When I first learned about the performance artist Marina Abramović, a flutter of excitement flared in the pit of my stomach. Her work was daring and dangerous and so far removed from what I’d been taught to think of as “art." It was unlike anything I’d ever seen before.

Abramović was all about endurance and duration, and her work was intensely controversial. Oftentimes, she even put her life on the line.

Facing Mortality

In one of her most famous pieces Rhythm 0, Abramović involved the audience by giving them some simple instructions:

“Instructions. There are 72 objects on the table that one can use on me as desired. Performance. I am the object. During this period I take full responsibility. Duration: 6 hours (8 pm - 2 am).”

This free-for-all had a shocking effect. In the beginning, people chose the kinder objects to interact with Abramović. But soon, people picked up scissors and cut off her clothes, others touched her intimately, and one man even held a loaded weapon to her head.

When the performance was finally over, the viewers ran away. They couldn’t confront the horror of what they had done. Abramović left the scene in shambles—bleeding, almost naked, and totally violated. But in spite of all this, the performance was a resounding success. She staged the fear of mortality and conquered it.

Wikimedia Commons // Manfred Werner / Tsui

Wikimedia Commons // Manfred Werner / Tsui

Learning To Trust

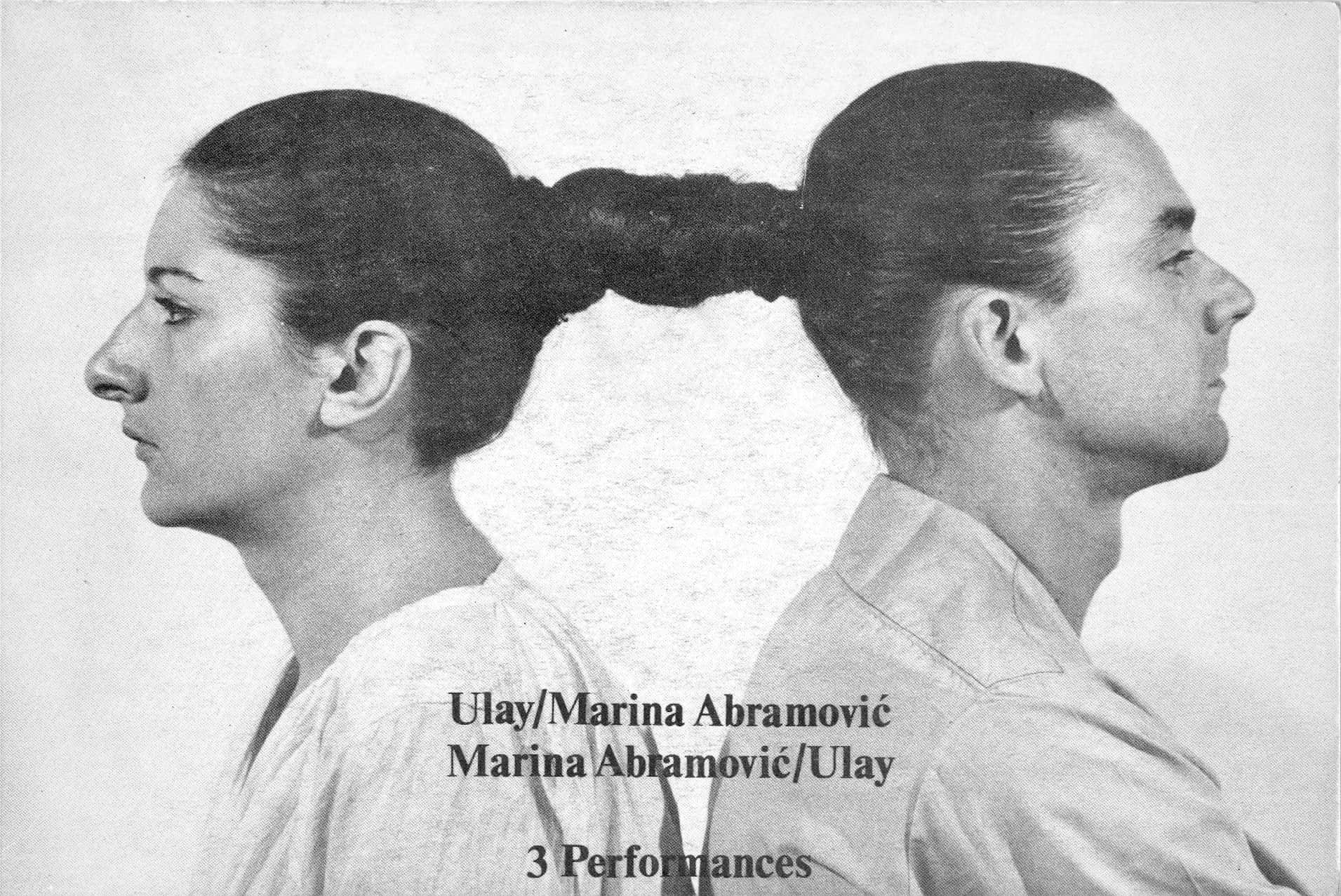

But Abramović’s fascination with pain wasn’t static. When she moved to Amsterdam in 1976, something happened that changed everything—she fell in love with Uwe Laysiepen, who went by the name Ulay. Now, just because she got hit with the warm-and-fuzzies didn’t mean that she gave up on life-threatening art. Going forward, she simply had a partner to collaborate with.

Ulay was also a performance artist, and he too shared Abramović’s artistic vision. But with their love in mind, her focus shifted away from the aggression of her earlier work and became more reflective of their deep trust. In one of my favorite pieces—a terrifying four-minute video that hurts to look at—Abramović places her life in Ulay’s hands.

In Rest Energy, the couple stands face-to-face, a bow and arrow stretched between them. Abramović holds the bow while Ulay holds the end of the arrow pointed straight at her heart. This is where the trust comes in. She trusts him not to let go. It’s wild.

Pushing The Boundaries

For the next 12 years, Abramović and Ulay traveled with one another, performing their work. They became so inseparable that they referred to themselves as a “two-headed body.”

In their piece Breathing In/Breathing Out, the two of them explore the notion of exchanging life with another person—how this exchange can end in destruction. Through an intimate gesture that looks like a kiss, they breathe into each other’s mouths for 17 minutes until the lack of oxygen causes them to pass out.

In Relation In Time, the couple sits back-to-back for 16 hours, their heads tied together. Conversely, another performance arranges them face-to-face—screaming at one another until Ulay eventually folds.

When I first saw these pieces projected on large screens, I was confused. In my experience, art hung on a wall. It was usually beautiful, sometimes abstract, but always contained. Abramović’s work was messy, raw, and definitely visceral. Just knowing that art could be challenging fired me up. I wasn’t sure if I liked it, but I wanted to know more.

Saying Goodbye

The most compelling thing about Abramović is that despite the darkness in her work, she also has pieces that pull on your freakin’ heartstrings.

In 1988, the couple began their epic piece, The Lovers. By this time, both Abramović and Ulay’s relationship had weakened through a number of affairs on both sides. Due to their growing unhappiness, they decided to transform a piece originally intended to mark their marriage into a journey toward goodbye.

The Lovers was a massive undertaking—both spiritually and physically. Each partner began the piece on opposite ends of the Great Wall of China. Abramović set off from the Yellow Sea and Ulay began in the Gobi Desert. The end goal? Walking toward one another and meeting in the middle. Then, they would say their last goodbyes and never see each other again. Super dramatic and super romantic.

According to Abramović, "We needed a certain form of ending, after this huge distance walking towards each other. It is very human. It is in a way more dramatic, more like a film ending...Because in the end, you are really alone, whatever you do."

The journey toward separation was long and arduous. It took them 90 days to complete and they each covered a spectacular distance of around 2,000 km. By the time they met, they were ready to part ways forever.

A Moment Of Connection

But this wasn’t the end of Abramović and Ulay’s story. In 2010, the MoMA had a retrospective exhibit of Abramović’s work where she staged yet another stunning piece, The Artist Is Present. This time, there was no blood, no risk, no nudity. It was extremely simple and overwhelmingly effective.

Abramović sat at a table for eight hours a day. During this time, she invited members of the audience to sit in the chair opposite her and hold her gaze. They weren’t allowed to engage with her or touch her—just look. The reactions of the participants varied, but many were moved to tears.

On opening night, Abramović was in for a heart-rending surprise. After not seeing him for 22 years, she looked up to see Ulay sitting across from her. The emotions were palpable. The tears were TOO real. And for a moment, she broke her performance, reached across the table, and took his hands into hers.

The Artist Is Present, YouTube

The Artist Is Present, YouTube

The Artist Is Present is an endurance piece, but for me, it’s all about the need for human connection. Abramović stared into the eyes of hundreds of strangers and shared real moments of intimacy...And then her ex-lover showed up and everyone ended up crying.

You can’t really attend art school without learning about conceptual art, and you certainly can’t leave without discovering the genius of Marina Abramović. At first, it’s really hard. You want to hate it—rail against it. But then you realize that art can be an idea, that the body is expansive, and that Marina Abramović truly deserves the title “the grandmother of performance art.”