We all look at video every day. We watch videos on YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter. Some of us still even watch TV! Then, there's the video advertisements we see on the street and the video screens at Starbucks. Not to mention the videos we take on our phones. You get it, video is everywhere—but what is video? It's a massive part of our lives, but most people can't answer that question. For years, I know I sure couldn't.

Film vs. TV

I think, in general, most people understand how film cameras work. They take a lot of pictures every second and record them on a reel of film. When you play those pictures back at speed, our eye interprets them as a moving image. Basically, film cameras work like a really fancy flipbook. Pretty simple.

People used film to make the very first movies—in fact, we used film for movies until pretty recently. But film is not video. You go to the movies to see film, but at home on your TV, you’re watching video, and it’s a completely different process.

Mass Media

The problem with film was that there was no way to broadcast it into people’s homes. That’s where video came in. While film is completely physical, video is electronic. That means a studio can send a TV signal down a cable and anyone can tune in and watch. No movie theater needed.

To be honest, I never knew there was a difference between a film camera and a TV camera, but here we are. A TV camera doesn’t have reels of film spinning through it. Rather, for most of the history of television, instead of film, TV cameras used ray guns. Seriously.

Techo-Babble

Remember how easily I described how a film camera works? Well, unfortunately, video cameras are a little more complicated. I’ll try to keep it as simple as possible—bear with me:

Video all started with the cathode ray tube. Remember those huge old bulky CRT TVs? That’s what I’m talking about here. On the one end, the camera shoots a beam of electrons across an image. This converts the image—let's say, the set of a sitcom—into an electric signal. Now, a cathode ray tube can shoot electrons fast, so it takes another image, and another, and soon the TV camera has converted an entire scene into a signal.

That signal can now be broadcast, either through radio waves (the old bunny ears on your TV) or a cable, into people’s homes. In those homes would be a TV with its own cathode ray tube. This time, the CRT takes the signal, fires its own electrons at a phosphorescent screen, and makes the same image appear. Zip, zap, zop.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: that sounds insanely complicated. But, since we can’t all go to the movie theater every night, that’s what it took.

From Tape to HDMI

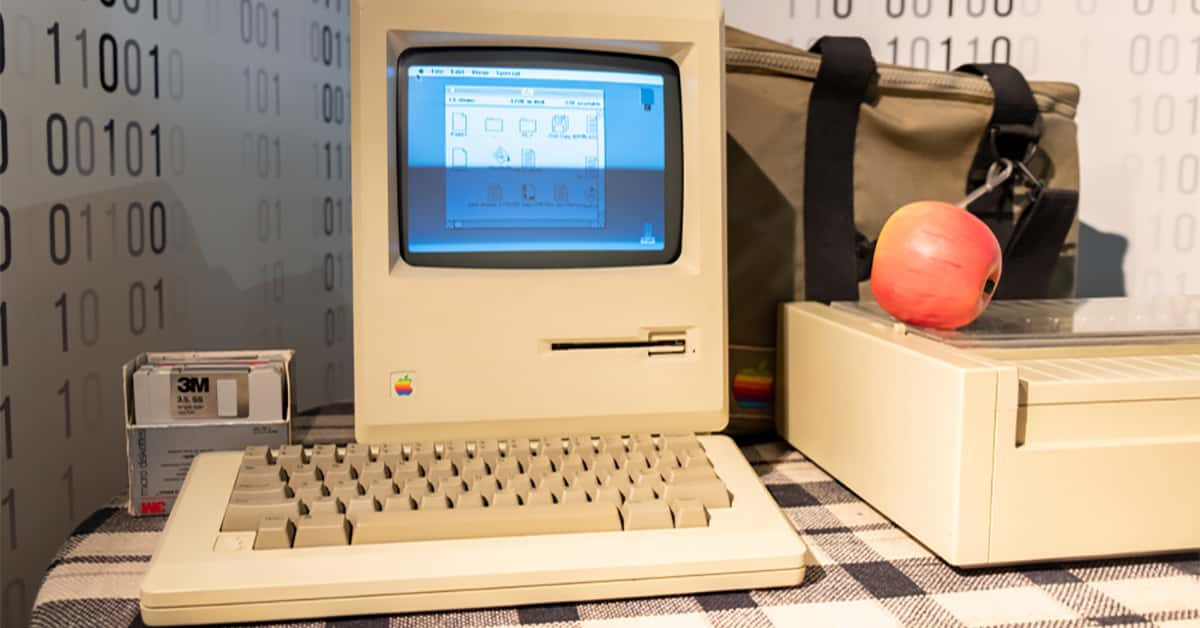

Early TV had one serious disadvantage over film—we couldn’t record it. You could shoot a movie, copy the reels, then ship it across the country to be viewed as much as you like. Not so with a video signal. For years, every single thing on TV was completely live, the signal sent straight from the camera to your screen. If you were watching a movie on TV, it was literally just coming from a video camera pointed at a movie screen.

Fortunately, video technology kept getting better. First, videotape allowed us to record video broadcasts. Next, something called “digital” video appeared, and it eventually let us finally throw away our bulky old CRTs in favor of sleek LCD screens with high-def HDMI inputs. Almost every video we see today is digital. Gone is the simplicity of the electron beams and the phosphorescent screens, but the idea’s the same. Take an image, convert it into a signal, and send it to people’s screens. It’s just now, we’ve got a few more screens than we used to.