A prolific yet haunting body of work that showed an exceptional eye and talent, but went unappreciated. A short and tragic life followed by an avalanche of posthumous appreciation. It all sounds like an overused trope, but after learning about Francesca Woodman and looking at the undeniable beauty of her work, it’s easy to see why people remain so fascinated with her, even though almost four decades have passed since her untimely death.

Francesca Woodman Editorial

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Woman

Woodman was, essentially, born to be an artist. Both her parents, George and Betty, were artists, and her older brother is now a professor of art at the University of Cincinnati. Her upbringing was privileged—her family spent many summers in Italy, and when she was in second grade she spent a year there. While she went to public school in her early years, when it was time to enter high school she was enrolled at a private boarding school in Massachusetts, Abbot Academy, that was known for its emphasis on art education.

It was at Abbot that Woodman began to take photographs, a hobby that would soon turn into her practice. Although she eventually transferred out of Abbot to return to public school in Boulder, Colorado, she would continue taking photographs until her death. After she graduated high school, she was accepted at the prestigious Rhode Island School of Design. This period included a one-year exchange in Italy, where her childhoods spent there and her grasp of the language made her popular among Italian artists and intellectuals.

Reality Bites

Woodman graduated from RISD in 1978 and went to New York City to carve out a career for herself as a photographer the following year. After years of attention and praise at school, it must have been a difficult go of it for Woodman. Every small victory was contrasted with some form of rejection, either professional or otherwise. The same year she received a residency at the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire, she attempted to break into the world of fashion photography in New York City to no avail.

When Woodman returned home from MacDowell, it was clear that something was wrong with her. Her relationship with a glass art student had ended and her career was stagnant. She was only 22, but try telling any young girl, let alone one suffering from depression, that things will eventually get better. In the autumn of 1980, Woodman attempted to take her own life. She survived, and in the aftermath, ended up back with her parents.

Despair in Art

Despite the despair that Woodman was feeling, she continued taking photographs the entire time—her family still has over 10,000 negatives that she took between 1972 and 1980. Generally, of the work that has been shown to the public, a few common aspects are woven throughout that have become characteristic of her oeuvre. Most of Woodman’s work was made in a small format, requiring the viewer to increase their proximity to the work, creating a sense of intimacy, and it’s mostly in black and white.

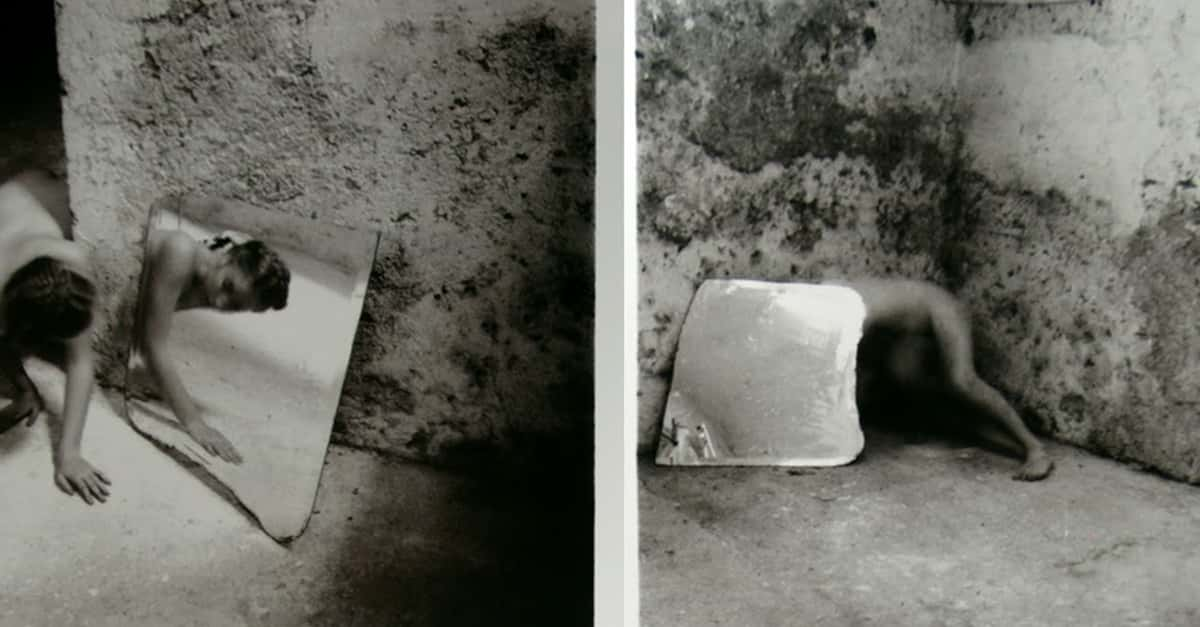

What many find truly striking is Woodman’s settings and subject matter. Many of her photographs are taken inside abandoned or derelict spaces, mostly domestic—apartments with peeling wallpaper; broken mirrors on the floor; or light shining in through large windows only to illuminate dusty, run-down interiors. Woodman often used a long exposure, leaving her settings crisp and still, while her human subject matter appears blurred, at times signifying motions, at others, resembling deformations.

As for that subject matter: female bodies appearing disembodied, with parts obscured behind the aforementioned peeling wallpaper, or feet peeking into frame from without. Completely blurred, or with eyes hidden, or peering out from behind an object. The poses are uncanny: in one, the model dangles from a doorframe by her hands, her face hidden by her arm, a sort-of nooseless hanging victim. Crouched behind a fireplace mantelpiece leaning against a wall, with legs straddling the lintels. Nudity, animals (dead or alive), dolls, and allusions to death are all recurring motifs.

Some Disordered Interior Geometries

Woodman’s photographs have a distinctly surreal quality to them. They’re haunting in more than one sense of the word: so sublimely beautiful that they’re unforgettable, while also simultaneously embodying an eerie, ghostly quality. Aside from Woodman’s collections of photographs, she also produced video work (which was only ever exhibited decades after her death), and a number of artist’s books.

Only one of these, Some Disordered Interior Geometries, was published during her lifetime. For it, Woodman attached some of her photographs to pages from an Italian geometry exercise book, adding notes here and there. The pictures create a stark contrast against the geometric equations, with images of soft, blurred bodies posed off-kilter seeming to fly into the face of everything the ancient fathers of mathematics appreciated.

On Becoming an Angel

The themes of disappearance and disembodiment that filled Woodman’s work sadly connected to her personal life and her mental state. After her late 1980 suicide attempt, Woodman had been in therapy, and one of her friends even wrote that things had been improving for the young artist. However, according to Woodman’s father, things turned around yet again when she was denied funding from the National Endowment for the Arts. Sadly, he suspects that this was one of the primary reasons why Francesca Woodman tried to die again on January 19, 1981. Woodman was at a loft on the East Side when she jumped out of a window. This time, the suicide attempt was successful. She was just 22 years old.

In the years following her death, Woodman received the critical validation and audience appreciation for her photography that escaped her in her lifetime. It took a few years after her death for word to spread about her work, but since 1986, there have steadily been exhibitions and publications showcasing Woodman’s output. Her family has worked to guard her body of work, keeping the aforementioned 10,000 negatives and maintaining an archive of over 800 photographs, only about 120 of which have been published. This ensures that, despite her untimely death, that her work will live on forever—and always with the captive audience that she so desired.