What The Chicago World’s Fair Gave Us

Before smartphones or skyscrapers, one event quietly rewrote the future. Hidden behind neoclassical facades and glowing electric lights, the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair celebrated inventions and ideas that still shape daily life. What emerged from those fairgrounds may surprise you.

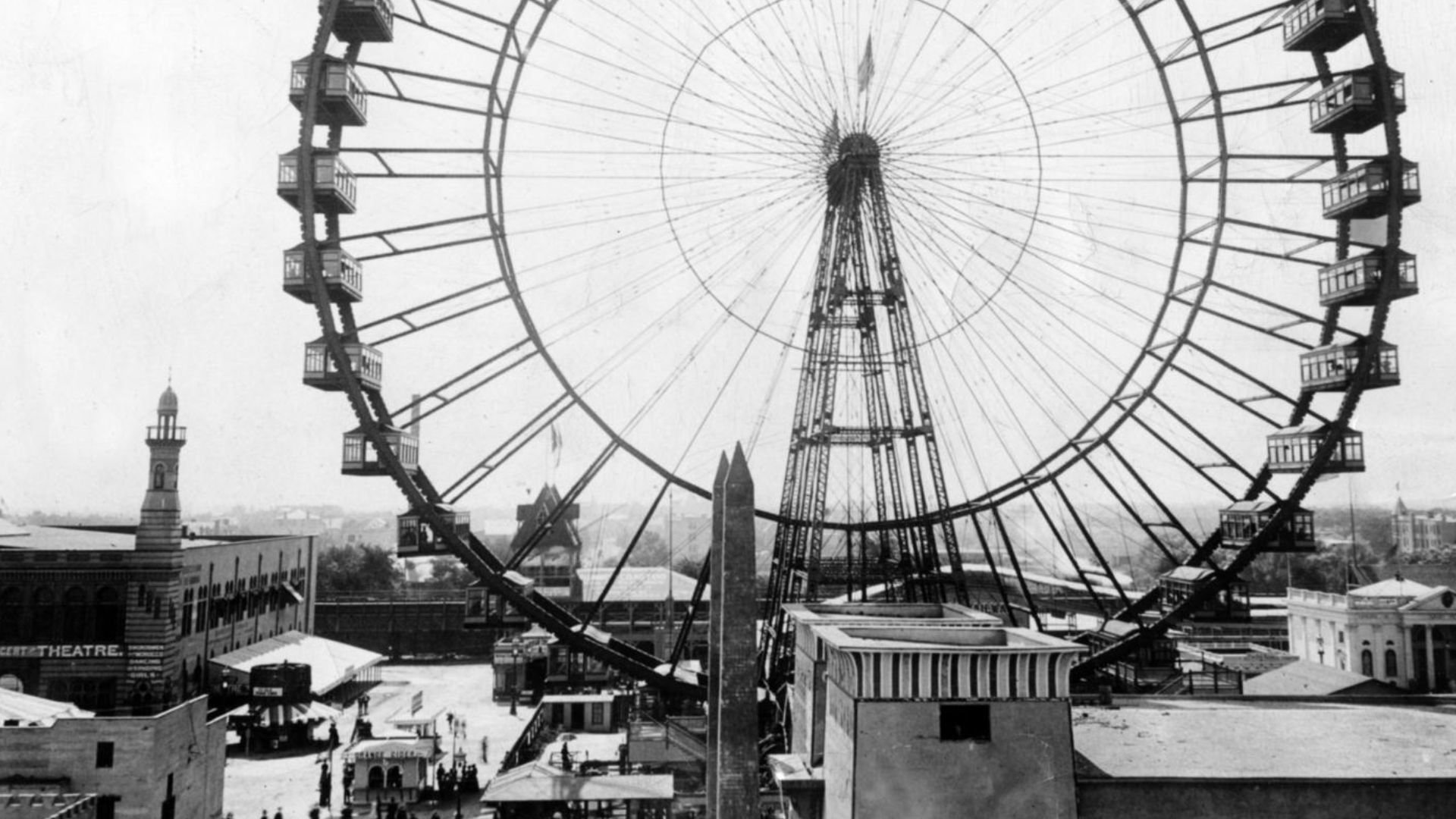

Ferris Wheel

Towering at 264 feet, the original Ferris Wheel debuted at the 1893 World’s Fair as America’s answer to the Eiffel Tower. Designed by George Washington Gale Ferris Jr, it amazed more than one million riders. This monumental steel structure symbolized American ingenuity and influenced future amusement rides.

Alanscottwalker, Wikimedia Commons

Alanscottwalker, Wikimedia Commons

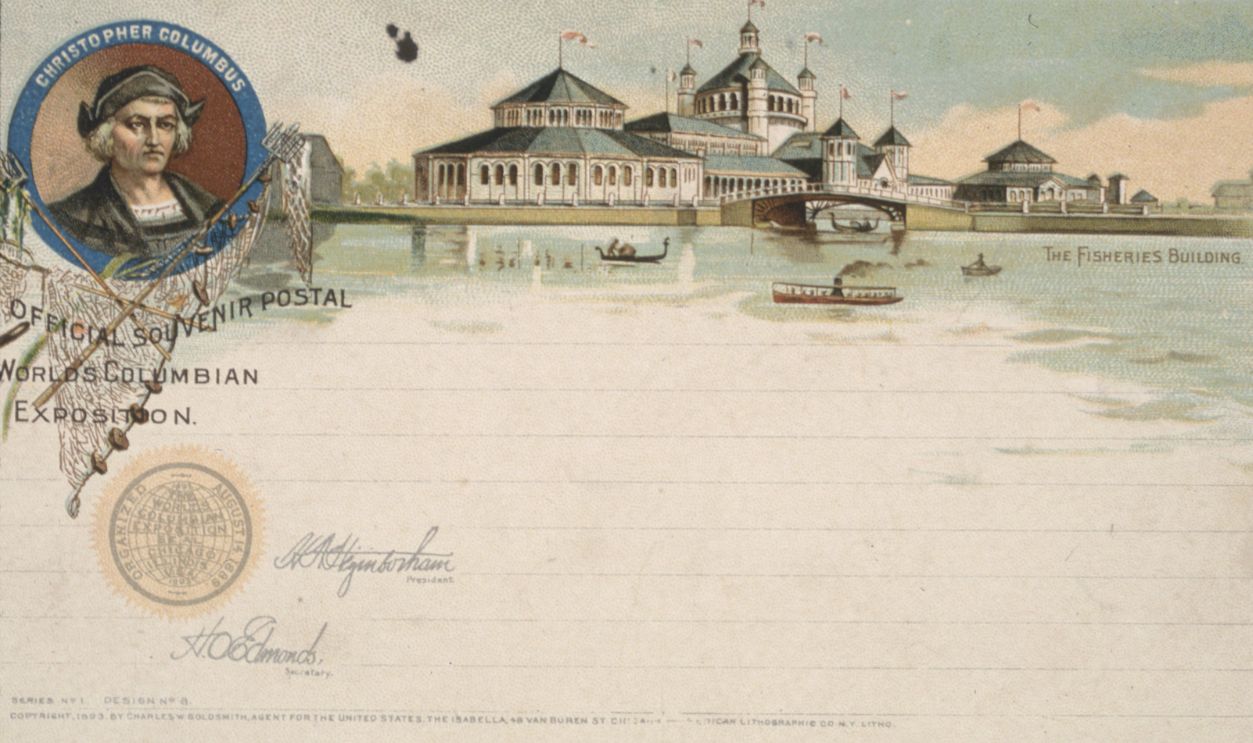

Commemorative Stamps And Picture Postcards

The World’s Columbian Exposition saw the debut of America's first commemorative postage stamps and collectible picture postcards. These items gave visitors tangible keepsakes to mail or collect, igniting a national fascination with stamp collecting and travel mementos. It was a quiet revolution in postal history and souvenir culture.

Houdini’s Magic Act

Although still early in his career, Harry Houdini, alongside his brother Theo, performed escape and sleight-of-hand tricks near the Midway. While not officially billed among the fair’s headliners, their act caught enough attention. It was an important early performance in Houdini’s career and contributed to his eventual fame.

Steam-Powered Popcorn Cart

Charles Cretors brought his revolutionary steam-powered popcorn machine to the fairgrounds, offering fresh, buttered popcorn on demand. The automated design amazed attendees, who had never seen such a spectacle. This innovation launched the modern popcorn industry and helped define American concession food forever.

unattributed, Wikimedia Commons

unattributed, Wikimedia Commons

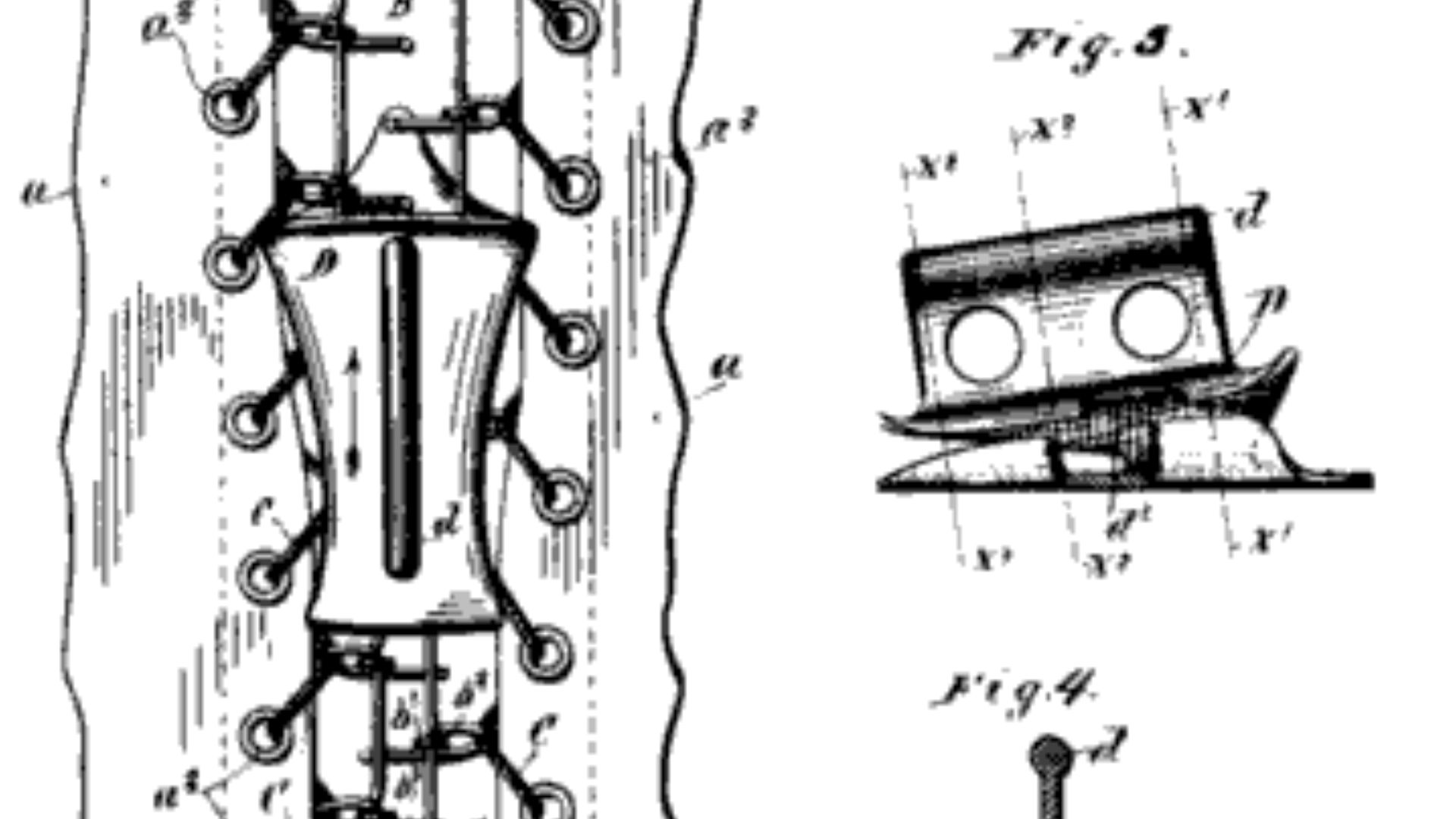

“Clasp Locker” (Zipper Prototype)

Inventor Whitcomb Judson showed his “clasp locker” at the fair—a precursor to today’s zipper. Though clunky and commercially unsuccessful at first, it fascinated fairgoers with its mechanical simplicity. Judson’s demonstration marked a quiet yet pivotal moment in garment fastening, paving the way for widespread use decades later.

United States Patent Office, Wikimedia Commons

United States Patent Office, Wikimedia Commons

Pledge Of Allegiance

During the fair’s National Public School Celebration, thousands of students across America recited the Pledge of Allegiance in unison. Written just a year earlier, it marked the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ landing. The event cemented the pledge as a patriotic ritual, eventually becoming a daily fixture in American classrooms.

Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864-1952) photographer, Wikimedia Commons

