Being Fed Lies

Hollywood films like Stagecoach (1939) and The Oregon Trail (1959) gave us a West that never quite existed. They were so focused on portraying noble settlers braving the unknown that they conveniently ignored the violent consequences of expansion.

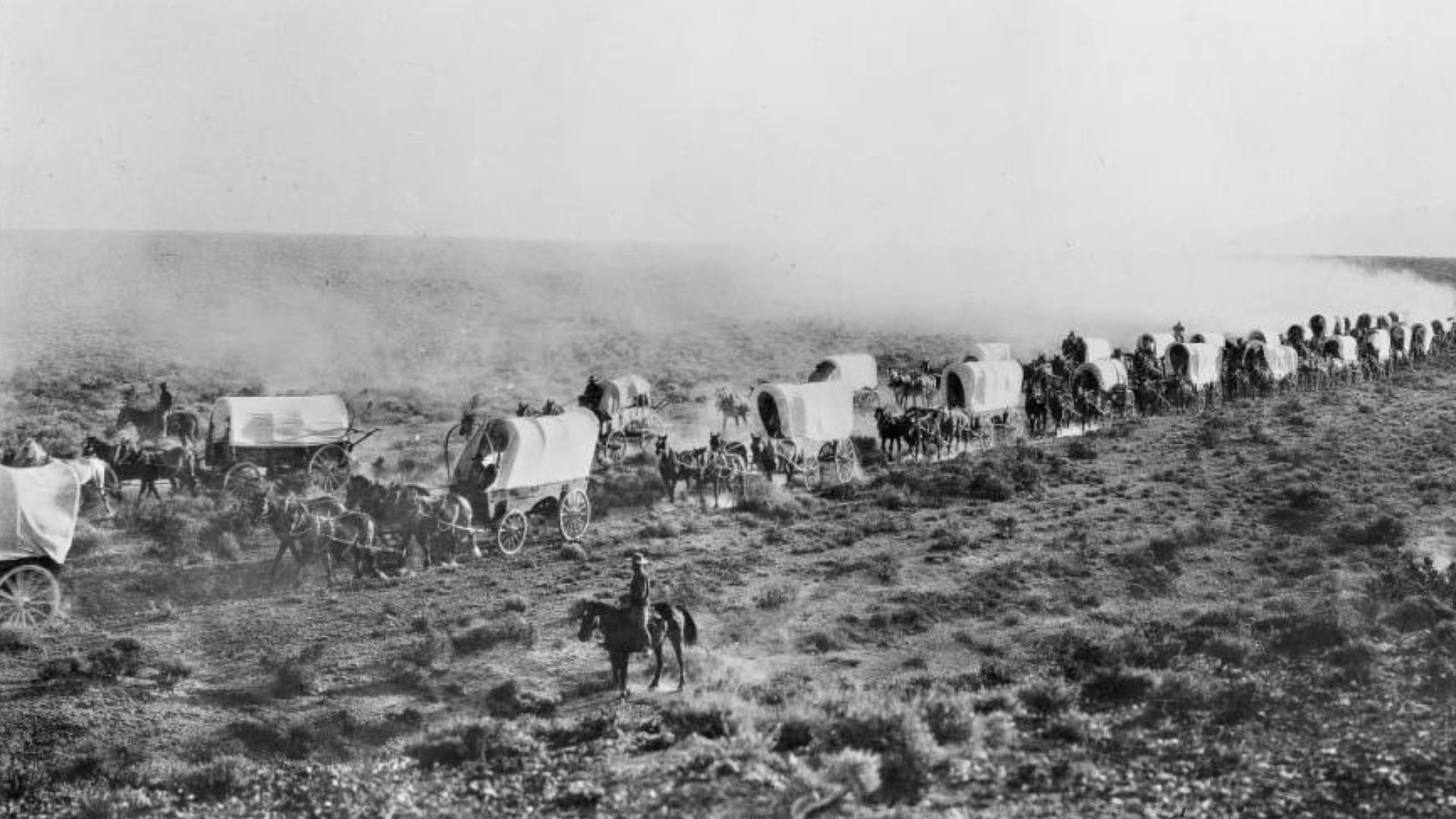

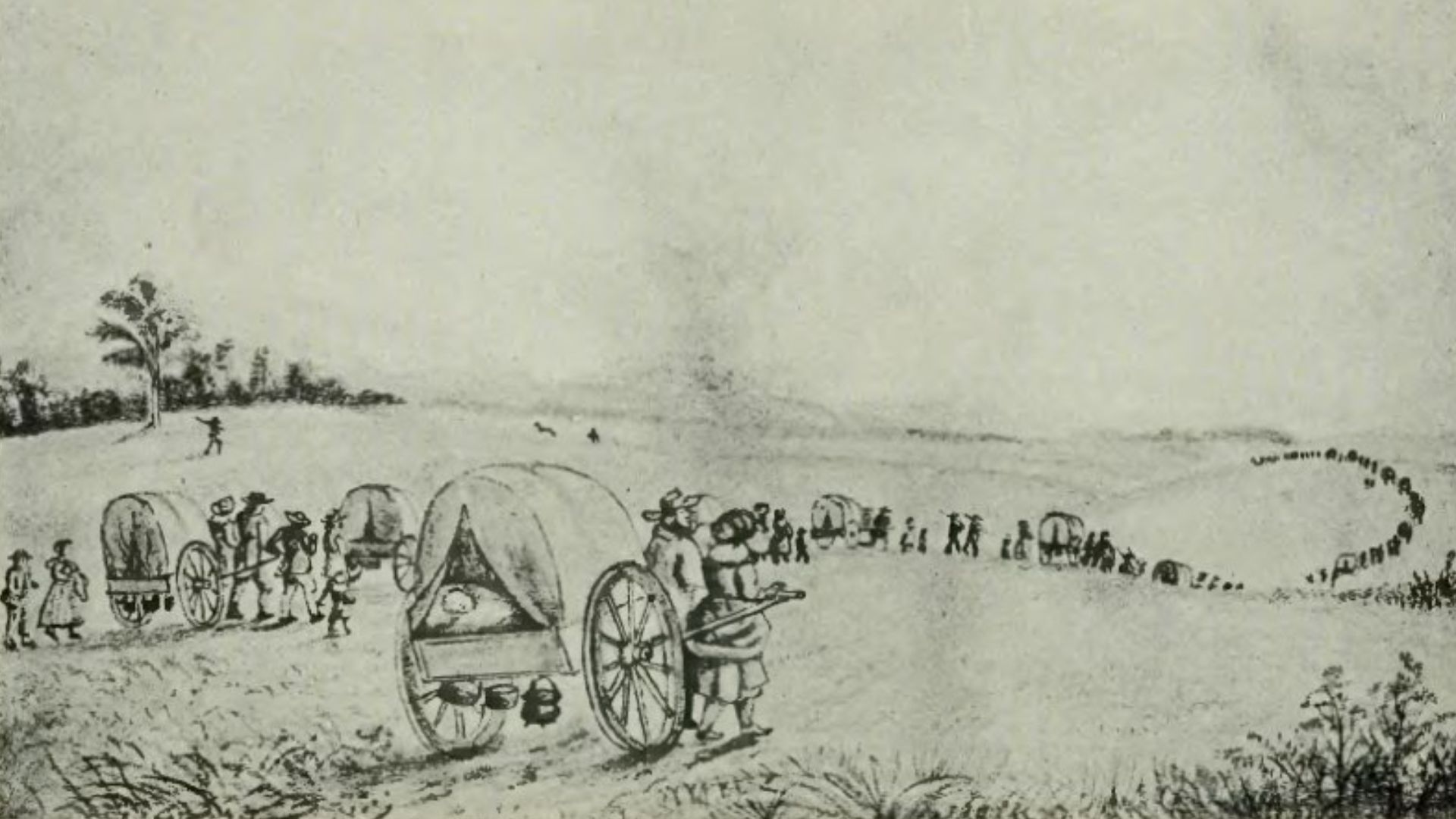

The Covered Wagon That Became A Symbol Of Hope

Covered wagons—those canvas-topped vehicles that came to define the era—were not nearly as romantic as they appear in the movies. Known as prairie schooners, they were essentially modified farm wagons, made to carry as much as 2,500 pounds across rough terrain. And over time, the covered wagon came to represent transformation.

