Unintended Consequences

In 1958, the Chinese Communist Party, led by Chairman Mao, launched a campaign to bring the country into a better and brighter future. While the motive behind this campaign may have been born out of good intentions, it resulted in a disaster beyond anything they had imagined.

The Chinese Communist Party

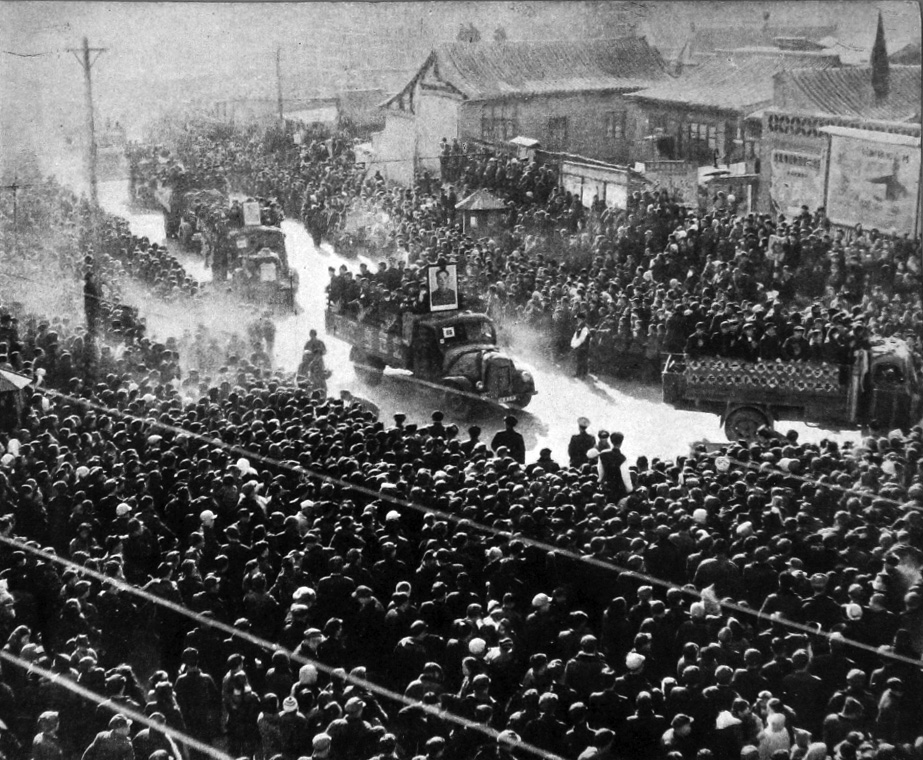

Since the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Communist Party of China has governed the country, initially led by the position of Chairman of the Central Committee. As the CPC’s first Chairman, Mao Zedong introduced many economic and social reforms, including one of the party’s most notorious campaigns.

Chen Zhengqing, Wikimedia Commons

Chen Zhengqing, Wikimedia Commons

The Great Leap Forward

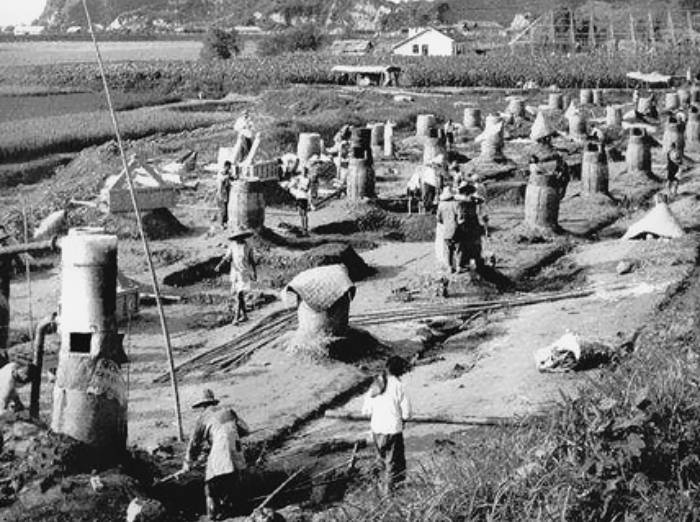

Beginning in 1958, Mao devised the Great Leap Forward campaign to further the CPC’s industrialization goals. This campaign, which included many projects, aimed to utilize China’s manpower to advance industrial and agricultural progress instead of solely relying on machinery.

Zhao Yangshan, Wikimedia Commons

Zhao Yangshan, Wikimedia Commons

Large Reform

By and large, the ideas behind the Great Leap Forward were to focus on the contributions of the peasantry on the path to socialism. As such, those in power assigned less significance to intellectuals and scientific experts, allowing those of lower social statuses to contribute more. The government also provided many official ways of involvement.

Wei Dezhong, Wikimedia Commons

Wei Dezhong, Wikimedia Commons

Many Dedicated Projects

As a core ideal behind the Great Leap Forward, Mao strived to organize China’s citizens to use their manpower more efficiently. His policies framed things like steel production and farming as communal efforts, with the former becoming more common as a backyard practice. Regarding the field of agriculture, Mao also had some changes in mind.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Eight-Point Charter of Agriculture

Mao centered much of the country’s progress on its agricultural output, and to do so, he implemented several new policies. One such policy was the 1958 Eight-Point Charter of Agriculture, which contained basic improvements such as water conservancy and plant protection. The latter would lead to some of the more disastrous effects of his campaign.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

There Was Less Food

Although Mao intended these changes to lead to prosperity, the results were far from it. China was already facing agricultural issues, but many of Mao’s newly introduced practices only worsened food production. Of course, possibly the biggest culprit was the infamous campaign in question.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Four Pests Campaign

Commencing early in the Great Leap Forward, the Four Pests Campaign called for the immediate elimination of four animals thought as blights against the modern world. This goal’s roots were in the idea that these four creatures, along with the public's general hygiene, were responsible for China's agricultural and health problems.

Red Cross and the Health Propaganda Office, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Red Cross and the Health Propaganda Office, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cleanliness Was A Priority

Mao’s vision for China’s future was to transform the country plagued by overpopulation and economic imbalance into a socialist utopia. In his eyes, however, this wasn’t possible without prioritizing hygiene and cleanliness, although this was only one motive behind the campaign.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Man Vs Nature

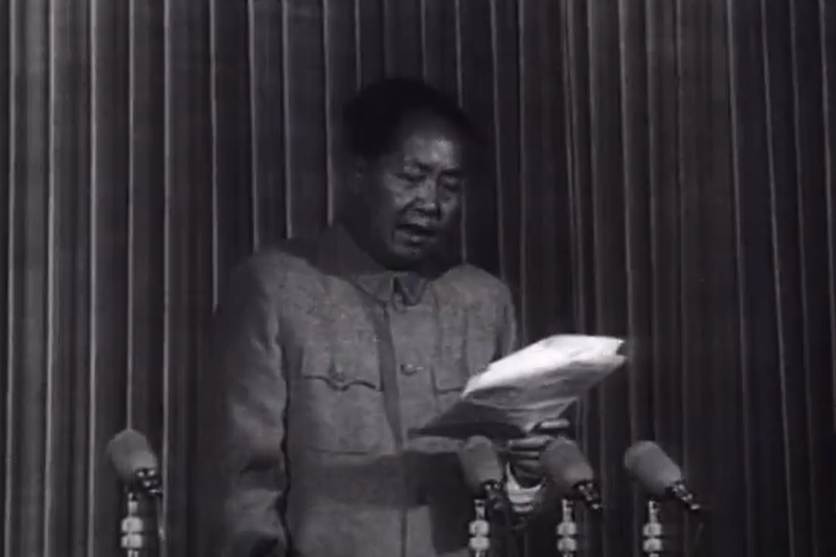

One specific slogan for the Four Pests Campaign was "Man Must Conquer Nature". This promoted the idea that to achieve their utopia, China’s citizens would have to overpower the nature around them and use it to their advantage. This was a very different belief from what had previously been practiced.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Leaving The Past Behind

China severely deviated from some of its oldest belief systems during the Four Pests Campaign. Many had previously practiced the philosophy of Taoism, which emphasized a harmonious coexistence between humanity and nature. However, the campaign sought to upend that, starting with two specific bugs.

Shanghai Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Shanghai Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Two Dangerous Insects

Seen as extreme threats to Chinese civilization, the campaign targeted two insects for elimination. These were mosquitoes and flies, as both frequently bore diseases, with the former being specifically dangerous for its transmission of malaria. Flies were also present in rural and urban areas, making them difficult to combat.

More Disease Carriers

The third “pest” that the campaign targeted had an association with plagues since the Dark Ages. Rats were disease transmitters, and beyond that, they were seen as significant threats to the grain industry. This made them an obstacle in Mao’s goal of industrialized agriculture, much like the final “pest”.

A Threat To Agriculture

The fourth and final animal to be put on Mao’s chopping block was a bit of an outlier. Believed to be a major reason for China’s failing agriculture, sparrows joined the Four Pests Campaign. They were not disease carriers but their grain consumption was thought to be the leading cause of food shortages.

Andreas Trepte, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

Andreas Trepte, CC BY-SA 2.5, Wikimedia Commons

They Were Very Convincing

Mao and the CPC relied heavily on propaganda to get everyone on board with the campaign. They used patriotism as a primary motivator, glorifying the destruction of these pests as a heroic deed for the country, much like propaganda used toward army recruitment. However, something was missing from their justification.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Little To No Concrete Basis

When presenting the Four Pests Campaign to the public, Mao overlooked a basic factor in their reasoning due to the party’s anti-intellectualism. In all the propaganda, there were no hints of scientific backing for the plan, despite the party insisting that Mao’s Eight-Point Charter was scientifically based.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

It Would Affect The Future

In his propaganda, Mao weaponized people’s fear and hope for a brighter future. Although there was little real science or concrete evidence, the CPC promised that if everyone did their part in eliminating these pests, the resulting prosperity would last hundreds of years. As it happened, this widespread propaganda worked.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Everyone Was Involved

In keeping with the core ideals of the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s plan hinged on getting everybody in China to participate in this campaign. It wasn’t just men and women taking steps to eliminate the pests, but the children too. In fact, he called on everyone older than five to join the cause.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Branding Was Everything

It’s important to note that the CPC’s messaging hadn’t started with the Four Pests Campaign. Previous examples of propaganda had primed the public to go along with these plans, framing Mao’s party as the ones to take charge—and through that, the only path to a utopia.

All The Demographics

Since Mao wanted everyone to do their part, he aimed much of the propaganda at children too. This included posters intentionally made to be visually striking, featuring children destroying each of the pests. Of course, the CPC also ensured everyone knew how to eliminate the pests.

Bi Cheng, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bi Cheng, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Fly Swatters

To exterminate the threat of flies in China, the CPC implemented various techniques, such as using insecticides on known breeding grounds and installing traps in public spaces. Beyond this, the government took a more self-sustaining approach and educated the masses on waste disposal and hygiene.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Mosquito Repellant

The CPC used similar strategies as they had for flies to exterminate the mosquitoes, targeting their breeding grounds. While insecticides were still heavily relied on, there was a push to eradicate as much stagnant water as possible. Of course, there were more than just insects to worry about.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Exterminating The Rats

In addition to deploying rat poison and traps throughout China, the government encouraged the public to use some of the more natural resources on hand. As such, cats were set loose upon the large population of rats, using their natural hunting proficiency. However, the final pest was met with a more hands-on approach.

The Near-Eradication Of Sparrows

The CPC implemented multiple strategies to match the perceived threat of sparrows to China’s grain storage. Nests were routinely destroyed, and citizens were urged to deter sparrows from roosting by making loud noises. Beyond that, since sparrows didn’t pose a threat of transmitting diseases to humans, it was common to eliminate them by hand.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

School Trips

When it came to exterminating sparrows, it was considered a civic duty and operated as a coordinated country-wide effort. As a regular part of the school day, children and their teachers would leave at a specified time to find sparrows and exterminate them together. This kind of mobilization was more than just a suggestion, though.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Two-Sided Approach

For Mao, asking China’s citizens to help out and hoping for the best wasn’t enough. To ensure their cooperation, the government used manipulation tactics of encouragement and coercion, drawing on both patriotism and fear. At the same time, those who participated enough were certainly compensated.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

They Were Rewarded

Rather than relying only on coercion, Mao’s government used incentives to further the public's positive mindset. Schools and organized groups from workplaces or government agencies received awards for having high elimination numbers. Needless to say, they exceeded expectations.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

The Final Count

By the time the Four Pests Campaign came to an end in 1961, the number of exterminated pests had reached incredible heights. All in all, the campaign was responsible for culling 24 million pounds of mosquitoes, 220 million pounds of flies, 1.5 billion rats, and 1 billion sparrows.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

It Was A Success

Overall, the campaign was successful in one of its major goals to reduce the spread of diseases. At its core, in the efforts to exterminate the four pests, Mao’s government had certainly completed their objective. However, this wasn’t the win they thought it was.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

It Messed Everything Up

Although there were noticeable benefits to eliminating flies, mosquitoes, and rats, the depletion of the sparrow population had only negative effects. With little to no research done beforehand, the government hadn’t foreseen the major ecological ramifications that such a severe extermination would cause.

Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Rhododendrites, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

It Created More Pests

Without the presence of sparrows in China, there was room for a much more serious agricultural threat to thrive. Missing their natural predators, the locust population surged and overwhelmed China’s crops. To make matters worse, the people discovered this revelation only too late.

They Were Wrong

A year before the campaign ended, the foolishness of Mao’s battle against sparrows became apparent. Those at China’s Academy of Sciences examined the stomach contents of several deceased sparrows and found they contained mostly insects. This was in contradiction to Mao’s assertion that their grain consumption was the cause of food shortages.

N509FZ, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

N509FZ, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

An Unseen Disaster

In Mao’s attempts to cull the population of all the creatures he deemed threats to China’s future, he inadvertently paved the way for much graver consequences. Following the sparrow extermination and locust surge, a catastrophe of never-before-seen magnitude ensued.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

They Lost Everything

The rapid growth of the locust population affected China’s crops and quickly translated into a large-scale crisis. From 1958 to 1962, the country endured what would become known as the largest famine in history, at least when considering the loss of life.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

There Were Other Factors

Even without the massive famine, Mao’s government had placed China’s agricultural industry on a path to inevitable failure. Including reforms such as taking farmers out of their fields and moving them to industrial work, many of his policies only weakened the country’s food supply.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

A High Toll

Instead of the promised utopia and prosperity for generations to come, the Four Pests Campaign led only to widespread suffering. In the end, the Great Chinese Famine led to the demise of 20 to 30 million people, leaving little room to deny the cataclysmic mistake Mao had made.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

They Came To Their Senses

Fortunately, Mao’s government wasn’t ignorant of their contributions to the famine. With the change from sparrows to bed bugs and the end of the Great Leap Forward, Mao acknowledged the negative effects wrought, as there was no denying the suffering taking place. It was too late to alter their course, but they still tried.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

They Changed Targets

By 1960, even though the effects had already been cemented, Mao’s government ended their efforts to exterminate the sparrows. Hoping to continue the plan, they replaced sparrows with bed bugs as a target for elimination. Of course, the campaign itself was on its last legs.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

It Finally Ended

After causing much more harm than any good they intended, Mao’s government abandoned their cause. In 1962, the Great Leap Forward campaign came to a close, as did the Four Pests Campaign. The legacy of this event was failure, but it also highlighted an issue that continues to be relevant.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

A Difficult Balance

Although the campaign had led to starvation and great loss, its complexity lies in its unfortunate benefits. The extermination of rats, flies, and mosquitoes led to not only lower disease transmissions but also better hygiene practices and cleanliness. This provided an example of the careful stability between pest control and maintaining the ecosystem.

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

Ambrica Productions, China: A Century of Revolution (1989)

They Tried Again

By 1998, China began a new rendition of the Four Pests Campaign which ended less successfully—but less disastrously as well. The targets were similar, but the government added cockroaches to the list among mosquitoes, rats, and flies. The problem was that the public had already been exterminating these pests on their own, so the campaign was redundant.

Connor Long, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Connor Long, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons