Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Baiae once served as the ultimate escape for Rome’s wealthiest citizens, a coastal retreat where politics faded into the background and pleasure took center stage. Set along the Bay of Naples, the resort city offered warm waters, mineral springs, and cliffside villas designed to impress as much as they comforted. Over time, much of this lavish world slipped beneath the sea, leaving behind little more than rumors and scattered ruins. Recent dives, however, have brought Baiae back into focus after underwater archaeologists mapped submerged structures and revealed a remarkably preserved Roman mosaic floor. The discovery transforms Baiae from a distant historical footnote into something immediate and tangible. It also links modern technology with ancient craftsmanship by allowing researchers to reconstruct how Rome’s elite lived when away from public life. This article explores Baiae’s rise as a luxury resort, examines the mosaic uncovered beneath the waves, and explains why the site continues to matter centuries after its disappearance.

Baiae — Rome’s Sunken Resort City

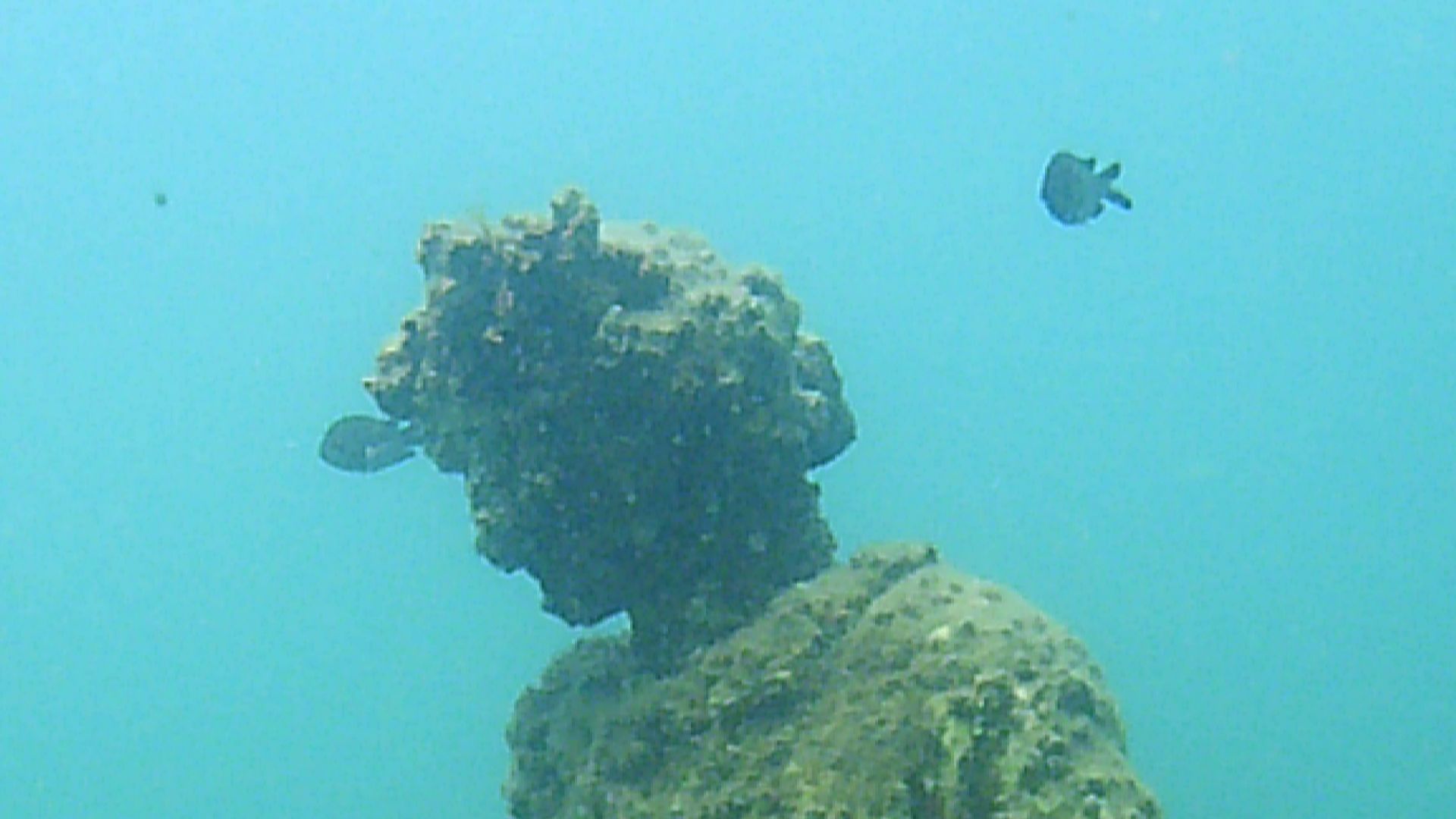

At its height, Baiae held a reputation that blended wealth and influence. Emperors such as Julius Caesar, Augustus, and Nero maintained residences there, drawn by the city’s natural hot springs and its distance from Rome’s political pressures. Villas stretched along the coastline, featuring private bathing complexes, terraces overlooking the sea, and architectural flourishes meant to signal status rather than restraint. Ancient writers even frequently referenced Baiae as a place where social norms loosened, which reinforced its image as a playground for the powerful. Yet the same volcanic forces that heated the springs beneath the city also shaped its downfall. Gradual land movement, known as bradyseism, caused sections of Baiae to sink over time, while earthquakes accelerated the process. Rather than erasing the city, the sea preserved it. Today, Baiae exists as an underwater archaeological park where streets, statues, and villa floors remain largely intact, offering rare insight into Roman leisure culture beyond formal public spaces.

Mentnafunangann, Wikimedia Commons

Mentnafunangann, Wikimedia Commons

The Mosaic Floor Beneath the Waves

