Postcard From Hell

The Battle of Passchendaele was a series of bloody clashes fought in miserable conditions, a grim picture postcard of the relentless, grinding brutality of World War I. Although the bravery of many valiant men is clear, the campaign was controversial, with victory short-lived.

Long Shot

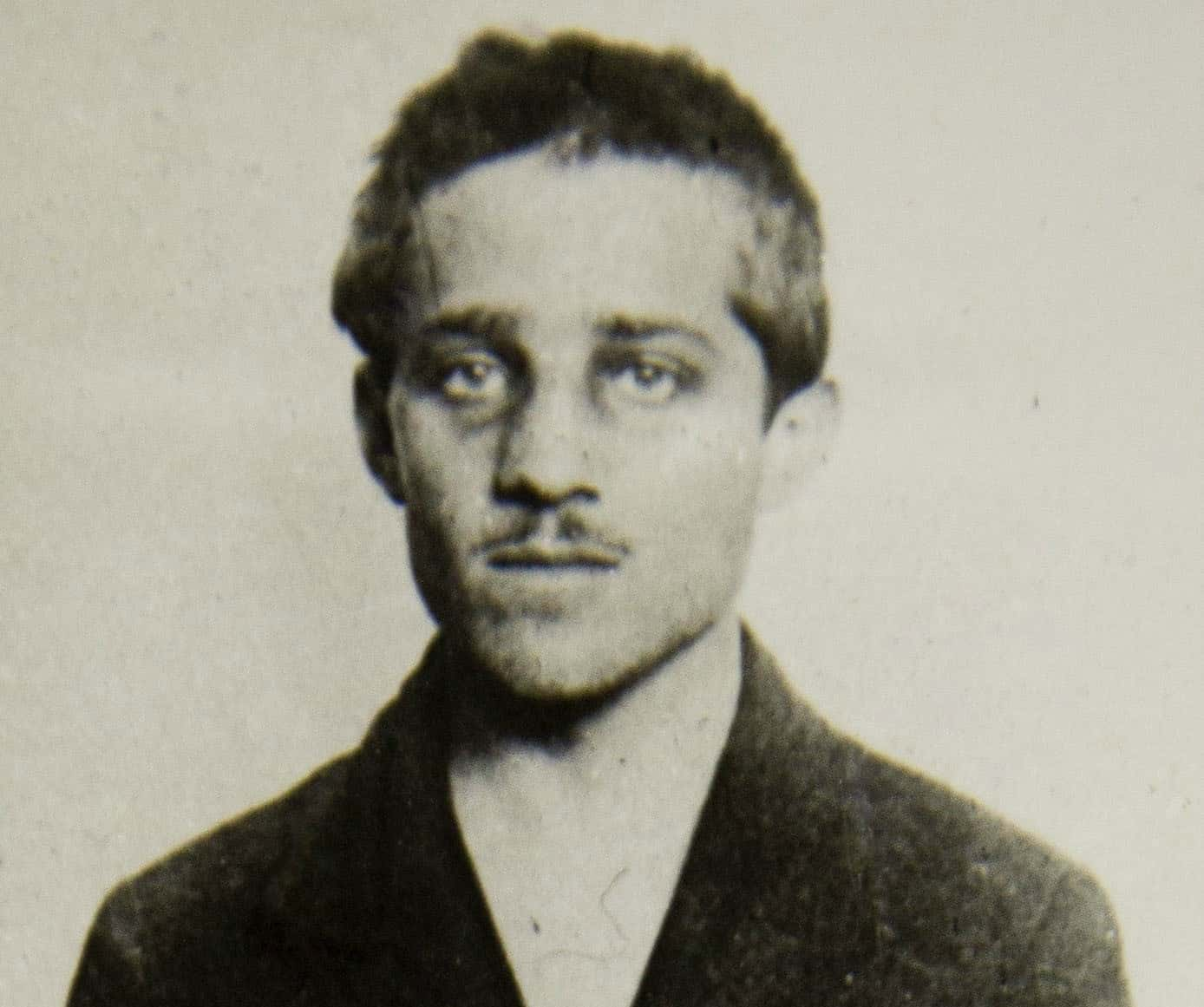

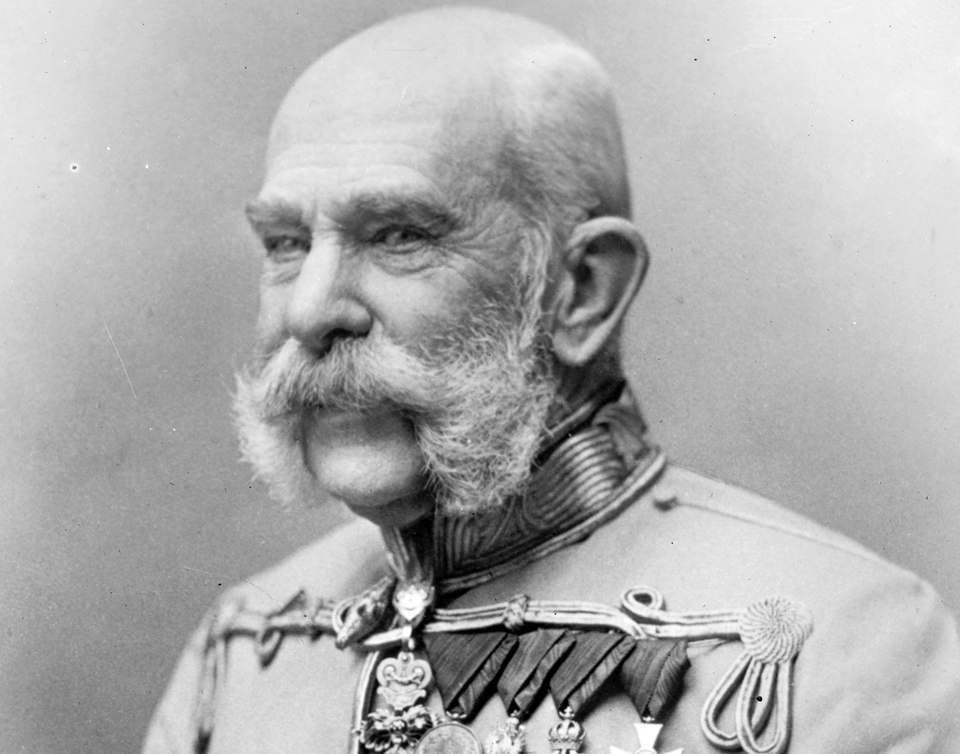

Below the surface, WWI had many causes, but an assassination by a lone attacker unleashed unstoppable forces. A Bosnian Serb, Gavrilo Princip, shot Archduke Franz Ferdinand, first in line to rule the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914.

Domino Effect

Austria-Hungary then declared war on Serbia. Russia prepared to defend Serbia, so Germany, Austria-Hungary’s ally, declared war on Russia, and on France, Russia’s ally, for good measure. After Germany invaded neutral Belgium on its way to capture France, Britain declared war.

Studio of Károly Koller, Wikimedia Commons

Studio of Károly Koller, Wikimedia Commons

Britain Declares War

The government was concerned about Germany taking over France, but Britain’s anti-war leaders knew it was easier to justify defending Belgium’s neutrality. Either way, the battle was now on. It was August 1914, and all sides expected this curious conflict to be over soon enough.

Geoff Charles, Wikimedia Commons

Geoff Charles, Wikimedia Commons

Stalemate In The West

German forces quickly invaded France, but were partly pushed back by the Allies. Germany had wanted a quick victory in the west so they could shift men to the east. Instead, bloody battles in hellish trenches followed, and the situation was at a stalemate. Something had to change.

Robert Capa, Wikimedia Commons

Robert Capa, Wikimedia Commons

Sinking Prospects

In the spring of 1917, General Douglas Haig faced two big problems. The British commander knew Germans were using their U-boats to sink merchant ships bringing vital supplies to the United Kingdom. The German submarines had to be stopped or his country would starve.

Losing Hope

The other big problem was mutiny. The Western Front stretched from the North Sea to Switzerland, with France’s border with Germany taking up a huge part of that frontier. A major push by the French army had failed, and many of its weary men were giving up hope.

Cassowary Colorizations, Wikimedia Commons

Cassowary Colorizations, Wikimedia Commons

Time For A Diversion

So, General Haig saw a push to the devastated village of Passchendaele in Belgium as a way to solve both his problems. It would distract German forces from mutinous French positions, and a victory would let him next capture Belgian ports the Germans used to launch their U-boats.