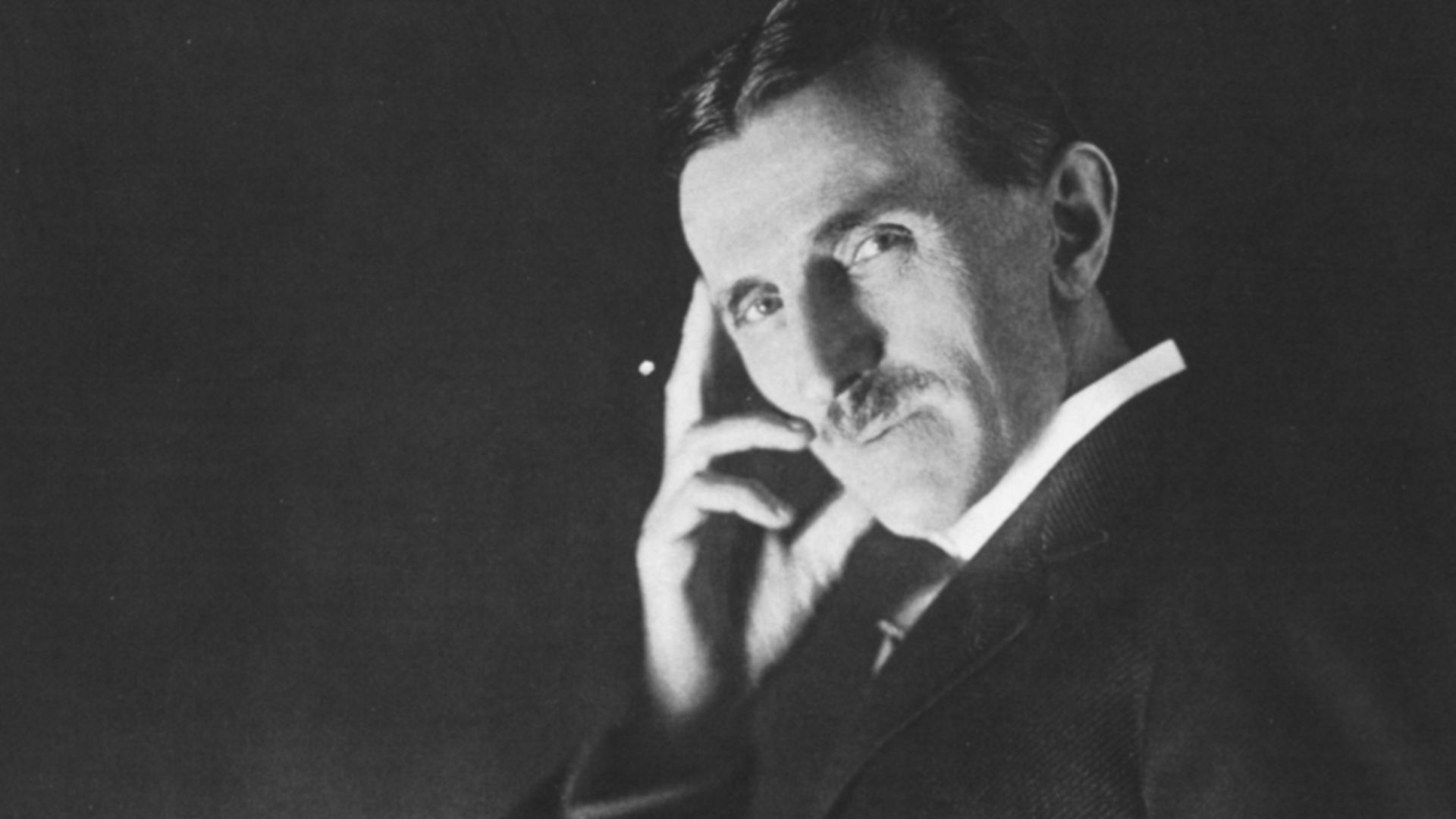

Full-Scale Public Electric Lighting

The dazzling White City glowed each night thanks to Westinghouse’s alternating current system, developed with Nikola Tesla. Lighting over 100,000 lamps, it marked the world’s first large-scale public use of electric lighting. This triumph over Edison’s direct current underscored a turning point in America’s energy future—and in global electrification.

Napoleon Sarony, Wikimedia Commons

Napoleon Sarony, Wikimedia Commons

Columbian Half‑Dollar And Quarter‑Dollar

For the first time in history, the US Mint issued coins specifically to mark a national event. The Columbian half-dollar and quarter-dollar featured Christopher Columbus and Queen Isabella, respectively. Sold at a premium, they symbolized the fair’s grandeur while introducing Americans to numismatic souvenirs in a tradition that continues with commemorative coins today.

Charles Barber, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Barber, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

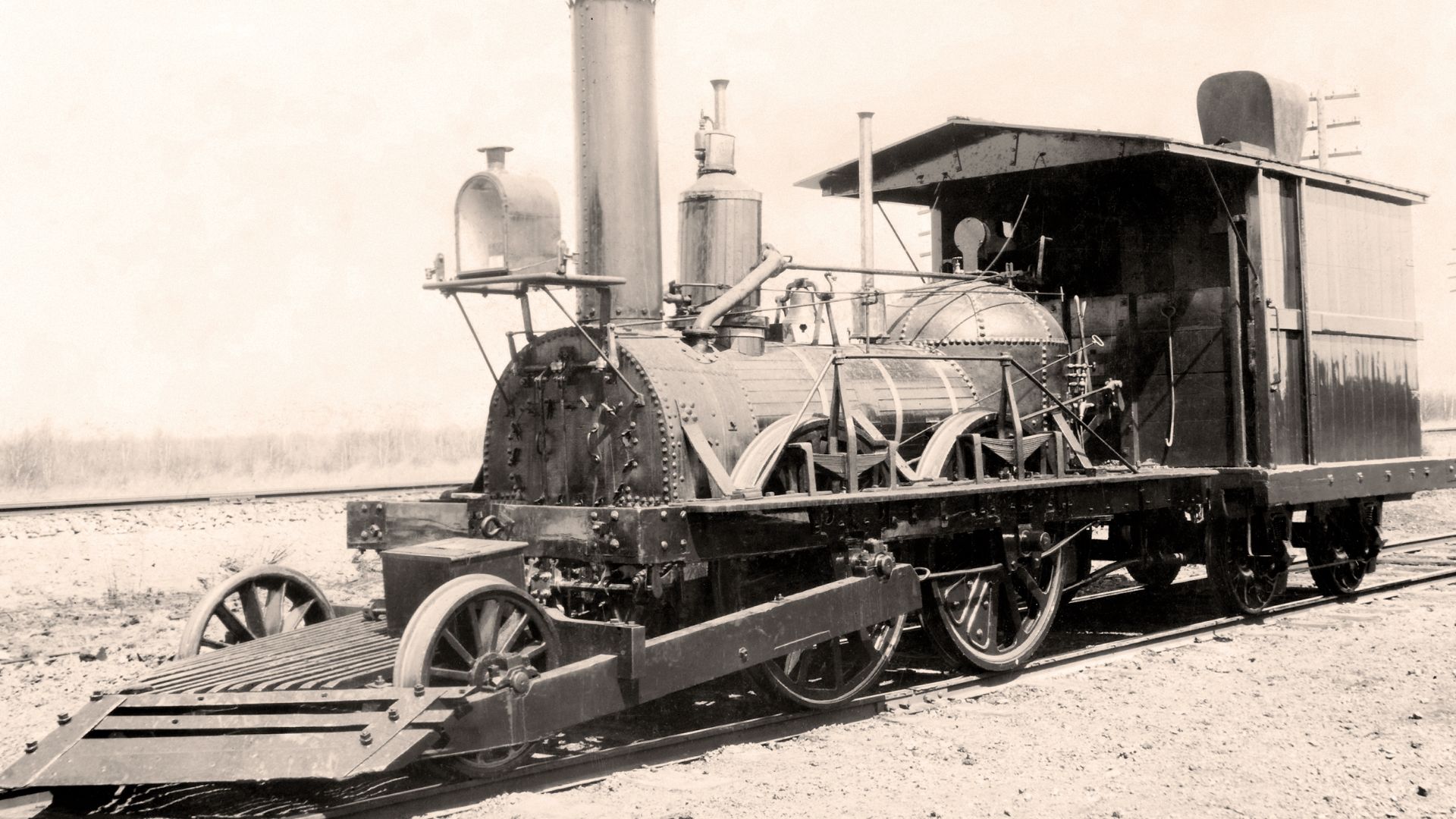

Baldwin 2‑4‑2 Locomotive, Later Called “Columbia”

Designed specifically for the fair, the Baldwin 2‑4‑2 locomotive demonstrated advancements in steam rail technology. Later dubbed “Columbia,” it introduced the 2‑4‑2 wheel arrangement that would influence future locomotive design. Operating on exhibition tracks, it symbolized the intersection of industrial progress and public fascination with modern transportation.

Parliament Of The World’s Religions

Held within the Art Institute during the fair, the Parliament of the World’s Religions brought together representatives from Eastern and Western faiths—an unprecedented interfaith dialogue. The guests included Buddhists, Hindus, Christians, Muslims, and others, promoting mutual understanding and launching a global conversation about religious pluralism that continues today.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Hand-Powered Dishwasher

Josephine Cochrane’s innovative dishwasher stunned attendees inside the Machinery Hall. Frustrated by chipped heirloom china, she invented a hand-powered machine using water pressure instead of brushes. Her elegant solution to a domestic problem won awards and admiration, especially from hotels. It led to the birth of the commercial dishwasher industry.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Moving Sidewalk

The moving sidewalk debuted as a futuristic feature of the fair's pier extension. Passengers rode effortlessly while taking in views of Lake Michigan. Though modest in length, it captured the public’s imagination as a novel transportation concept. It would later appear in airports and global exhibitions.

First Columbus Day School Ceremony

October 12, 1892, marked a landmark in US civic culture. As part of the exposition’s commemorative events, public schools nationwide observed the first organized Columbus Day ceremony. This synchronized celebration fostered national identity and reinforced the role of education in shaping civic rituals—many of which persist to this day.

Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Wikimedia Commons

Ridolfo del Ghirlandaio, Wikimedia Commons

Helen Keller And Susan B Anthony

The Woman’s Building hosted a parallel Congress where pioneering figures like Susan B Anthony and a young Helen Keller were present. Anthony advocated fiercely for women’s rights, while Keller's presence symbolized educational reform. These moments offered attendees compelling visions of progress toward gender equity and social inclusion.

