No Neurons Necessary

Nature hides animals that make survival look effortless. They regenerate, filter, and adapt in almost unreal ways. Their secret? Simplicity. What seems basic at first glance is actually nature’s most reliable design.

Sea Anemones

Their survival strategy is elegantly simple yet brutally effective: wait, sense, and strike. Using a decentralized nerve net similar to jellyfish, sea anemones can detect the slightest vibration or chemical signature of approaching prey. When a fish brushes against their tentacles, thousands of stinging cells fire simultaneously.

Bernard Spragg. NZ from Christchurch, New Zealand, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Spragg. NZ from Christchurch, New Zealand, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Anemones (Cont.)

This paralyzes the victim before the anemone's muscular body contracts to stuff the meal into its central mouth. Many species form partnerships with clownfish to provide protection in exchange for cleaning services and nutrients from fish waste. These are famously known as “flowers of the sea”.

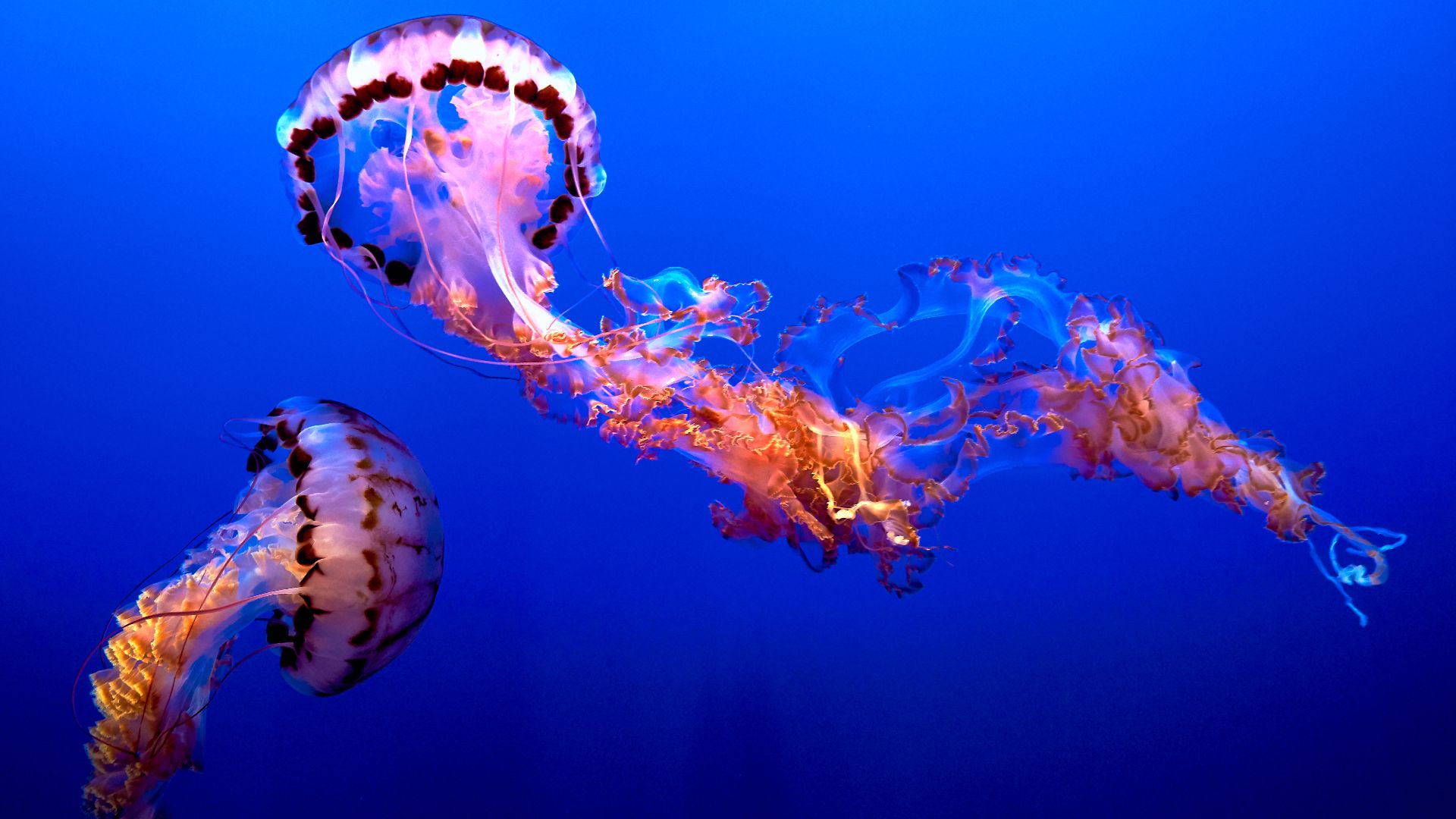

Jellyfish

Jellyfish have witnessed the rise and fall of countless species, yet continue to thrive in every ocean on Earth, from the frigid Arctic waters to tropical lagoons. Some species, like the immortal jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii, can actually reverse their aging process and theoretically live forever.

Miguel Angel Omaña Rojas, Wikimedia Commons

Miguel Angel Omaña Rojas, Wikimedia Commons

Jellyfish (Cont.)

What makes jellyfish truly remarkable isn't what they have, but what they don't have. No brain, no heart, no blood, and no central nervous system. They operate on a simple but effective nerve net that spans their entire bell-shaped body, allowing them to detect light and sense touch.

Pedro Szekely from Los Angeles, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Pedro Szekely from Los Angeles, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Jellyfish (Cont.)

A 2025 study by Fabian Pallasdies and Prof Dr Susanne Schreiber at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin used a coupled nerve-muscle-fluid simulation to explain how electrical activity in the jellyfish’s nerve ring triggers rapid and symmetrical muscle contractions to stabilize swimming direction.

Corals

Scientists estimate that coral reefs support approximately 25% of all marine animals despite covering less than 1% of the ocean floor. A single coral colony can contain thousands of individual polyps, each no bigger than a grain of rice.

Corals (Cont.)

The Great Barrier Reef stretches over 1,400 miles. These living cities process enormous amounts of water daily, with some large coral heads filtering thousands of gallons per day. Every coral polyp builds its home by extracting calcium carbonate from seawater to form a limestone skeleton.

Wise Hok Wai Lum, Wikimedia Commons

Wise Hok Wai Lum, Wikimedia Commons

Corals (Cont.)

These reefs are said to protect coastlines as they absorb wave energy, reduce damage from storms, hurricanes, and tsunamis, and prevent coastal erosion. Coral reefs also support local economies worldwide through fisheries and tourism by providing food and jobs to millions.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Portuguese Man O'War

This one represents one of nature's most successful experiments in collective living. It's not actually a single animal but a colonial organism called a siphonophore, consisting of four specialized types of polyps that cannot survive independently. Every polyp performs a specific function.

Bengt Nyman from Vaxholm, Sweden, Wikimedia Commons

Bengt Nyman from Vaxholm, Sweden, Wikimedia Commons

Portuguese Man O'War (Cont.)

So, the pneumatophore acts as a gas-filled sail, the dactylozooids form the deadly tentacles, the gastrozooids handle digestion, and the gonozooids take care of reproduction. This floating city can have tentacles extending up to 165 feet below the surface.

Jules Verne Times Two, Wikimedia Commons

Jules Verne Times Two, Wikimedia Commons

Hydras

Hydras possess what scientists consider biological immortality—under ideal laboratory conditions, they show no signs of aging and can survive through continuous regeneration. These freshwater polyps, just 10 millimeters long, can regenerate their entire body from a fragment as small as 1/300th of their original size.

Przemysław Malkowski, Wikimedia Commons

Przemysław Malkowski, Wikimedia Commons

Hydras (Cont.)