Bain News Service, publisher, Wikimedia Commons

Bain News Service, publisher, Wikimedia Commons

A Salient Feature

Haig had his eyes on the “Ypres salient,” a bulge in the frontline that jutted into enemy lands just east of the Belgian city of Ypres. In the opening months of the conflict, Germany had taken over most of Belgium, so holding onto this territory was a big deal, symbolically and strategically.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Taking The High Ground

By taking control of ridges south and east of Ypres, the Allies could also control a major railway route supplying German forces. The last ridge east of Ypres included Passchendaele, so the ultimate goal of this campaign was now clear: capture the ridges and defend the high ground.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A Poisonous History

The Battle of Passchendaele is also known as the Third Battle of Ypres, because the area had seen action earlier in the conflict. Germany first used poison gas during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915. The allies had been forced to retreat, but still held much of the valley.

Frank Hurley, Wikimedia Commons

Frank Hurley, Wikimedia Commons

Hostile Environment

The Ypres salient was strategically vital because holding it helped defend French ports.

But keeping the toehold, let alone recapturing territory, came with big risks, as the enemy surrounded it from three directions—much of it higher ground. And Haig faced other challenges.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

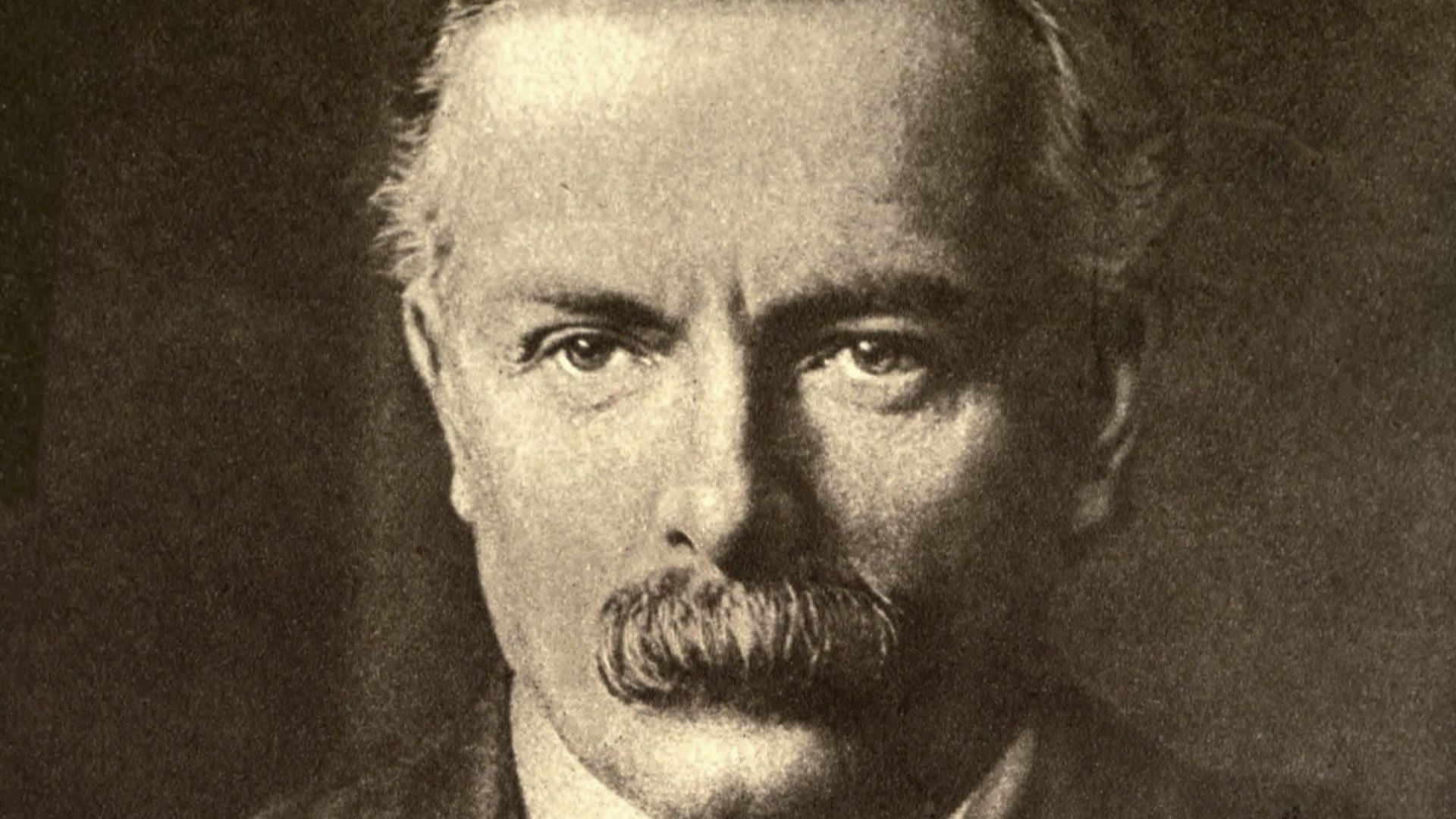

Doubts And Questions

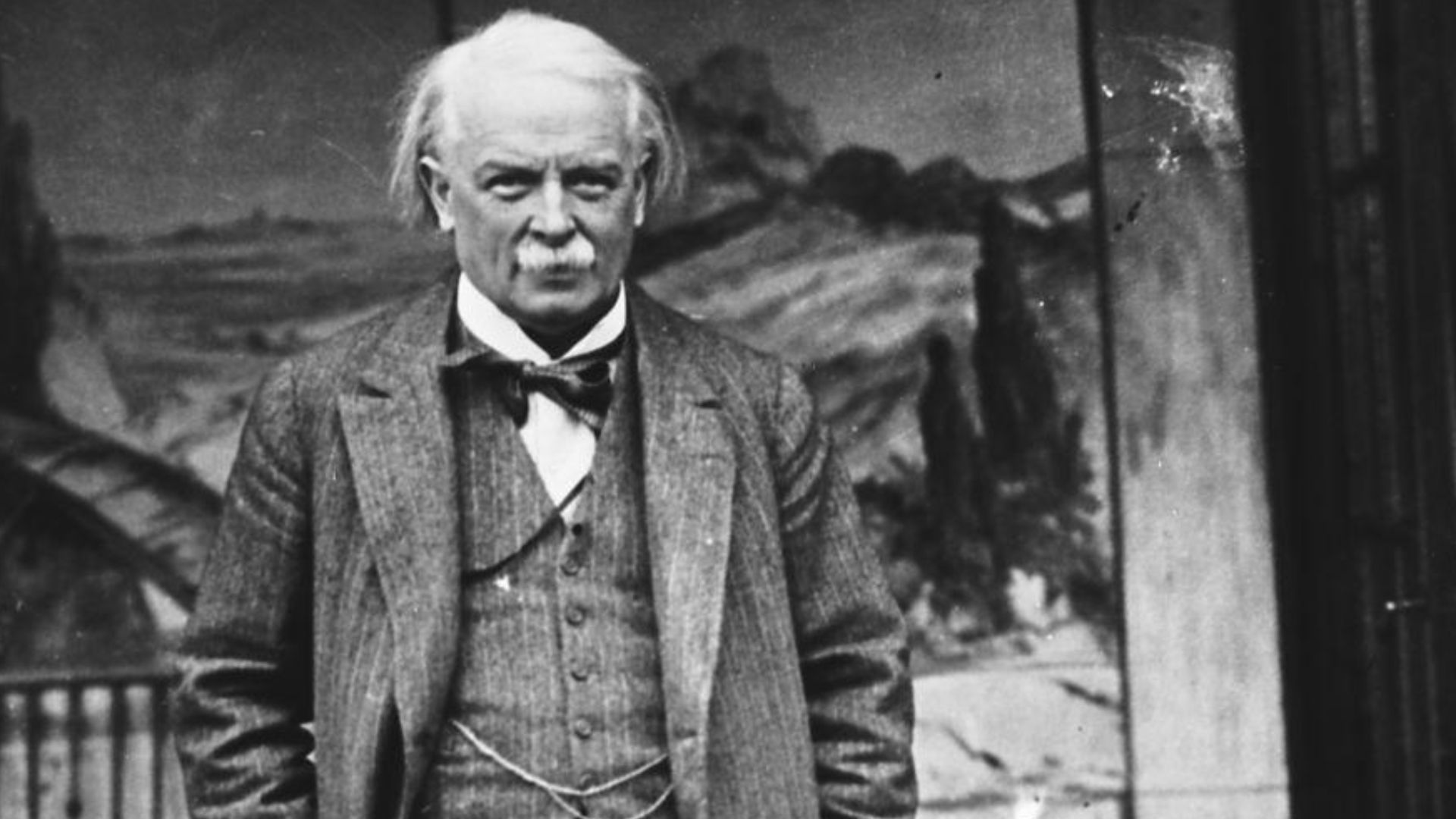

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George had doubts about Haig’s plan. Allied forces were stronger than the Germans’, but only by a small amount, so victory was uncertain. And Haig’s claim that a win at Passchendaele would let him secure Belgian ports seemed too optimistic.

