A Bloody Legacy

You may have heard of Bastille Day, or the Storming of the Bastille. But how much do you really know about the history of the Bastille? What is the Bastille? And why does it still inspire the French, even while evoking a history of violence and bloodshed?

Why Is Bastille Day Celebrated?

On July 14 every year, France celebrates Fête nationale française, meaning French National Day (officially called le 14 juillet). "Bastille Day" is the common English name for the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille. A key moment in the French Revolution, July 14 is a celebration of the unity of the French people.

So What Happened?

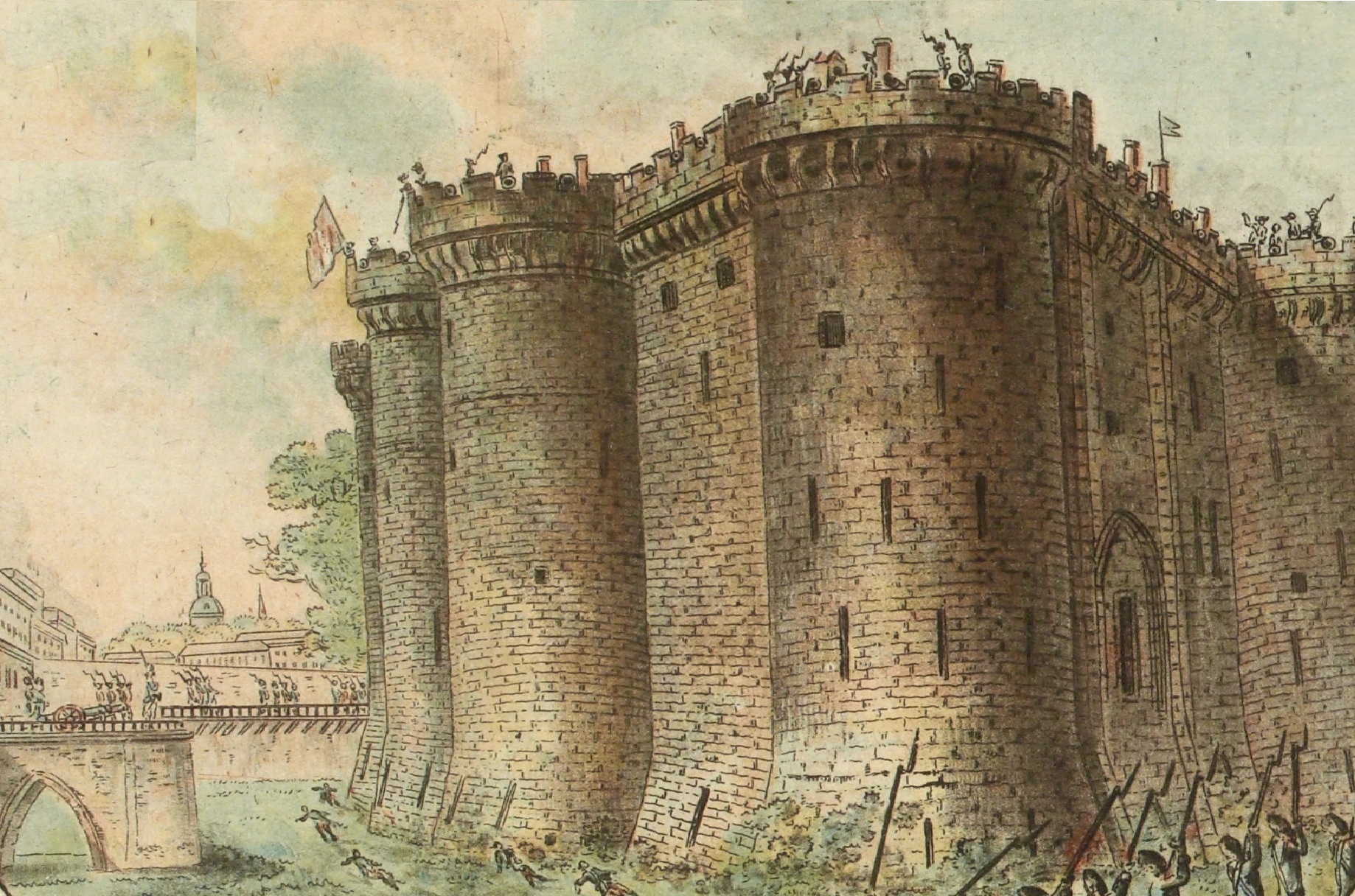

The Bastille was a military fortress and prison, and it had become a symbol of the power and the tyranny of the French monarchy and aristocracy. On July 14, 1789, French revolutionaries stormed the Bastille as one of the first moments of the French Revolution. One year later the French celebrated the anniversary as a national holiday.

Jean-Pierre Houël, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Pierre Houël, Wikimedia Commons

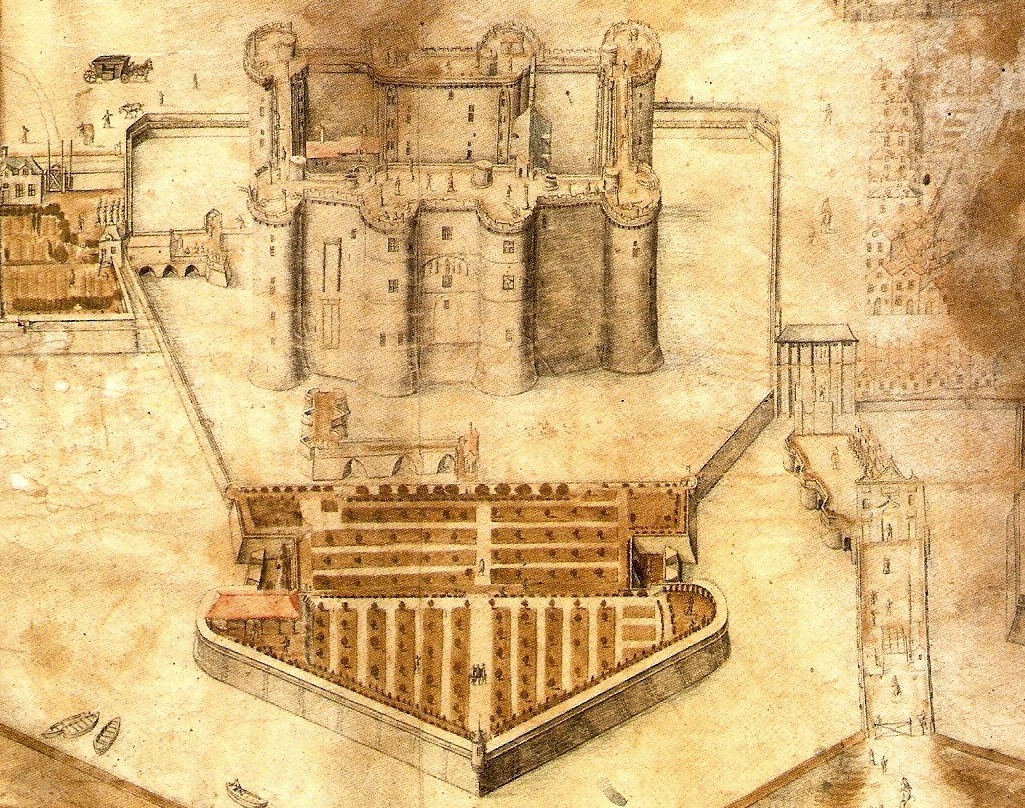

What Was The Bastille?