It has been revealed that they can even regrow their heads within 72 hours of decapitation, with the new head containing all the necessary sensory structures and feeding apparatus. Hydras operate with a nerve net so simple that it contains only around 15,000 neurons.

Sea Stars (Starfish)

The remarkable regenerative abilities of sea stars border on the supernatural. If you cut one into five pieces, and each piece contains part of the central disc, you could potentially end up with five completely new starfish within a year.

Sea Stars (Cont.)

This incredible superpower is possible because sea stars store vital organs throughout their arms rather than centralizing them in one location. Some species can even deliberately shed an arm when grabbed by a predator, a process called autotomy, then regrow the lost limb over several months.

Nhobgood Nick Hobgood, Wikimedia Commons

Nhobgood Nick Hobgood, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Urchins

Armed with thousands of razor-sharp spines that can rotate 360 degrees, sea urchins are the ocean's living pincushions. These are capable of wedging themselves into rock crevices so tightly that storms cannot dislodge them. Their spines aren't just for protection, though.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Urchins (Cont.)

They also serve as stilts for walking across the seafloor, with some creatures able to "walk" up to 50 centimeters per day in search of food. The most venomous species, found in tropical Indo-Pacific waters, have spines that can penetrate wetsuit material and inject painful toxins.

Frédéric Ducarme, Wikimedia Commons

Frédéric Ducarme, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Cucumbers

When threatened, sea cucumbers react with one of nature's most dramatic magic tricks. They literally throw their guts at predators by violently contracting their body muscles and ejecting their internal organs through their rear end. This process is called evisceration.

Nevit Dilmen (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Nevit Dilmen (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Sea Cucumbers (Cont.)

It serves as the ultimate distraction technique, giving the sea cucumber time to escape while the predator is busy investigating the expelled organs. Remarkably, the animal can regenerate all its lost internal organs, including respiratory trees, digestive tract, and reproductive organs, within just a few weeks.

Chamberlain of Nilai, Wikimedia Commons

Chamberlain of Nilai, Wikimedia Commons

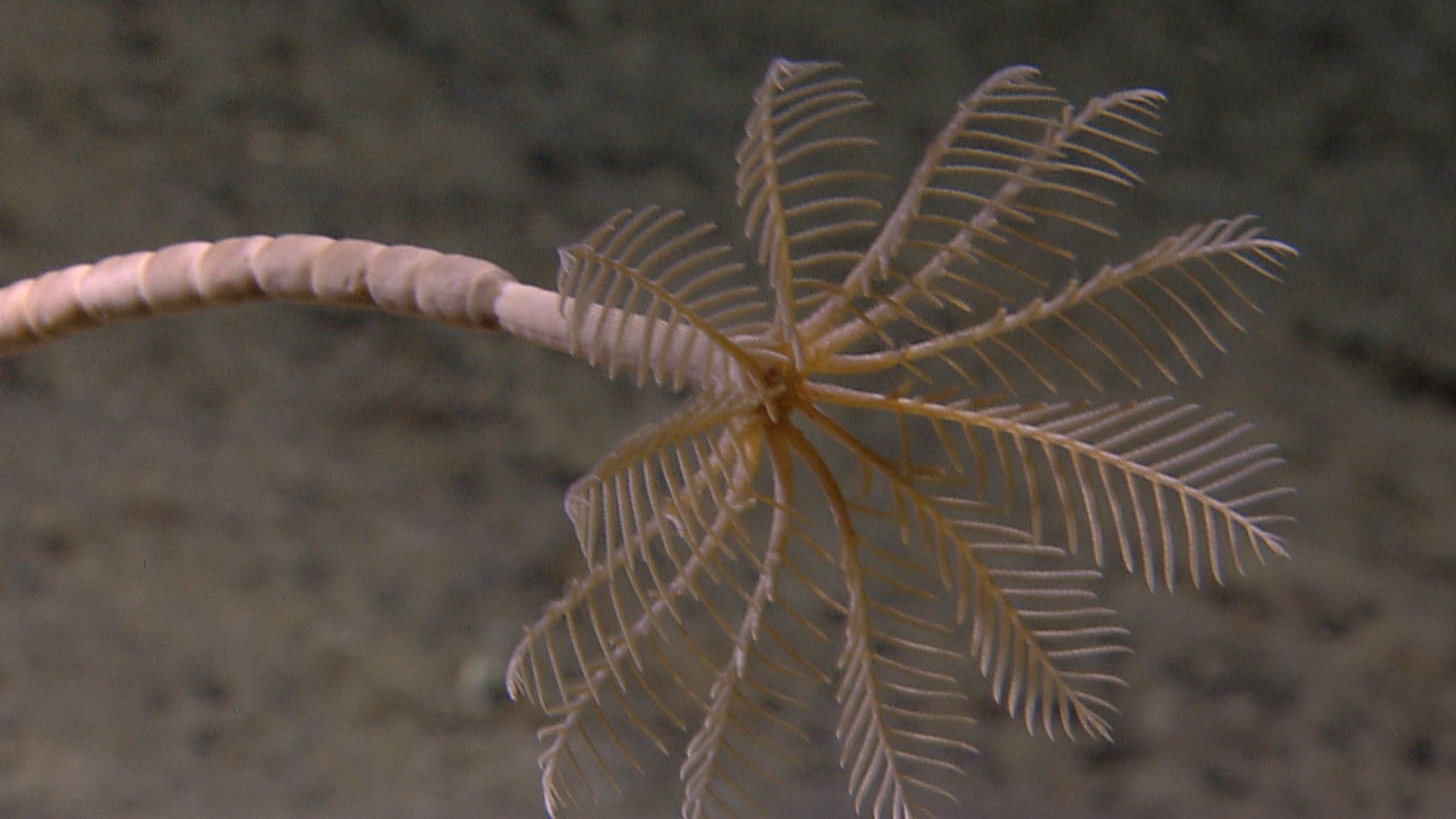

Sea Lilies (Crinoids)

Sea lilies are living fossils that have remained virtually unchanged for over 450 million years. These creatures were so abundant during the Paleozoic era that their fossilized remains form entire limestone formations. That period earned the nickname “Age of Crinoids”.

NOAA Photo Library, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA Photo Library, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Lilies (Cont.)

Today, only about 600 species survive, with most living in deep ocean waters where they can avoid the storms and predators. Resembling underwater flowers swaying in the current, sea lilies use their feathery arms to filter microscopic plankton and organic particles from the water section.

NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, INDEX-SATAL 2010 via NOAA Photo Library, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, INDEX-SATAL 2010 via NOAA Photo Library, Wikimedia Commons

Brittle Stars

Brittle stars are the acrobats of the seafloor, capable of moving with amazing speed and agility using their five slender, snake-like arms that can twist and bend in styles that would make a contortionist jealous. Unlike their slower sea star cousins, brittle stars can quickly scurry across the ocean bottom.

Xaime Aneiros Vazquez, Wikimedia Commons

Xaime Aneiros Vazquez, Wikimedia Commons

Brittle Stars (Cont.)

Their arms are so delicate that they break easily when handled, hence the name “brittle”. However, this fragility is actually a survival strategy. Brittle stars are actually more diverse and can be found in every ocean, from shallow tide pools to the deepest trenches.