B.D.'s world from Monroe, Washington, United States, Wikimedia Commons

B.D.'s world from Monroe, Washington, United States, Wikimedia Commons

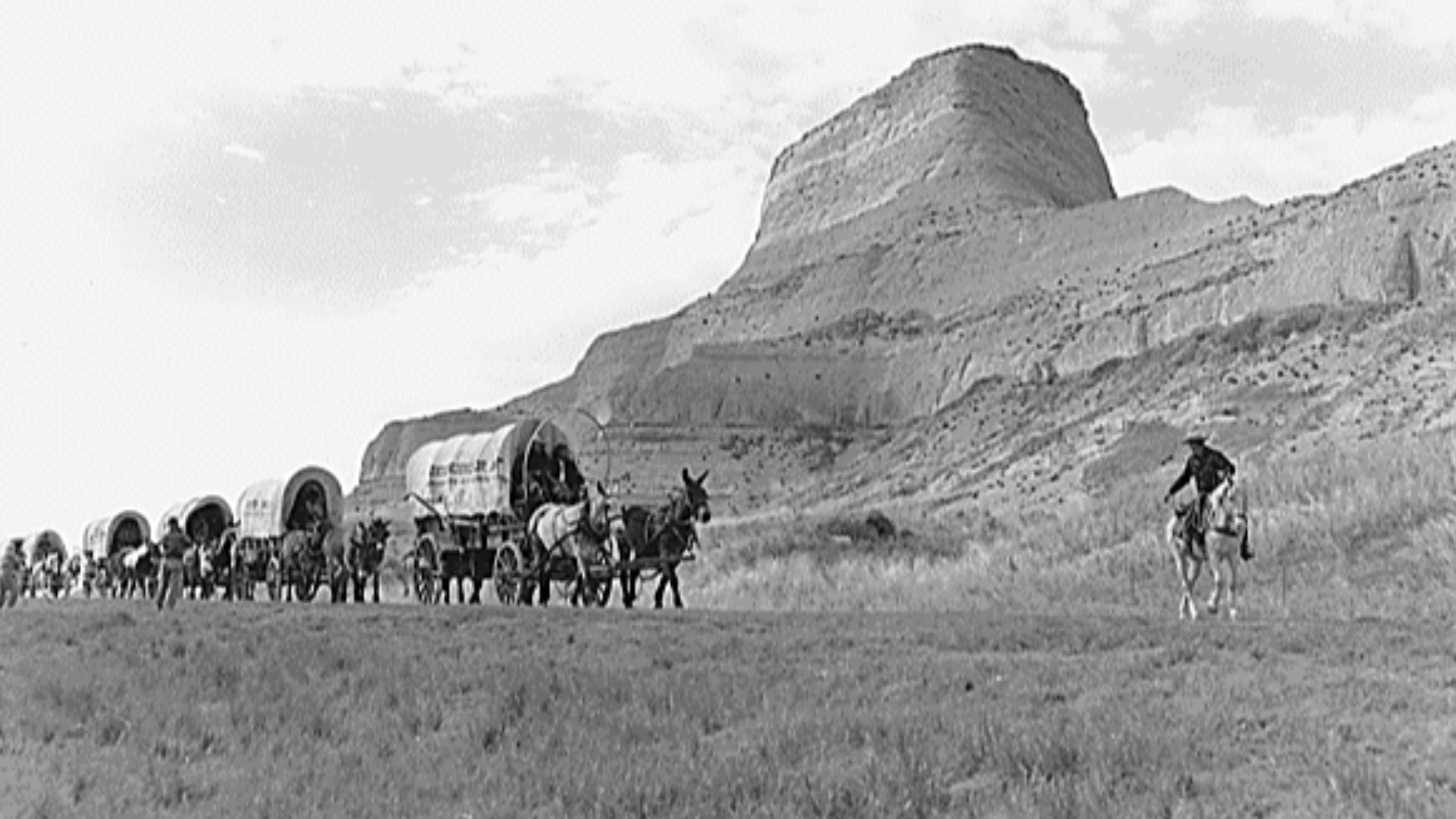

Four To Six Months On Foot Across Two Thousand Miles

The journey westward was long and unforgiving. It typically lasted four to six months and could stretch up to 2,000 miles. Traveling inside the wagon with no suspension meant that passengers were constantly jostled, which led many to walk beside the wagon rather than endure the rough ride.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Crossing Rivers And Mountains With Lives On The Line

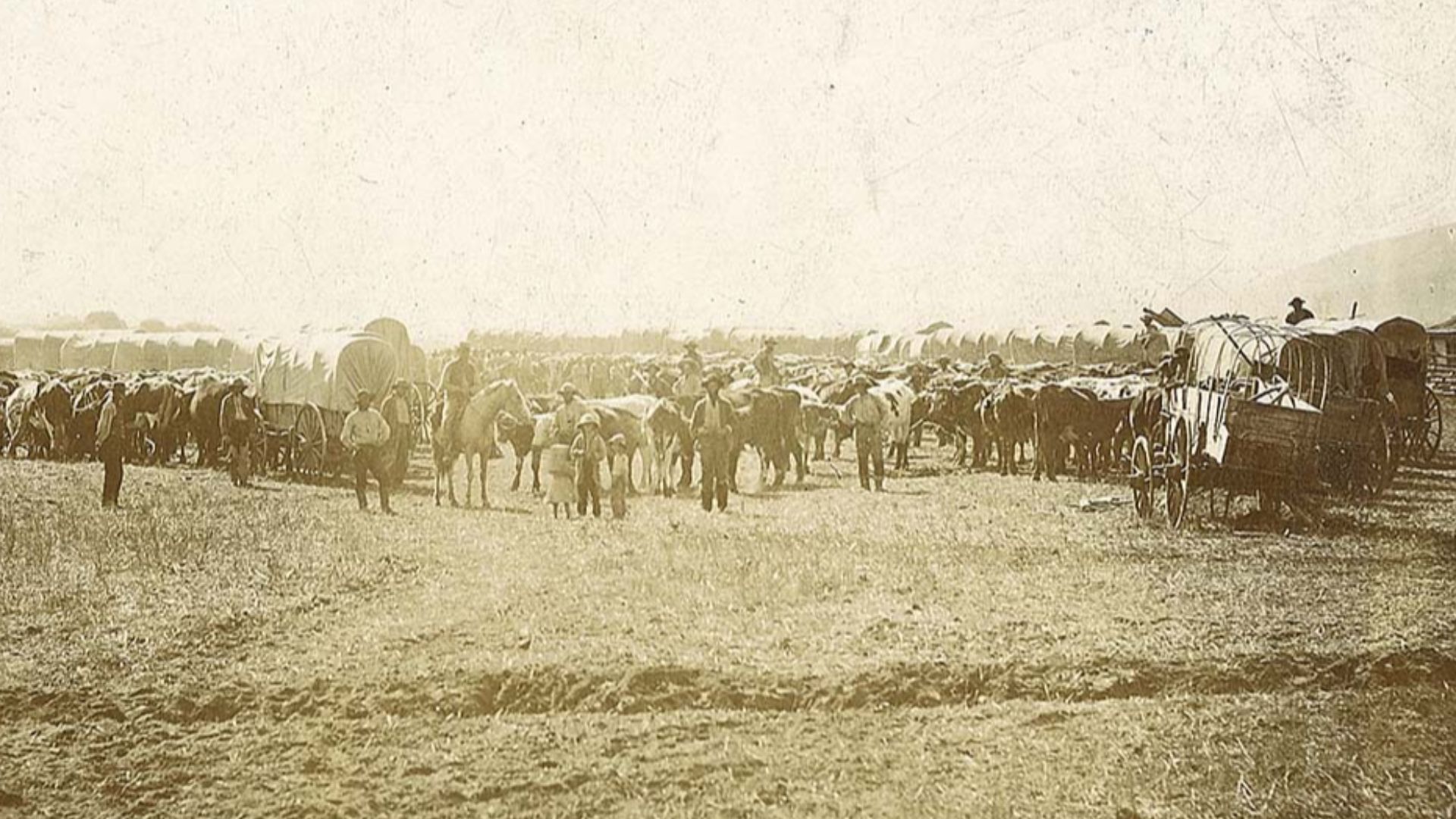

Natural obstacles made things even harder. River crossings and mountain passes could be treacherous—wagons would tip over, animals could drown, and travelers were sometimes swept away by fast-moving water. Still, despite all of these dangers, the journey west attracted nearly half a million people between the 1840s and 1860s.

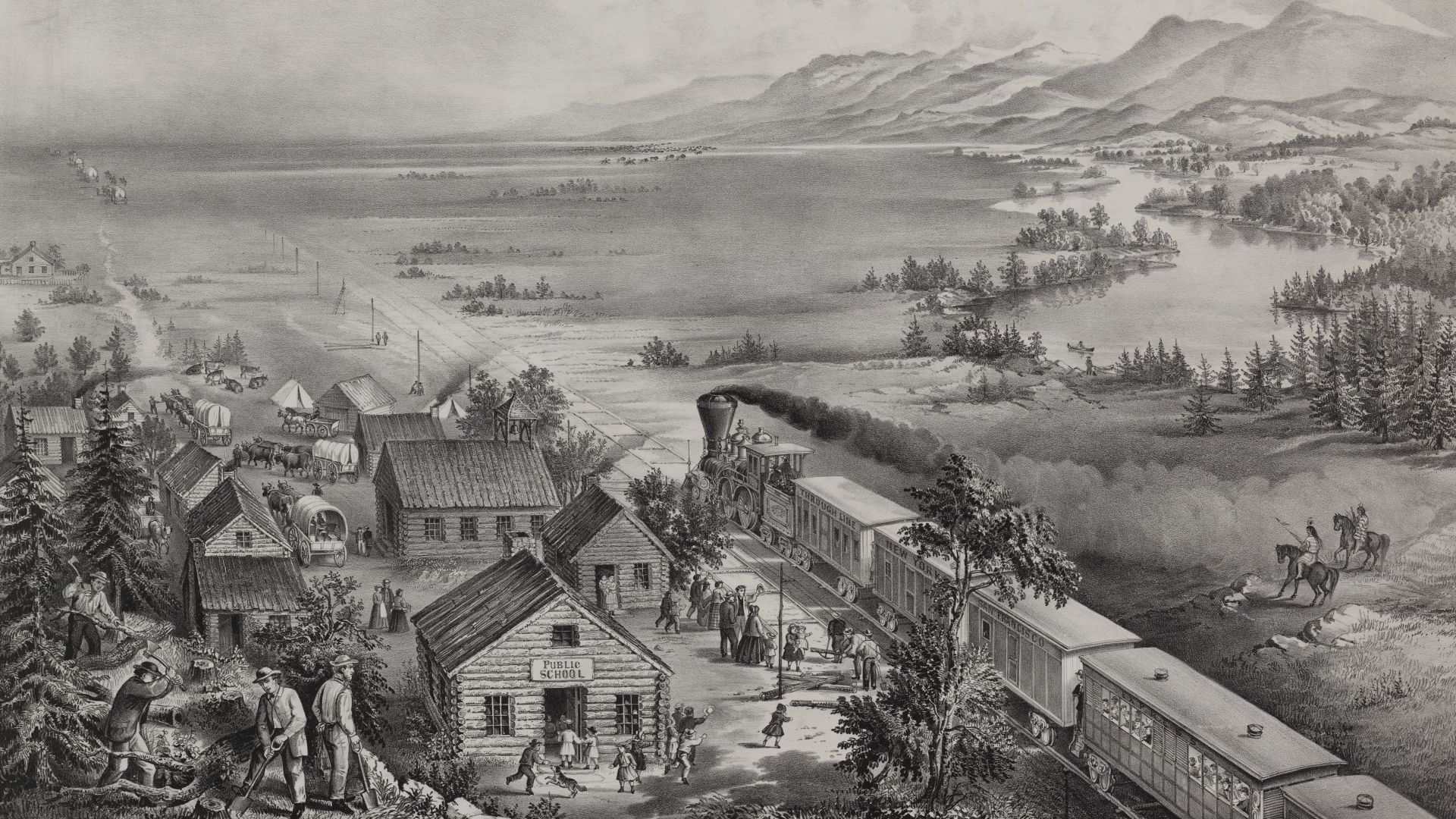

Currier & Ives.; Palmer, F. (Fanny), 1812-1876, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Currier & Ives.; Palmer, F. (Fanny), 1812-1876, artist, Wikimedia Commons