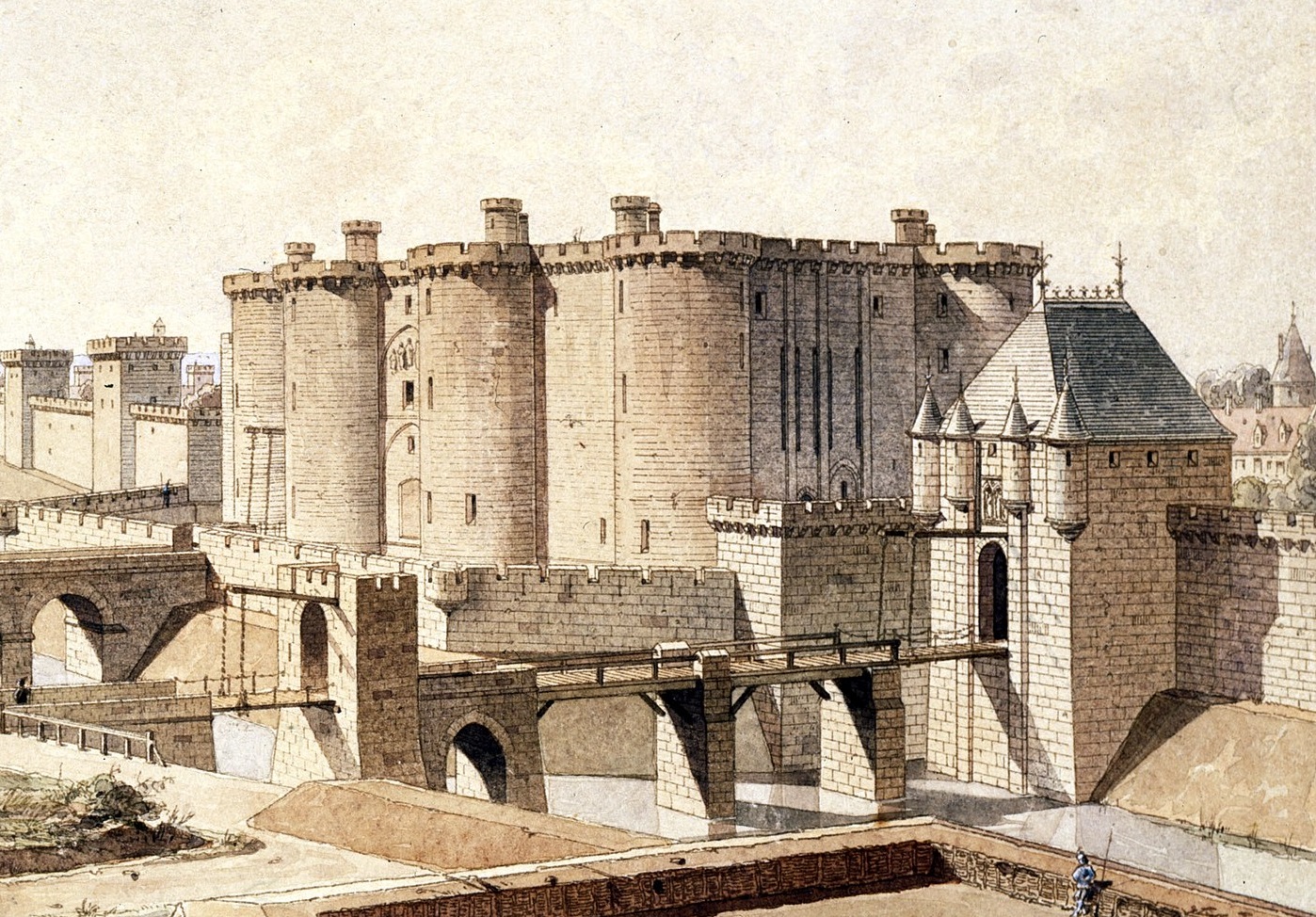

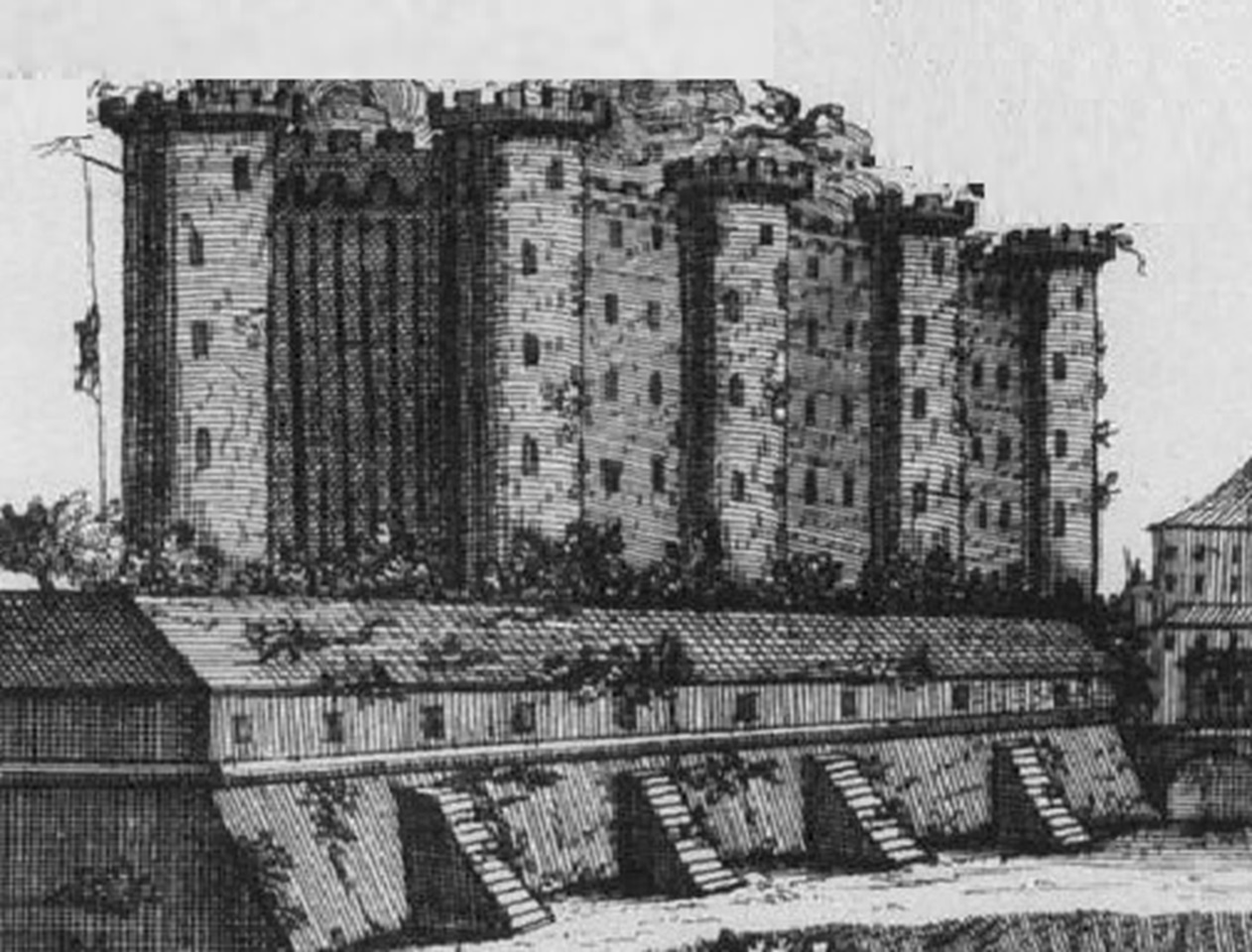

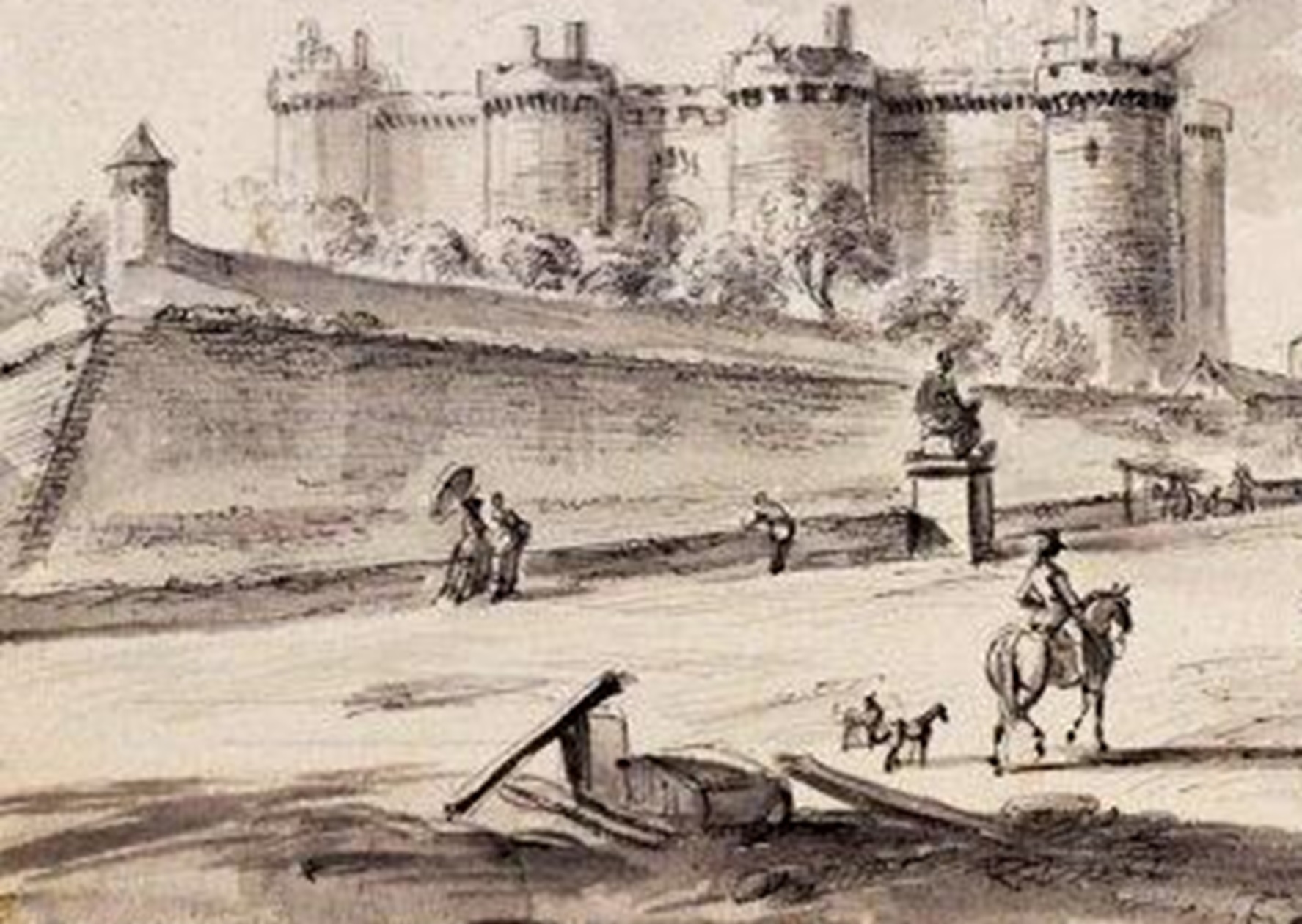

The Bastille fortress was built starting around 1370, to defend Paris from England during the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453). The Bastille consisted of eight irregularly built towers, with six cachots, or dungeons, built under the towers. It was described as one of the most powerful fortifications of the period, and the most important fortification in late medieval Paris.

Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer, Wikimedia Commons

Theodor Josef Hubert Hoffbauer, Wikimedia Commons

Continued Threats To Paris

During the 15th century, French kings continued to be threatened by outside forces. Because of its strategic position, the Bastille was vital to Paris' defenses. The fortress was occasionally used to hold prisoners—its first prisoner was Hugues Aubriot, the administrator who built the Bastille.

The First Prisoner Of The Bastille

Hugues Aubriot aided Paris' Jewish population, arresting Parisians who harassed them. Because of this and trumped-up charges, including heresy and extortion, Aubriot was sentenced to life imprisonment on bread and water. During rioting over excessive taxation, a mob released Aubriot and he fled the city.

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Picryl

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Picryl

The Bastille Becomes A State Prison

By 1417, the Bastille was converted into a state prison, while continuing to also be a royal residence. In 1420, Henry V of England captured Paris and the Bastille was seized. English troops occupied the Bastille for the next 16 years. The English expanded the use of the Bastille as a prison and in 1430, prisoners attempted to seize control of the fortress.

James William Edmund Doyle, Wikimedia Commons

James William Edmund Doyle, Wikimedia Commons

Louis XI And The Bastille As State Penitentiary

During the reign of Louis XI, the Bastille was again used as a state prison. However, the Bastille retained the other traditional functions of a royal castle, and was used to accommodate visiting dignitaries, with lavish parties hosted by kings Louis XI and Francis I.

