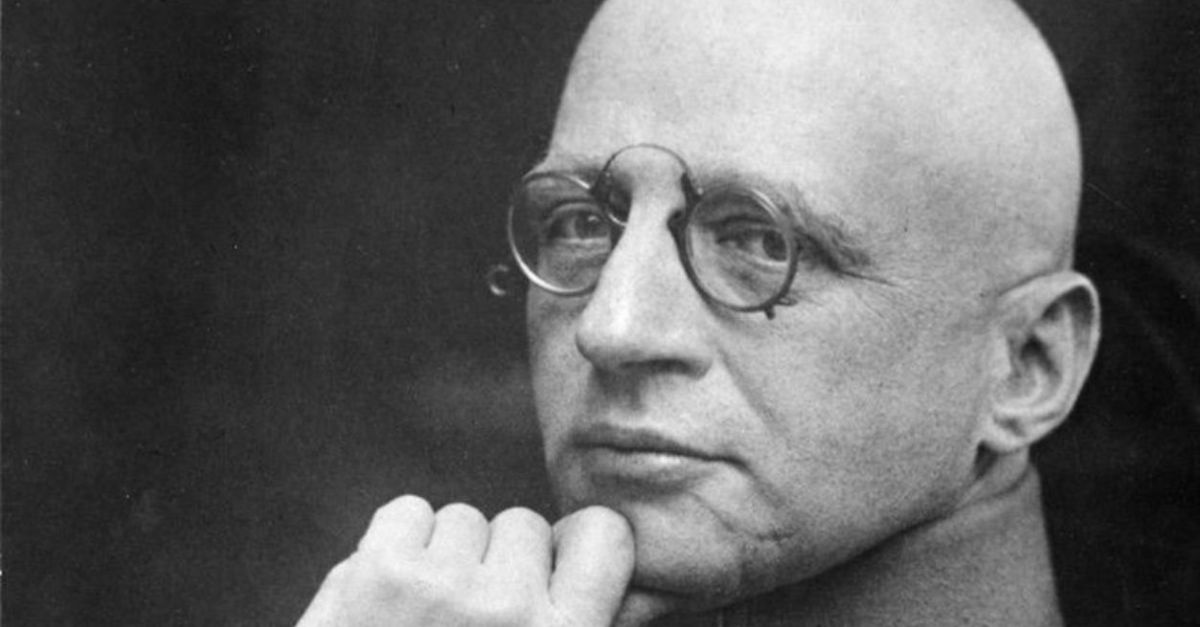

Both A Savior And A Destroyer

Few people have shaped the modern world like Fritz Haber. He helped end famine and sparked a revolution in farming. But the same man also turned chemistry into a weapon of destruction. His story is both brilliant—and deeply unsettling.

A Boy Born Into A World On The Brink

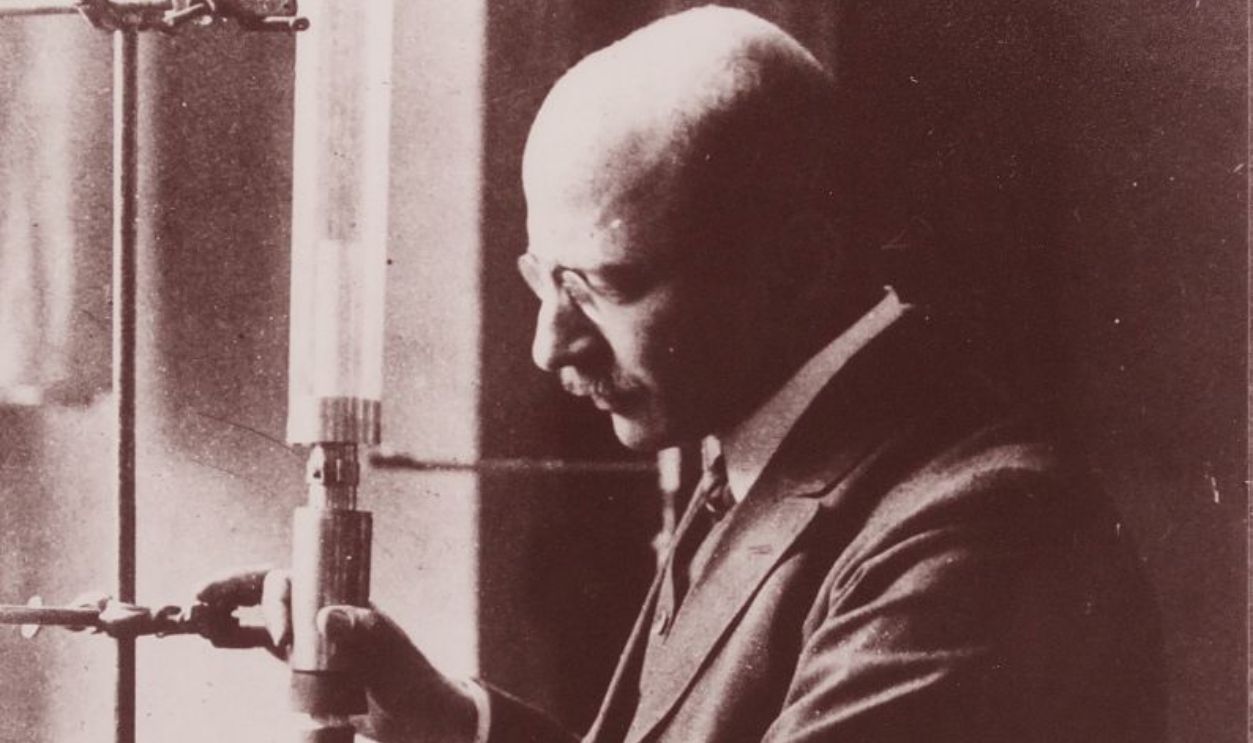

Fritz Haber entered the world in 1868, in Breslau, a city buzzing with trade and industry in the German Empire. Raised in a wealthy Jewish family, he grew up watching a country obsessed with progress and scientific ambition.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Curiosity Lit A Fire In His Mind

As a child, Fritz Haber showed a strong interest in how things worked. He was especially fascinated by science and technology, often spending time reading about chemistry. This early passion for understanding the physical world would quietly shape the path he chose later.

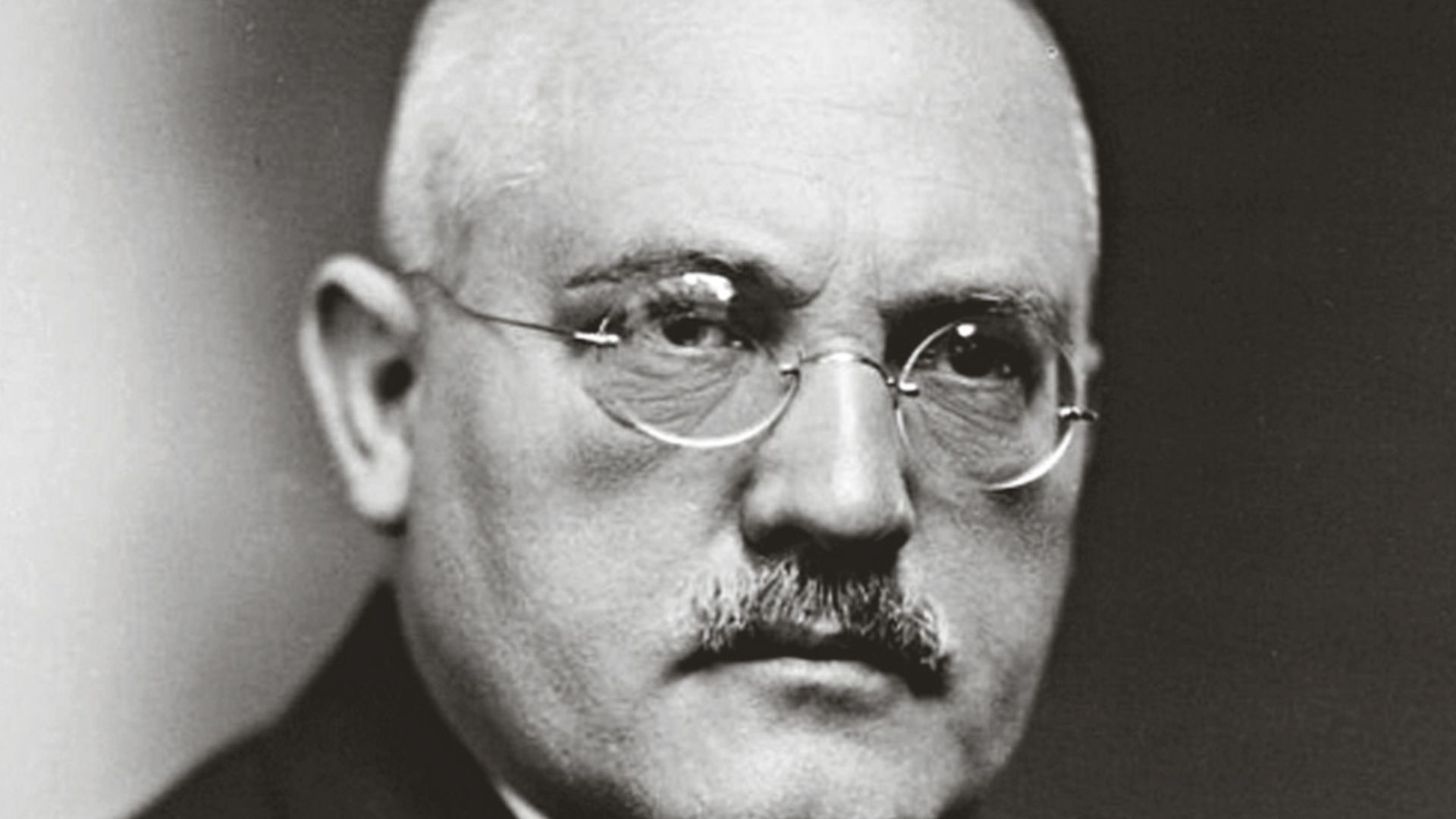

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

From Lecture Halls To Laboratories

As he moved through Germany’s top universities, Haber soaked up knowledge from the best minds in chemistry. He earned his doctorate in 1891, but he had little interest in theory alone. For him, science had to be useful, or it wasn’t enough.

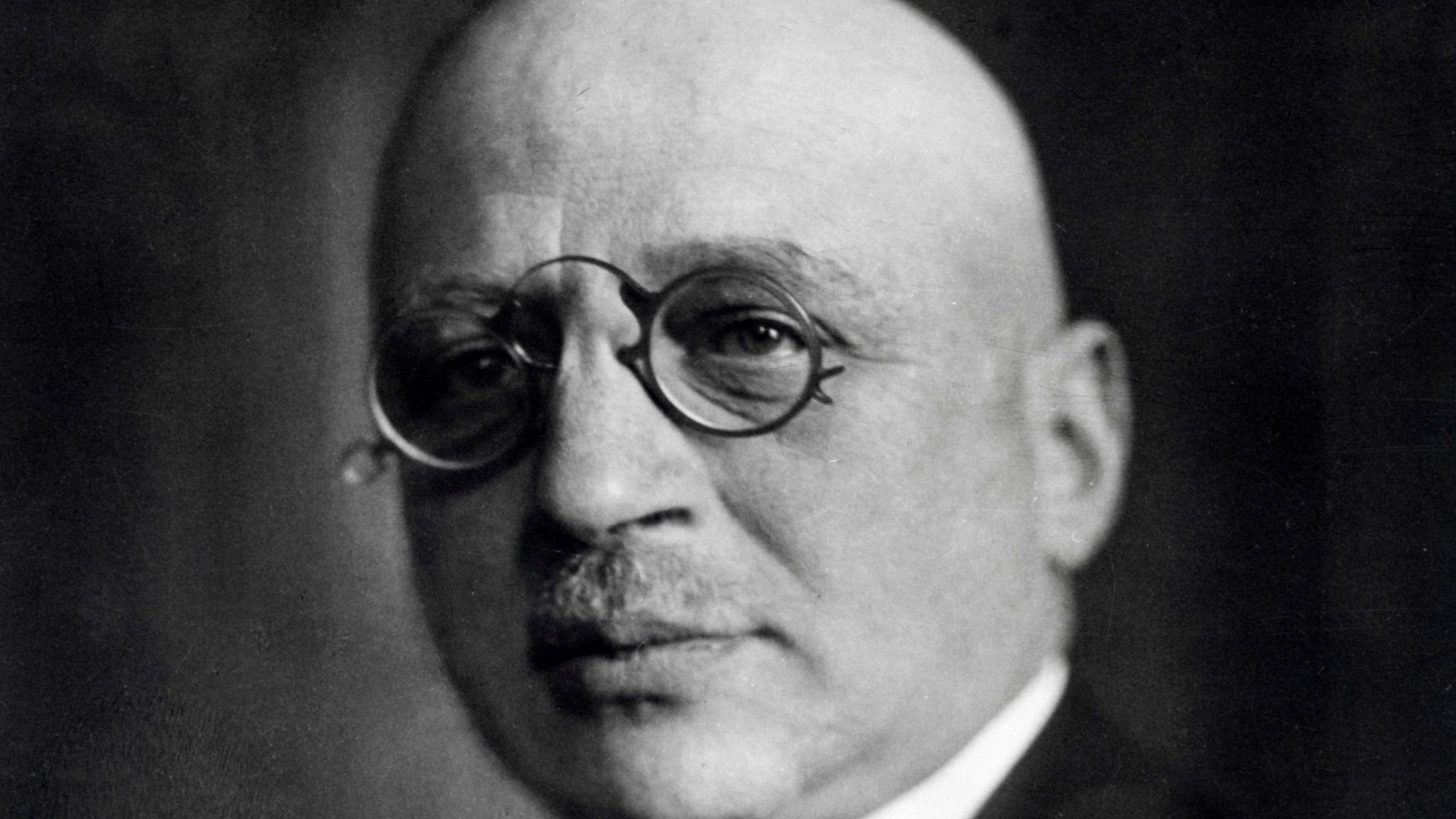

UnknownUnknown , Wikimedia Commons

UnknownUnknown , Wikimedia Commons

Climbing The Ranks In A Nation That Loved Science

After earning his doctorate, Haber took a teaching role at the Technical College of Karlsruhe. Germany at the time treated scientists like national heroes. His sharp thinking and tireless work quickly earned him respect among students and government officials alike.

The Growing Problem Beneath The Soil

As Haber’s career took off, the world’s farmland faced a silent threat. Crops needed nitrogen to grow, but the supply in the soil kept running out. Natural sources like manure or bird droppings weren’t enough. Without more nitrogen, food production would collapse.

The Nobel Foundation, Wikimedia Commons

The Nobel Foundation, Wikimedia Commons

Searching For A Way To Feed The Earth

Scientists knew Earth’s atmosphere was full of nitrogen, but it was locked in a form plants couldn’t use. The challenge was turning air into something solid (ammonia) that could fertilize crops. Many had tried and failed. Haber decided he would find a way.

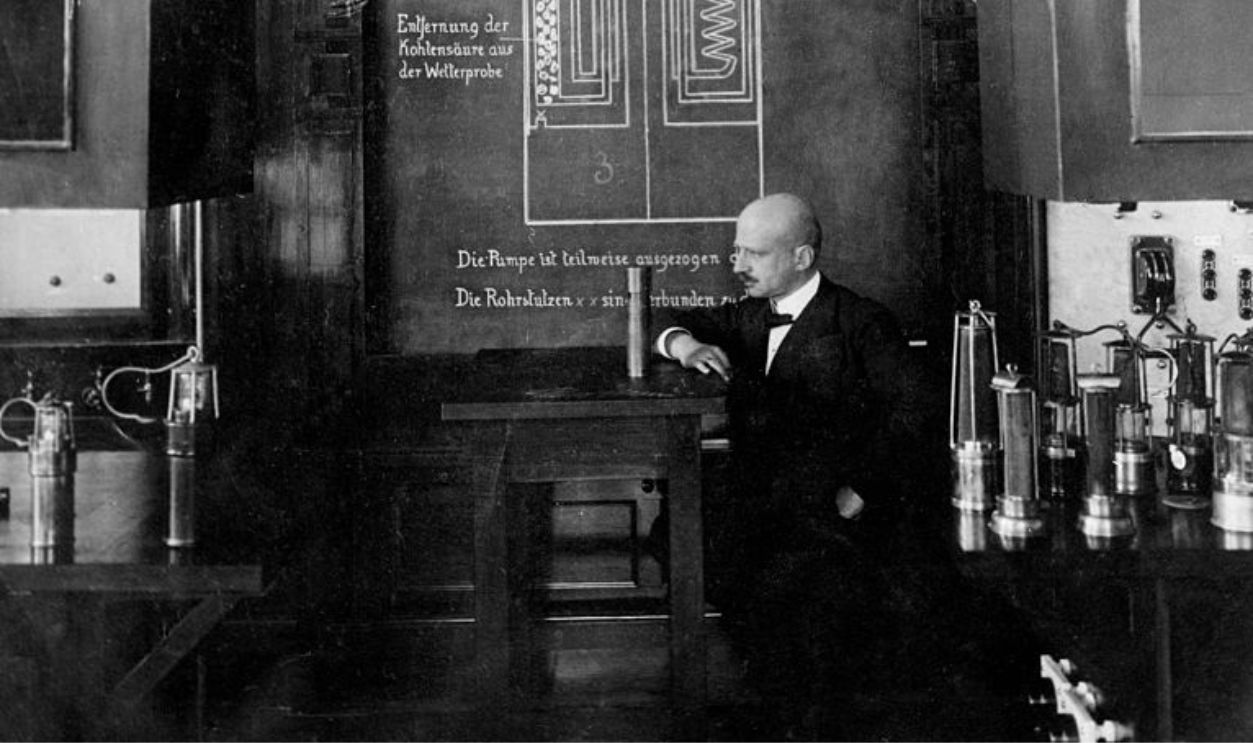

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Breaking The Barrier With Fire And Steel

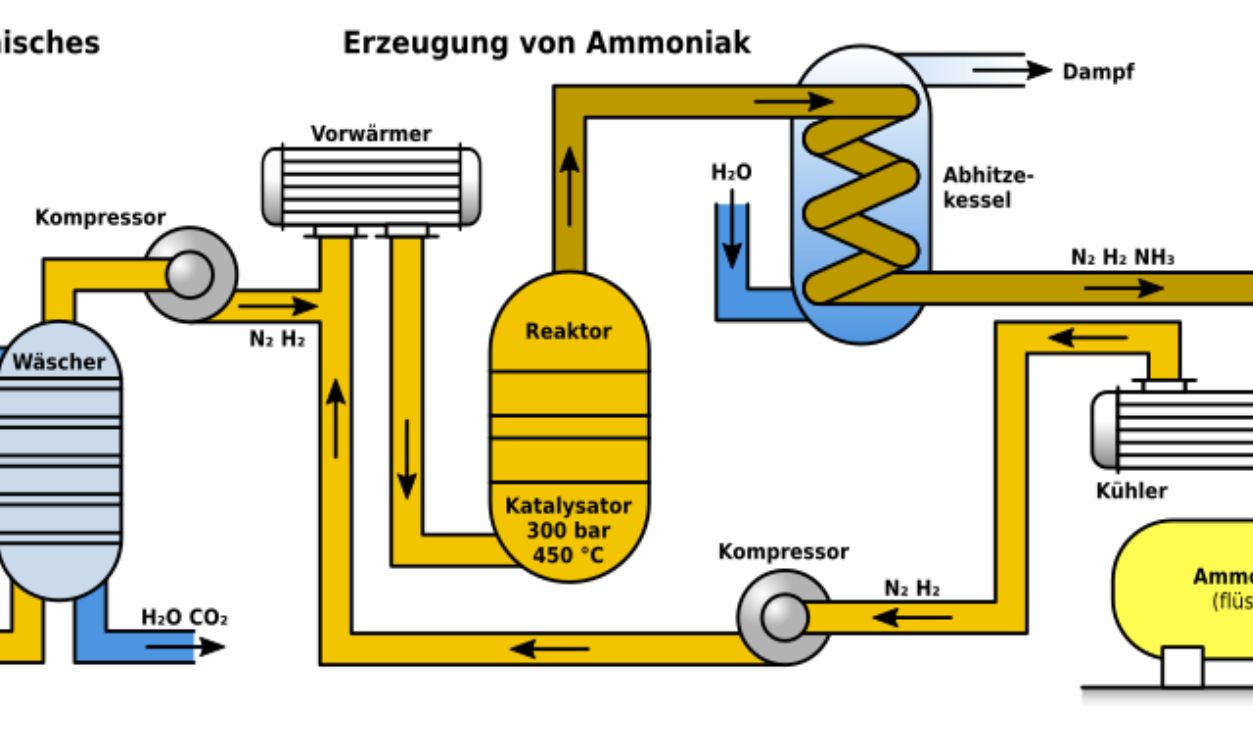

In 1909, after years of trial and error, Haber succeeded. By forcing nitrogen and hydrogen together under intense heat and pressure, he created ammonia. It was a lab-sized miracle—liquid fertilizer pulled from thin air. No one had done it before.

From Breakthrough To Global Game Changer

Haber’s invention was just the beginning. To feed the world, it had to work on an industrial scale. German engineer Carl Bosch stepped in, building machines that could handle the pressure. Together, they turned a tabletop reaction into a global revolution.

BASF Corporate History, Wikimedia Commons

BASF Corporate History, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

The Process That Fed Billions

The Haber-Bosch process changed everything. For the first time, fertilizer could be made in massive amounts, without needing natural deposits. Farmers across the world began producing more food than ever before. What had once been a famine crisis began to fade.

