A Legacy That Won’t Be Forgotten

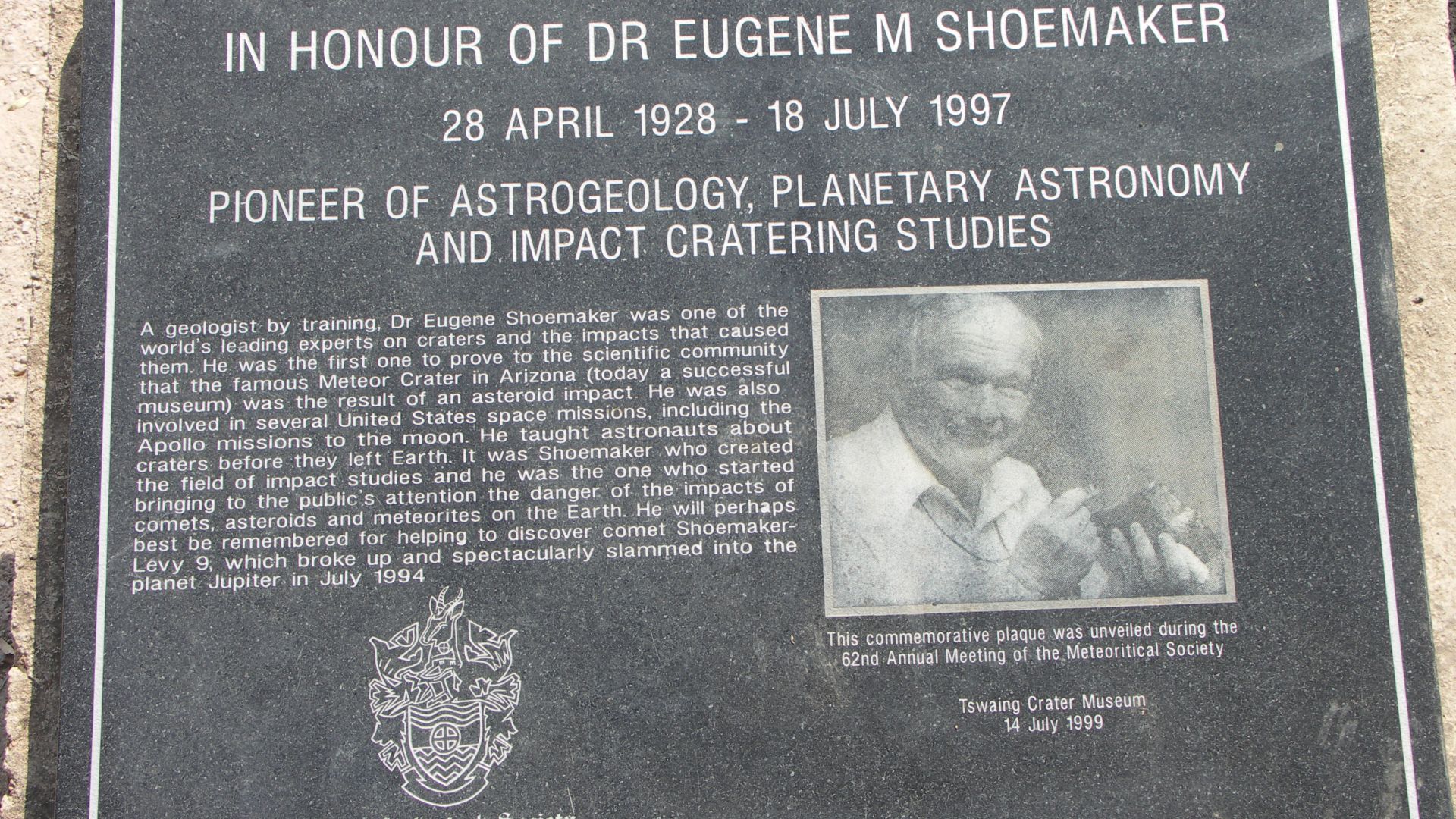

Dreams of walking on the Moon slipped away when Eugene Shoemaker’s health grounded him. But his story didn’t end there. NASA honored his life’s work by giving him something extraordinary.

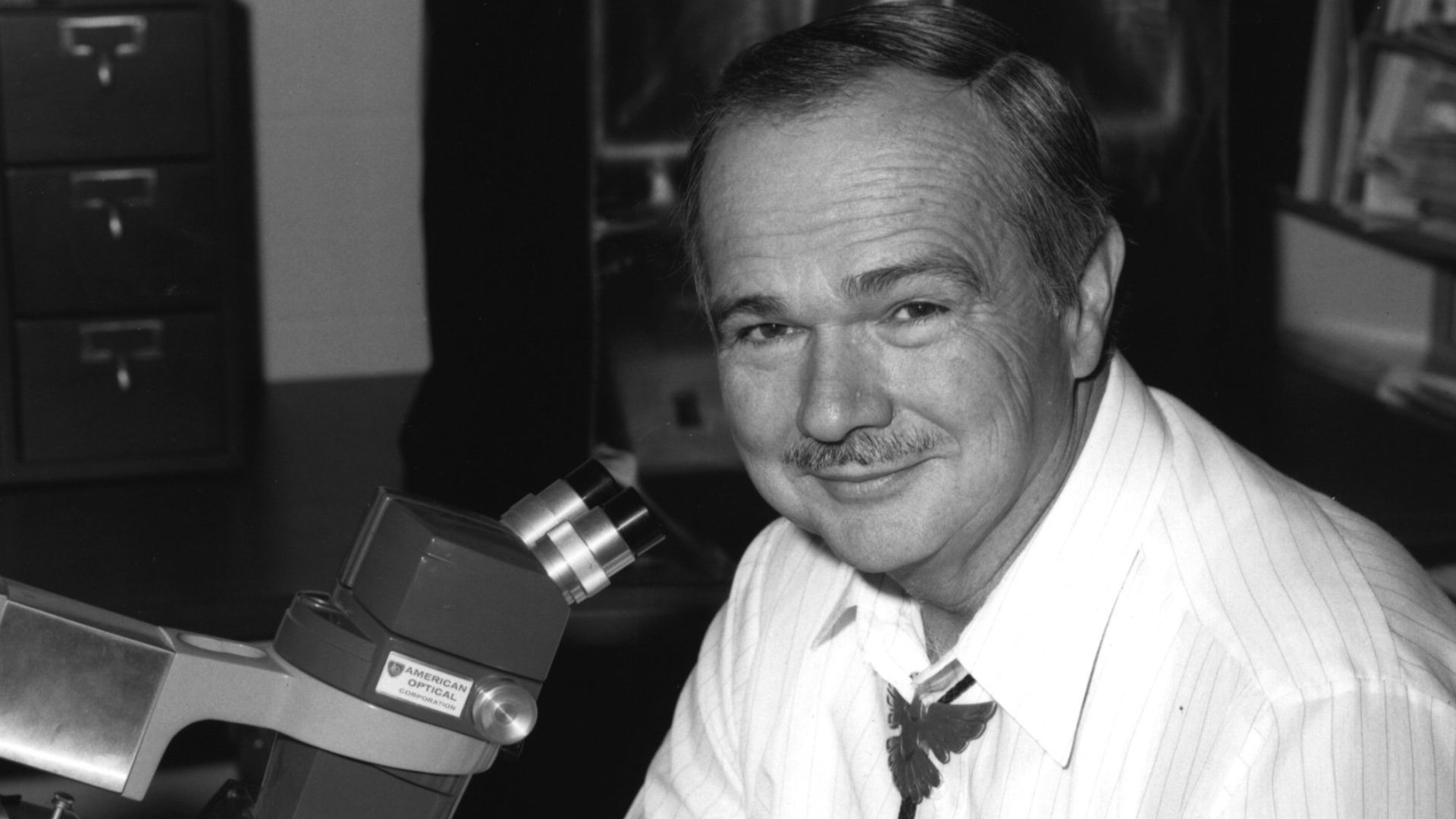

A Life Written In Rock And Starlight

Born in Los Angeles in 1928, Shoemaker’s family frequently moved cities from LA to NYC to Buffalo, etc. Due to his family’s frequent moves, he was exposed to diverse landscapes and rocks, which sparked a growing curiosity. And that fascination was nurtured by science programs at the Buffalo Museum of Education.

Pubdog (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Pubdog (talk), Wikimedia Commons

A Life Written In Rock And Starlight (Cont.)

After joining the School of Practice in the fourth grade, he started collecting mineral samples and soon began attending high-school-level evening classes. In 1942, the family returned to Los Angeles, where Gene completed his secondary education in only three years and worked as an apprentice lapidary during the summer.

Studying Earth At Caltech

By the time he was 16, Shoemaker was already walking through the gates of the California Institute of Technology. Geology became his chosen path, and by 1947, he held his bachelor’s degree. Under skilled mentors, he balanced fieldwork and lab studies, even researching uranium deposits tied to wartime demands.

Canon.vs.nikon, Wikimedia Commons

Canon.vs.nikon, Wikimedia Commons

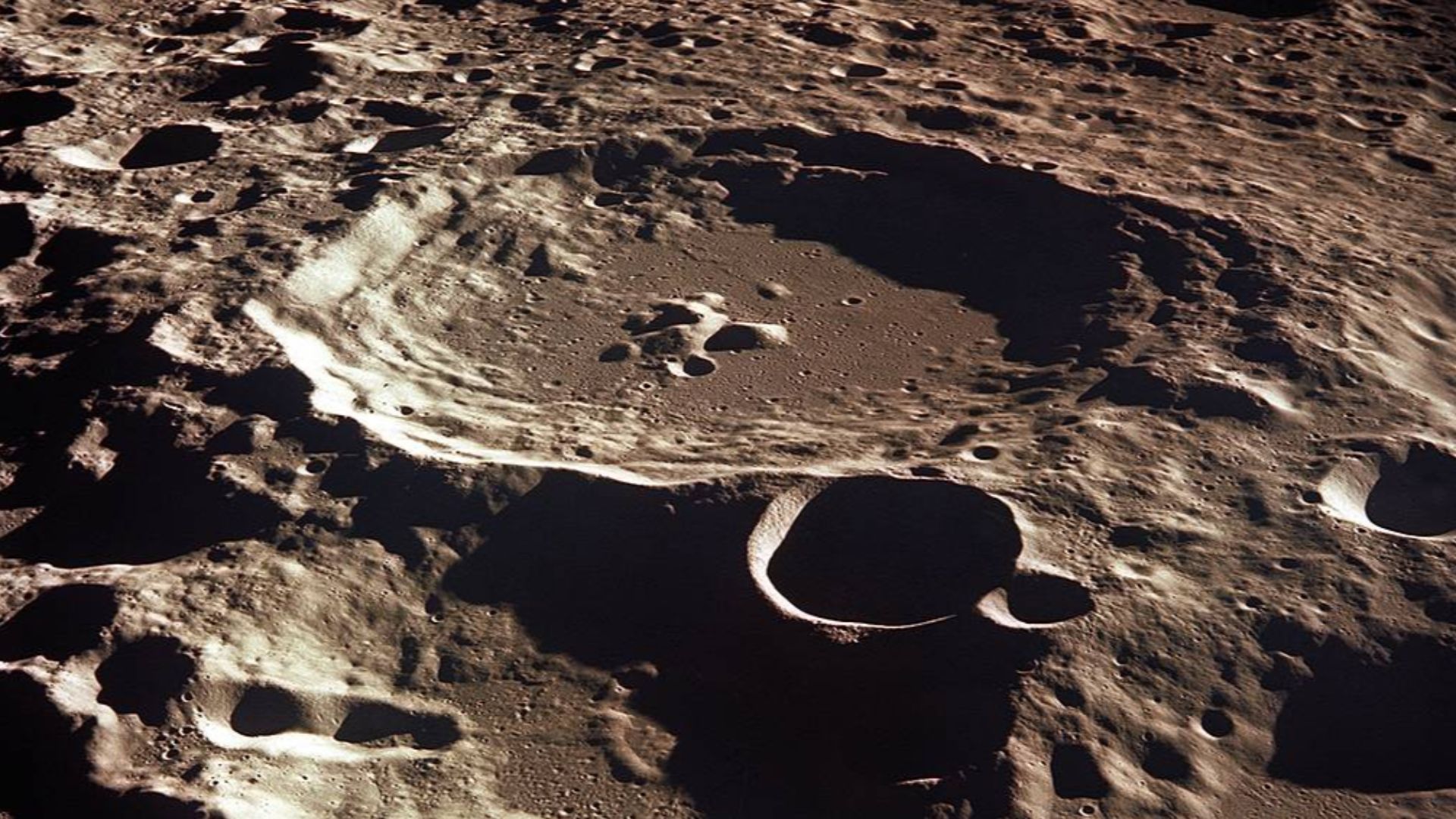

Turning Toward The Moon

In the 1950s, Shoemaker argued that craters formed from impacts rather than volcanoes. He viewed the Moon as a record of solar system collisions, its surface preserving violent events erased on Earth. This bold vision of lunar geology emerged years before the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was even created.

The US Geological Survey Years

Shoemaker joined the United States Geological Survey in 1948. There, he headed uranium exploration during the Cold War. Rugged fieldwork sharpened his mapping and sampling methods, which later became the very skills astronauts would rely on during training for missions far from Earth.

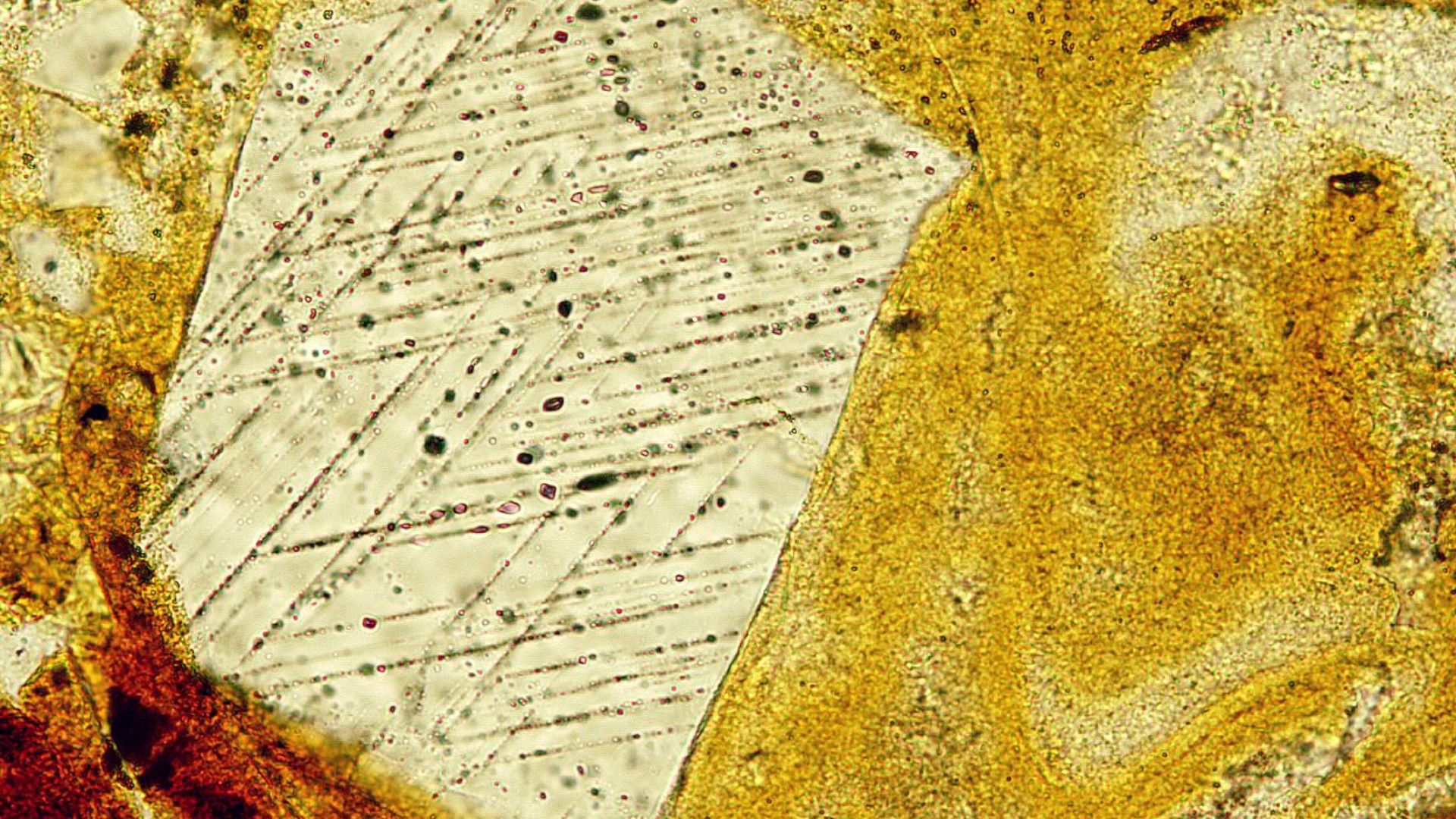

Meteor Crater Discovery

In 1960, Shoemaker proved that an asteroid impact carved Arizona’s Meteor Crater. And his discovery of shocked quartz sealed the case. For decades, people had blamed volcanoes, but his work flipped the explanation. It rewrote textbooks and turned impact science into a serious business.

Martin Schmieder, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Schmieder, Wikimedia Commons

Meteor Crater Discovery (Cont.)

He then tied his Arizona results to the Moon’s battered face. If Earth had been hit, so had the Moon. The research showed that impacts shaped both worlds. With that, impact geology gained new respect and became a vital branch of planetary science.

The Birth Of Planetary Geology

What started as a desert project in 1963 rewrote the story of space exploration. Shoemaker’s Astrogeology Research Program in Flagstaff used telescopic photos to chart the Moon in detail. His fusion of geology and astronomy placed NASA’s lunar training hub right in Arizona.

Deborah Lee Soltesz, USGS Astrogeology Research Program, Wikimedia Commons

Deborah Lee Soltesz, USGS Astrogeology Research Program, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

