Archaeologists working at Tuna el-Gebel in Minya, Egypt, uncovered an extensive catacomb containing millions of mummified ibises. The site, part of an ancient necropolis, dates primarily to the Late Period and Ptolemaic era (roughly 664–250 BC). Researchers identified long underground galleries filled with earthen jars and limestone coffins that once held birds offered to the god Thoth (National Geographic, 2019).

The necropolis is considered one of the largest animal burial sites ever discovered. Excavations revealed over six miles of tunnels stacked with mummified remains. This massive collection indicates a sustained ritual practice lasting several centuries rather than a single event or isolated custom.

The Role Of The Sacred Ibis

The African Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis aethiopicus) held deep religious significance in ancient Egypt. It was associated with Thoth, the deity of writing and measurement. Worshippers purchased bird mummies as votive offerings, believing each one served as a personal prayer or act of devotion.

Archaeological evidence suggests these offerings were part of a standardized temple system that received, embalmed, and interred the birds in enormous numbers (Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 2018).

Millions of ibis mummies have been documented across Egypt, but the density at Tuna el-Gebel is exceptionally high. Each bird was wrapped and placed in pottery vessels or wooden coffins before being stored in vast underground chambers. The production scale indicates a well-organized operation involving priests, embalmers, and suppliers who maintained a steady flow of animals for ritual demand.

Bj.schoenmakers, Wikimedia Commons

Bj.schoenmakers, Wikimedia Commons

How Were The Birds Obtained?

For decades, scholars debated whether ancient Egyptians bred ibises on temple farms or captured them in the wild. Recent DNA analysis of preserved tissue samples provided new insight.

A study published in PLOS ONE titled Mitogenomic diversity in Sacred Ibis Mummies sheds light on early Egyptian practices (2019) found genetic diversity in the mummies consistent with that of wild populations. This suggests means the birds were trapped seasonally rather than bred in captivity.

Archaeologists believe temples may have established short-term holding areas to keep birds before mummification. Wetland regions along the Nile provided ideal habitats where large flocks could be captured during migration seasons. This method would have supplied a continuous source of birds without extensive breeding facilities.

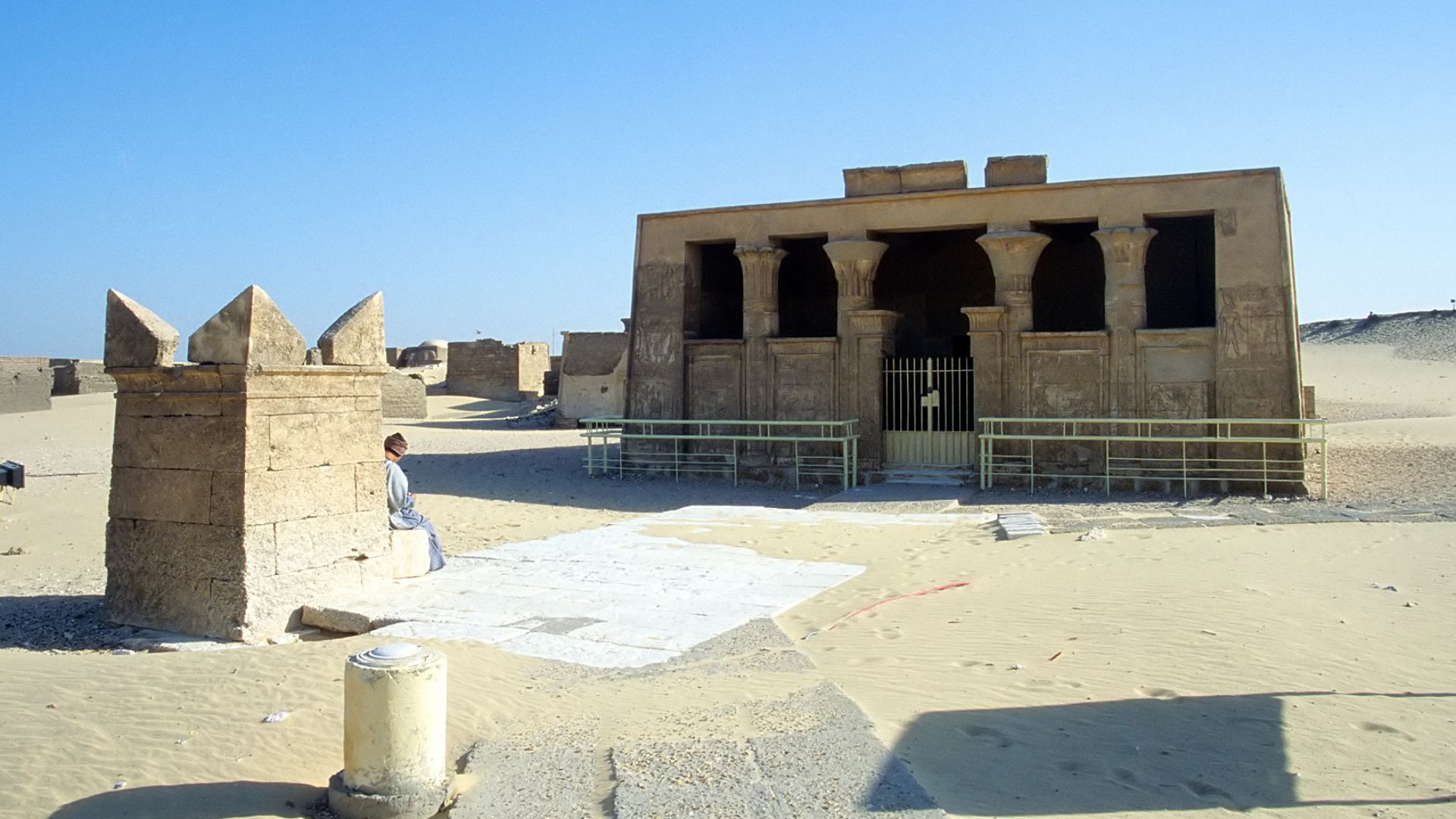

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

An Industry Of Faith And Economy

The ibis-mummification trade formed a complex system linking religion and commerce. Temples sold prepared mummies to worshippers seeking divine favor, and the proceeds likely funded temple operations. Workers specialized in embalming, linen wrapping, pottery production, and tunnel excavation, all supported by local agriculture that provided oil, resins, and cloth according to the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities.

Researchers estimate that millions of ibises were sacrificed across Egypt each year during the height of the practice, based on archaeological findings and scholarly consensus. A 2019 PLOS ONE study by Wasef et al. used mitogenomic analysis to examine the birds’s remains, revealing high genetic diversity consistent with mass seasonal capture rather than organized breeding.

The Tuna el-Gebel site alone may contain several million individuals. These findings illustrate how religious devotion influenced local economies and resource use.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

A Window Into Ancient Ritual Systems

The discovery at Minya expands understanding of how ancient Egyptian religion operated beyond temple walls. It demonstrates the logistical capacity of priestly institutions and the scale of faith-driven industries. The Ibis catacombs of Tuna el-Gebel reveal a society where belief, trade, and natural ecosystems were closely linked.