Field Marshal Bernard Law "Monty" Montgomery was instrumental in defeating the Axis forces during WWII. His strategic brilliance, however, was second only to his massive ego and total lack of tact. Even so, more people need to know about Bernard "Monty" Montgomery, the man who Winston Churchill himself described as, "In defeat, unbeatable; in victory, unbearable".

1. His Parents Were Strict

Bernard Law "Monty" Montgomery was born in 1887 in London, England to a particularly strict and zealous family. His father, Henry Montgomery, was a minister with the Church of Ireland while his mother, Maud, was the daughter of a reverend. However, Monty never had any plans of following in his parents' footsteps or walking the straight-and-narrow.

2. He Didn’t Have Much

Despite his family’s illustrious history, Monty didn’t exactly grow up in luxury. In fact, when Monty was just a few months old, his father inherited the family estate New Park—and all of its crippling debts. According to the elder Montgomery, after selling off most of the land, "there was barely enough to keep up New Park and pay for the blasted summer holiday".

Soon, the financial stresses took their toll.

3. He Went "Down Under"

When Monty was two years old, a momentous change came to his family: His father became the Bishop of Tasmania and the family packed up and moved to Australia. Unfortunately, this wasn't a good move for the brood, and you might say that his childhood went "down under". Under the stresses of his work, his father left the family for months at a time, leaving Monty and his eight siblings at their mother’s mercy.

And she didn’t exactly have a lot of mercy.

4. His Mother Beat Him

Monty's mother, overwhelmed as she was with raising a family in a strange new world, often ignored him and his siblings. Yet when she did pay attention to him, she would give him devastating beatings, usually for what she viewed to be insubordination. To be fair, Monty was quite the rebel: He liked to order about his brothers, take sweets from his mother, and sold the bike she had gifted him for a stamp collection he liked more.

But as any armchair psychologist will tell you, all of that was likely all just a cry for help and attention. Those cries would only grow louder—and more disturbing.

5. He Was A Bully

Perhaps because of his mother’s parenting style and their incessant head-butting, Monty developed a penchant for fighting early on. Yet since he could hardly take it out on the matriarch of the family, he turned to his smaller, less powerful schoolmates. He'd play cruel, authoritarian games with them, at one point even forcing a group of boys to walk up a ladder and across a roof with their hands tied together.

Worst of all, Monty knew he was the "bad boy of the family," as one of his siblings put it. "I was a dreadful little boy," he recalled decades later. "I don't suppose anybody would put up with my sort of [behavior] these days". They barely put up with it then.

6. He Was Rowdy

Thankfully, Monty’s nightmare in Australia came to an end in 1901 when his family returned to London. But the damage was already done; Monty had grown into a fully unpleasant young man. In fact, shortly thereafter, he attended the Royal Military College, Sandhurst, but even the strict officers of the British Army had a tough time straightening him out.

His superiors nearly expelled him for his "rowdiness and violence," which had to be very rowdy and very violent for the Army to nearly expel him.

7. He Was A Lieutenant

Monty miraculously managed to follow orders long enough to graduate from RMC, Sandhurst at the age of 21. And he was eager to get his hands dirty—or bloody. Shortly after graduating, Monty saw a little action in India, and, perhaps because of his brutality in battle, managed to attain the rank of lieutenant. But it wasn’t until the outbreak of WWI that he would really distinguish himself.

8. He Was Shot In The Lung

At the outbreak of WWI, Monty went to France with his battalion. And he very nearly never made it back to Britain—at least not alive. In the heat of the First Battle of Ypres, Monty fell into a sniper’s crosshairs—and they didn't miss. He took one shot to his right lung and another one to the knee. By the time he crawled to safety, there was more of his blood on the battlefield than there was in his body.

9. He Had One Foot In The Grave

No one expected Montgomery to survive his injuries. In fact, the doctors attending to him were so certain that he would only return to Britain in a coffin that the British Army prepared his grave. But if Monty could survive his mother, then he could certainly survive a little scratch to the lung and knee. Plus, he was now a hero.

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

10. He Was Conspicuously Gallant

For his gallant leadership (and miraculous recovery), Montgomery received the Distinguished Service Order medal. Even the London Gazette hailed his early heroics. The paper wrote that he had received the medal for "Conspicuous gallant leading on 13th October, when he [Montgomery] turned the enemy out of their trenches with the bayonet". His real achievements, however, still lay ahead of him.

11. He Got Back In The Fight

Not only did Monty live to tell the tale of his run-in with an unknown sniper, but he got right back into the fight. After recovering in 1915, Monty returned to the frontlines of the conflict to finish the job. And he continued to distinguish himself, rising up the ranks to the position of staff officer by the time the Allies declared victory.

But it was a victory paid for in blood—too much blood, Montgomery thought.

12. He Was Appalled By Casualties

Considering his mother’s constant beatings, Monty was no stranger to the horrors of savagery and brutality. But the sheer terror of what he had witnessed during WWI changed him forever. "The frightful casualties appalled me," Monty wrote of his experience decades later. He felt as though generals on both sides of the conflict had a complete disregard for human life. So he decided that he would be different.

13. He Dedicated Himself To The Army

After his experience in WWI, Montgomery found his purpose in life. He saw incompetence in most of the officers around him, and he determined to devote his life to the arts of battle: "I decided to dedicate myself to my profession, to master its details and to put all else aside". And by all else, he really meant all else.

14. He Hit An Ace

In order to attain any real rank within the British Army, Monty knew that he needed an education—and a better attitude. Lacking the right family connections and a basic ability to follow his superiors’ orders, Monty failed to get into Staff College. But, a chance invitation to play tennis brought him face-to-face with the Commander-in-chief.

He impressed the Commander enough to secure himself a position at Staff College.

15. He Didn’t Have The Luck Of The Irish

Once again, Monty swallowed his ego long enough to graduate from Staff College in 1921 as brigade major. However, he quickly found himself in an unwinnable situation. Stationed with the 17th Infantry Brigade in Ireland, Monty was tasked with "counter-insurgency operations" against Irish nationalists. Faced with his no-win situation, Monty abandoned any notion of clemency or pacifism.

In Ireland, he meant business. Bloody business.

16. He Tried To Appear Strong

Ireland was Monty’s first real leadership position. And he learned pretty quickly that he wasn’t as formidable as he thought he was. In May of 1922, he led a substantial force into the town of Macroom in search of some British officers who had gone missing. Montgomery had hoped that his show force would compel the IRA commander, Charlie Browne, to spill the beans.

Instead, however, he only incurred Browne’s wrath.

17. He Had 10 Minutes To Live

Browne lured Monty into a trap by calmly agreeing to a parley outside of the castle gates. Carefully, Monty explained to Browne what would happen if he didn’t turn over the missing officers. After listening attentively, however, Browne simply turned on his heel and informed Monty that he had 10 minutes to leave town. Monty was about to find out that he wasn’t the most ruthless man in Ireland.

18. He Was Out-Flanked

Once Browne had retreated behind the castle walls, another IRA officer, Pat O’Sullivan, whistled, capturing Monty’s attention. When Monty looked up, he realized that dozens upon dozens of IRA volunteers had taken up firing positions, completely surrounding him and his men. With his tail between his legs, Montgomery had no choice but to retreat and beg for mercy from his commanding officers back in Britain.

19. He Won By Losing

Monty’s decision to retreat and save his men (and his badly bruised ego) drew criticism from politicians back in London. However, Monty’s superior officers defended his decision to retreat. And, as it turns out, it was the right decision. By the time Monty had arrived in Macroom, the IRA had already executed the missing British officers.

But it was only payback for the unspeakable things that Monty had done to them.

20. He Burned Peoples’ Houses Down

In Ireland, Montgomery unleashed a scorched earth campaign of utter barbarism. "Personally," he said, "my whole attention was given to defeating the rebels but it never bothered me a bit how many houses were burnt". As far as he was concerned, even civilians were fair game, referring to them in derogatory terms. Fortunately for the Irish, politicians back in Britain managed to find a diplomatic solution to the conflict before Monty burned the whole place down.

21. He Didn’t Have A Life

When he wasn’t burning peoples’ houses to the ground, Montgomery tried to have some semblance of a personal life. But his fanatical dedication to his career in the British Army and the "study of arms" made that difficult. It wasn’t until he was in his late-30s, in 1925, that Monty managed to cobble together something resembling a romantic side.

But love, as they say, is a battlefield. Quite literally, in Monty’s case.

22. He Was No Casanova

Monty’s first-ever romantic interest was a 17-year-old girl named Betty Anderson. But, if you ever thought that your first date was awkward, then it’s only because you haven’t dated Bernard Law Montgomery. Apparently, Monty’s idea of a romantic walk on the beach included "drawing diagrams in the sand" of hypothetical troop and armored vehicle deployments. Swoon.

23. He Found His Equal

Needless to say, Monty’s "flirtatious" drawings of tanks and heavy infantry didn’t exactly impress Anderson and she turned down his proposal. A few years later, however, Monty met Elizabeth (Betty) Carver. As the widowed sister of a British Army officer, she and her two sons fit seamlessly into Monty’s life. For a while, it seemed like he had managed to make a family for himself.

Sadly, all good things come to an end.

24. He Did A Very Brave Thing

By all accounts, Monty’s marriage to Carver was a happy and peaceful reprieve from the savagery of his day job. Even his stepsons seemed to admire him, later saying that he had done "a very brave thing" in marrying their widowed mother. Additionally, a few short years after their marriage, Monty and Carver had a child of their own; a son named David.

Try as he might, however, Montgomery could not escape tragedy.