Photo by A. & R. Annan & Sons, Wikimedia Commons

Photo by A. & R. Annan & Sons, Wikimedia Commons

A Question Of Morale

The Allies were also smarting over the failure of the Nivelle offensive in France. Although the British and French succeeded in pushing back German lines, casualties were so high the French forces were left in disarray, which is where Haig’s concern about mutiny came from.

Paul Queste, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Queste, Wikimedia Commons

Grim Agreement

What everyone seemed to agree on was that there would be lots of casualties by the end of this campaign. Despite the doubts and uncertainty, in the end, the British cabinet approved Haig’s ambitious plan for Ypres. And it would soon be time for Canadians forces to get involved.

Bassano Ltd, Wikimedia Commons

Bassano Ltd, Wikimedia Commons

Diverting The Diversion

The Canadian Corps had achieved a spectacular victory at Vimy Ridge in April, capturing most of the German-held ridge in just one day. But instead of going to Belgium right away, they were moved to another part of France in hopes of diverting German attention from Passchendaele.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Opening Volley

In July, British forces started shelling ridges around the Ypres salient in order to weaken German defenses. But the conflict had gone on for nearly three years. Endless trenches had turned into canals beneath Flanders’ rain clouds, and craters had turned into watery graves.

Forbes, Ian, Wikimedia Commons

Forbes, Ian, Wikimedia Commons

Bad Weather

Haig ordered the attack to begin on the last day of the month. But momentum stalled after rain started falling in the afternoon. Artillerymen couldn’t see advancing comrades, so the Germans were able to quickly push back. Within days, the Allies dug in, unable to move through the mud.

Vulnerable Offense