NOAA Ocean Exploration & Research from USA, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA Ocean Exploration & Research from USA, Wikimedia Commons

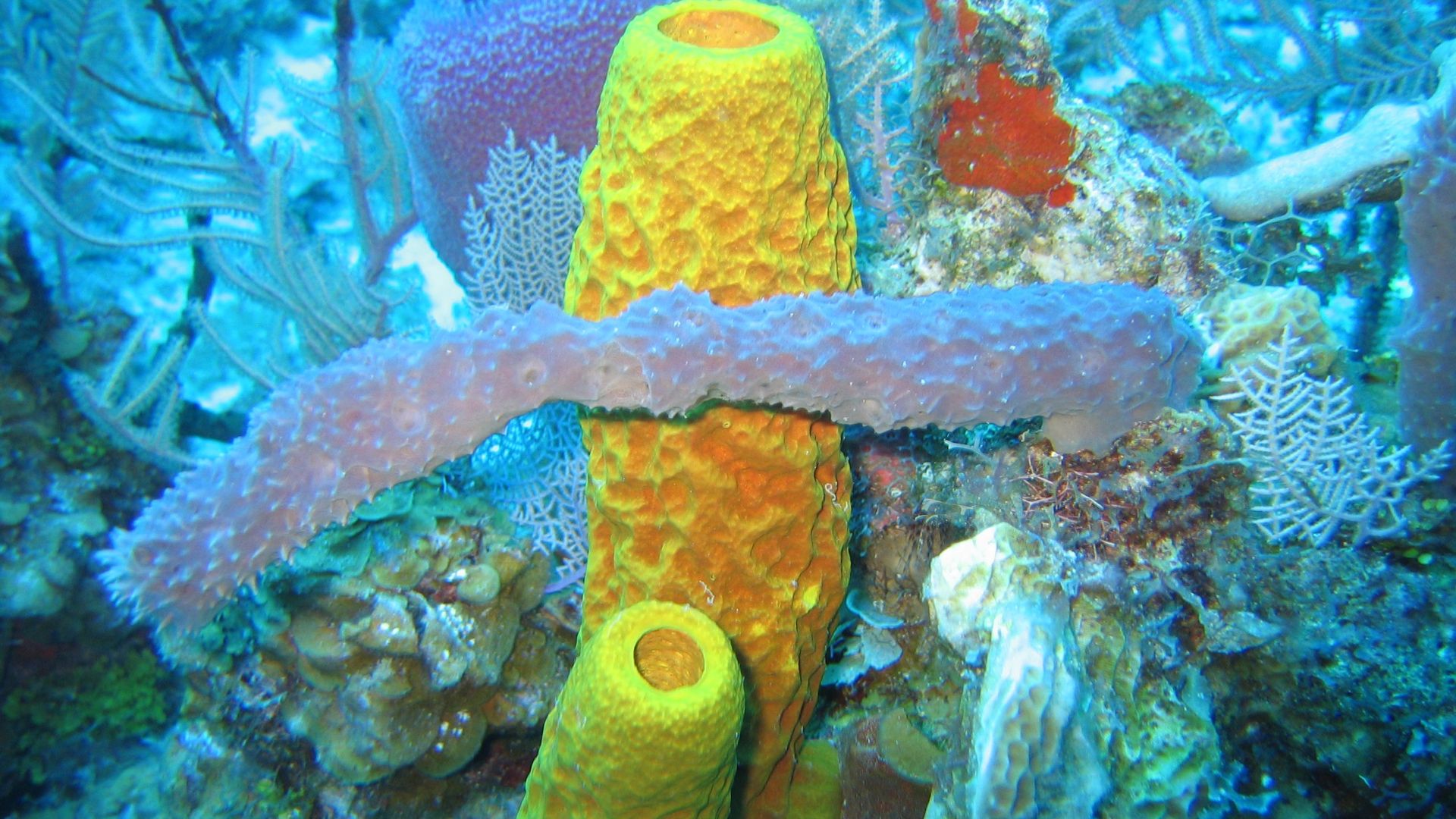

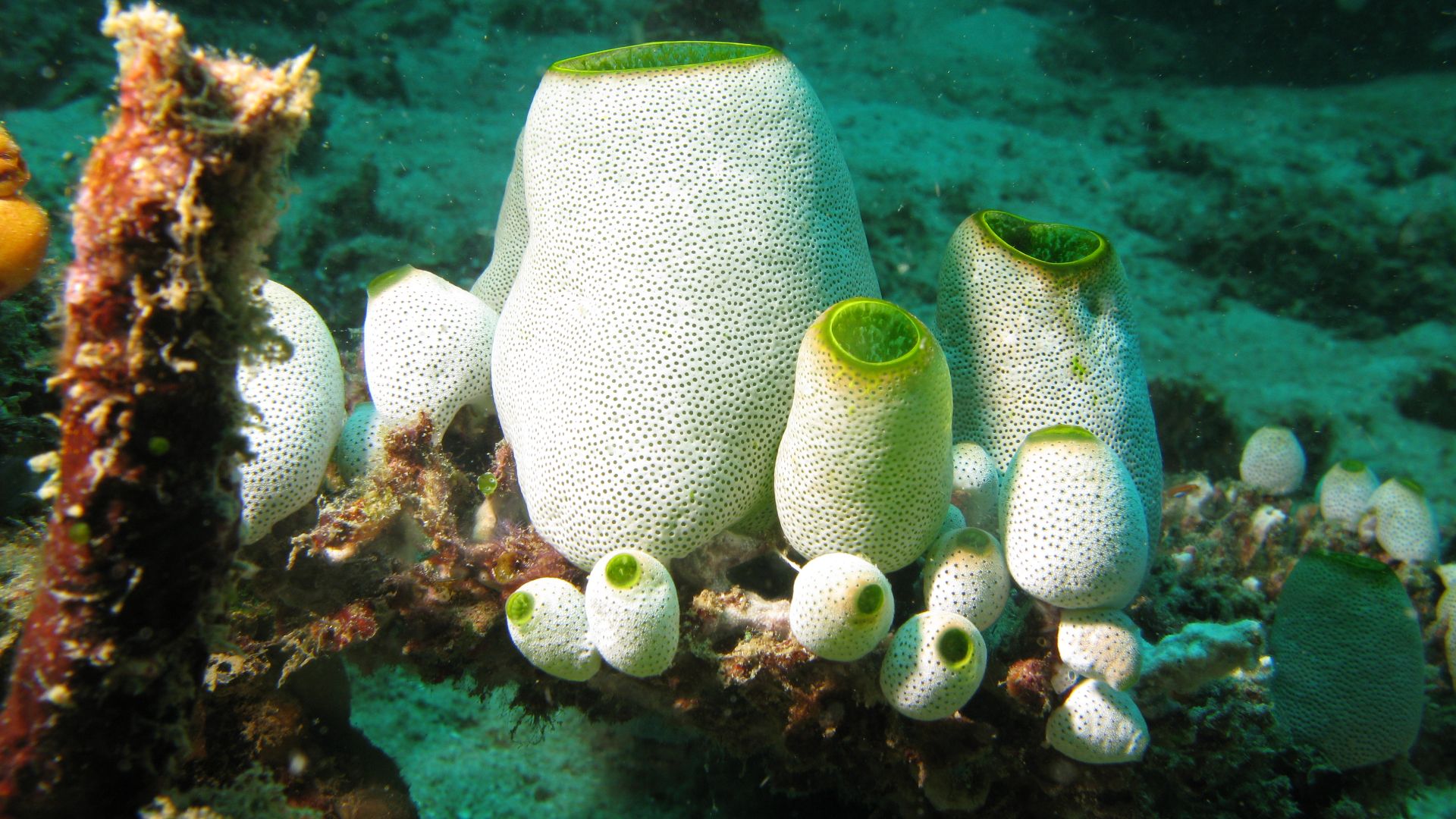

Sea Sponges

Earth's oldest multicellular animals are living witnesses to every major extinction event in planetary history. These ancient filter-feeders are so efficient at their job that a single large sponge processes over 20,000 times its own body volume of water each day, removing bacteria, viruses, and organic particles.

Steve Rupp, National Science Foundation, Wikimedia Commons

Steve Rupp, National Science Foundation, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Sponges (Cont.)

They do not possess organs, tissues, or even basic body symmetry. They're essentially organized colonies of specialized cells working together without any central coordination. Their bodies are riddled with thousands of microscopic pores and channels that craft a sophisticated plumbing system.

Twilight Zone Expedition Team 2007, NOAA-OE., Wikimedia Commons

Twilight Zone Expedition Team 2007, NOAA-OE., Wikimedia Commons

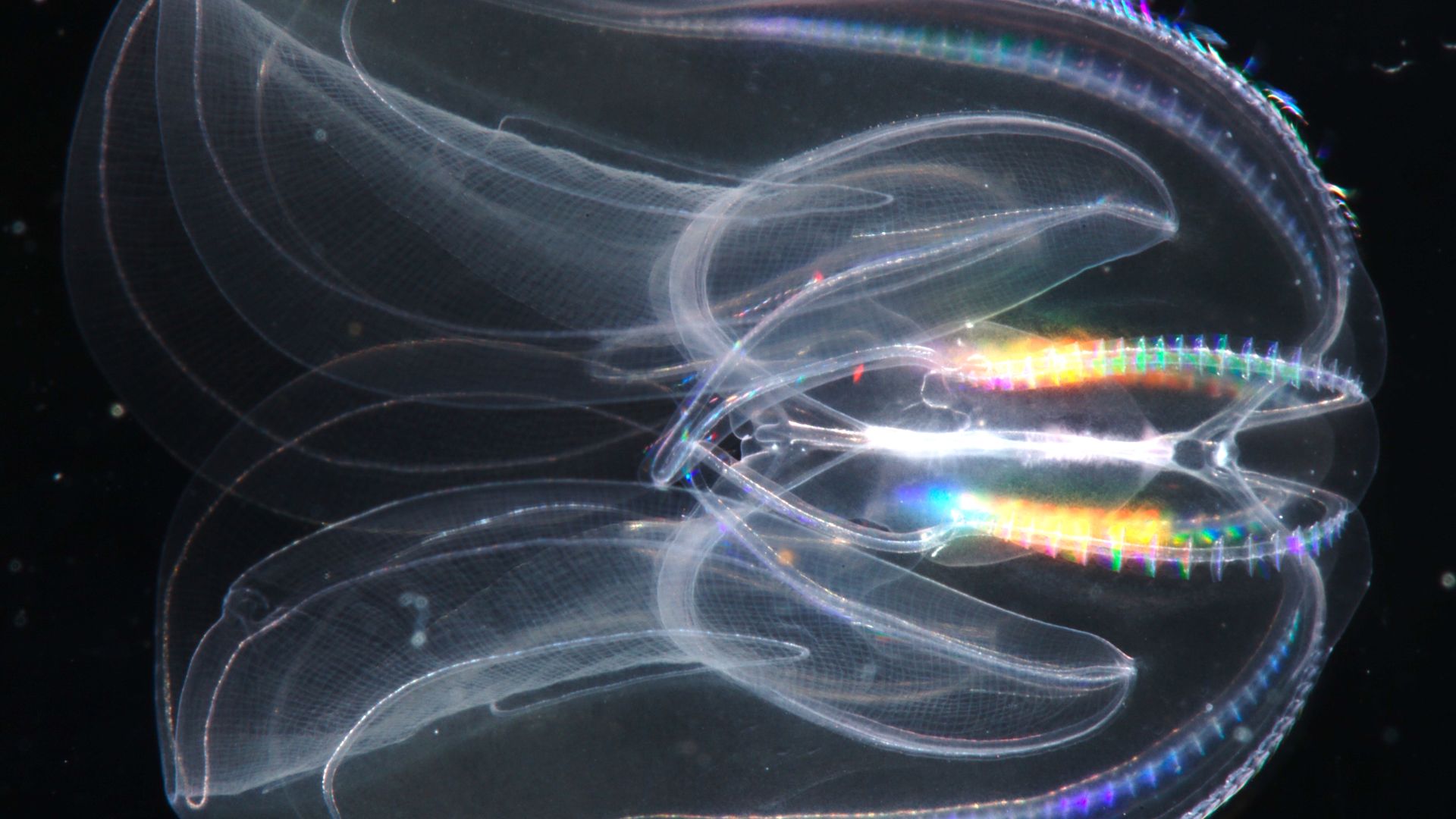

Comb Jellies (Ctenophores)

Comb jellies are the ocean's living prisms. They radiate mesmerizing rainbow light shows as they pulse through the water using eight rows of hair-like cilia that diffract light into spectacular color displays. These ethereal creatures are the largest animals that use cilia for locomotion.

Bruno C. Vellutini, Wikimedia Commons

Bruno C. Vellutini, Wikimedia Commons

Comb Jellies (Cont.)

Comb jellies capture prey using sticky tentacles armed with specialized cells called colloblasts. These are molecular glue traps that snare small organisms without the painful stings. Comb jellies independently evolved a nervous system completely different from all other animals—they use unique neurotransmitters and have neural pathways.

National Marine Sanctuaries, Wikimedia Commons

National Marine Sanctuaries, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Squirts (Tunicates)

The life story of sea squirts reads like a science fiction novel. They begin life as free-swimming larvae with a primitive spinal cord, brain, and tail, resembling tiny tadpoles with vertebrate-like features. However, when they find a suitable surface to attach to, they undergo a dramatic change.

Silke Baron, Wikimedia Commons

Silke Baron, Wikimedia Commons

Sea Squirts (Cont.)

They literally digest their own brain and nervous system, absorbing these complex structures as they metamorphose into sedentary, filter-feeding organisms. This bizarre process of neural self-destruction occurs because they no longer need navigation systems once they commit to a stationary lifestyle.

Silke Baron, Wikimedia Commons

Silke Baron, Wikimedia Commons

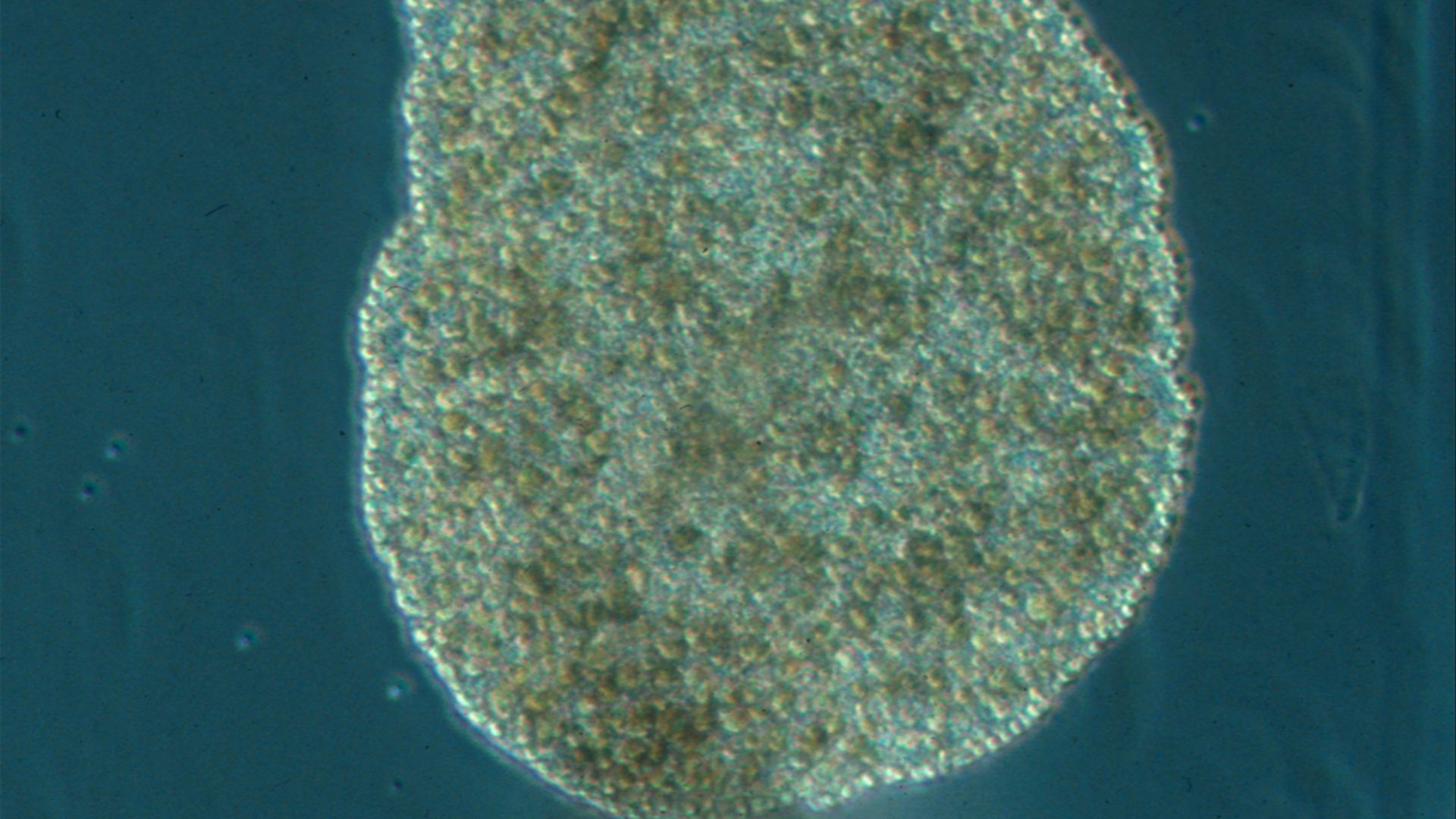

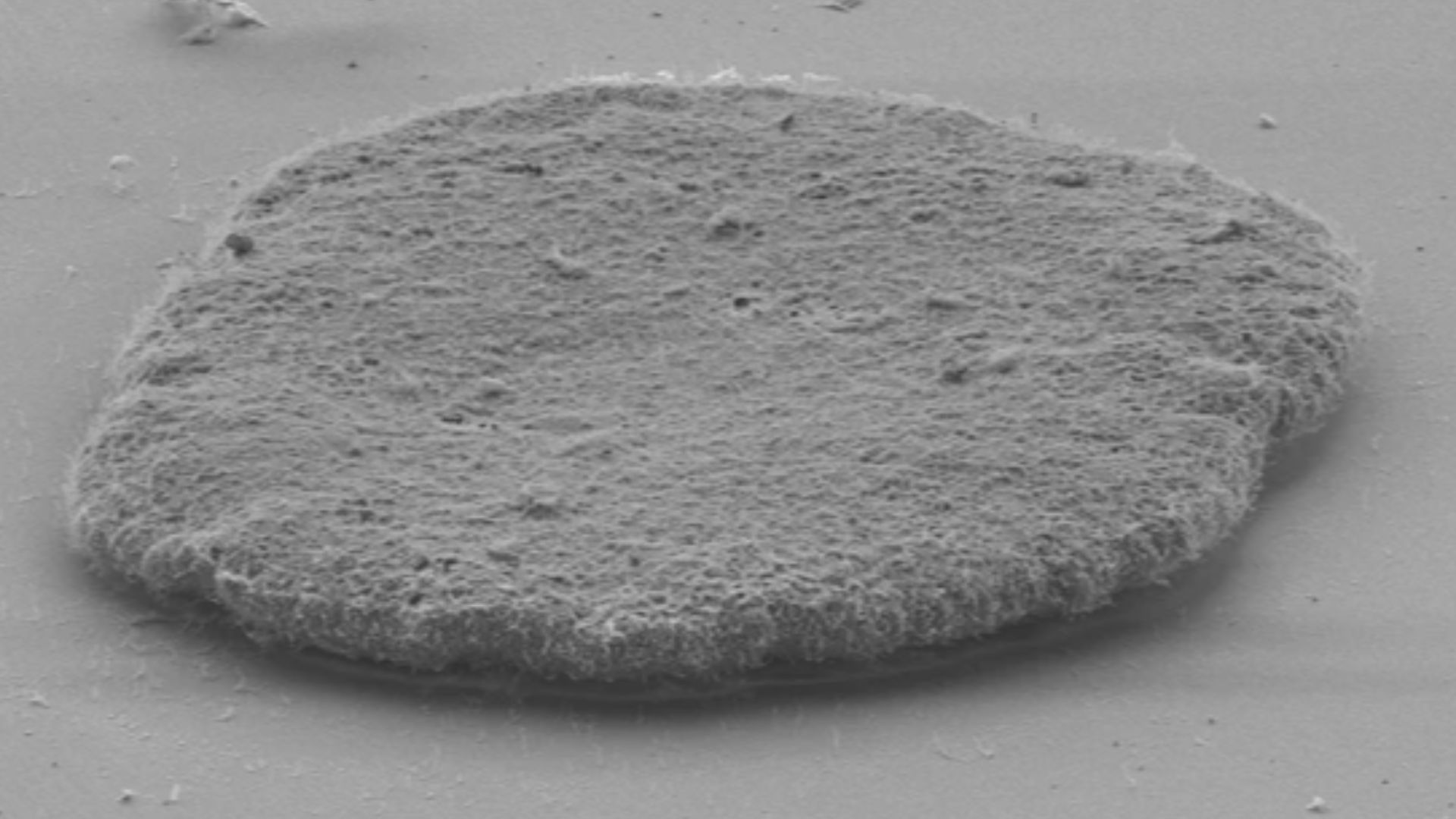

Placozoans

Placozoans are nature's ultimate minimalists. Imagine an animal so simple it makes an amoeba look complex by comparison. These microscopic marine creatures consist of just a few thousand cells arranged in only three layers, with no organs, no tissues, no symmetry, and no specialized body parts.

Bernd Schierwater, Wikimedia Commons

Bernd Schierwater, Wikimedia Commons

Placozoans (Cont.)

Discovered in 1883 but largely ignored for over a century, placozoans were so basic that scientists initially thought they were damaged specimens of other animals rather than a distinct group worthy of their own phylum. Despite their extreme simplicity, they can locate food sources and move toward favorable conditions.

Image credit: Michael G. Hadfield, Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: Michael G. Hadfield, Wikimedia Commons

Clams

Looking for homebodies of the ocean? Here you go. Some species, like the giant geoduck, live for over 160 years while barely moving from their chosen spot in the sediment. These bivalve mollusks operate using three pairs of nerve clusters called ganglia.

Clams (Cont.)

One for the foot, one for the digestive system, and one for the siphons that coordinate basic functions without any centralized brain. The geoduck clam, despite its suggestive appearance, holds the record as one of the longest-living animals on Earth, with the oldest recorded specimen reaching 168 years old.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

Oysters

Nature's gender-fluid artists are capable of changing gender multiple times throughout their lives, depending on environmental conditions and population needs. They typically start as males when young, with limited energy reserves, and then switch to females as they grow larger.

TrimmerinWiki, Wikimedia Commons

TrimmerinWiki, Wikimedia Commons

Oysters (Cont.)

Such fantastic flexibility allows oyster populations to optimize their reproductive success without any conscious decision-making process. A single oyster filters about 50 gallons of water per day, making them living water treatment plants that remove excess nutrients, bacteria, and pollutants from coastal ecosystems.

Taishonambu, Wikimedia Commons

Taishonambu, Wikimedia Commons

Mussels

The engineering prowess of mussels has thrilled scientists and inventors alike. These humble bivalves produce one of nature's strongest underwater adhesives, secreting protein-based threads called byssal fibers that can withstand wave forces equivalent to hurricane-strength winds. Each thread is made of multiple proteins.

Andreas Trepte, Wikimedia Commons

Andreas Trepte, Wikimedia Commons

Mussels (Cont.)

Mussels demonstrate superb behavioral coordination, despite their simple nervous system of paired ganglia. When environmental conditions become stressful, they can synchronize their shell-closing responses across entire beds. This collective behavior helps protect the entire community from threats like predators or toxic algal blooms.

Photo credit: Tim Menard / USFWS. USFWS Mountain-Prairie, Wikimedia Commons

Photo credit: Tim Menard / USFWS. USFWS Mountain-Prairie, Wikimedia Commons

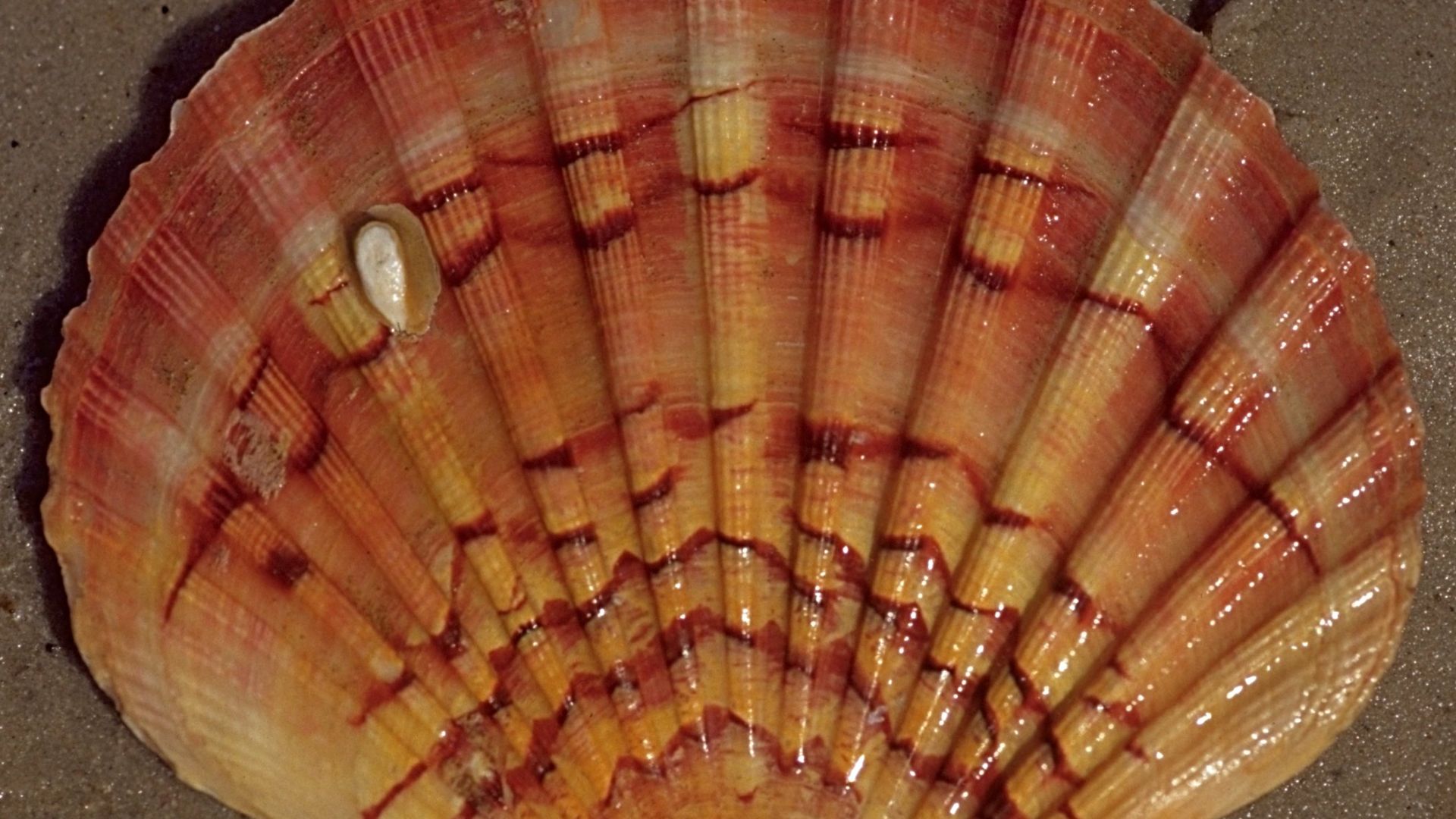

Scallops

Talk about the jet-propelled acrobats of the seafloor. Scallops are capable of rapid escape maneuvers that would impress any fighter pilot. They clap their shells together with explosive force, shooting backward through the water at speeds up to 15 body lengths per second.

Andreas Tille, Wikimedia Commons

Andreas Tille, Wikimedia Commons

Scallops (Cont.)

Such locomotion is powered by a single massive muscle (the part we eat) that can contract with incredible speed and force, allowing scallops to leap several feet off the bottom and glide through the water column. Unlike most bivalves, many scallop species never settle permanently.

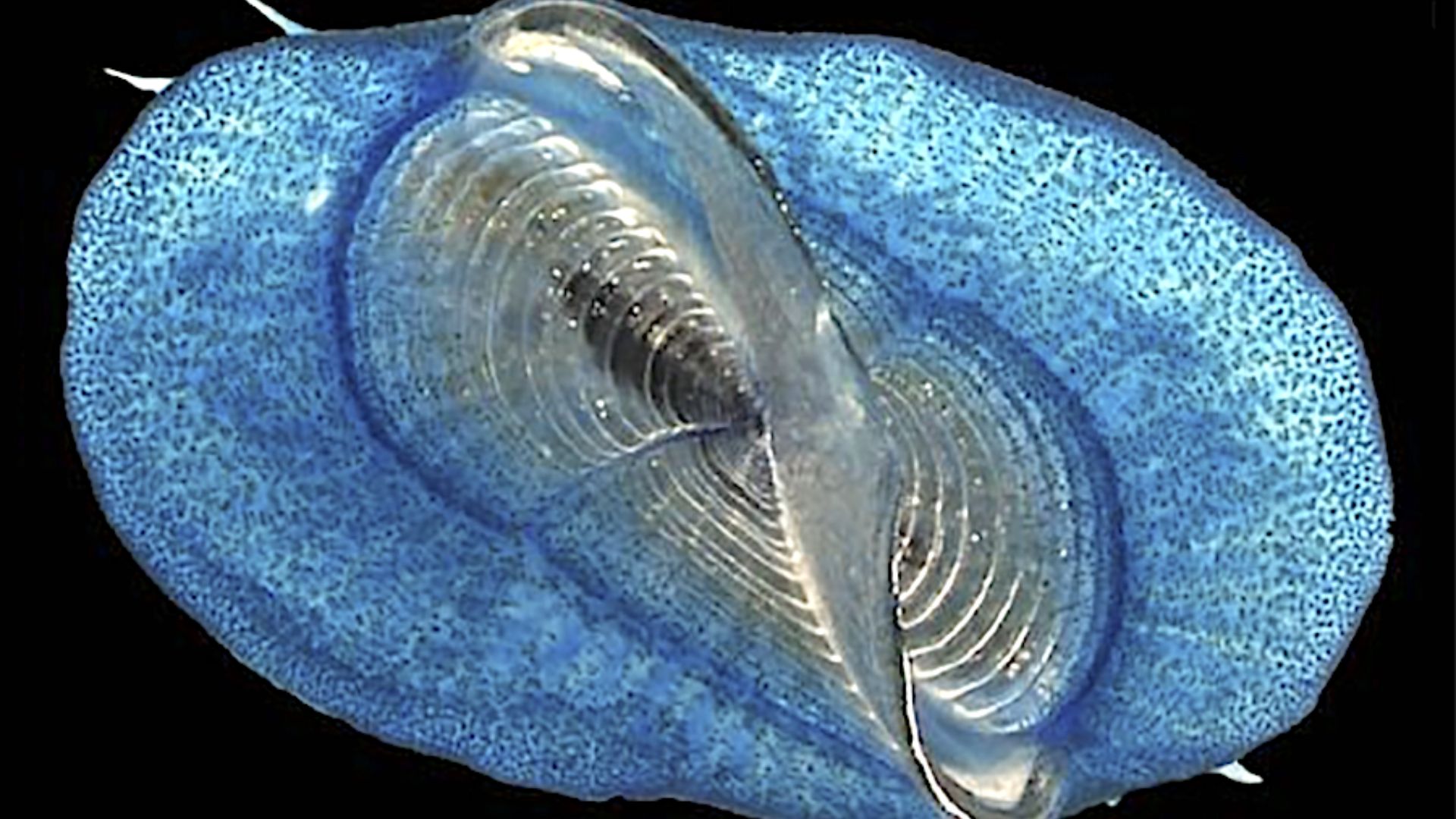

By-The-Wind Sailor

The By-the-Wind Sailor (scientific name: Velella velella) is a fascinating marine organism classified as a colonial hydrozoan. It has a flat, oval, deep blue to purple body, approximately 6 to 8 cm across, with a stiff, triangular sail that extends above the water surface.

Evan Baldonado, Wikimedia Commons

Evan Baldonado, Wikimedia Commons

By-The-Wind Sailor (Cont.)

This creature has trailing tentacles covered with stinging cells (nematocysts) that stun small planktonic prey such as fish larvae and zooplankton. The colony contains symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) that provide additional nutrition by photosynthesis. By-the-Wind Sailors are mostly passive drifters.

Rebecca R. Helm. Image by Denis Riek., Wikimedia Commons

Rebecca R. Helm. Image by Denis Riek., Wikimedia Commons

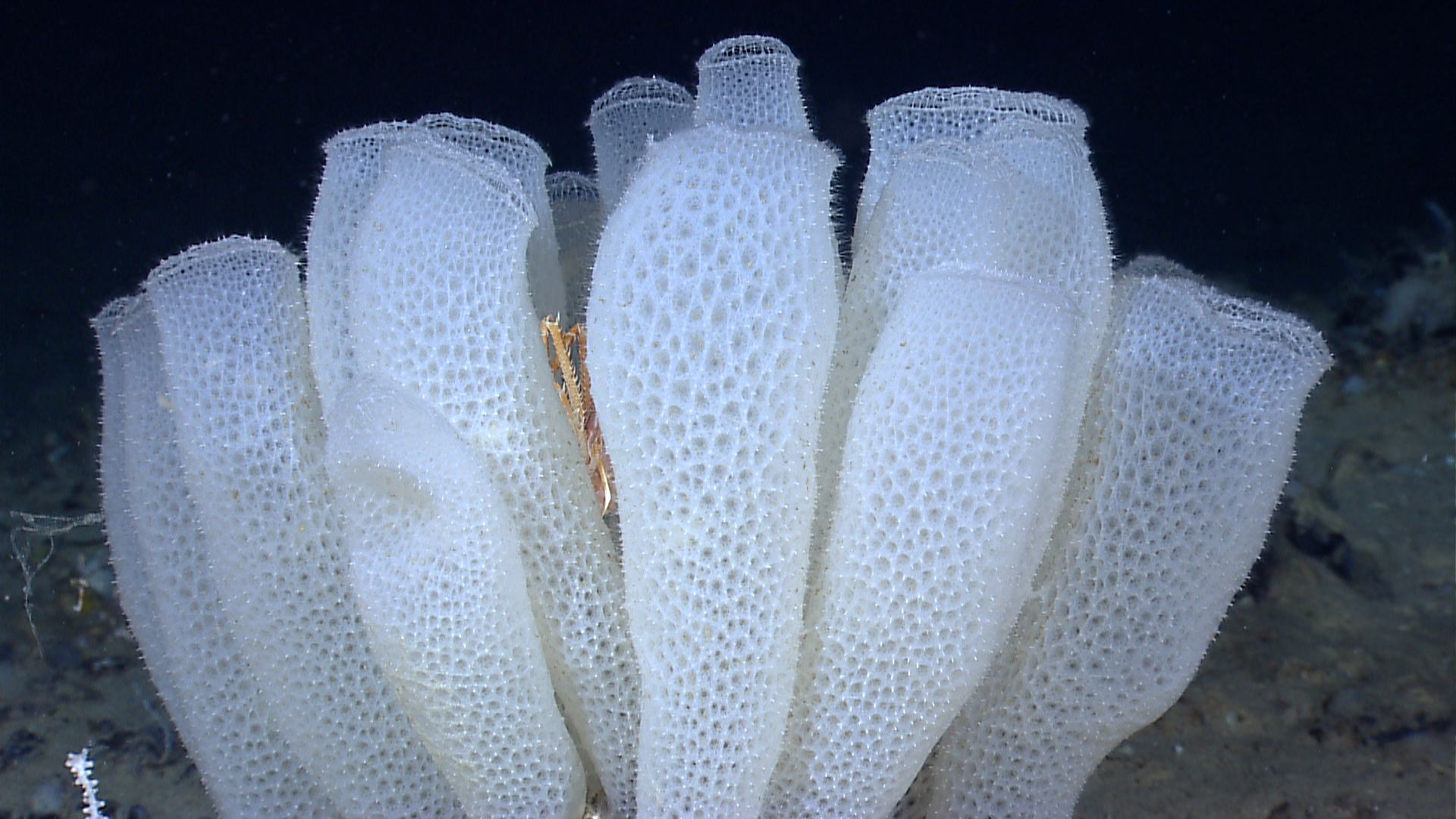

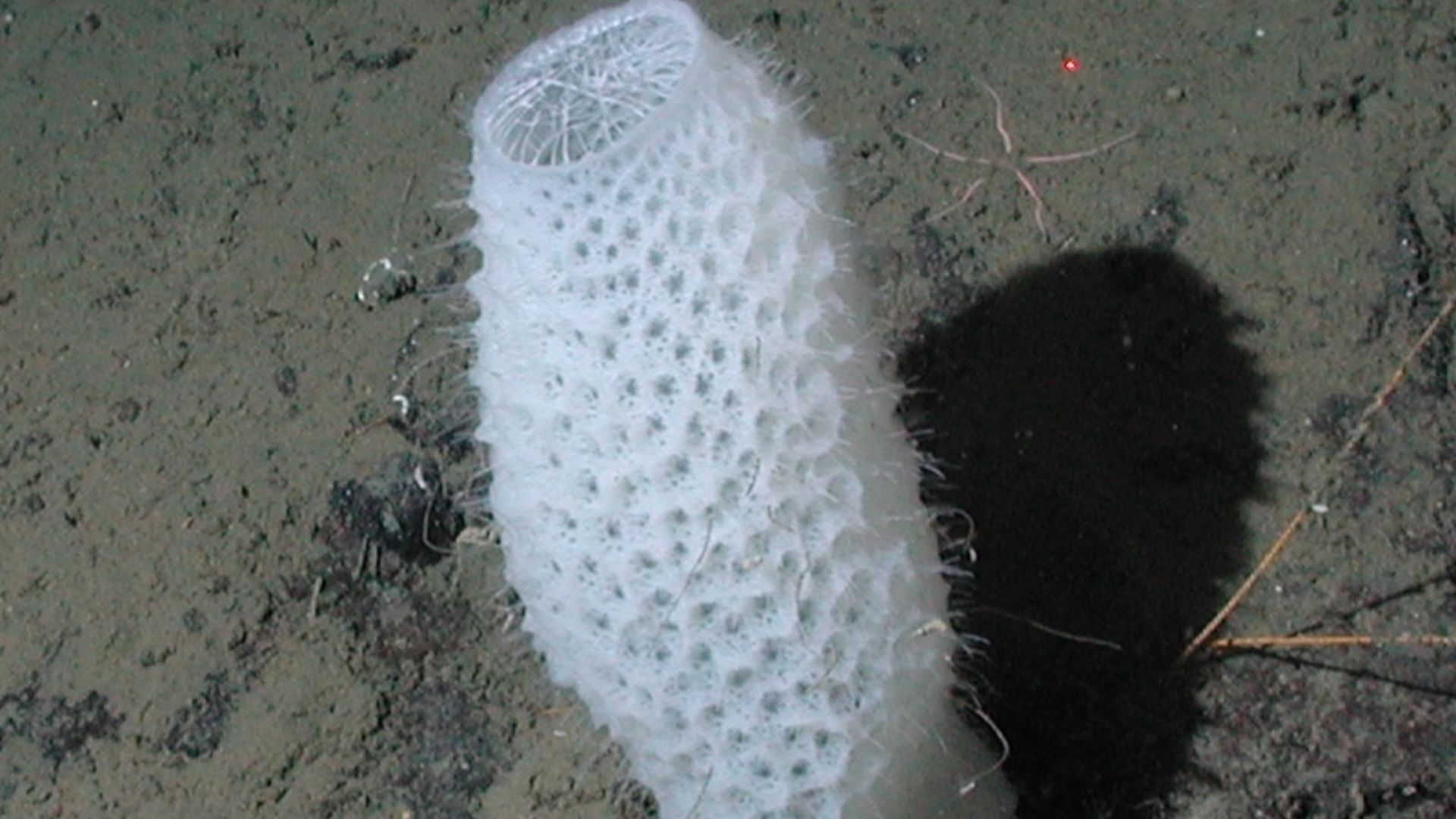

Venus Flower Basket

These deep-sea sponges construct their skeletons from pure silica, forming delicate lattice structures with spiral ridges and crossbeams that follow mathematical principles engineers are still trying to understand fully. Their fiber-optic spicules can transmit light more efficiently than human-made optical fibers.

NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Gulf of Mexico 2012 Expedition, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program, Gulf of Mexico 2012 Expedition, Wikimedia Commons

Venus Flower Basket (Cont.)

Living at depths of 1,000 to 6,000 feet in the Pacific Ocean, Venus Flower Baskets anchor themselves to soft sediments using root-like spicule tufts that can extend several inches into the seafloor. Despite their ethereal beauty and complex architecture, these sponges function without a nervous system.

NOAA/Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA/Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, Wikimedia Commons

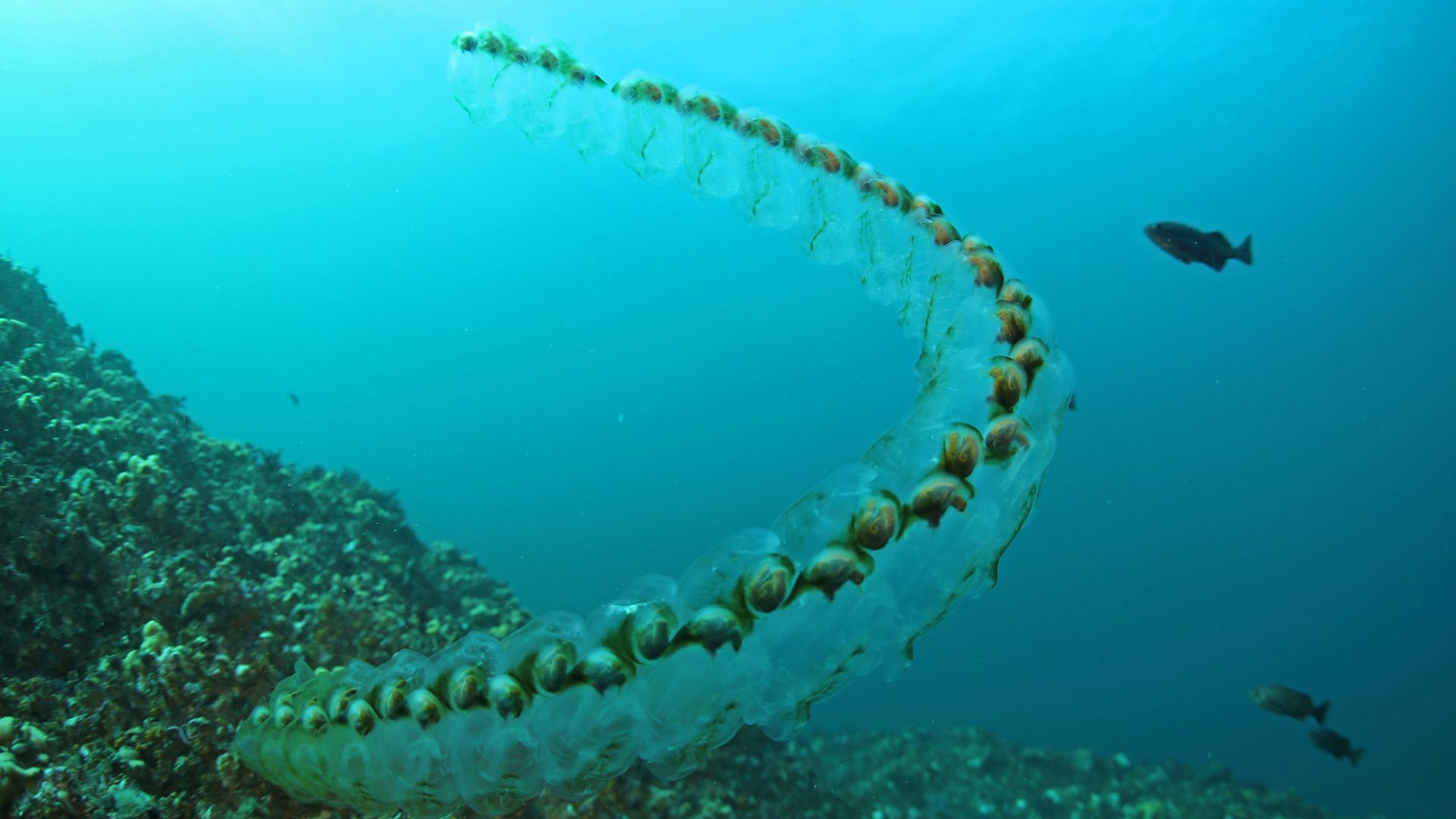

Salp

Salps are barrel-shaped, transparent marine animals belonging to the family Salpidae in the phylum Chordata and class Thaliacea. They live in most of the world's oceans, primarily in pelagic (open water) zones, and can be found singly or in long chains or colonies.

Peter Southwood, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Southwood, Wikimedia Commons

Salp (Cont.)

These creatures play an important ecological role by consuming phytoplankton and contributing to the ocean's carbon cycle through their carbon-rich fecal pellets, which sink and sequester carbon on the ocean floor. They can grow very rapidly, increasing their size by up to 10% per hour.

Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, Wikimedia Commons

Oregon Department of Fish & Wildlife, Wikimedia Commons