They Risked Everything For Land And Liberty

Through policies like the Preemption Act of 1841 and, later, the Homestead Act of 1862, the US government offered settlers up to 160 acres of public land, provided they made improvements to it. For many, land ownership represented not just economic stability but also personal independence.

Manifest Destiny And The Belief In An Inevitable Mission

This movement was also deeply shaped by the phrase “Manifest Destiny,” coined by John L. O’Sullivan. It was the widespread belief that Americans were destined, perhaps even divinely chosen, to expand across the continent. So, the act of heading west was seen as a vital contribution to a national ideology.

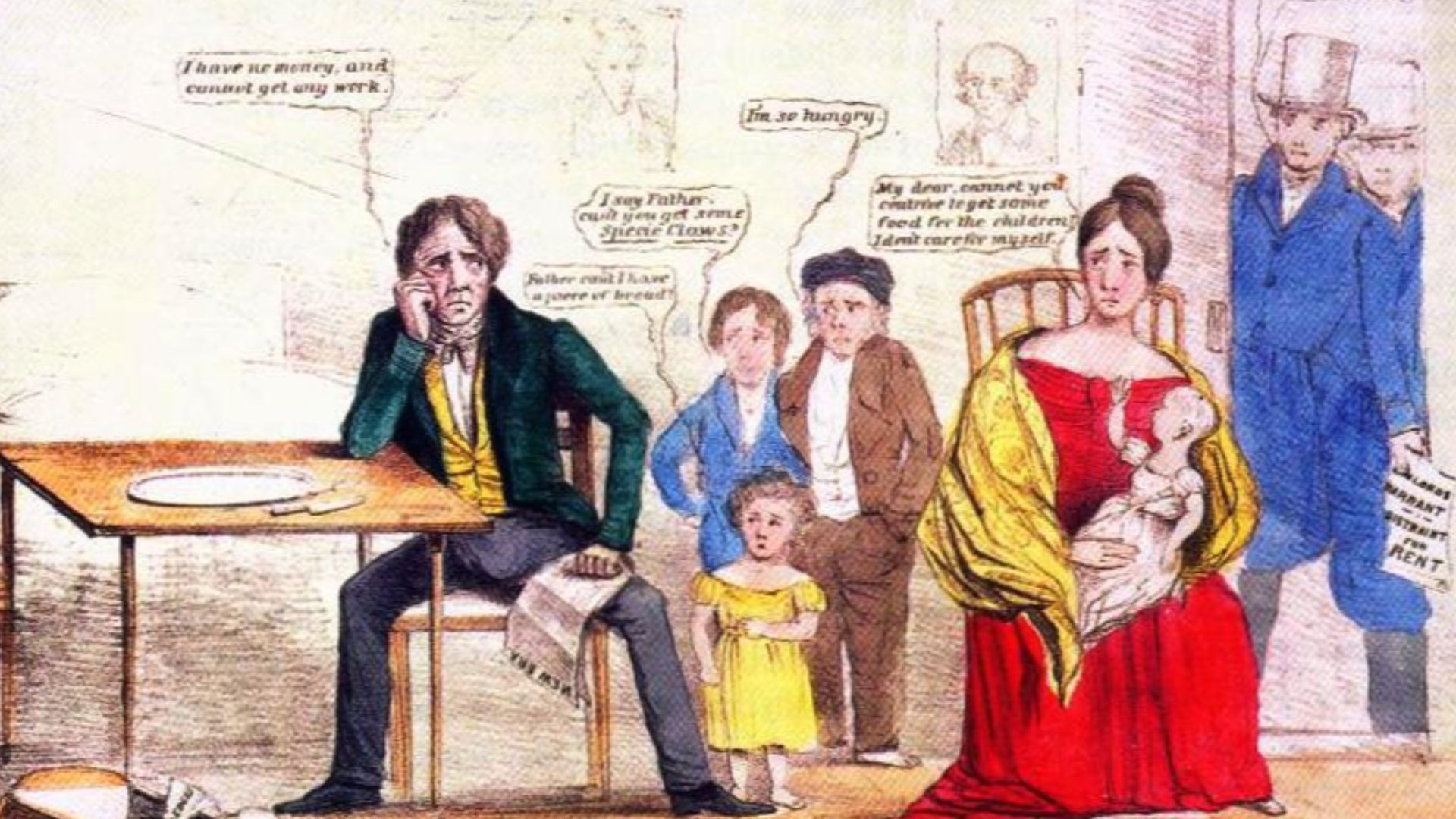

Hard Times In The East Pushed Families Westward

At the same time, financial crises like the Panic of 1837 left large numbers of Americans bankrupt or out of work, with little hope of recovery in the overcrowded cities of the East. The West offered not just land but opportunity, fewer institutional barriers, and eventually, even gold.

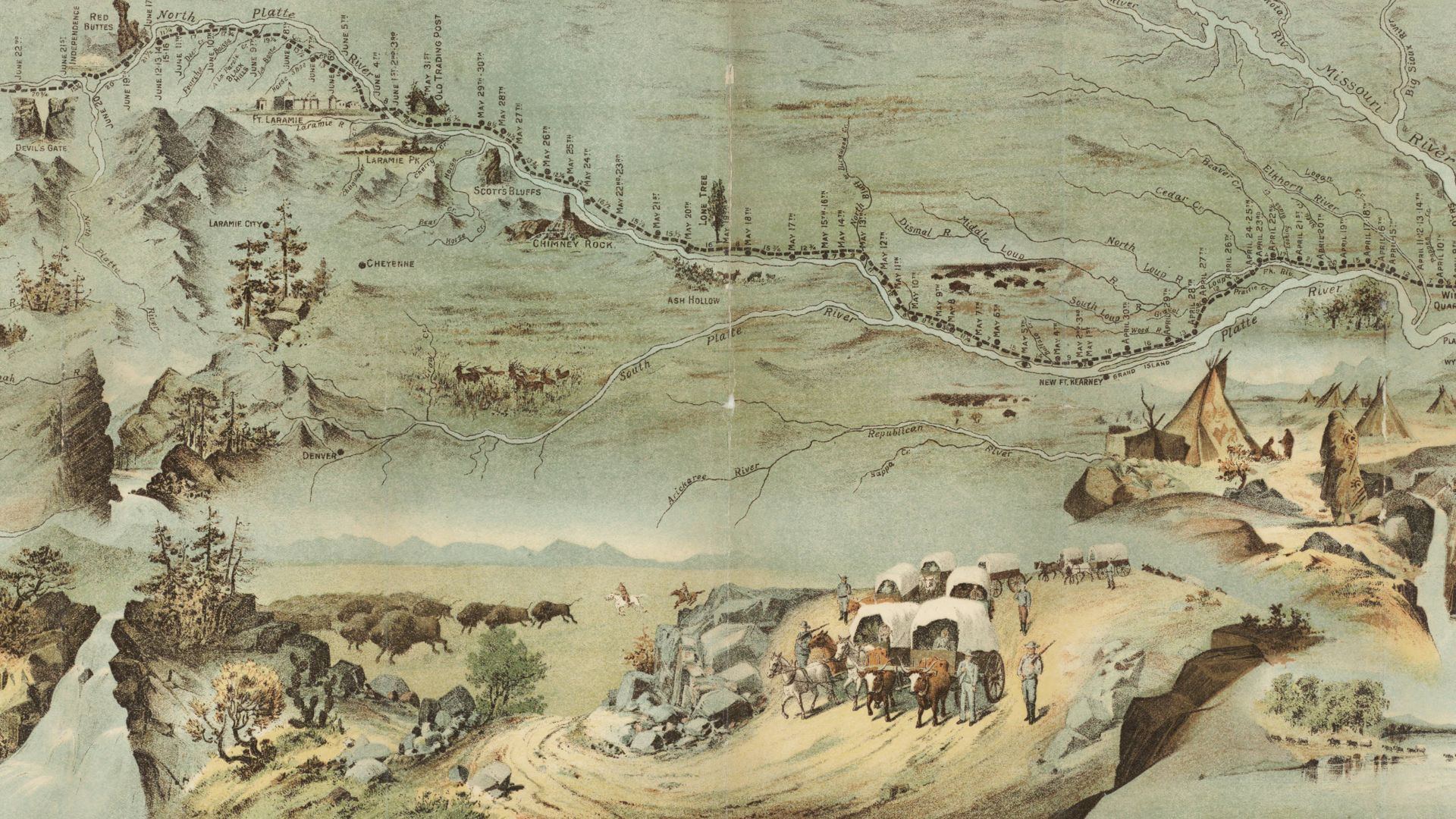

The Oregon Trail That Carried Dreams To The Pacific

The Oregon Trail served as one of the most important routes, spanning approximately 2,170 miles from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon City. One of the most significant moments came in 1843 during the “Great Migration,” when around 700–1,000 settlers made the journey together in one of the earliest organized wagon trains.