25. His Wife Fought For Her Life

Even on vacation, Monty had to be prepared for a fight. But, this time, his wife would be the one fighting—and she would be fighting for her life. While they were vacationing in Burnham-on-sea, Carver received a mysterious insect bite. Within no time at all, the bite became severely infected, requiring amputation of her leg. Sadly, for Monty, his wife wasn’t as strong a fighter as he was.

26. He Held His Dying Wife

While Monty would have seen all kinds of grievous injuries and diseases during his service, nothing could have prepared him for the tragedy that came next. His wife’s condition did not improve following the amputation. The infection had already spread and she developed either sepsis or septicemia. Tragically, all Monty could do was hold onto his wife as the life slipped out of her body.

Utterly devastated, Montgomery resolved to throw himself into his work right after the funeral. And thank goodness he did.

27. He Was Eager For A Fight

Following his wife’s passing, Monty threw away any vestiges of hope for a normal life and rededicated himself to the army. He was quickly promoted to the rank of major-general and sent to Mandatory Palestine, far away from the tragic memory of his dearly departed wife. While there, the grieving widower took out his frustrations on the Great Palestinian Revolt, crushing all resistance.

Less than a year later, however, he was back in England and pining for another fight. He would get more than he asked for.

28. He Annoyed His Superiors

Only a few months after his return to England, much to his excitement, WWII broke out on the European continent. Monty found himself once again in France as part of the 3rd Division. Even before the first shots rang out or mortars flew, however, Monty’s leadership style began irritating his superiors. He was, shall we say, a little unrefined.

29. He Was Obscene

Even though Monty had given up on his own carnal needs after his wife’s unexpected expiration, he understood that his men still had physical urges. And he had no problem reminding them to "play safe," as it were. But, apparently, in reminding his men to avoid venereal diseases, Monty had used such "obscene language" that even his battle-hardened superiors thought about giving him the boot.

30. He Was The Drill Master

Explicit descriptions of venereal diseases aside, Monty’s leadership in the early stages of WWII proved to be invaluable. While the other Divisions in France began digging in for defense, Monty drilled the 3rd Division into the finest fighting force west of the Rhine. He often insisted that they carry out their training exercises at night when the conditions were poor.

Despite some moaning and groaning from his men, his hard drilling saved lives.

31. He Saved Countless Lives

By the time the conflict started in earnest, Monty’s 3rd Division had already developed a reputation as "a very agile and flexible formation". And they would have to be. As France fell to the evil Axis forces, Monty’s 3rd Division was "always in the right place at the right time" to cover the British retreat at Dunkirk. There’s no telling how many lives his drills saved.