Even when the offensive resumed, the Allies were at a disadvantage. Their goal was to move through a hellish swamp, with supply lines increasingly stretched, while the Germans just had to defend their existing positions, with many of them firing from reinforced concrete “pillboxes”.

Slow Progress

Over the next few weeks, British and French forces attempted to advance in the soggy, muddy quagmire of these Belgian fields as shots and shells cut down Haig’s men. Some 70,000 combatants lost their lives or were wounded. It was looking hard to justify such a price in blood.

Nenea hartia, Wikimedia Commons

Nenea hartia, Wikimedia Commons

Haig Persists

The British Prime Minister wanted to abandon the offensive, but Haig prevailed. In September, he added Australian and New Zealand forces to the meat grinder of his ineffective strategy. Over and over, the Allies would advance, only for Germans to recapture their lost ground.

National Library NZ on The Commons, Wikimedia Commons

National Library NZ on The Commons, Wikimedia Commons

Dangerously Complacent

But now it was the Germans’ turn for excessive optimism. They mistakenly believed the Allies had given up on their offensive in the region, and so, moved much of their ground and air units elsewhere. However, the Allies now had better weather, better supply lines, and a better tactic.

Promising Maneuver

The Battle of the Menin Road Ridge showed off General Herbert Plumer’s new “bite and hold” method. Infantrymen would pierce through a German line at a particular point, then hold a thin ribbon of ground. Another group of fighters would then arrive and stream past the first group.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Fresh Forces

This method let fresh infantry fight the Germans when they finally clashed. The British-led forces were also improving their use of artillery and air power. General Plumer achieved most of his goals on the first day of his attack, and managed to repel three German counterattacks.

Haig’s Misjudgment

Having captured this ridge east of Ypres, Haig could next target Passchendaele Ridge, six miles (10 kilometers) away. But Haig was operating on the mistaken belief that the German army was on the verge of collapse. In fact, the opposite was true, all due to what was happening far away.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Reinforcements Arrive

Russian forces on Germany’s Eastern Front were in a state of confusion amid the fall of the Tsarist regime and the turmoil that followed. With less pressure in the east, Germany could move men to the west, and these reinforcements would make it even harder for the Allies.

Boasson and Eggler St. Petersburg Nevsky 24., Wikimedia Commons

Boasson and Eggler St. Petersburg Nevsky 24., Wikimedia Commons

The Canadian Connection

Haig needed more men and turned his attention to the Canadians. He ordered Lieutenant General Arthur Currie to shift his men, then in France, to lines near the Belgian village of Passchendaele. Currie argued against this move, as he saw a grim toll as inevitable.

University of Victoria Libraries from Victoria, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

University of Victoria Libraries from Victoria, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

Ypres Redux

But Haig was his superior, so Currie obeyed and moved his 100,000 fighting men to Belgium. For some, it was familiar territory. But when Currie arrived, he was appalled.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Wet Graves

The Ypres salient had been under such heavy fire for two years that the remains of combatants and horses still littered the battlefields. Currie instructed bodies to be removed, and ordered road and rail work to make transport easier. Nonetheless, fatal risks lay in wait everywhere.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Deep Craters

When men weren’t being shot at, they could walk along narrow wooden paths, but anyone who lost their footing was in danger. Craters were big enough to drown a horse, and so quite able to submerge a slipping man. But the Canadians persisted and carefully moved into position.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Muddied Waters

On October 26, 1917, the Canadians started the first of four assaults. The impossible conditions meant gains were limited and casualties were high. Mud jammed up equipment, and could even swallow men whole as they slept. Then, four days later, the Canadians advanced again.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Losing Direction

In the muddy chaos, men would get disoriented, not knowing where the front line was. Medics would wade waist-deep to reach the wounded. Infantrymen risked amputation from trench foot. For many young men, loss of life or limb would be their only escape. But then things turned.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Victory At Last

A third assault, this one on November 6, saw a breakthrough. The Canadians repelled the German defenders, reached the ridge, and captured the devastated village of Passchendaele. Another attack, on November 10, secured the last of the high ground. But was it worth it?

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Grim Toll

Currie had estimated 16,000 of his men would be casualties—and he was right. Some 4,000 Canadians lost their lives and 12,000 were wounded. And the entire campaign had seen 275,000 casualties among British-led forces, with a figure of 220,000 for the other side.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Consolation Prize

Haig’s victory did not lead to the Belgian ports and the fearsome German U-boats they harbored. It’s possible the fighting gave the French army a chance to regroup and improve its morale, but in the process, the British-led forces were severely depleted. And it gets worse.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Quiet Retreat

A few months later, the Germans seemed about to counterattack, so British-led forces were ordered to withdraw. All territory gained from the bloody 98-day battle was lost. As Winston Churchill would later say, Passchendaele sapped “valor and life without equal in futility”.

Yousuf Karsh, Wikimedia Commons

Yousuf Karsh, Wikimedia Commons

Distant Prize

Lloyd George said the battle was “one of the greatest disasters” of WWI, and historians are inclined to agree. Allied forces managed to advance five miles (eight kilometers), but those gains were costly—and given up in April 1918 after the Germans launched a spring offensive.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

Maple Leaf Forever

The Battle of Passchendaele did help shape Canada’s future. Prime Minister Robert Borden successfully lobbied for representation at the peace talks that ended the conflict, and Canada signed the treaty separately, even if Borden’s signature was indented under “British Empire”.

William James Topley, Wikimedia Commons

William James Topley, Wikimedia Commons

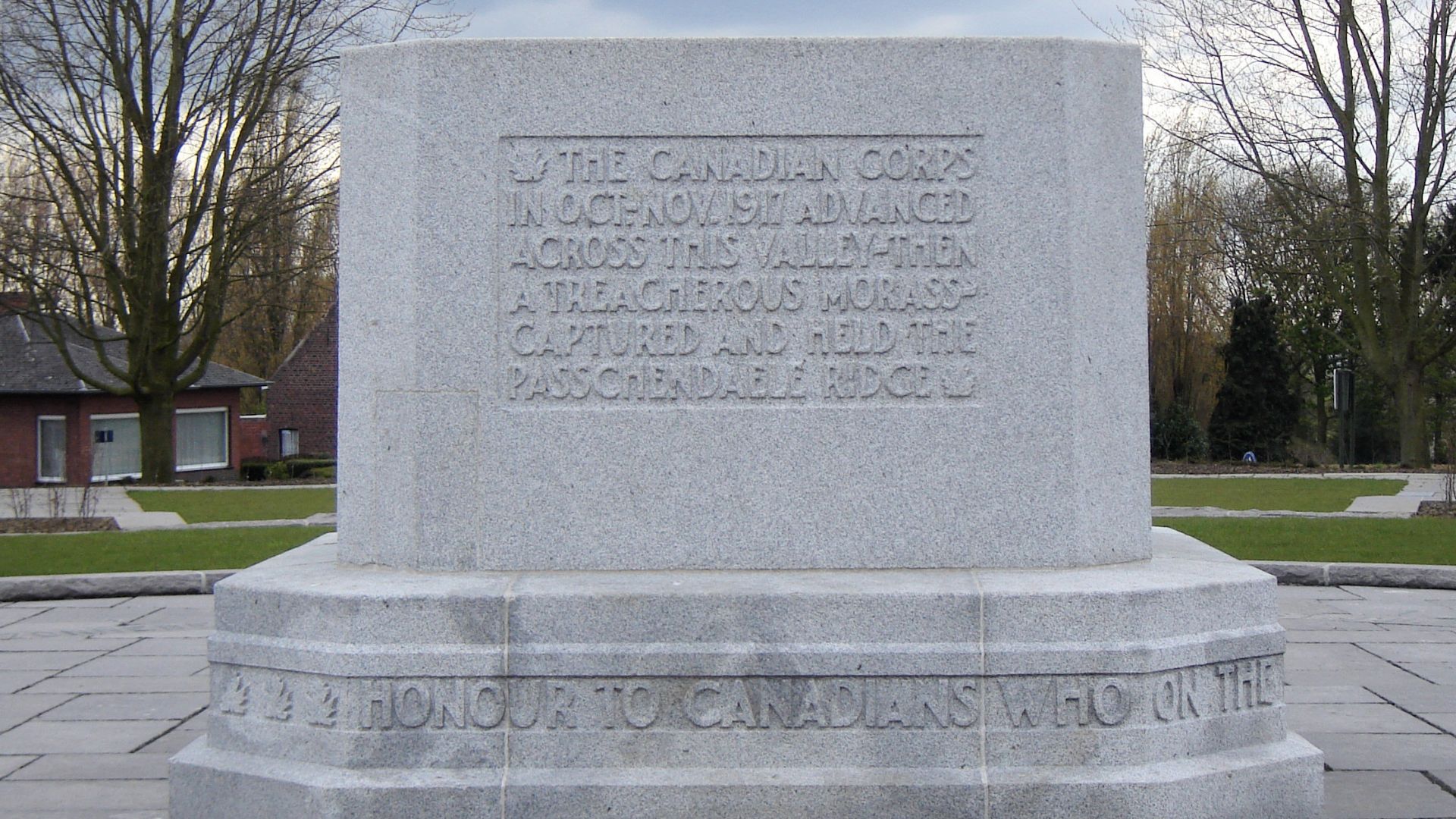

The Morass

The Passchendaele Canadian Memorial, facing a street called Canadalaan, sits in a farm field where much of the heaviest fighting took place. A granite monument notes the valley was “then a treacherous morass”. The nearby New British Cemetery includes Passchendaele burials.

The Beginning Of The End

The Battle of Passchendaele ended on November 10, 1917, a year and a day before the Armistice ceasefire. Germany’s spring offensive in March 1918 had shown promise, but exhausted its army. An Allied counteroffensive in August would scatter the enemy’s front lines.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

The Fall Of Empires

Passchendaele was a tragic chapter in the bloody tale of the “Great War” that rewrote borders and dismantled the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian, and Ottoman Empires. Sadly, this “war to end all wars” ended up doing nothing of the kind, as WWII would soon show in 1939.

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

John Warwick Brooke, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

The Forgotten Heroes Of World War I

The Most Important Events Of WWI

Timeline: The First 10 Days Of WWII

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21