful effect: believers started treating spiritual accounts as anchored to real terrain, even when images were flawed.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Turning Biblical Stories Into A Place You Could Point To

Maps transformed abstract narratives into spatial experiences and gave readers a sense that biblical events unfolded in identifiable locations. This shift encouraged people to picture scripture as history rooted in physical landscapes. The newfound tangibility strengthened emotional connection and subtly guided how communities interpreted ancient texts within a recognizable geographic framework.

Aleksander Lauréus, Wikimedia Commons

Aleksander Lauréus, Wikimedia Commons

Visuals Carried More Authority Than Words

In an era when literacy was expanding but not universal, images communicated ideas quickly and carried an air of certainty. A map’s clarity suggested factual reliability, even when its information was incomplete. Because visuals bypassed lengthy explanations, they shaped understanding more directly than text.

Reshaping The Mental Image Of Sacred Space

Once the reversed map circulated, it influenced how readers pictured the locations mentioned in scripture. Physical orientation mattered less than the impression of solidity the map provided. Over time, this flawed visual became a mental reference point.

Zoltan Kluger, Wikimedia Commons

Zoltan Kluger, Wikimedia Commons

Readers Absorbed A New Way To Picture Land

As printed Bibles spread beyond clergy and scholars, ordinary readers encountered a structured vision of the Holy Land for the first time. The map introduced directional cues, boundaries, and spatial relationships that hadn’t existed in earlier imagination. This exposure normalized viewing biblical territory through a geographic framework rather than a symbolic tradition.

Ben White benwhitephotography, Wikimedia Commons

Ben White benwhitephotography, Wikimedia Commons

The Quiet Birth Of Territorial Thinking

By presenting sacred space as divided and measurable, the map encouraged readers to interpret land in terms of defined areas. This subtle shift paralleled broader European changes toward recognizing territory as something that could be claimed and administered.

L. Prang & Co. (publisher), Wikimedia Commons

L. Prang & Co. (publisher), Wikimedia Commons

Mapped Borders Began To Suggest Real Boundaries

Although the map depicted ancient regions, its structure mirrored early modern European ideas about territorial organization. Readers accustomed to seeing clear separations on biblical maps grew more comfortable applying similar logic to their own world. Over time, visualized boundaries contributed to evolving views about sovereignty and the legitimacy of controlled space.

San Jose (map), Hayden120 (retouch), Wikimedia Commons

San Jose (map), Hayden120 (retouch), Wikimedia Commons

Errors That Spread Faster Than Corrections In The Print Revolution

During the sixteenth century, printed mistakes traveled widely because distribution outpaced scholarly review. Once thousands of copies circulated, revising or retracting an error became nearly impossible. The flawed biblical map illustrates how misinformation persisted simply because printed material carried substantial credibility and reached audiences faster than corrective scholarship ever could.

A Flawed Map Traveling Across Europe’s Growing Information Networks

As printing centers multiplied, books circulated through trade routes linking cities, universities, and religious communities. The flawed map moved with them, reaching readers far from Zurich. Because few competing images existed, the map became a widely accepted reference.

Ludwig Deutsch, Wikimedia Commons

Ludwig Deutsch, Wikimedia Commons

The Unexpected Political Influence Of A Religious Illustration

Although created for devotional use, the map subtly reinforced emerging ideas about structured territory. By depicting regions as bounded and stable, it encouraged readers to imagine land as something that could be administered or claimed. This influence aligned with early modern shifts toward centralized authority and territorial governance.

Matson Collection, Wikimedia Commons

Matson Collection, Wikimedia Commons

Territorial Logic Seeped From Scripture Into Statecraft

Governments increasingly relied on maps to define jurisdiction and administer resources. Familiarity with structured biblical maps encouraged citizens and leaders to treat geography as an ordered space rather than loosely described regions. The map’s framework mirrored political developments and helped normalize territorial thinking across both religious interpretation and administrative practice.

Christian Schussele, Wikimedia Commons

Christian Schussele, Wikimedia Commons

Mapmakers Repeating Assumptions Baked Into The 1525 Design

Later artists and printers copied elements from earlier illustrations, assuming their predecessors had verified the information. As the reversed orientation reappeared in derivative works, the error gained further legitimacy. This chain of repetition reveals how early cartography sometimes preserved mistakes simply because reproducing existing images was easier than rechecking geographic accuracy.

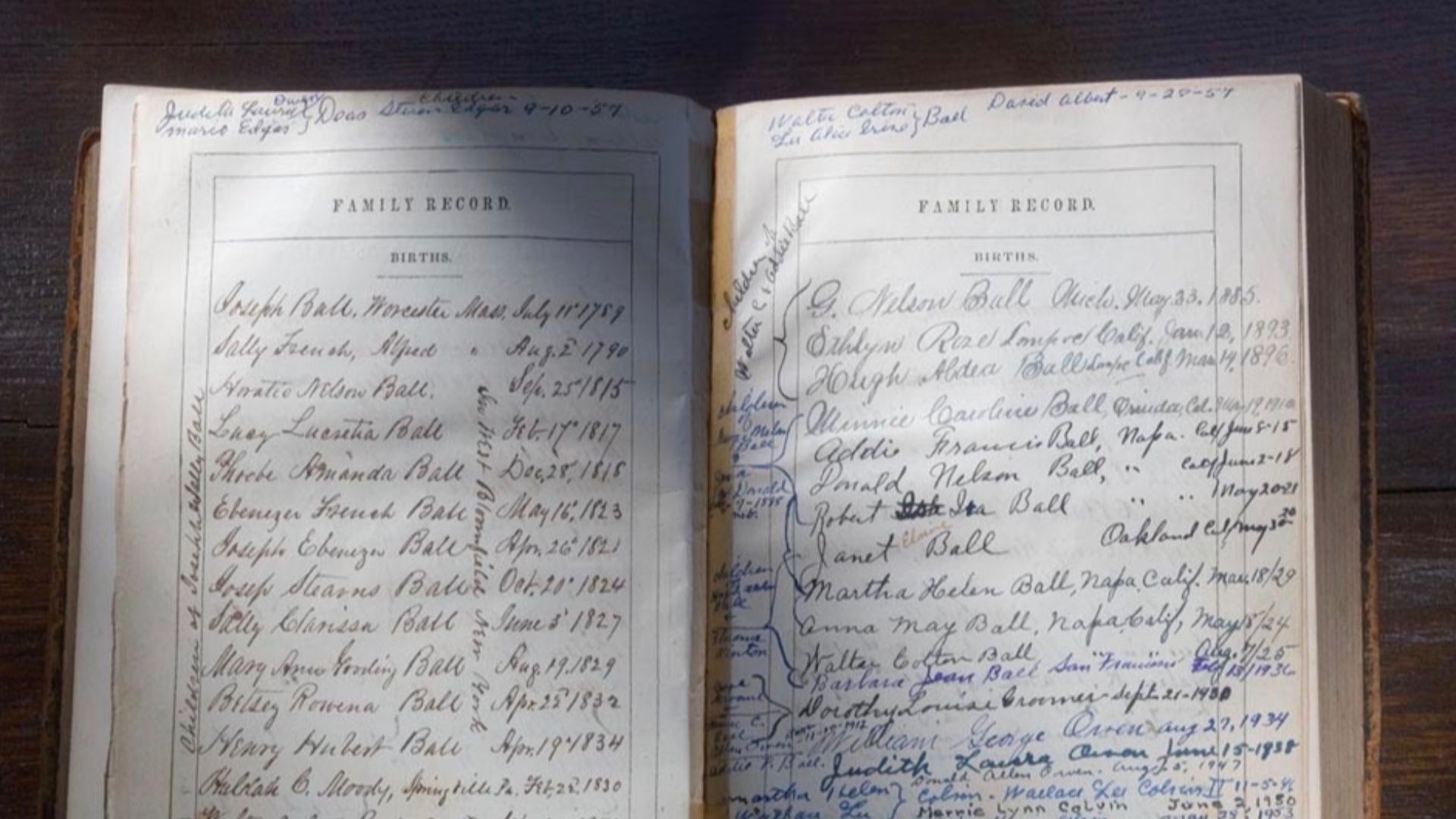

The Centuries-Long Endurance Of One Mistaken Image

Despite advances in exploration and cartography, the flawed map remained in circulation for generations. Many readers continued encountering it in family Bibles long after more accurate maps existed. Its longevity shows how influential early printed images became, especially when they appeared in sacred texts that shaped cultural understanding across centuries.

Modern Researchers Uncovering The Truth Behind The Map

Scholars examining early printed Bibles noticed the map’s reversed orientation and traced its origin to the 1525 edition. Their work highlighted how easily visual authority can overshadow accuracy. By comparing surviving copies and studying Cranach’s workshop practices, researchers clarified how the mistake occurred and why it persisted for so long.

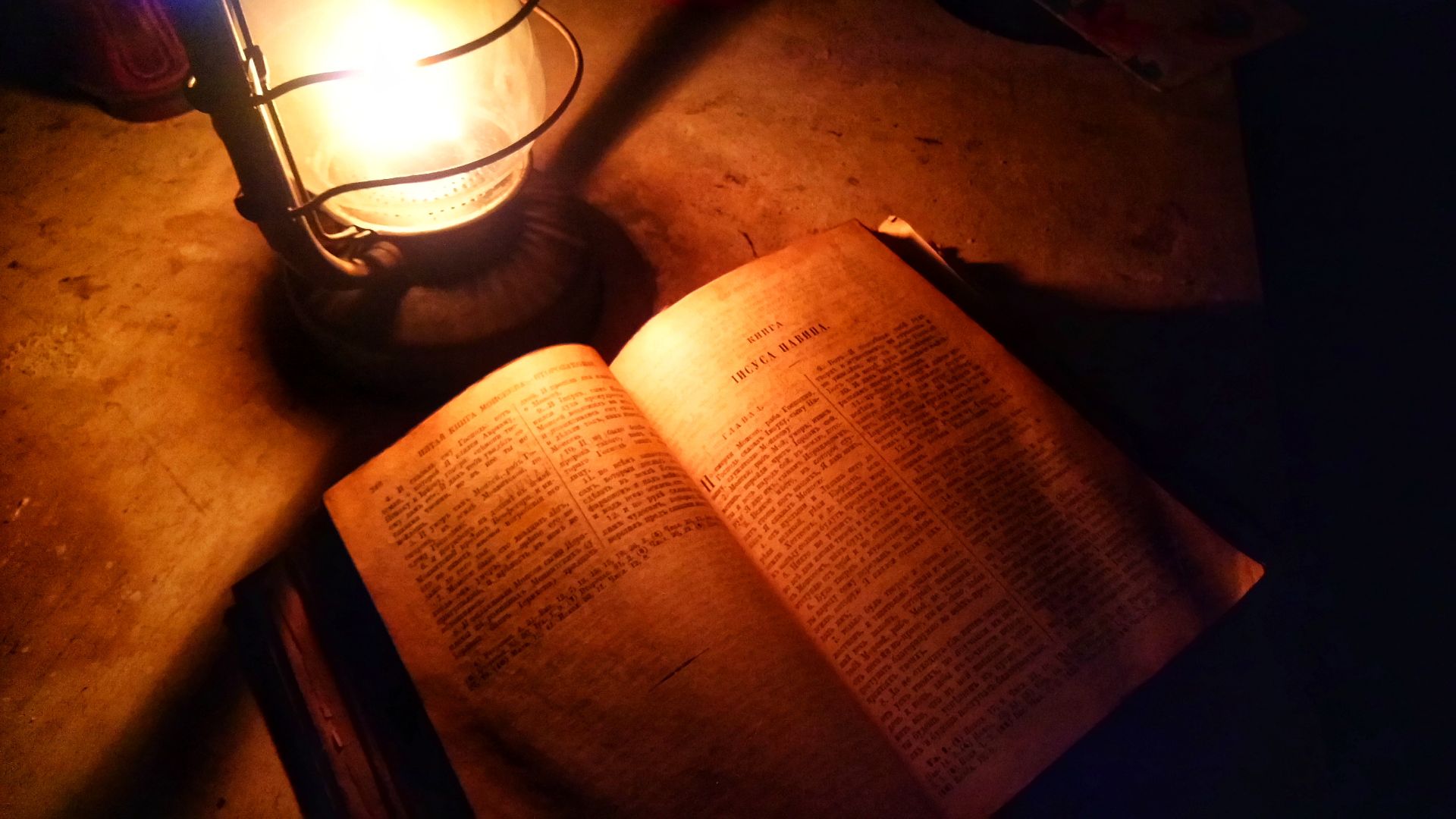

TyshkunVictor, Wikimedia Commons

TyshkunVictor, Wikimedia Commons

What This Error Reveals About The Origins Of Our Borders

The map’s influence shows how people gradually adopted a territorial mindset shaped by images rather than firsthand knowledge. Its structured divisions resembled later political borders, reminding us that modern ideas of nationhood grew from accumulated visual cues.

How Inherited Images Shape Our Sense Of Place

Most people form geographic understanding through pictures long before encountering detailed maps. Early printed illustrations worked the same way, offering a ready-made mental framework that shaped how readers imagined distant regions.

The Unsettling Power Of Believing What We Can Visualize

Once an idea appears in visual form, it gains an authority that words rarely match. Readers trusted the map because it felt concrete, not because it was correct. This dynamic continues today, reminding us that clarity in presentation can mask underlying errors.

A Modern World Built On Stories No One Meant To Tell

The map’s long influence shows how unintentional choices can shape cultural memory. A simple printing error helped nurture assumptions about territory and geographic certainty. Recognizing how these stories formed allows us to question inherited frameworks and understand the modern world as a product of both deliberate design and accidental inheritance.

naturalearthdata.com, Wikimedia Commons

naturalearthdata.com, Wikimedia Commons