Threads That Refuse To Disappear

One person says an invention or concept is the “first of its kind”. Another argues, with proof, that ancient civilizations did it long before. These relics belong to that quiet chorus of “we were here first”.

Antikythera Mechanism

When divers pulled up corroded bronze gears from a shipwreck in 1901, nobody expected it to be an ancient computer. Originating back to around 100 BCE, the Antikythera Mechanism calculated planetary motions and calendars with jaw-dropping precision.

Nebra Sky Disk

Discovered in Germany, this Bronze Age disk stunned archaeologists with golden symbols of the sun, moon, and stars. At approximately 3,600 years old, it represents some of the earliest known astronomical knowledge in Europe, far surpassing what scholars previously thought possible.

Frank Vincentz, Wikimedia Commons

Frank Vincentz, Wikimedia Commons

Baghdad Battery Jars

Simple clay jars with copper and iron fittings from Parthian Iraq sparked wild speculation. Some claimed they were batteries, though most experts now think they held scrolls or ritual liquids. Whatever their use, their design feels oddly modern for the time.

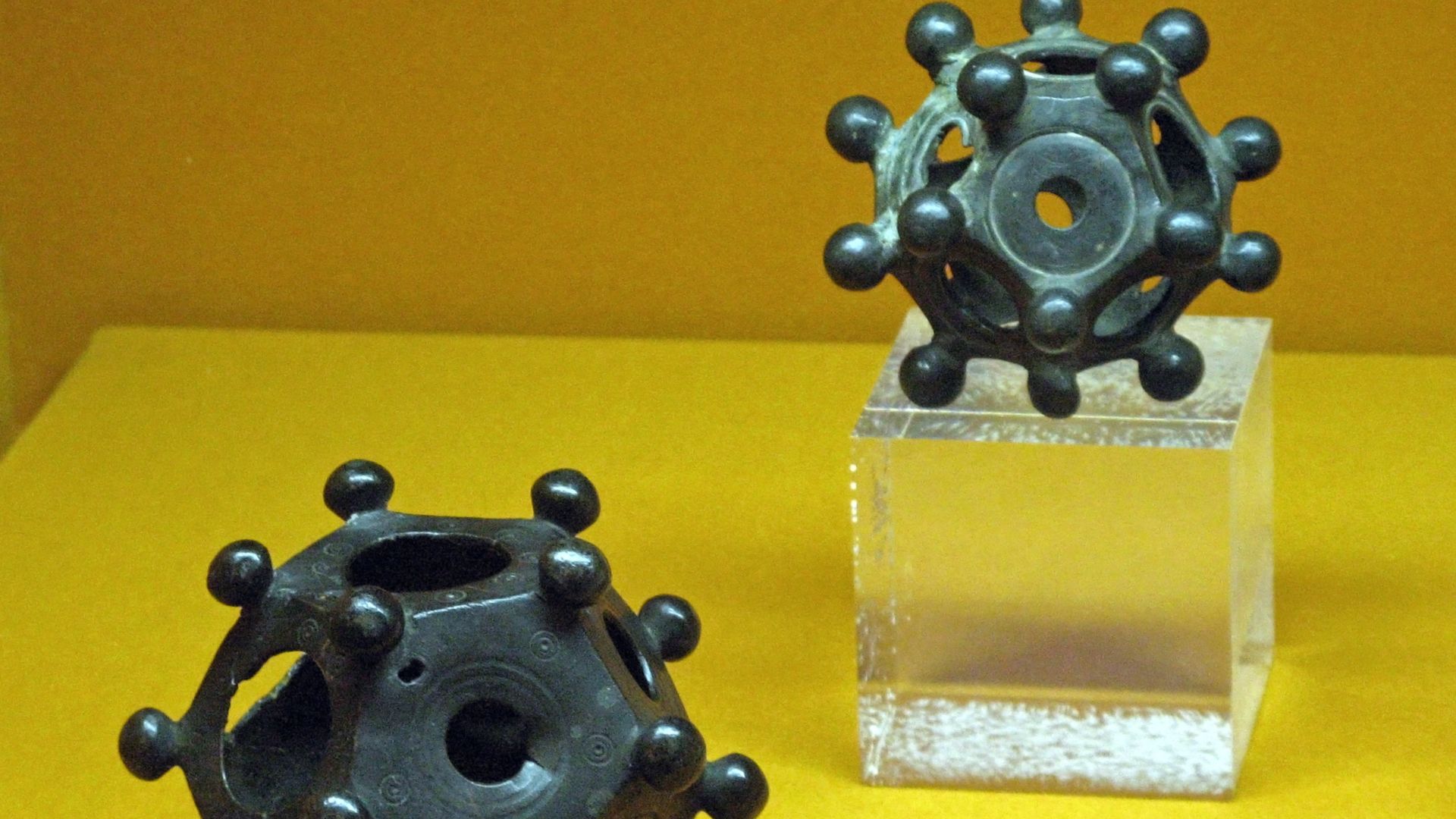

Roman Dodecahedra

Small bronze dodecahedra with holes on each face have been found across Europe. No ancient texts mention them, leaving their function a mystery. Some suggest candlesticks or tools for measuring. Their existence keeps scholars guessing, which only adds to their intrigue.

Mark Landon, Wikimedia Commons

Mark Landon, Wikimedia Commons

Lycurgus Cup

This Roman glass goblet changes color depending on light—green from one angle, red from another. The effect comes from nanoparticles embedded in the glass. It shows how artisans mastered materials science in ways that modern researchers only recently rediscovered.

Damascus And Wootz Steel Blades

Medieval travelers marveled at blades from India and the Middle East, patterned like flowing water. Made from crucible steel known as wootz, they combined strength and flexibility unmatched for centuries. The technique was so advanced that it disappeared before industrial metallurgy revived it.

Delhi Iron Pillar

This six-ton iron column in Delhi has resisted rust for 1,600 years. Ancient Indian blacksmiths created a remarkably pure iron that forms a protective layer instead of corroding. Modern metallurgists still study it to understand how early ironworkers achieved such resilience.