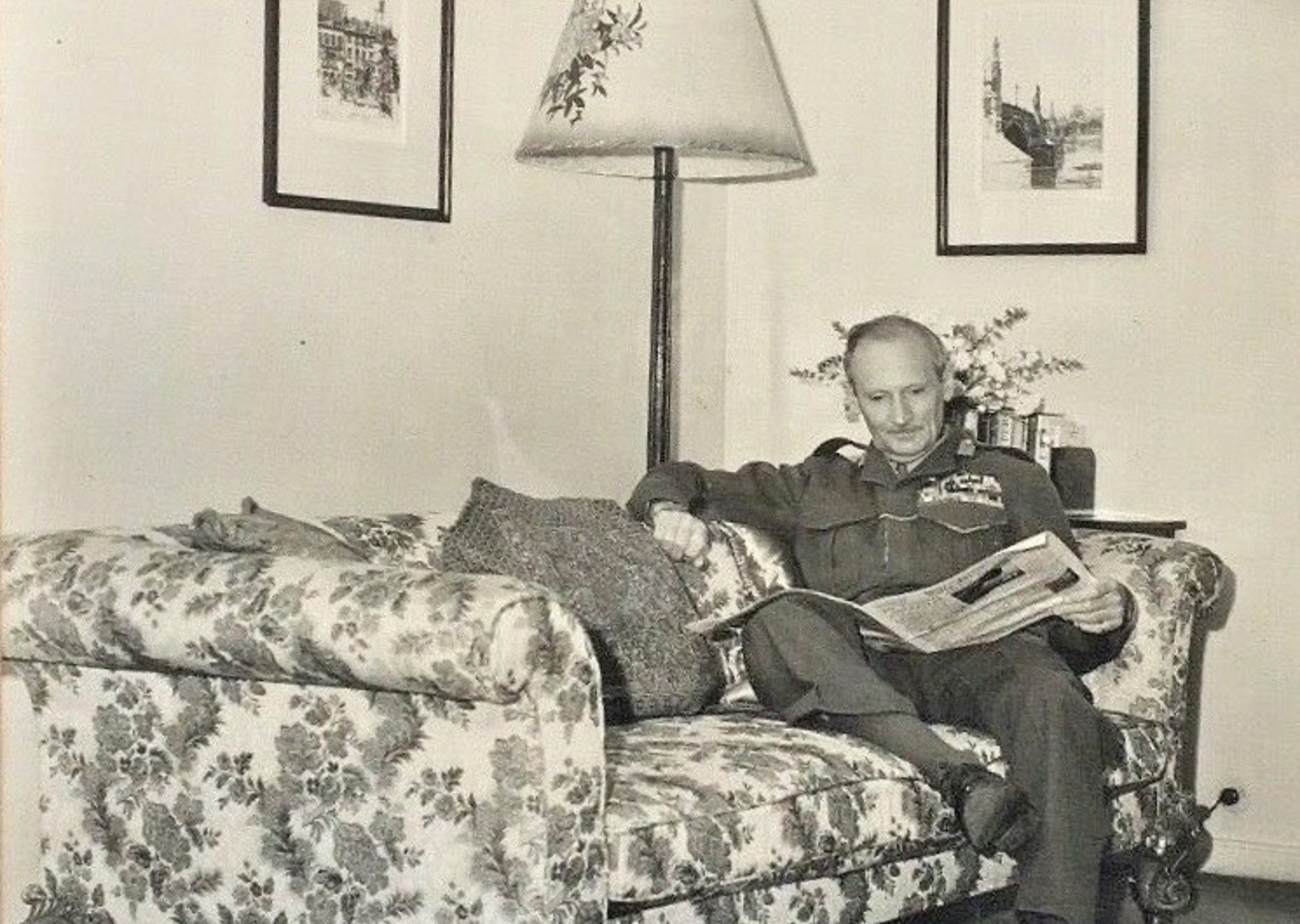

32. He Had A Bedtime

It was during that first deployment to France that some of Monty’s quirks made themselves apparent—and problematic. Perhaps his most notable quirk was his strict practice of going to bed at precisely 9:30 every night—artillery fire or no artillery fire. Before he retired for the evening, he gave his men just one order: not to disturb him. Unless, of course, there was an emergency.

33. His Plans Went Unused

Despite his abrasive and off-putting personality, British Army Command knew that Monty had a brilliant mind when it came to battle planning. They tolerated him long enough to listen to his plans to invade the Azores, Cape Verde, and even Ireland. Much to his chagrin, however, none of those planned invasions ever actually occurred. But the battle of his lifetime was just around the corner.

34. He Received A Big Promotion

By 1942, the tide was turning in favor of the Allies and Winston Churchill needed a new field commander in North Africa. Despite his reputation for being a little hard-headed (or because of it), Churchill chose Monty. But waiting for him in the Sahara was the dreaded German field marshal—the Desert Fox, Erwin Rommel. The desert sand was about to get wet with blood.

35. He Warned Rommel

After receiving his promotion, Monty is alleged to have said, "After having an easy [fight], things have now got much more difficult". One of his colleagues supposedly told him to lighten up. Monty responded by saying, "I'm not talking about me, I'm talking about Rommel!" For all of his bravado, however, victory against the Desert Fox would not come easy. In fact, it would nearly cost him everything.