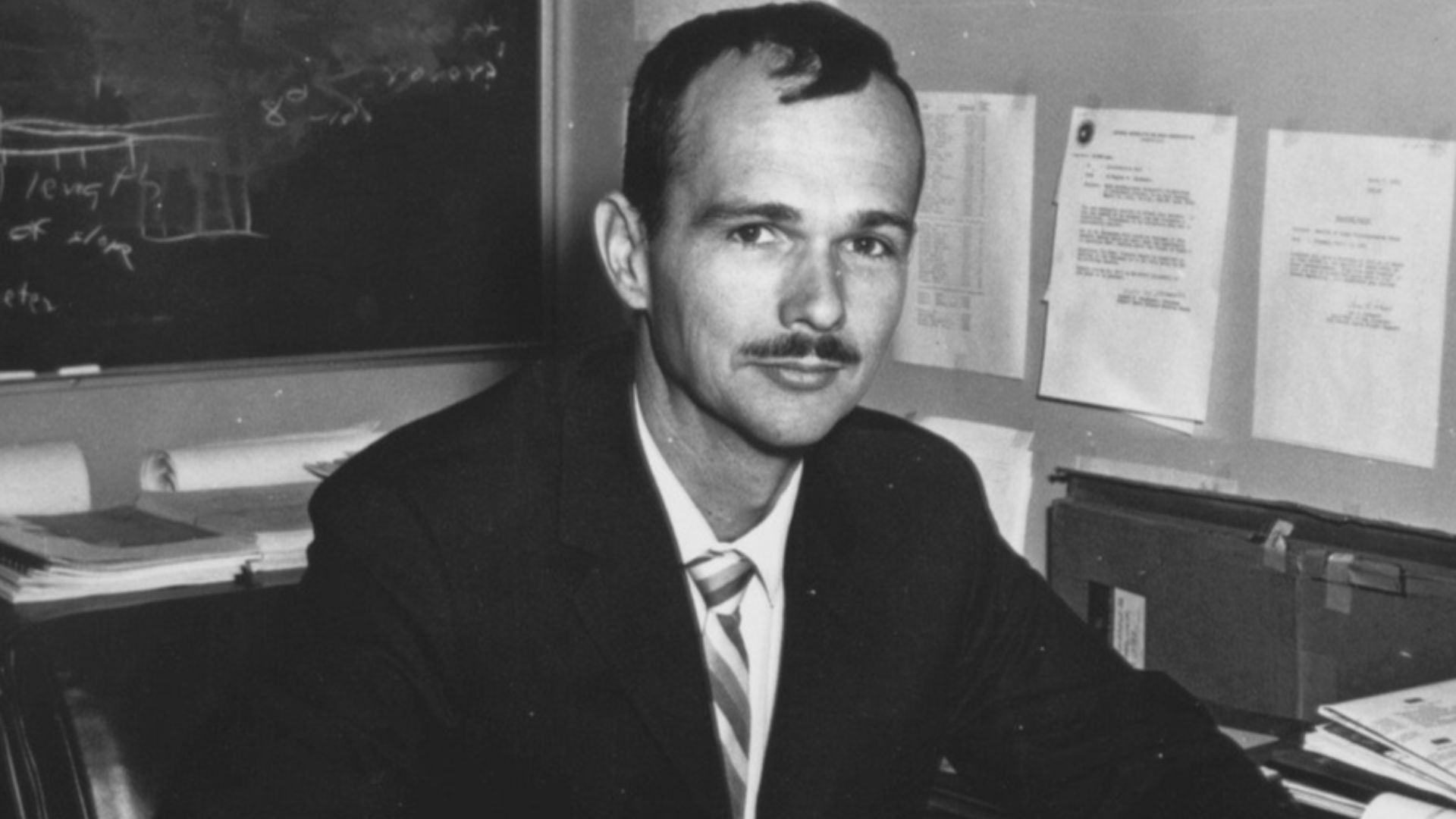

NASA Calls On Shoemaker

When NASA prepared Apollo’s science program, Shoemaker became chief of Astrogeology. He set out clear sampling priorities and insisted that pilots train as geologists. His push ensured astronauts would not just plant flags but return with evidence that could transform humanity’s understanding of the Moon.

William Phinney, Wikimedia Commons

William Phinney, Wikimedia Commons

Training Apollo Astronauts

Field trips turned astronauts into students of geology. At Meteor Crater and Hawaiian lava flows, crews practiced identifying rocks under pressure. Shoemaker drilled them to recognize what mattered most. These lessons later guided their choices on the lunar surface and paid off in priceless samples.

Training Apollo Astronauts (Cont.)

Spacewalks could overwhelm even the best pilots. So, Shoemaker solved that with structured checklists and clear sampling routines. His training helped astronauts gather the right rocks and move with efficiency. The same approach later directed explorations far from Earth’s familiar Moon.

Grounded By Health Issues

A diagnosis of Addison’s disease meant Shoemaker required constant medication. That’s why NASA’s strict health rules barred him from flying, ending his hope of reaching the Moon. But he made that disappointment his fuel—he redirected his passion into leadership and helped define Apollo’s scientific goals.

Directing Apollo Geological Missions

At mission control, Shoemaker led geology teams that guided astronauts during moonwalks. He introduced lightweight sampling tools that made collecting rocks easier. By lobbying for longer surface stays, he opened the door to broader exploration zones and richer scientific returns from the Apollo missions.

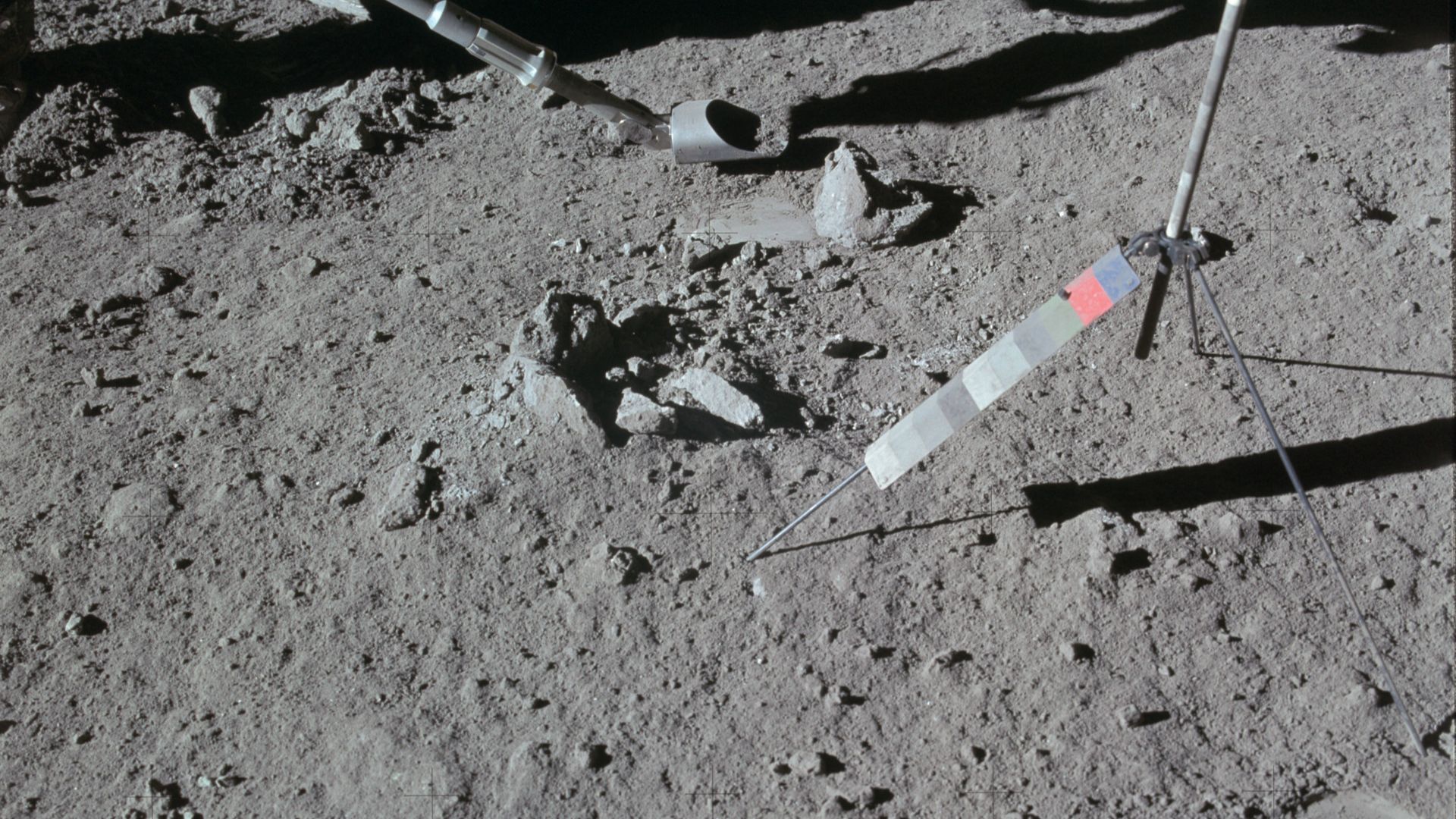

The Rocks That Changed History

Apollo missions carried back treasures in the form of lunar rocks. Tests showed craters formed by impacts, not volcanoes, which again proved Shoemaker right. Dating revealed the Moon’s crust to be over 4 billion years old, and the same rocks confirmed that Earth and Moon once shared a common origin.

From The Moon To Asteroids

When Apollo ended in 1972, Shoemaker’s gaze turned outward. He focused on asteroids, particularly those that crossed Earth’s orbit. Long before planetary defense became policy, he warned of their danger. His work built global ties between astronomers and geologists studying cosmic threats.

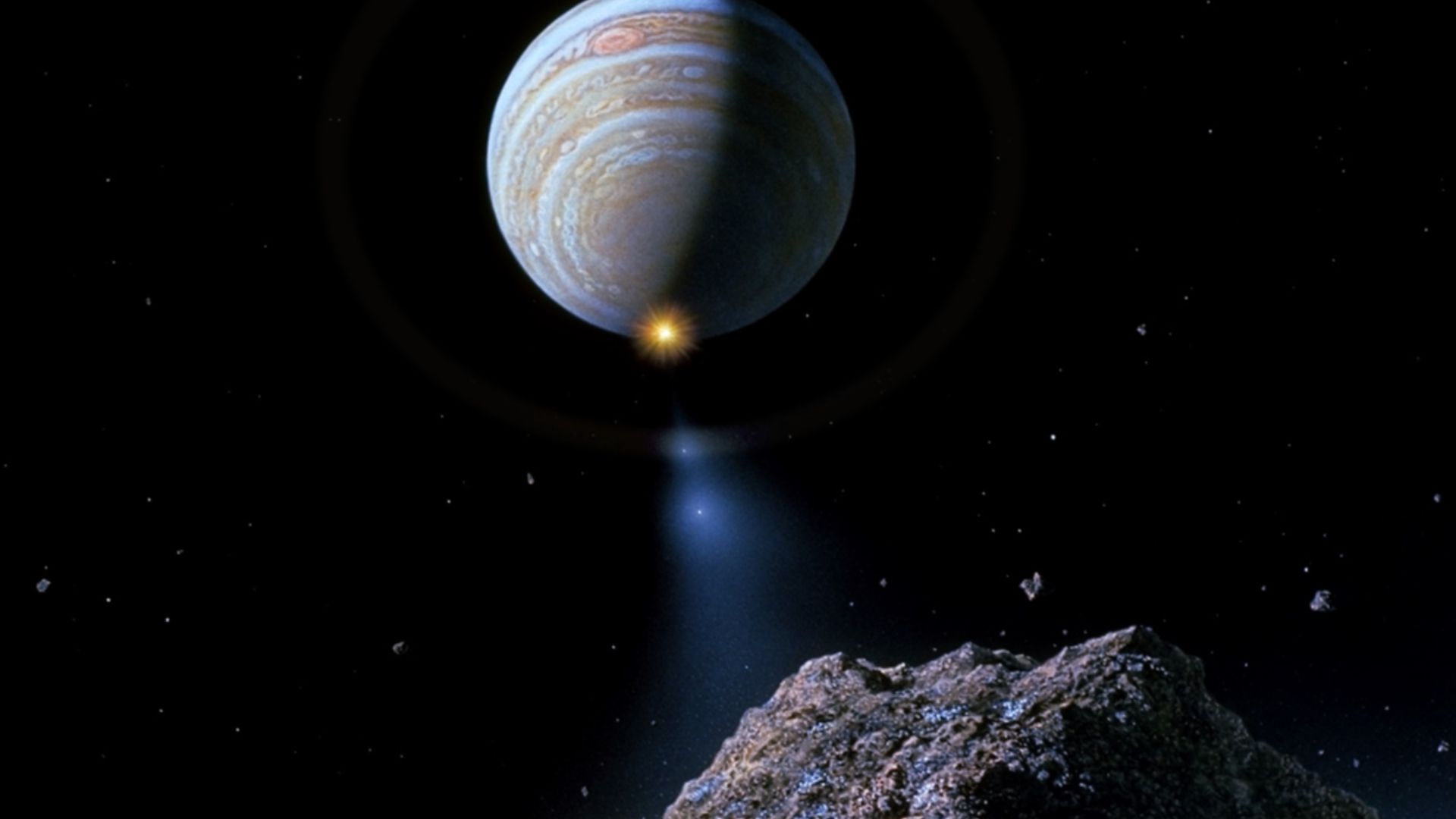

Discovery Of Shoemaker-Levy 9

In 1993, Shoemaker teamed with his wife, Carolyn Shoemaker, an accomplished astronomer, and David Levy, a Canadian amateur astronomer, to spot a new comet. It was torn apart after Jupiter’s gravity pulled it in, sending fragments on a calculated collision course. This discovery crowned his decades of impactful research.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Discovery Of Shoemaker-Levy 9 (Cont.)

The prediction proved correct the following year. In July 1994, fragments of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 struck Jupiter as telescopes on Earth watched. It was the first observed planetary collision in history, a spectacle that confirmed Shoemaker’s warnings and sealed his reputation as the master of impact geology.

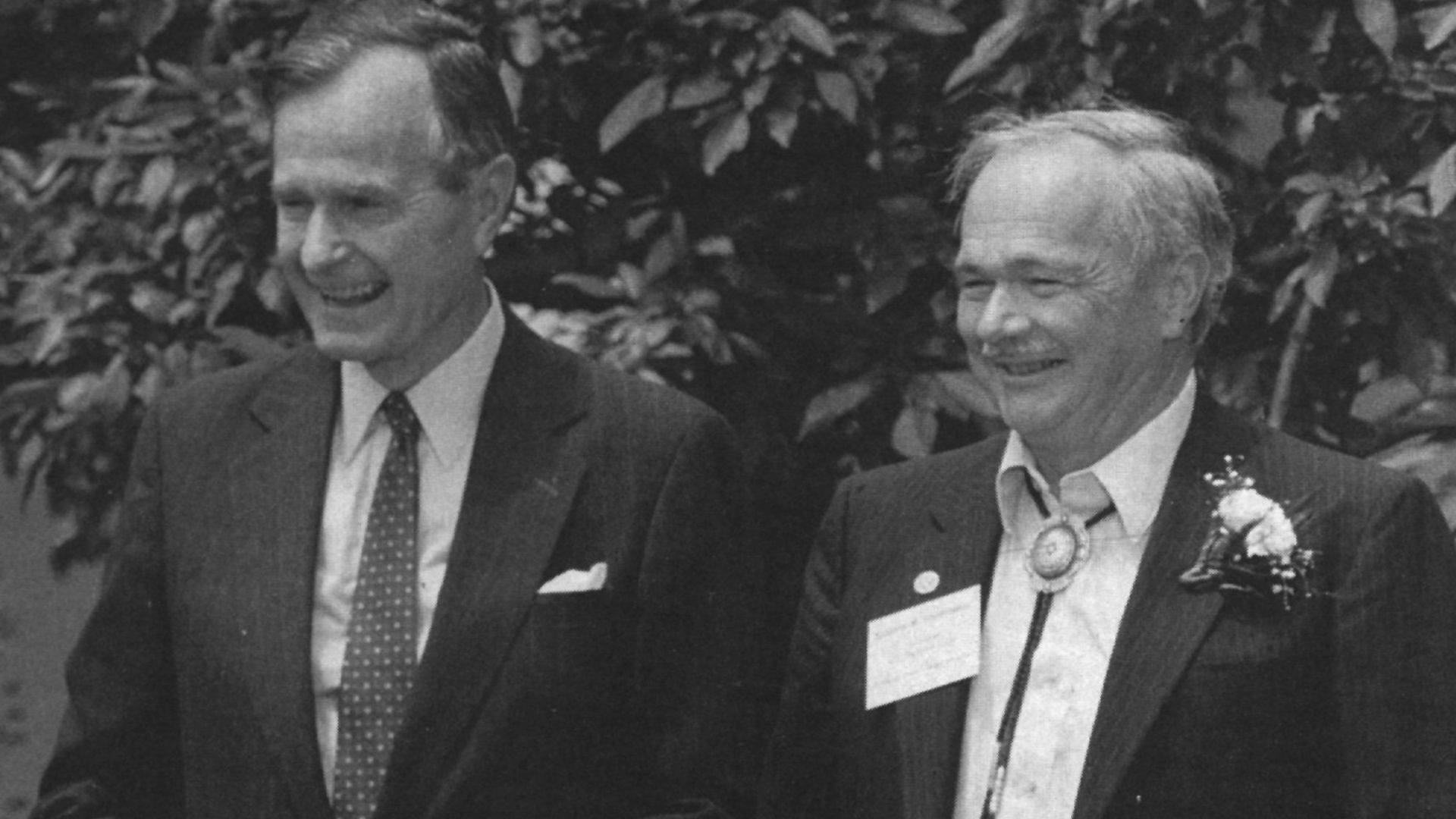

Recognition And Awards

Shoemaker’s career was filled with honors. NASA awarded him the Medal for Scientific Achievement in 1967. In 1992, he received the National Medal of Science. Craters on the Moon and asteroids in space now bear his name, tributes to his unmatched influence.

Chasing Craters Worldwide

Shoemaker spent decades tracking Earth’s scars from ancient impacts. He studied sites across Australia, piecing together evidence like a detective. Each confirmed crater deepened the story of cosmic bombardment and inspired young researchers to carry planetary geology into the future.

The 1997 Australian Expedition

That same dedication carried him into the outback in 1997. With Carolyn by his side, he studied Wolfe Creek and Henbury craters in detail. The trip highlighted both his lifelong devotion to impact science and the unending teamwork with his beloved.

Keraunoscopia, Wikimedia Commons

Keraunoscopia, Wikimedia Commons

A Tragic Outback Accident

On July 18, 1997, tragedy struck on a lonely road near Alice Springs. A car crash ended Shoemaker’s life instantly, but Carolyn survived with serious injuries. News of his passing rippled through the space science world, as one of its brightest voices was silenced.

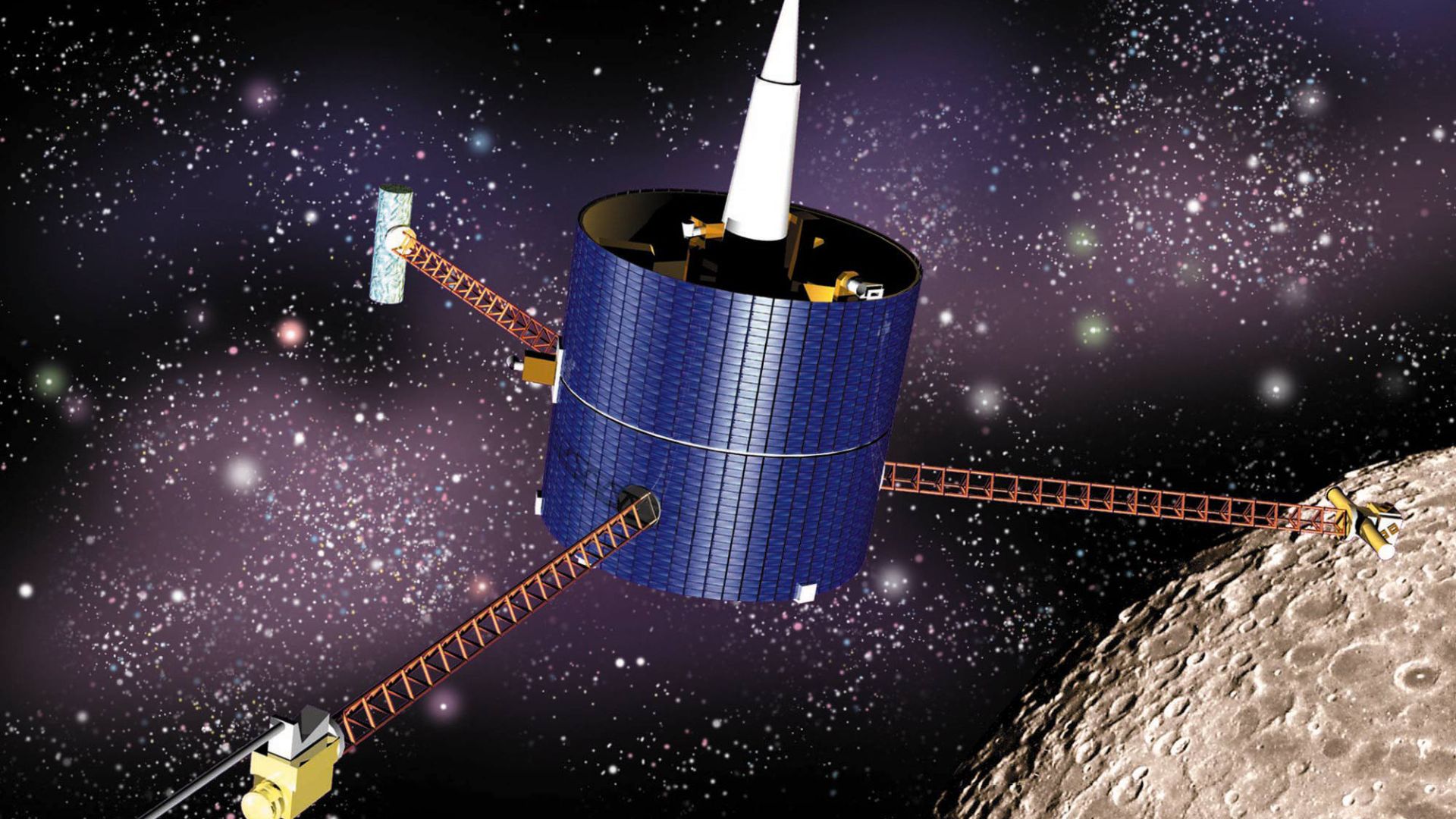

The Lunar Prospector Mission

Just a year after his death, NASA created an extraordinary memorial. A capsule of Shoemaker’s ashes rode aboard the 1998 Lunar Prospector. The container bore engravings of Meteor Crater and Comet Hale-Bopp, two celestial touchstones of his scientific journey.

The Lunar Prospector Mission (Cont.)

Shoemaker long dreamed of reaching the Moon. And that dream came true symbolically on July 31, 1999, when Lunar Prospector crashed near the south pole, carrying his ashes. He became the first person laid to rest on lunar soil—a tribute embraced by all.

Shoemaker’s Final Legacy

His discoveries shaped planetary defense and the study of craters. Generations of scientists he trained continue to expand planetary geology worldwide, and the methods he pioneered still direct today’s missions. His lunar burial symbolizes humanity’s relentless drive to explore and to learn.