Among Baiae’s submerged remains, the recently documented mosaic floor offers one of the clearest windows into elite domestic life. Discovered within a villa complex, the floor likely belonged to a reception or living space designed for social gatherings. Its geometric patterns, formed from intricately cut marble pieces (opus sectile), still show distinct color contrasts despite centuries underwater. Certain sections feature elaborate geometric motifs, though scholars continue to study the designs. The mosaic’s survival reflects its unusual setting. Covered by sediment and shielded by seawater, the surface escaped the erosion, rebuilding, and foot traffic that often damage land-based ruins. Modern archaeological methods made its documentation possible. Divers relied on underwater mapping, photogrammetry, and three-dimensional modeling to record the site without physical disturbance. The mosaic functioned as more than decoration. It communicated wealth and cultural literacy, reinforcing how art shaped social identity inside Roman villas.

What makes the mosaic especially striking is its sense of stillness. Unlike museum pieces removed from their original context, this floor remains where it was first laid, fixed within the structure of the villa itself. Light filters through the water and shifts across the surface, changing how the patterns appear throughout the day. That movement alters interpretation in subtle ways, reminding researchers that Roman interiors were never static environments. Rooms were shaped by light, sound, and social presence. Encountering the mosaic underwater restores part of that experience, even if unintentionally.

Cultural and Archaeological Significance

The mosaic floor sharpens how Roman leisure culture is understood by grounding it in a real, domestic space rather than an abstract idea of luxury. Baiae shows that retreat carried its own social weight, shaped by privacy, setting, and how time was spent away from public responsibility. The underwater ruins feel different from land-based sites because the past is encountered through movement and immersion, not observation from a distance. Visitors also experience the remains as part of an active environment instead of a sealed display. Interest from divers and researchers continues to grow, which has quietly expanded Baiae’s role as a research site beneath the sea. Preservation, however, remains fragile. Exposure to saltwater slowly alters surfaces, and human contact accelerates that process. Protecting the mosaic demands restraint as much as attention. Its continued presence speaks to survival through circumstance, not design, and to history’s ability to endure in unexpected places.