Glenn Scofield Williams, Wikimedia Commons

Glenn Scofield Williams, Wikimedia Commons

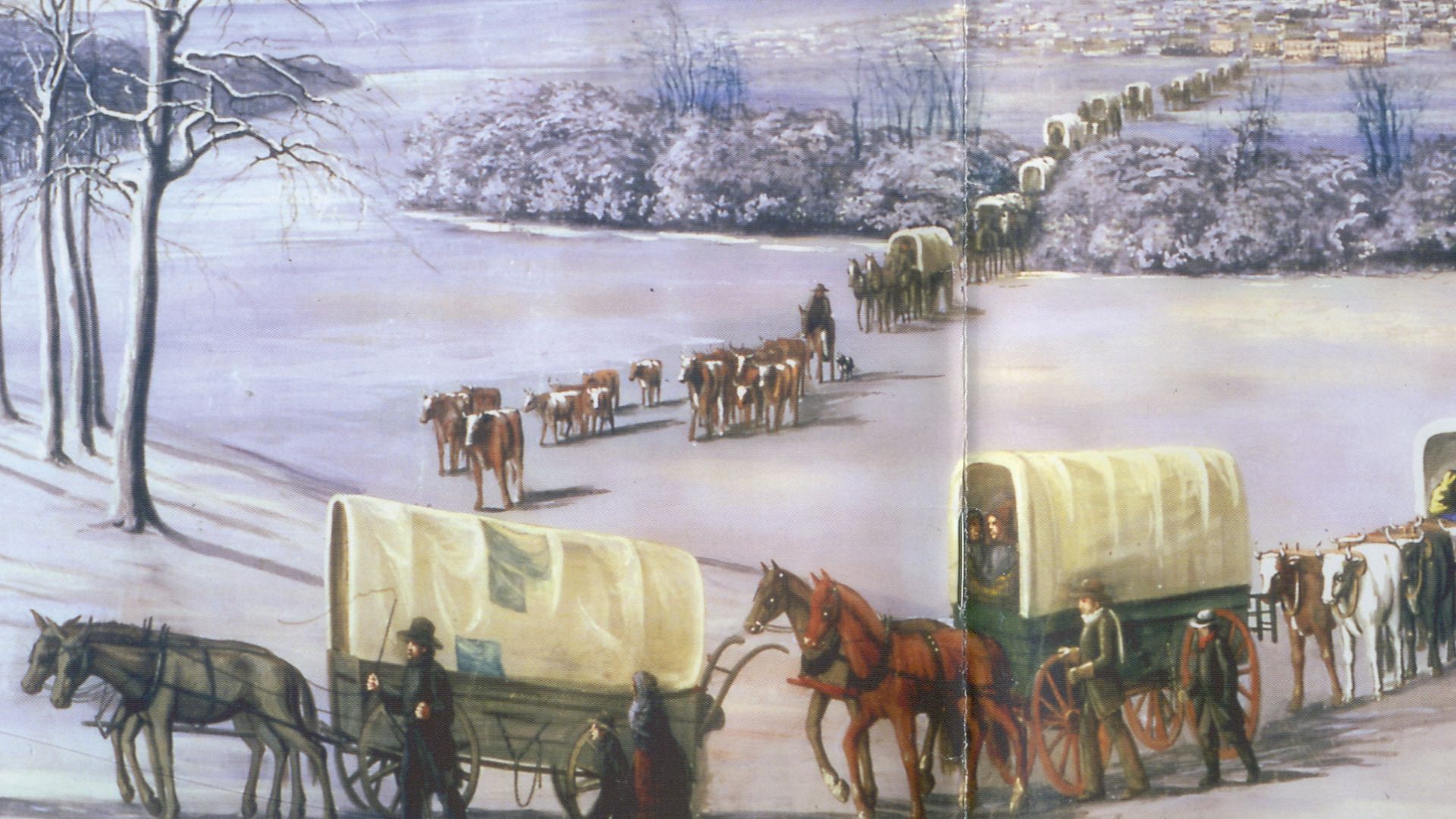

The Mormon Trail Where Faith Led The Way

For the Latter-day Saints, migration was driven primarily by faith. The Mormon Trail was used by members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints seeking religious freedom and refuge from persecution. Some of these groups were formed by poorer migrants who could not afford wagons and suffered extreme hardships.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Saying Goodbye To The Old Life

Before the journey west even began, many pioneers faced the difficult decision to sell nearly everything they owned. Homes, farms, furniture, and tools were liquidated to fund the expedition—often bringing in just enough to cover the cost of outfitting a wagon train. For many, the emotional toll of leaving everything behind was higher.

Packing The Wagon With Only What Could Fit

With limited space and weight capacity, staples like flour, bacon, beans, coffee, and salt made up the core food supply. Tools such as rifles, ammunition, axes, and shovels were packed alongside spare parts. And then, cooking gear, quilts, and additional clothing had to fit wherever there was room.

Theodore Russel Davis, Wikimedia Commons

Theodore Russel Davis, Wikimedia Commons

Choosing Oxen, Mules, Or Horses To Survive The Trail

Oxen were by far the most common animals that pulled the wagon. Though slower than mules or horses, they were strong, reliable, inexpensive, and could survive on poor-quality grass. Mormon emigrants were even known to use milk cows for draft purposes, with about 20 percent of their teams composed of these dual-purpose animals.

John Steuart Curry, Wikimedia Commons

John Steuart Curry, Wikimedia Commons

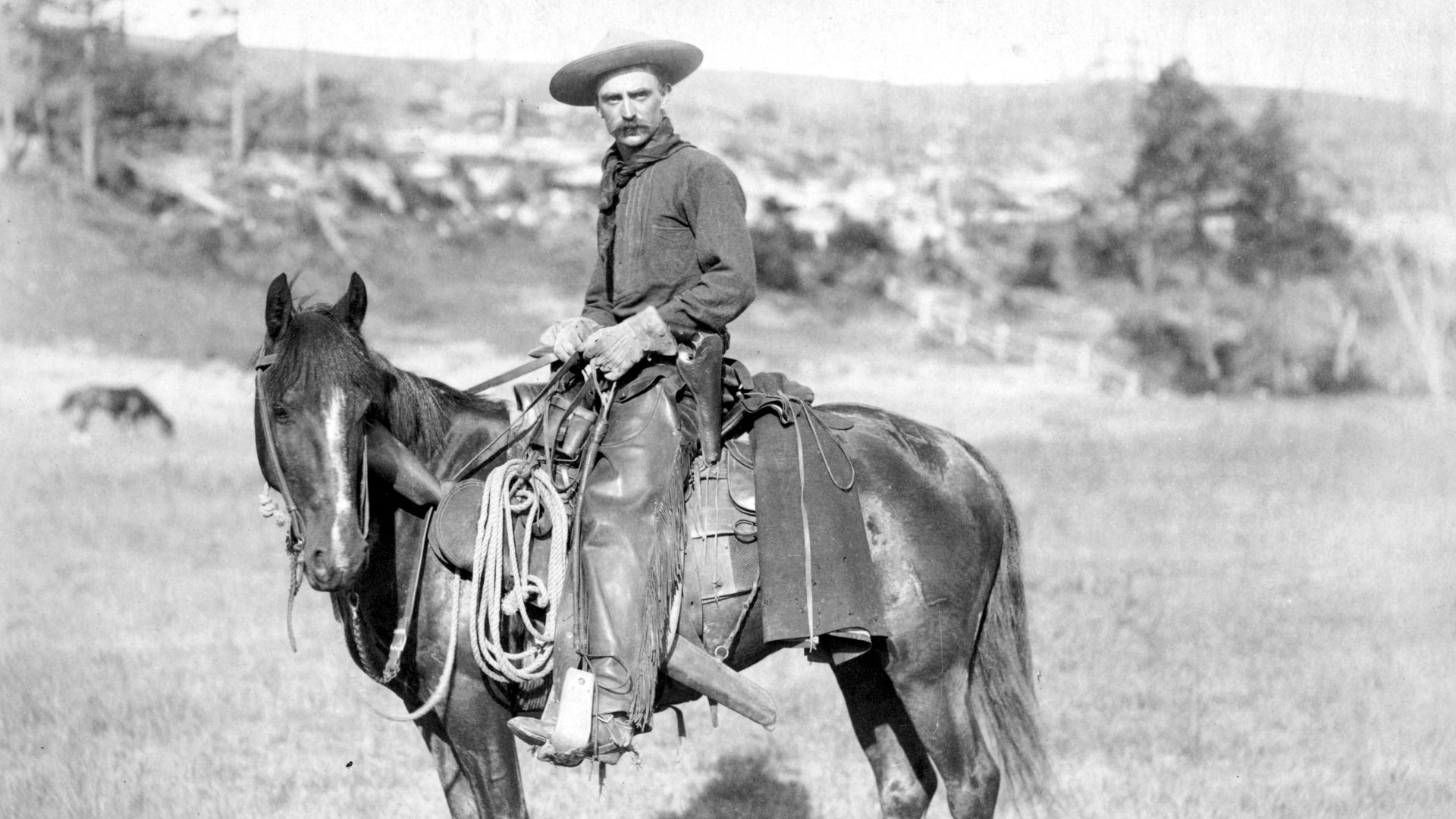

Wagon Masters And Trail Guides Who Kept Order

Trail guides and wagon masters were important, especially in the more treacherous stretches of the journey. They oversaw the group’s daily schedule, handled disputes, made key decisions about travel routes, figured out camp logistics, managed livestock, and whatnot. In dangerous areas, hiring a local guide was pretty common.

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

The First Steps Into The Unknown Were Chaotic

Timing was critical; leaving too early risked muddy trails, while leaving too late meant encountering snow in the Rocky Mountains. The first stretch of travel was mostly disorganized since animals refused to cooperate and wagons frequently broke down. Many settlers struggled to adapt to new routines as well.

Oxley, Walter T., copyright claimant, Wikimedia Commons

Oxley, Walter T., copyright claimant, Wikimedia Commons

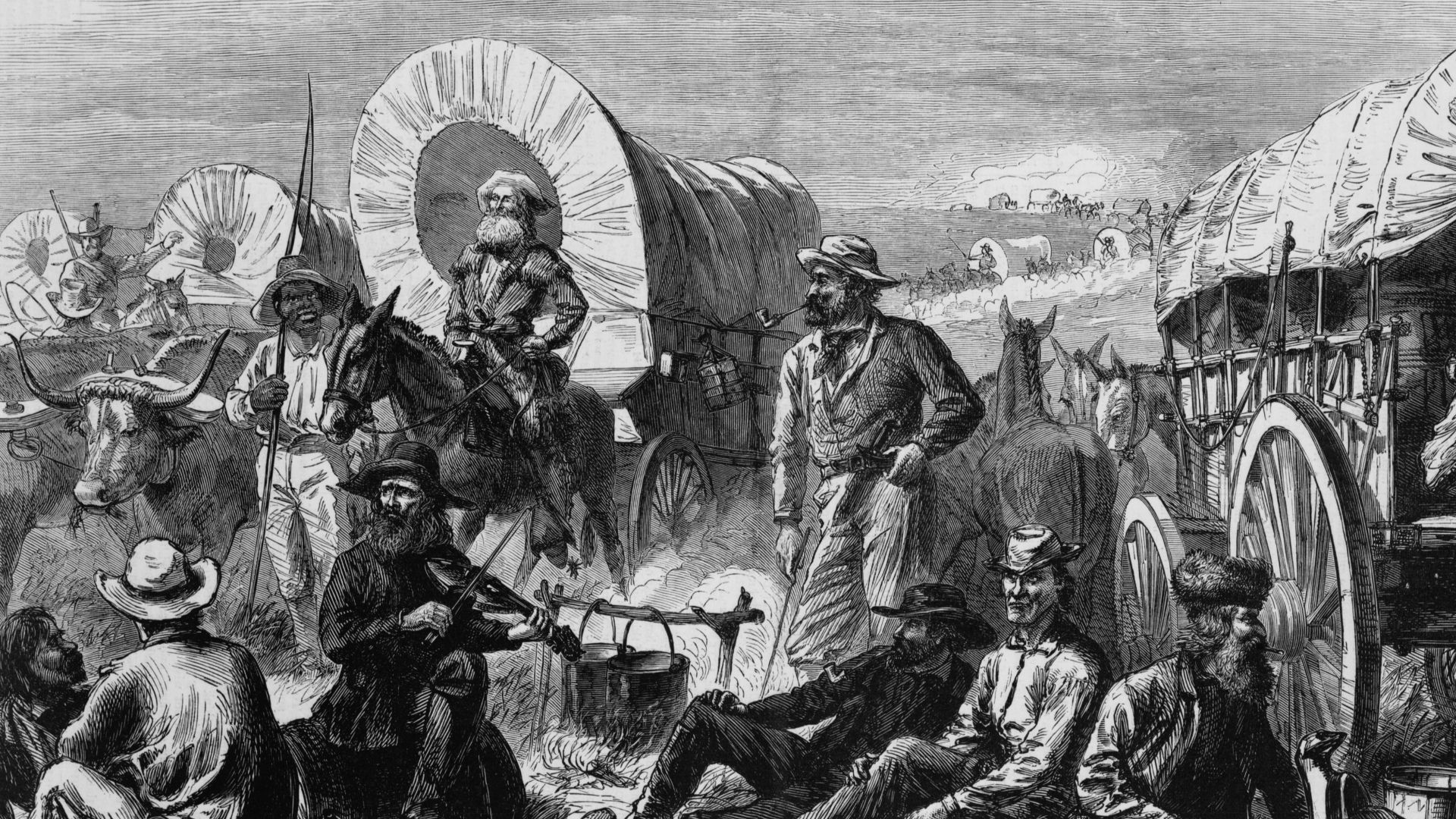

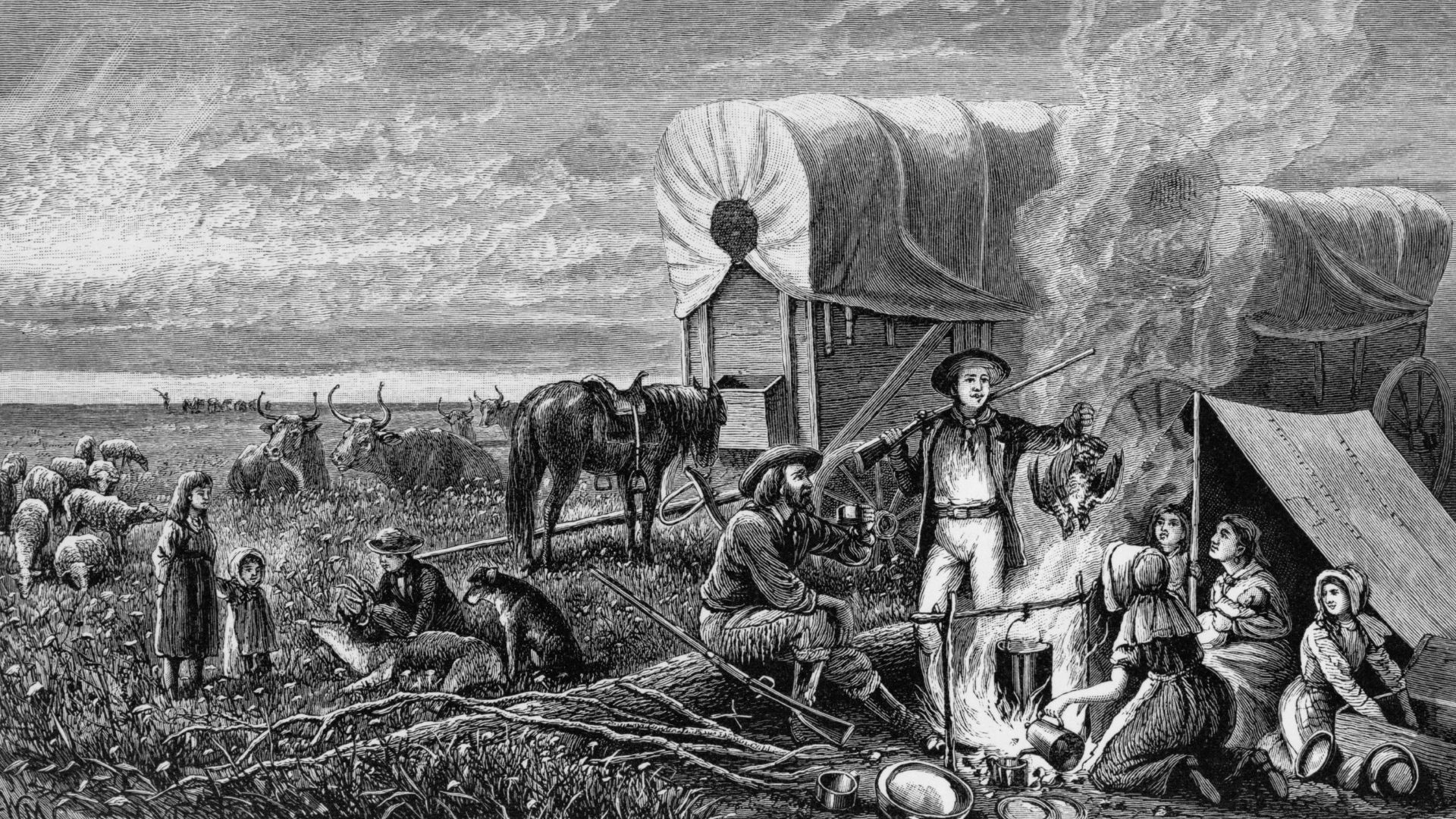

Campfire Camaraderie That Gave Travelers Strength

But despite the challenges, the early weeks were filled with energy. Spirits ran high as families gathered around evening campfires to share meals and swap stories. This early camaraderie gave the journey a communal rhythm. People actually believed they were at the start of something promising—though it wouldn’t always last.

Cary, William de la Montagne, 1840-1922, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Cary, William de la Montagne, 1840-1922, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Walking Beside The Wagon Day After Day

Travelers quickly learned that walking was not optional but routine. With wagons packed full of supplies, most walked 10 to 15 miles a day to conserve space and spare the animals from additional strain. The physical toll became apparent within days.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Children On The Trail Who Learned As They Went

Children, though the most vulnerable on the trail, adapted with surprising speed. Formal schooling was rare, though some parents taught basic reading or math in the evenings. The journey taught them skills like collecting firewood, checking for animals along the way, fetching water, and more.

Emanuel Leutze, Wikimedia Commons

Emanuel Leutze, Wikimedia Commons

River Crossings That Could Claim Wagons And Lives

River crossings were some of the most dangerous and unpredictable moments of the westward journey. Whenever possible, pioneers scouted for shallow, slow-moving stretches to make the crossing less hazardous. In deeper waters, however, some travelers converted their wagons into makeshift rafts, while children and fragile goods were carried across separately to reduce risk.

Henry Bryan Hall, Wikimedia Commons

Henry Bryan Hall, Wikimedia Commons

Mountain Passes Where Wagons Broke And Families Struggled

Mountain passes, like the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada, were also unforgiving, especially later in the season when snow and ice added to the risk. Wagons frequently broke down while climbing over rocky inclines, and repairs had to be made on the trail, either with spare parts or with scavenged materials.

MtDarwinUpload (talk · contribs), Wikimedia Commons

MtDarwinUpload (talk · contribs), Wikimedia Commons

Blizzards, Floods, And Dust Storms That Stalled The Journey

In higher elevations in the Rockies, blizzards could strike with little notice, even in spring and fall. Meanwhile, dry riverbeds, often assumed safe, were vulnerable to sudden flash floods triggered by storms miles away. Since canvas covers offered only basic protection, many pioneers depended on tents or dugout shelters to survive.

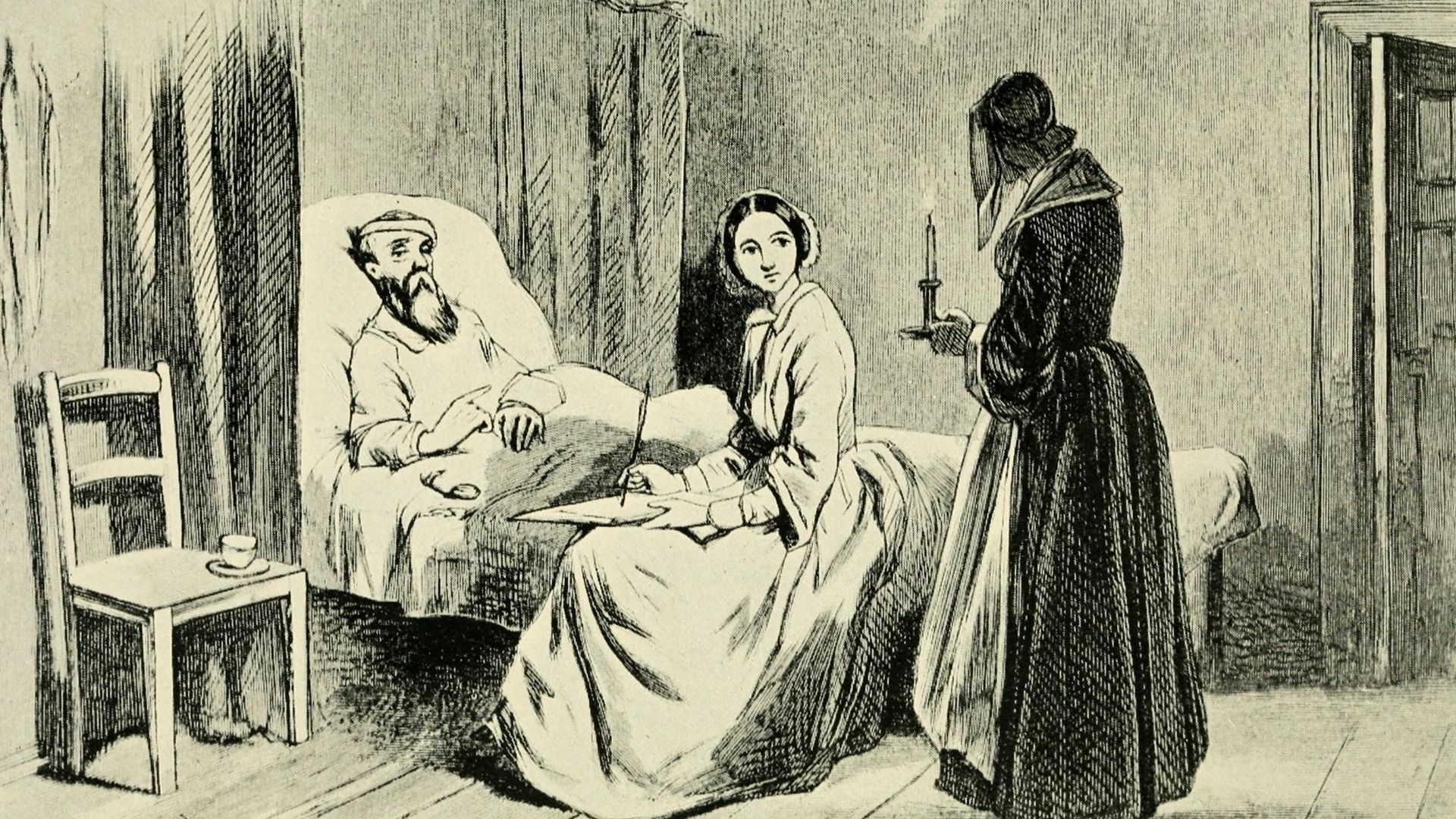

Outbreak Of Cholera And Other Diseases

To make matters worse, cholera outbreaks in the late 1840s and early 1850s claimed thousands of lives. The illness spread quickly in campsites where sanitation was poor and water was drawn from stagnant or contaminated sources. And once cholera appeared, it moved fast through the community.

Pavel Fedotov, Wikimedia Commons

Pavel Fedotov, Wikimedia Commons

Outbreak Of Cholera And Other Diseases (Cont.)

Other illnesses, like dysentery, were widespread and were especially dangerous for children and older adults. Measles also spread easily in the close quarters of a wagon train, posing the greatest threat to those with compromised immunity. The communal nature of travel made isolation and containment nearly impossible.

Gabriele Castagnola, Wikimedia Commons

Gabriele Castagnola, Wikimedia Commons

The Biggest Cause Of These Diseases

Hygiene, already difficult due to water scarcity, became even harder to manage. Bathing was rare, and laundry infrequent. Inside wagons and bedding, travelers contended with bedbugs, lice, and fleas, while rodents would gnaw through food stores, spreading illness in the process.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

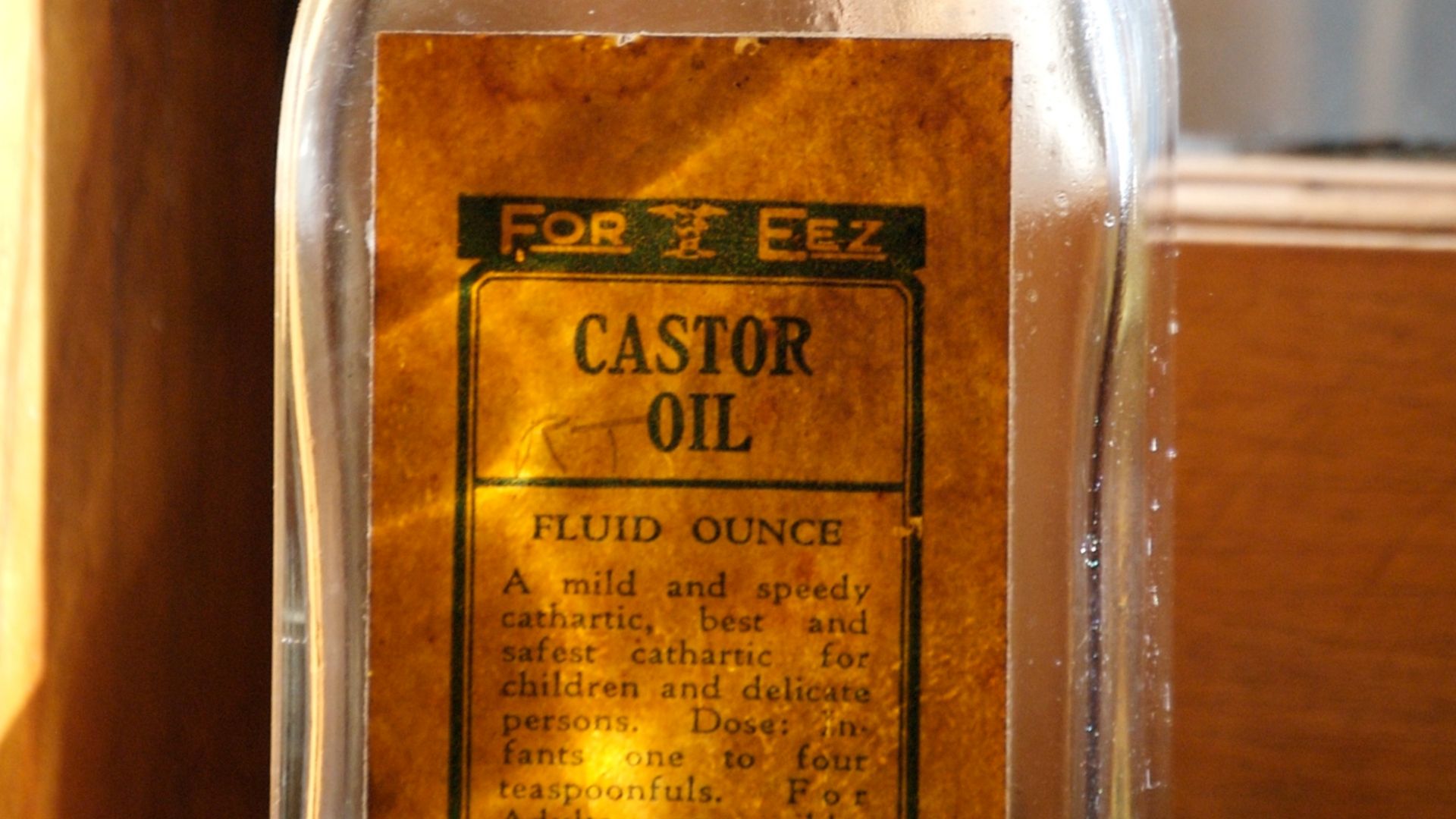

Makeshift Remedies Were Common

Plus, without formal medical care, pioneers relied heavily on folk remedies and whatever supplies they had on hand. Laudanum, an opium-based painkiller, was commonly used, along with camphor for cramps and colds, and castor oil for digestive issues. And if a wagon carried a medical kit, it was usually just basic scalpels, bandages, etc.

Pete Markham from Loretto, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Pete Markham from Loretto, USA, Wikimedia Commons

The Nation’s Longest Graveyard

In such a situation, healing depended on luck, which meant that many migrants did not survive. The emigrant trails came to be known as “the nation’s longest graveyard” because of the ~350,000 who made the journey, up to 30,000 lives were lost and buried in mass graves.

Food That Was Simple But Scarce

Food on the trail was simple and repetitive. Since fresh produce was almost nonexistent, most food had to be preserved using homemade techniques. Cooking was done on heavy cast-iron pots over open flames, but fuel was not always easy to find, so pioneers resorted to burning dried animal dung instead.

Gookins, James F. (James Farrington), 1840-1904, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Gookins, James F. (James Farrington), 1840-1904, artist, Wikimedia Commons

Hunting Game Was Much Needed

As wagon trains moved through areas rich in wildlife, bison, deer, elk, antelope, and smaller game were hunted and preserved, too. In especially lean times, travelers sometimes turned to more desperate measures, eating squirrels, birds, or even boiling leather from harnesses to create something edible.

various gov't employees, Wikimedia Commons

various gov't employees, Wikimedia Commons

Facing Malnutrition On The Trail

This is why malnutrition and vitamin deficiencies were constant concerns. Scurvy, which is caused by a lack of vit C, was particularly common due to the absence of fresh fruits and vegetables. Trail diaries have occasionally described swollen limbs, tooth loss, bleeding gums, joint pain, and other signs of nutritional decline as well.

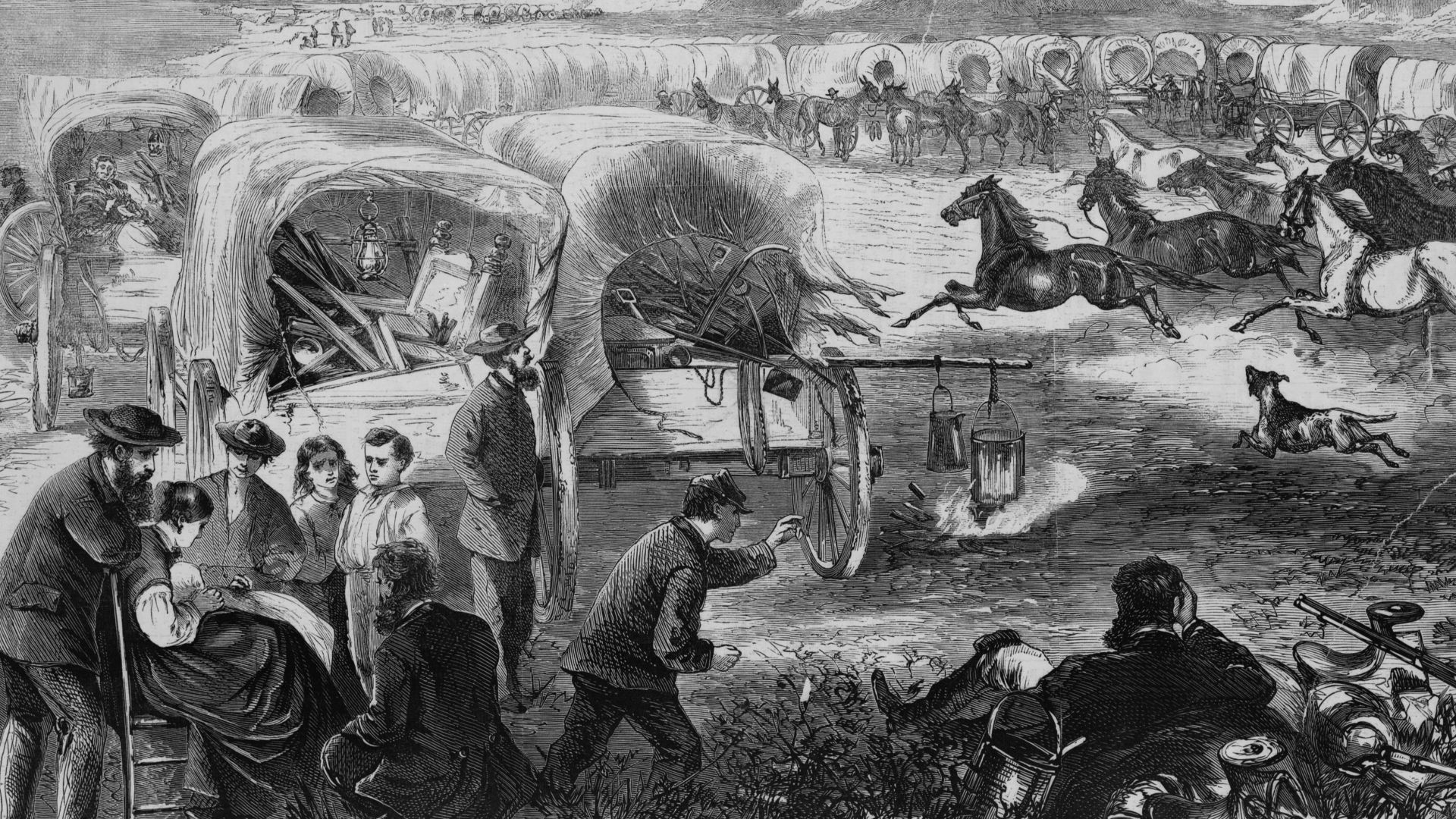

Wildlife And Stampedes That Threatened Livestock And Lives

Wildlife posed real and unpredictable threats along the overland trails. Rattlesnakes were especially common in the Great Plains and desert regions, whose bites, if untreated, could be fatal. So, pioneers carried crude remedies such as whiskey or applied poultices in hopes of slowing the venom, though results were often unreliable.

Wildlife And Stampedes That Threatened Livestock And Lives (Cont.)

Wolves, while less aggressive, were known to scavenge near camps and posed a significant risk to livestock, particularly at night. To guard against such animal intrusion, travelers kept firearms close and posted night watches near the camps.

User:Mas3cf, Wikimedia Commons

User:Mas3cf, Wikimedia Commons

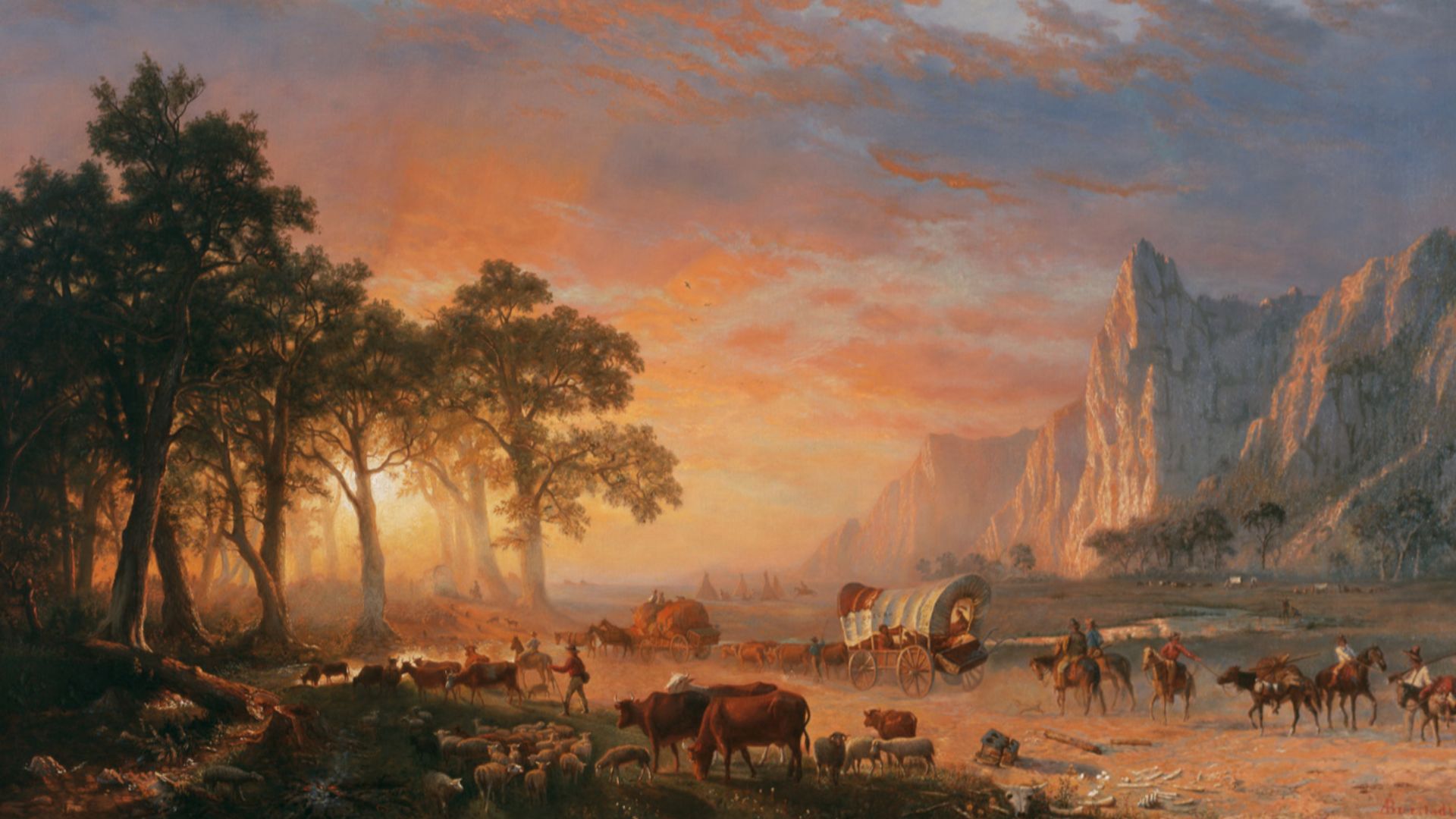

Wildlife And Stampedes That Threatened Livestock And Lives (Cont.)

Livestock, critical to both transportation and survival, brought their own set of concerns. Loud noises like thunder, gunfire, or the sudden presence of predators could send entire teams into a panicked run, leaving wagons immobile. Even without stampedes, livestock faced risks that would make them fall behind the rest of the group.

Albert Bierstadt, Wikimedia Commons

Albert Bierstadt, Wikimedia Commons

Guarding Livestock And Supplies Through The Night

Draft animals were allowed to graze after stopping for the day, but had to be rounded up by dawn. And this task usually fell to guards or older children, who would rise early to gather the animals before the day’s journey resumed.

Guarding Livestock And Supplies Through The Night (Cont.)

Though not as common as illness or equipment failure, robbery and theft were persistent concerns along the trail. With law enforcement largely absent across the frontier, wagon trains were left to settle disputes or punish wrongdoers themselves. Hence, many emigrants carried concealed weapons for protection.

U.S. Forest Service- Pacific Northwest Region, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Forest Service- Pacific Northwest Region, Wikimedia Commons

Bartering Was Common

Trading along the route became an essential strategy for survival for travelers. For this, Fort Laramie and Fort Bridger became central locations where wagon trains could restock vital goods. Bartering would happen amongst fellow travelers, and also Native communities who would offer berries, fish, or game in exchange for metal tools or firearms.

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

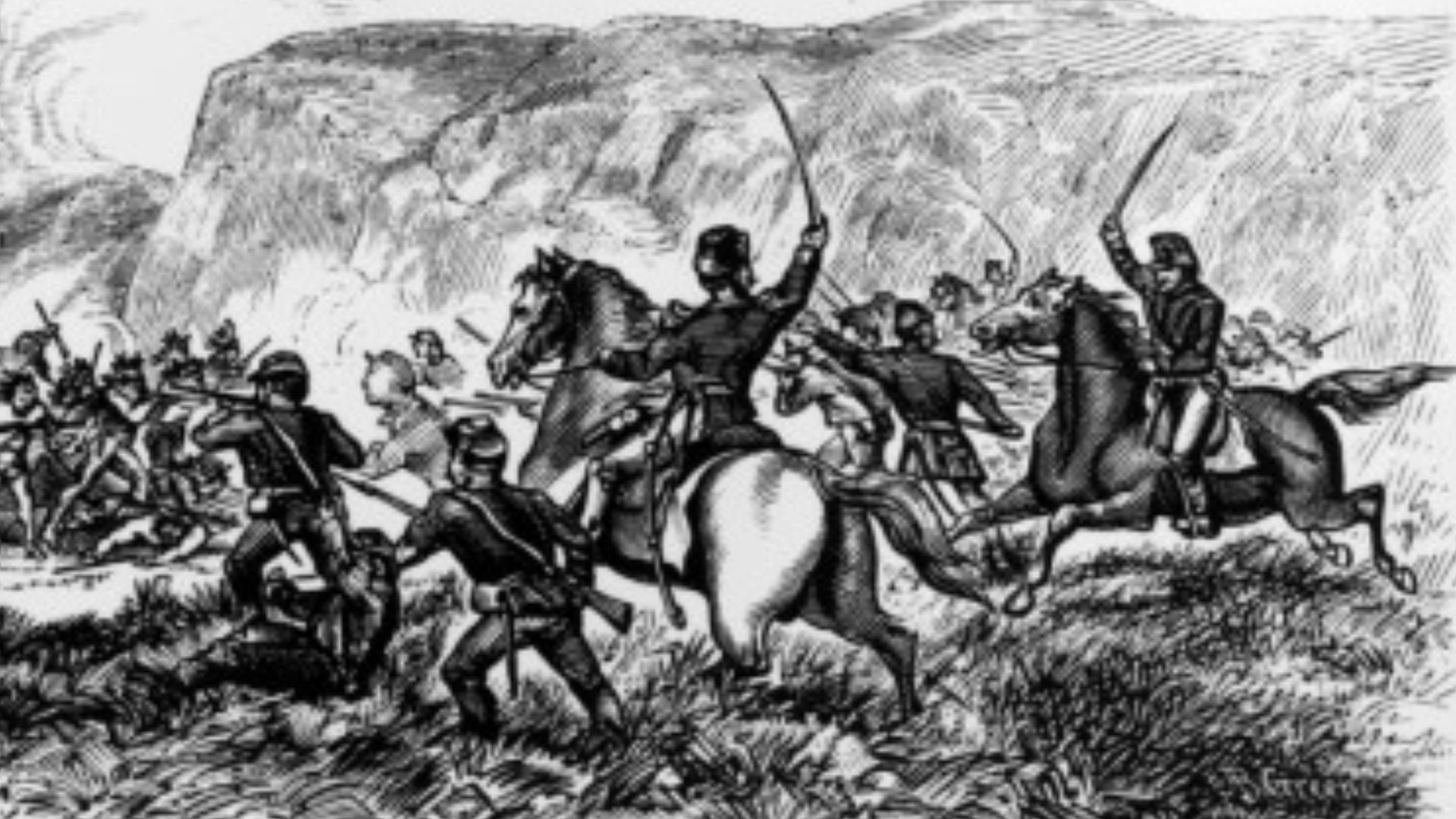

Encounters With Native Communities

Stories of violent encounters with Indigenous peoples have often dominated portrayals of westward migration, but they don’t reflect the full reality. While conflicts did occur, especially in areas strained by encroachment or past military tensions, most interactions were based on trade.

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Jacob Miller, Wikimedia Commons

Encounters With Native Communities (Cont.)

Violence was more likely to arise where land disputes or resource depletion fueled resentment. Notable incidents like the Battle of Ash Hollow in 1855 stand out, but they were exceptions. Many wagon trains passed through tribal lands without incident—particularly when mutual respect and trade were prioritized.

L. U. Reavis, Wikimedia Commons

L. U. Reavis, Wikimedia Commons

Internal Conflict Was Inevitable

Within the wagon trains themselves, internal conflict was almost inevitable. These mobile communities had to make constant decisions. Some groups elected a wagon master, while others operated more democratically. So, moral debates over whether to abandon struggling members could create deep divisions. There were times when individuals were asked to leave the group entirely.

W. H. Jackson. Copied by H.H.Ritter march 1938., Wikimedia Commons

W. H. Jackson. Copied by H.H.Ritter march 1938., Wikimedia Commons

The Role Women Played

Women played an indispensable role in life on the trail, though their contributions have often been overlooked in broader historical accounts. They managed daily survival tasks—cooking, tending to children, nursing the sick, and maintaining morale—all while enduring the same physical toll as the men.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Role Women Played (Cont.)

Then, in moments of crisis, they took on even more. They drove wagons and fiercely defended the camp when it was needed. Widowhood was tragically common, and women who lost husbands were forced to lead their families alone, but with the support of the community.

Published in above-mentioned work, which was by Benjamin F. Gue, Wikimedia Commons

Published in above-mentioned work, which was by Benjamin F. Gue, Wikimedia Commons

The Role Women Played (Cont.)

The Covered Wagon Women series, edited by Kenneth L. Holmes, brings together the writings of over 100 women who traveled west between 1840 and 1890. These entries capture everything from the routines of cooking over buffalo chips and delivering children on the move, to the heartbreak of burying family members and enduring harsh weather.

Millroy & Hayes , Wikimedia Commons

Millroy & Hayes , Wikimedia Commons

Campfire Stories And Shared Fears That Built Community

Evening campfires served as the emotional center of trail life. After supper, families would gather to share stories, sing songs, and reflect on the day’s progress. Conversation around the fire often turned to the practical and the ominous: upcoming terrain challenges, past mishaps, or rumors of danger ahead.

Charles Roscoe Savage, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Roscoe Savage, Wikimedia Commons

Sleeping Under The Stars Or Beneath The Wagon

When it came time to sleep, most travelers bedded down on the ground beneath the open sky, using little more than quilts or any other fabric for warmth. Some chose to sleep under the wagons for shelter from wind or rain, while others used tents—if they had the space and resources to carry one.

Adrien Marie, Wikimedia Commons

Adrien Marie, Wikimedia Commons

Dreams Of Arrival And Nightmares Of Loss

Despite the hardships, the dream of reaching their destination became their driving force. Letters and diary entries often express a powerful mix of hope and fear. Many envisioned a fresh start—a land of their own, with thriving farms. They simply hoped for stability.

Arrival Brought Relief And Regret

Arriving in Oregon, California, or Utah marked the conclusion of a grueling journey, but it did not always signal the start of a better life. People were exhausted and malnourished, bearing the weight of grief from family members or animals lost along the way.

Settling New Towns And Building Futures Across The West

Still, many families pressed forward with building new lives. Across the West, pioneers founded hundreds of new towns. For the families who survived, the migration left a permanent mark. And while some families rose to prominence, becoming part of the larger mythos of the American frontier, others faded into obscurity.

John C. H. Grabill, Wikimedia Commons

John C. H. Grabill, Wikimedia Commons