Turning The Bastille Into A Military Complex

In the 16th century, under Charles IX, the Bastille became part of a major military center, surrounded by an armory and facilities to produce cannons and other weapons. In the 1550s, Henry II further expanded the Bastille's defences.

François Clouet, Wikimedia Commons

François Clouet, Wikimedia Commons

History's most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily.

Wars Between Protestant And Catholic Factions

Numerous wars between Protestant and Catholic factions, with support from foreign allies, centered around the Bastille during the second half of the 16th century. Religious and political tensions in Paris initially exploded on May 12, 1588, known as the Day of the Barricades.

Paul Lehugeur, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Lehugeur, Wikimedia Commons

Revolt Of Hard-Line Catholics

Hard-line Catholics revolted against the moderate Henry III. The king fled and the Bastille surrendered to the Duke of Guise, the leader of the Catholic League. Henry III had the duke and his brother murdered later that year. The duke's supporters used the Bastille as a base to mount a raid on the Parliament of Paris, arresting the president and other magistrates, and detaining them in the Bastille.

Musée Carnavalet, Wikimedia Commons

Musée Carnavalet, Wikimedia Commons

A Stronghold For The Catholic League

Henry IV attempted to retake Paris over a period of several years. The area around the Bastille formed the main stronghold for the Catholic League and their foreign allies, including Spanish and Flemish troops. Henry IV entered Paris in 1894, seizing the capital and the arsenal complex around the Bastille.

Bernard de Montfaucon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard de Montfaucon, Wikimedia Commons

Transformation Into A State Prison

The Bastille continued to be used as a prison and a royal fortress under both Henry IV and his son, Louis XIII. In 1602, conspirators among the senior French nobility came up with a Spanish-backed plot against Henry IV. Unfortunately for them, the plan was thwarted—and their leader was executed in the courtyard of the Bastille. Cardinal Richelieu, under Louis XIII, began the transformation of the Bastille into a more formal branch of the French state, further increasing its structured use as a state prison.

Anonymous, 1719, Wikimedia Commons

Anonymous, 1719, Wikimedia Commons

Another Insurrection

In 1648, an insurrection broke out in Paris, prompted by high taxes, inflated food prices, and disease. Various factions fought for several years to take control of the city. After the death of Louis XIII, his wife, Anne of Austria, ruled France as regent. Anne ordered the arrest of some of the leaders of the insurrection and violence once again broke out in Paris.

After Charles Beaubrun, Wikimedia Commons

After Charles Beaubrun, Wikimedia Commons

The Beginning Of The Reign Of Louis XIV

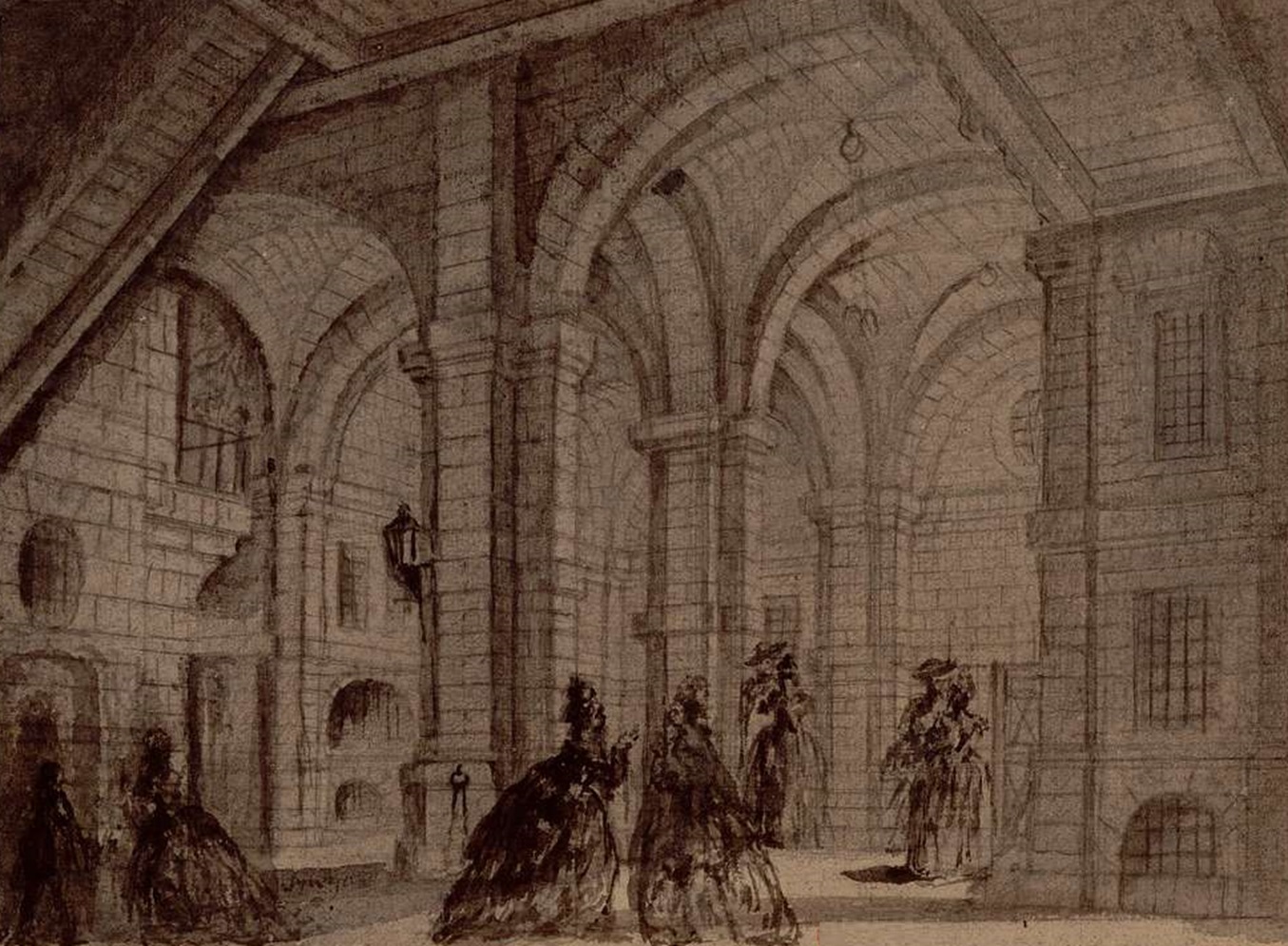

In the 17th century, Anne of Austria's son, Louis XIV, began his long reign. The area around the Bastille was transformed in his reign, as Paris grew beyond the boundaries originally protected by the Bastille. Louis XIV made extensive use of the Bastille as a prison, with 2,320 people being detained there during his reign.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Louis XIV And The Absolute Power Of The King

Louis used the Bastille to hold not just rebels or plotters but also those who had irritated him in some way, marking his reign as that of absolute monarch. Louis personally decided who should be imprisoned at the Bastille. Detention in the Bastille was typically ordered for an indefinite period and there was considerable secrecy over who had been detained and why.