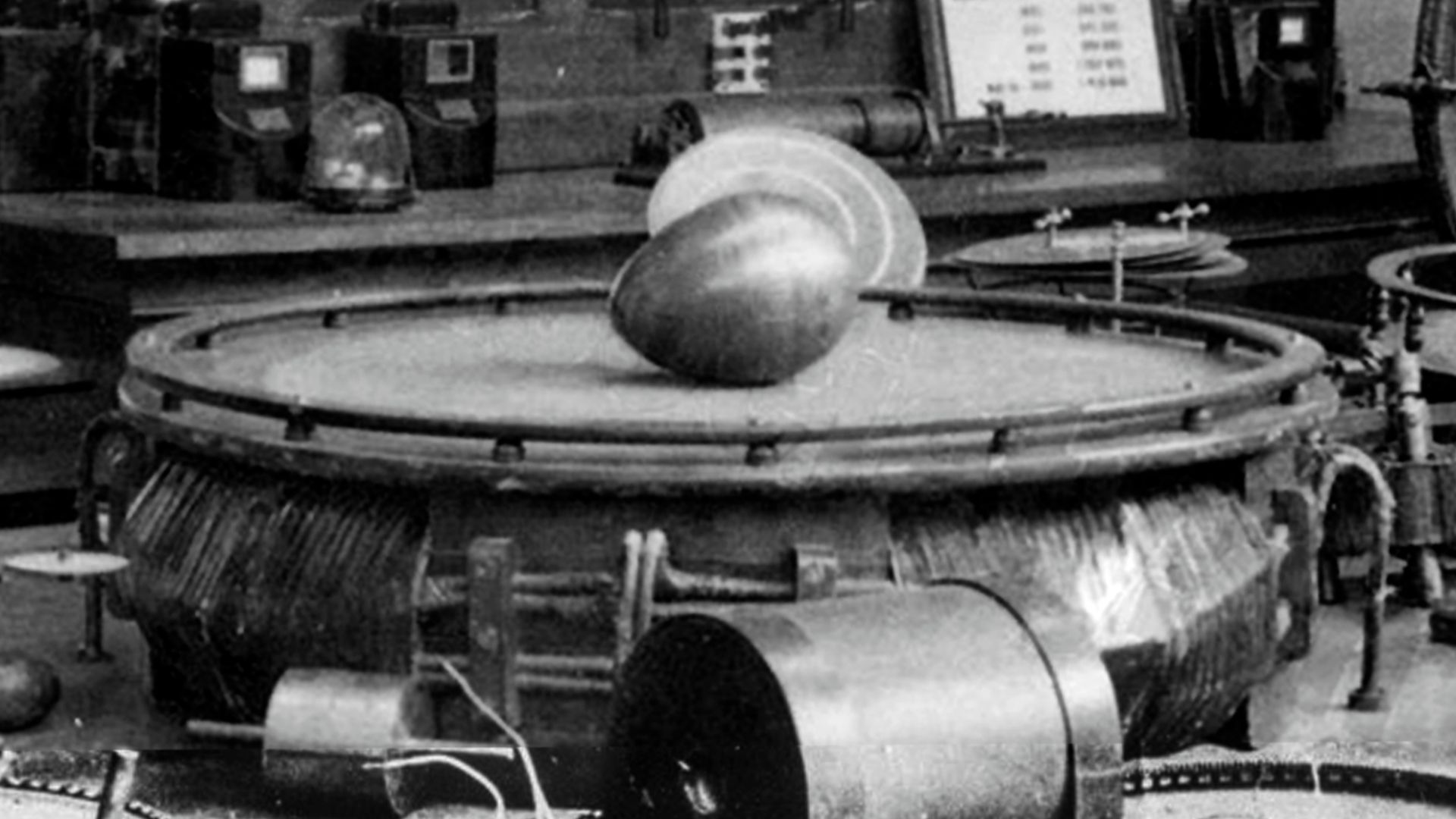

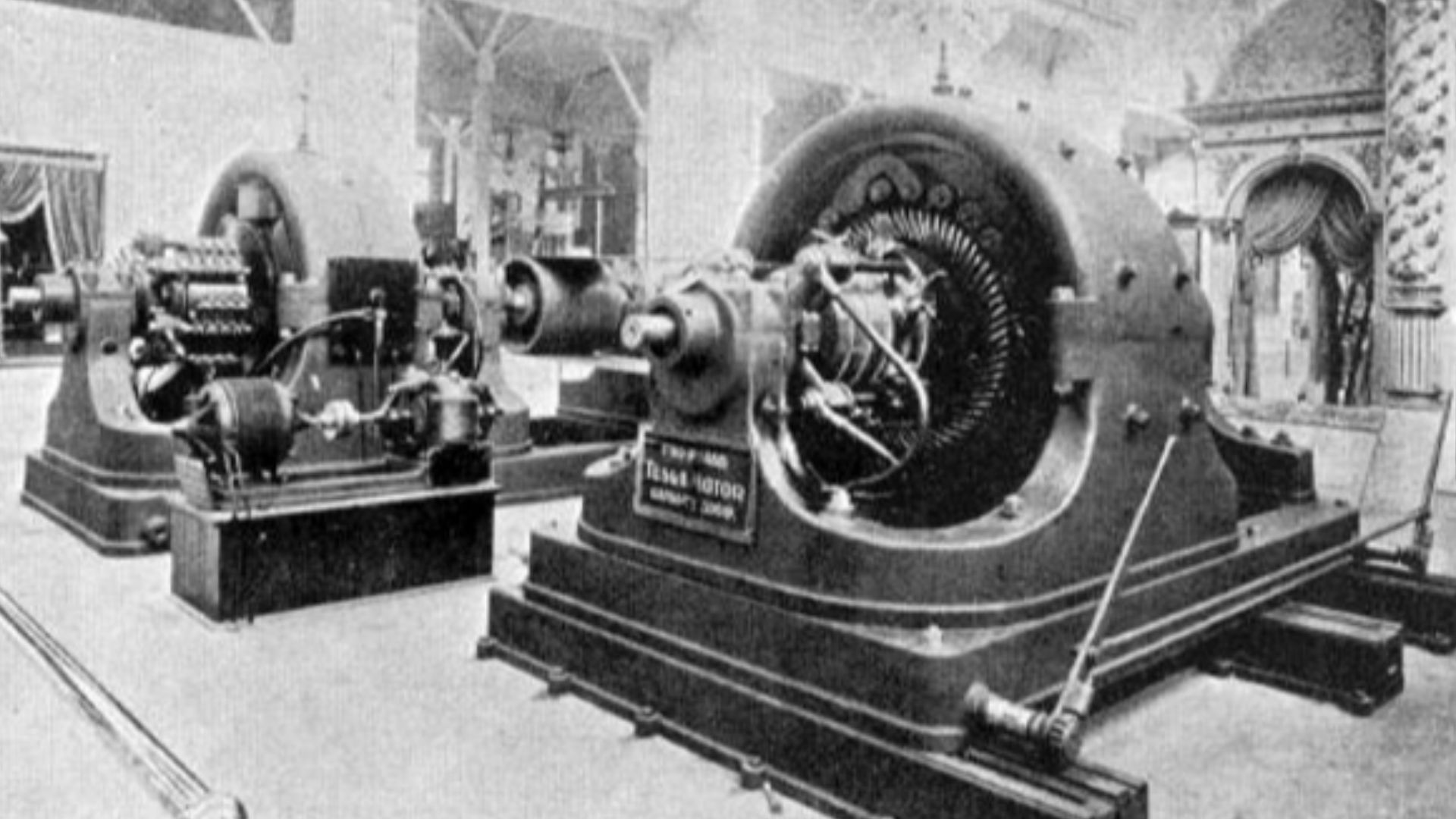

Tesla’s Egg Of Columbus

Among the fair’s most compelling scientific displays, Tesla’s “Egg of Columbus” used a rotating magnetic field to spin a copper egg positioned upright. This elegantly visualized the principle of induction motors. The demonstration clarified how the alternating current worked and offered a tangible glimpse into the future of electricity.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Frederick Jackson Turner’s Frontier Thesis