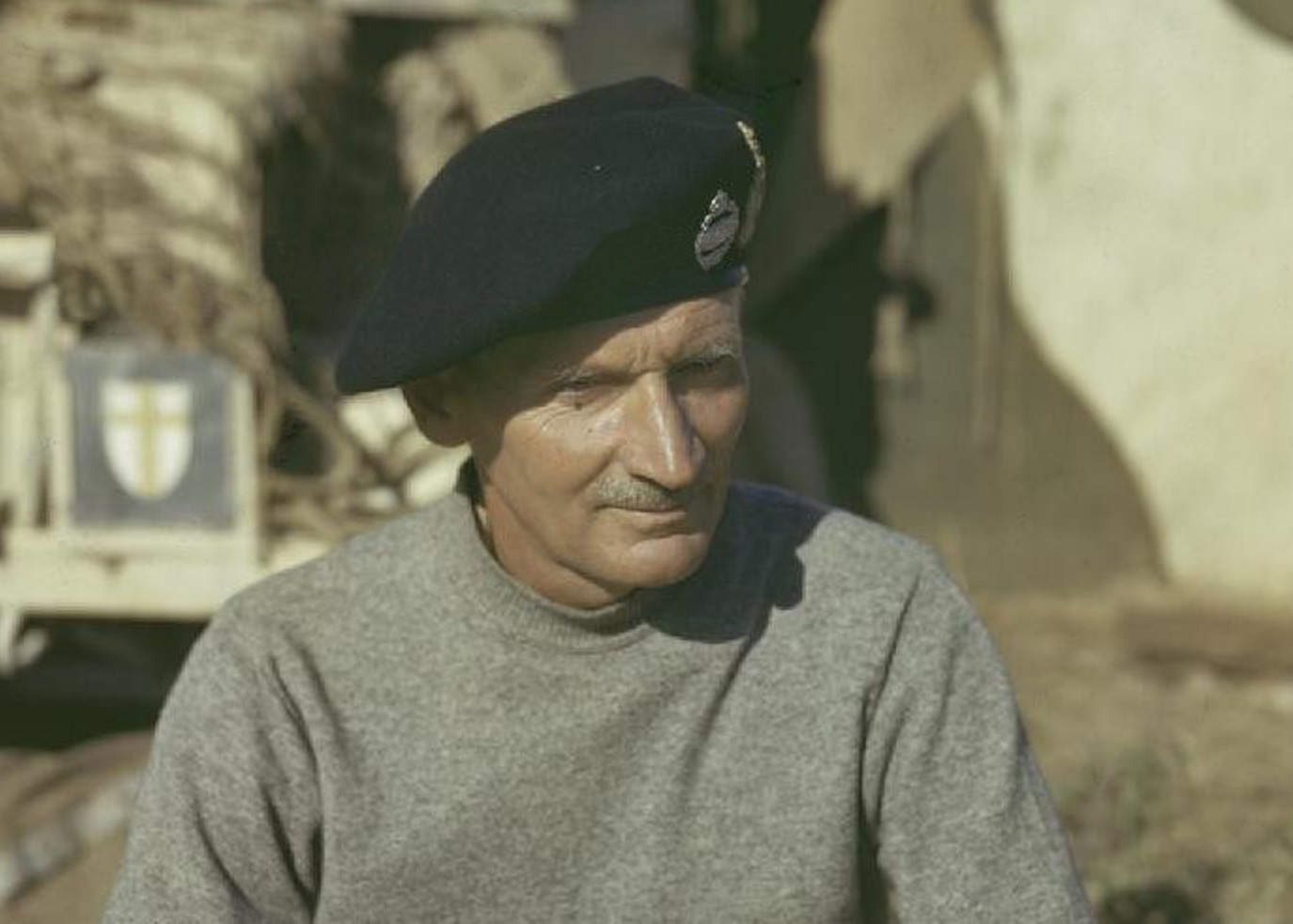

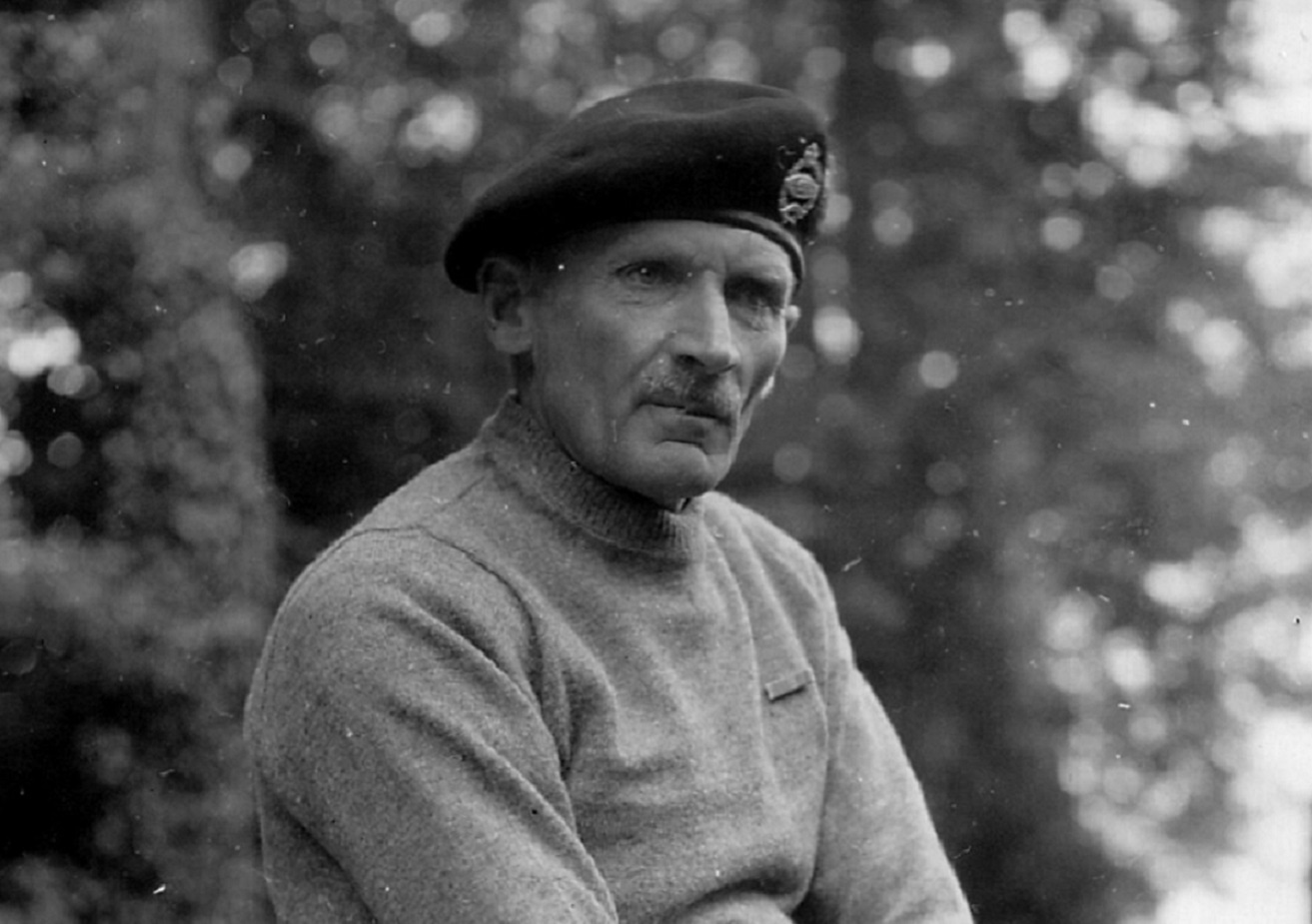

Wikimedia Commons, Cassowary Colorizations

Wikimedia Commons, Cassowary Colorizations

36. He Had No Exit Strategy

Monty was a lot of things, but he was not a quitter. At his very first meeting in the desert with his officers, Monty made it clear that they would either beat Rommel or go to their grave trying. "I have [canceled] the plan for withdrawal," he said. "If we are attacked, then there will be no retreat. If we cannot stay here alive, then we will stay here dead". And he wasn’t bluffing.

37. He Was Good For Morale

Within just one week of arriving in North Africa, Monty had restored morale amongst the men. "I want to impose on everyone that the bad times are over, they are finished!" he exclaimed. "Our mandate from the Prime Minister is to destroy the Axis forces in North Africa[...]It can be done, and it will be done!" And he’d see to it personally.

38. He Was Too Slow

Monty spent months fending off Rommel’s repeated offensives and preparing for a tide-turning battle. But, to his superiors, it looked like he had turned coward. Back in England, Churchill demanded action but Monty brushed him off and continued building up the strength of the Eighth Army. Even in the desert, slow and steady wins the race—or, in this case, the decisive battle of WWII.

39. He Turned The Tide Of Battle

In late October 1942, much to his superiors’ delight and relief, Monty launched his much-anticipated counter-offensive. The Second Battle of El Alamein lasted 12 days and resulted in 13,500 casualties. But Monty had his victory and, most, importantly, the opportunity to thumb his nose at those who had doubted him. He had just delivered the Allies one of their greatest land victories since WWII had begun. But it cost him dearly.

40. He Couldn’t Save His Stepson

If anyone understood that victory always came at a cost, it should have been Monty. Nevertheless, he was caught off guard shortly after his resounding success in the Second Battle of El Alamein. Monty’s stepson, Dick Carver, fell into enemy hands while out on a scouting mission. What little family Monty had left was then in the hands of the enemy.

41. He Got A Christmas Miracle

Monty only gave the impression that he was a cold and calculating man of action. In reality, he had a few soft spots—and the enemy had just captured one of them. In a frantic state, Monty exhausted his resources and contacts in a vain attempt to retrieve his stepson. For once, however, the fates were kind. Carver managed to escape on his own and found his way back to Monty in time for Christmas.

42. He Bickered With His Allies

As Montgomery racked up victory after victory against Rommel, his ego grew bigger and bigger. Too big, in fact, to fit inside the Allies’ camp. By the time he was promoted to full general, he found himself working alongside his US allies George Patton and Omar Bradley. And, from the sounds of it, the real fighting happened between those three who squabbled "like three schoolgirls".

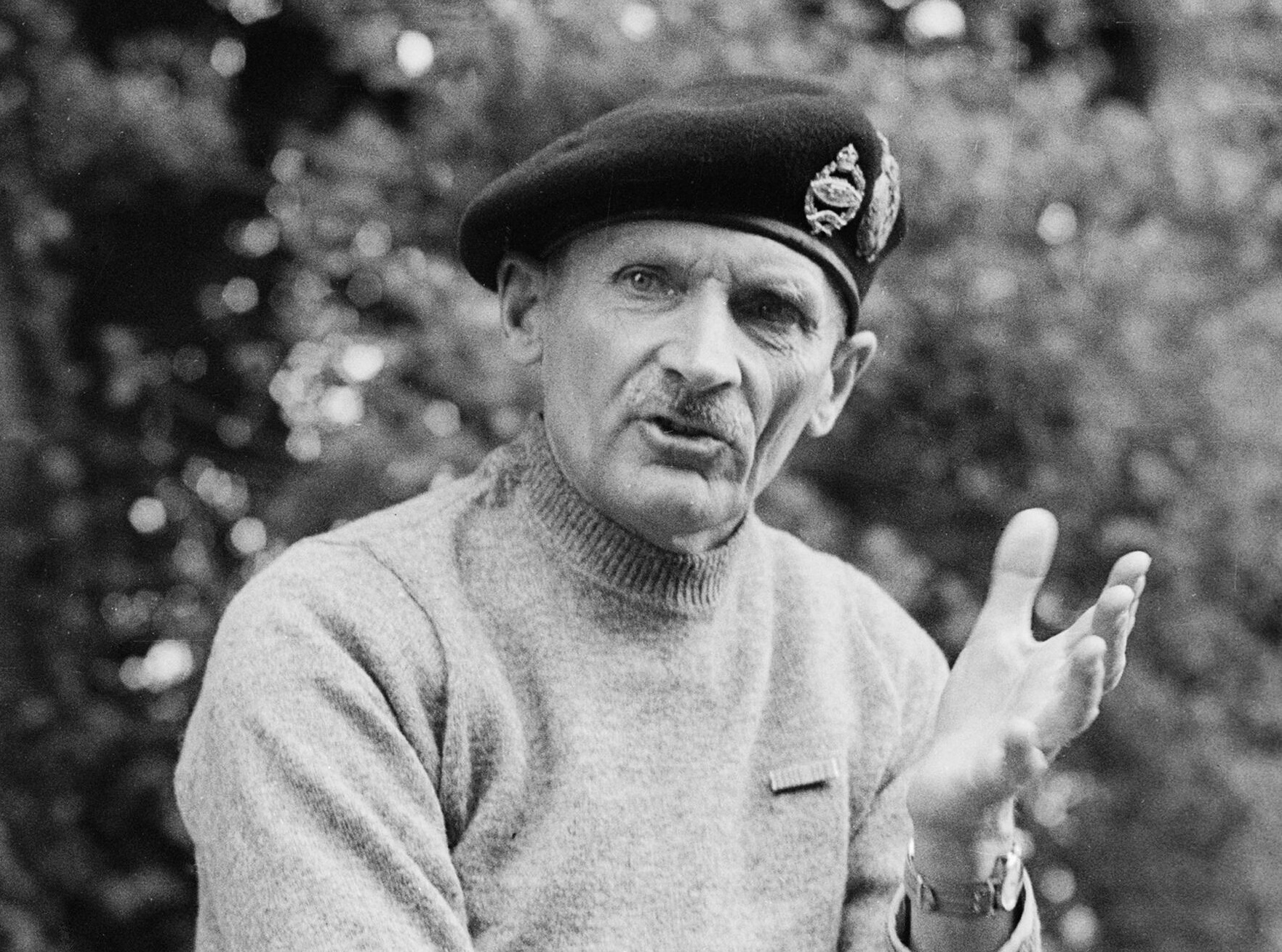

43. He Had The Führer On A Leash

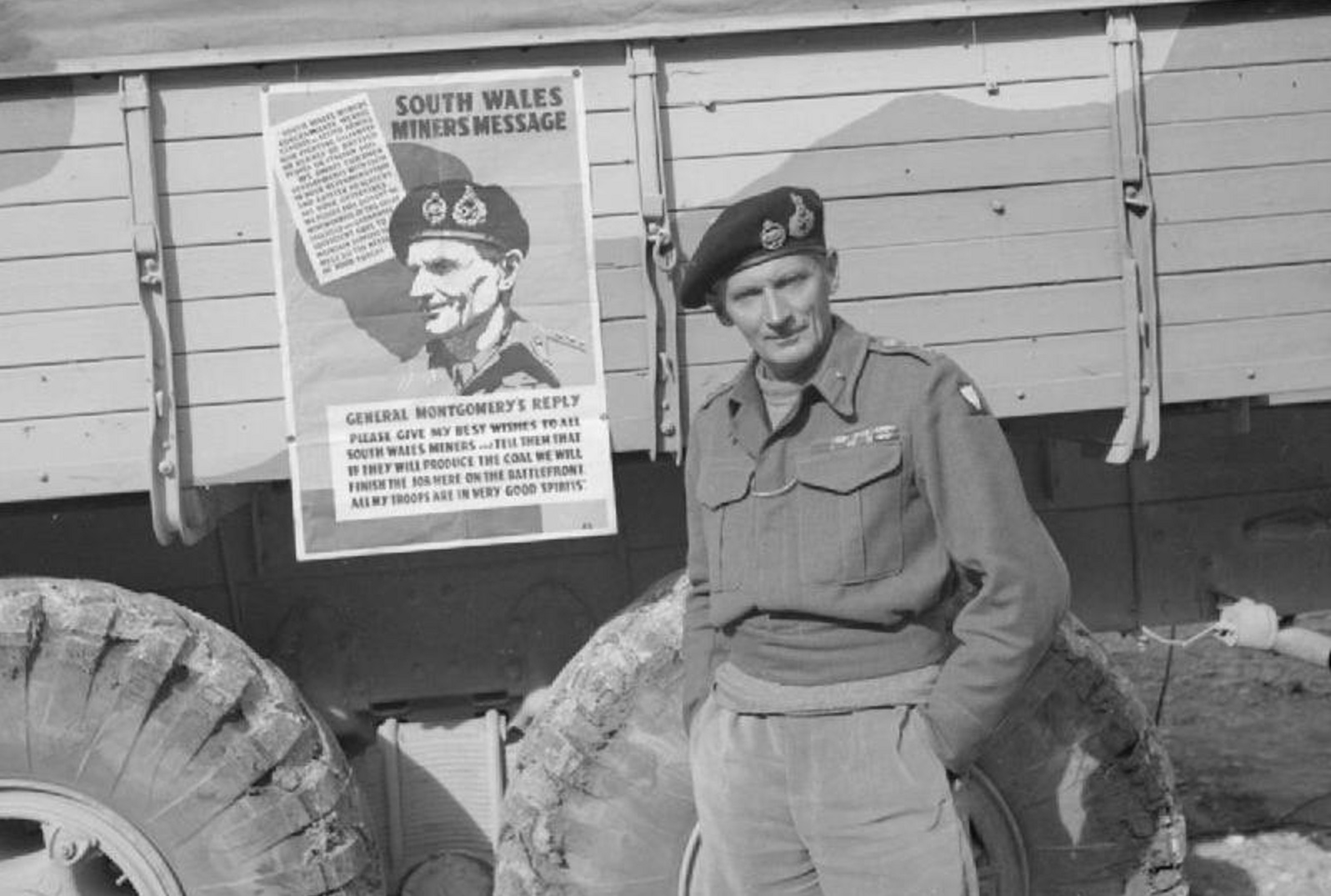

Even though he was a total nightmare to work with, Monty had a decent (if morbid) sense of humor that he applied to his two pet dogs. A photograph of Monty taken in 1944 shows him with his two canine friends. One, a fox terrier, named after the hated Führer of the Third Reich himself, and the other, a spaniel, named Rommel. Perhaps Monty got away with it because he effectively had both the führer and Rommel on a leash.

44. He Made A Reckless Gamble

Monty was known for being "arrogant", "unlikeable" and "boastful". He was also strangely literal. For example, he made a bet with US General Walter Bedell Smith that he could capture the town of Sfax by mid-April 1943. As a joke, Smith wagered that, if Montgomery succeeded in Sfax, he would personally give him a Flying Fortress. He should have chosen his words more wisely.

45. He Couldn’t Take A Joke

While Smith was obviously joking, Monty was not. Just as he had planned, Monty captured Sfax in early April and promptly reached out to Smith to "collect his winnings". When Smith realized that Monty wasn’t joking, he had to go hat-in-hand to Dwight D. Eisenhower who begrudgingly handed over a fully-staffed Boeing B-17 to Monty.

46. His Friends Couldn’t Stand Him

There was, perhaps, only one person who could put up with Monty’s abrasive personality. That was General Sir Alan Brooke, the head of the British Army. But at times, even he couldn’t stand Monty. He regularly complained about Montgomery in his diaries, writing, "I had to haul him over the coals for his usual lack of tact and egotistical outlook".

47. He Was In It For The Money

Like all narcissists (and young girls), Monty kept a detailed secret diary. When, in 1944, he told the American journalist John Gunther about his ongoing memoirs, Gunther informed him that he could likely get a pretty penny for it out of future historians. At the thought of pocketing some cash, Monty grinned and said, "Well, I guess I won't die in the poor house after all".

48. He Was Not A Momma’s Boy

In 1949, Monty’s crotchety old mother finally croaked. But the passage of time hadn’t dampened his resentment towards her for her brutal parenting style. The then 62-year-old Lord Montgomery chose not to attend his own mother’s funeral, claiming that he was "too busy". In the end, however, it was likely her aggression that had prepared him for a life of battle.

49. He Was Actually "Mad"

Following WWII, Montgomery held a number of high-ranking positions, but he never quite exerted as much influence as he wanted to—and he only had himself and his own bad attitude to blame. As one of his detractors put it, "I have come to the conclusion that his love of publicity is a disease[...]and that it sends him equally mad".

50. He Had Some Controversial Opinions

Towards the end of his life, Montgomery adopted controversial opinions that betrayed the fact that he had, maybe, outlived his usefulness. He was an outspoken supporter of apartheid in South Africa and an opponent of gay rights. He famously said, "this sort of thing [homosexuality] may be tolerated by the French, but we’re British—thank God".

51. He Was All About Discipline

Monty didn’t just demand discipline from his men. He expected it of himself as well. All throughout his life, he was a teetotaller (i.e., he didn’t drink anything intoxicating), a particularly dedicated vegetarian (he’d probably seen too much carnage in his life), and a practicing Christian. In other words, it’s not entirely clear that, in his 88 years, he enjoyed anything other than a good fight.