Greek Fire

Byzantine navies terrified enemies with Greek Fire, a liquid that continued burning even on water. Delivered through pressurized siphons, it was so effective that the formula remained a closely guarded state secret. Its sudden appearance in history feels like a leap forward.

Heron’s Aeolipile

In Roman Egypt, Heron of Alexandria built a steam-powered sphere that spun when heated. Known as the aeolipile, it was more demonstration than engine, yet it reveals how close ancient inventors came to harnessing steam power long before the Industrial Revolution.

Zhang Heng’s Seismoscope

In 132 CE, the Chinese polymath Zhang Heng created a bronze vessel that detected distant earthquakes. A mechanism inside dropped balls shows the direction of tremors. This ingenious invention predates Western seismology by more than 1,500 years.

Thank you for visiting my page from Canada, Wikimedia Commons

Thank you for visiting my page from Canada, Wikimedia Commons

Minoan Plumbing At Knossos

The palaces of Knossos in Crete featured terracotta pipes and gravity-fed latrine systems more than 3,500 years ago. Using water from cisterns or aqueducts, they created sanitation far ahead of their time, long before most of Europe adopted similar comforts.

Phaistos Disk

This small clay disk from Crete, stamped with spiraling pictographs, remains one of archaeology’s most puzzling finds. Dating to around 1700 BCE, its symbols were impressed with stamps, suggesting a form of movable type. However, no other similar stamped texts have ever been discovered.

Gobekli Tepe Pillars

High on a Turkish hill, massive T-shaped pillars covered in animal carvings were erected around 9600 BCE. That’s thousands of years before cities or pottery. Their scale point to a complex social organization much earlier than historians had presumed.

Jericho Stone Tower

At nearly 30 feet tall, the stone tower in ancient Jericho dates back over 9,000 years. Its construction required planning, labor, and engineering, which was unexpected for the time. As one of the oldest known monuments, it challenges assumptions about early architecture.

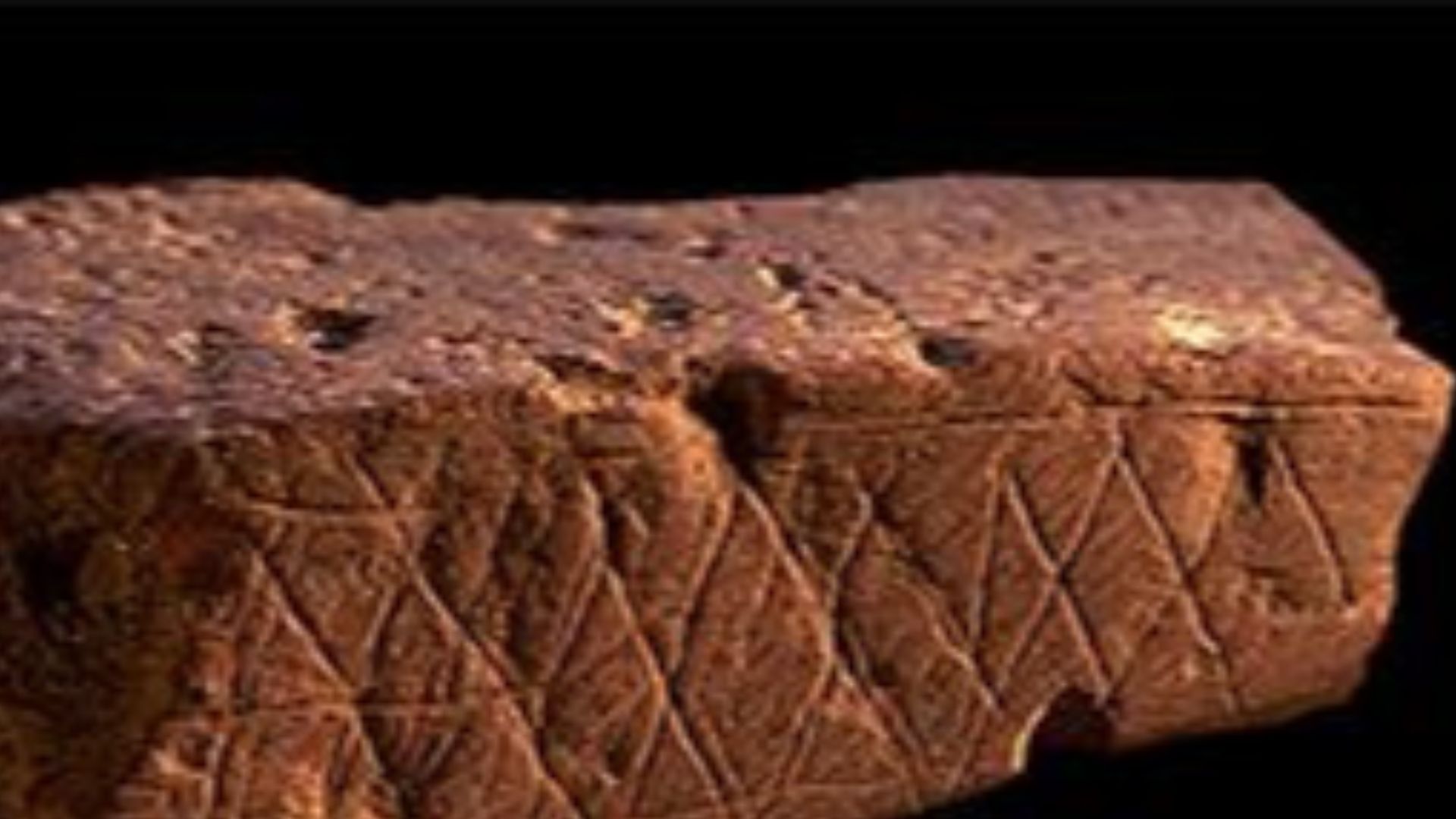

Blombos Engraved Ochres

In a South African cave, archaeologists found 75,000-year-old pieces of ochre etched with cross-hatched designs; some of the earliest examples of such symbolic expression. They push back the timeline for when humans developed abstract thought and complex cultural behavior.

Chris S. Henshilwood, Wikimedia Commons

Chris S. Henshilwood, Wikimedia Commons

Denisova Bracelet

From a Siberian cave came a 65,000-year-old polished stone bracelet, drilled with astonishing precision. Likely made by Denisovans, an extinct hominin group, it demonstrates tool use and artistry on a level once thought exclusive to much later human cultures.

Denisova Cave bracelet by The Siberian Times

Denisova Cave bracelet by The Siberian Times

Viking Sunstone

Icelandic sagas mention magical stones guiding sailors through fog. Archaeologists now link this to Iceland spar crystals, which can polarize light and reveal the sun’s position. If Vikings used them, it means they applied optical science long before it was formally understood.

Dr. Bernd Gross, Wikimedia Commons

Dr. Bernd Gross, Wikimedia Commons

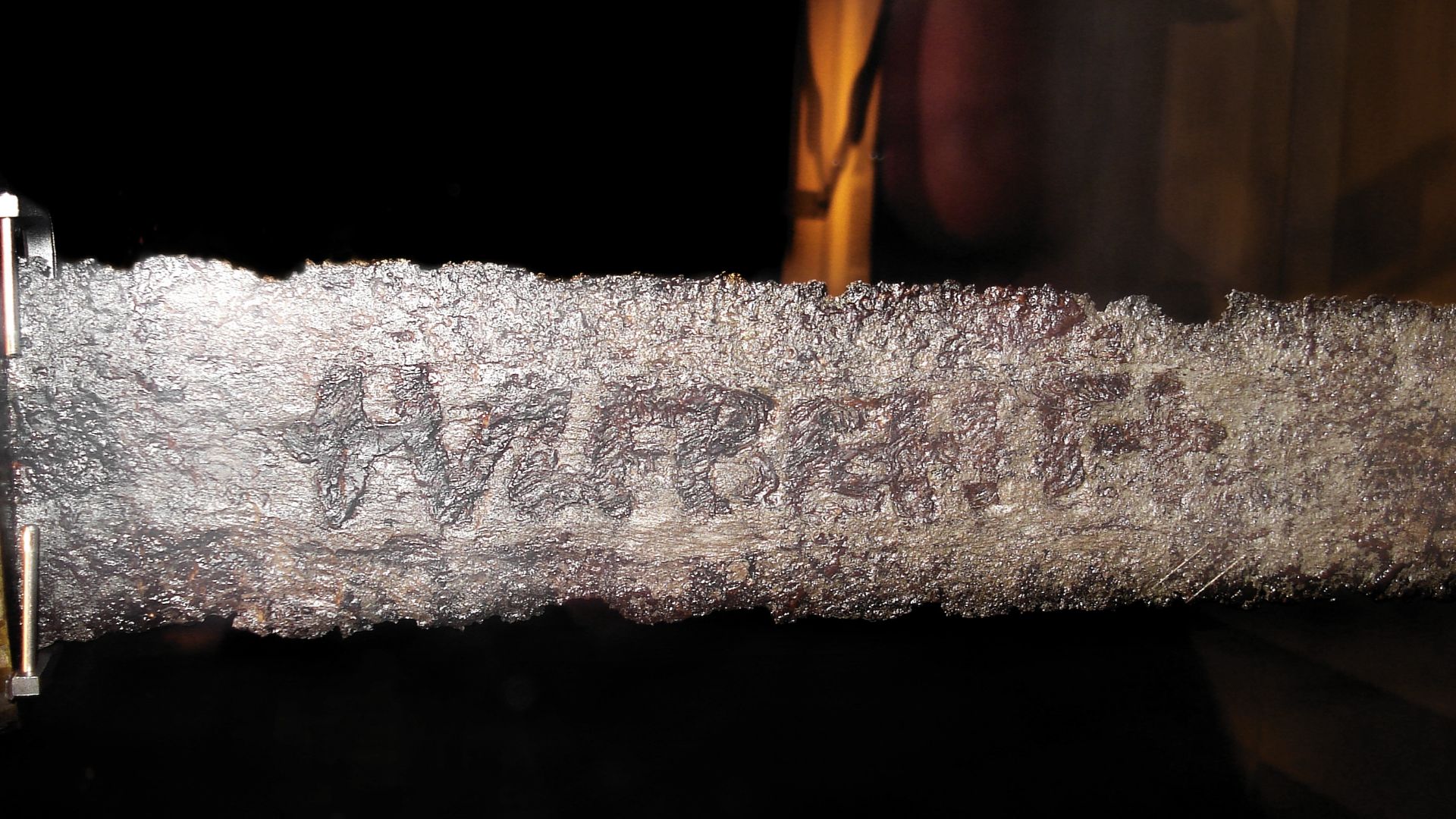

Ulfberht Swords

Medieval Europe saw some swords inscribed “+ULFBERHT+” with a purity of steel nearly matching modern standards. Likely made with imported crucible steel, they far outclassed contemporary weapons. Their mysterious production method hints at lost knowledge that was passed along through ancient trade networks.

Ulfberht.jpg: Torana derivative work: Hic et nunc, Wikimedia Commons

Ulfberht.jpg: Torana derivative work: Hic et nunc, Wikimedia Commons

Roman Concrete

Roman engineers mixed volcanic ash into their concrete to create structures that have survived earthquakes, seawater, and centuries of weather. Some Roman harbor works even grow stronger over time. Their recipe remained unmatched until modern scientists pieced together its chemistry.

Pantheon Dome

The dome of the Roman Pantheon, built nearly 2,000 years ago, is still the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome. Its perfect proportions and clever material gradation show an engineering mastery that wouldn’t reappear until much later in architectural history.

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, Wikimedia Commons

Hydraulis Water Organ

Unearthed in Greece, the hydraulis was the world’s first keyboard instrument, using water pressure to push air through pipes. Dating to the third century BCE, it demonstrates how Hellenistic engineers blended science, mechanics, and music in ways that feel surprisingly modern.

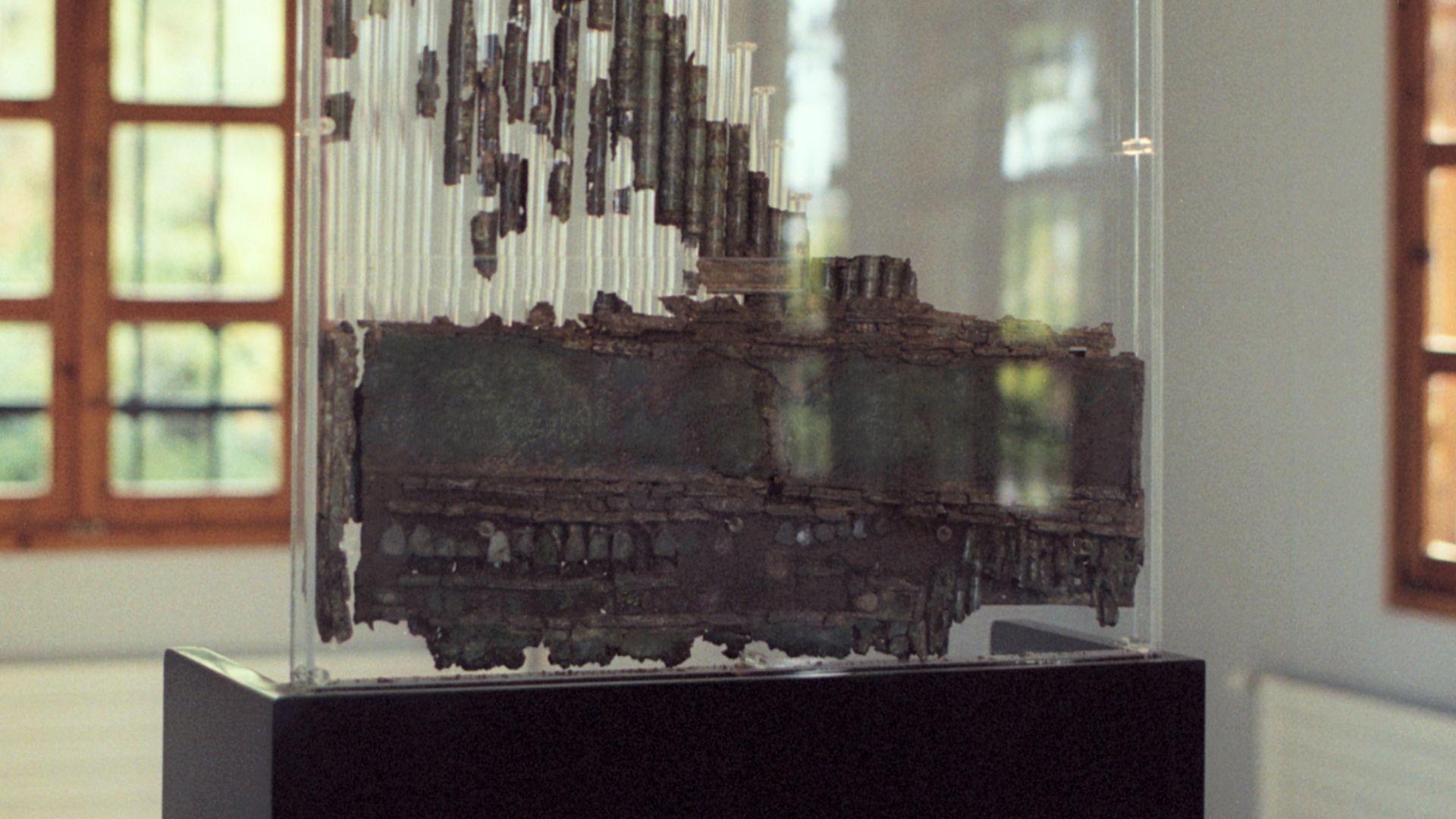

Nemi Ship Fittings

Caligula’s enormous pleasure ships, raised from Lake Nemi in the 20th century, revealed marble floors and plumbing systems. Their sophistication shocked scholars, since such mechanical luxuries seemed centuries ahead of Roman engineering. Sadly, most remains were lost in WWII.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Piri Reis Map

Drawn in 1513 by Ottoman admiral Piri Reis, this map incorporates surprisingly accurate coastlines, some traced from far older charts. Although it is not evidence of lost civilizations, it demonstrates how ancient geographical knowledge was circulated across cultures long before the advent of modern cartography.

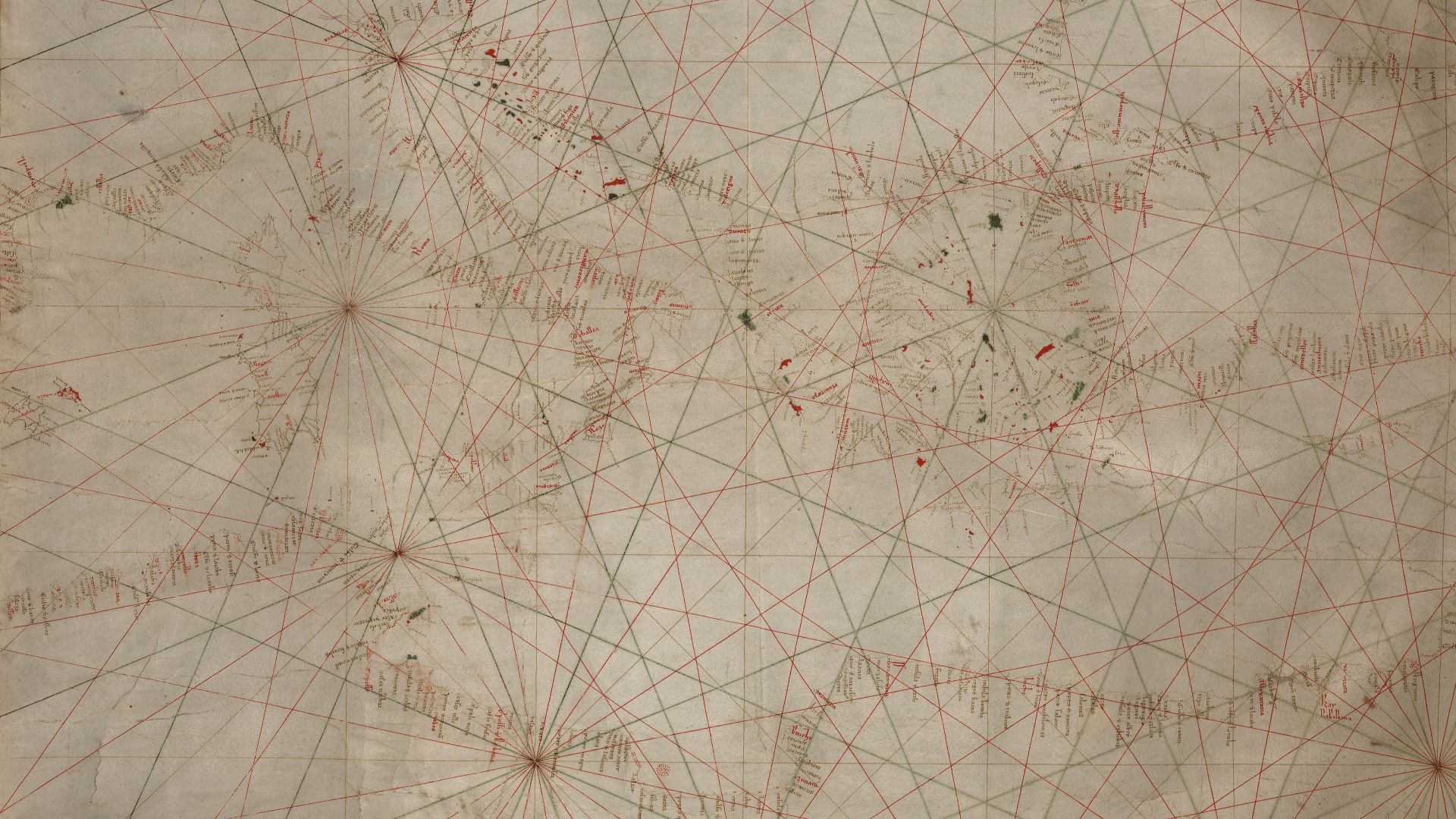

Portolan Charts

Appearing in medieval Europe around the 13th century, portolan sea charts displayed coastlines with uncanny accuracy. They predate advanced navigation tools, suggesting sailors built detailed maps through accumulated experience. Their sudden precision still puzzles historians studying the evolution of cartography.

anonymous, probably Genoan, Wikimedia Commons

anonymous, probably Genoan, Wikimedia Commons

Nazca Geoglyphs

In the Peruvian desert, vast geoglyphs of animals and lines stretch for miles. Created around 500 CE, they required large-scale planning and surveying techniques. Though best seen from above, some lines are also visible from the surrounding foothills. However, their true purpose remains debated.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Sacsayhuaman Masonry

High above Cusco, Inca engineers fitted giant stone blocks so tightly that even a knife blade can’t pass between them. This polygonal masonry, built without mortar, withstands earthquakes better than many modern buildings. It’s a dazzling feat of ancient engineering.

Tiwanaku Stonework At Puma Punku

The Tiwanaku site in Bolivia features intricately cut andesite blocks, some weighing tons, fitted with precision grooves. While legends may exaggerate, the stoneworking skill remains remarkable. It proves pre-Columbian builders achieved techniques many assumed were impossible without modern tools.

Nazca Aqueducts

The Nazca people built spiral walkways leading into underground aqueducts, known as puquios, which continue to deliver water to this day. Their hydraulic engineering in one of the driest places on Earth feels remarkably ahead of its time.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Terracotta Army Crossbows

Among Qin Shi Huang’s buried warriors, archaeologists found standardized bronze crossbow triggers. Mass-produced with interchangeable parts, they represent an early form of industrial production. This discovery alters our understanding of military technology and organization in ancient China.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Chinese Cast Iron Techniques

Ancient Chinese smelters pioneered large-scale cast iron production long before Europe. This was during the Zhou and Han periods, when they engineered sophisticated tools and monumental structures—an industrial leap that predated the West by centuries.

Thomas Quine, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Quine, Wikimedia Commons

Roman Cameo Glass

The Portland Vase and similar works showcase Roman mastery of multi-layered glass. Back then, craftsmen carved through colored layers to reveal intricate images in techniques that were never fully replicated until recently. What this tells us is that Roman materials science had developed earlier than we had thought.

Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., Wikimedia Commons

Photograph by Mike Peel (www.mikepeel.net)., Wikimedia Commons

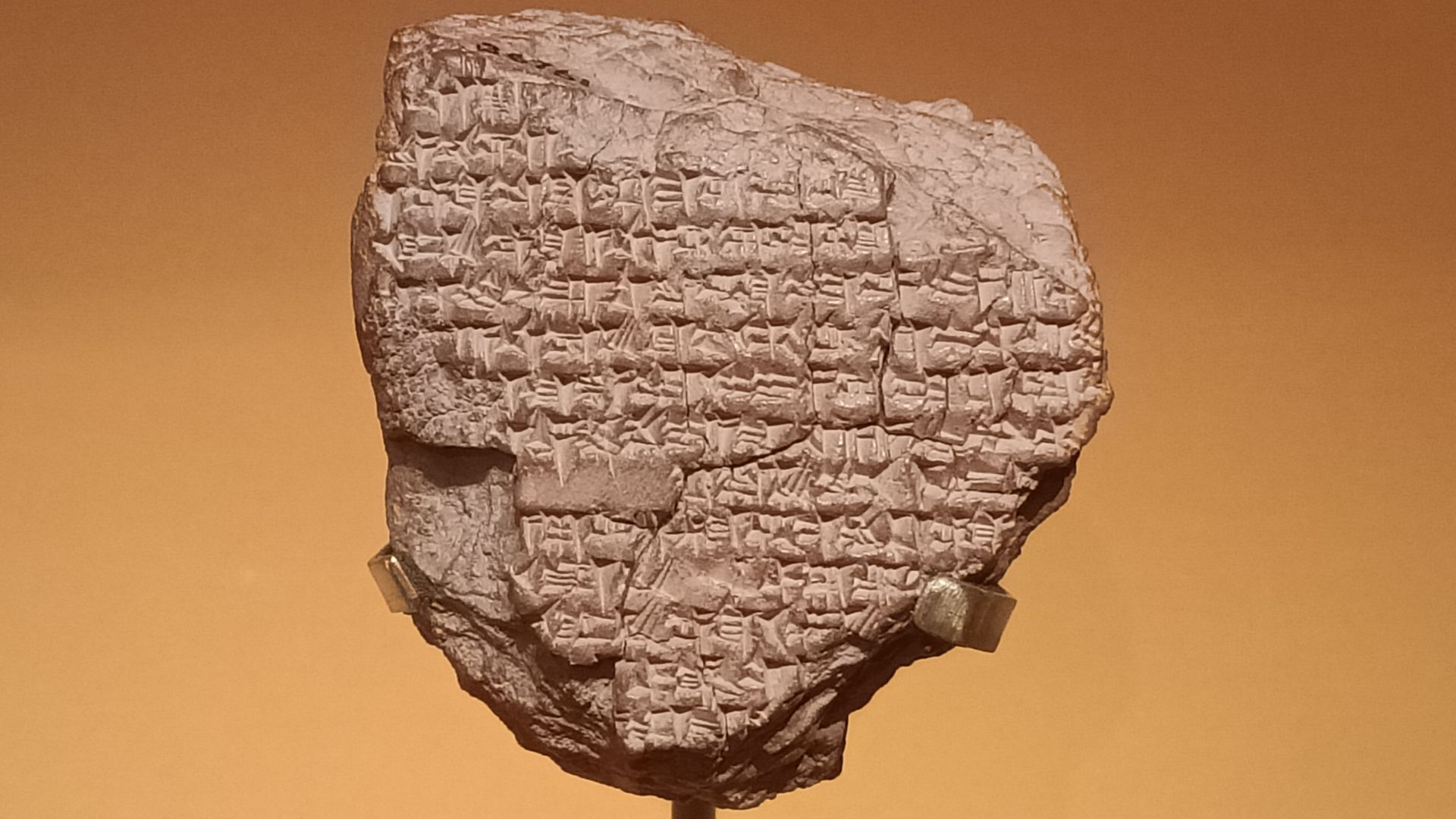

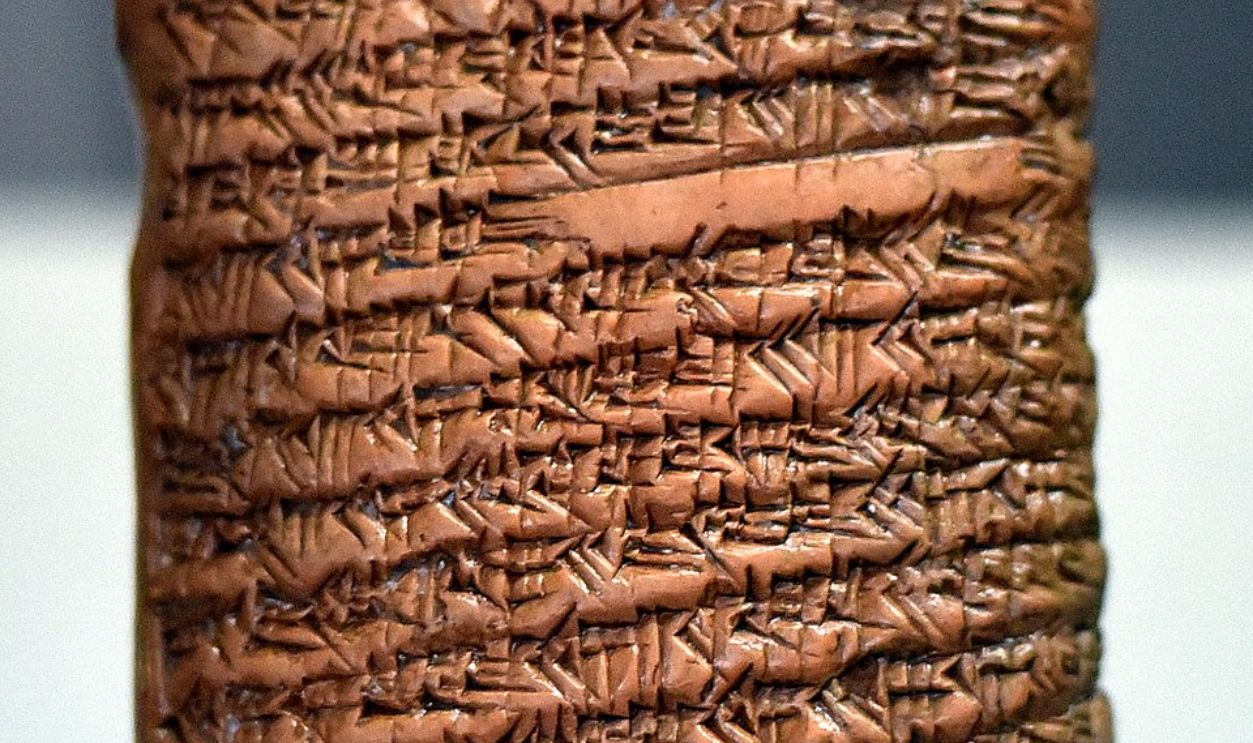

Babylonian Astronomical Diaries

For centuries, Babylonian scribes recorded the night sky in meticulous detail. By 400 BCE, they could predict planetary positions with astonishing accuracy. These texts provide evidence that scientific observation and continuity, as we know them today, were already established in the ancient world.

Brigade Piron, Wikimedia Commons

Brigade Piron, Wikimedia Commons

Olmec Colossal Heads

Weighing up to 40 tons each, the Olmec heads of Mexico were carved and transported without the use of wheels or beasts of burden. Their creation required sophisticated logistics and immense labor coordination, which makes them an engineering marvel of the pre-Columbian Americas.

Maya Rubber Processing

The ancient Maya learned to mix latex with plant extracts to produce durable, elastic rubber. They used it for sandals and waterproofing. This inventive chemistry, achieved over 3,000 years ago, is one of the earliest examples of polymer science.

Blue Plover, Wikimedia Commons

Blue Plover, Wikimedia Commons

Indus Valley Sanitation

Cities like Mohenjo-Daro featured standardized bricks and private toilets connected to a central sewage system. More than 4,000 years ago, the Indus people enjoyed sanitation that many later societies would lack. Their urban planning seemed way, way advanced.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

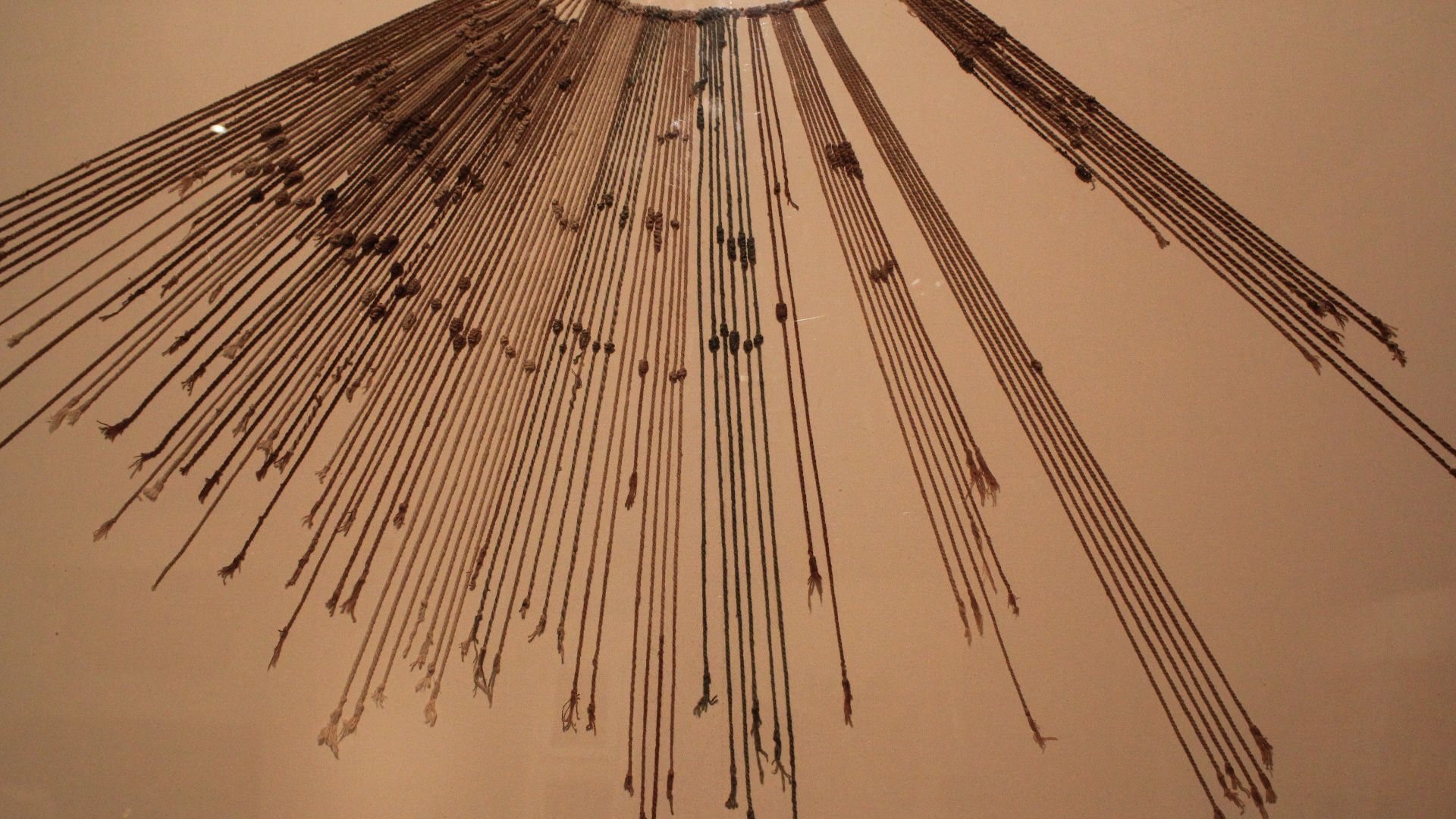

Quipu Knot Records

Instead of writing, Andean cultures recorded data with knotted cords known as quipus. They tracked tribute, census information, and stories in this way. This non-alphabetic system of information storage challenges the idea that only scripts could sustain complex administration in the ancient world.

Newgrange Passage Tomb

Built around 3200 BCE in Ireland, Newgrange aligns so that sunlight floods its inner chamber only on the winter solstice. The precision required to achieve this alignment demonstrates advanced astronomical knowledge among Neolithic builders, rewriting what we expected from early European societies.

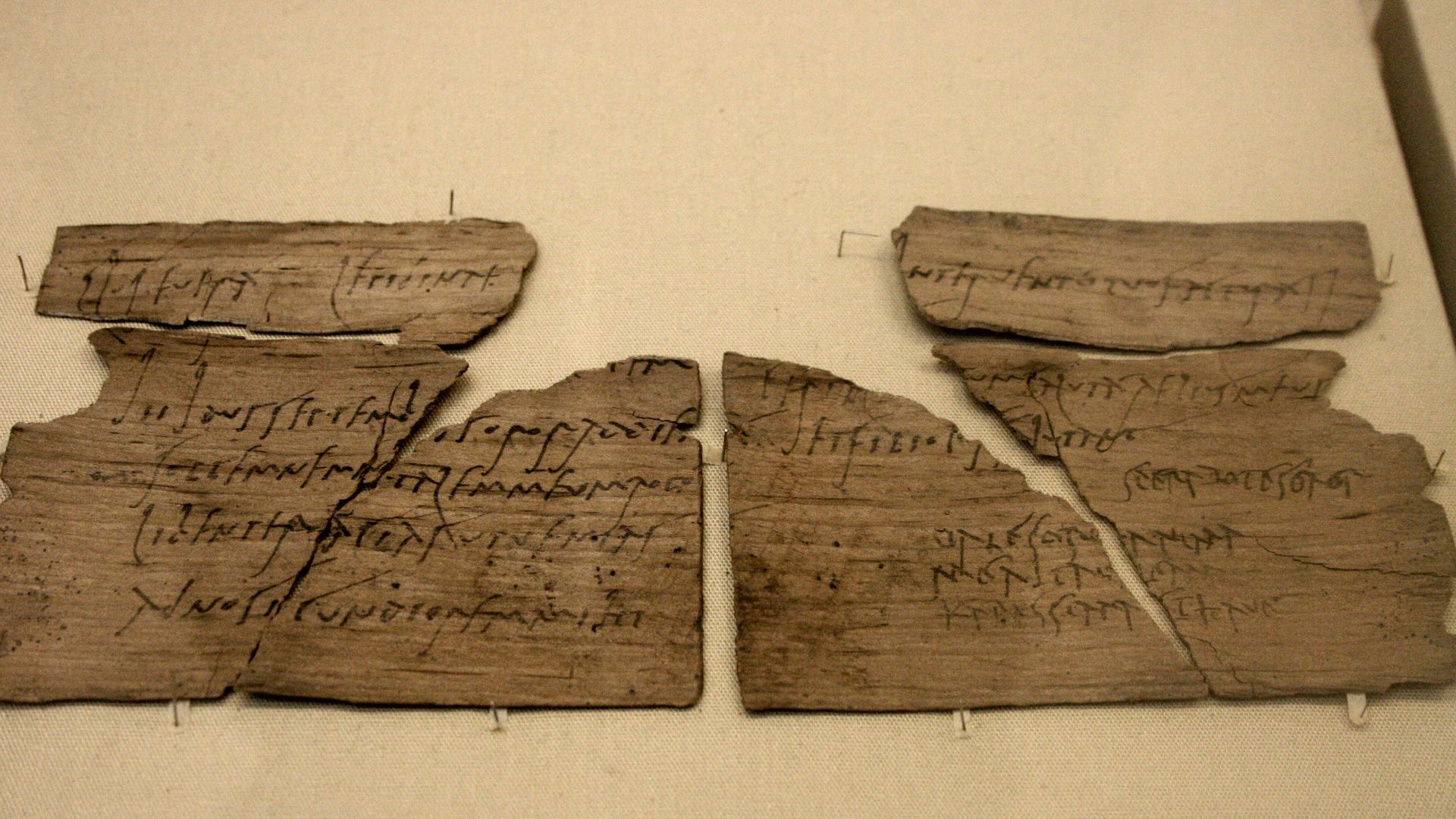

Vindolanda Writing Tablets

Unearthed near Hadrian’s Wall, thin wooden tablets preserved personal letters from Roman Britain. They reveal widespread literacy and a surprisingly connected society on the empire’s edge. In a way, they were the text messages or emails of their time, keeping people linked across distance.

Persian Qanats

Underground aqueducts tapped groundwater and delivered it miles to fields and towns across Persia. Dating back over 2,500 years, these qanats were a masterstroke of engineering in arid environments—many still function to this date.

Ninara from Helsinki, Finland, Wikimedia Commons

Ninara from Helsinki, Finland, Wikimedia Commons

Su Song’s Astronomical Clock Tower

Though slightly later than most entries, Su Song’s 11th-century clock tower in China deserves a place here. It featured complex gearing, chain drives, and a celestial globe. For its time, it was centuries ahead of European clockmaking.

Original uploader was Kowloonese at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Original uploader was Kowloonese at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Nok Terracottas

In Nigeria, the Nok culture created life-sized terracotta sculptures over 2,500 years ago. Their artistry and technical skill appear suddenly, with no clear precedent. And it makes you wonder—how many breakthroughs in art and technology still lie hidden, waiting to rewrite our history?

Jomon Lacquerware

The Jomon people of Japan developed lacquer techniques as early as 7000 BCE. They would coat wooden vessels with a glossy, protective finish. Their glossy vessels remind us that the everyday materials we take for granted—like plastics and protective finishes—have ancient origins.

Sumerian Mathematics

Clay tablets from Mesopotamia reveal base-60 calculations capable of predicting eclipses and planetary movements. This sophisticated system laid the foundation for geometry and astronomy. It appears startlingly advanced, and it was.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Archimedes’s Screw

Despite the Archimedean screw being a simple device, it could efficiently raise water using rotational force. Described by Archimedes around 234 BCE after his time in Egypt, earlier versions may have existed in Mesopotamia, with some linking it to the irrigation of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Cavaliere grande, Wikimedia Commons

Cavaliere grande, Wikimedia Commons

South-Pointing Chariot

Chinese texts describe a vehicle whose figure always pointed south, regardless of the turns it made. So, how did it work? This vehicle worked through differential gears centuries before they appeared in Europe. The misconception this debunks is that mechanical principles are modern.