Historian Frederick Jackson Turner chose the fair’s affiliated academic conference to discuss his now-famous “Frontier Thesis”. Arguing that the American frontier had shaped national character, his lecture reframed how historians viewed US development. Though controversial, it profoundly influenced historical scholarship and national identity well into the twentieth century.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

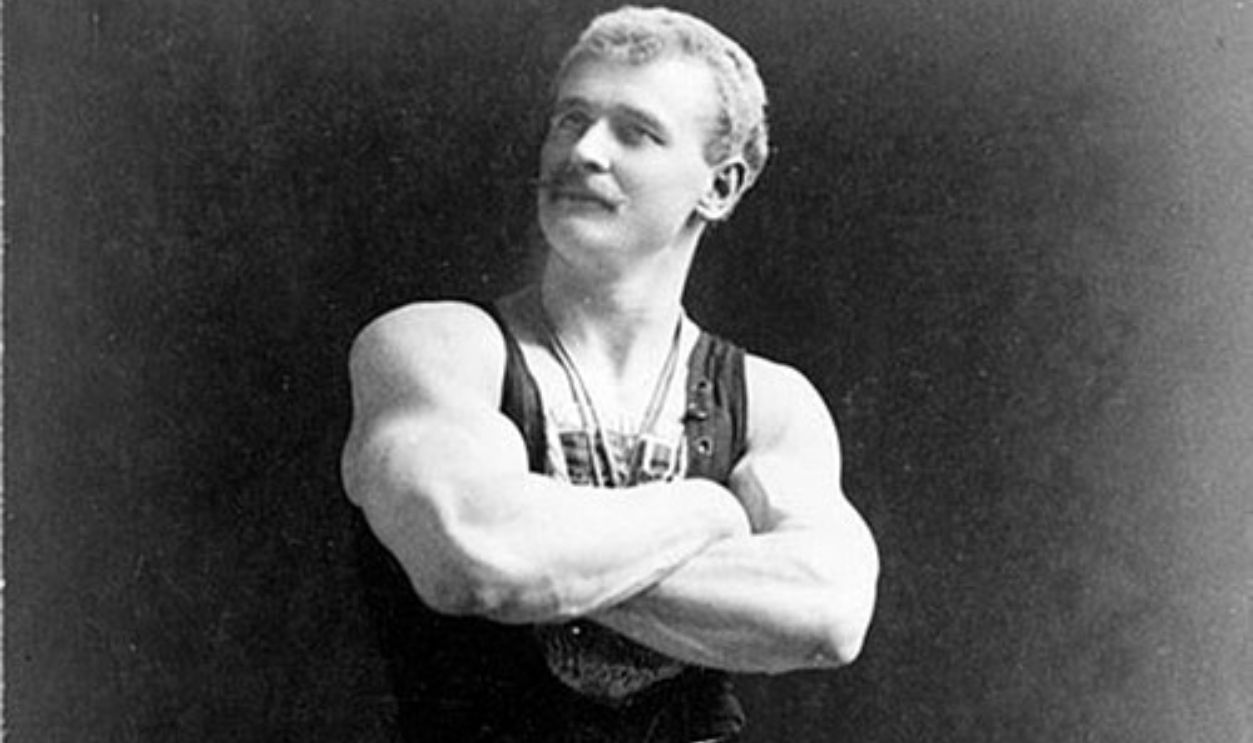

Bodybuilder Eugen Sandow

Often considered the father of modern bodybuilding, Eugen Sandow performed daily at the fair. Audiences marveled at his muscular physique and controlled strength, which he presented more as performance art than brute display. His appearances helped legitimize physical culture and laid the foundation for modern fitness industries.

Benjamin J. Falk, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin J. Falk, Wikimedia Commons

Cream Of Wheat

Cream of Wheat quietly debuted at the fair, promoted by millers from Grand Forks, North Dakota. Its smooth texture and warm simplicity appealed to a wide audience. While not flashy, this nourishing breakfast food resonated with health-conscious visitors and soon became a comforting staple across American households for generations.

“Street In Cairo” And Belly-Dance

The Midway’s “Street in Cairo” exhibit transported fairgoers to a stylized Egyptian bazaar. Amid colorful textiles and exoticized scenery, a performer known as “Little Egypt” introduced belly dance to American audiences. The performance was sensational and provocative. It marked a cultural moment that influenced entertainment and public fascination with the “Orient”.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Aunt Jemima Pancake Mix

Nancy Green, a formerly enslaved woman, brought the Aunt Jemima character to life at the exposition and dazzled fairgoers with live cooking and storytelling. Her role helped launch one of the most successful pre-mixed pancake brands in US history while also embedding complex cultural legacies into American food advertising.

A. B. Frost, Wikimedia Commons

A. B. Frost, Wikimedia Commons

Elongated Coins

A novel souvenir emerged at the fair: the elongated coin. By pressing pennies through a roller die, visitors could imprint custom designs celebrating their visit. These affordable keepsakes became wildly popular and led to the birth of a unique niche in numismatics. This tradition is still found in amusement parks and historic sites today.

J. Van Meter (talk), Wikimedia Commons

J. Van Meter (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Brownie Dessert

Chicago socialite Bertha Palmer asked her chefs to create a portable dessert for boxed lunches at the Women’s Pavilion. What emerged was the first documented brownie—dense, rich, delicious, and ideal for eating by hand. This elegant invention quickly gained traction, later becoming a beloved and unmistakably American dessert classic.

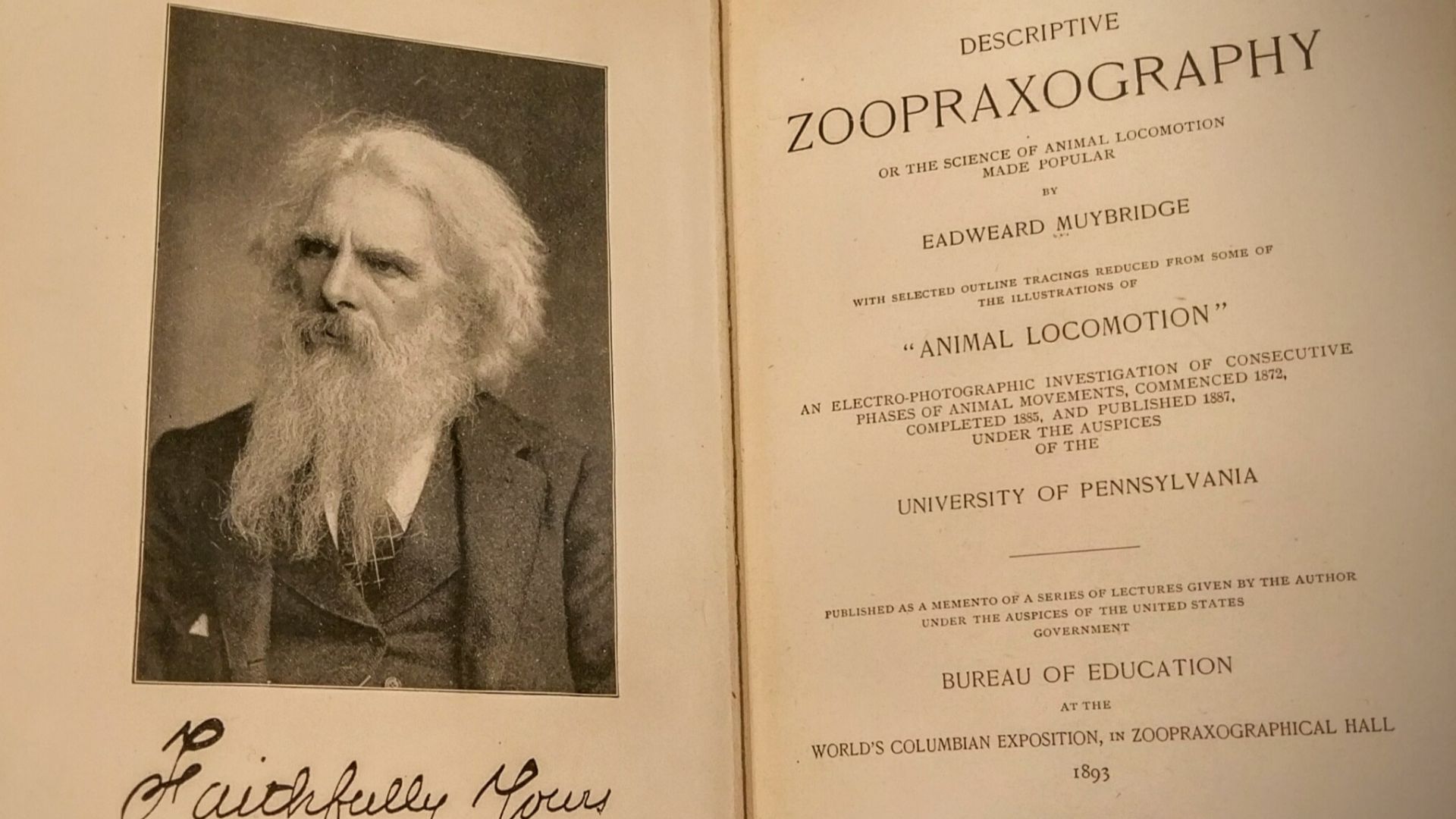

Zoopraxographical Hall

Photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s Zoopraxographical Hall screened moving images using a spinning disc and light projection. These sequences of galloping horses and human motion offered fairgoers a glimpse into motion photography. The exhibit predated commercial cinema and laid essential groundwork for film and animation.

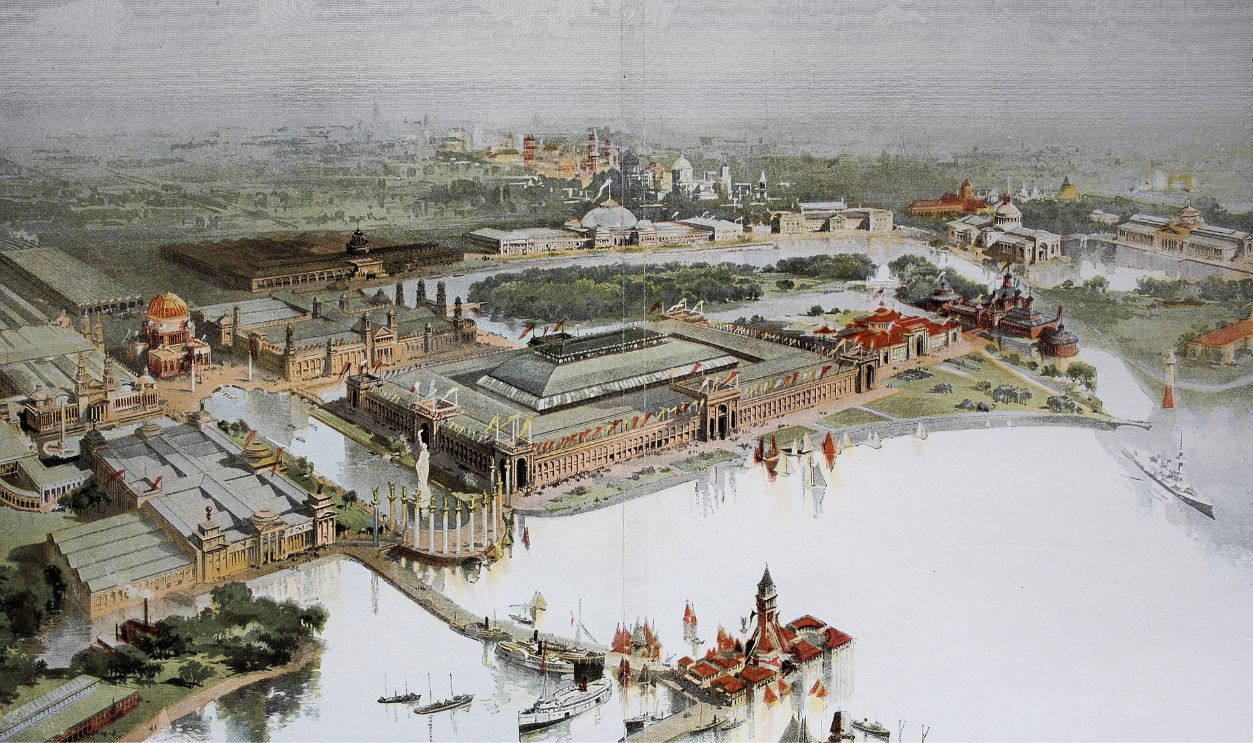

“White City” Neoclassical Buildings

Led by architect Daniel Burnham, the fair’s main buildings embraced neoclassical symmetry and white stucco facades. This dazzling ensemble became known as the “White City.” Beyond its aesthetic impact, it influenced urban planning nationwide. It also inspired the City Beautiful movement and shaped American civic architecture for decades to follow.

Nichols, H. D., 1859-1939 (artist); L. Prang & Co. (publisher), Wikimedia Commons

Nichols, H. D., 1859-1939 (artist); L. Prang & Co. (publisher), Wikimedia Commons

Milton Hershey’s Chocolate Equipment

Milton Hershey attended the fair not as a confectioner but as an observer. However, the newest chocolate-making machinery on display changed his future. Inspired by its efficiency and flavor potential, he soon pivoted from caramel to cocoa and launched what would become one of the largest chocolate empires in the world.

unknown (original image); Centpacrr (derivative image), Wikimedia Commons

unknown (original image); Centpacrr (derivative image), Wikimedia Commons

Peanut Butter

Among the many innovations in the food halls, peanut butter stood out as a plant-based protein source. Promoted as a digestible food for people who couldn’t chew meat, it intrigued progressive nutritionists. Though still far from the sweetened spreads of today, its fair appearance helped begin its long rise to popularity.

PiccoloNamek at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

PiccoloNamek at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Venetian-Style Lagoons And Gondolas

Frederick Law Olmsted, co-designer of Central Park, envisioned flowing canals and lagoons as part of the fair’s immersive environment. Gondolas drifted beneath arched bridges and offered tranquil rides between exhibition halls. These water features blended European charm with American showmanship and added elegance and spatial cohesion to the White City’s grandeur.

Vienna Sausage (Vienna Beef)

Vienna Beef began its American journey at a small stand near the fair’s Midway Plaisance. Run by Austrian-Hungarian immigrants, the sausage stand quickly drew crowds with its flavorful frankfurters. The success sparked the founding of Vienna Beef in Chicago—a company still serving up hot dogs more than a century later.

Staff-Coated Buildings

To meet tight deadlines and budgets, most exposition buildings were constructed with “staff,” a mix of plaster, cement, and jute. Painted to mimic marble, these facades gleamed white but were temporary. The material enabled architectural experimentation on a grand scale and gave the fair its opulent look without permanent infrastructure.

C.D. Arnold, WCE official photographer., Wikimedia Commons

C.D. Arnold, WCE official photographer., Wikimedia Commons

Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer

Competing against international brewers, Pabst’s lager likely earned a medal at the fair—an honor that reinforced its ‘Blue Ribbon’ branding, which had been used since 1882. The award boosted national recognition. It established Pabst as a symbol of quality American brewing by linking the beer permanently to the prestige of the exposition.

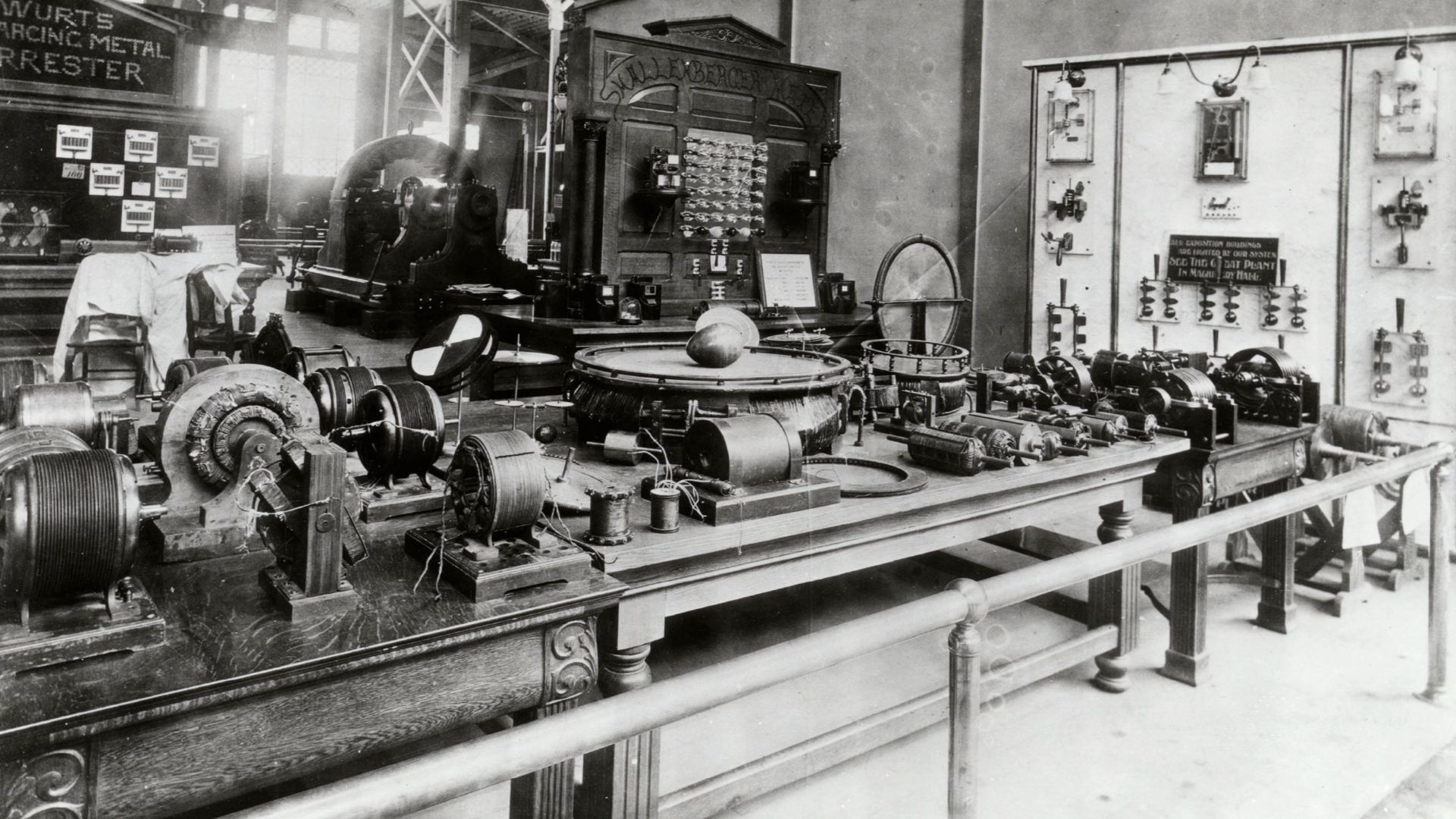

Electric Induction Motors And Rotating-Field Demos

Visitors stepping into the Electricity Building encountered functional induction motors powered by Tesla’s AC system. They ran continuously and proved alternating current’s practicality. As a cornerstone of the fair’s technical narrative, they helped shift public opinion in favor of AC during the height of the electrical debate.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Phosphorescent Lamps

Glowing softly in dim corners of the Electricity Building, phosphorescent lamps captured attention with their ethereal light. These chemically coated bulbs absorbed energy and re-emitted it slowly. As a result, they offered a preview of experimental lighting beyond incandescence. Their ghostly afterglow hinted at novelty and promise in future illumination technologies.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

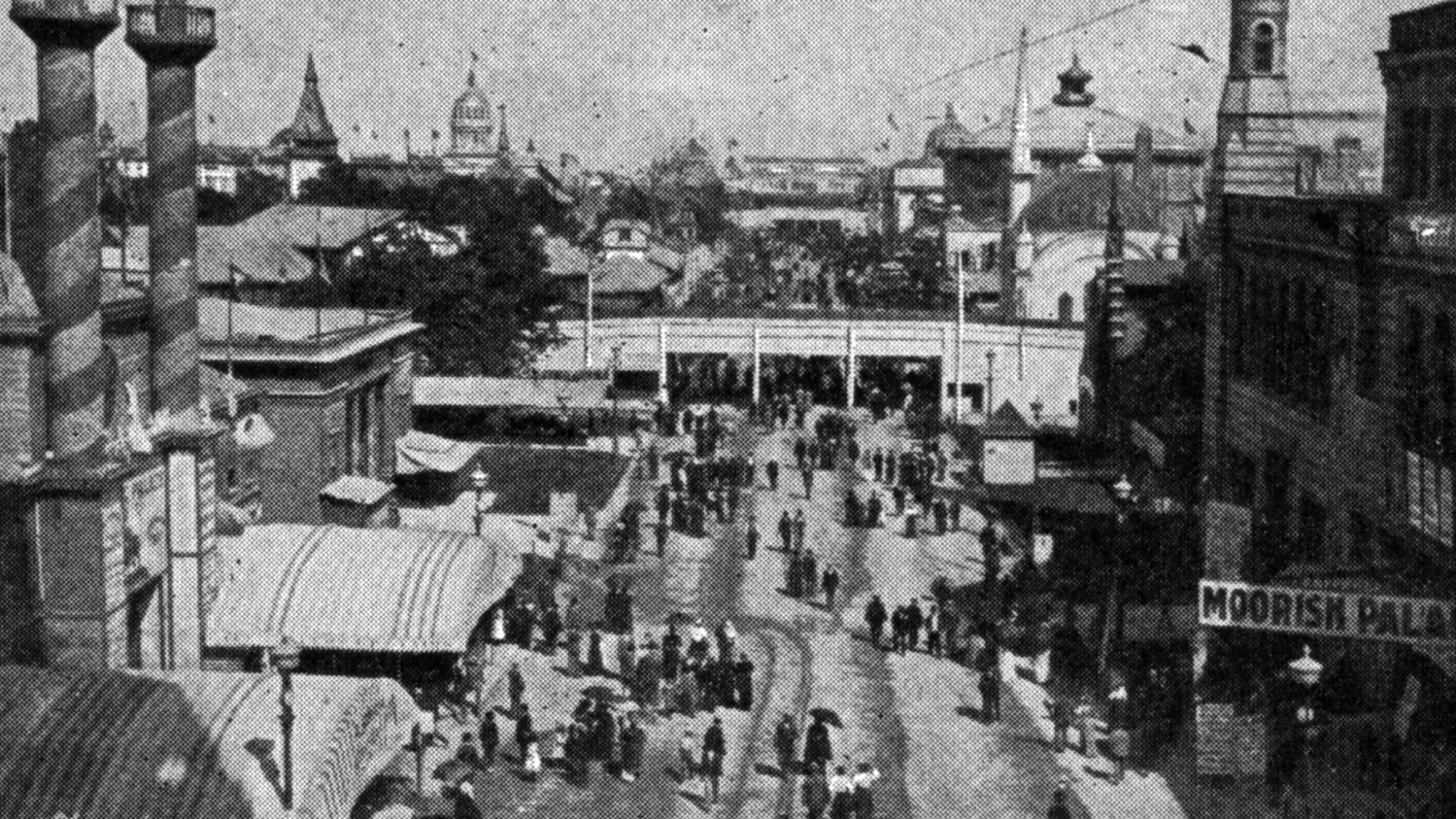

Midway Plaisance

Stretching nearly a mile, the Midway Plaisance was Olmsted’s answer to entertainment and cultural diversity. It featured international pavilions and amusements. This vibrant stretch connected education and spectacle. It set the blueprint for future world fairs and even influenced the modern concept of theme parks and expositions.

E. Benjamin Andrews, Wikimedia Commons

E. Benjamin Andrews, Wikimedia Commons

Electric Automobile Prototype

William Morrison’s electric carriage was rechargeable and unlike anything else at the fair. It offered a rare look at automotive innovation. Though its top speed barely reached 14 miles per hour, its silent operation impressed visitors. He introduced the idea of clean, battery-powered transportation decades before electric cars became a mainstream concept.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Cracker Jack

A simple twist on popcorn became a sensation when Cracker Jack premiered at the fair. Coated in molasses and tossed with peanuts, the mix stood out from traditional snacks. Its rich flavor and catchy name laid the groundwork for one of America’s longest-lasting and most iconic treat brands.

Lindsey Turner, Wikimedia Commons

Lindsey Turner, Wikimedia Commons

Anthropology Building And Ethnographic Displays

Inside the Anthropology Building, curated exhibits showcased Native American and Indigenous Arctic cultures. While presented through a 19th-century colonial lens, the displays included tools and live demonstrations. For many attendees, it was their first exposure to Indigenous life, and for anthropologists, it was an unprecedented attempt to catalog human diversity.

C. D. Arnold (1844-1927); H. D. Higinbotham, Wikimedia Commons

C. D. Arnold (1844-1927); H. D. Higinbotham, Wikimedia Commons

Juicy Fruit Gum

Juicy Fruit offered a new flavor and introduced a modern way of marketing. Wrigley gave away samples at the fair, which created instant brand buzz. The gum’s tropical taste and convenient size helped it catch on fast and made it one of the earliest examples of a successful product sampling strategy.

istolethetv, Wikimedia Commons

istolethetv, Wikimedia Commons

Live Orchestras And Concerts

Throughout the exposition, live orchestras performed classical and contemporary compositions in major halls like the Music Hall and the Agricultural Building. These concerts highlighted the cultural tone of the fair, exposing visitors from across the country to sophisticated musical traditions and reinforcing the fair’s role as a center of art and intellect.

JW Taylor,, photographer., Wikimedia Commons

JW Taylor,, photographer., Wikimedia Commons

Shredded Wheat Cereal

Health reformers and curious attendees took note of Henry Perky’s shredded wheat at the exposition. Unlike sugary fare, this baked cereal aimed to offer nutrition and convenience. Its unusual texture and shape sparked conversation. Soon, it moved from novelty to breakfast staple as America embraced ready-to-eat cereals.

Pete unseth, Wikimedia Commons

Pete unseth, Wikimedia Commons

Viking Ship From Norway

Sailing 3,000 miles from Bergen to Chicago, a full-scale Viking longship replica honored Leif Erikson’s early explorations. Modeled on the 9th-century Gokstad ship, it docked beside the fairgrounds, stunning visitors with its design and journey. The ship highlighted Norse heritage and added a mythic, historical layer to the exposition.

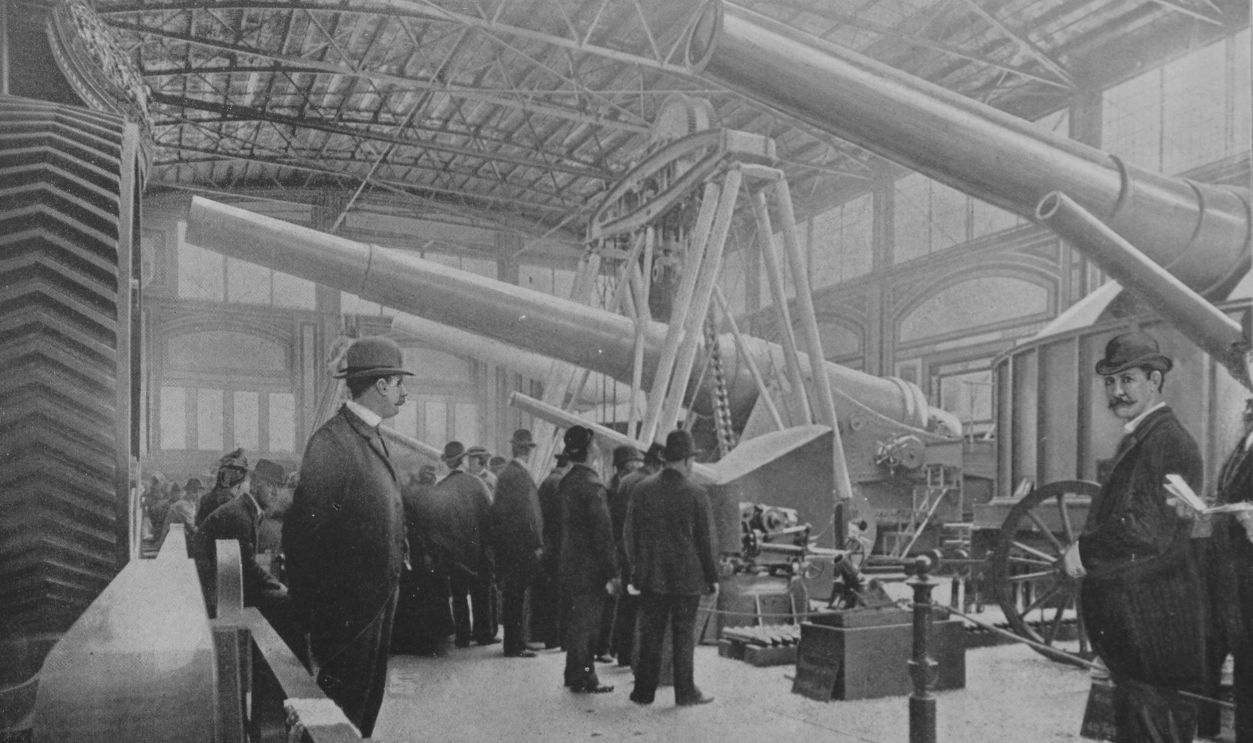

Krupp Artillery Pavilion

Germany’s Krupp Works erected a pavilion filled with the latest military technology, including a 42-ton coastal gun. Visitors were awed—and sometimes unnerved—by the scale and power of the weapons. The exhibit underscored the era’s industrial might and foreshadowed the coming importance of military hardware in geopolitics.

Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Getty Images

Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, Getty Images

John Bull Locomotive

The John Bull, America’s oldest functioning steam locomotive, was fully restored and operating at the fair. Originally built in 1831, it symbolized a century of railway progress. Visitors could watch it in motion, and it offered a vivid link between the country’s early transportation history and its modern industrial achievements.

Fireworks Displays

Each evening, brilliant fireworks illuminated the fairgrounds, lighting the night sky above the White City. These displays showcased pyrotechnic innovation and theatrical timing. With synchronized music and water effects, the nightly spectacles drew crowds and capped off the fair’s daily blend of wonder and entertainment.

Bildagentur-online, Getty Images

Bildagentur-online, Getty Images

Naval Battle Reenactments

One of the fair’s more theatrical attractions involved simulated naval battles in the South Lagoon. Using scaled vessels and choreographed maneuvers, the reenactments brought maritime combat to life. Though primarily for the show, they also reflected the growing public interest in naval strength and global military dynamics.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons