What really happened at Thermopylae?

The Battle of Thermopylae is a moment that came to define the struggles of the Greek city-states in their wars against the vast Persian Empire. Even though it wasn’t a victory, it was used to hold up the heroism, endurance, and sacrifice of the 300 Spartans who fell holding off hundreds of thousands of Persians.

But how much of this story has been fictionalized by the legend? Find out more with these epic facts about the battle that has captured our imaginations for more than 2,000 years.

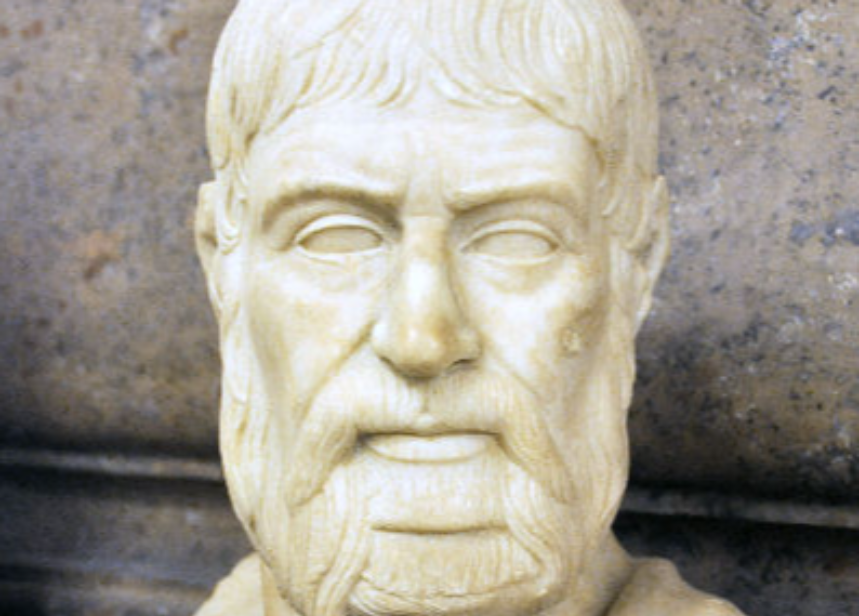

1. Such a Storyteller

The primary source for the Battle of Thermopylae comes from the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, known as the Father of History. To be fair, he was also called the Father of Lies for his tendency to also report on stories that were largely fictional, as well as for his exaggerations. Modern historians have had to take Herodotus’ comments with a grain of salt in search of the truth as opposed to his idea of a better story.

2. Just For the Record

Other ancient sources which commented on the Battle of Thermopylae include an account from the Sicilian historian Diodorus Siculus, whose own account was derived from a previous document on Thermopylae from the Greek historian Ephorus. The account is mostly consistent with the claims made by Herodotus. Aside from that, the battle is mentioned by such historians as Plutarch and Ctesias of Cnidus (yes that was his name).

3. Oh What’s in a Name?

The name "Thermopylae" translates to "Hot Gates" in the original Greek. This name was given to the narrow pass because of the warm sulphur springs which originated there. According to the Greek myths, the mighty warrior Heracles (often Latinized as Hercules) was tricked into putting on clothes which had been soaked in the blood of the Hydra. He was unable to take the clothes off and they began boiling him alive. When he jumped into the waters to cool himself down, the poison actually heated up the water and made it unhealthy , creating the sulphurous springs that gave the pass its name.

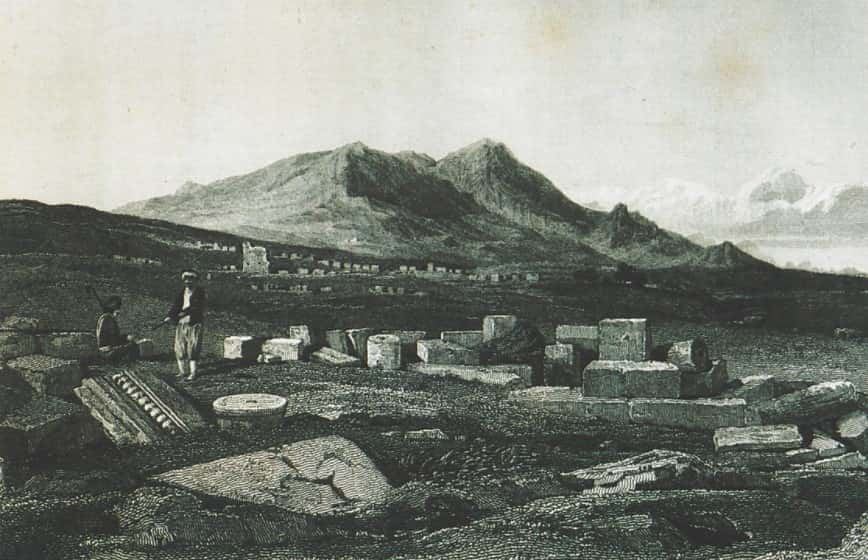

4. So Why Here?

Thermopylae was the ideal battleground for a defense against the Persians to protect the Greek regions such as Peloponnesus, Boeotia, Atticus, and Phocis. Back in antiquity, the pass was very narrow, ideal for a small number of army men to hold off a huge number of army men.

5. Who Started It?!

In around 480 BC, the Persian King of Kings Xerxes launched a massive land and sea invasion of Greece to avenge his father’s own failed invasion, which itself had only been launched when he had tried to subdue the Ionian Greeks in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). The Ionians had gotten support from other Greek city-states such as Athens and repelled the Persians, irking the Empire and leading to the Greco-Persian Wars which lasted half a century.

6. Accurate, but Also Inaccurate

In 300, one of the iconic scenes of the film was the scene where Persian messengers demands a gift of “earth and water". In response, Leonidas and his men cast the messengers into a well. According to Herodotus, this did actually happen, but not with Leonidas. This scene occurred prior to the invasion of Greece by Xerxes’ father, Darius I—long before Leonidas was king of Sparta.

7. Exaggerating, Much?

According to Herodotus, the Persian forces numbered no fewer than 2.5 million men and were also “accompanied by an equivalent number of support personnel". Not surprisingly, modern historians strongly dispute the idea of five million people somehow being fed and watered (not including the horses and other animals they must have brought). Ctesias reported a humbler estimate of 800,000 people making up the total invasion force, but even this is considered an exaggeration. Modern estimations have since put the Persian forces at 100,000 or perhaps even less than that.

8. Can Someone Take a Census?

There is a lot of dispute over the number of Greek army men who defended the pass at Thermopylae. Herodotus claimed it was between 5,200 and 6,100 (he doesn’t specify exactly how many army men made up “all they had” when it came to the men from Opuntian Locris). According to Diodorus Siculus, around 7,400 Greeks fought against the Persians. Either way, those 300 Spartans suddenly don’t seem quite so special, do they?

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

9. Where Does it End?

Among the many units in the Persian army, the elite army men were the ones whom the Greeks called the Persian Immortals (their original title in the Persian language has been lost to history). This unit, described by Herodotus as heavy infantry, were supposedly known as the Immortals because for every one of their members that was liquidated, lost, or incapacitated, a replacement was immediately brought in. This way, the Immortals never numbered more or less than 10,000 warriors.

10. Our King for Our Kingdom!

When word got out about the advancing Persian army, the Spartans sent an envoy to the Oracle at Delphi to find out whether they should march out to fight. The Oracle is said to have answered that the Spartans must “Mourn for the loss of a king” or else their “glorious town shall be sacked".

11. Senior Citizen

Contrary to what 300 might have told you, King Leonidas wasn’t a man in his prime with a Scottish accent. According to historical sources, Leonidas was said to have been an aging man at the Battle of Thermopylae, in his late 50s and maybe even as old as 60! To be honest, the fact that he was so old and still fighting Persians to the end makes his story even more impressive than if he was a young man—but maybe a little harder to cast.

12. Prepared to Go

Of the 300 Spartans that accompanied Leonidas to Thermopylae, the Spartan king made sure that he only brought men with living sons who could continue their family lines.

13. Sounds Like a Heck of a Week

The Battle of Thermopylae was reported to have lasted three days, though the Persians delayed for four days, reportedly because Xerxes couldn’t believe that such a small number of Greeks actually planned to fight his army.

14. Persia’s Pyrrhic Victory

While the Battle of Thermopylae was happening, the Battle of Artemisium was being fought on the sea. The combined Greek fleets met the much larger Persian fleet even as a storm was raging across part of the battlefield (is it still a field if it’s at sea?). Both sides suffered heavy losses, but it was harder on the Greeks, who lost between a third and half of their ships.

15. Marital Discussions

According to Plutarch, Leonidas was asked by his wife, Gorgo, what she should do if Leonidas did not return from the battle. He is said to have replied “Marry a good man and have good children".

16. How Are We Losing?!

On the first day of fighting, the Persians initially sent arrows at the Greeks, and when that failed to defeat them, a wave of Medes and Cissians struck the front lines, only for the Persian Immortals themselves to be sent forward when all else failed. So many men were said to have perished on the first day that Xerxes, who was observing the battle from a throne that they’d set up for him, jumped out of his seat three times in astonishment.

17. Psych!

As written down by the historians, the Greeks actually had more men than necessary to guard the pass effectively. This proved advantageous, as they could rotate men in and out of the pass to prevent fatigue from leading to more deaths than necessary. Also, in order to keep luring the Persians to further slaughter, the Greek army men would allegedly pretend to retreat. When the Persians charged forward, the Greeks would turn around and reform the line.

18. Day Two

On the second day, Xerxes renewed the assaults, believing that the Greeks must have become too exhausted to keep up their defense. He was proved wrong by the the time the sun set, much to his fury and confusion. It’s debatable what would have happened after that if a certain Greek hadn’t decided to visit Xerxes that night to tell him about a secret pathway around the pass.

19. Casualty Reports

According to Herodotus, 4,000 Greeks and 20,000 Persians perished during the Battle of Thermopylae. However, as with any of his claims, we have to take this with a grain of salt.

20. “Oh Dear, Drusus Didn’t Make it, Lads…”

During the Battle of Thermopylae, the Spartans had developed a primitive dog tag method to determine which of their number had been liquidated after a day of fighting. Each Spartan warrior would take a twig, give it a unique mark on both ends, and take half the twig with them into the fight. If they survived by the end of the day, they would return to camp and reclaim the other half of their twigs.

21. This is Our Home Court

The Greeks took advantage of the narrow pass to bottle the Persians into a confined place, where their different arms , armor, and fighting style proved deadly against the lightly armed Persians with their wickerwork shields. The Greeks were armored with bronze (not just abs, as the movie would make you believe) and strong wooden shields, which overlapped each other to make their line all the more difficult to break.

22. Laying the Foundations

Long before 300, Hollywood released a film in 1962 called The 300 Spartans. It was widely seen as being an allegory for the Cold Conflict , with the freedom-loving Greeks being a heroic stand-in for the West while they fought against the slave empire of the East (ironically, the film was a hit in the Soviet Union). On another note, artist Frank Miller saw the film as a child and was inspired to try his own hand at it many years later.

The 300 Spartans, 20th Century Fox

The 300 Spartans, 20th Century Fox

23. Setting a Trend

The term "Battle of Thermopylae" is generally accepted to refer to the fight which involved King Leonidas and the other Greek allies facing off against Xerxes and the Persians. However, it was only of at least eight different battles or skirmishes fought in that general area. Figures as prominent in history as Philip II of Macedon and Antiochus III the Great fought there, while the latest battle took place during World W. Two.

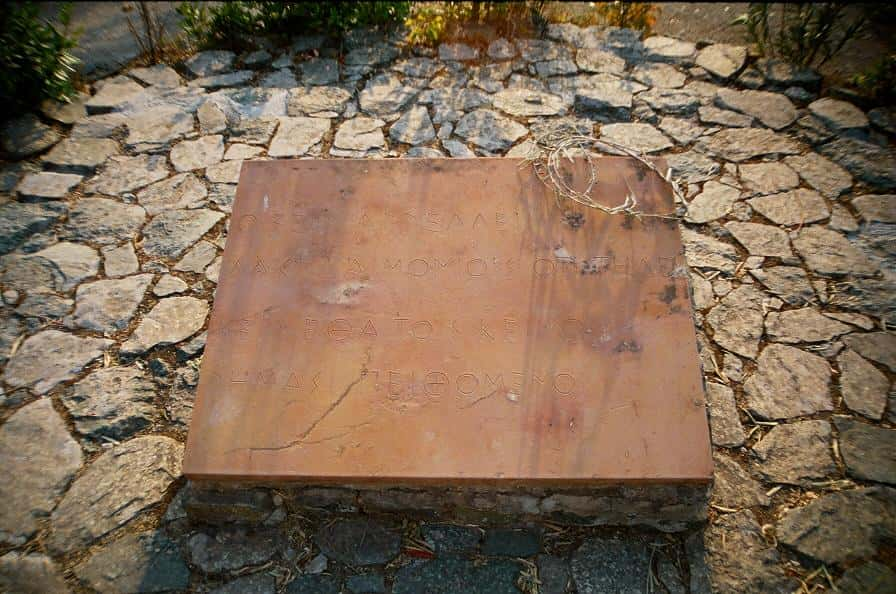

24. Beautiful Words

In the wake of the battle, a dedicatory stone was established where the Spartans were buried. An epitaph was carved into the stone, with the words supposedly coming from the poet Simonides. According to Herodotus, the words translated to “Oh stranger, tell the Lacedaemonians [Spartans] that we lie here, obedient to their words".

25. In Vain?

Despite the noble sacrifice of those Greek army men who had made a final stand to help their comrades get a head start on their retreat, it didn’t do much to save the city of Athens. Xerxes triumphantly marched his army across the Greek countryside and captured the city of Athens. However, the Athenians had prepared for this outcome and had deserted the city. Still, Xerxes took the time to raid and loot the great Greek city.

26. This Is a Bad Dream…

Speaking of that Greek traitor, he wasn’t exactly a deformed hunchback who’d been rejected by the Spartans for being unable to fight (nice try, Zack and Frank). In reality, Ephialtes of Trachis had a much simpler motivation to help the Persians get around Thermopylae; he wanted a reward. In "honor" of his betrayal, Ephialtes’ name now means "nightmare" in the Greek language. It is also an allegory for "traitor".

27. Not Sure Which One Sounds Better

The main Greek camp got word of the Persians encircling them. From here, Herodotus isn’t sure how exactly things went down among the Greeks; according to him, either Leonidas ordered the majority of his allies to retreat while they had the chance, or the Greek allies made their own decision to leave. Regardless, Leonidas was determined to fulfill the prophecy of the Oracle and sacrifice his life as a Spartan king to save his people from Persian rule.

28. So… 299 Spartans Then?

Not all the Spartans stayed at Thermopylae to perish. Two of the warriors, Aristodemus and Eurytus, were struck with “a disease of the eye". Leonidas considered both men unfit to fight, so he sent them home. According to Herodotus, this would have been acceptable to the Spartan populace if they’d both gone home. However, Eurytus turned back and rejoined the Spartans, even though he was pretty much blind, and perished at the pass. Aristodemus, meanwhile, went home to Sparta, where he was given the moniker "the Coward". He eventually fought at the Battle of Plataea, fighting with a wild ruthlessness—he was determined to redeem himself (though it cost him his life to do it).

29. Slave System

One popular belief that people have embraced about the Greeks at Thermopylae is the fact that the Greeks were fighting for their freedom against a Persian despot who enslaved various people to fight for him. However, the militaristic Spartans were famously masters of an entire enslaved class of people known as "helots," who performed all the menial tasks of keeping the Spartan economy and systems functioning while giving the Spartan citizens the ability to be career army men. Meanwhile, the Persian Empire was known for its relatively fair treatment of conquered territories.

300: Rise of an Empire (2014), Warner Bros.

300: Rise of an Empire (2014), Warner Bros.

30. Three Per Spartan

Speaking of those helots (AKA slaves), around 900 of them were said to have accompanied the 300 Spartans to the Battle of Thermopylae, staying behind with them in the fight to the end . Their presence, admittedly, is debatable, as is the question of how exactly these helots were convinced (or forced) to join their masters in demise, but we’ll leave that for the scholars to answer in the comments section.

31. Too Good to Make Up

Incredibly, 300 got a few quotes completely accurate about the Battle of Thermopylae, if the historical records can be trusted. King Leonidas allegedly did answer “Come and get them!” in response to Persian demands for the Greeks’ arms. Likewise, both Plutarch and Herodotus claim an exchange happened where a joke was made about fighting in the shade while the Persian arrows blocked the sun itself. However, the historians disagree on who said the punchline, with Herodotus crediting a Spartan named Dienekes and Plutarch claiming it was Leonidas.

32. Make a Reservation for 300 at the Barber Shop

Reportedly, while the Persians were waiting for the Greek forces to disperse and let them through the pass, they made a rather ironic mistake. They sent spies to observe the Greeks in their camp, particularly the Spartans. One spy observed the Spartans perfuming and oiling their hair. This reportedly gave the Persians the sense that the Spartans weren’t to be taken seriously, but they failed to understand that when a Spartan warrior was working on their hair, they were preparing for a fight to the end. This just proves that 300 failed big time in an epic scene where we watched the Spartans all get brand new hairstyles for the big fight!

33. Call It a Fitting Reward?

So what happened to Ephialtes of Trachis, you might be wondering. The Persians’ promises of reward were dashed when their fleet was destroyed at the Battle of Salamis. With a bounty on his head, Ephialtes went on the run for Thessaly, in northern Greece. According to Herodotus, Ephialtes met a violent end when he was ended by a man named Athenades for reasons completely unrelated to Thermopylae. Despite that fact, the Spartans still rewarded him.

34. Aftermath

It took the Greeks 40 years to bring Leonidas’ bones back to Sparta (and to be fair, we’ll never know if they really were his bones). Soon after the Persians were finally driven out of Greece, however, the pass at Thermopylae was decorated with a stone lion in honor of the Spartan king.

35. On the One Hand…

The Second Persian Invasion of Greece was only halted by the Greek naval victory at Salamis and the land victory at Plataea. The latter involved an army of Greeks led by the Spartan general and regent Pausanias. Both those victories, followed with a final triumph at Mycale, sadly makes the defeat at Thermopylae look a bit less significant than Frank Miller would probably want you to believe.

Jona Lendering, Wikimedia Commons

Jona Lendering, Wikimedia Commons

36. On the Other Hand…

Despite the lack of resolution to the conflict between the Greeks and the Persians, historians do still argue for the importance of Thermopylae as a delaying action which allowed the other Greeks time to prepare for the subsequent victories. Others try to put the focus on the nobility of the Greeks’ final stand at Thermopylae in the face of defeat, seeking to defy their enemies to the bitter end.

37. We Stand Alone! Wait…

Contrary to the popular belief, the 300 Spartans were not even alone for their final stand. Over 700 army men from Thespiae chose to stay behind with the Spartans, as did 400 men from Thebes.

38. Guard It!

Contrary to what 300 portrays (that sure has come up a lot in this article) King Leonidas and the other Greeks were fully aware of the secret track which led around the pass of Thermopylae. Over 1,000 Phocians were stationed to guard the pass in case anyone happened to find it.

39. You Had One Job!!!!

The Persians were told about the secret track by a Greek traitor. When the Phocians guarding the pass got wind of the massive Persian forces coming their way, they pulled back to a hill to make their final stand. However, the Persians didn’t plan on delaying anymore and left the Phocians where they were as they continued on to the encircle the Greeks. We can only imagine how sheepish and embarrassed the Phocians must have felt as they watched the Persians ignore them.

40. Make that 298 Spartans

A Spartan named Pantites was sent on a mission to Thessaly in order to find reinforcements. Unfortunately for Pantites, he returned too late to join in the battle. Like Aristodemus, Pantites was regarded as a disgrace by the other Spartans. Sadly, Pantites was driven to such despair by his compatriots that he hanged himself to put an end his humiliation.

41. A Tendency for the Dramatic

The Thespian example is especially noteworthy. Unlike with Sparta, the 700 hoplites from Thespiae represented their entire fighting force. While it’s true that they stood to lose a great deal if the Persians got through Thermopylae, it’s worth pointing out that by this time, the city of Thespiae had been successfully evacuated. The conclusion is that the Thespian army chose Thermopylae to make their heroic final stand en masse, something which the Thespians would go on to do two other times later in their history.

42. A Fallen King

After the battle was finally won by the Persians and the remaining rear guard of Greeks had been ended(many of them by the Persian archers, as later excavation would prove), the leader of the Greek forces was given a particularly humiliating punishment by the Persians. Although Leonidas’ body had been fought over by the surviving Greeks to protect it from desecration (as opposed to him being the last surviving man to be ended), the body of the Spartan king was beheaded and crucified. This went against the custom of the Persians, who normally treated their fallen enemies with honor, but Xerxes was feeling particularly ticked off after a week’s delay and a particularly humiliating battle in which thousands of his men had ended.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17