The Bakery Life Wasn’t Gentle

Victorian bakeries looked simple on the surface, yet the daily rhythm behind those doors held far more tension than anyone strolling by would guess. The trade carried its own mix of pressure, effort, and surprises that shaped every shift.

Waking At Midnight To Start The Day

Most Victorian bakers rolled out of bed around midnight because customers expected fresh bread at dawn. That early start wasn’t optional. Towns ran on morning loaves, so bakers worked while streets stayed silent and most households still slept through the darkest hours.

Living Above The Bakehouse For Constant Access

Plenty of bakers lived in cramped rooms right above their ovens. Rent was cheaper, and the short walk mattered when the workday began before sunrise. It also meant the bakery’s noises and smells drifted into their living space, which was not a great work-life balance.

Beginning Work In Cold Unheated Rooms

When bakers first stepped downstairs, the workspace felt icy. Many bakehouses avoided burning fuel overnight, so the morning chill lingered until the ovens finally caught. Workers started their shift bundled up, waiting for the heat that would later turn the room into an oven itself.

Mixing Heavy Dough Entirely By Hand

Dough was mixed by hand, and big bakeries handled batches weighing well over a hundred pounds. It took real muscle to push, fold, and lift that mass for long stretches. By sunrise, many bakers felt as if they’d already done a full day’s workout.

Hauling Water Before Any Baking Began

Running water wasn’t guaranteed, so bakers often fetched buckets from a well or street pump before anything else. The trip happened in the dark, sometimes multiple times, just to fill the troughs. It added another layer of labor before the dough was even touched.

Warren LeMay from Covington, KY, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Warren LeMay from Covington, KY, United States, Wikimedia Commons

Relying On Unpredictable Yeast Quality

Victorian yeast didn’t come in tidy packets. Bakers used brewers’ yeast or homemade starters, and both changed daily. A batch could rise beautifully one morning and fall flat the next, leaving bakers relying on instinct more than measurements to keep their bread consistent.

Rebecca Siegel, Wikimedia Commons

Rebecca Siegel, Wikimedia Commons

Handling Flour Adulterated By Dishonest Suppliers

Flour wasn’t always pure. Some millers stretched their product with chalk or ground rice to boost profits. Bakers who bought cheaper flour had to deal with dough that behaved strangely and customers who blamed them when loaves tasted sharp or off.

Robert Breitinger , Wikimedia Commons

Robert Breitinger , Wikimedia Commons

Correcting Inconsistent Ingredient Measurements

Scales varied widely between shops, and many bakers worked with worn weights that didn’t stay accurate. Recipes weren’t exact either. Workers had to adjust by sight, feel, and experience, fixing mistakes as they went and hoping each batch balanced out by baking time.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Firing Early Ovens With Coal Or Wood

Ovens needed long firing before use, and that meant hauling fuel and feeding flames until the chamber reached baking heat. The job left bakers sweaty before the day even began, and coal especially filled the workspace with soot that clung to everything.

Judging Oven Heat Without Thermometers

In the Victorian era, most ovens had no built-in thermometer, so bakers checked the temperature with tricks. A handful of flour tossed inside told them if the heat was ready based on how fast it browned. It looked simple, but accuracy depended entirely on experience and timing.

Using Dough Troughs That Rarely Stayed Clean

Wooden troughs absorbed moisture, trapped crumbs, and were difficult to scrub fully. Even careful bakeries struggled with lingering odors and buildup. Many shops reused the same trough for years, creating conditions that encouraged bacteria and pests long before modern hygiene standards existed.

BERNARDOT Claude-Henry, Wikimedia Commons

BERNARDOT Claude-Henry, Wikimedia Commons

Breathing Air Thick With Flour Dust

Flour hung in the air as soon as workers started mixing or sifting. In small bakehouses, that haze settled into lungs day after day. Many bakers developed chronic coughing and irritation because no one had ventilation systems or masks to protect them.

The Danger Of The Doughman's Itch

Bakers constantly worked with wet dough and flour. This led to serious, painful skin problems like eczema and severe rashes. This chronic condition was commonly known as the "doughman's itch" or "baker's scab", and it was a terrible, constant hazard.

Suffering Frequent Burns Near Scorching Ovens

Burns were almost guaranteed. Bakers handled long paddles, hot trays, and oven doors without modern gloves. A small slip could mean blistered fingers or scorched skin. Even experienced workers carried scars because daily exposure made accidents feel like part of the job.

Facing Strict Laws On Bread Quality

Victorian bread had rules. The 1836 Bread Act and later regulations targeted dishonest bakers who mixed fillers into dough. Inspectors could check loaves without warning, and a single bad batch risked fines or angry customers who considered bread one of their most important staples.

Training Through Grueling Apprentice Hours

Many bakers started as apprentices in their early teens, working long days for very little pay. They swept floors, hauled ingredients, and learned every task by repetition. Sleep was scarce, and quitting wasn’t simple because apprenticeships were often legal agreements that tied them to the shop.

Dealing With Rats And Insects Around Grain

Stored grain attracted pests, especially in crowded cities. Bakers fought rats and beetles constantly because sacks of flour made easy targets. Keeping supplies clean took daily effort, and any infestation risked ruining ingredients that were already expensive to replace.

The Secret Behind The Baker's Dozen

The extra loaf given in a "baker's dozen" (13 instead of 12) was not a gift. Bakers worried about government inspectors checking loaves for short weight. Adding the extra loaf was a nervous tactic to avoid heavy fines and accusations of cheating customers.

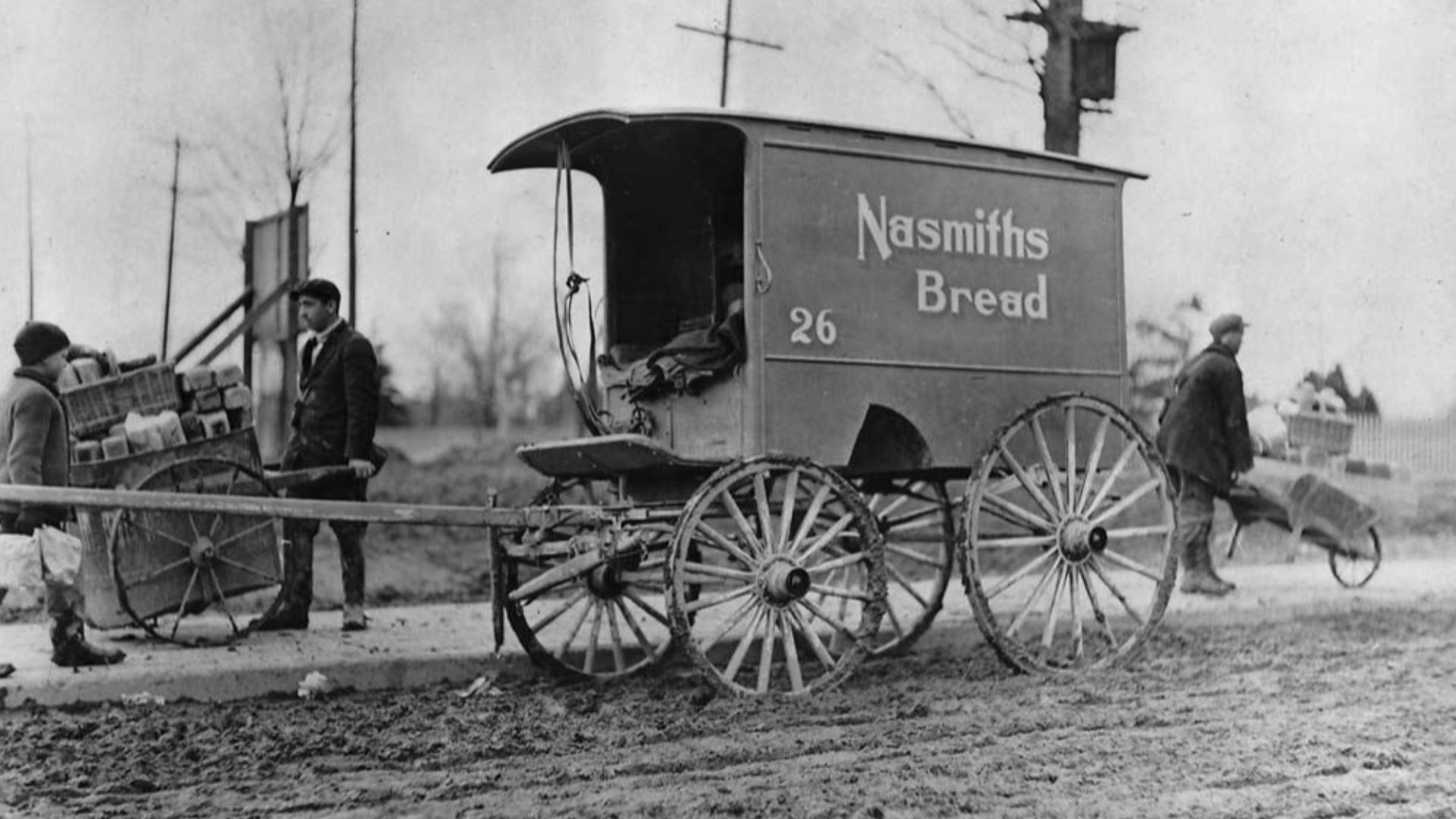

Delivering Bread Through Harsh City Streets

Bread deliveries meant carrying heavy baskets through rain and busy Victorian streets. Bakeries didn’t rely on vehicles for short routes, so workers walked door to door. Customers expected fresh loaves early, leaving bakers hustling outside after hours already spent working indoors.

William James, Wikimedia Commons

William James, Wikimedia Commons

Competing In A Crowded Bakery Market

Victorian cities held many small bakehouses, and customers were quick to switch to a cheaper loaf. Bakers fought to keep prices low while covering rising costs of flour and fuel. Staying afloat meant working harder and not charging more, just to keep regular buyers.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Managing Rapid Spoilage With No Preservation

Bread didn’t last long in the nineteenth century. Without preservatives or plastic wrap, yesterday’s loaf hardened fast. Unsold bread meant real losses, so bakers had to predict demand closely, hoping weather, markets, or unexpected crowds didn’t throw off their careful calculations.

Being Blamed When Bakery Fires Broke Out

Bakehouses were known fire hazards thanks to coal ovens and constant heat. When flames spread, neighbors often pointed to the bakery first. Even careful shops faced suspicion because one spark could jump to nearby buildings packed tightly along Victorian streets.

David Bjorgen, Wikimedia Commons

David Bjorgen, Wikimedia Commons

Baking For The Poor: The Tommy Shop System

In factory towns, bakers were often forced to accept credit slips or tokens (the "tommy system") instead of real cash from factory owners. This made it very difficult for the baker to get actual money, which was needed to buy essential flour and fuel.

Community Archives, Wikimedia Commons

Community Archives, Wikimedia Commons

The Hidden Tax: Paying With Beer Money

Bakers often had to give their workers (journeymen) part of their pay as "beer money" or free ale. This unwritten rule was a normal, expected cost of hiring staff. This old tradition reduced the owner's cash profits and made running the business harder.

National Museum of American History , Wikimedia Commons

National Museum of American History , Wikimedia Commons

Facing Short Careers Due To Physical Strain

The constant lifting, kneading, and night shifts took a real toll. Many bakers developed joint pain, breathing problems, or chronic exhaustion by middle age. Some shifted to lighter tasks, but plenty left the trade early simply because their bodies couldn’t handle the workload anymore.