Hyacinthe Rigaud, Wikimedia Commons

Hyacinthe Rigaud, Wikimedia Commons

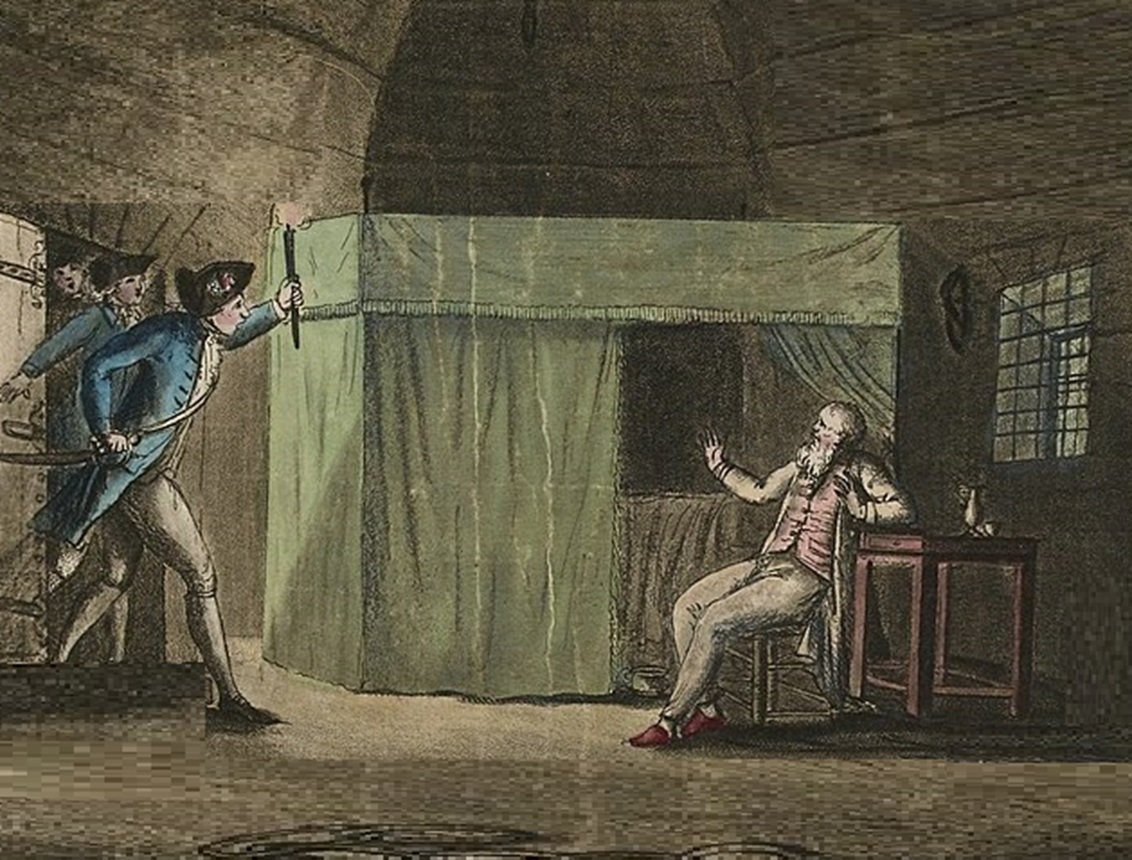

The Man In The Iron Mask

Perhaps the most famous prisoner during the reign of Louis XIV was the so-called Man in the Iron Mask. He was an unidentified prisoner of state and held for 34 years. When he perished at the Bastille on November 19, 1703, his death certificate bore the pseudonym "Marchioly".

Alphonse de Neuville, Wikimedia Commons

Alphonse de Neuville, Wikimedia Commons

A Prison For Common Criminals

The role of the Bastille as a prison changed considerably during the reigns of Louis XV and Louis XVI. A shift also took place in the role of the Bastille as a prison primarily for upper-class prisoners, toward a prison for holding socially undesirable individuals of all backgrounds. In particular, it was used to support law enforcement operations, especially those involving censorship.

Jacques Callot, Wikimedia Commons

Jacques Callot, Wikimedia Commons

A Way To Avoid Public Scandals

Many prisoners continued to come from the upper classes, particularly in those cases deemed "disorders of the family". These were members of the aristocracy who had disgraced the family reputation or "manifested mental derangement," and the families could apply for individuals to be detained in order to avoid a public scandal.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Wikimedia Commons

The Banning Of Books

During the 18th century, the Bastille was used by law enforcement to suppress the trade in "illegal and seditious books". In the 1750s, 40% of those sent to the Bastille were arrested for their role in manufacturing or dealing in banned material.

Houel, Jean, Wikimedia Commons

Houel, Jean, Wikimedia Commons

Being Imprisoned For Publishing Books

Many of those writers detained under Louis XVI were imprisoned for their role in producing illicit writing. Writers were formally detained not for their more obviously political works, but for libelous remarks or for personal insults against leading members of Parisian society.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

A Symbol Of Despotism

During the 18th century, the Bastille was extensively criticized by French writers as a symbol of despotism, resulting in some reforms. The first major criticism was by Constantin de Renneville, who had been imprisoned in the Bastille for 11 years and published his accounts of the experience in 1715, in his book L'Inquisition françois.

Constantin de Renneville, Wikimedia Commons

Constantin de Renneville, Wikimedia Commons

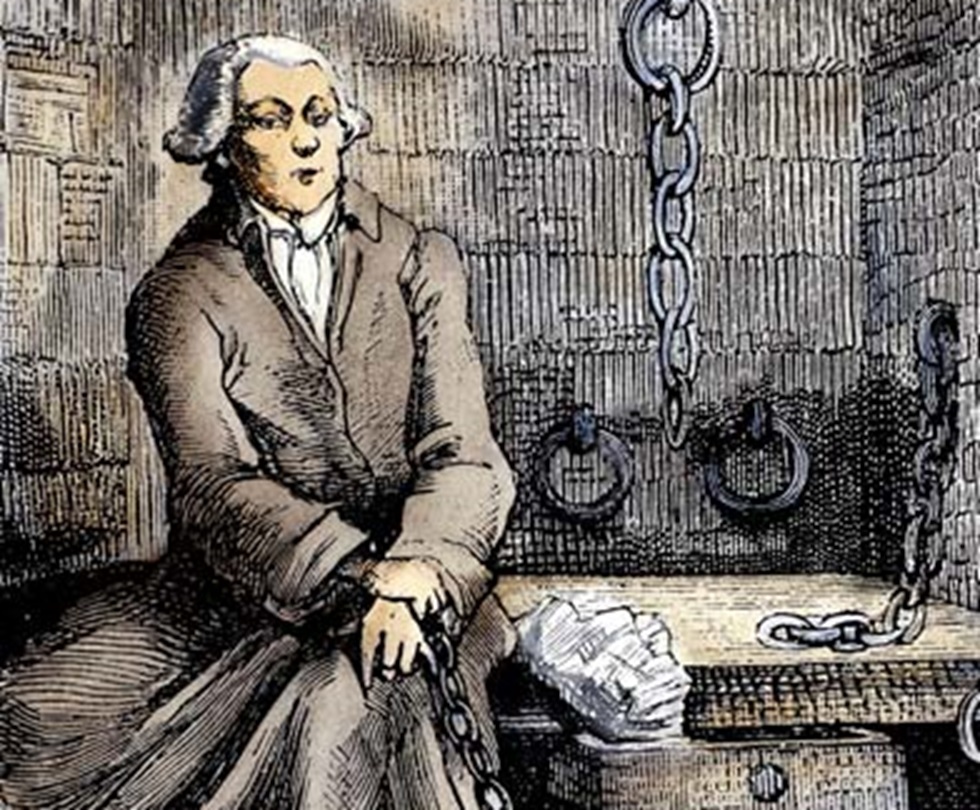

Being Left To Rot

Renneville presented a dramatic account of his detention, stating that despite being innocent, he had been abused and left to rot in one of the Bastille's dungeons, chained next to a lifeless body. Abbot Jean de Bucquoy, who had escaped from the Bastille 10 years prior, called the Bastille the "hell of the living".

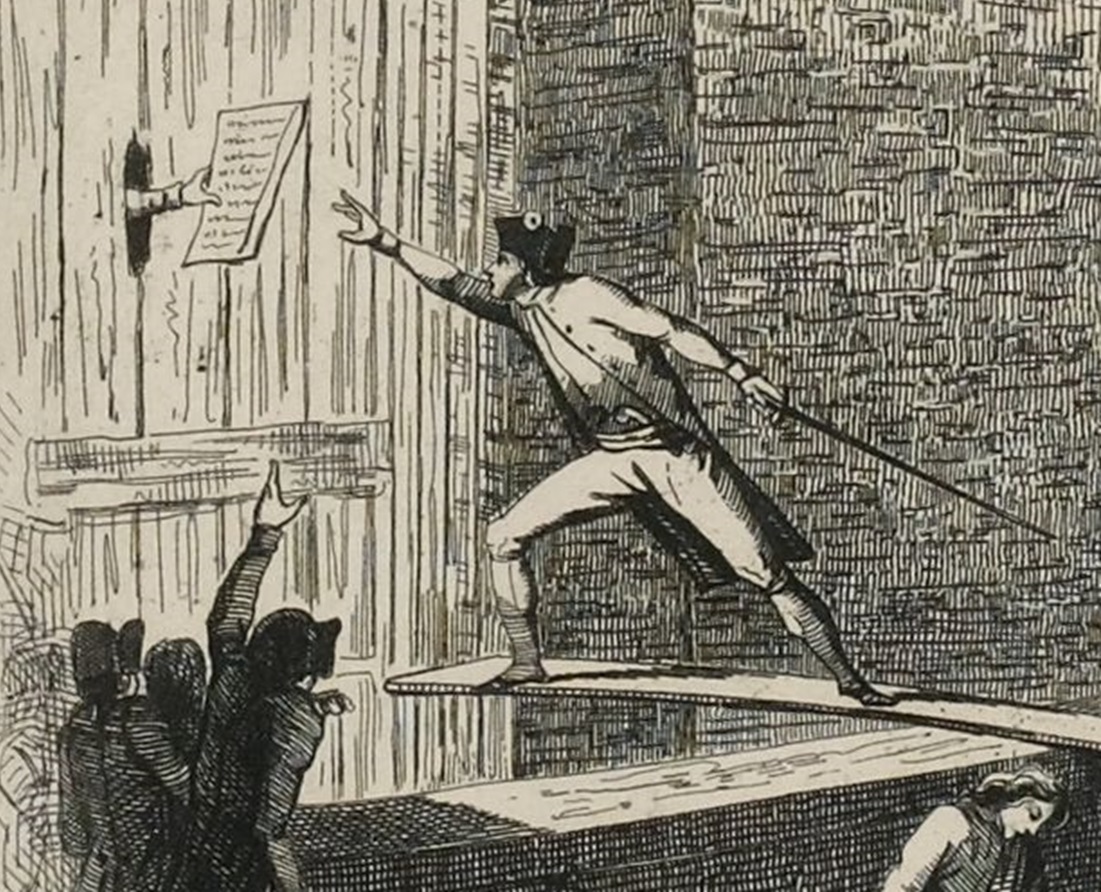

Prison Reform

Prison reform became a popular topic for French writers. One writer encouraged Louis XVI to destroy the Bastille, publishing an engraving depicting the King announcing to the prisoners, "May you be free and live!"

Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Wikimedia Commons

Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Wikimedia Commons

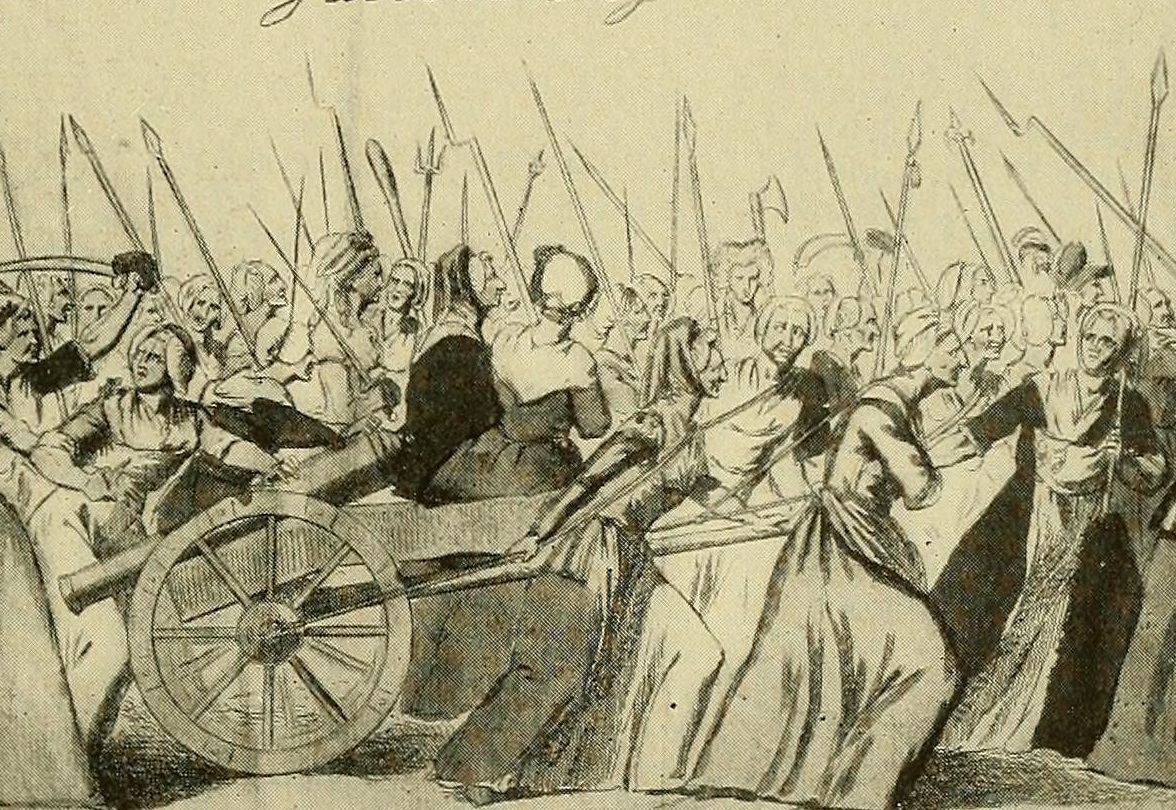

The Revolutionary Spirit

By July 1789, revolutionary sentiment was rising in Paris. Members of the mercantile class called for the King to grant a written constitution. Violence between royalist forces and local crowds broke out at Vendôme on July 12. Revolutionary crowds armed themselves by looting royal stores, gunsmiths, and armorers' shops for weapons and gunpowder.

Internet Archive Book Images , Flickr

Internet Archive Book Images , Flickr

The Marquis De Sade

Tensions surrounding the Bastille had been rising for several weeks. Only seven prisoners remained in the fortress. The Marquis de Sade, perhaps the Bastille's most infamous prisoner at that time, had been transferred to the asylum. Sade had claimed that the authorities planned to slaughter the prisoners in the castle.

The Granger Collection, Wikimedia Commons

The Granger Collection, Wikimedia Commons

Securing The Bastille

The Bastille was fortified and its gates locked. The fortress, already unpopular with the revolutionary crowds, was now the only remaining royalist stronghold in central Paris. It was also protecting a recently arrived stock of 250 barrels of valuable gunpowder. The Bastille had only two days' supply of food and no source of water, making a long siege impossible to defend against.

Hollande, École, Wikimedia Commons

Hollande, École, Wikimedia Commons

The Revolutionary Forces Arrive

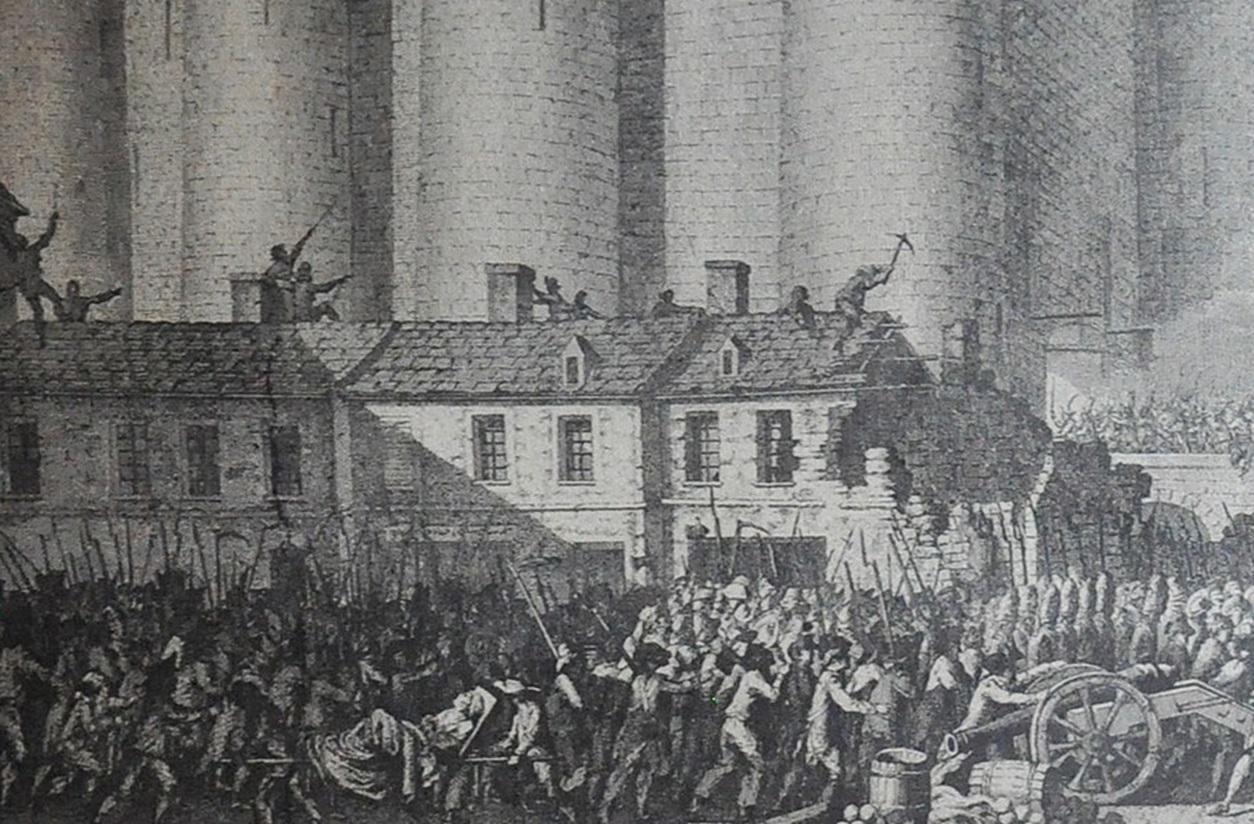

On July 14, around 900 people arrived at the Bastille. The crowd had gathered to commandeer the gunpowder stocks known to be held in the building . The revolutionary forces wanted both the guns and the gunpowder in the Bastille to be handed over.

Gauthier or Gouthier, Wikimedia Commons

Gauthier or Gouthier, Wikimedia Commons

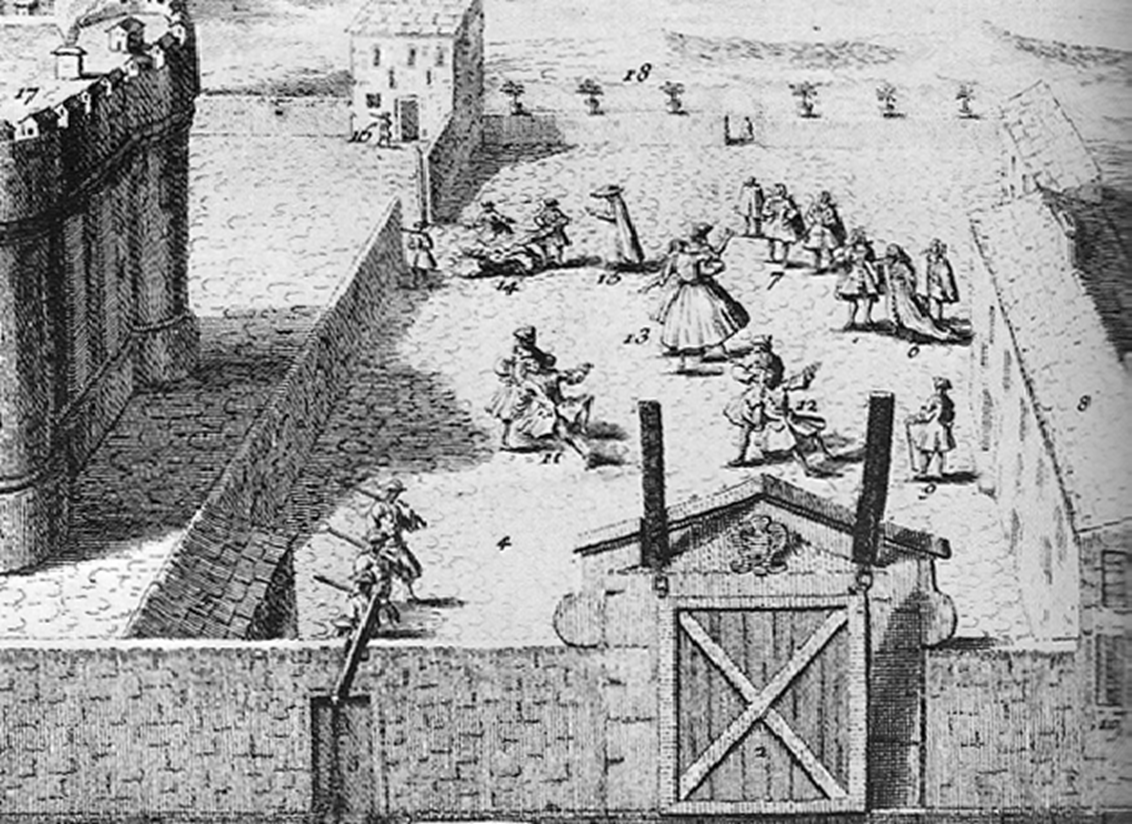

The King's Forces Begin Firing

That afternoon, chaos broke out as the crowd stormed the outer courtyard of the Bastille, pushing toward the main gate. Confused firing broke out in the confined space and chaotic fighting began in between the King's forces and the revolutionary crowd.

Clément Denis, Simon Joseph Alexandre, Wikimedia Commons

Clément Denis, Simon Joseph Alexandre, Wikimedia Commons

The Chaos Continues

At around 3:30 pm, mutinous royal forces arrived to reinforce the crowd, bringing with them trained infantry officers and several cannons. As the skirmish continued, 83 members of the crowd were slain and another 15 were mortally wounded.

The Storming Of The Bastille

Attempting to negotiate a surrender, the commander of the Bastille threatened to blow up the fortress. In the midst of this, the Bastille's drawbridge suddenly came down and the revolutionary crowd stormed in. The commander was dragged outside into the streets and killed by the crowd. The valuable powder and guns were seized.

A Symbol For The Revolutionary Movement

Within hours of its capture, the Bastille began to be used as a symbol to give legitimacy to the revolutionary movement in France. Although the crowd had gone to the Bastille searching for gunpowder, the captured prison became a representation of everything the revolutionary forces were fighting against.

Unknown Author , Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author , Wikimedia Commons

Machines Of Doom

The more despotic the Bastille was portrayed by the pro-revolutionary press, the more necessary and justified the actions of the Revolution became. The Bastille was described by the revolutionary press as a "place of slavery and horror", containing "machines of death", "grim underground dungeons," and "disgusting caves" where prisoners were left to rot for up to 50 years.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Destruction Of The Bastille

The revolutionary leaders decided to symbolically start the destruction of the Bastille, after which, a panel of five experts was appointed to manage the demolition of the castle. By November, most of the fortress had been destroyed.

Claude Cholat, Wikimedia Commons

Claude Cholat, Wikimedia Commons

The Ruins Of The Bastille

The ruins of the Bastille rapidly became iconic across France. An altar was set up on the site in February 1790, formed out of iron chains and restraints from the prison. Old bones were discovered during the destruction and were thought to be the skeletons of former prisoners.

Philippe Alès, Wikimedia Commons

Philippe Alès, Wikimedia Commons

Relics Of Freedom

An industry of memorabilia surrounding the fall of the Bastille began to flourish. Called "relics of freedom", they included a wide range of items. Models of the Bastille, carved from the fortress's stones, were used as gifts—and a way of spreading the revolutionary message—in the French provinces. In 1793, a large revolutionary fountain was built on the former site of the fortress, becoming known as the Place de la Bastille.

Pierre-Yves Beaudouin, Wikimedia Commons

Pierre-Yves Beaudouin, Wikimedia Commons

Napoleon Bonaparte

The Bastille remained a powerful and evocative symbol for French Republicans throughout the 19th century. In 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the French First Republic that emerged from the Revolution and attempted to marginalize the Bastille as a symbol. Napoleon was unhappy with the revolutionary connotations of the Place de la Bastille, and initially considered building his Arc de Triomphe on the site instead.

The Remains Of The Ruins Of The Bastille

This proved to be unpopular and he instead planned the construction of a huge bronze statue of an imperial elephant. The project was delayed and all that was built was a large plaster version of the bronze statue. It stood on the former site of the Bastille between 1814 and 1846, when the decaying structure was finally removed.

Jean-Baptiste Lallemand, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Baptiste Lallemand, Wikimedia Commons

An Underground Symbol

After the restoration of the French monarchy in 1815, the Bastille became an underground symbol for Republicans. The July Revolution in 1830 used images such as the Bastille to legitimize their new regime and in 1833, the former site of the Bastille was used to build the July Column to commemorate the revolution. The short-lived Second Republic was symbolically declared in 1848 on the former revolutionary site.

Photographed by Commission du Vieux Paris, Wikimedia Commons

Photographed by Commission du Vieux Paris, Wikimedia Commons

The 20th Century

The Bastille lost its prominence as a symbol by the 20th century. Nonetheless, the Place de la Bastille continued to be the traditional location for left wing rallies, particularly in the 1930s. The symbol of the Bastille was widely evoked by the French Resistance during WWII and until the 1950s, Bastille Day remained the single most significant French national holiday—and it’s still one of the most popular celebrations today.

Mbzt, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mbzt, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons