Camp is having a moment. Recently, the Met Gala selected the aesthetic as its theme for its annual fashion extravaganza. Drag queens are almost mainstream, with RuPaul’s Drag Race moving to VH1. Indie theaters regularly screen past flops, with a Showgirls viewing party so popular that its enthusiastic audience rivals fans of The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

The criminally under-watched comedy The Other Two even centered an entire episode on camp. When a Bieber-lite pop star named ChaseDreams releases a mawkish single called “My Brother’s Gay and That’s Okay,” a group of PR executives track audience response in real time. Listeners move from viciously attacking the faux-woke video, wherein Chase outs his brother Cary, to celebrating its inadvertent parody of preachy videos like Macklemore’s “Same Love.”

ChaseDreams’ godawful song gets to the paradox at the heart of camp. Is an overblown piece of art so awful that it becomes self-reflexive and enters the chic terrain of camp—or are things simpler? Is an over-the-top song or movie just plain bad?

Flickr From the Camp: Notes on Fashion exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Flickr From the Camp: Notes on Fashion exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

Tacky Tenderness

This fundamental question takes us back to camp’s strange roots. Long before John Waters and Divine revolutionized camp into a self-aware, grotesque, joyous aesthetic, the literary critic Susan Sontag wrote about a gentler breed of camp taste. As she put it in a 1964 essay, “Camp is a tender feeling.”

But in 2019, few people would describe John Waters’ bombastic oeuvre with such a soft word. From tenderness to tackiness, camp evolved by augmenting one crucial element: intention.

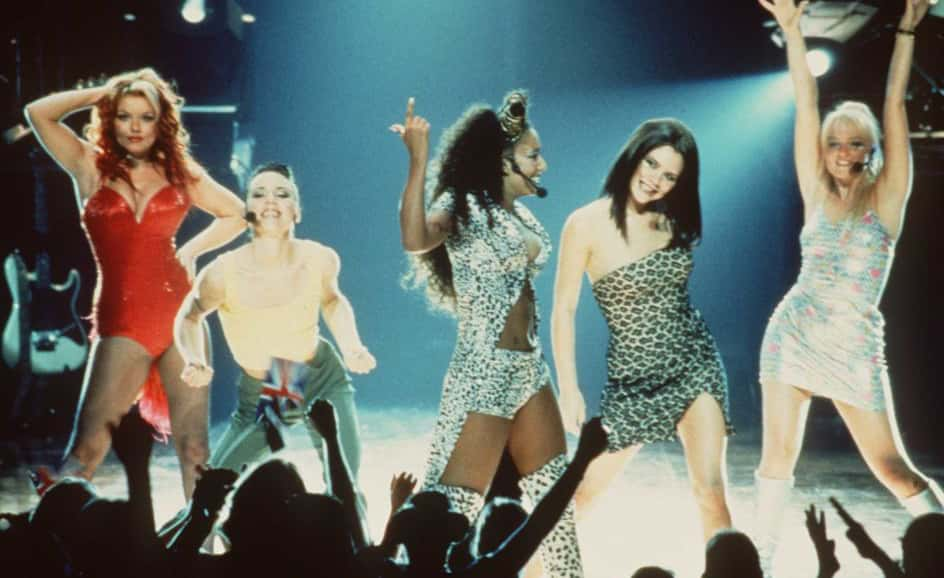

Nowadays, directors can choose to make campy movies. Some modern examples are Cry-Baby, Spice World, and the glorious But I’m a Cheerleader, which puns on its aesthetic by being set at a literal camp. But back in the day, that wasn’t possible. In fact, these movies often emulate films that didn’t mean to be campy at all.

Getty Images Spice World

Getty Images Spice World

Epic Fail

In the 1940s and 1950s, camp couldn’t be intended because camp hadn’t been identified yet. Movies we now call campy were dismissed as failed melodrama. Before camp swept in and rescued its overwrought damsels, movies like Glen or Glenda and Johnny Guitar were just schlocky.

These movies meant to be serious. They wanted to evoke the kind of gravitas that signals high art about the human condition but they overdid it and become farce. See the unintentional masterpiece that is What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?

In a notorious scene, Jane gives Blanche her dead pet parakeet for lunch (don’t ask). They have what is supposed to be a dramatic confrontation that culminates in the most sublime line in cinema history, “BUT YEH ARE, BLANCHE. BUT YEH ARE IN THAT CHAIR.”

RuPaul Parody of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane on Rupaul's Drag Race?

RuPaul Parody of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane on Rupaul's Drag Race?

The scene is so over the top that it collapses under itself. It tries to be profound but goes too far and ends up being outrageous. Despite this failure—or rather, because of this failure—this moment is beloved, especially by the gay community (see Drag Race‘s homage).

Joyful Stumbles

This style of unintentional camp flourished in the 1940s and 1950s though you can find its descendants throughout the 20th and 21st centuries with films like Showgirls and The Room. While many campy movies embrace their own silliness—Barbarella, Moonraker, and Flash Gordon come to mind—I’m interested in accidental camp.

Accidental camp may not be intended but it is chosen. It’s what happens when an audience decides that an awful movie is wonderful instead. Movie-watchers have to see something overblown—something that fails to be meaningful—and respond not with derision, but with tenderness.

Movies in Search of a Gentle Viewer

Modern camp already knows it’s camp—it has a home in the world of genres. But old-school camp didn’t have that privilege. These movies were misfits and losers. They tried to be high-brow and failed spectacularly.

Whatever, you could say, lots of movies fail. What makes these special? The answer is a little strange because the answer isn’t the movies themselves. It’s the audience.

Getty Images Showgirls

Getty Images Showgirls

There’s something remarkable in how the audience not only forgives a cringe-inducing, should-be tragedy but accommodates its unintentional triumphs. Instead of fixating on missteps, camp embraces exhilarating, gung-ho, excess. It’s game. Camp goes all in, it bets big, and it loses tremendously—at first.

A special kind of audience saves camp by celebrating failure with such giddy intensity that they transform a benchwarmer into an underdog champion. This kind of camp is exceptional because it’s relational: It only happens when an audience goes along with a bizarre movie and sees what it has to offer. It only happens when an audience decides to be generous.

All Hail Sontag, Namer of Sensibilities

Sontag says it better. She writes that:

“Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation—not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy. It only seems like malice, cynicism. (Or, if it is cynicism, it’s not a ruthless but a sweet cynicism.) Camp taste doesn’t propose that it is in bad taste to be serious; it doesn’t sneer at someone who succeeds in being seriously dramatic. What it does is to find the success in certain passionate failures.”

She argues that as consumers of art and culture, viewers can change the sensibility and status of the media that they watch and read. The audience can choose to be kind and find something worth appreciating in a “passionate failure.”

Sontag concludes her essay with a rallying cry. It’s normal to think of failure as something to be mocked or punished, but on the other hand, failure is human, failure is normal, and failure will come for us all. We can choose to orient ourselves otherwise.

In her words, “Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of ‘character.’ Camp taste identifies with what it is enjoying. People who share this sensibility are not laughing at the thing they label as “a camp,” they’re enjoying it. Camp is a tender feeling.”

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17