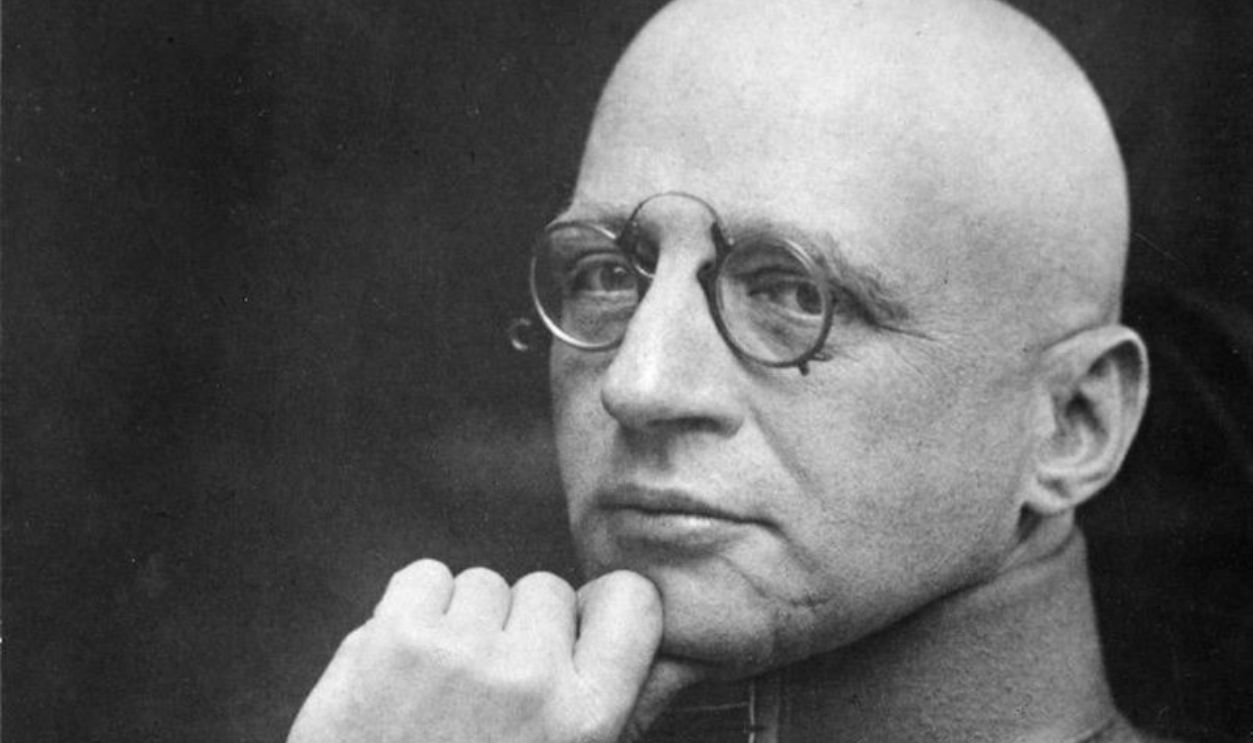

Winning Praise And A Place In History

In 1918, Fritz Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. The world praised him for helping prevent starvation on a global scale. His method would eventually support the diets of nearly half the planet’s population—a staggering scientific legacy.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A World Marching Toward War

But as Haber’s fame grew, Europe was falling apart. By 1914, WWI had begun. Nations turned their industries into war machines, and science was pulled into battle. And Haber, a proud German patriot, believed his skills belonged on the front lines.

Fred C. Palmer (died 1936-1939), Wikimedia Commons

Fred C. Palmer (died 1936-1939), Wikimedia Commons

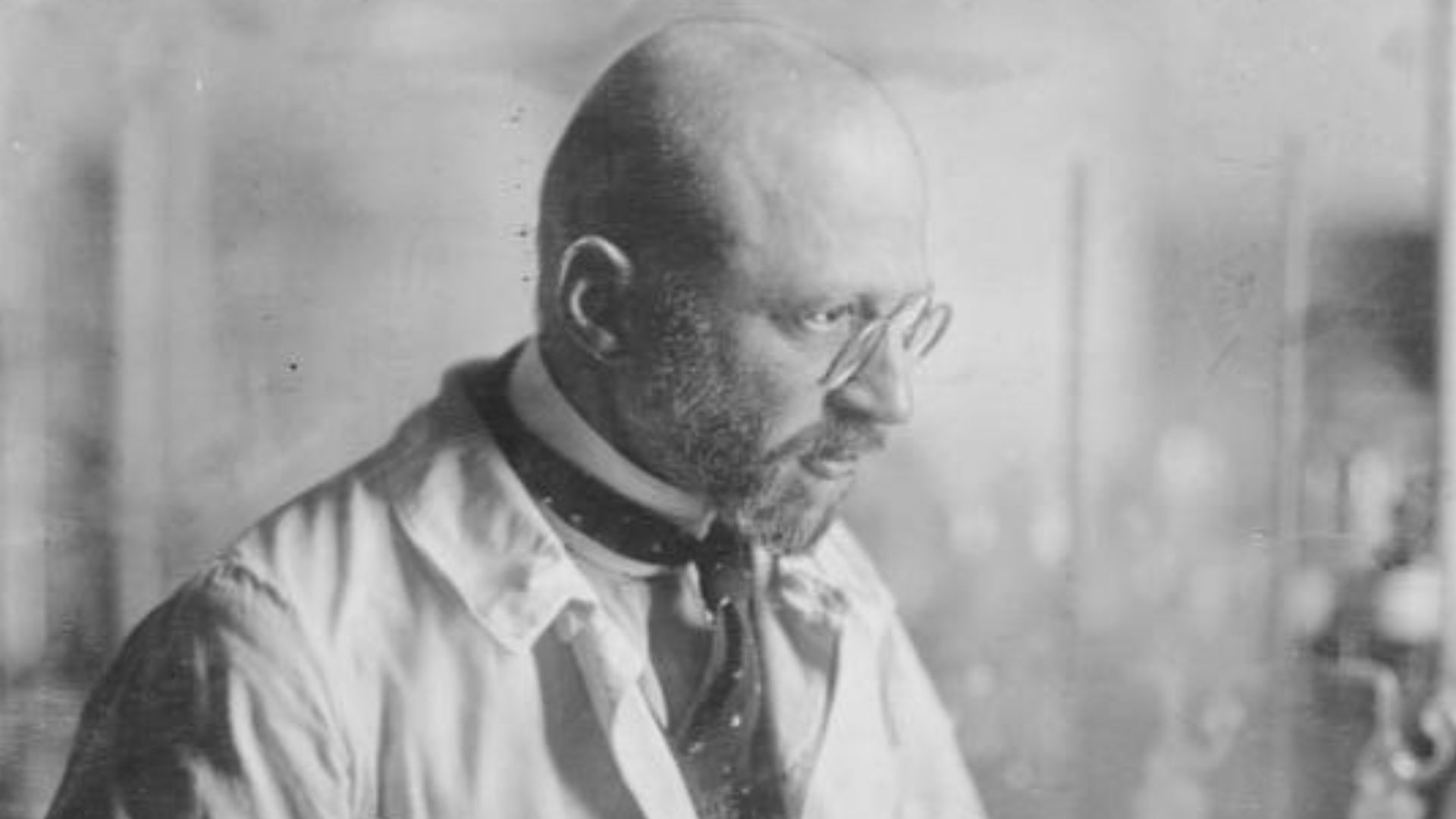

Turning Chemistry Into A Weapon

Haber offered his expertise to the German army, not to make guns, but gas. He helped develop chlorine gas, a deadly weapon that drifted silently across trenches. For him, this wasn't a betrayal of science. It was just another kind of problem to solve.

Bibliotheque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons

Bibliotheque nationale de France, Wikimedia Commons

The First Deadly Cloud Over Ypres

In April 1915, the Germans released chlorine gas on Allied troops near Ypres, Belgium. The greenish-yellow cloud blinded, choked, and killed. Thousands died in minutes. Haber was there, watching. The attack shocked the world, as modern warfare had entered a new and terrifying chapter.

He Saw Victory Where Others Saw Horror

To Haber, the gas attack was a success. It broke the stalemate and showed the power of science in conflict. While others recoiled, he believed chemical weapons were more humane than bullets—quick and efficient. His logic stunned even fellow scientists.

Thomas Keith Aitken (Second Lieutenant), Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Keith Aitken (Second Lieutenant), Wikimedia Commons

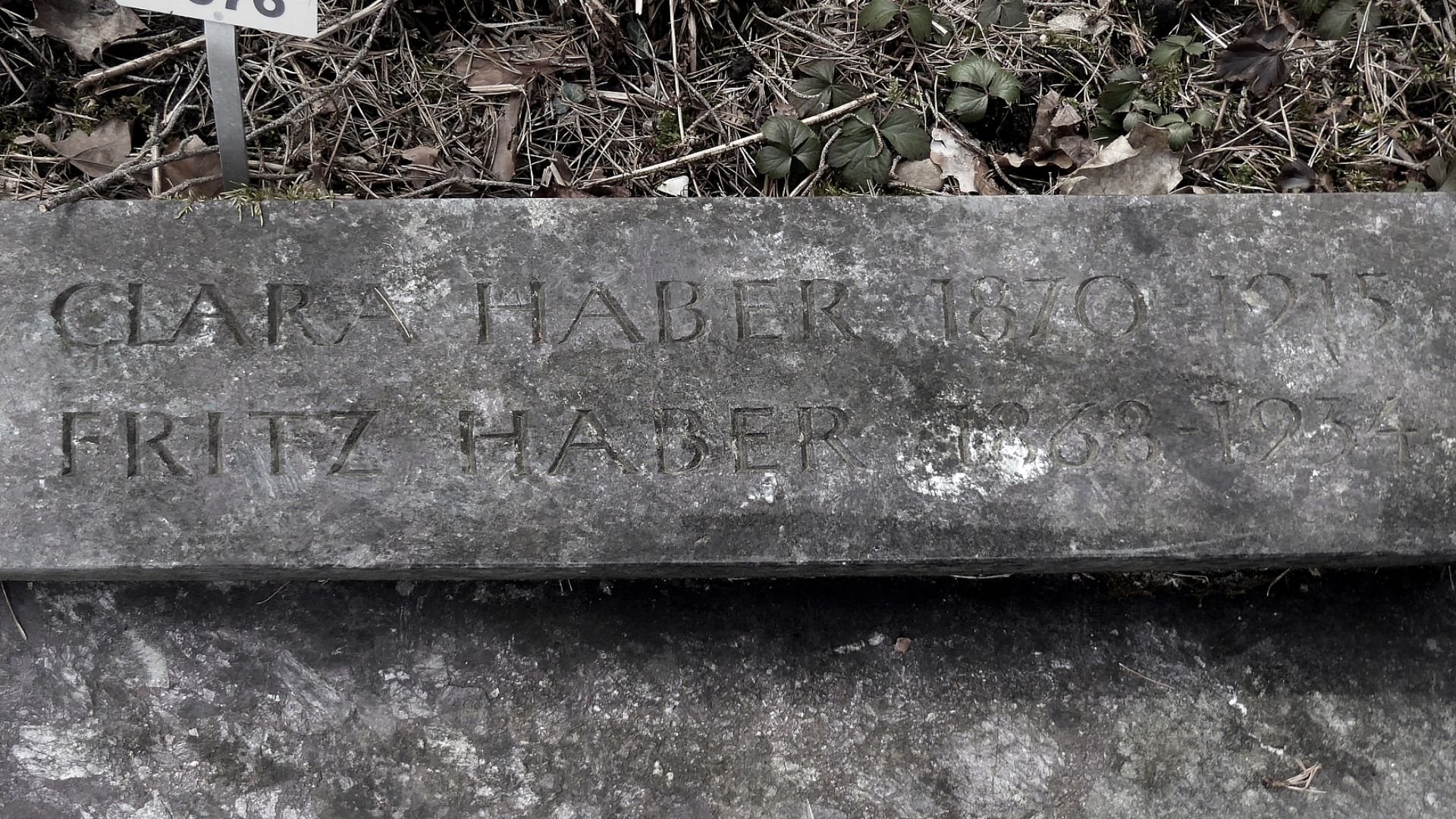

Clara Haber And A Tragedy At Home

Clara Immerwahr, Fritz Haber’s wife, was a pioneering chemist who believed science should never be used to harm. After he oversaw the first gas attack, she withdrew in despair. A few days later, she took her own life. However, Haber returned to the battlefield the next morning.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Fertilizer And Explosives From The Same Discovery

The ammonia Haber helped create wasn’t just for crops—it also made explosives. During the war, Germany relied on it when they lost access to natural nitrate mines. His invention fed people, but it also kept artillery shells flying for years.

BASF Corporate History, Wikimedia Commons

BASF Corporate History, Wikimedia Commons

The World Took Notice—And Took Sides

While some saw Haber as a patriot, others called him a criminal. Chemical weapons had killed tens of thousands. His Nobel Prize then became controversial. Could a man who invented poison gas still be honored for saving lives?

Mondadori Portfolio, Getty Images

Mondadori Portfolio, Getty Images

Trying To Rebuild In A Shaken World

After WW1, Germany was battered—politically, economically, and morally. Haber returned to science, hoping to shift focus back to peaceful research. He led the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin by working on everything from pesticides to gold extraction from seawater.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Science Was Still His Shield

Despite criticism, Haber believed he had done his duty as a scientist and as a German. He refused to see a divide between his wartime work and his Nobel-winning discovery. To him, both served the nation, and both served progress.

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

A Chemist Without A Country

As the 1930s approached, Germany was changing fast. The rise of the Nazi Party brought strict racial laws. Though Haber had converted to Christianity, his Jewish ancestry made him a target. The country he had served so loyally now turned against him.

Topical Press Agency, Getty Images

Topical Press Agency, Getty Images

Exile And A Divided Legacy

In 1933, Fritz Haber resigned from his institute after being forced out under Nazi racial laws. He sought refuge abroad but never found true belonging. He died the following year in Switzerland, leaving behind a legacy both celebrated and condemned in equal measure.

brandstaetter images, Getty Images

brandstaetter images, Getty Images

A Process That Still Feeds The Planet

Today, the Haber-Bosch process is used around the world. It produces over 150 million tons of ammonia each year. Nearly half of all food grown globally depends on it. Without it, billions of people simply wouldn’t be alive today.

Sven, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sven, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Birth Of Modern Chemical Warfare

Haber didn’t invent poison gas, but he made it practical on a large scale. His methods inspired decades of research into chemical weapons. What began in WWI echoed through later conflicts—proof that some scientific doors, once opened, never close again.

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

ullstein bild Dtl., Getty Images

What Progress Really Costs

Fritz Haber left behind a world he helped feed and a world he helped wound. His story shows that science doesn’t stand apart from its consequences. What we create can save or destroy—and progress always demands a choice we can’t undo.